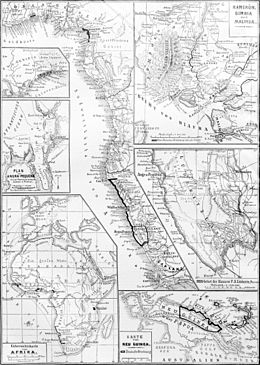

German colonies

The German colonies had been acquired by the German Empire since the 1880s and ceded after the First World War in accordance with the Versailles Treaty of 1919. They were called protected areas by Bismarck because he wanted to protect German trade in them. In 1914, the German colonies were the third largest colonial empire after the British and French . In terms of population, it was fourth after the Dutch colonies . The German protected areas were not part of the Reich territory, but overseas property of the Reich.

Emigrated Germans founded settlements overseas which are sometimes referred to as "German colonies", but which did not exercise any sovereignty rights of their country of origin.

History of German Colonialism

German Federation and German Customs Union

In the states of the German Confederation founded in 1815 and the German Customs Union founded in 1834, calls for German colonies were loud from the private and economic side, particularly from the 1840s. But there were no such efforts on the part of the state. The Hamburg Colonial Society was founded privately in 1839 to buy the Chatham Islands east of New Zealand in order to settle German emigrants there, but Great Britain made older claims to the islands. Hamburg needed the protection of the Royal Navy for its worldwide shipping and therefore renounced the political support of the colonial society. The Association for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas , which was founded in 1842 and wanted to expand the German settlements in Texas into a “New Germany” colony, was somewhat successful , but the annexation of the Republic of Texas by the United States of America in 1845 destroyed this request.

Decisive points for the state's lack of interest in colonies were the limitation of German political thought at the time to the issues in Germany and Europe and the lack of a German sea power that could provide political support for the acquisition of overseas colonies. With the development of the Austrian and Prussian navies from 1848 onwards, such means of power were created.

First attempts at colonial acquisitions at the state level (1857–1862)

In 1857, the Austrian ran frigate Novara of Trieste to an expedition from which the exploration and occupation of the Nicobar Islands in the Indian Ocean included. In 1858 the Novara was called to the Nicobar Islands, but it was not taken over into Austrian ownership.

The next attempt to acquire a colony from the state came from 1859, when Prussia wanted to appropriate the Chinese island of Formosa . Prussia had already met the French Emperor Napoleon III. assured his approval for the company, since at the same time France wanted to acquire colonies in East Asia. Since France was interested in Vietnam but not in Formosa, Prussia was able to take possession of the island. A Prussian squadron , which left Germany at the end of 1859 and was supposed to conclude trade agreements in Asia for Prussia and all other states of the German Customs Union , was also to occupy Formosa, but because the squadron's strength was too weak and in order not to endanger a trade agreement with China, the Order not executed. With a cabinet order of January 6, 1862, the ambassador, Count Eulenburg , who accompanied the squadron, was “released from carrying out the orders placed with him to determine an overseas territory suitable for a Prussian settlement”.

Nevertheless, a ship of the Prussian squadron, the Thetis , was supposed to call at Patagonia in South America for an exploration as a colony, whereby the Prussian naval command was mainly thinking of creating a naval base on the South American coast. The Thetis had already reached Buenos Aires when the ship's commanding officer ordered the trip home due to the exhaustion of the crew after years abroad and the need for an overhaul of the ship.

Bismarck's rejection of colonial acquisitions (1862–1878)

After the German-Danish War in 1864, circles willing to colonize Prussia tried to take possession of the previously Danish Nicobar Islands . Denmark, for its part, offered the Danish West Indies in vain in 1865 in order to prevent the complete loss of Schleswig . In 1866 and again in 1876 the Sultan of the Sulu Islands , which lie between Borneo and the Philippines, made an offer to place his islands under the protection of Prussia or the Empire, which was refused both times. In 1867, the Sultan of Witu asked the traveler Richard Brenner to obtain a Prussian protectorate over his land, which was not even considered in Berlin.

In the constitution of the North German Confederation , which came into force in 1867 , Article 4 No. 1 also included “colonization” as one of the matters under “federal supervision”; this constitutional provision was adopted unchanged in the 1871 constitution of the German Empire .

At Otto von Bismarck's request, the warship Augusta sailed in the Caribbean in 1867/68 to fly the flag for the North German Confederation. At the personal insistence of the Commander-in-Chief of the Navy of the North German Confederation , Adalbert von Prussia , and without Bismarck's consent, the Augusta commander , Franz Kinderling , negotiated a naval base in Puerto Limón with the President of Costa Rica . Bismarck refused the offer, with regard to the Monroe Doctrine the United States . His desire not to challenge the United States also led him to reject an offer by the Netherlands to set up a naval base on the Dutch island of Curaçao , off the Venezuelan coast.

In 1868, Bismarck had made his rejection of any colonial acquisition clear in a letter to the Prussian War and Navy Minister Albrecht von Roon :

“On the one hand, the advantages that colonies promise for trade and industry in the motherland are largely based on illusions. For the costs which cause the establishment, support and especially the maintenance of the colonies, very often exceed the benefit that the mother country derives from them, quite apart from the fact that it is difficult to justify the whole nation for the benefit of individual branches of trade and industry to draw on considerable tax burdens. - On the other hand, our navy is not yet developed enough to take on the task of emphatic protection in distant states. "

At that time, the policy of the North German Confederation did not focus on the acquisition of colonies, but on individual naval bases . From them the world trade of the federal states should be protected with a gunboat policy in the sense of an informal imperialism. In 1867 it was decided to set up five foreign stations. In 1868, for example, land was bought from Yokohama, Japan, for a German naval hospital, which existed until 1911. Until the Tsingtau in China, acquired by the Reich in 1897, was available as a naval port, Yokohama remained a base for the German fleet in East Asia. In 1869 the East Asian Station was established as the first foreign station by the Navy as a sea area permanently occupied by German warships, which later proved useful when acquiring the colonies in the Pacific and Kiautschou .

In 1869 the Rhenish Mission Society , which had been based in South West Africa for decades, asked the King of Prussia for protection and suggested setting up a naval station in Walvis Bay. The Prussian king was very interested in the proposal, but in the course of the Franco-German War the matter disappeared from the agenda.

The French compensation proposal to take over the French colony of Cochinchina instead of Alsace-Lorraine after the Franco-Prussian War was rejected by Bismarck and the majority of the members of the Reichstag of the North German Confederation in 1870. After the founding of the empire in 1871, he retained this opinion. In the course of the 1870s, however, colonial propaganda gained increasing publicity in Germany. In 1873 the African Society was founded in Germany , which saw its main task in the geographical exploration of Africa. In 1878 the Central Association for Commercial Geography and Promotion of German Interests Abroad was founded , which wanted to acquire colonies for Germany, and in 1881 the West German Association for Colonization and Export was founded, in whose statutes the "Acquisition of agricultural and commercial colonies for the German Empire" was . In 1882 the German Colonial Association was founded, which saw itself as an interest group for colonial propaganda. In 1884 the competing Society for German Colonization was established , which set itself the goal of practical colonization. Both associations merged in 1887 to form the German Colonial Society . Four main arguments were put forward for the acquisition of colonies:

- After their development, colonies would offer sales markets for German industrial goods and thus provide a substitute for the weakening demand in Germany itself after the founder crash of 1873.

- Colonies would provide a catch basin for German emigration, which would not be lost to the nation. Since the emigration had until then mainly aimed at English-speaking countries, the colonial agitator Wilhelm Huebbe-Schleiden feared that if you let it go, Germanness would fall hopelessly behind the Anglo-Saxons demographically.

