Leopard skin

The leopard and the leopard skin played a major role in their countries of origin in ancient times. As a garment of modern times, the leopard fur was particularly popular around the middle of the 20th century, along with the fur of other conspicuously patterned cat species.

The leopard , also known as panther, formerly also called "leopard lion", is the same animal, the second term is common for the black panther , a total blackness ( melanism ).

The leopard is one of the endangered species. It has been completely protected since March 3, 1973 and is listed in Appendix I of the Washington Convention on the Protection of Species . From some African countries it can be imported as a hunting trophy, but trade is prohibited.

history

antiquity

In the excavations of Çatalhöyük in today's Turkey, one of the oldest settlements known to us - it existed until around 6200 BC. BC - there are depictions of the leopard, which apparently had an essential meaning there. It is believed that his fur was used as men's clothing, as can be seen on various wall paintings of dancers interpreted as hunters. One interpretation assumes that the dances are initiation rites.

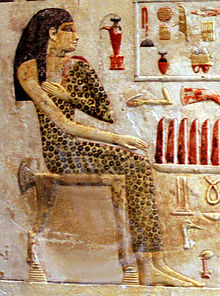

On ancient oriental works of art, leopard skin can be seen as the costume of particularly distinguished people. Certain classes of priests in ancient Egypt wore full leopard fur as their official costume. Egyptian princesses adorned themselves with the spotted fur as a pompous costume.

In the second burial mound ( Kurgan ) of Pazyryk in the Altai from the 4th century BC, in addition to other furs, there was a pair of riding boots with leopard skin shafts, which a Scythian princess was placed in the grave of a Scythian princess when she was her slain husband in the Death had to follow. The leather-colored and red foot and the upper edge are studded with leather applications and embroidered, the sole is adorned with multicolored ornaments and pearls.

Leopard hunting, with a lance or sword, was a royal sport , an obligation of the rulers as the "fathers" of their people . As tribute payments, leopards came to Egypt from the Nubians as live animals and as furs. Around 1500 BC They must have already been exported to Greece. Only distinguished Egyptians are depicted with leopard coats in the Old Kingdom of Egypt (around 2700 to 2200 BC). In the representations, however, the leopard skin predominates as an attribute of goddesses in representational and cult scenes. In Egypt the leopard is the animal of the goddess Mafdet and the goddess Seschat , in Syria the goddess of war and love Anat . The much venerated mother goddess occasionally wears a leopard collar or a leopard skin tied around her body. Several times in the Old and Middle Kingdom (2137 to 1781 BC) the fur was reproduced as an expanded sarcophagus cover.

In the New Kingdom (1550 to 1070 BC) the leopard was no longer reserved for kings and priests. On a mural from the tomb of Rechmire (14th century BC), two of the Cretan tribute- bringers are wearing elegant apron skirts made of leopard skin . In the victory scenes of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun , Libyans are also dressed in leopard skin aprons . On the other hand, the fur aprons or skirts of the African peoples, which are not uncommon in images of the New Kingdom, appear to be made of leopard skin only in exceptional cases. However, Nubian princes are sometimes depicted with elaborately crafted clothes that are trimmed with stripes of leopard skin (12th century BC, the time of Ramses X ).

In inlay work in the Ištar temple of Mari (around 2500 BC) soldiers and priests can be seen wearing leopard skins over their other clothing. In the grave of Chnummose (TT30), "scribe of the treasury of the house of Amun" in the 20th dynasty, the priest also wears the panther skin over his cloth costume. Tutankhamun (reign approximately from 1332 to 1323 BC) wears a leopard skin vest, especially in battle and hunting depictions.

Leopard skins were not only used for clothing. In the grave of Kenamun ( TT93 ) a large shield is brought that appears to be covered with the skin. In one of the most famous musician scenes, a wall painting from the grave of a man named "Nacht", which means "the strong", in the Theban city of the dead , the sound box of a harp is covered with leopard skin (reign of Thutmose IV, 1425 to 1401 BC. ). In the New Kingdom, a special gift from Nubia to the Pharaoh seems to have been ceremonial tables adorned with gold and leopard skins, for example in the tomb of Huy , the viceroy of Kush under Tutankhamun. In the antechamber of Tutankhamun's grave ( KV62 ), both a replica of a leopard skin and a real one were found. The real, very small leopard skin lay on a wooden chest, it was only badly preserved. There was also an artificial, gilded leopard head that served as a holder of the fur.

Eje , dressed in a leopard skin, performs the mouth opening ritual on Tutankhamun. Representation from the burial chamber.

Depiction of panther skin from the tomb of Huy

The standard-bearers of the Roman legions , the rallying point of the attacking armed forces, traditionally wore leopard skins over their clothing, as well as other types of fur such as lion skin , bears or wild boar . A maximum price edict (tax ordinance) by the emperor Diocletian from the year 301 AD documents the trade in leopard skins in the Roman Empire . The maximum price for leopard skins was: unprocessed 1,000 denars, processed 1,250 denars, the most expensive were seal skins with 1,250 or 1,500 denars. In comparison, a marten skin cost 10 and 15 deniers.

Modern times

Around 1900 the fur trade still used the generic term leopard for all big cats with dark spots. Until the First World War , real leopard skins, like those of other big cats, were mainly processed into rugs (naturalized, with head and paws), saddlecloths and the like. The largest deliveries of leopard skin came from China.

