Nama (people)

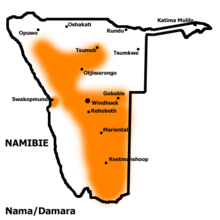

The Nama (own name ǀAwa-khoen = red people ) are a people native to South Africa and Namibia and, like the Orlam , are counted among the Khoi Khoi (who were pejoratively referred to as Hottentots in historical colonial literature). Most of the approximately 100,000 Nama today live in Namibia, there in the southern region of ǁKaras , the former Namaland , and to a small extent also in the south bordering areas of the Northern Cape Province of South Africa, in Namaqualand . They make up about five percent of the entire Namibian population.

In the literature sources the terms Rote Nation (due to their somewhat reddish skin color), Witbooi and Afrikaner are occasionally used as synonyms for Nama or Orlam, but actually denote their subgroups.

"Non-destructive-aggressive society"

The social psychologist Erich Fromm analyzed the willingness of 30 pre-state peoples, including the Nama, to use ethnographic records to analyze the anatomy of human destructiveness . He finally assigned them to the “non-destructive-aggressive societies”, whose cultures are characterized by a sense of community with pronounced individuality (status, success, rivalry), targeted child-rearing, regulated manners, privileges for men and, above all, male tendencies to aggression - but without destructive ones Tendencies (destructive rage, cruelty, greed for murder, etc.) - are marked. (see also: "War and Peace" in pre-state societies )

history

The Nama are referred to by the San as "brother people". They probably immigrated with them or later from Central Africa and settled in South Africa as well as later in Southwest Africa . Traditionally, the Nama operated as nomadic cattle breeders , which initially set them apart from the San, who lived as hunters and gatherers .

Moved to South West Africa

In South Africa, the Nama had various contacts with the Boers , other European settlers and missionaries during the 17th and 18th centuries . During this time, the Nama largely adopted Christianity. They learned to read and write and how to deal with horses as domestic and farm workers for Europeans. The latter opened up completely new hunting opportunities and, in search of better hunting grounds, triggered a new wave of migrations that eventually led the Nama to south-west Africa in the 18th century. The connection between Dutch farmers and Nama women gave rise to other mongrel tribes grouped under the collective term Orlam .

Tribal formation in South West Africa

In South West Africa the Nama initially found a new common center in Hoachanas ; Little by little tribal parts detached themselves because of the cramped grazing conditions, settled in the wider area of Hoachanas and formed new tribes there such as the Topnaar , the Fransman-Nama , the Veldschoendrager , the Bondelswarte , the Swartboois , the Tseibschen Nama , the Groote- doden and the Keetmanshooper Nama .

Only the main tribe, known as the Red Nation , remained in Hoachanas and set the upper kaptein there - with the right to issue instructions to all other Nama tribes with the exception of the Bondelswarte in Warmbad and the Topnaars in Walvis Bay . This right to give instructions included, in particular, the right to assign residence areas to the other tribes in order to ensure in this way that all tribes had sufficient pasture land and sufficient sources.

The nine Nama tribes already settling in South West Africa were joined by another around 1800. It had previously had its headquarters on the Lower Orange River and had fallen into poverty there due to traders and alcohol addiction . Although the southern part of Southwest Africa threatened to get tight, the Oberkaptein Games - the first and only female Kaptein of the Nama - assigned a grazing area near Bethanien to this tribe . The tribe was henceforth called Bethanien-Nama .

Tribal wars

In the period that followed, however, the grazing situation became increasingly critical: on the one hand by the numerically far superior Herero , who were pushing southwards from the north as a result of the severe drought , and on the other hand by the Orlam tribes advancing from the south. Games, however, knew how to make a virtue out of necessity by winning the Orlam - namely the Africans under their Kaptein Jager Afrikaner - for their goals and encouraging them to fight the Herero against the promise of pastureland. The plan worked to the extent that the Herero could be pushed back to the heights of Windhoek in numerous armed conflicts and raids . Nonetheless, there was increasing tensions between the Nama and Orlam tribes, especially among the Oberkaptgemeinschaft von Oasib ǃNa-khomab , which, after initially joining forces against the Herero, finally sparked off in alternating alliances through armed conflicts among themselves (the so-called Orlam War). It was only in the decisive battle of 1867 that the Orlam tribe of the Witbooi succeeded in defeating the Nama tribes allied under the leadership of Oasib so effectively that they were ready for the Orlam Peace of Gibeon on December 19, 1867. This date also marks the end of the supremacy of the Red Nation over the other tribes and ushered in a longer period of relative calm in Southwest Africa - after the disempowerment of the Africans, crowned by the ten-year peace of Okahandja of 1870. The supremacy and thus increased to the Herero the border issue between Herero and Nama, which remained unresolved, led again to violent wars between Nama, Herero and Orlam in 1880.

