Bird skin

As a bird hide in is fur industry the withdrawn, feathered skin of a bird called. In the last few decades, however, bird skins were no longer used to any significant extent in the manufacture of clothing. As early as 1970, their use was mentioned as "only relatively seldom as a set for dressing gowns or party clothes for teenagers".

Bird skins, like mammal skins, can be made durable by tanning , but were considered "a little durable fur". Only those species were considered that have a full and well-developed chest and stomach plumage, because this "keeps you warm, is supple, light and silky soft and is also very appealing with its white or light colors full of high gloss". In contrast to the production of almost all mammal furs, bird skins were cut open on the back to protect the better belly side.

Since the feather is significantly superior to the hair as a heat insulator , feather skins were used in extremely cold areas, despite the low durability , even where fur animals were abundant. In particular in coastal areas and on the islands of the far north this was the case "early", where not only birds but also seals , arctic foxes , polar bears and other mammals were hunted for the production of fur. Eider ducks , grebes , geese , gulls and swans were the main suppliers of the bird skins .

Especially between around 1840 and 1890, furriers in the cities of Europe and North America processed the skins of some bird species to a significant extent into clothing. At the time, young women wore a set consisting of a beret , a matching small muff and a narrow tie made from the shining white chest and belly plumage of the grebe (at the time called 'hooded tailfoot') , which ran into blue-gray or reddish brown on the sides .

Since the emergence of modern biology at the end of the 18th century, feathered bird skins, which are also known as bird hides, have been preserved by biological taxidermists and partly processed into whole-body preparations for research and teaching purposes. In ornithology, bird hides are an important source of information for species identification and definition . In addition, "stuffed birds" are also used for decoration.

history

In the Hermitage Museum St. Petersburg , a 60 centimeter is long and 30 centimeters wide skirt made of bird skins from Buryatia [Buryat], Siberia, which has been dated to the first century BC, according Gorbatcheva / Federova.

The German scholar Adam Olearius published a description of the Muscowite and Persian journey in 1647 . He expanded the 2nd edition with a whole chapter on the Eskimos, their clothing, customs, language, their trade, etc. His thorough presentation is the first detailed description of the Greenlanders and their way of life: “As for their clothes, they are made of seals and reindeer skin , the coat of which is turned inside out like the Samoyed . Inside, they are lined with bird skin, especially swans, wild geese, ducks and seagulls. In summer the feathers are also turned inside out ”.

In southern Greenland , Inuit men have long worn long fur around their upper body, the so-called timiak , which is mostly sewn from the fur of the eider . The rigid cover feathers are plucked out so that only the soft down remains. A hood edged with dog fur was attached to these shirts . Fridtjof Nansen wrote that the skins of cormorants were also used, as well as those of Nordic jackdaw species when sailing in the kayaks . It was reported that the albatrosses accompanying the ships in the southern seas were often caught by the sailors to make warm blankets out of the skins. The plucked skins of the mostly vividly colored eider ducks were used in a similar way in Norway and Sweden. Skins from eider ducks, guillemots and other birds were used by the Eskimos for stockings and slip-ons when caribou skins were not available. Birdskin slippers require little sewing. Birdskin hats were worn on the Québec - Labrador Peninsula , where Inuit and Innu ( Naskapi and Montagnais Indians) live together.

The Eskimos often kept the tendons for sewing their clothes in a pouch made from bird hide; in the early 1990s this was still in use by some women of the Sanikiluaq . To do this, the skin of a loon was pulled off, which then looked like a tube. The leg and wing holes were sewn up. A piece of seal skin or fabric was sewn onto the remaining opening as a finish. The tendon pouch was used with the feathers inwards to protect the tendons from drying out and hardening.

It is said of the Samoyed in western Siberia in 1776:

- The winter clothes are usually made of reindeer fur, fox or other fur, mostly with white, long-haired fur from dogs or wolf bellies, sometimes also from the bellies of divers and other water birds, always folded over one another, the hair or feathers facing outwards and with a belt around it Body attached. Some of the feathers and fur dresses are often frangled in the Yakut fashion with long dyed hair and stitched.

The use of bird fur is also known from the Aztecs .

In contrast to the inhabitants of cold areas, such as Eskimos and Tierra del Fuego , who always made their feather clothing from whole furs because of the better warming effect, the sometimes splendid feather clothes of the South Sea inhabitants were not made from bird skins, but woven from plucked wing feathers.

For Germany, a description of the various professions from 1762 states: “The Kirschner's materials come from such a vast animal kingdom, with the restriction that he only uses the hairy four-legged animals from it”, but a few pages later are listed as “the most elegant Felle ”mentions the swan skins, which are used to make“ women's muffles ”. Other bird species are also mentioned there. In Holland, where the most beautiful swan skins came from, an industry of its own was still engaged in the extraction of swan skins and the production of swan skin trimmings in the 1920s.