- As the theologian Friedrich Fabri put it, Germany has a “culture mission”: it has the task of spreading its supposedly superior culture worldwide.

- the acquisition of colonies offers a possibility of solving the social question : the workers would allow themselves to be committed to a fascinating national task and turn away from social democracy; this and the emigration of rebellious masses to the colonies would strengthen the internal cohesion of the nation.

Bismarck remained closed to these arguments and preferred an informal trading empire in which German companies successfully traded with non-European regions and penetrated them economically, but without occupying their territories or establishing their own statehood.

The first cases of colonial expansion overseas were therefore extremely hesitant: in 1876 a friendship treaty was concluded between the German Empire and Tonga , which assured Germany that a coal station would be set up in the Vavaʻu archipelago belonging to Tonga . The German Reich was guaranteed all rights of free use of the necessary land. The sovereign rights of the King of Tonga should, however, remain unaffected. There was no actual colonization. The commander of the warship SMS Ariadne , Bartholomäus von Werner, occupied Falealili and Saluafata on the Samoa island of Upolu on July 16, 1878 "in the name of the empire". The German occupation of the localities was reversed in January 1879 by the conclusion of a "friendship treaty" between the local rulers and Germany. On November 19, 1878, Werner signed a contract with the chief chiefs of Jaluit and the Ralik archipelago , Lebon and Letahalin, on privileges such as the exclusive installation of a German coal station. The Marshall Islands did not become an official German colony until 1885. In December 1878, Werner also acquired a port each on the islands of Makada and Mioko in the Duke of York group , which were placed under Reich protection in 1884 as part of the future German New Guinea protected area. On April 20, 1879, the commander of SMS Bismarck , Karl Deinhard, and the imperial German consul for the South Sea Islands, Gustav Godeffroy Junior, signed a friendship and trade treaty with the "government" of the Huahine Island in the Society Islands, including the German fleet also granted anchor rights in all ports on the island.

Bismarck's colonial policy (1879–1890)

The change in Bismarck's policy with regard to colonies coincided with the period of his protective tariff policy, which began in 1878 to secure the German economy against foreign competition.

The first starting point of his colonial policy related to the protective tariff policy was Samoa in 1879 , where there were strong German economic interests. As Reich Chancellor and State Secretary for Foreign Affairs (Reich Foreign Minister) in June 1879, he recognized the "Friendship Treaty" of January 1879 with Samoan chiefs and supported the German consul on Samoa, so that in September 1879 the consul, together with the consuls of Great Britain and the USA, took over the administration of the city and district of Apia on the Samoan island of Upolu. In the 1880s, Bismarck tried several times to annex Samoa, but failed. The western Samoan islands with the capital Apia became a German colony in 1899.

In April 1880, Bismarck first actively intervened domestically for a colonial matter when he introduced the Samoa bill as a bill in the Reichstag , which was approved by the Federal Council but rejected by the Reichstag. A private German colonial trading company that got into trouble was supposed to be financially absorbed by the Reich.

In May 1880, Bismarck asked the banker Adolph von Hansemann for an elaboration on German colonial goals in the Pacific and the possibilities for their implementation. Hansemann sent his “Memorandum on Colonial Endeavors in the South Seas” to the Reich Chancellor in September of that year , and the territorial acquisitions proposed in it were almost consistently taken or claimed as colonies four years later. The areas in the Pacific claimed in 1884–1885 but not yet taken over were finally transferred to German colonial possession in 1899. Significantly, Hansemann was a founding member of the New Guinea consortium created in 1882 for the acquisition of colonies in New Guinea and in the South Seas .

In November 1882, the Bremen tobacco trader Adolf Lüderitz contacted the Foreign Office and asked for protection for a trading post south of Walvis Bay on the South West African coast. In February and November 1883, Bismarck asked the government in London whether England would take over the protection of the Lüderitz trading post. The British government refused both times.

Since March 1883, the Hamburg wholesaler, shipowner and director of the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce, Adolph Woermann , had been negotiating in strict confidence with the Foreign Office , headed by Bismarck, about the acquisition of a colony in West Africa. The reason for this was the fear of tariffs that Hamburg traders would have to pay if all areas of West Africa came under British or French rule. Finally, in a memorandum of the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce dated July 6, 1883, the application for the establishment of a colony in West Africa was submitted to Bismarck in an equally confidential manner, stating that “such acquisitions only gave German trade in transatlantic countries a more solid position and secure support would; because without political protection, no trade can flourish and advance properly today ”.

After the Sierra Leone Convention between England and France was published in March 1883 , in which spheres of interest were demarcated between the two states in West Africa without taking other trading nations into account, the German government asked the senates of the cities of Lübeck , Bremen and Hamburg in April 1883 for an opinion on it. In their response, the Hamburg overseas traders demanded the acquisition of colonies in West Africa. In December 1883, Bismarck had the Hamburgers informed that an Imperial Commissioner would be sent to West Africa to secure German trade, also to conclude contracts with "independent Negro states", and that a warship , the SMS Sophie , would provide military protection. Furthermore, Bismarck asked for suggestions for this project and asked the Hamburg merchant Adolph Woermann personally for his advice on which instructions should be given to the Imperial Commissioner. In March 1884 Gustav Nachtigal was appointed Reich Commissioner for the West African coast and embarked on the warship SMS Möwe for West Africa in order to conclude the relevant contracts.

The year 1884 marked the actual beginning of the German colonial acquisitions, even though property and rights for the German Empire had been acquired overseas since 1876. In one year, the third largest colonial empire in terms of area was created after the British and French. Following the English model, Bismarck placed several properties of German merchants under the protection of the German Empire. In doing so, he used a phase of relaxation in foreign policy at the beginning of the "colonial experiment", which he himself continued to be skeptical about.

First, the possessions acquired by the Bremen merchant Adolf Lüderitz on the Bay of Angara Pequena (" Lüderitzbucht ") and the adjacent hinterland (" Lüderitzland ") were placed under the protection of the German Empire in April 1884 as German South West Africa . Togoland and the possessions of Adolph Woermann in Cameroon followed in July , in November the northeast of New Guinea ( Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land ) and the offshore islands ( Bismarck Archipelago ), in January 1885 Kapitaï and Koba on the West African coast, in February the East African territory acquired by Carl Peters and his Society for German Colonization and in April 1885 the Denhardt brothers finally acquired Wituland in what is now Kenya . This largely concluded the first phase of German colonial acquisitions.

Flag hoists from August to October 1885 on islands in the Pacific claimed by Spain led to the Caroline dispute and had to be withdrawn.

In October 1885 the Marshall Islands were taken over and finally several Solomon Islands in October 1886 . In 1888 the empire ended the tribal war on the mid-Pacific Nauru and annexed this island as well.

The motives for Bismarck's sudden colonial acquisitions on a large scale are controversial in historical research. The explanations are dominated by two currents, which assume either a “primacy of domestic policy” or a “primacy of foreign policy”. The public pressure caused by the "colonial fever" that has arisen in the German population is cited as a domestic political reason. Although the colonial movement was not very strong organizationally, it managed to introduce its propaganda into social debates. A memorandum sent to Bismarck by the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce on July 6, 1883, initiated by the shipowner Adolph Woermann , is given particular importance in research. The imminent Reichstag election in 1884 and Bismarck's intention both to strengthen his own position and to bind the colonial-friendly National Liberal Party to himself are also seen as domestic political motives. Hans-Ulrich Wehler advocates the thesis of social-imperialism , according to which the colonial expansion served the purpose of "diverting" the social tensions that had arisen from the economic crisis to the outside and thus giving Bismarck's charismatic rule an internal political legitimation . The so-called "Crown Prince thesis", however, assumes that Bismarck tried to consciously weaken relations with England before the expected change of the throne and thus influence the policy of the heir to the throne, who is considered " Anglophile ", in advance.

