Battle of the Waterberg

| date | August 11, 1904 |

|---|---|

| place | Waterberg , Namibia |

| output | Escape of the Herero, genocide |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 1392 soldiers + auxiliary troops of the Witboois and Baster | 3500–6000 warriors (plus their families) |

| losses | |

|

28 dead |

unknown, high |

A series of skirmishes between Herero and the German Schutztruppe for German South West Africa and their local allies on the Waterberg on August 11, 1904 is referred to as the Battle of Waterberg . The Herero speak of the battle of Ohamakari ( otjiherero ovita yOhamakari ). After four and a half months of the colonial war between the Herero and the German Empire in German South West Africa , the Herero tribes, a total of over 60,000 people, had gathered with their herds of cattle on the Waterberg. The German military commander, Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha , tried to encircle the Herero in order to defeat them militarily in an encircling battle. This failed due to insufficient planning and the failure of some commanders. The Herero under Samuel Maharero escaped to the Omaheke desert to the southeast, but were no longer a military threat. Trotha had the Omaheke partially cordoned off and cut off the water supply by pursuing troops, so that large parts of the Herero people died of thirst. This action by the German side immediately after the Battle of the Waterberg is considered genocide in science . Around 80 percent of the Herero people lost their lives as part of this genocide . From a German point of view, the battle at Waterberg is a decisive victory. From the perspective of the Herero, the battle of Omahakari marks the beginning of the destruction of Herero society.

prehistory

From the beginning of the Herero uprising in January 1904 to June 11, 1904, the German troops were led by Governor Theodor Leutwein . After four and a half months of war, most of the country was safely in German hands. The Herero had withdrawn as far as the high plateau of the Waterberg in the northeast of the colony. Leutwein planned a concentric action against the Waterberg to force the Herero to surrender. In May 1904 he was replaced as Commander-in-Chief of the Schutztruppe, because Berlin was dissatisfied with the slow course of the war and was looking for a quick military solution. Leutwein's successor, Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha, pursued another war goal, namely the complete submission of the Herero.

According to the prevailing military doctrine of the Germans, the attack on Waterberg was to be a decisive battle, either through a crushing military victory or by forcing the Herero to surrender. To prevent the enemy from retreating, a concentric attack should be conducted. For this purpose, the troops were divided and placed around the Waterberg. Leutwein had already drawn up this plan. But Trotha delayed the attack in order to strengthen his troops further. The transport of troops and supplies over 100 kilometers by ox cart through impassable terrain to the Waterberg took over two months.

At the Waterberg the united tribes of the Herero had gathered under increasingly precarious conditions, a total of over 60,000 people with herds of cattle. It is not known why they did not fled to Ovamboland or British Bechuanaland or disbanded. The number of Herero warriors is estimated at 6,000. The Germans led 4,000 men with 36 artillery pieces and 14 machine guns into the field.

Starting position

Since the German side expected an attempt to break out of the Herero westwards into the area of the colony, Trotha mainly strengthened the western wing under the command of Berthold Deimling . Ludwig von Estorff led the second strongest department in the east, while the weaker units in the north and northeast were supposed to take advantage of the area to block the way there. Hermann von der Heyde led the weakest troops in the southeast with eight guns, but without machine guns. Trotha had his headquarters with the troops in the south under Lieutenant Colonel Müller. Horst Drechsler sees behind this list Trotha's plan to drive the Herero into the Omaheke so that they should perish in the desert. Isabel Hull , on the other hand, argues that this is where German military incompetence manifests itself. Trotha had hoped to fight the decisive battle at the Waterberg, anticipated an attempt to break out to the west and therefore weakened the forces in the south-east, because an attempt to break out seemed the most unlikely here. The exhaustion of his troops and the mistakes of two commanders would have prevented a devastating victory. Matthias Häussler criticizes Drechsler's tendency to portray events intentionally and deterministically. In doing so, he stylized the Herero as a mere plaything of the German war machine without taking them seriously as an opponent, and thus reproduced the self-image of the colonizers.