Appearance of the Europeans

Georg Schmidt worked for the Moravian Brethren in the country as early as 1737–1744 , and new attempts at proselytizing took place from 1792 onwards. From 1814 the London Missionary Society tried with little success to convert the Nama to Christianity, but the Wesleyans were also unsuccessful. From 1842 the Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft operated under the Nama, but the missionaries were expelled in 1847. The diary of Carl Hugo Hahn from 1853 shows with what arrogance, but also with what lack of understanding of what was found and what exclusivity of Christian ideas some missionaries approached the Nama. Hahn came to the conclusion: “The salient traits of their character are: unlimited Arrogance, faithlessness, deceit, mistrust, cunning and unforgiveness and stubbornness and yet also fickleness, murder and greed ... and lust and drunkenness. In addition, there is an ineradicable bitter hatred of all whites, which they incurred through their oppression and contempt. "Hahn, who knew the reasons for the conflicting" character "very well, was also one of the driving forces behind the war from 1863 to 1870 which included Herero, Nama and some Europeans.

In Germany, publications such as Heinrich Vedder's Das alten Südwestafrika from 1934 suggested for decades that it was the sustained efforts of the missionaries and the appearance of the first German colonial officials, who in the early days did not yet have a well-known military cover, that made the situation somewhat relaxed.

In addition to the missionaries and settlers, traders also pitted the African tribes against one another. They brought alcohol and above all weapons and ammunition into the country, which fundamentally changed the balance of power between the tribes. The weapons and other commercial goods had to be paid for with herds of cattle for lack of money . This encouraged mutual cattle robbery and made some tribes visibly impoverished.

From Kido Witbooi to Hendrik Witbooi

After 1870 the Afrikaaner tribe was isolated and the rise of the Witbooi began. They had only appeared in the country in 1863 - after them only the Rehoboth Baster came in 1870 - and were initially called Khowesene (beggar). Kido Witbooi led them from Oranje to Gibeon in 1875 and his grandson Hendrik Witbooi became their captain here .

In 1880 Hendrik had his first voice vision. In 1884/85 he broke with his father Moses, because he considered his cattle theft to be incompatible with his Christian ethics. He moved north with the Christian part of the tribe. He was guided by the Old Testament idea of Moses leading his people into the Promised Land . Although the Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft fought against Witbooi's messianic ideas and allied with the German colonial power, Hendrik Witbooi managed to become captain of all Witbooi. In 1890 he could call himself OberKaptein von Groß-Namaqualand .

Confrontation with the colonial power

The German Reich Commissioner had to quickly retreat to the British Walvis Bay , but still forced the Herero to sign a protection treaty. For his part, Hendrik concluded a peace treaty with the Herero in 1892. But in 1894 he too had to submit to the protective power and move to the (inalienable) Gibeon reserve, which the Witbooi still inhabit today. Hendrik was allowed to keep weapons and horses, but had to achieve military success and allow the Rhenish Mission Society again.

The German protecting power tried to exploit the tribal differences in favor of their settlers and miners. In addition, a rinderpest in connection with a malaria epidemic in 1897 drove the Herero into increasing poverty and debt. Railway lines, shrinking pastures, contempt, mistreatment and racist judgments by the courts drove them into a hopeless uprising.

The first military conflict developed from the colonial administration's counting and registration plans at the Bondelswarte-Nama in Warmbad in October 1903, which dragged on until the end of the year and only after the deployment of reinforcement troops from the north of the country on January 27, 1904 the Kalkfontein peace treaty ended.

As a result, the center of the country was without sufficient military occupation, which made it impossible for the colonial administration in Windhoek to respond adequately to the beginnings of the Okahandja-based Herero uprising on January 12, 1904. This enabled the Herero to have quick initial successes, but the uprising cost around four fifths of the tribal members their lives.