In Scandinavia, the skins of young eider geese and eider ducks were "put together to make beautiful blankets in all shapes and sizes, to which edges from particularly colorful bird species are added to embellish and complete, and which blankets are particularly popular with foreigners visiting the far north" (1895) . The furrier Hanicke wrote at the time that the bird necks of the so-called fin divers and the magnificently shimmering green cormorants, the penguins, and the so-called black-and-blue crayfish or scoter ducks were also processed in the same manner.

In western fashion, bird skins were mainly used for small items such as sleeves, scarves, trimmings on clothing and headgear, and for collars and trimmings. In children's fashion, they played a very important role at times with the same use. In the 19th century, small women's capes were also often made from them. When fashion preferred longer and bulkier capes at the end of the century, bird skins were less used for them, because capes made from grebe's skins would have been too heavy and not pliable enough.

In the mid-1950s, Marlene Dietrich appeared in London in a transparent chiffon dress that was embroidered over and over with Rhine pebbles and other rhinestones ; above it a huge stole made of swan fur by Christian Dior . When she came back to Germany for the first time after emigrating in 1960, she wore a highly acclaimed "swan fur" made from "5000 swan down" at a performance in West Berlin's Titania Palace . This coat, too, is not made of individual down, but is made of plucked bird skins and fabric. After throwing an egg on her person, she replied to a reporter if she was afraid of an attack: “Afraid? No I am not afraid. Not of the Germans, just about my swan coat, from which I would hardly get egg or tomato stains, I'm a little afraid. "

Clara Schumann's swan fur is less spectacular and less well known . The meanwhile badly damaged cape of the German pianist and composer, wife of the composer Robert Schumann , is now in the Heinrich Heine Institute in Düsseldorf .

- Bird skin clothing of Nordic peoples

Aleutians , a parka called "Sax" from Grebes (feathers inside?) Trimmed with sea otters (Anchorage Museum of History and Art)

Nunivak , mother and child (1928)

Yupik , mother and child (1929)

Greenland , men's hat (1999)

Bird species used for processing into clothing (among others)

In addition to those listed below, other waterfowl also have plumage suitable for fur purposes. The skins of the goose saws, for example, are also beautiful. The meat of a bird living in the Holarctic was consumed by the inhabitants, the fur was also consumed locally.

Eider

The body length of the eider is on average 58 centimeters. The breeding plumage of the male bird is predominantly white on the back and chest, with a hint of pink on the chest. The belly, the flanks, the middle of the rump , the tail, the upper and lower tail and the top of the head are feathered black. The feathers on the neck are light moss green and slightly elongated so that they form a small hollow . The outer arm wings are black, the inner ones are white and curved like a sickle. The banding of the plumage is a little less noticeable than that of the females. The female has an inconspicuous dark to yellowish-brown plumage throughout the year, through which dense black plumage bands run on the body. The neck and head, on the other hand, are more monochrome brown. The plumage there has only a fine, brown-black dash.

Young birds of both sexes resemble the females in their plumage. However, they are slightly darker in their plumage color and less strongly banded. Young drakes wear the fully developed splendor of the male in the 3rd or 4th year of life. Even when they are 2 years old, they clearly show the black and white contrast that is typical for adult drakes. At this point there are still feathers with a yellow-brown edge in the head and neck area. Parts of the dorsal plumage are still black-brown.

Eider ducks were hunted so heavily because of their fur, but above all because of their feathers, that by 1900 Iceland and Scandinavia had already enacted protective laws. In the years up to 1910, however, around 3,000 kilograms of down were collected annually from the nests padded with it in Greenland alone; 24 nests yielded around one kilogram. “Grass dunes” were valued more highly than the often polluted “seaweed dunes”. It takes one and a half kilograms to fill a duvet with it.

Apart from the springs freed from the upper springs skins were used at the time and occasionally to Pelerinen to make and collar it. By “carefully juxtaposing the dark wing parts” one sought “to achieve a pleasing drawing”. The Eskimos made slippers from eider duck skins, which were well suited for hunters who had to stand on the ice in the cold. However, these Eskimo footwear was less durable than those made from caribou or seal skin.