Fighting

The battle began on the morning of August 11, 1904, when Deimling's troops advanced from the west and Estorff's troops from the east on the Waterberg. According to the plan, they should not advance further south until the second day. While the units in the north and north-west should only intervene if the Herero tried to break through with them, troops under Müller in the south and under Heyde in the south-east had the task of concentrically attacking the Hamakari waterhole. This should encircle the Herero opposite Deimlings and Estorffs troops. When Heyde heard artillery fire, however, he was advancing in the wrong direction. When he wanted to turn back, he was stopped by violent Herero fire. He did not contact the headquarters either. So he was unable to reach the Hamakari waterhole.

Fighting occurred mainly in the south and southeast, as well as in the Heyde department. The Müller division was temporarily surrounded during a firefight lasting several hours and lost 12 dead and 33 wounded. Not least under the influence of the German artillery operation, which claimed victims among the 50,000 men, women and children and the herds of cattle, Samuel Maherero ordered the breakout to the southeast, where the least resistance was to be expected. In addition, Deimling had not paused at the Waterberg station, but had advanced. With it he drove the Herero in front of him and through the gap that Heyde had left. The Herero escaped to the Omaheke desert . On the German side, 26 dead and 60 wounded were counted. The number of Herero victims who took their fallen with them whenever possible is unknown. All men who were captured by the Schutztruppler were shot immediately. Women were to be spared. Nevertheless, numerous shootings are documented.

Trotha untruthfully reported a total victory to Berlin. It is true that the Germans had defeated the Herero, who afterwards were no longer able to offer any significant resistance. But Trotha had set her own goals higher. Even if the official war historiography of the German General Staff later denied this, the Herero had not intended to escape. The attempt to perform a concentric operation failed because of the conditions in German Southwest, namely the difficulty of the terrain and the inadequate means of communication. Headquarters was unable to manage the individual departments and was therefore unable to achieve the over-ambitious goals. Trotha later argued that the failure of the encirclement made it impossible to accept offers of surrender by the Herero, as this would have been interpreted as a sign of weakness without a total military victory. On August 13th, he ordered the pursuit to begin, but the troops were exhausted.

Follow up

Von Trotha commanded the German troops into the desert to prevent a reorganization of the Herero. The water points in particular served as strategic goals, which the Herero's trek eastwards followed. The fleeing Herero, however, used up all water points, so that on August 14, von Trotha ordered the march back. After the first persecution of the Herero had to break off after a few hours due to a lack of food and could not actually begin until August 16, the Germans were no longer able to capture the Herero. At most, there were minor skirmishes and retreat skirmishes or attacks on dispersed groups. Captured Herero, including women with children, were killed. From the end of September 1904 there was no prospect of further fighting. The Herero had advanced so far into the Omaheke that the Germans could no longer follow them. On October 2, Trotha issued a proclamation in which it said: “Within the German borders, every Herero is shot with and without a rifle, with or without cattle, I don't take up any more women or children, drive them back to their people, or let them shoot. "

While only a few Herero fell on the Waterberg, most died in the Omaheke Desert, mostly dying of thirst and exhaustion. There was a series of water points, but they were not nearly enough for the mass of the Herero train. German patrols reported that they found holes in the ground, often eight, but also up to 16 meters deep, around the dead who had dug desperately for water. The flight took place during the dry season of winter, which, in addition to night frost, does not suggest new rain until November. Samuel Maharero himself made it with about 1,000 men through the Kalahari to Bechuanaland in the British Protectorate. They offered him asylum on the condition that all hostilities cease. According to a British report, only 1175 Herero reached the British protectorate by the end of 1905, according to the number of asylum applications.

Matthias Häussler argues that Trotha stuck to his strategy until the end of September or beginning of October 1904, namely to put the Herero in a decisive battle. When it became clear that the Herero could no longer be pursued, he had to change his strategy. The proclamation did not necessarily aim at the systematic annihilation of the Herero, but it was inherently a genocidal trait. It led to the final unleashing of autotelian violence. The step from displacement to extermination was only a very short one. When it became clear that the enemy would be exterminated, the procedure was still adhered to and the line to genocidal was crossed.

Culture of remembrance

The “Battle of the Waterberg” is considered the most important event of 1904 in popular German literature. It stands for the victory of the Germans over the “insurgents” and thus the “pacification” of the colony. The strategic military importance of the Waterberg and the fact that there was a German settlement at its foot made the Waterberg an important landmark of the war. Above all, however, contemporary colonial literature stylized the mountain into a landscape steeped in history and a symbol of war. Larissa Förster argues that, unlike large parts of South West Africa, the Waterberg most closely resembled a German landscape and that the landscape became a projection surface for images and feelings that served to heroize and glorify the war.

