Black-throated divers

| Black-throated divers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Black-throated diver ( Gavia arctica ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Gavia arctica | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The black-throated diver ( Gavia arctica ) is a species of bird from the genus of the loons ( Gavia ). The species breeds in the northernmost temperate zone, the tundra and the taiga of Eurasia as well as the extreme west of Alaska and can be regularly observed on the migration, especially in autumn and winter, also in Central Europe. Like other loons, from a distance it looks two-colored. The upper side of the body is dark overall, while the lower side of the body is white.

The species forms a super species with the Pacific diver . In northeastern Siberia and western Alaska there are local sympatric breeding occurrences of these two species. Hybrids occasionally occur in these areas .

There is no reliable information on population trends for the black diver. The world population was roughly estimated by the IUCN in 2002 at 130,000 to 2.0 million individuals. Overall, the species is considered harmless.

description

The black-throated diver is one of the smaller species of the genus Gavia . It is slightly larger than the red-throated diver but noticeably smaller than the yellow-billed common loon and the common loon .

The black diver reaches a body length of 63 to 75 cm and a wingspan of 100 to 122 cm. So far, there is little data on weight; in Russia one male weighed 3310 g at the breeding season, three females weighed between 2040 and 2470 g.

In its splendid plumage , the species can only be confused with the very similar and closely related Pacific diver , whose distribution is limited to North America. The back and the upper wing-coverts are black-gray, the upper back shows dense rows of large white squares on this basis. The head and the back of the neck are gray; the sides of the neck and the sides of the front breast are finely striped in black and white. The chin, throat and the fore neck are sharply defined black, on the throat there is a narrow line of white dots. The chest, abdomen, the rear flanks and the under wing coverts are pure white. The beak is black-gray, the legs are black on the outside and gray on the inside, the webbed feet are gray or flesh-colored. The iris is red.

In the plain dress , the entire top is monochrome black-gray. The skull, back and sides of the neck are gray; the lower sides of the head, chin, throat and front neck are sharply set off white. The gray sides of the neck are often darkly bordered towards the front. The beak is pale gray, the ridge of the beak is dark gray.

The youth dress is very similar to the plain dress, but the feathers on the upper side are more gray-brown and finely lined, so that the upper side appears clearly wavy overall. The iris is brown. The first dune dress is dark brown, the underside of the body of the chicks is somewhat lighter. The belly is gray and an indistinctly whitish ring runs around the eye. The second dune dress is similar, but a bit lighter overall. The belly is whitish.

In simple and youthful clothes, black divers are easy to confuse with other loons, but especially with the slightly smaller red diver . Clear defining characteristics of the black-throated diver in comparison to the red-throated diver are the slightly stronger and straight beak, the mostly straight head, the sides of the neck only about half white in the plain dress, the missing white area in front of the eye and the white flank spot. Overall, the upper side of the body is more monotonous in winter than in red-throated divers.

Activity patterns and locomotion

Black-throated divers are diurnal birds. In their more northern distribution area, they have a 24-hour activity in summer, when it is light there almost all day. They only rest a few times during these 24 hours, mostly around midnight and in the middle of the day. You sleep on the water with your head on your back.

Black divers need a long run-up to take off and usually start against the wind. They only fly up from the water, they cannot fly up from the ground. In flight, the black-throated diver is remotely reminiscent of a large duck. However, due to the legs and feet stretched backwards, it appears longer and shorter-winged. The flight is straight and fast with rapid wing beats. Changes of direction in flight take place in wide arcs, sudden changes of direction are not able to maneuver in the air. They usually fly individually. Mated birds keep their distance from each other and often fly at different heights. During the migration, black-throated divers fly individually or in pairs at an altitude of between 300 and 500 meters.

The black-throated diver comes ashore only very rarely, only when copulating and sometimes when laying feces. Due to his physique, he moves there with great difficulty. He then slides on his stomach, pushing himself forward with his feet. He also uses the wings to help.

In the water, however, the bird is turned. He swims relatively high in the water. However, if he is worried by a danger, he sinks deeper into the water, so that only a narrow strip of the back and neck and the head can be seen. He is a good diver who can stay under the water surface for up to 135 seconds. Usually the dives only last 40 to 50 seconds. It can reach a depth of 45 to 46 meters.

Vocalizations

The district calls are quite variable, most often a long-range , fluting " klooii-ko-klooii-ko-klooii-ko-klooii " can be heard. The rarely uttered flight calls resemble those of geese and can be described as " karr-arr-arr ". Warning sound is a sharp creak.

distribution and habitat

Breeding area

The range of the species includes the northernmost temperate zone, the tundra and the taiga in Europe and Asia . In North America, the species is restricted to the extreme west of Alaska during the breeding season.

In Europe, the species occurs in northern Scotland , in all of Scandinavia, in the northern Baltic states as well as in Russia and then in Asia to the east to the Pacific coast. During the breeding season, it predominantly inhabits larger inland waters, less often small ponds.