While in ancient Egypt it was mostly the priest of the dead who wore the leopard skin, in Central Africa it is the circumcision priest. Among the Nuba , the priest-king wears the cat's skin at the circumcision celebrations. Among the Luba , the circumcision priests are called "leopard" (or lion). The existing Ryangombe Association in Urundi unites people who put on leopard skins to transform themselves into "Ryangombe" (leopards). In the Egbo of Nigeria , the members of the top secret level wear a leopard mask . "The dignitaries of this federation (the Mken-Bund der Bamileke ) wear panther skins during the dances, and the cult idol of this federation stands on a panther skin ..." The leopard federations are widespread up to Sierra Leone , mostly the belief prevails by wearing the Felles to become a big cat himself. At the same time, lion and leopard were almost exclusively the symbolic figures of African kings, some of whom wore fur or at least fur strips or fur hats from it. The fur is widespread as a throne cushion, for example among the Akan and the Schilluk . In some places the king was even seen as the embodiment of the big cat - the Uganda rulers never had their nails cut because they were leopard claws. The royal umbrella of the Ashanti is decorated with a stuffed leopard. In many places, leopard skins adorn the king's drums and the musicians wear cat skins. The Schilluk rulers were buried in leopard skins, as were the Bantu chiefs of Southeast Africa.

In some countries, leopard skins were used in the army, as saddlecloths , saddlecloths for special occasions, as protective leather for drummers or as a decorative element of clothing. In some places, leopard fur was part of the equipment of African warriors and as the decoration of the huts of the chiefs there. The Impi , the regiments of the two tribal kings Mzilikazi and Lobengula of the Matabele Kingdom as well as others received leopard skins as a uniform. The local tribes (" Kaffirs ") also valued blankets made of leopard skin, so-called " bodies " , as clothing . The beautiful blankets tanned by the women were already too expensive in the country to be considered as export items. Royal bodies of the Zulu kings Shaka , Dingane , Mpande and Cetshwayo were made of leopard skin as a status of their royal power, as elsewhere to this day the ermine skin . Even now in South Africa Zulu rulers and believers of the Nazareth Baptist Church present themselves with leopard skins. With the Nuer from South Sudan and Western Ethiopia there is no institution or individual who fulfills the task of the legislature (legislative power), executive (executive power) or judiciary (judiciary). In worse cases, a so-called " leopard skin chief " is called in to settle the dispute.

So-called ancestral stools are of considerable importance in the Akan culture (West Africa). The most famous of the stools called “Stool” by the Akans is a golden Ashanti chair named Sikadwa Kofi. The Sikadwa Kofi is so sacred that no one is allowed to sit on it. The golden chair is guarded with great security and is only presented on rare and very high occasions. According to the belief of the traditional Ashanti, it must never touch the ground. Therefore it is usually placed on a precious animal skin made of elephant skin or leopard skin.

In China and Korea , the pelts were a popular armchair decoration in the houses of the mandarins , and the paws were also very popular.

During their stays in the Indian colony, English officers hunted, including the leopard hunt. The trophies should also be shown if possible, at least that is assumed to be a major reason for the introduction of leopard skin into the British army. According to the War Office Library London, there were two types of use there:

- Some cavalry regiments had officer saddlecloths made of leopard skin, several infantry regiments had leopard skin protective leather for the drummers. For the cavalry, the leopard skins for officers for the light cavalry were first mentioned in the Dress Regulation of 1834, but only for some regiments. The others used plain black lambskins . In the course of time, more and more cavalry regiments took over leopard skin for saddle equipment, until around 1890 all hussar regiments - except for the 14th - used leopard skin. After the First World War (1918), the 14 Hussars, now united with other hussar regiments that together formed the 14 to 20 Hussars, remained the only hussar regiment that did not have leopard skin saddles. After the Second World War (1945) all hussar regiments were motorized and part of the Royal Armored Corps, which meant that the fur was no longer used.

Austrian nobles, who formed the royal bodyguard, wore cloaks that were lined and trimmed with small, fine leopard skins. For the Austro-Hungarian Army , the following regulations applied to the use of leopard saddlecloths:

- As part of the parade saddlecloths for generals of the Hungarian cavalry (with hussar uniform). In the adjustment regulations for officers of the KK Army from 1837 from 1855 it says: "... Covered with scarlet cloth with tiger skin ..." A drawing in the Army History Museum in Vienna , however, indicates more leopard skin than tiger skin. For saddlecloths of the Hungarian Life Guard: “... made of green cloth. Saddle skin made of panther skin (length approx. 60 cm, width approx. 75 cm) ... “ Otherwise lambskin was prescribed for the saddlecloths in the KK monarchy.

For officers of the 18th century, a tiger skin (panther skin) covering the back was considered an award. A metal clasp held the fur together over the chest. On special days and at gala events it was worn instead of fur, for example by the Prussian Zietenhusars . The Hungarian magnates in gala dress and the Hungarian bodyguard had leopard skins over their shoulders. The Royal Hungarian Life Guard maintained this throughout the century, until the fall of the empire. The Polish Uszarzy, the country's elegant elite troop at the time of Johann Sobieski (* 1629, † 1696) , also wore a tiger or panther skin over their armor . The French dragoons, which were one of the oldest branches of arms in their country, had fur-trimmed pointed hats from the end of the 17th to the middle of the 18th century (also in Spain). After the helmet had been introduced there, the yellow helmet of the Guard Dragon regiment was adorned with a small trim made of panther skin.

In the early years of fashion decorative, large sleeve were tiger, panther and leopard skins used for this purpose. At the beginning of the 20th century, thanks to improved fur finishing , the pelts were increasingly processed into sporty jackets and coats in the context of civilian fashion. This was especially true for short-haired, effectively drawn, light-leather African leopards, such as those that came from Somaliland and the neighboring areas (Erithrea, Abyssinia). The first larger offers with matching leopard skins appeared in the spring of 1911, "after some pretty models had been shown by London companies and bought in Paris". America followed as the next supplier of clothing made from big cat skins. In addition to women's coats, automobile jackets were also made from leopard skin around 1925, when cars were not yet heated.