Role in the Herero uprising

On January 28, 1904, Hoachana became a German garrison and thus finally lost its role as the capital of the Nama. The Nama were not involved in the further clashes in the context of the Herero uprising , except as auxiliary staff of the German protection force . This was particularly true of the Orlam tribe of the Witbooi and the tribe of Bethanien , which actively fought on the German side in the Battle of Waterberg . It was only after the victory over the Herero that they began to feel resentful and distrustful of the colonial power.

Nama uprising against the colonial power

On October 3, 1904, immediately after the Herero revolt was put down, and the day before the infamous Trotha proclamation , the Nama, who had previously been allied with the Germans, changed sides under their captain Hendrik Witbooi and turned against the German colonial power. Hendrik Witbooi terminated the imposed protection and assistance pact. Apparently he had taken seriously the threats made during the Herero uprising that they would suffer the same fate. Jakobus Morenga , often also called Jakob Marengo, had been waging a guerrilla war since July, which Simon Kooper continued until February 1909. Kopper led the Nama of Gachas and Hoachanas, Kornelius around half of the Bethanians, Johannes Christian von Warmbad the Bondelzwarts.

Immediately after this declaration, the approximately 80-strong Witbooi auxiliary force, which had supported the Germans in the Battle of Waterberg and knew nothing of the new situation, was disarmed and taken prisoner. In the subsequent Nama uprising in the Karas Mountains , the Witbooi, the Fransman-Nama, under said Simon Kooper and Jakob Marengo, and scattered Herero took part. While the Herero sought open battle, the Nama operated in the form of guerrilla tactics . After Hendrik Witbooi's death, the Witbooi capitulated in 1905; however, the uprising was continued by Marengo and Kooper until 1907 and 1909, respectively.

Around 2,000 Nama were interned on the shark island off Lüderitz Bay . Because of the catastrophic prison conditions there, only about 450 survived the internment. The Nama lost about 10,000 members through this war, i. H. their number was almost halved.

The system of forced labor

In 1905 and 1907 the Nama land and cattle were expropriated and they had to secure their livelihood with the European settlers with simple work. Only up to ten families were allowed to live together, and there were only foremen for the small groups . Everyone had to carry a passport stamp with them, none of the others were allowed to be accommodated or fed. Any German could arrest an African without a passport. The new employers were even able to prevent the issue of a passport with which one could change districts. All Nama needed a service book in which the employment relationships were to be proven. Anyone who did not have it was considered a tramp .

De facto, therefore, there was a compulsion to work, as for almost all colonized people. Of the 22,300 men out of a total of 65,000 Africans, around 20,000 were in European service. Severe corporal punishments were accepted, including by the missionaries, and mild sentences were passed even in the event of a fatal outcome. The tribal associations were practically ruined and the Christian communities were now the only centers of life. This system of typical colonial rule was largely adopted and continued during the First World War in South West Africa in 1915 by the Union of South Africa (a Dominion of the British) as the new occupying power.

At the end of the war, around 6,000 Germans were expelled from the former German South West Africa, and in 1920 the League of Nations placed the country under the C mandate of the South African Union.

New colonial rulers

The Ovambo first learned in 1915 that nothing would change in the colonial system. They were subjugated by the force of arms by the South African Union. Of the once 20,000 Nama, exactly 9,781 were still alive. The Bondelzwarts, who in 1922 had to accept the quadrupling of the tax on the dogs necessary for hunting and who rejected the forced captaincy, were bombed by British planes. 130 of them died. The same thing happened to the Rehoboth bastards striving for independence after 638 arrests. The Herero were again forced to resettle by burning down their huts. Violations of labor discipline turned into criminal offenses, the right to dismiss only existed for the respective employer, there was no freedom of organization, the passport requirement began for everyone aged 14 and over.

In contrast, the British, Germans and Boers received limited self-government in 1925. In 1928 one seventh of the European population owned two thirds of the land.

Influence of the NSDAP, separation from the German mission society

From 1924 many Germans organized themselves in the German Confederation . The NSDAP found supporters especially among the young settlers, and so there were disputes with the old settlers. The NSDAP was banned in 1934, the Hitler Youth in 1935 , and in July 1937 also the German Southwest Bund . The Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft, which relied on a renewal of German colonial rule, aroused suspicion in the mandate power of South Africa, so that after South Africa declared war on the German Empire, six missionaries were interned.