King eider

The king eider is slightly smaller than the eider. The drake is unmistakable with its black-colored body, white to salmon-colored breast and light blue top of the head and neck. The neck feathers are slightly elongated, so that a spring hood appears. The cheeks are sea green, the chin and throat white. The black plumage of the rear part of the body is sharply defined by a narrow white side band and an almost round white spot on the rump sides. The sides of the head and the front breast are light cinnamon brown. The rest of the body plumage is dark brown to black brown. The female has brown plumage. However, it can easily be distinguished from all ducks except for other eiders by its size. Compared to the females of the eider, the plumage of the females of the king eider is more reddish and the body plumage is not banded, but with the exception of the head, looks like scales. The chest and the underside of the body are black-brown. The female's resting plumage resembles the breeding plumage. However, the color contrasts are somewhat weaker and the scale-like pattern of the body plumage is less noticeable.

In 1950 the fur lexicon noted that the feathers of the feathers of the king or king eider duck native to Scandinavian countries were plucked before tanning, only the dense, light gray down hair was left. The skins were made into blankets by Norwegian and Swedish furriers "in high mastery", which were lined with the light green neck sections and "make a very pretty impression". "But the Eskimo women also make excellent blankets from it, for which good prices are paid."

Diver

As divers will find different families of water birds - grebes (Grebes), loons and Alken - summarized.

Grebes (grebes) and loons

The Grebes most frequently used were the Little Grebes and the Little Russian Grebes with a white, dense, silky-shiny belly, which in some breeds appears to be mackerel with individual brown feathers. After the wings the color changes into black, gray-yellow or red, the skins were sorted accordingly. There is a little red head of feathers behind the ears. The fur is 20 to 22 centimeters tall and, like all bird species, was cut open because of the nicer belly side in the back, which then forms a red side.

The large Grebes ( grebes ) were blue-gray, however, beautiful not only for its size but also because of its, depending on the type, steel-gray to schwärzlichgrauen back staining preferred.

The small red-sided varieties (probably from ear divers ) are native to northern Europe and at least at that time came down to Brandenburg, as well as in Russia and Siberia. The large or blue-sided Grebes live in Turkey, Asia Minor and the Balkans. Holland, Denmark, and Sweden delivered cruel sides; from the Swiss lakes and from Russia came especially yellow and red-sided varieties, while in the countries of the Mediterranean there are mainly smaller and tabby varieties. The most beautiful skins came from Greece, Italy and Switzerland, the lesser, not so beautifully shiny ones from southern Russia ( Caspian Sea ). Nevertheless, Russia supplied most of the Grebe's skins, in the small town of Tjukalinsk , not far from Omsk , collecting and shipping the skins was a large branch of industry. Furs also came from the fairs in Ishim and Petropavlovsk . Almost only European furs were traded, California supplied a certain amount of large black-sided furs (possibly from racing divers ); A small amount of Grebes came onto the world market under the Spanish name “Macas”.

A specialist furrier book from 1844 mentions grebenhkins only as originating from the great crested grebes living in Switzerland on Lake Geneva and Lake Neuchâtellers , as well as those from Normandy , which are of weaker quality than those from Switzerland.

The trade actually only differentiated between blue and red-sided types, as well as large and small skins, which were used especially for trimmings and children's sets.

Grebes fashion was most important in Germany in the 17th century. Even in the 19th century the consumption of the grebes' skins was still considerable. Seagull and grebe skins were "novelties whose appearance was inextricably linked with beret fashion ". They were imported in quantities of hundreds of thousands, especially from Russia and Siberia, but also from the Balkans, Holland and even California (the latter were described by the tobacco shop Emil Brass as “perhaps the best there is”). Grebesskins were suddenly asked again later, as collars for black satin coats . The fur lexicon from 1949 still reports on a total of "several hundred thousand pieces annually"; it can be assumed, however, that there were already considerably fewer at the time.

Men's clothing made of diving bellows was available from the Chukchi Siberia and the Koryaks in Kamchatka.

Crab Grebes

Children's fur trimmings made from the skins of the crab divers were particularly popular. The Eskimos sometimes used them for children's slippers.

Puffin

In earlier times the men of the Aleutians wore an item of clothing adorned with goat hair and made from the very firm hides of the puffin .

Goose (domestic goose)

The plumage of the domestic goose originally had white to brownish-gray hues; in the male bird it becomes whiter with age. By breeding selection, the feathers became more and more pure white according to market demand. The goose's fur has usually been freed from the upper feathers, and it then forms a fairly even, white, fluffy surface. It came on the market as "swan trimmings" and was mostly made into collars.

The best, because the thinnest and most indifferent in the leather and the most densely and lusciously feathered, came from Holland, where they were also bred especially for fur purposes. The skins from France were less fine and dense and not so good in the leather, and those of the German land geese were even thinner. The goose quills served as quills.

In 1914, a specialist book noted: Recently, gorgeous-looking "swans" made from Dutch goose fur are used as a chic prop for a trip in a zeppelin - probably the most sensible use, especially for the fur of a bird that cannot fly itself. In 1936 swan skins were only used for fur purposes in Holland and in parts of Poitiers in France, namely as "trim" (decoration).