Around 1950 the seats of a car destined for the Negus of Abyssinia were instead covered with leopard skin, which could be viewed in a Berlin car dealership. The Negus distinguished his guard with a leopard poncho , the Lemt . In 1937 a specialist fur newspaper reported on Abyssinia as a trading center for fur skins: the leopard was at the top of the ranking . The best skins come from Somaliland. Every flawless hide of this provenance achieved 60 Maria Theresa thalers in normal times on the Abyssinian market . Less valued leopard skins come from the areas of Gimma , Kassa , Arussiland and Sidamo . The collection point and market for leopard skins was Bali . All other leopard skins, as far as they came on the market, were delivered to Addis Ababa or Diredaua . The prices varied between 20 and 40 thalers, depending on the preservation and origin. The market was supplied almost exclusively by Indian and Abyssinian buyers who traveled to the hunting areas. During the times of the Negus Empire, an agent from American trading houses came to the Ethiopian collection points once a year and bought what was available on the market to export via Djibouti . That was 2000 to 3000 Somalileopards and 5000 to 6000 leopard skins of other origins each year.

Leopard was often used as a trimming of the then fashionable black, velvety seal fur and its cheaper imitations of sheared muskrat fur , the Hudson “seal”. Other varieties were still largely processed into templates and hunting trophies.

Anna Municchi felt that 1911 was the debut of modern leopard fur, with a photo published in Vogue of a magnificent, floor-length leopard fur coat, trimmed with skunks on the neck and sleeves . In 1933 the actress Lilian Harvey bought a leopard coat from Joe Strassner in Berlin, along with a sable coat . In 1966, the American folk and rock musician Bob Dylan published his song Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat , in which he made fun of the women's pillbox headgear, which was popular again in the 1960s, particularly through Jacqueline Kennedy .

In the 1950s, after the USA , the fashion of the spotted wild cat skins also experienced an absolute peak in Europe (especially ocelot ), the resulting sharp increase in purchase price led to a general threat to the animal species. In 1973 the leopard was therefore finally placed under protection. For almost all types of wild cat fur, there has also been a trade ban, or at least significant trade restrictions, since around this time.

The small amount of leftover leopard fur during fur processing was not enough to make it an essential article of fur processing . The extremities, the leopard paws, for attractive fur lining or as embellishments used. Occasionally, the suitable types of leopard paw capes and a few coats were made from the appropriate types (for example from the Mombasa (Kenya) and Asmara (Eritrea) types). In the first quarter of the 20th century, car driver and sled coats were made from the tails in small numbers. Pieces of leopard were used very well in mosaic work to represent the rock areas .

Inexpensive types of fur, such as lamb, rabbit fur and calf , were often "refined" with a leopard pattern. 1926 Leopard cost 70 marks average, however, the much smaller leopard colored Zickelfell contrast 3 Mark.

The leopard pattern became particularly popular as a textile design in the 18th century. Even after clothing was no longer made from leopard skin, leopard remained the most common big cat design in women's fashion.

Margaretha Frisching with a leopard-lined plaid (1749)

Chief Sarili or Kreli der Gcaleka ( belonging to the Xhosa ) with leopard skin (1890)

Tibetan Gurkha soldier with leopard cloak (1938)

Leopard skin, shoulder cape (Akaulat) of the Karamojong (before 1967)

hide

Natalie Wood in a leopard coat, for the film Penelope (1966)

Leopard coat ( Revillon Frères , ca.1983 , Metropolitan Museum of Art)

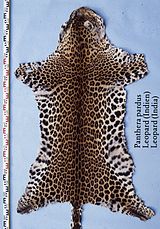

Leopard skins are 95 to 150 centimeters long, the tail 60 to 95 centimeters.

- Coloring - drawing

Basic color :

- Ocher-yellow to yellow-brown to olive-pale yellow-gray on the back, lighter on the sides, white on the belly (leopards in open areas such as savannas and steppes are usually brightly colored, rich to light ocher; such dry highlands as Persia and cooler areas such as the Amur are very light, cream to pale gray-yellow, sometimes almost white). In addition to this "normal coloration", the black mutation form occurs sporadically in the entire distribution area (black panther). Its basic color is deep black-brown to black, the spots shimmering black when the light falls. In a litter of the female leopard there can be "normal" spotted and black cubs at the same time. There are animals in which the markings can still be seen quite well, in other melanos the basic color is deep black. Without geographical restrictions, other mutations sometimes occur, such as nigrism (the basic pattern can be recognized despite the black color ), abundism (more pattern than normal) and flavism (the basic color is strongly lightened). Black flies can occur in the entire distribution area, they are more common in the Malay region, Java and Ethiopia. Light color deviations are also known, even at least one white copy.

Drawing :

- Both varieties are spotted black over the whole body, in the normally colored leopards the speckles clearly stand out from the basic color, in the blacks it only shimmers through weakly. The mostly smooth and shiny fur often has very different coat patterns depending on the subspecies, but individual differences also occur within one area. The fur almost always shows blackish ring spots, which are arranged in rows, especially in the longitudinal direction of the back. The drawing is distributed almost symmetrically over the body. The basic color only emerges like a net between the spots.

- On the chest and lower neck, instead of side-by-side rosettes, “strawberry spots” are often found, which are arranged in one direction and act like collars. At the top of the long tail, the ring spots continue along the center line. The middle of the abdomen and the upper inside of the legs are also free of ring spots and colored white, yellowish-white or turning gray. Farther towards the paws, there are full stains that get smaller and smaller towards the bottom. There are full spots of various sizes on the head, neck, mostly also on the neck, and spotless areas on the extremities. The full spots on the dewlap are large and farther apart than on the back, making them appear much lighter. The sides, shoulders, thighs and often the back have ring spots that vary in size depending on the occurrence, from about the size of a walnut to seven centimeters. The ring spots consist of ring-like (small) figures of various shapes, including sections of circles, crescent-like spots. The number of these figures forming a rosette is different. Usually there are five to seven, at most eight, rarely two. In individual animals in both Africa and Asia, as is typical for the jaguar, black spots (fill spots) can appear, especially in the larger rosettes that are located towards the back.