At the beginning of 1946 the Nama left the Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft (RMG) and turned to an "Ethiopian" church whose slogan "Africa for Africans" attracted many. On January 2, 1946, leading Nama declared in a letter ("Agitasie teen blanke Sending Genootskappe") that they were leaving the RMG and the Dutch Reformed Church . In doing so, they compared the activities of the RMG with the more successful of the Finnish mission to the Ovambo, they saw no significant progress in a hundred years, had looked up the contempt in the publications of the RMG themselves, and were now hopeless that it would be in the next hundred years would change something among the old missionaries. They also accused the mission society of only thinking about the income and not about building work. The Nama wanted to lead the congregation themselves and set up a church council made up of evangelists, elders and sextons. They would only want to continue working with them if RMG accepted all of their demands. Contrary to this source, Markus Witbooi, one of Hendrik's grandsons, did not sign the letter. However, this is often claimed in the literature; the resentment against this “rebel family” that was widespread was probably exploited at the time.

The first to sign was Zacchaeus Thomas, born in 1886, who had hoped for his successor after the death of the missionary Nyhof. He had even been suggested by the missionary Spellmeyer. But they did not dare to choose, for fear of the growing influence of the Germans at the time, who feared the increasing influence of the Africans. Just as important for the movement was a member of the Witbooi, namely Petrus Jod, born in 1888. His father Isaak, son of Hendriks, had already become shipyard elder in Gibeon in August 1915. But in 1909 President Fennel rejected him as a teacher because he was Nama. Nevertheless, he rose and was even able to represent Pastor Spellmeyer in absentia in 1926 - a great honor.

The title "Pastor" was one of the main goals of the separation movement. The RMG, which was constantly in need of money, soon concentrated its training on the teachers and no longer on the evangelists or pastors, which it would have had to finance itself. The teachers, on the other hand, were paid for by the South African government. In 1935 there were around 100 teachers and as many evangelists in Namibia. From 1934, the 16 main evangelists were allowed to donate the other sacraments as well as those of marriage. But they were denied ordination . The importance of the robe , the garment belonging to the office, is shown by the fact that the Witbooi wore their white hat again and the Damara their top hats. When Spellmeyer left the country to retire in 1939, the only one who had advocated greater independence for the communities left.

The Nama wanted to separate from the Dutch Reformed Church because it had been working more and more closely with the Rhenish Mission Society since 1922. When the parishes of the RMG were supposed to go to the Dutch Reformed Church in 1932, only the only pastor of the RMG in South Africa, Gideon Thomas, resisted. After the end of the war - the Rheinische Missionsgesellschaft was on the verge of bankruptcy - the congregations were all to be handed over to the Dutch Reformed Church in September 1945. The Nama rose against this. The German umbrella organization was canceled on July 6, 1946, but by then it was already too late. The missionaries who no longer lived in their congregations and who mostly took care of the German congregations had completely wrongly assessed the movement. Two days after the nama was written, the field leadership installed a missionary in Keetmanshoop, although the congregation refused him.

The missionary Rust's leaflet, in which Germans had been warned of the “racial disgrace”, had long since discredited the mission society, especially Provost Wackwitz, who had suggested “in the event that SWA becomes a German colony again”, “that half-breeds, who are already 15/16 white again, and those who are 7/8 white, but have also served in the German army and should receive German Reich membership. "

Further negotiations failed and two-thirds of the teacher-evangelists and one-third of the congregation resigned. They entered the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AMEC), recognized in South Africa since 1901. Your bishop resided in the USA , and South West Africa became the 15th province of this Methodist Church . For the first time since 1850 a Nama became a pastor. But the National Party , which had ruled Pretoria since 1948, refused to recognize the AMEC schools until 1962.

Further separation movements prompted the Rhenish Mission Society to found the Evangelical Lutheran Church in South West Africa (Rhenish Mission Church).

Independence Movement, Namibia

After the South African racial policy had tightened according to the plans of the Odendaal Commission and in 1960 the South West Africa People's Organization ( SWAPO ) was created, the Nama could no longer escape the civil war. Hendrik Witbooi, a son of Markus Witbooi, joined SWAPO in 1976.