Albatross

At the end of the 19th century, albatrosses served as spring suppliers for clothing linings and pillow fillings. Several colonies comprising hundreds of thousands of birds were destroyed within a few years. Well over a million short-tailed albatrosses were killed between 1887 and 1903, bringing the species close to extinction and making it so rare that it has been unable to recover from this persecution to this day.

A so-called barrel muff made of albatross fur with white and pale brown feathers from New Zealand from the late 19th century is shown opposite, with a muff warmer in front of it.

kingfisher

"Gröbis" was the name given to the kingfisher , whose bellows were used for children's and girls' sets.

Falcon

The sacred bundle of war clubs was of great importance to the North American Wineboa Indians ( Sioux ). He was credited with the power to bring victory in battle with his charged magical powers, which had their seat in the many parts of the bundle. In an example in the Munich Ethnographic Museum in 1937, the main figure is the belly of a falcon , wrapped in the fur of a deer fetus and decorated with porcupine bristles. In addition, the shell made of buffalo calfskin and plaited mat contains some red-dyed eagle down, a bunch of falcon feathers, an otter skin , ermine hides with a medicine bag, buffalo and skunk tails , the skin of a snake, the claw of a grizzly bear , fire drill and sponge, pipe flutes and drumstick, bag with Herbs, the rest of a leather quiver, a warrior doll and a headdress. A war club and tomahawk are attached to the bag .

vulture

In 1844 the vulture was described as a prized fur with gray, extremely soft fur and warm fluff. Another furrier textbook 67 years later said that although the fur is seldom seen, there are lovers for the long, fluffy skin, regardless of gray but also gray and white mottled.

cormorant

According to Emil Brass, the only countries where the skins of the cormorant, which was heavily persecuted as a fish predator, were used were Norway and Sweden. At the beginning of the 20th century, the furriers there made muffles, capes, stoles, etc. and even coats from cormorant skins in the same way as they did from eider duck skins, the latter being “bought as strange fur” by tourists.

At the Prussian purveyor to the court E. Brandt in Bergen , Norway , from where the emperor used to bring presents from his trips to the north, a cormorant coat cost about 1,000 crowns. In 1932 C. Brandt commented on an article about “a special sight”, an extraordinarily supple and light cormorant coat presented in London, which is said to be of poor durability: “As the sole manufacturer of cormorant coats, which I have been manufacturing for over 50 years, I would like Let me tell you that the durability of the coats, jackets, scarves and trimmings made of cormorant is astonishing. After 20 years of wear and tear, I got coats to refurbish, which after cleaning and repairing less scraped edges etc. Ä. were indistinguishable from new pieces and could be extended with fresh pelts. There is little other fur material that such a test would stand up to as well. "

The color of the cormorant is probably always darker and gray-brown and the down fur is much looser than that of the eider.

parrot

The hides of parrots were worn as hair accessories in New Guinea .

Bird of paradise

On the Moluccas , the girls used the bird of paradise hides as hair ornaments. In some parts of New Guinea , birds of paradise were used as currency.

pelican

In 1930 it was mentioned that pelican fur was becoming increasingly popular. However, it was restricted that it would only be considered for some countries, such as for certain areas of Asia and sometimes particularly southern Russia. As an export product, the freight charges made it so expensive that the price in Central Europe was out of proportion to the actual value.

gull

Around 1900 the following was stated for the use and processing of the skins of the seagull in skinning: “Ladies hats, sleeves, collars and children's sets. Often the heads are naturalized and wings and tails are used. As with the Grebes, when working with seagulls, the sides are usually placed on flat fur, such as white or blue rabbit, for greater durability and a better finish ”. At the world exhibition in Vienna in 1873 one could see the use of the most diverse bird species, which today seem strange to us. Mentioned, among other things, was a “carpet made from the wings of seagulls” and a “carpet made from a pelican” from the New York company M. Mahler, but also a women's muff and collar made from seagulls from the company ME Heinrich from the Russian city of Archangel . At the end of the 19th century, the kittiwake was regularly hunted on Heligoland because hats, muffs and women's hat decorations were made from the skins. Of the different types of seagull skins, the blue or gray colored ones were used in particular.

penguin

The penguin skin was mentioned in a furrier handbook in 1895. However, Brass wrote in 1911 that the various attempts to use the skins were in vain. Despite the beautiful appearance and size, they were of no use because the feathers, including the belly feathers, are much too stiff and hard. The emperor penguin pelts were mainly used for bedding.