- At the base of the tail, the ring spots continue in rings that are open at the bottom and are less and less pronounced towards the end. They go over to the rear in full spots that predominate up to the tip of the tail. Occasionally the tail is completely spotted. The underside of the tail is very light to white towards the end. The tip of the tail is pure white in normal colored animals.

Forest leopards are generally more intensely colored than leopards in open landscapes. The hairiness of the leopards in hot areas is shorter and flatter, in the north and in the mountains longer and more hairy (smoker). The most distinctive markings can usually be found on more short-haired and not too silky skins. These also have the bright basic colors and the shine that is just as necessary, so that the desired contrast is achieved, which is easily blurred with long hair - quality features that were once created for the fur trade. The Somali leopards from Central Africa were considered to be the most valuable ; those from Kenya, Eritrea and Tanganyika are almost equal.

Pelts from mountain occurrences and from the north have significantly denser and longer hair, and winter hair is longer and denser than summer hair. In the Amur leopard, the hair on the back is 20 to 25 millimeters long, in the winter fur it is a good double the length of 50 millimeters. The hair on the abdomen is longer than that on the back. As an animal in tropical and subtropical areas, the jaguar does not have a short-term seasonal coat change , it extends over the whole year.

When the fur types are divided into the hair fineness classes silky, fine, medium-fine, coarse and hard, the leopard hair is classified as hard. The durability coefficient for leopard skin is given as 50 to 60 percent.

Distinguishing features leopard fur - jaguar fur

The leopard skin is smaller and narrower than the similar jaguar skin, but its roughly body-length tail is significantly longer. The leopard has finer markings; the ring spots are smaller than in the jaguar. With a few exceptions, the rosettes have no points in the middle (fill spots). The figures in the leopard are smaller, closer together and more evenly distributed. The basic color is often less reddish, the back center line ( grunt ) is often much darker. The leopard's legs are longer and less strong, and the head is slimmer.

Sometimes the leopard skins are difficult to distinguish from the jaguar (aberrant / deviating patterns). Because of the low yield of fur, the jaguar was often traded as a leopard, so that the range of leopard skins often included jaguars.

Differentiation according to tradition

The leopard is the most widespread of all big cats. It extended over the whole of Africa (except the Sahara), as well as the Middle East and Asia Minor, Afghanistan, Russian Turkestan, Iran, Middle East and West India, Ceylon, Java, China, Korea, Manchuria and the Amur-Ussuri region. It has been eradicated in North Africa and the Cape, and it has also declined sharply in the other areas of distribution.

The following distinctions are based essentially on the appearance of the fur, not necessarily on the current zoological classification, which takes into account significantly different characteristics. Towards the end of the 1990s it was recognized that color variations in the fur were insufficient to adequately identify subspecies.

- Asia

- The coat of the Chinese leopard is more yellowish with slightly smaller spots. The fur is somewhat reminiscent of the Indian / Chinese origin from the left bank of the Ganges to southern China. The tail is bushier and the color is lighter, strong yellow, ocher yellow to reddish. The spots are large and with thick margins. The Latin name "japonensis" for this subspecies incorrectly suggests the presence of leopards in Japan. The name was given in 1862 by the zoologist Gray after a furrier's skin, which, however, probably came from China to Japan. Skins on the market in Canton are said to have a stronger yellow and larger spots than Indian varieties. Hangkau (Hànkǒu, today in Wuhan ): Small, densely hairy. North Szetschwan : Very large, impressively drawn.

- North China, Mongolia . Small skins with long, bushy tails. The hair is long, thick and smoky ; the undercoat soft; longer and softer on the stomach and neck, but not as close as on the rest of the body. The color is light, yellowish, lighter than those from India and southern China. The belly is whitish. 6 to 8 longitudinal rows of black, almost closed rings, interspersed with small, irregular full spots. Underside widely spotted. Tail with 10 to 12 full rings.

- Rear Indian leopard , Front India from the Himalayas to Cape Komorin , east to around Bhagalapore and the right bank of the Ganges. The ocher-yellow fur is more reddish in color, rarely brownish or gray-yellow. The thick-edged rosettes are somewhat smaller; on the back there is usually an almost uninterrupted row of elongated black spots along the midline, ring spots and rosettes on the sides, as well as on the thighs and shoulders. The courtyards of the spots are often bright orange-yellow. The head, partly also the neck and legs, are covered with numerous close-packed black spots, on the belly larger, further apart black spots.

- Left bank of the Ganges through Assam, Burma, Cambodia and the Malay Peninsula through the whole of rear India, in the north to the mountains of South Sikkims and Yunnans to the southernmost provinces of China ( Guandong , Guangxi , Fujian ) . Formerly common in Futsinghsien ( Fuqing in North Fujian ). The fur is quite small and short-legged. The back hair is about 1.5 to 2 inches long. Color: bright ocher to almost rusty red, rarely brownish. Spots large and with thick margins. The halos of the spots are usually much darker than the color between the rosettes.

- The coat of the Indian leopard is similar in color but varies in color and spot.

- The Java leopard , Java and Kangean Islands ( Jawa Timur Province ), has very small, closely spaced spots. The hair is short and smooth; the color dark and strong (about reddish ocher). Black spots are particularly common.

- The fur of the Sri Lankan leopard (formerly also Ceylon leopard ) is a little darker, more bright yellow-red: the rosettes are small and close together. The hair is longer and softer. The fur reaches a body length of about 110 to 150 centimeters.

- The Nepal leopard fur, Sikkim and Nepal, is lighter and mostly with large spots; the color somewhat paler, less bright. The fur is more long-haired and thicker than that of the leopards of the Indian lowlands.

- The cashmere leopard is darker in color than the Indian leopard, more olive; Rosettes small, with thick margins (Franke / Kroll: with large spots ).