After the leader of SWAPO, Samuel Shafishuna Nujoma , who ruled from the independence of Namibia in 1990 until March 21, 2005, Hifikepunye Lucas Pohamba succeeded him as the country's second president.

language

Well-known Nama personalities

see also the chapters of the Nama

- Jonker Afrikaner (1790–1861), tribal leader

- ǃNoreseb Gamab

- Jakob Morenga (around 1875–1907), leader of the Herero and Nama uprising

- Cornelis Oasib (around 1800–1867), head captain of all Nama

- Simon Kooper (unknown – 1913), captain of the so-called Fransman-Nama

- Hendrik Witbooi (around 1830–1905), captain of the Orlam, the Witbooi, a people related to the Nama

literature

- Helmut Bley: Namibia under German rule. LIT, Münster 1996, ISBN 3-89473-225-3

- Tilman Dedering: Hate the Old and Follow the New. Franz Steiner, 1997, ISBN 978-3-515-06872-7

- Lothar Engel: Colonialism and nationalism in German Protestantism in Namibia 1907 to 1945. Contributions to the history of the German Protestant mission and church in the former colonial and mandate area of South West Africa. Frankfurt 1976

- Patricia Hayes: Namibia under South African rule. James Currey, 1998, ISBN 978-0-85255-747-1

- Helga and Ludwig Helbig: Myth German Southwest. Namibia and the Germans . Weinheim, Basel 1983

- Stefan Hermes: Trips to the Southwest: The Colonial Wars against the Herero and Nama in German literature (1904-2004). Königshausen & Neumann, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8260-4091-7

- Hartmut Leser: Namibia. Klett country profile, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-12-928841-4

- Gustav Menzel: The churches and the races. South African problems , Wuppertal 1960

- Helmut Rücker, Gerhard Ziegenfuß: A skull from Namibia - head held high back to Africa . 3. Edition. Anno-Verlag, Ahlen 2018, ISBN 978-3-939256-75-5 .

- Frank O. Sobich: "Black beasts, red danger". Racism and Anti-Socialism in the German Empire. Campus Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-593-38189-3

- Jörg Wassink: On the trail of the German genocide in South West Africa: The Herero / Nama uprising in German colonial literature. A literary historical analysis. Meidenbauer, 2004, ISBN 978-3-89975-484-1

- The Witbooi in South West Africa during the 19th century: source texts by Johannes Olpp, Hendrik Witbooi jun. and Carl Berger. published by Wilhelm JG Möhlig, Köppe, Cologne 2007, ISBN 3-89645-447-1

- Joachim Zeller; Jürgen Zimmerer (Ed.): Genocide in German South West Africa - The Colonial War (1904–1908) in Namibia and its consequences. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 978-3-86153-303-0

Web links

- The first German genocide, n-tv.de Interview with Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zimmerer from the University of Hamburg

- The Nama Uprising, website of the German Historical Museum

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kuno Budack: The "Red People" from the South. in: Tourismus, October 2014, p. 6

- ↑ Erich Fromm: Anatomy of human destructiveness . From the American by Liselotte et al. Ernst Mickel, 86th - 100th thousand edition, Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1977, ISBN 3-499-17052-3 , pp. 191-192.

- ↑ Menzel, p. 11.

- ↑ Cf. (PDF, 160 kB) Walter Nuhn, The lot of the prisoners of war Herero and Nama on the Haifischinsel near Lüderitz 1905 to 1907 (PDF; 160 kB)

- ↑ Engel, Kolonialismus, p. 32.

- ↑ Helbig 168.

- ↑ A detailed description of the war can be found in R. Freislich, The Last Tribal War. A history of the Bondelswart uprising which took place in South West Africa, Cape Town 1964.

- ↑ Martin Eberhardt: Between National Socialism and Apartheid. The German population group of South West Africa 1915 - 1965 , Dissertation Konstanz 2005, Lit 2005 (3rd edition), ISBN 978-3-8258-0225-7 , Section 7.1: The German South West Federation and its Gleichschaltung , pp. 385ff.

- ↑ a b Th. Sundermeier: But we were looking for community. Church becoming and church separation in South West Africa , Witten, Erlangen 1973.

- ^ K. Schlosser: Native churches in South and South West Africa. Their history and social structure, results of an ethnographic study trip in 1953 , Kiel 1958, 88f.

- ↑ Angel 401.

- ↑ Note: This article contains characters from the alphabet of the Khoisan languages spoken in southern Africa . The display contains characters of the click letters ǀ , ǁ , ǂ and ǃ . For more information on the pronunciation of long or nasal vowels or certain clicks , see e.g. B. under Khoekhoegowab .