In the field of foreign policy, the decision to expand is seen as an extension of the concept of European equilibrium from a global perspective: By “dragging along” in the race for Africa , the German Reich wanted to continue to defend its position among the great powers. An approach to France through a “colonial entente” is also seen as a motive. It should have distracted France from thoughts of revenge in relation to Alsace-Lorraine, annexed in 1871 .

In summary, it is no longer believed that the decision to acquire non-European territories represented a radical change of direction in Bismarck's policy. In Bismarck's liberal-imperialist ideal of an overseas policy based on private-sector initiatives, which he had pursued from the start, the declarations of protection did not change much.

Bismarck transferred the trade and administration of the respective German protected areas to the private organizations through state letters of protection . The administration of the acquired areas was initially carried out on behalf of the German Empire by the German East African Society (1885–1890), the German Witu Society (1887–1890), the New Guinea Company (1885–1899) and the Jaluit operating on the Marshall Islands Society (1888–1906). The German colonies in South West and West Africa were also to be administered in this way at Bismarck's endeavor, but neither the German Colonial Society for South West Africa nor the Syndicate for West Africa were willing or able to do so.

These areas came into the possession of the Germans following military demonstrations of power through extremely unequal treaties: In return for a vague promise of protection and a purchase price that was ridiculously low according to German conditions, the indigenous rulers handed over large areas to which, according to African legal understanding, they often had no claim; Often the details of the contract remained obscure due to a lack of language skills. But they played along because the long negotiations with the colonizers and the ritually executed treaty increase their authority enormously. These treaties have now been confirmed by the German Reich; the organizations were granted extensive sovereignty without separation of powers . The Reich reserved sovereignty and certain rights of intervention in the Protected Areas Act of 1886 alone , without this having been specified or made concrete. This reduced the state commitment financially and organizationally to a minimum.

However, this strategy failed within a few years: Due to the poor financial situation in almost all "protected areas" and the sometimes precarious security situation - in South West Africa and East Africa there was a threat of uprisings by the indigenous population in 1888, in Cameroon and Togo there was a risk of border disputes with the neighboring British Colonies, everywhere the societies had proven to be overwhelmed with the establishment of an efficient administration - Bismarck and his successors were forced to submit all colonies directly and formally to the state administration of the German Reich.

After 1885, Bismarck turned against further colonial acquisition and continued his political priorities in cultivating relationships with the great powers England and France. When the journalist Eugen Wolf urged him in 1888 that Germany had to acquire further colonies in order not to fall behind in the social Darwinist understanding of competition with the other great powers, Bismarck replied in 1888 that his priority was still to secure the recently achieved national unity he saw endangered by Germany's central position:

“Your map of Africa is very nice, but my map of Africa is in Europe. Here is Russia, and here […] is France, and we are in the middle, this is my map of Africa. "

In 1889, Bismarck considered Germany's withdrawal from colonial policy. According to contemporary witnesses, he wanted to end the German activities in East Africa and the efforts with regard to Samoas entirely. It was also reported that Bismarck no longer wanted to have anything to do with the administration of the colonies and wanted to hand them over to the Admiralty. In May 1889, Bismarck offered the Italian Prime Minister, Francesco Crispi , the German possessions in Africa for sale - which he responded with a counter offer regarding the Italian colonies .

In this context, the colonies also served Bismarck as bargaining chips. At the Congo Conference in Berlin in 1884/85, Africa was divided up among the great powers. In 1884, in the name of Lüderitz, a treaty was signed with the Zulu king Dinuzulu , which was supposed to secure Germany a local claim to the Santa Lucia Bay in Zululand . In the course of a compromise with Great Britain, however, the request was dropped in May 1885 and Pondoland in South Africa was not recognized as a German colony in favor of England. In 1885 Germany also gave up claims to the West African territories of Kapitaï and Koba in favor of France. The same was true of Mahinland in relation to Great Britain. In 1886, Germany and Great Britain also agreed on the delimitation of their spheres of interest in East Africa.

After Bismarck's resignation in March 1890, the German Reich waived all possible claims north of German East Africa in the Helgoland-Sansibar Treaty of July 1, 1890, which he had still largely prepared. This was to achieve a balance with Great Britain. The German claims to the entire Somali coast between Buur Gaabo and Aluula were also given up, from which the relations with the Triple Alliance partner Italy benefited. In return, German South West Africa was connected to the Zambezi via the Caprivi Strip , with the ultimate goal of connecting German South West Africa with German East Africa via the Zambezi. Under these circumstances, German colonial efforts in Southeast Africa failed again .

World politics under Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Under Kaiser Wilhelm II (1888–1918) Germany tried to expand its colonial holdings. The Wilhelmine era stands for enthusiastic, expansionist politics and a forced armament of the Imperial Navy . The colonial movement had grown into a serious factor in German domestic politics. In addition to the German Colonial Society, it also included the extremely nationalist Pan-German Association founded in 1891 . In addition to the arguments put forward so far, the German colonial movement has now put forward that one must fight the slave trade in the colonies and free the indigenous population from their Muslim slave drivers. These abolitionist demands with a clearly anti-Muslim thrust took on the form of a crusade movement after the so-called Arab uprising on the East African coast in 1888 . In the foreground, however, were questions of national prestige and self-assertion in a social Darwinist understanding of competition between the great powers: Germany as a “straggler” must now demand the share it is entitled to.

The imperial government followed this trend. As part of a new world politics, a “ place in the sun ” (according to the later Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow on December 6, 1897 in front of the German Reichstag) for the supposedly “nation that came too late”, which means, in addition to owning colonies, a say in everyone colonial affairs was meant. This policy of national prestige was in sharp contrast to Bismarck's rather pragmatic colonial policy of 1884/1885.

After 1890, only relatively few areas were acquired. In 1895 concessions were acquired in the Chinese cities of Hankau and Tientsin . In 1897/98 the Chinese Kiautschou with the port of Tsingtau became a German lease area. A neutral zone was established in a 50 km semicircle around the Kiautschou Bay , in which China's sovereignty was restricted by Germany. There were also German mining and railway concessions in the province of Shantung .

The German-Spanish treaty of 1899 added the Micronesian islands of the Carolines , Mariana Islands and Palau in the Central Pacific . With the Samoa Treaty in 1899, the western part of the Samoa Islands in the South Pacific became a German protected area. At the same time the rule within the colonies was expanded, e.g. B. in German East Africa on the kingdoms of Burundi and Rwanda . However, in the Bafut and Hehe war in 1891, Germany also encountered stubborn resistance from ethnic groups in the hinterland of Cameroon and East Africa.

At the instigation of the Reich Post Office for the laying of a future German telegraph cable in the western Pacific, the district administrator Arno Senfft took possession of the island of Sonsorol on March 6, 1901 . One day later the islands of Merir and Pulo Anna followed and on April 12th the island of Tobi and the Helen Reef . The islands were incorporated into German New Guinea .

The attempt of the Navy by Behn, Meyer & Co in Singapore around 1900 to lease the island of Langkawi from the Sultan of Kedah for 50 years failed. The English government intervened through the secret Anglo-Siamese treaty of 1897, which required Britain's consent to the granting of rights by Siam to third powers, and the Sultanate of Kedah , under the government of Bangkok , was forced not to lease Langkawi to the German Empire. The attempt of the emperor in 1902 to acquire Baja California from Mexico - also as a further base for the German fleet in the Pacific - failed.