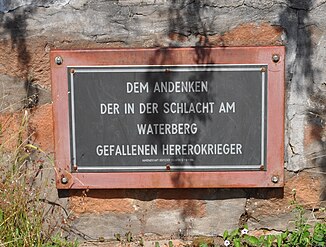

In the local culture of remembrance of the white farmers, the “Battle of the Waterberg” is not represented as a big battle, but as a sequence of several small battles. The fact that there was no “battle of annihilation” speaks against genocide in their eyes. For them, the military cemeteries at the foot of the Waterberg play a bigger role than the memory of the battles themselves. Parts of the former combat area are located on today's guest farm Hamakari , where the graves of German soldiers also bear witness to the battle. Not far from here, Waterberg Wilderness is reminiscent of the battle as part of a historical hiking trail. German-speaking Namibians see the war graves as cultural monuments and as an expression of the roots of German Namibians in the country. Until 2003, a memorial service was held annually at the Waterberg Cemetery. As early as 1905, the German Schutztruppe celebrated the anniversary of the battle. A first official memorial service was held in 1923 at the German cemetery.

For the Herero-speaking Namibians, the Waterberg is not symbolic of the war of 1904. Rather, the climax of the war is considered to be the “Battle of Ohamakari”, named after the waterhole in the immediate vicinity of which the fighting took place on August 11, 1904. It is seen on the one hand as a brave battle, but on the other hand as the event that marked the beginning of the destruction of Herero society, and has become a symbol of displacement, disenfranchisement, oppression and decimation. While Maherero Day on August 26th, the day on which Samuel Maherero was buried in 1923, is considered the main remembrance ritual of the Herero, Ohamakari Day , which was held in Okakarara or the Great Hamakari farm, did not arise in the 1960s could be institutionalized.

On August 14, 2004, the commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Herero uprisings took place in Okakarara . As a participant, the then German Federal Minister for Economic Cooperation and Development Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul expressed an explicit apology for the genocide of the Herero and Nama by the German colonial power. In doing so, she chose the Christian topoi of "common Our Father " and "forgiveness of our guilt". She avoided legal formulas in order not to break the previous line of argument of the federal government regarding compensation payments. Yvonne Robel argues that it was apparently assumed that after the apology claims for reparations from Namibia would be withdrawn. The concept of reconciliation that is expressed is based on reciprocity. The associated rejection of claims for compensation made it easier to name the genocide as such.

source

- The fighting of the German troops in South West Africa . Vol. 1. The campaign against the Hereros. Edit on the basis of official material. from the War History Department I of the Great General Staff. Mittler, Berlin 1906. ( urn : nbn: de: gbv: 46: 1-9067 ).

literature

- Jon M. Bridgman: The Revolt of the Hereros. Univ. of California Pr, Berkeley, CA 1981, ISBN 0520041135 .

- Larissa Förster: Postcolonial Memory Landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 9783593410319 .

- Isabel V. Hull: Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2005, ISBN 0801442583 .

Cinematic interpretations

- Andrew Botelle: Waterberg to Waterberg - In the Footsteps of Samuel Maharero. Windhoek 2014, documentary, 61 minutes. ( Waterberg to Waterberg - In the Footsteps of Samuel Maharero on Vimeo )

Individual evidence

- ^ Jürgen Zimmerer and Joachim Zeller (eds.): Genocide in German South West Africa. The colonial war (1904–1908) in Namibia and its consequences. Links Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-86153-303-0 .

- ^ Tilman Dedering: The German-Herero War of 1904: Revisionism of Genocide or Imaginary Historiography? In: Journal of Southern African Studies . Volume 19, No. 1, 1993, p. 80

- ↑ Dominik J. Schaller: “I believe that the nation as such must be destroyed”: Colonial war and genocide in “German South West Africa” 1904–1907 . In: Journal of Genocide Research (2004), 6 (3), pp. 395-430

