Birds of paradise

| Birds of paradise | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Little bird of paradise |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Paradisaeidae | ||||||||||||

| Vigors , 1825 |

The Paradiesvögel (Paradisaeidae) are a bird family which to order the Sperlingsvögel (Passeriformes), subordination songbirds part (Passeres). They weigh between 60 and 440 grams and, without the extended central control springs, have a body length between 16 and 43 centimeters. In a number of species, parts of the plumage of the males have a noticeably different feather structure and are greatly elongated. This is especially true for parts of the tail plumage. Including these tail feathers, which are often wire-like, birds of paradise can reach a body length of over one meter. The sexual dimorphism is very pronounced, especially for those species that do not live in a monogamous couple relationship. The males have sometimes very colorful plumage, while muted brownish plumage tones dominate the females. Birds of Paradise are long-lived birds. In the males, the adult plumage shows up only after several years. In captivity, they can live up to 33 years of age.

New Guinea is the main distribution area of this family. New Guinea owes the nickname "Island of the Birds of Paradise" to this fact. They also occur in the extreme north of the rainforests of Australia , some islands of the Moluccas and archipelagos off the coast of New Guinea. Many species of the birds of paradise live in inaccessible mountain ranges and have so far been little researched. Some species were not photographed and filmed for the first time until the 21st century. It is also believed that there are still species that have not yet been scientifically described.

Most bird of paradise species are classified as not endangered. Blue Bird of Paradise , broad tail Paradieshopf and lavender Bird of Paradise , a Inselendemit whose distribution on the islands Normanby and Fergusson is limited in the southeast of New Guinea, (be as vulnerable vulnerable ) classified.

Appearance

The birds of paradise divide into two subfamilies with very different appearances. In both subfamilies, the female is smaller than the male. Measured in terms of wing length, this size difference is most pronounced in the magnificent bird of paradise , in which the average wing length is only 81% of the wing length of the male. All species with sexual dimorphism are polygynous , but there is also polygamy in species in which there is no sexual dimorphism. What all species have in common is that they have ten arm swings and 12 control springs . Most species also have small, forward-facing feathers at the base of the beak that cover the nostrils.

Subfamily Phonygamminae

The species of the subfamily Phonygamminae differ from the other birds of paradise mainly by their crow-like appearance, which is also reflected in the frequent use of "crow" in the German trivial names. Their plumage is predominantly blue-black and with an intense iridescent sheen. They reach a body length between 34 and 43 centimeters and are the heaviest species among the birds of paradise with the up to 440 grams heavy crow of paradise. The females of the species in this subfamily are usually slightly smaller than the males. The sexual dimorphism is only slightly pronounced in them - in some species only the plumage of the females shines in a slightly different tone.

Subfamily Actual birds of paradise

In the subfamily of the actual birds of paradise , the size difference is very pronounced. The smallest species is the king's bird of paradise, in which the adult females occasionally weigh only 38 grams and the males, without the extended middle pair of control feathers, have a body length of 16 centimeters. The broad-tailed paradise hop , on the other hand, with its greatly elongated tail plumage, its comparatively long neck and beak reaches a body length of more than one meter. However, they weigh an average of only 227 grams, significantly less than the crowded paradise crow .

The sexual dimorphism is often very pronounced in this subfamily. The males are usually much more colorful than the females. The thread hop is the species with the most noticeable sexual dimorphism. Males and females share almost no feature of the plumage.

The males of this subfamily either have strongly contrasting plumage or are velvety black with individual, strongly iridescent body parts. For example, the great bird of paradise ( Paradisaea apoda ) has noticeably long, red tail feathers in addition to the yellow dorsal plumage and the bright green throat area . The male of the smaller sickle- tail bird of paradise ( Cicinnurus magnificus ) is characterized above all by the eponymous sickle tail made of two long feathers. The body of this animal is a mosaic of bright green, blue, yellow and red. The females of both species are rather inconspicuously drawn brown-yellow. The birds of paradise have six very elongated ornamental feathers on their heads, which taper off in a spatula-shaped manner, as well as a bronze-colored, shiny, scale-like breast plumage. This shiny breast plumage is also found in the pennant bearer , the only representative of the genus Pteridophora . He wears a greatly elongated headdress feather on each side of his head, which, with a length of up to 50 centimeters, is twice as long as his body length. Detection and eponymous feature of this bird of paradise are the pennant -like structures in these head feathers . About 40 to 50 of these leaflets with a light blue upper and red-brown underside sit on one side and regularly on the spring shaft.