A colonial reorganization of Africa sought by some colonial propagandists did not take place. The exception here was the acquisition of part of the French Congo area for Cameroon in the course of the Second Moroccan Crisis of 1911 ( New Cameroon ). Germany had asked in vain to compensate Morocco for the entire French Congo colony. The increasing isolation in the circle of the great powers, which in Germany was perceived as "encirclement", was the price for this brisk German colonial-political behavior.

The Colonial Economic Committee was founded in 1896 for the economic development of the colonies .

In 1898 the German Colonial School (Tropical School) was founded in Witzenhausen to train people to move to the colonies in agriculture. The successor institutions are now a subsidiary of the University of Kassel . In 1900 the Institute for Ship and Tropical Diseases in Hamburg started its work for the training of ship and colonial doctors.

After a cattle epidemic in German South West Africa in 1897 , the Herero had spread their surviving livestock far across the German colonial area. However, these pastures had previously been sold to large landowners who now claimed the Herero cattle for themselves. In 1904 the situation escalated to the uprising of the Herero and Nama , which the colony's low-staffed protection force could not cope with. The Reich government then sent a naval expeditionary force and later reinforcements of the protection force. With a total of around 15,000 men under Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha , the Herero uprising was suppressed in August 1904 in the Battle of Waterberg . Trotha issued the so-called extermination order, according to which survivors were driven back into the desert. Of the survivors of the battle, Herero reached British Bechuanaland by the end of November 1904 , thousands fled to the northernmost south-west Africa and thousands perished in the desert. Of the estimated 50,000 Herero people, probably half were killed by 1908. With 10,000 victims, around half of the Nama were also killed. These had previously fought on the German side as an auxiliary force against the Herero until the end of 1904.

In 1905/06 the so-called Maji-Maji uprising took place in German East Africa , in which an estimated 100,000 locals perished, many of them from starvation as the German troops burned villages and fields. The rejection of a supplementary budget to further support the colonial wars led to the dissolution of the Reichstag and new elections at the end of 1906. The Reichstag election of January 1907 (the so-called "Hottentot election ") should decide the future of the colonies.

New colonial policy since 1905

As a result of the colonial wars in German South West Africa and German East Africa, the causes of which lay in the incorrect treatment of the native populations, a reorganization of the colonial administration in Germany, a scientific approach to the use of the colonies and an improvement in the living conditions of the peoples in the Germans Colonies deemed necessary. For this purpose, the highest administrative authority for the colonies, the colonial department, was spun off from the Foreign Ministry (the name for a ministry at the time was "Office") and in May 1907 raised to a separate ministry, the Reich Colonial Office .

It was no coincidence that a successful company renovator from the private sector was won over for the office of State Secretary - in today's parlance, Minister - as the designer of the new colonial policy , Bernhard Dernburg . Dernburg had been in charge of the colonial department since September 1906. He went on trips to the colonies to explore the problems on site and find solutions. At the same time, scientific and technical facilities for colonial purposes were promoted or established in order to develop the colonies on this basis. From the Hamburg Colonial Institute and the German Colonial School , parts of the current universities in Hamburg and Kassel emerged. Medical care has been improved for the locals, schools have been built and corporal punishment has been weakened. Roads, railways and ports were laid out to a greater extent for the economic development of the colonies. Dernburg in January 1909: "The goal must be administratively independent, economically independent, healthy colonies closely linked to the fatherland."

Colonial State Secretary Wilhelm Solf also made trips to Africa in 1912 and 1913. The impressions he gathered were incorporated into his colonial program, which included an expansion of the governors' competencies and a ban on forced labor for Africans. In addition, Solf advocated the idea of a road network in the colonies in order to use fewer load carriers. Wilhelm Solf won over all parliamentary groups with the exception of the right for his comparatively peaceful colonial policy, which was based on diplomacy and skillful power politics instead of military strength.

As a result of this new policy, there were no more major uprisings in the German colonies after 1905 and the economic performance of Germany's overseas holdings increased rapidly. From 1906 to 1914 the production of palm oil and cocoa in the colonies doubled, rubber exports from the African colonies quadrupled, and cotton exports from German East Africa increased tenfold. The total trade between Germany and its colonies increased from 72 million marks in 1906 to 264 million marks in 1913. Due to the economic upswing in the protected areas, customs and tax revenues in the colonies increased sixfold from 1906 to 1914 During the development of the colonies, they had become independent of financial support from the Empire or were on the way to doing so. In 1914 only German New Guinea and Kiautschou and the protection forces in Africa were subsidized.

Preparations for the expansion of the colonial empire

In 1898 and 1913, the German Empire and Great Britain signed agreements to take over the Portuguese colonies. The treaty case was supposed to occur if the government in Lisbon used income from the colonies as security for a loan . In addition, the 1913 treaty gave an additional reason for wanting to end the “mismanagement” of the Portuguese in their colonies.

According to agreements with England, the Portuguese colonies of Angola , North Mozambique , the West African islands of São Tomé and Príncipe and Portuguese Timor were intended to be taken over by Germany. The German right of first refusal existed for the Spanish colony Muni , which was completely surrounded by land by the German colony of Cameroon, and the islands of Fernando Po and Annobon belonging to Muni .

Concrete steps to take over Portuguese colonies were taken in 1914. With the establishment of the overseas study syndicate in February 1914 by the major German banks, the economic takeover of Angola was to be guaranteed. On May 28, 1914, on behalf of the Reich, a German bank consortium bought the English company Nyassa Consolidated Ltd with their property, which included half of northern Mozambique.

In July 1914, the Portuguese government issued a government bond for the economic development of Angola, backed by Angolan customs income, which was financed by a German banking consortium. This fulfilled a crucial contractual provision from the German-British agreement of 1913 on the division of the colonies of Portugal between Germany and England.

On July 27, 1914, the German Chancellor Theodor von Bethmann Hollweg gave the government in London his consent for the publication of the previously secret treaty of 1913 on the intended division of the Portuguese colonies with the reasons for the removal of the colonies from Portugal. The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 prevented further steps in taking over the Portuguese colonies.

The colonies in World War I (1914–1918)

When the First World War broke out in August 1914, the troops in the German colonies were not prepared for a war with European powers. For the African colonies, the German side hoped that the resolution of the Congo Conference of 1885 would be complied with, which in their opinion obligated all colonial states to freedom of trade and peaceful solutions to colonial problems in Africa. However, only a few days after Germany entered the war, hopeless resistance from German troops began in most of the colonies. In the protected areas one trusted in a victory of the German troops in Europe for the recovery of the colonies.

Troops of the Entente , Germany's opposing powers, occupied Togo and Samoa in August 1914. In November 1914, Kiautschou fell and by January 1915 German New Guinea was completely occupied. In the larger protected areas, however, the Germans achieved initial successes, for example in the battles near Garua , Sandfontein and Tanga as well as in the battle for Naulila . With the occupation of the South African exclave Walvis Bay , the province of Cunene in Angola, Portugal, the border town of Taveta and the city of Kisii in British East Africa and the island of Idjwi in Lake Kivu , there was even a slight gain in German territory. With the exception of German East Africa, however, sustained resistance failed due to the comparatively small number of troops and the lack of supplies and heavy weapons.

The 5,000-strong South West African Schutztruppe surrendered in July 1915 against the South African Union troops ten times as strong . The British and French sent a total of 19,000 soldiers and 24 warships to the colony of Cameroon . In spite of this, the German troops did not surrender and finally, in February 1916, passed over to the neutral Spanish colony of Rio Muni in front of the enemy superiority , accompanied by 14,000 Cameroonian natives who did not want to live under the rule of the Entente powers .