- The Balochistani leopard fur from Sindh , Pakistan. Yellowish, related to the Persian leopard, but stronger in color, therefore and also because of the larger, thin-walled spots similar to the leopard of Asia Minor.

- The fur of the Middle Persian leopard found in Central Persia is small, light and short-haired.

- The fur of the North Persian leopard , which is a mountain dweller, is particularly long-haired and slightly larger than the aforementioned species. It is related to the Asian Minor, but much lighter, without reddish nuances. The rosettes are smaller. Similar in color to the snow leopard , also due to its strong winter fur, but much smaller spots. North Persian leopards ( Kopet-Dag , Ala Tau , Maschhad area ) are a little more yellowish, similar to those of Asia Minor. The leopards in the north of Iran are said to be mostly large, pale colored animals, while in the south rather dark colored, somewhat smaller specimens are said to occur. However, recent studies have not found any noticeable differences in the fur pattern between North Persian and South Persian leopards.

- Amur leopards are quite small. They differ from other subspecies by their thick fur, which is strongly and uniformly drawn. Leopards from the Amur river basin, the mountains of northeast China and the Korean Peninsula have pale cream-colored coats, especially in winter. The rosettes on the flanks are 5 × 5 centimeters in size, up to 2.5 centimeters apart and are made up of dense, closed rings that are darker in the middle. The fur is soft and consists of long, thick hair. The hair on the back is 20 to 25 millimeters long in summer and 50 millimeters in winter. The winter coat varies from light yellow to yellowish-red with a golden tint or rust-colored to reddish-yellow. The summer fur is brighter and more intense. Because of their light color and large rosettes, the skins were often confused with those of the snow leopard.

- The Caucasus leopard fur and Kuban area :

- Kuban area: Smaller and lighter than the neighboring areas in Asia Minor. Due to the longer hair, dull in color. Without reddish coloring. It lacks the silky, golden sheen of tropical occurrences, as it is already present in the Transcaucasian.

- Caucasus: Large, long-tailed. Hair long, coarse, dense. Basic color very changing; Sides lighter; Belly and inside of legs whitish; Back reddish to rust-colored to gray-yellow, often almost whitish. - There are hardly any skins resembling each other in their defilement. The spots are evenly distributed; very dense and symmetrical in the back, like rose petals, angular to elongated, never self-contained and never circular, largest on the eel line (5 centimeters long, 2.5 centimeters wide); pitch black to dark brown. (Apparently the transition from the bright northern leopard to the more yellowish northern Persian and reddish Asia Minor).

- * Transcaucasian leopard skins , Transcaucasus and western Asia Minor. Large; bushy tail. Shorter in the hair, but longer than with tropical origins. Usually reddish to yellowish, also light reddish to fawn brown, shiny. The rosettes are large, narrowly bordered, evenly distributed. The winter coat strong in the hair.

- * The fur of the Asian leopard , on the other hand, is more tan, often a little gray.

- Africa

Compared to the Asian varieties, the African leopard skins are usually shorter-haired, more yellow in color and more distinctive in their drawing. Sometimes there are black specimens.

Coming from African leopards

- in the north , from Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco. For the most part exterminated. Very large; mostly dark in color, often with a clear shade of gray, but very variable; long and thick in the hair.

- British Somaliland , Jubaland ("baby leopard", trade name for the small spotted specimens). Medium in size (relatively large ears); very short-haired; light brownish to gray-brown to reddish. Silky gloss. Well drawn, the spots larger and further apart, in the shape of a ring and rosette on the sides. Light leather; The treatment of the hide leather on site was particularly good, the hides were particularly suitable for coat purposes. The flat-haired and beautifully patterned specimens of the Somalileopard were the most highly rated leopard skins.

- Inner Abyssinia . Greater; smoker, reddish to very dark. Rosettes mostly large, always with very thick margins, often only full spots on the back. Often black specimens. A little heavy in the leather.

- The Sinai leopard is extinct. The fur was big; very light, pale gray to creamy yellow with a slight shade of gray. Similar in color to the snow leopard. The difference between back and stomach color is very small. Rosettes medium-sized; Hearts hardly darker than the color between the spots.

- North African leopard , Egyptian Sudan. Large, yellowish-ocher, very different in color and pattern. It seems to be very rare in Northeast Africa. Very light-leather, the fur was sold as the "Somali leopard".

- South arabia . Small. Hemprich & Ehrenberg described a very brightly colored animal.

- The Eritrea leopard fur is somewhat smaller and short-haired; silky gloss. The two above-mentioned, very light-leather species have a particularly beautiful markings; like those of the North African leopard, the skins were also sold as the "Somali leopard". Also very light-leather, they were suitable as coat goods.

- The slightly larger fur of the East African leopard , Kenya and Tanzania to Nyassaland. Larger than the Somalileopards. Stronger colored, predominantly bright ocher to tan, rarely yellow-brown, olive-brown or olive-gray. Large spots.

- The Zanzibar leopard is also considered to be extinct. The fur was small, with many small, closely spaced spots; lighter and shorter-tailed than East African leopards.

- The fur of the Central African leopard , Mozambique to Angola , in the south to Orange and Transvaal . Light ocher to almost creamy yellow, lighter than East Africans. The leopards of South West Africa are usually a little more yellowish on average; the hair is stronger.

- The South African leopard skin usually has small rosettes; it is darker than that of the southwest African leopard and is more reddish in color, also described as yellowish tan.

- Uganda leopards from the humid savannas of southern Sudan, Bahr al-Ghazal , Lado enclave , in the south to the Ituri rainforest and Lake Kiwu , in the east to Lake Victoria and Mount Elgon . Very similar to the East African leopard. Large; on average almost a little lighter than East African skins and more spotted, reddish-yellow to tan.