voice

Most of the sounds that birds of paradise make are harsh and croaking. They have been repeatedly compared to the sounds of ravens and crows . There are, however, a number of exceptions: This ranges from the high, low calls of some manukodes , the staccato-like sounds of the narrow-tailed paradise hop , reminiscent of machine gun fire, to the humming sounds of the blue paradise bird . With the exception of a few monogamous species, only calls from the male can be heard.

The Manukoden species and the Schall Manucodia have an elongated trachea in the males as an anatomical feature. It lies in loops over the chest muscles and directly under the skin of the chest. Frith and Beehler suspect that this elongated windpipe, which is very unusual for songbirds, has the function of lowering the pitch of the males' calls and thus ensuring that they can be heard from afar. This feature is absent in the Lycocorax species, but the skull structure is similar to that of the Manukodes.

Distribution area and habitat

Birds of paradise are limited in their distribution to Australasia . The majority of the species occurs in New Guinea and islands immediately adjacent to the coasts of New Guinea. A few species, such as the lavender bird of paradise, are island endemics. There are only four species of avifauna in Australia : In addition to the Schall Manucodia, there are Victoria , Magnificent and Shield Bird of Paradise . They belong to the birds of paradise whose way of life has been well researched.

The ranges of the individual species are often small and sometimes limited to a single mountain range in New Guinea. In contrast to some other passerine birds, where the range extends over several continents, the range of the Schall-Manucodia as the species with the largest range among the birds of paradise only extends from the Vogelkop in the extreme west of New Guinea to the D'Entrecasteaux Islands in the east and the Australian Cape York Peninsula south of New Guinea. The distribution area of the long-tailed paradigalla , however, is limited to the Arfak Mountains in the northeast of the New Guinean Vogelkop peninsula. There is another Paradigalla population in the Fakfak Mountains on the Fakfak Peninsula at the western southern end of the island of New Guinea, which was previously assigned to this species. In the meantime, however, it has been assumed that this population is a species of the genus Paradigalla that has not yet been scientifically described and is limited to this mountain range .

In contrast to most families of passerine birds, the species do not occur in a wide range of habitats , but are rather limited in their habitat to rainforests and similar dense vegetation types. This also applies to the four species found in Australia, where the predominant habitats are light forest areas, savannas and deserts.

Courtship

The courtship behavior for some of the birds of paradise has not yet been described or has only been described superficially. The description of courtship is also made more difficult by the fact that males initially wear the plumage of an adult female. In the case of “females” that appear at a courtship site, it can always be a not yet sexually mature male. It can take a long time before the typical plumage of an adult male appears. A bird captured in the plumage of an adult female sickle-tailed bird of paradise in August 1969 did not begin to show the plumage of an adult male until September 1975. So he was at least six years old at the time. It is just as long for the males of the red birds of paradise. A male of the narrow-tailed paradise hop , which was handed over to the Baiyer River Sanctuary , Papua New Guinea on September 13, 1978 , and which initially still showed the plumage of a female, let the jackhammer-like call typical of the males be heard for the first time in July 1982. A year later it began to show the first feathers from an adult male. This individual only wore the full plumage of a male in May 1985. This leads to the conclusion that the males of this species only show the plumage of adult males at the age of seven to eight years.

As different as the appearance of the animals is their courtship behavior. With the male birds of gods, courtship for females also means a competition. Here several males court together on a courtship area that is in the catchment area of several females. They lure their "admirers" with loud calls to the courtship area, where they present their decorative feathers by throwing them over their bodies. The females choose one of the males and allow themselves to be mated by it, then leave the dance floor and look after the offspring alone. A particularly dominant male can mate several females, while other, less magnificent males have no chance.