From 1917 onwards, the interests of the German Reich in its occupied colonies were taken care of by neutral Switzerland , which was only partially successful under pressure from the Entente.

In German East Africa , the German troops - their maximum number during the war was 16,670 men, 90% of whom were African Askaris - under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck remained undefeated until the armistice in November 1918. However, von Lettow evaded from November 1917 in colonies of Portugal and Great Britain to continue his resistance. Even a several dozen native troops under Captain Hermann Detzner in New Guinea did not surrender and waged guerrilla warfare . When Detzner heard of the armistice, he disbanded his troops, rode out of the mountains to Finschhafen and surrendered to the Australians there in mid-December 1918. Nevertheless, the German colonial property was already lost militarily during the war.

In Germany, even during the war, plans for a closed German Central Africa were pursued. It should extend from Niger to the Kalahari Desert and also include Angola, Mozambique, Belgian Congo and large parts of French Equatorial Africa.

Result of the First World War for the German colonial empire

With the entry into force of the Versailles Treaty in January 1920, Germany lost all colonies. This was justified with "Germany's failure in the field of colonial civilization ": Germany did not bring progress to the areas it ruled, but above all war and forced labor. This thesis had already played a role in British war propaganda, notably in the Government's Blue Book published in London in 1918 . Contrary to what the American President Woodrow Wilson had demanded in his 14-point program of January 8, 1918, the people living in the German colonies were not given the right to self-determination , which they were supposedly not yet ready for, but their country became mandated areas of the League of Nations assigned, who left it to the states of the Entente for administration. This was a compromise between Wilson's self-determination principle and the imperial interests of the European victorious powers: They de facto ruled the territories assigned to them like their own colonies, but had to prove in annual reports that they had abolished forced labor and promoted the well-being of the population and social progress would.

In detail, the following victorious powers were assigned parts of the former German colonial empire:

- Great Britain: German East Africa, parts of Cameroon and western Togo

- France: Cameroon and Eastern Togo

- Belgium: Rwanda and Burundi (formerly part of German East Africa)

- Portugal: Kionga triangle (formerly part of German East Africa)

- Australia: Much of German New Guinea

- Japan : Kiautschou (fell back to China in 1922), the Mariana Islands, Caroline Islands, Marshall Islands and Palau

- New Zealand: Samoa

- South African Union : German South West Africa (continued as mandate area South West Africa )

- Australia, New Zealand and Great Britain together: Nauru

After the Second World War , the UN Trust Council took over the administration of the remaining mandate areas. As the last former colony, Palau became independent in 1994.

Structural conditions in the German colonies

Relationship between locals and Germans

Legal inequality

The relationship between the Germans and the indigenous population in the German colonies was characterized by legal and social inequality, as was common in all other colonial empires. There were two jurisdictions whose affiliation was determined according to racial criteria. The “white”, that is, the German and European population in the colonies, represented a small, highly privileged minority. Their relationship to the indigenous population seldom exceeded the one percent mark. In 1914, no more than 25,000 Germans lived in the colonies, a little less than half of them in German South West Africa, which was most likely to be considered a settlement colony . They enjoyed all the advantages of German law; foreigners of European descent were legally equal to them.

The approximately 13 million “natives” of the German colonial empire, as they were officially called according to an imperial ordinance from 1900, did not become German citizens when German citizenship was first introduced in 1913; they were not even regarded as members of the Reich, but merely as subjects or subjects of the German Reich. The German laws of the Reich only applied to them if they were specifically stipulated by ordinance. In particular, legal recourse was closed to them: they had no legal means against orders from the colonial authorities and first-instance judgments by the colonial courts . For the organization of the courts, see the organization of courts in the former German colonies . The governors were able to issue special provisions for the approximately 10,000 people of Arab and Indian descent who lived in German East Africa. According to the Protected Areas Act, it was possible for “natives” to be accepted into the Reich and also to be passed on to their descendants. The background to this was the fact that the children from mixed marriages automatically acquired German citizenship . This was perceived as a threat to the “German national body ”, which they wanted to keep “racially pure”. After love relationships between the population groups had increasingly developed, the colonies gradually banned "civil marriage between whites and natives" from 1905. Extra-marital sexual relationships were outlawed by society in order to prevent " drugging ". In 1912 the Reichstag debated the possibility of mixed marriages , with the result that the majority parties demanded that the Reich government make mixed marriages possible by law. But the law never came into being. The bans continued until the de facto end of the German colonial empire in the First World War.

Proselytizing, education and health care

In the German imagination, the indigenous population consisted of “children”: people, to be sure, but at a low level of maturity who had to be protected, taught and educated. The German mission societies , which were already active overseas from the 1820s, provided instruction and missionary work . On the Protestant side, these were the Berliner Missionswerk , the Rheinische Mission , the Leipziger Missionswerk and the North German Mission . After the Kulturkampf had subsided in 1890, Catholic missionary societies were also allowed to stand by their side.

These mission agencies set up stations in the colonies where they brought Christianity closer to the indigenous population in addition to elementary education and methods of modern agriculture . In doing so, they had great success, as the collapse of pre-colonial societies caused by the German conquest and the subsequent colonial wars had often brought with it a spiritual crisis and the indigenous population had to face the god of the new masters, who proved to be the superior seemed to have been looking for consolation and support. Since the missionaries had the goal of converting the indigenous population and had the right to meet them with charity , they often saw reasons to protest against their cruel treatment and exploitation by the colonial administration and plantation owners . For self-sufficiency and as model goods , however, they often maintained their own plantations and were therefore dependent on the labor and willingness of the indigenous population; so they often got into a conflict of objectives here. The German missionaries were mostly tolerant of the traditional customs of the indigenous population; even polygyny , widespread in Africa and the South Seas, was often tolerated. Only the Islamic culture that dominates the coast of East Africa was fought by the mission agencies.

Due to the inefficiency of the mission organizations and in order not to provoke conflicts in Muslim areas, state schools were also set up in the German colonies from 1887. A compulsory education did not exist, unlike in the kingdom, but not to the self-confidence of the indigenous population through higher education to strengthen. A few technical schools for handicrafts and agriculture were set up and the German-Chinese University in Tsingtau was the only university in the German colonial empire . The state elementary schools differed significantly from the mission schools in terms of their curriculum : These taught in the mother tongue of their pupils, e.g. in Ewe or Otjiherero , and gave up to 15 hours of religious instruction per week, while German was the language of instruction and useful subjects such as arithmetic dominated .

Since the mid-1890s, the Germans established military stations and hospitals in their colonies , although initially only open to Europeans. "Native" or "colored stations" were set up a little later, but the separation between the races was always maintained. Not least in their own interest, the Germans attached particular importance to the control and prophylaxis of tropical diseases : swamps were drained, quinine was given out against malaria , vaccinated against smallpox and lepers were isolated. To combat epidemics, the Germans brought sick people of different ethnicities and of both sexes together in so-called “ concentration camps ” set up especially for this purpose , from which those affected repeatedly tried to flee because of the associated deprivation of liberty and the sometimes painful examinations that were carried out there. In order to test drugs against sleeping sickness , German doctors also carried out human experiments on sick Africans, which sometimes resulted in death. Successes were achieved above all in the fight against smallpox and plague , while there were still major residues in general hygiene and social medicine : "There are very few old negroes," complained the State Secretary in the Reich Colonial Office in 1908. Only showed towards the end of German rule There are approaches to remedy this, for example through the first occupational health and safety regulations or an improvement in the medical supervision.