- The Congo leopard lives in the Ituri rainforest, it is smaller and more yellowish. According to another description: dark, olive-gray to tan, always darker than savannah leopards, with small spots.

- Rwenzori region (Uganda). Only two specimens were described until 1964. Mountain leopards of a rather dark olive-brown color with very large, thick-edged spots and dense fur, bushy tail.

- The fur of the Cameroon leopard from the savannahs of the country is larger than that of the forest leopard; it has a strong, luminous color, light brownish yellow.

- The fur of the West African forest leopard , forest areas from Senegambia (the area of today's states Senegal and Gambia ) to Guinea and Gabon . The fur is dark in color, dull; olive gray, olive brown to leather colored. Small, almost closed, close-fitting, deep black rosettes. The hair is short, silky, shiny (in the same description: "dull dark" and "silky shiny").

trade

The delivery of the pelts from the country of origin was mostly not carried out by the fur wholesalers, as with the fur types traded in large numbers, but by people or companies who generally dealt with the import of overseas national products. At times, however, the delivery was significant; it was then made in lots of 20 to 50 pieces. Black panthers were hardly ever on the market and were of no importance for fur processing.

In the early 1960s, a well-known tobacco expert who had attended the London auctions for 50 years gave hints about the world production of leopard fur at the time:

- Most of the seizure was likely to have been traded through the London auctions. Exact figures could hardly be obtained, especially since goods were repeatedly withdrawn and then offered again in the next auctions. China had about 4,000 to 5,000 pelts on the market in the five years prior to 1961. Most of them fell into the 3rd and 4th grades as well as LOW grades, good 1st and 2nd quality skins were seldom lower. Siam -Thailand had an annual yield of around 300 to 500 skins. A few hundred skins fell in Africa. In addition, the buyers from Somali and Abyssinia supplied skins directly to the international market, which was probably another few hundred skins. Deliveries from other areas were insignificant. Those who went on safari in Africa usually kept the fur themselves as a hunting trophy. The expert estimated the total annual volume at around 1500 to 2000 pelts.

The skins were always delivered open, not peeled off round.

processing

The processing of fur for clothing purposes was not easy because of the complicated drawing. Also difficult and time-consuming was the invisible repair ( opening ) of the leopard skins, which were often badly damaged by gunshot holes. It was difficult to put together the finest range of jackets. 4 to 6 well-fitting (harmonizing) leopard skins are needed for a coat. Even within the attack of Somalileopards, for example, the skins are not uniform. They must be similar in terms of hair quality, color, shape (shape) and arrangement of all the figures in each coat (pattern, drawing). If only one head did not meet this requirement and a suitable replacement head could not be obtained, then all other pelts intended for a coat could not be used in the desired way and under certain circumstances lost considerable value.

The furs that are occasionally still available today are used as hunting trophies almost exclusively, possibly with naturalized heads, made into rugs.

Numbers and facts

The earlier annual world incidence of leopard pelts occasionally mentioned in the fur literature must always be viewed with reservation. In Emil Brass , who last listed important figures on the occurrence of the various types of fur in 1925 , the individual occurrences are so small that they cannot be reconciled with the total amount of 30,000 pieces he apparently estimated. Other, later numbers, on the other hand, are again so low that they were apparently hardly sufficient to cover the apparently large supply in the trade. According to Lübsdorf, there were 50,000 skins in 1960 . Official production statistics for the countries of origin did not exist and only some of the goods took the route from collectors to wholesalers and auction houses, which is usual in countries with a large amount of fur animals from the wild. In addition, there were skins from animals that had been hunted without a permit. All supraregional statements are therefore based on very rough estimates, supported by little data.

- In 301 AD , Diocletian issued the maximum price edict , the violation of which was punishable by the death penalty. It also lists the prices for raw and trimmed hides: converted to 1922, a denarius was worth 1,827 German pfennigs.

| Roman denarii | Roman denarii | |

|---|---|---|

| raw | prepared (tanned) |

|

| Goatskin , great | XL | L. |

| Sheepskin , great | XX | XXX |

| Fur for hats | C. | |

| Finished cap | CC | |

| Lamb or kidskin | X | XVI |

| hyena | XL | LX |

| Deer fur | X | XV |

| Deer skin | LXX | C. |

| Wild sheepskin | XV | XXX |

| Wolf skin | XXV | XL |

| Marten fur | X | XV |

| Beaver fur | XX | XXX |

| Bear fur , great | C. | CL |

| Lynx fur | XL | LX |

| Sealskin | MCCL | MD |

| Leopard skin | M. | MCCL |

| Lion skin | M. | |

| Eight goat skin blanket | CCCXXXIII |

- 1913 , quote: EH Wilson met a column of 5 men who were carrying more than 100 leopard skins while hiking in the valley of the upper Minriver (west of Szetschuan ) in 1913 . These came from Kuetschou and Yünnan . The skins were intended for Sungpan . There they should be used for robes (see the article fur scraps ) and belts .

- Before 1914 , before the First World War , African leopard skins were rarely traded for more than 20 to 30 marks (Brass). They were only used for blankets and carpets and were therefore less valued than the Chinese leopards.

- In 1924 , when skins were now in demand for coats, 150 marks were paid for the skin (Schöps quote from Brass). In his work from 1925, however, Brass gives 60 to 80 marks for the piece, with an annual volume of 1000 to 2000 pieces, for the northern leopard an updated price of 50 to 100 marks compared to the book edition of 1911 ( 1911 : 30 to 50 Mark), that of the southern leopard with 30 to 50 marks ( 1911 : 10 to 25 marks). The annual export was about 300 northern, 600 southern and 100 Korean skins ( 1911 : unchanged number of pieces).

- In 1934 , the former diamond dealer Lepow in the Transvaal received from the Emperor of Abyssinia Haile Selassie I as the first white man the trade permit for the interior of the country. 18,000 leopards were killed that year, up from 8,000 the year before. 4000 came from Abyssinia and the Belgian Congo, 4000 from Somaliland.