The sickle-tailed bird of paradise also offers an impressive courtship dance, mainly raising its feathers into a high collar and thus dancing on vertical trunks. However, he mates alone in the territory of a female. If the mating is successful, however, he does not stay with the female either, but looks for a new courtship area and new partners. What both species have in common is that a successful male can mate with several female partners. This mating strategy is known as polygyny (polygamy).

Again, the Schall-Manucodia, together with some other species, represents a representative of a completely different strategy. Here the male does not impress the female with a conspicuous courtship behavior. Once a couple has been found, they stay together and raise the offspring together. So these are monogamous animals.

food

Inevitably, the question arises why the individual species behave so differently. The answer can probably be found in the animals' different nutritional needs. The Schall Manucodia feeds primarily on figs , which are difficult to find and quite poor in nutrients. Both parents are required to raise the brood and provide it with food. The sickle-tailed bird of paradise and also the bird of gods have switched their diet to more nutritious fruits such as nutmeg , and they also supplement their diet with insects , which are relatively easy to find. This is how a female manages to care for her offspring on her own.

Life expectancy

Since many species of birds of paradise occur in remote regions, comparatively few individuals have so far been ringed and then found again. In principle, however, it can be assumed that birds of paradise live comparatively old. This is also indicated by the few re-finds of ringed birds:

- A fully grown male of the Victoria Bird of Paradise ringed in Yungaburra National Park in October 1988 was recaptured in the same location almost nine years later. Another male who was at least 3 years and 3 months old when he was ringed was killed by a domestic cat 15 years later.

- A single, fully grown male of the Blue-necked Bird of Paradise that was ringed on October 29, 1978, was recaptured from the same location on December 7, 1986. The life expectancy of this species is therefore likely to be well over nine years.

- An adult male of the Carola Bird of Paradise was delivered to the Honolulu Zoo in 1954 and lived there until November 1969. He should therefore have been at least 15 years old.

- The age record for a male Raggi bird of paradise living in the wild is held by a bird ringed on Mount Missim on September 1, 1980. At that time he still wore the female-like plumage typical of subadult males. It was caught again in July 1997, when it was wearing the adult plumage of the males. He was at least 16 years and 10 months old at the time.

- A hand-reared male Raggi Bird of Paradise lived in the Baiyer River Sanctuary for 25 years. Another male, at least 33 years old, is reported to have successfully mated at this age.

Systematics

There are a total of 43 species of birds of paradise in 16 genera ; Supporters of the phylogenetic species concept even split them into 90 different species. No new species have been described since 1992. The family is divided into two subfamilies. The following species are currently recognized:

Subfamily True Birds of Paradise (Paradisaeinae) Vigors , 1825

-

Paradise star ( Astrapia ) - 5 types

- Narrow- tailed paradise magpie ( Astrapia mayeri )

- Black-throated paradise magpie (

- Rothschild Paradise Magpie ( Astrapia rothschildii )

- Splendid paradise magpie ( Astrapia splendidissima )

- Stephanie's paradise magpie ( Astrapia stephaniae )

- King's Bird of Paradise ( Cicinnurus regius )

- Bare-headed bird of paradise ( Diphyllodes respublica )

- Sickle-tailed bird of paradise ( Diphyllodes magnificus )

- Yellow-tailed paradise hop ( Drepanornis albertisi )

- Brown- tailed paradise hop ( Drepanornis bruijnii )

- Broad-tailed paradise hop ( Epimachus fastosus )

- Narrow-tailed paradise hop ( Epimachus meyeri )

- Collar bird of paradise ( Lophorina superba )

- Papua bird of paradise ( Lophorina intercedens )

- Short-tailed Paradigalla ( Paradigalla brevicauda )

- Long-tailed Paradigalla ( Paradigalla carunculata )

- Great bird of paradise ( Paradisaea apoda )

- Ornamental bird of paradise ( Paradisaea decora )

- Emperor Bird of Paradise ( Paradisaea guilielmi )

- Little bird of paradise ( Paradisaea minor )

- Raggi Bird of Paradise ( Paradisaea raggiana )

- Red bird of paradise ( Paradisaea rubra )

- Blue Bird of Paradise ( Paradisaea rudolphi )

- Berlepschparadiesvogel ( Parotia berlepschi )

- Carola ray of paradise (

- The Helena bird of paradise , which has long been classified as an independent species, is now a subspecies of the blue-naped bird of paradise and is accordingly listed as Parotia lawesii helenae .