Forced labor and violence

The indigenous population had previously lived in subsistence and natural economy . So she was not interested in money. In addition, in many regions agriculture was more of a women's work. The Germans therefore met with little willingness to work in the fields for wages, which they attributed to “notorious indolence and laziness”. As an antidote, they imposed head taxes or hut taxes: in order to obtain the money necessary to settle them, surpluses had to be generated, which was only possible through work on plantations. Those who could not pay were sentenced to forced labor - often far from their home village .

Large parts of the indigenous population thus fell into bondage. Traditional slavery was tolerated because a radical abolition, especially in East Africa, would have brought about the collapse of local economic structures. Around 1900 about ten percent of the population of East Africa were slaves owned by African and Arab elites, and the German colonial administration maintained friendly relations with the slave trader Tippu-Tip in Zanzibar . At the same time, slavery in the German colonies was officially abolished and German propaganda highlighted this as one of the cultural achievements of German colonialism. Therefore, other forms of forced labor and bondage were found in which the mortality rates were high. This also included the import of around 1,000 Chinese coolies to Samoa, New Guinea and East Africa, which were also often recruited under duress.

Corporal punishment , commonly administered with a hippopotamus whip , was the order of the day in forced labor and on the plantations . This instrument became known in Germany as a symbol for the treatment of the indigenous population through several colonial scandals: For example, in 1893 the deputy governor of German Cameroon Heinrich Leist had women flogged by Africans who were unwilling to work in front of their eyes; The men had previously been ransomed from slavery , but Leist now refused them their wages, since the ransom had already paid enough for them. It had already become known the year before that the Reich Commissioner on Kilimanjaro Carl Peters had first whipped his African concubine and her lover and then had them untied.

The everyday violence repeatedly provoked counterviolence from the indigenous population, which was sometimes reflected in bloody uprisings and colonial wars. Both Peters' and Leist's attacks had had such a consequence. The bloodiest uprisings were the Chinese Boxer Uprising in 1899–1901 , the Maji Maji Uprising in East Africa in 1905–1907 and the Herero and Nama Uprising in South West Africa from 1904–1908 , which led to the first genocide of the 20th century. State Secretary Dernburg initiated a large-scale colonial reform in 1907: From now on, colonization should be carried out with “means of preservation” instead of “means of destruction”. The colonial economy was no longer to be shaped by alcohol and arms trading companies, but by missionaries, doctors, railways and science. The hut tax was abolished, the expropriation of indigenous land banned and the punishment restricted.

Dernburg's concept nevertheless remained oriented towards the maximum possible exhaustion of the local workforce by the colonialists. The success was limited: Although the beatings and rods declined significantly from 1905/06 to 1907/08, they increased again afterwards and in 1912/13, with more than 8,000 reported punishments, clearly exceeded the value before the Dernburg reforms. The number of unreported unreported flogging on the plantations will have been considerably higher.

administration

Administration of the colonies by the empire

Since 1899 all "protected areas", with the exception of the Marshall Islands (since 1906 also these), were colonies under the direct administration of the empire.

The top management of the "protected areas" was between 1890 and 1907 with the colonial department of the Foreign Office , which was subordinate to the Chancellor . In 1907 the colonial department was spun off from the Foreign Office and elevated to the status of an office - in today's parlance, a ministry - the Reich Colonial Office , and Bernhard Dernburg was appointed State Secretary of the Reich Colonial Office.

According to the imperial decree of October 10, 1890, the colonial department was already supported by the colonial council, in which representatives of the colonial societies and experts appointed by the imperial chancellor were represented.

The German lease area Kiautschou was administered by the Reichsmarineamt , so not like the other protected areas by the Foreign Office or the Reichskolonialamt.

The highest judicial authority for the colonies was the Imperial Court in Leipzig.

The legal situation in the colonies was regulated more precisely for the first time in 1886 with the law on the legal relationships of the German protected areas, which, after several changes, was called the Protected Areas Act from 1900 . It introduced German law for Europeans in the German colonies via the detour of consular jurisdiction. The Consular Jurisdiction Act of 1879 allowed German consuls abroad to exercise jurisdiction over German nationals under certain conditions . The Protected Areas Act now stipulated that the provisions on consular jurisdiction should also be applied accordingly in the colonies. Insofar as they were relevant for consular jurisdiction, important legal provisions of civil law, criminal law, judicial procedures and the court system of the Reich were also brought into force for the German colonies. In addition, other special colonial regulations were issued over time. For the indigenous populations of the colonies, the emperor initially had the power to legislate. In the course of the following years, the Chancellor and officials authorized by him were also able to issue regulations that regulated administration, jurisdiction or the police, for example. In the German colonies there was a basic structure of a dual legal system that provided for different laws for the Europeans and the indigenous people. No colonial criminal law was codified during the period of German colonial rule.

Administration in the colonies

At the head of the administration of a colony stood the governor , to whom a chancellor (for representation and administration of justice), secretaries and other officials were attached.

The districts , the largest regional administrative units in a colony, were administered by a district official at the head. The districts were partially subordinate to district branches . Another administrative unit in the colonies was the residences . In terms of size, they were to be equated with the districts. But in the administration of the residences the local rulers were granted far greater powers than in the districts, also in order to keep the costs of the German administration as low as possible.

Protection troops existed for the military internal security of the colonies in Cameroon, German South West Africa and German East Africa . The police forces in the colonies were militarily organized police forces .

In the colonies there were protected area courts based on the model of the consular courts. Jurisdiction over the indigenous population, particularly in criminal matters, was transferred to the colonial officials in the colonies. In non-criminal matters, indigenous authorities were also given jurisdiction over their communities, which should judge according to local law.

First-instance district courts and a second-instance higher court were set up for the German population and the other Europeans, who are treated as protection comrades. In Togo, due to the small European population, a separate higher court did not seem appropriate, which is why the higher court in Cameroon also had second instance jurisdiction for Togo.

Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land , the Bismarck Archipelago , the Caroline Islands , Palau Islands and the Marianas (and since 1906 the Marshall Islands including the Providence and Brown Islands ) were united to form a German New Guinea government .

Economy and Infrastructure

Agriculture

The economy in the German colonial empire was predominantly shaped by the primary sector . Manufacturing industries were not built up, rather raw materials were produced for export to Europe. These were mainly agricultural products such as rubber , which was in demand from the bicycle , car and electrical industries booming around 1900 , oil fruits , namely palm oil and copra , which were processed by the chemical industry in Germany, sisal and cotton for textile production, the wide range of so-called colonial goods ( coffee , cocoa , sugar cane , pepper , tobacco , etc.), as well as animal skins, hides and ivory . 1908 began with the planting of bananas for export in Cameroon. Germany had already imported some of these products from these areas before colonization, where they had originally been produced by collectors and mainly exchanged for spirits . The trading houses Woermann and Hansemann had already done good business with this before 1884. In addition to agriculture, there were also approaches to the extraction of natural resources through mining , of which, however, diamond extraction alone in South West Africa became profitable.

Before these resources could be exploited by the colonial rulers, people had tried to make a profit from the land. Based on the legal fiction of the terra nullius , according to which the areas they came to were ownerless , the colonial societies had taken large parts of the arable land and displaced the indigenous population on less good land or in reservations. The huge areas of land acquired in this way, namely in South West Africa, were traded speculatively in Germany , and some of them were actually never developed. These ongoing expropriations also contributed to the frustration of the indigenous population and a source of rebellion.

After the land was developed, three forms of agricultural production became available:

- Plantations: capital-intensive, large-scale monocultures that were cultivated by a large number of indigenous workers who were often held in bondage. This type of economy was mainly found in Cameroon, East Africa and the Pacific.