- In 1959 , good Somali leopard skins cost £ 35-45 in London. Some of the pelts did not always come out of the fur trim perfectly and were therefore unsuitable for processing the coat. For the calculation, this resulted in significantly higher prices for usable coat skins, including fur finishing .

See also

literature

- Burchard Brentjes : The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. In: The fur trade. Writings for fur and mammal studies. Volume XVI / New Series, Volume 1965, No. 6, Hermelin-Verlag Paul Schöps, Berlin et al. 1966, pp. 243-253.

annotation

- ↑ The specified comparative values ( coefficients ) are the result of comparative tests by furriers and tobacco shops with regard to the degree of apparent wear and tear. The figures are not unambiguous; in addition to the subjective observations of durability in practice, there are also influences from fur dressing and fur finishing as well as numerous other factors in each individual case . More precise information could only be determined on a scientific basis. The division was made in steps of 10 percent each. The most durable types of fur according to practical experience were set to 100 percent.

Individual evidence

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 247; Secondary source: J. Mellaart: The Excavations at the Catal Hüyük . 1961. In: Anatolian Studies . No. XII, London 1962, panels XIV, XV, XVI etc.

- ↑ a b B. Brentjes: On the fur costumes in African rituals . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 4, New Series, vol. XXI, Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 21-22.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 245; Secondary source: ED Philips: The nomadic peoples . In: S. Piggott: The world from which we come. Munich 1962, p. 315 ff.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 245; Secondary source: ED Phillips: The Nomad Peoples . In: S. Pigott: The world we come from . Munich 1962, p. 315 ff.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The oldest surviving boot made of leopard skin . In: Das Pelzgewerbe 1966 No. 4, Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 172-173.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 247; Secondary source: A. Champdor: The ancient Egyptian painting . Leipzig 1957, pp. 103, 151 and others

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 245; Secondary source: FS Bodenheimer: Animal and Man in Bible Lands . Leiden 1960, p. 174.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 247; Secondary source: J. Mellaart: Excavations at Catal Hüyük , 1962. In: Anatolian Studies. Volume VIII, London 1963, pp. 43-105, Figure 29.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 245; Secondary source: H.-L. Gautier: Sacophage No. 6007 de Musee du Caire . In: Annales du service des antiquités de l'Egypte . Vol. 30. 1930, pp. 174-183, panels I and III.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 248; Secondary source: W. Wreszinski: Atlas on Egyptian cultural history . Leipzig 1936, vol. 3, in plate 334.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 248; Secondary source: W. Wreszinski: Atlas on Egyptian cultural history . Leipzig 1936, vol. 3, in plate 224.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 246; Secondary source: A. Parrot: Le Temple d'Ishtar . Paris 1956, Figures 79, 80, 82, 83, 89.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 248; Secondary source: W. Wreszinski: Atlas on Egyptian cultural history . Leipzig 1936, vol. 3, in plate 127.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 248; Secondary source: A. Champdor: The ancient Egyptian painting . Leipzig 1957, plate 107.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 248; Secondary source: W. Wreszinsky: Atlas for Egyptian cultural history . Leipzig 1936, vol. 3, in plate 158.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The leopard skin in the ancient Orient. Berlin et al. 1966, p. 248; Secondary source: W. Wreszinsky: Atlas for Egyptian cultural history . Leipzig 1936, vol. 3, in plate 300.

- ^ The Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. The Howard Carter Archives: Leopard-skin cloak , Carter No .: 021t, Photo Harry Burton: p0422, accessed August 22, 2014

- ^ The Griffith Institute. Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation. The Howard Carter Archives: Remains of a leopard-skinrobe , Carter No .: 046ff, Photo Harry Burton: p0009, accessed August 22, 2014.

- ↑ a b Elizabeth Ewing: Fur in Dress . Batsford, London 1981, pp. 72, 102 (English)

- ↑ Paul Cubaeus, Alexander Tuma: The whole of Skinning . 2nd revised edition, Hartleben's, Vienna / Leipzig 1911. pp. 50–51.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: To the fur costumes in African rituals . Primary source: Helmut Straube: The animal disguises of the African indigenous people . In: Studies in cultural studies. Vol. 13, F. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1955.

- ↑ a b c d e Emil Brass: From the realm of fur . 2nd improved edition, publisher of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925, pp. 485–489.

- ^ John C. Sachs: Furs and the Fur Trade . 3rd edition, Pitman & Sons, London undated (before 1923), p. 67 (English).

- ↑ Ralf Krüger: Zulus in leopard skin are viewed critically. ( Memento of the original from May 2, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: news.de from April 15, 2004; last accessed April 29, 2009.

- ↑ Evans-Pritchard

- ↑ Elizabeth Ewing: Fur in Dress. Pp. 76-77. Secondary source: WY Carman: Dictionary of Military Uniforms .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Paul Schöps in connection with Kurt Häse, Richard König sen. , zoological processing H. Dathe, Ingrid Weigel: The leopard and its fur . In: Das Pelzgewerbe, Volume XV / New Series, No. 1, Schöps, Berlin et al. 1964, pp. 5–23: The information (on varieties and provenances) comes from literature, experienced zoo gardeners and tobacco wholesale .

- ↑ 1837 p. 9, 1835 p. 12

- ↑ Schöps: The leopard and its fur. Pp. 21-23. There are no originals of such saddlecloths in the Vienna Museum. According to a present illustration, the drawing of the fur is more that of a leopard than a tiger, since the latter is striped lengthways. --- There is an original of the saddlecloth of the Hungarian bodyguard . The drawing of the fur (leopard, panther) corresponds to the illustration of the "tiger skin" mentioned above .

- ↑ a b Eva Nienholdt: Fur in the war costume and uniform . In: Das Pelzgewerbe / Volume IX / New Series, No. 6, Schöps, Berlin et al. 1958, pp. 271–276.