-

Pteridophora - 1 type

- Pennant Bearer ( Pteridophora alberti )

-

Ripe birds ( Ptiloris ) - 3 species

- Magnificent bird of paradise ( Ptiloris magnificus )

- Shield bird of paradise ( Ptiloris paradiseus )

- Victoria Bird of Paradise ( Ptiloris victoriae )

-

Seleucidis - 1 kind

- Fadenhopf ( Seleucidis melanoleucus )

-

Semioptera - 1 species

- Ribbed Bird of Paradise ( Semioptera wallacii )

Subfamily Phonygamminae G.R. Gray , 1846

-

Lycocorax - 2 types

- Crow bird of paradise ( Lycocorax pyrrhopterus )

- Obi paradise crow ( Lycocorax obiensis )

-

Manukodes ( Manucodia ) - 4 species

- Bright Paradise Crow ( Manucodia ater )

- Green Paradise Crow ( Manucodia chalybatus )

- Ruffle Paradise Crow ( Manucodia comrii )

- Jobi Paradise Crow ( Manucodia jobiensis )

-

Phonygammus - 1 type

- Sonic Manucodia ( Phonygammus keraudrenii )

Hybridization within the family

History of science

The tendency of birds of paradise to cross with other species in their family was already described by Anton Reichenow at the beginning of the 20th century and thus almost earlier than for any other bird family. As early as 1901, Reichenow considered it probable that the species, which he originally described as Janthothorax mirabilis as a new species, was in fact a cross between the two bird of paradise species thread hop and a species from the genus of the actual birds of paradise. This idea was initially not accepted by the professional world. It was not until 1930 that the German ornithologist Erwin Stresemann published two articles in which he took the view that no fewer than 17 of the birds of paradise previously described as a species were of hybrid origin. This view initially found support from the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr , but it took several decades to establish itself. Today, only very few of the potential hybrids originally identified by Stresemann are still being discussed as to whether an independent species might exist.

Examples of hybrids

The type specimens in museum holdings that are now considered hybrids are predominantly males. On the one hand, this is due to the fact that the indigenous ethnic groups in New Guinea mainly hunted the males equipped with conspicuous decorative feathers and brought them to the trade as hide or bird skin . In the males, deviating characteristics are also more noticeable than in the rather inconspicuous colored females.

The species in which hybrids are particularly common include the narrow-tailed paradise magpie , which crosses with the species Prachtieselster and Stephanie-Paradieselster belonging to the same genus and also the narrow-tailed paradise hop. For the sickle-tailed bird of paradise , hybrids with the king's bird of paradise , the collar bird of paradise and the little bird of paradise have been described.

Birds of Paradise and Man

History of science

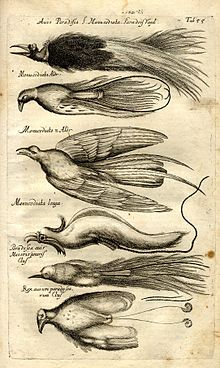

The male plumage of some species is so bizarre and in some cases so unlike the feathers of other bird species that at the beginning of the history of science some ornithologists were convinced that the bellows sent to Europe were elaborate forgeries. The first bellows that reached Europe came from the Spanish explorer Juan Sebastián Elcano from the first circumnavigation of the world . He had received it in November 1521 on the Tidore Islands . A scribe at the court of Charles V described one of these hides in a letter to the Archbishop of Salzburg . In this letter, published in Cologne in 1523, the writer also noted that these birds of paradise were missing feet and legs and that they never landed, but flew until they fell to earth, dying. The other bird of paradise bellows that came to Europe in the course of the 16th century seemed to confirm this: In New Guinea, they were bellows prepared in the traditional way, from which their feet and legs had been removed. It was not until the beginning of the 17th century that bellows that still had legs and feet reached Europe.

