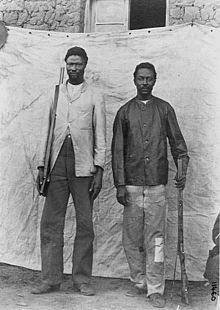

Samuel Maharero

Samuel Maharero (* 1856 ; † March 14, 1923 in Serowe ) was the son of Maharero and from 1890 to 1915 group leader of the Ovaherero in the colony of German South West Africa , today's Namibia , and led the Herero in the uprising against the German protection force .

Life

From 1840 the Herero people had almost constant contact with European missionaries , which meant that the Kapteins sons in particular were instructed in reading and writing. This also happened to Samuel Maharero and obviously with such great success that he, together with his brother Wilhelm, was chosen by missionary Carl Hugo Hahn as a junior priest and was accepted as one of the first students in the Augustineum priestly school founded by Hahn in Otjimbingwe .

After the death of Maharero and others Tjamuaha on October 7, 1890, Samuel Maharero competed with four other possible heirs for the rule. Since he was baptized as a Christian, Samuel Maharero was only left with his father's house in accordance with the Herero inheritance law. For his further claims he found support from missionaries and white traders in Okahandja . Samuel Maharero turned to the German governor Curt von François to secure his rule , who recognized his claim. When Maharero was expelled from Okahandja by other Herero leaders in June 1894, he turned to François' successor, Theodor Leutwein , with a request for help. Leutwein saw this as an opportunity to split Herero society and helped Maharero to victory militarily. Maharero had thereby secured the position of the overlord, but left dependent on the Germans. In the history of the white South West Africans, Samuel Maharero appeared only as a politically willing and powerless, pleasure-addicted weakling. Leutwein, in particular, made devastating judgments about Maharero's political abilities, emphasizing his alleged powerlessness and influence, individual features of personal cowardice and failure in an immediate command situation, without taking into account that Maharero had succeeded in bringing the chief issue together around 1,000 warriors. As the historian Jürgen Zimmerer emphasizes, Maharero was not only a passive victim of a policy of division brought about from outside, but also relied on German support to satisfy his ambitions. This enabled the Germans to play a decisive role despite insufficient military power. Leutwein's policy of divide et impera was successful because its ostensible interests met those of Samuel Maharero, who tried to instrumentalize Leutwein for his own purposes.

In 1897, however, the Herero's economic situation deteriorated dramatically. The rinder plague that broke out in South Africa and a devastating plague of locusts cost the Herero 70 percent of their livestock and forced them to sell more land and eventually even to work with the German settlers. Here, there were repeated attacks - including sexual - by the German farmers, without this being adequately countered by the already existing German jurisdiction. The displeasure of the Herero was further promoted by the increasing dealer nuisance and their lending practice, so that Samuel Maharero in 1901 was forced to submit a formal petition to the governor. Leutwein thereupon forbade the debt-paying land sale on June 7, 1902 and forbade the traders to claim the Kapsteine for the debts of their tribes. Nevertheless, the attacks by the farmers on the Herero remained (the alleged right to "paternal punishment" was used particularly brutally by the Boers who fled South Africa to the southwest ). Another stumbling block was the autocratic conquest of land by the Otavi Mine and Railway Company ( OMEG ). The laying of the rails across the Hereroland in connection with the expansion of the railway network was carried out by this company without authorization or even against the declared will of the Herero landowners.

Since Samuel Maharero's formal petitions were unsatisfactory, he finally mobilized the other Herero leaders in 1903 against the increasing land grab and the constant humiliation emanating from the German colonialists. In advance he tried to win other tribes as allies, such as the former war opponent Hendrik Witbooi ; However, they refused to join the planned uprising out of consideration for the protection treaties that existed with the Germans and, on the contrary, even sided with the Germans. However, Samuel Maharero received unexpected help from the Bondelswart resident near Warmbad . This Nama tribe rose up against the Germans in connection with the registration of their weapons and waged a guerrilla war in the south of the country that tied the main power of the German protection force, so that the rest of the country was largely exposed in terms of troops. So it was not surprising that the Herero uprising triggered by Maharero in Okahandja on January 12, 1904, not only surprised the already outnumbered Schutztruppe, but also overwhelmed it militarily.