- ^ Richard Knötel: Handbuch der Uniformkunde. Books on Demand (BoD), 2013, ISBN 978-3-8460-3334-0 , p. 454 ( at google-books ).

- ↑ Nienholdt: Fur in the war costume and uniform . Secondary sources: François Xavier Martinet: Historique du 9e régiment de dragons. Editions artistiques militaires de Henry Thomas Hamel, Paris 1888, plate 2; Richard Knötel, Herbert Knötel, Herbert Sleg: Handbuch der Uniformkunde. The military costume in its development up to the present day. Schulz, Hamburg 1937, p. 175f, fig. 66.

- ↑ Economic Encyclopedia online. Johann Georg Krünitz: Economic encyclopedia or general system of the state, city, house and agriculture. Volume 57, 1792, chapter furriers, 15. Die Tieger = skins .

- ^ H. Werner: The furrier art . Voigt, Leipzig 1914, p. 91.

- ↑ a b c Paul Schöps: Fellwerk der Großkatzen . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Neue Episode, vol. XXI, No. 2, Schöps, Berlin a. a. 1971, pp. 4, 17-24.

- ↑ Herbert Zippe: The little book of fur . Pinguin-Verlag, Innsbruck, 1971, p. 29.

- ^ A report from the Banco di Roma: Ethiopia and its fur production . In: The tobacco market. No. 31, Leipzig August 6, 1937, p. 1.

- ^ A b Max Bachrach: Fur. A Practical Treatise. Prentice-Hall, New York 1936, pp. 193-198 (English).

- ↑ Anna Municchi: Ladies in Furs 1900–1940 . Zanfi, Milan 1952, English, ISBN 88-85168-86-8 .

- ↑ Philipp Manes : The history of the German fur industry and its associations. Volume 3. (copy of the original manuscript), Berlin 1941, p. 126 (→ table of contents) .

- ↑ Bob Dylan: Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat. ( Memento of the original from September 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Lyrics (English) On: bobdylan.com , last accessed on September 22, 2014.

- ^ Chico, Beverly: Hats and Headwear around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia . ABC-CLIO , 2013, ISBN 978-1-61069-063-8 , pp. 378-379.

- ^ Gill, Andy: Bob Dylan: The Stories Behind the Songs 1962-1969 . Carlton Books, 2013, ISBN 978-1-84732-759-8 , pp. 144-145.

- ↑ a b c Arthur Samet: Pictorial Encyclopedia of Furs . Arthur Samet (Book Division), New York 1950, pp. 324-329. (English)

- ↑ Alexander Tuma jun: The practice of the furrier . Springer, Vienna 1928, p. 236.

- ↑ Bruno Schier : Ways and forms of the oldest fur trade . (= Archive for fur customers. Volume 1). Schöps, Frankfurt am Main 1951, p. 28. Table of contents .

- ↑ Shannon Bell-Price, Elyssa Da Cruz: Tigress . In: Wild Fashion Untamed . The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2005, p. 123. ISBN 1-58839-135-3 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); ISBN 0-300-10638-6 (Yale University Press).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Christian Franke, Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel 's smokers manual. Animal u. Fellkunde (= archive for fur and fur science. Vol. 310). Revised and supplemented new edition, Rifra-Verlag, Murrhardt 1989, pp. 88–90.

- ↑ a b c d Heinrich Dathe , Paul Schöps, with the assistance of 11 specialists: Fur Animal Atlas . VEB Gustav Fischer, Jena 1986, pp. 218-220.

- ↑ Fritz Schmidt : The book of the fur animals and fur . Mayer, Munich 1970, pp. 146-148.

- ↑ Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse: The fineness of the hair. The fineness classes . In: The fur industry year. VI / New Series, No. 2, Schöps, Berlin a. a. 1955, pp. 39–40 (note: fine (partly silky); medium-fine (partly fine); coarser (medium-fine to coarse)).

- ↑ Paul Schöps, H. Brauckhoff, K. Häse, Richard König , W. Straube-Daiber: The durability coefficients of fur skins . In: The fur trade. Volume XV, New Series, No. 2, Schöps, Berlin a. a. 1964, pp. 56-58.

- ↑ K. Nowell, P. Jackson: Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN / SSC Cat Specialist Group, Gland CH 1996.

- ↑ Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition, published by the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, pp. 401–406.

- ↑ Bahram H. Kiabi, Bijan F. Dareshouri, Ramazan Ali Ghaemi, Mehran Jahanshahi: Population status of the Persian Leopard (Panthera pardus saxicolor Pocock, 1927) in Iran. In: Zoology in the Middle East. No. 26, 2002, pp. 41-47. ( Full text as PDF file ).

- ^ VG Geptner, AA Sludskii: Mlekopitaiuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Vysšaia Škola, Moskva 1972. (In Russian); English translation: V. G, Geptner, AA Sludskii, A. Komarov, N. Komorov: Bars (Leopard). 1992, pp. 203-273 ( at Google books ) In: Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2: Carnivora (hyaenas and cats). Smithsonian Institute and the National Science Foundation, Washington DC 1988.

- ↑ Paul Schöps among others: Snow leopard and clouded leopard . In: Das Pelzgewerbe, Volume X / New Series, No. 3, Schöps, Berlin et al. 1959, p. 103.

- ^ Author collective: Der Kürschner . Technical and textbook for the furrier trade. 2nd revised edition. Published by the Vocational Training Committee of the Central Association of the Furrier Handicraft, Bachem, Cologne 1956, p. 235.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: The history of the skinning . Tuma, Vienna 1967, p. 47.

- ↑ Schöps: The leopard and its fur . P. 12; Secondary source: Karl books: contributions to economic history . Tübingen 1922, p. 222.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XX. Tape. Tuma, Vienna 1950, keyword “Leopard”.