However, the inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego used to make coats from penguin skins.

heron

The Tuyuka (Dokapuara) in northwestern Brazil wore very elaborate headdresses for their dances. For this purpose, among other things, the hair on the back of the head was combined into a tuft, which was lengthened by an artificial braid made of monkey hair cords. A jaguar bone was tied over the end of the braid, which served as a hold for thick bundles of monkey hair cords and feather bellows of the white heron , which hung long over the back.

swan

The swan skins processed into fur came from three species, the mute swan , the wild or whooper swan and the black mourning swan , in earlier times, when it was still common and not strictly protected, also the North American trumpeter swan .

The swan skins came mainly from Holland, where swans were also bred for feathers and fur, and from France. They are very light, the fur length is 70 to 80 centimeters. The down is very fine, soft and dense; mostly snow-white, some with a light gray tone.

Before 1883, the skins of the mute swans cost 12 to 24 marks a piece, those of the whooper swans were almost as expensive, for the skins of the black swans even 75 to 100 marks were paid.

The strong upper feathers were also plucked out of the swan skins, so that only the soft down remained. They were used almost exclusively as trimmings for ball or theater toilets or for children's items. Up until the First World War, they were a popular material for glossy atlas sleeves or feather boas . After the discovery of aniline dyes , swan pelts began to be dyed purple around 1863.

Around 1800 it says in a picture book for children: "The whole peeled skin with the fine plum feathers is made up, gives a delicate, very warm fur." Philip III. von Rieneck owned a breast cloth lined with swan skin. In various fairy tales, swan fur is reported, with which, for example, enchanted virgins could turn into swans again by slipping on it.

White-tailed eagle

Some tribes on the Asian east coast knew how to make clothes from the skins of the sea eagles .

woodpecker

The Californian Pomo Indians made very elaborate baskets for ceremonial purposes. The exterior was often covered with a feather fur, which was decorated with feather hangings. The upper hem of the work baskets was often decorated with the black feathers of the quail . It is estimated that the feathers of 80 birds were required for the hem, and around 80 woodpecker scalps for the feather fur . More carefully made baskets, in the feather cover of which a pattern of other feathers, for example ducks, magpies , warblers , pouch star , red-headed woodpecker , etc. were incorporated, were especially used as wedding gifts.

The Hoopa, also from California (Northwest California), wore very elaborate ceremonial headbands for the dance of the “White Deer” and the “jumping dance” . The bandages showed a mosaic of stripes of white deer skin, shiny metallic duck skins and scarlet woodpecker head skins. The red-headed woodpecker's head bellows also served them as a means of payment, they were kept in a beautifully carved elk horn box. With the neighboring Californian Karok Indians , each woodpecker scalp is said to have had a value of 20 Reichsmarks (according to Ilwof, 1882).

Tangare

For the Taulipang (Taurepan) in the Sierra Pacaraima of South America, back and breast decorations were common, for example from necklaces, cotton cords to which tufts of white downy feathers were attached, wings of the white heron, etc., or from the hides of the seven-color tangar .

Turkey

The women of some North American Indian tribes made clothing from the hides of the turkey (" turkey "). To do this, they attached the skins to a piece of birch bark.

Toucan

The South American Makusi Indians ( Roraima , Guayana ) adorned themselves with a collar made of mammalian teeth, on which tassels from the bellows of the toucans hung as back ornaments .

pheasant

Pheasant skins are used for hat trimmings. On a photo of an undated stele by the artist Inge Prokot (* 1933), in addition to various other natural materials, some parts of the pheasant skin can be seen.

humming-bird

In 1878 a single company in Leipzig had 800,000 skins from divers , 300,000 wings from snipe birds and 32,000 skins from hummingbirds in stock. For a pair of women's shoes decorated with hummingbird skins, 6000 gold marks were paid.

Ostrich and other large birds

Occasionally, the skins of larger bird species were made usable for the fur trade. The more than 1 ½ meter long “ emus ” pelts came into the trade from Australia , mostly for carpets (up to “a few hundred” a year). At the World Exhibition in Vienna in 1873, the H. Kohn company from Victoria in Australia showed a muff and a collar made of Victorian emupelz .

The Tehuelche , the southernmost Indians of South America, often even made cloaks from the skins of the rhea.

" South American ostriches " were exported in blanket form and as skins and used as "carpets, canvas corners, etc.". Nor did they constitute a large article of commerce.

Regarding the African ostrich , the largest living bird, a handbook for the hides trade in 1956 notes:

- Salted, canned pelts are 6 to 9 square feet in size, and 2nd grade pelts are slightly smaller (5 to 8 square feet). The goods are loaded in sacks.

- Dry skins range in size from 5 to 8 square feet. The quality of dry skins is worse than that of salted ones. The goods are loaded in bales. The African goods are more flawed (sleek, damaged by cuts), if only because they are not slaughterhouse goods.