The first monograph on birds of paradise was published in 1802 by the French Louis Pierre Vieillot and Jean Baptiste Audebert . Only 11 species were described. This first scientific work, which dealt exclusively with birds of paradise, was followed by others by the ornithologists René Primevère Lesson , John Gould (1804–1881) and Richard Bowdler Sharpe (1847–1909), Daniel Giraud Elliot (1835–1915), Tom Iredale ( 1880–1972) and Ernest Thomas Gilliard (1912–1965).

Bellows and feathers in western hat fashion

In Europe and North America, between the last quarter of the 19th century and around 1920, women's hats were preferably decorated with bird feathers, but also with bird fur. Under fur in the bird is fur industry the withdrawn, feathered skin of birds understood, which is preserved by tanning. Wings, heads and complete bird hides were used. The skins of birds of paradise, including the actual birds of paradise with their conspicuous, elongated flank feathers, were particularly popular, as is shown by numerous photos showing the hunters with the skins they shot. In Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land , the north-eastern part of New Guinea, which belonged to the German colonial empire until 1919 , high license fees had to be paid for the right to hunt because of the high prices that could be achieved with the bird of paradise hide. The wholesale price for such a bellows was about 130 marks on the German market before the First World War. That was half the monthly salary of a police officer. It is estimated that the respective auctions in London, New York and Paris between 1905 and 1920 sold between 30,000 and 80,000 Birds of Paradise every year. As early as 1912, the USA had issued a ban on the import of feathers and feathers from wild birds. In the German empire, the "Bund für Vogelschutz" (forerunner of today's NABU ) campaigned against the fierce resistance of the fashion industry against the "bird murder for fashion purposes". In 1913 the Reichstag dealt with the issue of the protection of birds of paradise and in 1914 the hunt for all bird of paradise species was banned in the colony.

Bellows and springs as a prestige object in Melanesia and Asia

Huli headdress with feathers from magnificent and raggi birds of paradise as well as tail feathers from paradise stars

The feathers and hides of a number of birds of paradise are made into traditional head and body decorations by several indigenous tribes of Melanesia. They play a special role with the peoples of New Guinea and here especially with the peoples who live in the highlands of Papua New Guinea.

With few exceptions, bellows and feathers as jewelry are worn exclusively by men. They are part of traditional clothing that is worn during armed conflicts, but also serve as decoration for ceremonial robes. As a symbol of status and prosperity, bellows and feathers have been a commodity for several thousand years. The trade is not limited to the range of the birds of paradise. Long-distance trade with them has existed with the southeastern mainland of Asia, the Philippines and the eastern islands of Indonesia for at least 2000 years. The flank feathers of the Great Bird of Paradise, for example, have adorned the headgear of high-ranking members of the Nepalese royal court for centuries. They were worn by the king, the prime minister and generals on special ceremonial occasions. The Nepalese crown uses particularly long flank feathers, which emerge from a jeweled setting like a horse's tail.

The hunt is concentrated exclusively on the males because the females lack these decorative feathers. Before rifles were widespread in New Guinea, hunting was carried out exclusively with bows and arrows, limesticks and traps. Hunters often used the traditional leks - the courtship grounds where several males gathered - to hunt the males with their ornamental plumage. When hunting, blunt arrows were preferred so as not to damage the plumage. A law in Papua New Guinea even only allows traditional hunting with a bow and arrow or slingshot. Traditional hunting does not reduce the population of the polygonal species: as a rule, the oldest males are hunted, which have the most pronounced ornamental plumage. Wherever they are missing, the females mate with the younger males. For example, despite the generations of hunting for the Little Bird of Paradise, its population is stable, and in some regions the species is even very common - the Little Bird of Paradise on the island of Yapen is one of the most common birds in the lowlands, in the foothills as well as in mountain forests. There are, however, exceptions to this rule: In the 1970s, it was found that the population of Great Birds of Paradise in the regions where rifles were introduced significantly decreased. Where this was not yet the case, the numbers remained comparatively high. The individuals of this species were also noticeably tamer there.

The example of the blue bird of paradise, which is classified as endangered and only occurs in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, shows, however, that the combination of several factors, even with polygonal species, can mean that they cannot compensate for the population loss due to hunting.

- Both bellows and individual feathers are occasionally sold to tourists, although exporting them out of the country is illegal.