Hikes and wintering areas

Black-throated divers are predominantly sea- birds or short-range migrants . Spring and autumn migrations take place in a broad front, so that black-throated divers can be found there on suitable waters. Important areas of the spring migration are the Baltic Sea, Estonia, the Riga Bay , Lithuania, the Curonian Spit , north-eastern Poland, western Ukraine and Moldova. In addition to the areas mentioned, the Dvina and Onega Bay of the White Sea are also of great importance on the autumn migration.

The migration from the breeding area begins at the earliest in mid-July, usually in August or September. In Europe, the species winters mainly in the western Baltic Sea , in the North Sea and on the coast of the Atlantic from Norway to the Biscay , in the northern Mediterranean, on the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea . In Asia, the black-throated diver winters on the Caspi coast of Iran, on the coasts of Japan and Southeast Asia. Occasionally they can also be found on the coasts of Kamchatka and Sakhalin. Occasionally they overwinter in Transcaucasia and Central Asia, where they can be found on the Aral Sea and the lowlands of the Syr Darja. Individual winter guests also hibernate on the American Pacific coast and occasionally reach the Baja California peninsula .

The species is regularly detected in the central European inland during the winter half-year, especially in late autumn and winter from November to February, and more rarely when they migrate home in April and May. Most of the evidence is here on larger lakes. The arrival in the breeding area occurs between April and June.

habitat

The black-throated diver has to rely on large and medium-sized lakes during the breeding season. It finds such suitable lakes in different landscapes of the northern tundra and taiga, but also occurs occasionally in semi-deserts and desert-like foothills such as the Issyk-Kul in the south of its distribution area. In the Altai and Sajan it still breeds at altitudes between 2100 and 2300 meters.

The low tundra with their dense network of lakes of different sizes, but also the forest tundra and forest steppes with many lakes, meet its specific requirements for the habitat. During the migration, the black-throated diver can be found mainly in river valleys, on large lakes and at sea. Not yet sexually mature black-throated divers and non-breeding adult birds spend the summer at sea.

The breeding waters are usually lakes with an extensive open water surface and well-developed reed belt as well as rich underwater vegetation. But they are also able to use low-flow sections of small steppe rivers. The body of water does not need to have suitable prey because it also visits other bodies of water to look for food. Unlike the red-throated diver, however, it prefers breeding waters where it can dive for prey.

nutrition

The food is hunted by diving and consists mainly of small fish, frogs , crustaceans , mollusks and probably also aquatic insects are also captured. The birds are excellent divers who usually hunt at depths between 2 and 6 m, but diving depths of over 40 m have also been proven. The maximum diving time on their forays is 2 minutes. They kill their prey with their beak by squeezing them hard.

The prey fish include herring, gobies, sandeel, capelin , sprat and cod . Freshwater fish include perch, trout, whitefish, roach, bleak, small pike and carp among their prey. They also eat small crustaceans, especially when they are rearing young, when they mostly stay on their breeding lakes to forage. Most of them are flea shrimp. In spring, they also consume aquatic plants and their seeds as a supplement.

Reproduction

Black-throated divers do not reach sexual maturity before the age of three. They are monogamous birds that have a consistent pairing relationship. Therefore, the courtship is very simple, a mutual beak immersion and immersion, before the female climbs up the bank and can be mated. Copulations take place from the first day after arrival.

Breeding area and nest

The area is marked with strong shouts (tu-tui, tui, tui), often in response to the same calls from neighbors. The breeding grounds on large lakes are 50 to 150 hectares in size, the next nest is at a distance of not less than 200 to 300 meters. It is different when the black-throated diver breeds in a dense network of small lakes. Here the nests are often only 50 to 100 meters apart. In general, the black-throated diver is a very loyal bird that returns year after year to breed in the same body of water. The same nest is even used occasionally. In addition to the calls, the area marking includes swimming in pairs with a stretched neck and bowed head or with the front body lifted almost vertically out of the water and splashing swimming and diving.

Both parent birds are involved in building the nest. The female has the greater share. The nesting locations depend on the respective breeding area. On relatively deep and oligotrophic lakes with pronounced and relatively dry banks or on lakes with a wide belt of sedges along the bank, the nests are located on the bank at a distance of 30 to 50 centimeters from the water's edge. Well noticeable paths lead from the bank to the nest. It is the most typical nesting site for black-throated divers. Occasionally, however, they also build their nests in shallow water that is 10 to 60 centimeters deep between blessing and arctophila bulbs. The nest is then a rough truncated cone made of stems, rhizomes and leaves of aquatic plants. The nest base either sits on the bottom or is held in a semi-floating position by the surrounding plant stalks. On large, reed-covered lakes, as are typical of the forest steppe and steppe zone, black-throated divers build their nests on alluvial layers of old, dense and broken reeds in the middle of the deeper water. Real swimming nests are also very rare. When the water level rises, the nest can be moved higher in degrees,

Clutches and young birds

The start of egg-laying depends on the latitude and local spring conditions. Breeding begins in Western Europe, in the middle belt of the European part of Russia and in Kazakhstan from mid-April to early May. In contrast, the beginning of breeding falls in the tundra of northern Europe and in western and eastern Siberia in the third decade of June. In unusually cold weather, the start of egg-laying can even be delayed until mid-July. Black-throated divers raise a maximum of one brood per year. If the clutch is lost at the beginning of the incubation period, you are able to lay another clutch.