- ↑ Reinhart Kößler and Henning Melber : Genocide and Remembrance. The genocide of the Herero and Nama in German South West Africa 1904–1908 . In: Irmtrud Wojak , Susanne Meinl (ed.): Genocide. Genocide and War Crimes in the First Half of the 20th Century . Frankfurt am Main, Campus, 2004 (= yearbook on the history and effects of the Holocaust 8), pp. 37–76 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ Medardus Brehl: "These blacks deserve death before God and people". The genocide of the Herero in 1904 and its contemporary legitimation . In: Irmtrud Wojak, Susanne Meinl (ed.): Genocide. Genocide and War Crimes in the First Half of the 20th Century . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2004 (= yearbook on the history and effects of the Holocaust 8), pp. 77-97 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ George Steinmetz: From “Native Policy” to the Extermination Strategy: German South West Africa, 1904 . In: Peripherie: Journal for Politics and Economics in the Third World . Volume 97–98, 2005, p. 195 (full text in Open Access)

- ↑ Jörg Wassink: On the trail of the German genocide in South West Africa. The Herero / Nam uprising in German colonial literature. A literary historical analysis. M.Press, 2004, ISBN 3-89975-484-0 .

- ↑ Mihran Dabag , Horst founder, Uwe-Karsten Ketelsen: Colonialism, colonial discourse and genocide. Fink Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-7705-4070-0 .

- ^ Walter Nuhn: Sturm über Südwest , Verlag Bernard & Graefe, 2007, ISBN 3-7637-6273-6

- ^ Gesine Krüger : Coping with the war and historical awareness. Reality, interpretation and processing of the German colonial war in Namibia 1904 to 1907. 1st edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3525357966 , p. 49 f.

- ↑ Isabel V. Hull: Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2005, ISBN 0801442583 , pp. 33 f.

- ↑ Isabel V. Hull: Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Gesine Krüger: Coping with the war and historical awareness. Reality, interpretation and processing of the German colonial war in Namibia from 1904 to 1907 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, p. 50.

- ↑ Isabel V. Hull: Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2005, ISBN 0801442583 , pp. 35 f.

- ↑ Horst Drechsler: Uprisings in South West Africa. The struggle of the Herero and Nama from 1904 to 1907 against German colonial rule. Dietz, Berlin 1984, p. 78.

- ↑ Isabel V. Hull: Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2005, ISBN 0801442583 , pp. 37-39.

- ↑ Matthias Häussler: The genocide of the Herero. War, emotion and extreme violence in »German South West Africa«. Velbrück, Weilerswist 2018, p. 165 f.

- ↑ Isabel V. Hull: Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2005, ISBN 0801442583 , pp. 39-41.

- ^ Jon M. Bridgman: The Revolt of the Hereros. Univ. of California Pr, Berkeley, CA 1981, ISBN 0520041135 , p. 124.

- ↑ a b Isabel V. Hull: Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2005, ISBN 0801442583 , p. 41.

- ^ Gesine Krüger: Coping with the war and historical awareness. Reality, interpretation and processing of the German colonial war in Namibia 1904 to 1907. 1st edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, p. 51.

- ↑ a b Isabel V. Hull: Absolute Destruction. Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany. Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2005, ISBN 0801442583 , pp. 41-45.

- ↑ Matthias Häussler: The genocide of the Herero. War, emotion and extreme violence in »German South West Africa«. Velbrück, Weilerswist 2018, ISBN 978-3-95832-164-9 , pp. 158-165.

- ↑ a b Battle of Waterberg ( Memento from September 16, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- ↑ a b Matthias Häussler: The genocide of the Herero. War, emotion and extreme violence in »German South West Africa«. Velbrück, Weilerswist 2018, pp. 184–197, cited above. P. 190.

- ↑ a b Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 9783593410319 , p. 89.

- ↑ Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 187.

- ↑ Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 91 f.

- ↑ Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, pp. 88, 102, 94.

- ↑ Schlach am Waterberg. Hamakari Guest Farm. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ Experiences at Waterberg Wilderness and in the surroundings. Waterberg Wilderness . Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 97 f.

- ↑ Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 125 f.

- ↑ Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 134 f.

- ↑ Larissa Förster: Postcolonial memory landscapes. How Germans and Herero in Namibia remember the war of 1904. 1st edition. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, pp. 248-259, 185, 267.

- ^ Yvonne Robel: Genocide negotiation. On the dynamics of historical-political struggles of interpretation - Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2013, pp. 330–324, esp. Pp. 330–335, 337 f, 342.

Coordinates: 20 ° 28 ′ 36 ″ S , 17 ° 18 ′ 29 ″ E