Women's cap with a prepared bird of paradise ( Edwardian era , Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History)

Birdskin Cape with Mole Fur Yoke (1895, Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute)

Eider duck cap (Brandt Company, Bergen , Norway, around 1900)

Processing for clothing purposes

The preparation of the bird skins after they were peeled off by the Eskimos was quite unusual in our opinion. As with other types of fur, the fat was scraped off the leather with the teeth and chewed off. However, the fat was removed from the leather by a process not unlike the baby's suckling on the bottle. Silatik Meeko reports from the Belcher Islands : “Beginners quickly learn not to suckle too hard, otherwise the feathers will get into your mouth through the skin. But if you don't suck enough, the skin becomes moist. It takes about two hours to prepare a skin so that it feels dry ”.

Outside the Arctic, the utilization of bird skins differed fundamentally from the fur trimming of mammalian skins. Sliced geese or swans were, after they had dried, freed from the coarsest fat and brushed with salt water. When they were soaked, they were fleshed out, pickled for a few days and then dried, then the quills were plucked out. After a light pimple (a type of tanning) the skins were stretched, the particularly fat areas were coated with wet clay and exposed to the sun to dry. Then they were in clay and plaster purified and then knocked , but not with the otherwise usual knock sticks, but with a spring gentler flat bed.

Here is a further description of the dressing of the bird skins using the example of the smaller Grebes from 1895:

- Dressing up the grebes is pretty easy. They are soaked like lambskins , then washed, rinsed well and meat, the latter always from the center to the side; Then they come still wet into the completely pure lauter tun , the fourth part of which is filled with very dry, clean sawdust of soft wood and the Grebes are now left in there until all the moisture from the skins has passed into the chips: they are When the shavings are damp and no longer absorb moisture from the skins, they must be renewed. You can then apply wet powder to the feathers and, after it has dried, cleanse the grebes again in dry shavings of 'hard' wood.

All bird skins were in their natural state, undyed, processed, at most slightly blinded (provided with a paint). A specialist book for dyers in 1863 describes the bleaching of non-pure white swans and similar skins by burning powdered sulfur (sulfur, white bleaching).

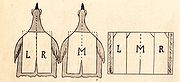

The swan skins, on which only the down feathers had been left, were mostly used for trimmings. To do this, they were cut into narrow strips. The goose and swan fur is flatter towards the neck, it is strong and full in the middle and too smoky and fluttering towards the trunk. Therefore, the trim strips were sorted according to the smoke and the amount of fluff (Fig. 4). Any irregularities that occurred were evened out with scissors after sewing them together. Pre-made swan brews were later also available in stores.

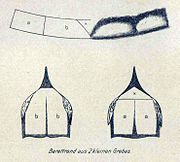

Bird skins are regularly cut open in the back. When processing, for example, grebe's skin, it is important to ensure that the middle of the skin has a uniform width. In order to get an even finish, perhaps with a muff, one usually put a short-haired, color-harmonizing fur on the fur sides. The strange soft fur could also be fed to the fabric much better than the stiff grebe skin. The area for larger sleeves was widened by cutting a skin in half and attaching the middle of the skin to the middle skin (Fig. 3).

When making collars from Grebes (Fig. 1), the width of the collar is tied to the size of the fur. The wild feather end of the fur was cut diagonally inwards, as were the bare sides. These were replaced by sealbisam or other fur. The middle of the fur was pulled in a little with double thread before stretching, or small wedges were cut out in order to round the neck. In the outer edge of the collar, inconspicuous wedges made of flat white rabbit fur could be used, which were covered by the feathers. In the middle of the back of the collar, where the feathers meet, a 1 ½ centimeter wide rabbit strip was inserted to prevent the formation of an ugly comb.

Edge strips for berets (Fig. 2) were either worked around in the direction of the feather, always strips for two berets, one from the left and one from the right halves of the hide, the middle of the belly was always taken into the edge, i.e. towards the face. Or you let the spring direction run backwards, diverging at the front, even for wider hat trimmings.

The usual seams on hairy furs, especially for changing shape, should be avoided if possible on bird skins.

Feather dressers liked to buy the waste from grebe processing when the fashion was up, as were the many damaged hides that were found in large lots and that had already been sorted out at the dealer's.

- Bird skin processing techniques at the end of the 19th century

Numbers and facts

- In 1776 , the purchase value of 6 swan skins from the Hudson's Bay Company was equal to that of a beaver skin .

- In 1810 , a Northwest Company yield report listed: 1833 swan skins, 98,523 beaver skins, 2,645 otter skins, and 554 marten skins .

- A random list of shipments made by this company to London included: 30 swan skins from the Western Outfit in 1830 , 8 from the Upper Missouri Outfit in 1838 , 68 from the Northern Outfit in 1840 .