- Farms: smaller businesses run by Germans that managed with a small number of indigenous workers. This less profitable form of economy, which prevailed in South West Africa, was promoted primarily for demographic reasons in order to channel the largest possible flows of German emigration into the German colonial empire.

- Cash crops : Production by the indigenous population from whom the desired products were bought. This model has been successfully implemented , especially in the Duala area in Cameroon.

There were conflicts between representatives of these three forms throughout the entire period of the German colonial empire: On the one hand, because of the expulsions and expropriations that the establishment of farms and plantations on good land brought with it; on the other hand because of profit opportunities, since the indigenous farmers were in direct competition with farmers and plantation owners. Although the missions were among the latter, they spoke out in favor of indigenous smallholder farmers in order to prevent proletarianization that necessarily went hand in hand with an expansion of the plantations.

To improve the profitability of the colonies, the colonial administration put on the promotion and improvement of tropical agriculture: experimental and curriculum days were built that were open and the indigenous population, also was in the Usambara Mountains , the Biological and Agricultural Institute Amani and one in Cameroon Victoria another agricultural research station built.

Infrastructure and transportation

The German colonies were largely rural. The few urban areas were mostly at the ports and trading points, especially on the East African coast. There was hardly any infrastructure in the European sense. Due to the colonial interventions, the settlement structures changed, especially in the garrison locations and administrative centers. With Lüderitz and Swakopmund, new cities arose on the coast of South West Africa . Settlements with previously barely more than a thousand inhabitants, such as Dar es Salaam , Windhoek or Tsingtau, experienced rapid population growth. The administrations reacted to the social and hygienic grievances that this brought about with rules on road layout and building regulations, as well as a settlement distribution based on racial criteria.

The crucial element of traffic engineering between the colonies and Germany was shipping. The colonies were only connected to Germany by ship, for both freight and passenger traffic. The economic use of the colonies was ultimately the reason for their acquisition and shipping connections had to be expanded or created for this. So the shipping in the colonial traffic and the port areas in the colonies were adapted to the growing needs. In Togo, for example, as almost everywhere in the colonies, there was initially no port for ocean-going ships. It was not until the landing stage in Lome that the conditions were created for the safe loading and unloading of European ships. The colonies were well connected to Europe by shipping. For example, via the state-sponsored Reichspostdampferlinien and the lines operated by private shipping companies such as the all-around-Africa services, which call at ports in both directions around Africa, and the German African coastal services of the German East-Africa Line and the Woermann Line .

With the establishment of the colonies in 1886, the imperial steamship service to the Pacific colonies began and in 1890 the German East Africa Line was founded with state support for a secure connection to the African colonies. In the colonies, the port facilities were expanded accordingly for the constantly increasing sea traffic. The main ports in the German colonies were Lome in Togo, Viktoria , Duala and Kribi in Cameroon , Lüderitz and Swakopmund in Deutsch-Südwestafrika, where landing bridges were built in southwest Africa as in Lome, as the bay-free coast did not allow any protected ports. In German East Africa Tanga and Daressalam, in Kiautschou Tsingtau, where excavators I and II were also stationed for the port excavation, while excavator III was on duty in Swakopmund. In German New Guinea the main ports of Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen , Rabaul and Jap as well as a large number of ports in the island world of the Pacific colony. Samoa had relatively the worst port conditions due to its landscape design. The main port of Apia was just an open roadstead and was actually unfavorable as a port with frequent storms, but since Apia was the main trading center, the difficult port location had to be accepted.

To secure the sea routes, lighthouses were erected and weather stations were set up, which were operated by the Deutsche Seewarte in Hamburg. In Dar es Salaam (German East Africa), Duala (Cameroon) and Tsingtau (Kiautschou) floating docks were operated for the maintenance of ocean-going vessels after 1900 . The dock in Duala was owned by the Woermann Line ; those in Dar es Salaam and Tsingtau belonged to the Treasury .

In the colonies, too, the railroad was the most suitable means of transport for mass transport on land. In the German colonies, however, railway construction did not begin until the end of the 19th century. The reason for this was simply a lack of money, as there were no private investors for railroad construction in the protected areas and the Reichstag did not approve any money for railways in the colonies. Only after the turn of the century did the situation improve, and especially when Bernhard Dernburg took office in 1906 as head of the colonial department, railroad construction in the colonies really got going, because Dernburg was convinced of the importance of the railways for the economic development of the colonies. What then gave the railway construction in the protected areas an additional boost was the unexpectedly rapid economic success of the colonial railway lines. The construction of the railway in the colonies was heavily dependent on the landscape. In German South West Africa, railways could be built quickly and easily, and the country soon had a good rail network for military reasons. In Cameroon, on the other hand, building the railway was expensive and technically difficult because of the huge jungle in the south of the colony with its swamps and many watercourses. In 1914, including the Schantung Railway in China, around 6,000 kilometers of rail lines were completed in the colonies and many major rail projects had been tackled, for example the extension of the Hinterland Railway in Togo, the extension of the Mittelland Railway in Cameroon , and the Amboland Railway to the north of Germany in South-West Africa Landes, in German East Africa the Rwanda Railway to the populous residence Rwanda, in Kiautschou the Kaumi-Hantschuang Railway to connect the southern Shantung to Tsingtau.

The rapid expansion of the railways since Dernburg took office was decisive for the economic upswing of the colonies. There were also points of conflict in the construction of the railway, for example which railway lines should be tackled first, as various economic interests collided, for example the long-standing dispute over whether the Southern Railway or the Mittellandbahn should be built first or at all in German East Africa, and because these projects are an enormous number of tied a few workers in the colonies anyway. The plantations urgently needed workers and a large number of workers were needed to transport goods with porters overland. On the other hand, the railway made it possible for the plantations to transport their products cheaply and new areas were opened up for the plantation economy with the growing railway lines. Every kilometer of new rail line in West and East Africa also reduced the need for carriers. The railway lines were ultimately decisive for the economic success of the colonies. (see also: List of German colonial railways )

Road construction began as soon as the German colonies were acquired. The colonial road network was built and maintained from the compulsory labor service of the local population. A well-developed network of footpaths, bridle paths and driving paths was of great importance for the economy, for military purposes and for travel. Depending on the circumstances, oxen, horses, donkeys, mules and camels were used as pulling and riding animals. In West and East Africa, however, draft or pack animals were often unsuitable because they were killed by an animal disease transmitted by the tse-tse fly . So there human carrier columns were used for the transport of goods, which of course also depended on accessible routes. Whole steamships , dismantled into individual parts, were towed by local porters to their place of use on the East African lakes.

Still famous today is the more than 250 km long road that was laid out by the colonial official Franz Boluminski on the island of Neumecklenburg in German New Guinea, today's ( Boluminski Highway ). Because of a road construction project, there was even an uprising among the population forced to do so. It was the uprising on the Pacific island of Ponape in 1910.

When bicycles came to the colonies around the beginning of the 20th century, with the onset of motorized traffic, the problem of correspondingly developed roads, especially for heavy truck traffic, arose. Motorcycles could use the existing paths without great difficulty, but even with passenger cars the difficulties began, especially at all water crossings, because the existing bridges were not designed for such loads. Therefore, the construction of roads for motor vehicles began. The first attempt was made in the south of German East Africa at the beginning of the 20th century, when they tried the port of Kilwa-Kiwindje at the Indikküste by a motor road to the Nyasa in the southwest of the country to join. The project had to be abandoned due to lack of money, but the construction manager of the road, the colonial officer Paul Graetz , was the first person to cross Africa from Dar es Salaam / East Africa to Swakopmund / South West Africa in a motor vehicle between 1907 and 1909. The new infrastructure task of road construction also had to be financed. In September 1913, for example, the colony of Cameroon raised the import duties for the further expansion of motorways. In 1914, however, there were very few cars and trucks in the German colonies. After all, the Tsingtau Automobile Club was founded in the Kiautschou colony in 1912, a local club of the then Imperial Automobile Club, now the Automobile Club of Germany .