The rapid initial success of the Herero led to a rapid expansion of the uprising to the entire Hereroland. Governor Theodor Leutwein tried to find a negotiated solution, but was heavily criticized by both the European settlers and the government in Berlin in view of the farmer families murdered by the rebels. Leutwein was replaced as military commander of German South West Africa and replaced by Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha, who landed on June 11, 1904 with a troop reinforcement of around 15,000 soldiers . As a first measure, he offered a bounty of 5,000 marks for the capture of Samuel Maharero and fought the Herero with all severity. Trotha's so-called shooting order and its effects brought the German troops into disrepute. At the Battle of Waterberg on August 14, 1904, the Herero were defeated and driven into the Omaheke desert, where several thousand of them died of thirst.

Samuel Maharero managed to escape the threatened annihilation with around 1500 members of his people through the Omaheke desert to British Bechuanaland (now Botswana ). He settled in Serowe . There he died in 1923 of exhaustion and heart failure after suffering from stomach cancer for a long time. He left a will in the form of a transcript of his visions, conversations and dictations. In it he interpreted the fate of the Herero as God's punishment for their sins and the survival of some as an expression of his grace.

Maharero's body was transferred to Okahandja on August 23, 1923 and buried there three days later at the side of his father and grandfather. Hereros from all parts of the country had come together. The funeral ceremonies organized by the Herero themselves were based on the ceremony with which high-ranking German colonial officials were buried, such as the state funeral for Joachim von Heydebreck . The honor guard was led by Maharero's sons and the new Herero leader Hosea Kutako . Heinrich Vedder celebrated the mass . For the Herero, the Mahahero funeral was the greatest social and political event since the war, which marked the beginning of a new era for them. They showed themselves again as a self-governing political community. Herero Day is celebrated in memory .

literature

- Jan-Bart Gewald: Herero heroes. A Socio-Political History of the Herero of Namibia, 1890–1923. Currey, Oxford 1999, ISBN 086486387X .

- Gesine Krüger: Coping with the War and Awareness of History. Reality, interpretation and processing of the German colonial war in Namibia 1904 to 1907. 1st edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3525357966 .

- Gerhard Pool: Samuel Maharero. 1st edition. Gamsberg Macmillan, Windhoek 1991.

- Jürgen Zimmerer: German rule over Africans. State claim to power and reality in colonial Namibia (= Europe - overseas, historical studies. Vol. 10). Lit, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5047-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Samuel Maharero in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ^ Heinrich Vedder: The old South West Africa - South West Africa's history up to the death of Maharero in 1890. Martin Warneck Verlag, Berlin 1934, page 496

- ↑ Jürgen Zimmerer: German rule over Africans. State claim to power and reality in colonial Namibia (= Europe - overseas, historical studies. Vol. 10). Lit, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5047-1 , p. 20.

- ↑ Jürgen Zimmerer: German rule over Africans. State claim to power and reality in colonial Namibia (= Europe - overseas, historical studies. Vol. 10). Lit, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5047-1 , p. 23 f.

- ^ Helmut Bley: Colonial rule and social structure in German South West Africa 1894 to 1914 . Leibniz-Verlag, Hamburg 1968, p. 82.

- ↑ Jürgen Zimmerer: German rule over Africans. State claim to power and reality in colonial Namibia (= Europe - overseas, historical studies. Vol. 10). Lit, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5047-1 , p. 24.

- ↑ Jürgen Zimmerer: German rule over Africans. State claim to power and reality in colonial Namibia (= Europe - overseas, historical studies. Vol. 10). Lit, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5047-1 , p. 26.

- ↑ Jan-Bart Gewald: The funeral of Samuel Maharero and the reorganization of the Herero. In: Jürgen Zimmerer and Joachim Zeller (eds.). Genocide in German South West Africa. The colonial war (1904–1908) in Namibia and its consequences. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2016, pp. 171–179, here pp. 173–175.

- ↑ Jan-Bart Gewald: The funeral of Samuel Maharero and the reorganization of the Herero. In: Jürgen Zimmerer and Joachim Zeller (eds.). Genocide in German South West Africa. The colonial war (1904–1908) in Namibia and its consequences. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2016, pp. 171–179, here pp. 177–179.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Maharero | Traditional Maharero Leader ( Traditional Herero Leader ) |

Frederick Maharero |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Maharero, Samuel |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Herero captain and leader of the anti-colonial resistance struggle |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1856 |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 14, 1923 |

| Place of death | Serowe |