- The Hudson's Bay Company was able to deliver significantly more, a circular published in 1846 by the London fur trading house CM Lampson listed the company's annual import: 2576 hides in 1844 , 2453 pieces in 1845 and 1922 in 1846 .

- In 1910 the wholesale price for a small or medium-sized, pre - prepared Grebeskin was about 30 pfennigs, for a large Russian one to 1.50 marks and 2 marks for Turkish and Californian ones.

- In the days when bird skins were modern, the following quantities came onto the world market: Red-sided Grebes (Russian large) 200,000 to 300,000 pieces, medium 50,000 pieces, small about 100,000 pieces, Turkish 30,000 pieces and Californian 5000 pieces.

- In 1925 a prepared swan skin cost 10 to 12 marks, a goose skin around 5 marks. Around 60,000 goose skins and 10,000 swan skins were sold annually. They were bundled by the dozen and traded that way.

- The wholesale price of a blanket made of the skins of the king eider , which was bordered on the edge with the neck fur drawn in light green and white, fluctuated between 60 and 100 marks.

- For the very little traded emufels, 10 to 20 marks each was paid.

- Feather and bird skin costumes

Maori (1885)

California, Indians with condor wings ( Kunstkammer , Saint Petersburg)

"Urzel", mask with bird skin and hare skin ( Sachsenheim , Ludwigsburg district, 2015)

See also

supporting documents

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Fritz Schmidt : The book of the fur animals and fur . FC Mayer Verlag, Munich 1970, pp. 388-391.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Paul Larisch , Paris: Das Kürschner-Handwerk (Larisch and Schmid) , III. Part, second improved edition, self-published, Berlin. Without year (probably 1910, reprinted 1924. First edition Paris 1902), pp. 83–84 (in the first edition pp. 67–68).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Friedrich Kühlhorn: The use of the feather and the bird's hide among primitive peoples . Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig 1937, p. 8-55 .

- ↑ Valentina Gorbatcheva, Marina Federova: Die Kunst Sibiriens ( Art in Siberia ). Parkstone Press International, New York 2008, pp. 138-139. ISBN 978-1-84484-564-4 . → Illustration in the English edition

- ↑ Adam Olearius (1603–1671): Three Eskimos visiting Schleswig In: Sleswigland , 1985, edition 5.

- ↑ a b Dr. Eva Nienholdt: Men's furs in folk costumes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVII / New Series 1966 No. 3, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 131-133. Primary source for the pelts of the Samoyed: Description of all nations of the Russian Empire , 1776.

- ^ Fridtjof Nansen: Eskimo Life . Cambridge University Press, June 27, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e Jill Oakes, Rick Riewe: The art of the Inuit women. Proud boots, treasures made of fur . Frederking & Thaler, Munich, pp. 30, 48, 72, 73. ISBN 3-89405-352-6

- ↑ Valeria Alia: Arts and Crafts in the Arctic . In: Wolfgang R. Weber: Canada north of the 60th parallel . Alouette Verlag, Oststeinbek 1991, ISBN 3-924324-06-9 , p. 102.

- ↑ Georg Ebert: The development of the white tannery . U. Deichertsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1913, p. 14. According to: Biart: Les Aztèkes Histoire, Moeurs, Costumes par Lucien Biart . Bibliotheque Ethnologique, Paris 1885, p. 212.

- ↑ The American Museum of Natural History - an introduction (fig.). Last accessed September 25, 2015.

- ^ The American Museum of Natural History: An introduction . 1972. Last accessed September 25, 2015.

- ↑ Der Kirschner , in: JS Halle: Werkstätten der Gegenwart Künste , Berlin 1762, see p. 313 , p. 308 , p. 321 .

- ↑ a b c Alexander Tuma jun .: The furrier's practice . Julius Springer, Vienna 1928, p. 148, 149, 357 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Heinrich Hanicke: Manual for Kürschner , Verlag von Alexander Duncker, Leipzig, 1895, pp. 40–43.

- ^ Marie Louise Steinbauer, Rudolf Kinzel: Marie Louise Pelze . Steinbock Verlag, Hanover 1973, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ http://www.marlenedietrich-filme.de:/ Sabina Lietzmann: Reunion with Marlene . From Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of May 5, 1960. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/ Marlene Dietrich in Schwanenpelz, live in Stockholm. Retrieved Mar 26, 2015.

- ^ Information from Barbara Schröter, Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek (SDK) Museum for Film and Television, Berlin-Marienfelde branch of April 18, 2017.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 2nd improved edition. Publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925, p. 855-859 .