- The occasions when ceremonial robes are worn have increased. Both Independence Day and Christmas are now occasions for wearing these feather-adorned clothes or the feather-adorned headdress.

- Due to the increasing population density, there are more children who kill females on the nest with slings.

- There is no executive to ensure the enforcement of laws and regulations on hunting. Furthermore, these regulations are sometimes not understood by the indigenous peoples or they are incomprehensible to them, so that they have no influence on hunting and trading practices.

Trivia

Dedication names

For several decades, predominantly members of European royal houses were honored with the award of the specific epithet :

- The German name and the epithet of the Stephanie-Paradieselster were given in honor of Stephanie of Belgium at the time of the first scientific description of the Crown Princess of Austria-Hungary . The specific epithet rudolphi of the blue paradise bird honors her husband, the Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary .

- The German name and the specific epithet of the Carola bird of paradise honor Carola von Wasa-Holstein-Gottorp , the last queen of Saxony. In the same year, AB Meyer honored her husband Albert von Sachsen , the additional species alberti of the scientific name of the pennant bearer reminds of the Saxon king.

- The specific epithet of the Kaiser bird of paradise ( Paradiesaea gulielmi ) is reminiscent of the German Emperor Wilhelm II. Gulielmili is the medieval Latin form of Wilhelm.

- The Victoria Bird of Paradise is named after Queen Victoria .

- The name of the Helena bird of paradise ( Parotia lawesi helenae ), a subspecies of the blue-naped bird of paradise, honors Helena of Great Britain and Ireland , the third daughter of Queen Victoria .

However, a few more birds of paradise are named after collectors or personalities in connection with the European first description:

- The specific epithet of the narrow-tailed paradise hop ( Epimachus meyeri ) the German natural scientist Adolf Bernhard Meyer .

- The specific epithet of the yellow-tailed sickle hop Drepanornis albertisi honors the Italian explorer Luigi Maria d'Albertis , who at his first encounter with this species immediately realized that this was a new genus and a species of the family of birds of paradise. D'Albertis was only a little earlier than Adolf Bernhard Meyer with his discovery on Mount Arfak in 1872. Meyer also encountered this species in the same year.

- The specific epithet bruijnii of the Braunschwanz-Paradieshopf honors the Dutch plumassier and natural produce dealer Anton August Bruijn . As a trader, he supported the natural scientist Alfred Russel Wallace on his trip to the Moluccas . The type specimen, on which the first scientific description is based, was collected by the hunter L. Laglaize, who collected in New Guinea on behalf of Bruijn. Bruijn had already become aware of the existence of this species four years earlier.

Others

- The bright paradise crow is the first bird of paradise that a European, René-Primevère Lesson, observed in the wild.

- The Italian explorer Luigi Maria d'Albertis reported in 1880 that he had eaten the meat of four Arfak radiation paradise birds. This is considered remarkable because the flesh of the birds of paradise is commonly described as being so unpleasantly bitter that it is considered inedible.

- In the type specimens of the thread hop kept in museums , the flank plumage no longer shows the intense yellow tone. It immediately fades to a whitish tone after the bird dies. The specific epithet melanoleuca indicates this. It means black and white.

- One of the most successful collectors of type specimens of the birds of paradise was the German colonial official, ornithologist and plant collector Carl Hunstein : Hubstein, who worked for the New Guinea company from 1885 until his death in 1888 , collected, among other things, the narrow-tailed sickle-headed head , the Stephanie-Paradieselster , the blue paradise bird and the emperor's bird of paradise .

- Reports of synchronous courtship behavior among males of the imperial bird of paradise were already published in 1924 by the former German colonial officer Hermann Detzner . He described seeing five or six males of this species hanging upside down from a branch. They would have assumed this position by letting themselves slowly tip backwards from the branch. The ornithologist HO Wagner reported in 1938 in the 86th volume of the Journal of Ornithology also of a synchronous courtship with two males of the Emperor Bird of Paradise kept in the Taronga Zoo , Sydney. The observations were strongly doubted by the ornithologists Erwin Stresemann (1924), Ernst Mayr (1931) and Ernest Thomas Gilliard (1969). The ornithologist RDW Draffan, on the other hand, was able to confirm the observation during outdoor observations in 1978.