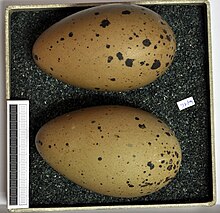

The clutch usually consists of two, only very rarely one or three eggs, which are darkly spotted on an olive-brown to dark-brown background. The breeding season lasts 27 to 30 days. Both partner birds breed, but the female's share of the breeding business is significantly greater than that of the male. The brood begins after the first egg is laid. The chicks hatch asynchronously. They initially remain in the nest for two to three days and are fled there by the parent birds. The chicks are fed by both parents. They argue intensely when they are not fed enough, and often only one boy survives. They are able to feed themselves by around five weeks of age and fledged by around two months.

Negative influences

Skuas and large gulls such as herring gulls and ice gulls plunder the clutches when they are left alone by the parent birds. This occurs especially when the black-throated divers are troubled by humans and they then leave their nest. It is considered to be the main reason why black-throated divers no longer or less often occur in more densely populated regions. The arctic fox also has a special influence . In years when lemmings and voles are rare, they destroy between 90 and 100 percent of the black-throated diving clutch in some regions.

Black diver and human

In some regions of the distribution area, the local population collects loon eggs for consumption. However, this is not considered to be a threat to the company's existence. More problematic is that large numbers of adult birds perish in set up fishing nets. At sea, the pollution of the water by oil poses a particular threat to black-throated divers. In some regions black-throated divers are also considered wild fowl, but are not specifically hunted, but are usually rather random prey.

The previous processing in the fashion industry has been completely discontinued. In the past it was quite common to use the bellows of black divers for women's hats and light collars.

supporting documents

literature

- Hans-Günther Bauer, Einhard Bezzel and Wolfgang Fiedler (eds.): The compendium of birds in Central Europe: Everything about biology, endangerment and protection. Volume 1: Nonpasseriformes - non-sparrow birds. Aula-Verlag Wiebelsheim, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89104-647-2 .

- Einhard Bezzel: Compendium of the birds of Central Europe. Nonpasseriformes - non-singing birds . Aula, Wiesbaden, 1985: pp. 13-17. ISBN 3-89104-424-0 :

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim , Kurt M. Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Volume 1: Gaviiformes - Phoenicopteriformes. Aula, Wiesbaden, 2nd ed. 1987, ISBN 3-923527-00-4 , pp. 74-84.

- VD Il'ičev, VE Flint (ed.): Handbook of birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden 1985, ISBN 3-89104-414-3

- Lars Svensson, Peter J. Grant, Killian Mullarney, Dan Zetterström: The new cosmos bird guide . Kosmos, Stuttgart; 1999: p. 13. ISBN 3-440-07720-9

- Sjölander, Sverre. Reproductive behavior of the Black-throated Diver Gavia arctica. Ornis Scand. 9: 51-65. 1978.

Web links

- Gavia arctica in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on 4 December of 2008.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Gavia arctica in the Internet Bird Collection

- xeno-canto: Sound recordings - Black-throated Loon ( Gavia arctica )

- Black diving feathers

Single receipts

- ↑ Bauer et al., P. 197

- ↑ VD Il'ičev, VE Flint (ed.): Handbook of the birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: Erforschungsgeschichte, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes , 1985, p. 216

- ↑ a b c d Il'ičev, Flint (ed.): Handbook of the birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes , 1985, p. 223

- ↑ a b V. D. Il'ičev, VE Flint (ed.): Handbook of the birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes , 1985, p. 215

- ↑ a b c d Il'ičev & Flint (eds.): Handbook of the birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: Erforschungsgeschichte, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes , 1985, p. 219

- ^ Lars Svensson, Peter J. Grant, Killian Mullarney, Dan Zetterström: Der neue Kosmos Vogelführer . Kosmos, Stuttgart; 1999: p. 13. ISBN 3-440-07720-9

- ^ A b Jonathan Alderfer (Ed.): Complete Birds of North America , National Geographic, Washington DC 2006, ISBN 0-7922-4175-4 , pp. 60 and 61

- ↑ a b V. D. Il'ičev, VE Flint (ed.): Handbook of the birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of research, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes , 1985, p. 218

- ^ Birds on the sea and coast . In: Birds of our region . A6 020 06-07 (2). Atlas Publishing House.

- ↑ a b V. D. Il'ičev, VE Flint (ed.): Handbook of the birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes , 1985, p. 220

- ↑ VD Il'ičev, VE Flint (ed.): Handbook of the birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: Erforschungsgeschichte, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes , 1985, p. 220 and p. 222

- ↑ Collin Harrison, Peter Castell: Young birds, eggs and nests of birds in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. 2nd Edition. Aula, Wiebelsheim 2004, ISBN 3-89104-685-5 . P. 31

- ↑ VD Il'ičev, VE Flint (ed.): Handbook of the birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: Erforschungsgeschichte, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes , 1985, p. 224