When the colonies were acquired, the German postal system was expanded to include the colonies, and it is no coincidence that the shipping lines to the colonies, co-financed by the Reich since 1886, were called Reichspostdampfer. In addition to the expansion of the usual postal services in, to and from the colonies, telegraphs and telephones later appeared , which were also operated by the Reichspost .

In the years before the First World War, colonial radio stations were set up in order to become more independent from international undersea cables. Since 1912 the German-South West African Aviation Association and funds from the national flight donation have built up aviation in the German colonies and created the first airfields. By the First World War, the establishment of the radio network had progressed so far that operations had been running on the short distances within the colonies for years, while the long-range radio stations between Africa and the Nauen radio station near Berlin were in trial operation. Aviation in the German colonies was still in its infancy when the war began.

Economic balance

Economically, the German colonies were a losing business. Only the smallest and economically insignificant colonies of Samoa and Togo generated a small surplus in the last years of German rule. All other colonies had a passive trade balance with the Reich , i.e. the value of the goods that were delivered from Germany to these colonies (consumer goods for the Germans in the colonies, textiles, metal goods, alcohol and weapons for barter with the indigenous population, capital goods to build the infrastructure), exceeded the value of the deliveries from the colonies to Germany in some cases drastically. In addition, the colonies were not financially self-supporting. In general, each colony formed a closed customs area with its own customs tariff. The vast majority of the customs revenue came from import duties . Only in German South West Africa was there more income from export duties thanks to diamond exports . Because the tax and customs revenues that Germany generated with the colonies remained below the cost of administration and counterinsurgency, most of the German colonies were subsidy projects of the Imperial Colonial Administration. The riot-ridden South West Africa and the infrastructure-intensive Kiautschou were particularly expensive. Exceptions were again Togo and Samoa.

With the end of the colonial wars and the new colonial policy since 1905, the general expansion of infrastructure and the expansion of economic activities in the protected areas, the financial situation of the colonies improved considerably and developed towards a balance between income and expenditure. In 1904 foreign trade in the African colonies amounted to 40,672,000 Reichsmarks in imports and 20,821,000 Reichsmarks in exports. In 1908 imports reached 84,264,000 Reichsmarks and exports 37,726,000 Reichsmarks. In 1912 the African protected areas imported for 128,478,000 Reichsmarks and exported them for 103,748,000 Reichsmarks. So the development is clearly foreseeable.

The colonies played a negligible role in the overall balance of German foreign trade: in 1914, trade with them accounted for less than 2.5% of total German foreign trade. There was no promotion of colonial trade, the colonies were treated as foreign customs policy. Imports from the colonies did not even amount to half a percent of total German imports. The products that were imported from the colonies into the German Empire mostly only covered a very small part of the domestic demand. Apart from copper and diamonds from German South West Africa, they could neither strengthen nor permanently change the position of the German Empire on the world market. The colonies therefore did not provide any support for the economy. In the private sector, however, individual investors, such as the Deutsche Handels- und Plantagengesellschaft, which controlled copra exports from New Guinea, posted large profits.

Post-history

German colonialism after 1918

emergency note from 1922

In Germany after the First World War there was a broad consensus that the annexations were wrong and that one had a right to the colonies. Almost all parties to the Weimar National Assembly , which was elected on January 19, 1919, approved a resolution on March 1, 1919, during the peace negotiations, calling for the return of the colonies. Only seven MPs from the USPD voted against. Particularly outrageous was the accusation that Germany had failed in the area of the so-called “civilization” of the foreign peoples it had subjected to, which had played a central role in the German colonialist legitimation discourse. It was of no use: As a result of the Versailles Peace Treaty, Germany had to give up its colonies. With the exception of German South West Africa, where German settlers still live today (see also Deutschnamibier ), all Germans had to leave the colonies.

Weimar Republic

Even in the early phase of the Weimar Republic , voices were loud that wanted the colonies back, including Konrad Adenauer , then Mayor of Cologne. Adenauer was Deputy President of the German Colonial Society from 1931 to 1933 . From 1924 there was a colonial department in the Foreign Office . It was headed by Edmund Brückner , the former governor of Togo. According to Brückner's guidelines, the return of the colonies of Togo and Cameroon as well as German East Africa was considered the most likely. In 1925 the umbrella organization Koloniale Reichsarbeitsgemeinschaft (Korag) was founded, from which the Reichskolonialbund emerged in 1933 through various intermediate steps . Also in 1925, the former colonial minister in Philipp Scheidemann's cabinet , Johannes Bell , created the “Inter-factional colonial association”, which included party members from the NSDAP to the SPD . In 1925 some settlers returned to their plantations in Cameroon, which they had bought the year before with financial support from the German Foreign Office.

Most Germans did not feel guilty in the sense of allegations in the Versailles Treaty, and many viewed the Allied takeover of the colonies as theft, especially after South African Prime Minister Louis Botha invariably made all allegations made by the Allies during the war about the Germans were set up as colonial rulers, described as baseless and invented. German colonial revisionists spoke of a "colonial guilt lie".

In the 1920s, the German Reich supported colonial companies with government loans, and in 1924 most of the plantations in Cameroon were repurchased with government funding. In anticipation of the regaining of the colonies, the Rendsburg Colonial Women's School was founded in 1926 with the support of the Reich . In 1931 the Institute for Foreign and Colonial Forestry was founded at the Tharandt Forest University .

time of the nationalsocialism

After the takeover of the NSDAP , various efforts have been made to the colonial political determination of the Versailles Treaty revise and recover the colonies. In 1934, the NSDAP set up its own colonial policy office , which was headed first by Heinrich Schnee , then by Franz Ritter von Epp , and it began active activity. However, there was no renewed colonization overseas. What role colonialism actually played in Hitler's politics is controversial in research.

Federal Republic

The former German colonies hardly played a role in post-war politics . However, individual West German politicians called for late or post-colonial tasks to be taken over, for example in the trust administration of Tanganyika and Togo. Within the African freedom movement, too, there were isolated suggestions in the context of decolonization . At the end of 1952, representatives of the Ewe proposed in a memorandum to the UN Trustee Council that Germany should reunite the halves of the country administered by Great Britain and France and lead them to independence (see also German Togobund ). The initiative was not taken up. Adolf Friedrich zu Mecklenburg , the last German governor of Togo, took part in the independence ceremony in 1960 at the invitation of Sylvanus Olympio as a guest of honor.

Efforts to revive the Colonial Warriors Association after the Second World War led to the founding of the "Association of Former Colonial Troops" in Hamburg in 1955, from which the " Traditional Association of Former Protection and Overseas Troops " arose.

The last remnants of the protection area- related legislation survived until the legal expiry of the "colonial societies" in 1975 and tax adjustments in 1992 (see also colonial law ).

Representatives of the ethnic groups of the Herero and Nama , whose ancestors were killed in tens of thousands in the German colony of German South West Africa, today's Namibia , filed a lawsuit against Germany in the USA. A district court in New York upheld a class action lawsuit against the German government in January 2017. The complaint speaks of over 100,000 deaths. This colonial war is considered the first genocide of the 20th century. In March 2017, it was also announced that the government in Windhoek was examining a lawsuit against Germany in the International Court of Justice in The Hague . In this context, there was talk of a compensation amount of $ 30 billion.

Current relations with the former colonies