The origin of the name of the birds of paradise

In his work The Malay Archipelago. The home of the orangutan and the bird of paradise explains to Alfred Russel Wallace the origin of the name and the history of the discovery of the birds of paradise:

- Since many of my trips had been made for the special purpose of obtaining specimens of birds of paradise and learning of their habits and distribution, and since I am the only Englishman (as far as I know) who have seen these wonderful birds in their native forests and has received many of them, I intend here to give the result of my observations and investigations in connection with this.

- When the first Europeans reached the Moluccas in search of cloves and nutmegs, rare and valuable specimens at the time, they were presented with dried bird skins, which were so strange and beautiful that they aroused the admiration of even those seafarers who were hunting for wealth. The Malay traders named them "Manuk dewata" or "Birds of the Gods"; and the Portuguese, seeing that they had neither feet nor wings, and being unable to learn anything authentic about them, called them "Passaros de Sol" or "Sunbirds," while the learned Dutch called them in Latin wrote that they were called "Avis paradiseus" or "Birds of Paradise". John von Linschoten gave them this name in 1598 and he told us that nobody had seen the birds alive, because they live in the air, always turn towards the sun and never settle on the earth before they die; they have neither feet nor wings, as can be seen, he adds, in the birds which were brought to India and sometimes to Holland, but as they were very expensive at the time, they were seldom seen in Europe . More than a hundred years later, Mr. William Funnel, who accompanied Dampier and wrote an account of the trip, saw several copies on Amboina and was told that they came to Banda to eat nutmegs, which made them intoxicated and made them fall unconscious whereupon they would be killed by ants. Until 1760, when Linnaeus named the largest species Paradisea apoda (footless bird of paradise), no perfect specimen had been seen in Europe and absolutely nothing was known about it, and even now, a hundred years later, most books state that it was wander annually to Ternate, Banda, and Amboina, while the fact is that they are as unknown on these islands in their wild state as they are in England. Linnaeus was also familiar with a small species which he called Paradisea regia (King's Bird of Paradise) and since then nine or ten other species have been discovered, all of which were first described after the bellows kept by savages in New Guinea and were usually more or less imperfect . These are now all known as "Burong mati" or dead birds in the Malay Archipelago, which is to say that the Malay traders never saw them alive.

literature

- Michael Apel, Katrin Glas, Gilla Simon (eds.): Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-00-035219-5 ..

- Brian J. Coates: The Birds of Papua New Guinea. Volume II, Dove Publications, 1990, ISBN 0-9590257-1-5 .

- Clifford B. Frith, Bruce M. Beehler : The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-854853-2 .

- Clifford B. Frith, Dawn W. Frith: Birds of Paradise. Nature, Art, History. Frith & Frith, Malanda, Queensland 2010, ISBN 978-0-646-53298-1 .

- Eugene M McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006, ISBN 0-19-518323-1 .

- R. Bowdler Sharpe: Monograph of the Paradiseidae, or birds of paradise and Ptilonorhynchidae, or bower-birds . Volume I: List of plates . Each plate accompanied by leaf with descriptive letterpress. H. Sotheran & Co., London 1891.

- Monograph of the Paradiseidae, or birds of paradise and Ptilonorhynchidae, or bower-birds . Volume II: List of plates . Each plate accompanied by leaf with descriptive letterpress. H. Sotheran & Co., London 1891.

- E. Thomas Gilliard: Birds of Paradise and Bower Birds. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London 1969, ISBN 0-297-17030-9 .

- PJ Higgins, JM Peter, SJ Cowling: Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 7: Boatbill to Starlings. Part A: Boatbill to Larks . Oxford University Press, Melbou.

- AB Meyer: New birds from Celébes . Notes from the Leyden Museum, Vol. XXIII, Dresden 1903.

- AFR Wollaston: Pygmies and Papuans: the stone age today in Dutch New Guinea. With appendices by WR Ogilvie-Grant, Alfred C. Haddon, Sidney H. Ray, FD Drewitt. John Murray, London 1912.

- Ernst Sutter , Walter Linsenmaier: Birds of Paradise and Hummingbirds. Pictures from the life of tropical birds. Silva picture service, Zurich 1955.