- ↑ Erich Rutschke: The wild ducks of Europe - biology, ecology, behavior , Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden 1988, p. 279. ISBN 3-89104-449-6

- ↑ a b c d e f g K. HC Jordan: Livestock and animal raw materials . Academic publishing house Geest & Portig, Leipzig 1954, pp. 136–137, 140–141.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelzlexikon. XIX. Volume of fur and tobacco products, rabbit hair - Mittelbetrieb , Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1950, Königseiderente p. 60.

- ↑ Friedrich Kramer: From fur animals to fur . 1st edition. Arthur Heber & Co, Berlin 1937, p. 102-103 .

- ^ A b Christian Heinrich Schmidt: The art of furrier . Verlag BF Voigt, Weimar 1844, p. 17.

- ^ A b Arthur Hermsdorf: News . In: Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 4. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 396 ( → table of contents )

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelzlexikon. XVIII. Volume of fur and tobacco products, specialist literature - Kaninfell , Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1949, Grebes p. 76.

- ↑ a b Editor: The goose as an object of the fur trade . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 47, Leipzig, November 20, 1936, p. 2.

- ↑ a b c Paul Cubaeus: The whole of Skinning. 2nd revised edition, A. Hartleben Verlag, Vienna and Leipzig, approx. 1911.

- ^ A b H. Werner: The art of furrier . 1st edition. Bernh. Friedr. Voigt, Leipzig 1914, p. 81 .

- ^ "M." ( Philipp Manes ): On the way. Furrier business in the far north . IV. Episode. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 96, Berlin and Leipzig, August 12, 1929.

- ↑ Editor: Historical fur fashion show in London. Heft 66/67, p. 5, June 11, 1932 and Kormoranmäntel . Issue 74, p. 3, June 29, 1932, In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt.

- ↑ a b c Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition, published by the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, pp. 705–709.

- ^ Hermann Deutsch: The modern skinning. Manual for the furrier, dyer, bleacher, cutter and garment maker . A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna and Leipzig 1930, p. 149

- ↑ The furrier trade . 1st year, No. 3–4, published by Larisch and Schmid, Vienna December 1902, p. 27

- ^ Friedrich Lorenz: Rauchwarenkunde , Verlag Volk und Wissen VEB, Berlin, 1958, p. 139

- ↑ Simon Greger: The furrier art . 4th edition, Bernhard Friedrich Voigt; Weimar 1883, pp. 73-74. (130th volume in the New Scene of the Arts and Crafts series ).

- ↑ The dyeing and finishing of all fur products from animal skins […]. Herm. Schrader's writings, 24th Bdchn., Leipzig 1863.

- ^ Friedrich Justin Bertuch (publisher): Picture book for children , Weimar around 1800

- ↑ Theodor Ruf: The beauty from the glass coffin: Snow White's fairytale and real life . Königshausen & Neumann, 1995, ISBN 3-88479-967-3 , p. 109.

- ^ F. Ilwof: Barter and money surrogates in old and new times . Verlag Leuschner & Lubensky, Graz 1882 (primary source).

- ↑ Inge Prokot, Peter Spielmann: steles objects Photos - a retrospective overview. Inge Prokot . Museum Bochum, Art Collection, April 8, 1978 to May 15, 1978, ISBN 3 8093 0036 5 .

- ↑ Paul Larisch, Josef Schmid: The furrier craft . 1st year, No. 3–4, published by Larisch and Schmid, Vienna December 1902, p. 27

- ^ John Lahs, Georg von Stering-Krugheim: Handbook on wild hides and skins . From the company Allgemeine Land- und Seetransportgesellschaft Hermann Ludwig, Hamburg (ed.), Hamburg 1956, p. 237.

- ↑ Hermann Schrader: The dyeing and finishing of all the fur products of animal skins such as hares, cats, bears, foxes, dogs, rabbits, etc., as beautiful and real as the luxury of the present time demands. Likewise instructions for dyeing in all popular colors, sheep's wool, lamb and angora skins, the so-called swan products, feathers, etc. About finishing and storing all these objects. Instructions for the new, improved display of aniline preparations for the cheapest production of the most beautiful red, purple and blue colors. Based on the latest experiences in England, France and Belgium, everything has been tested by the author through his own practical experiments. CF Amelang's Verlag, Leipzig, 1863, pp. 79-82.

- ^ A b Charles Hanson Jr.: The Swanskin . In: The Museum of the Fur Trade . Vol. 12, No. 4 . Chadron, Nebraska 1976, pp. 1-2 . (English).

- ↑ Jediah Morse: A Complete System of Geography . Boston, 1814 (83 other fur types are listed). Secondary source Charles Hanson Jr.

- ↑ Shipments Vol. 2 (16.410) and Receiving Book Vol. 6 (16.406), American Fur Papers , New York Historical Society, New York. Secondary source Charles Hanson Jr.