- Erwin Stresemann: The story of the discovery of the birds of paradise. In: Journal of Ornithology. 95 (3-4), 1954, pp. 263-291 - online at Springer

- Alfred Russel Wallace: The Malay Archipelago. Westermann, Braunschweig 1869. (Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-7973-0407-2 )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 5.

- ↑ Handbook of the Birds of the World on the Lavender Bird of Paradise , accessed August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Handbook of the Birds of the World on the Blue Paradise Bird , accessed on August 20, 2017.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 14.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 22.

- ↑ C. Frith, D. Frith: Curl-crested Manucode (Manucodia comrii). In: J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, DA Christie, E. de Juana (Eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2017. ( online , accessed July 9, 2017)

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 9.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 7.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 427.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 305.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 25.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 211.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 206.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 6.

- ↑ Handbook of the Birds of the World on the Green Paradise Crow , accessed on July 9, 2017.

- ↑ Handbook of the Birds of the World on the Langschwanaz Paradigalla , accessed on July 9, 2017.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 392.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 475.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 376.

- ^ PJ Higgins, JM Peter, SJ Cowling: Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. P. 645.

- ↑ Frith and Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 292.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 304.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 469.

- ^ Clifford B. Frith, Bruce M. Beehler: The birds of paradise. (= Bird Families of the World. 6). Oxford University Press, New York 1998, ISBN 0-19-854853-2 .

- ↑ J. Cracraft: The species of the Birds-of-Paradise (Paradisaeidae): apllying the phylogenetic species concept to a complex pattern of diversification. In: Cladistics. 8, 1992, pp. 1-43. doi: 10.1111 / j.1096-0031.1992.tb00049.x

- ↑ Jønsson include: A super matrix phylogeny of passerine birds corvoid (Aves: Corvides). In: Molecular Genetics and Evolution. 94, 2016, pp. 87-94.

- ↑ Handbook of the Birds of the World on Obiparadieskrähe , accessed on July 3, 2017.

- ^ McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. P. 228.

- ^ McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. P. 493.

- ^ McCarthy: Handbook of Avian Hybrids of the World. P. 229.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 4.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 30.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 447.

- ↑ Apel, Michael: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise . Ed .: Museum Mensch und Natur. Munich 2011, p. 75 .

- ↑ Apel, Michael: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise . Ed .: Museum Mensch und Natur. Munich 2011, p. 75 .

- ^ Admin: The Bird Hat: "Murderous Millinery". Retrieved January 23, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Apel, Michael: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise . Ed .: Museum Mensch und Natur. Munich 2011, p. 83 .

- ^ Negotiations of the German Reichstag. Retrieved January 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Apel, Michael: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise . Ed .: Museum Mensch und Natur. Munich 2011, p. 90 .

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 27.

- ↑ a b Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 29.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 146.

- ↑ Apel et al .: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise. P. 57.

- ↑ Apel et al .: Natural and cultural history of the birds of paradise. P. 58.

- ↑ a b c d Paradisornis Rudolphi in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2011. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed October 10, 2017th

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 456.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 307.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 483.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 379.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 387.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 212.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 282.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae. P. 438.

- ^ HO Wagner: Observations on the courtship of the bird of paradise Paradisaea guilielmi , Journal for Ornithology, Volume 86, pp. 550–553.

- ↑ Frith & Beehler: The Birds of Paradise - Paradisaeidae . P. 485.

- ↑ RDW Draffan: Group display of the galleries of Germany Bird-of-paradise Paradisaea guilielmi in the wild. Emu, Volume 78, 1978, pp. 157 - p. 159

- ↑ The Malay Archipelago. The home of the orangutan and the bird of paradise. Travel experiences and studies about the country and its people. Volume 2, Authorized German Edition by Adolf Bernhard Meyer. Westermann, Braunschweig 1869, p. 359 ff.

Web links

- Birds of Paradise: roll call in paradise . By National Geographic author Mel White. - Spiegel online November 24, 2012

- Exhibition on birds of paradise in the Bamberg Natural History Museum

- English-language article on hat fashion with birds of paradise: The Bird hat - Murderous millinery