Promised Land

Promised Land is a name that appeared in the early modern period for the land of Israel , which was also called the Holy Land . The term translates from Latin terra promissionis and emphasizes the aspect that, according to the biblical description, God confirmed his land promise with an oath, that is, "vowed" ( Gen 26.3 LUT ). The modern term is "land of promise".

Hebrew Bible

The term "promised land" takes up the idea that the land of Israel is a gift from God, a concept that is particularly developed in the book of Deuteronomy and is close to the concept of a conquest of the Israelites : a military conquest, combined with the enforcement of the Bans on the resident population.

In the Deuteronomistic History (e.g. 2 Kings 23,27 LUT ) and the prophets (e.g. Jer 5,19 LUT ) the loss of statehood is explained by the fact that Israel did not live in the land according to God's commandments. This is linked to the hope for the future that the people in the Jewish Diaspora will be able to return to the country and start over there (e.g. Isa 8,7-8 LUT ). “According to the current state of research, the land promises were unfolded in a phase of landlessness - during the exile in the 6th century BC. The image of the promised land here becomes an image of hope ... "

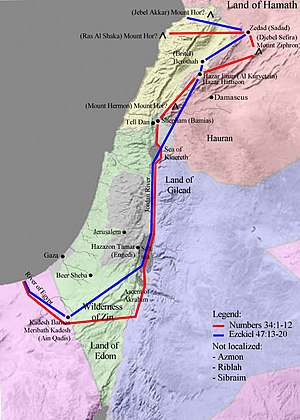

The boundaries of the promised land are determined differently in the Hebrew Bible; these are ideal ideas:

- Gen 15,18 LUT : northern border on the Euphrates, southern border on the "brook of Egypt" (Nile or Wādī l-'Arīš ).

- Judge 20,10 LUT : From Dan in the north to Beersheba in the south.

- Num 34,12 LUT : Jordan and Dead Sea as the eastern border.

- Jos 1:14 LUT : Areas east of the Jordan also belong to the promised land.

Other concepts describe the land of promise by adding up the territories that were assigned to each of the tribes of Israel ( Book of Joshua ) or as an ideal blueprint for the future ( Book of Ezekiel ).

Rabbinical literature

The land of Israel has a unique quality in rabbinical literature in that all the do's and don'ts of the Torah can be practiced here. However, there is no rabbinical consensus on the country's borders. The territory gained through a legitimate war is also considered the Land of Israel.

Zionism

In his main work Der Judenstaat, Theodor Herzl advocated the thesis that every Jew carries something of the Promised Land within him, which he transfers to the state to be built: “... Everyone carries a piece of the Promised Land over: the one in his head and the one in his Poor, and those in their acquired property. "

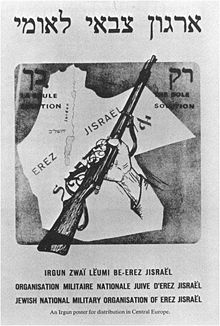

Alongside anti-Semitism, the biblical land promise was the decisive motive for the Jewish settlement in Palestine since the 19th century and the re-establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 on the basis of Zionism . The Revisionist Zionism was based on the Biblical borders of Israel and therefore aimed at a Jewish state, which also included areas in Transjordan. With the 1982 Lebanon War , the northern border of the Promised Land came into the focus of the Israeli religious right. In particular, Yisrael Ariel emerged with studies of the territorial extent of the promised land, which he said includes all of Lebanon and parts of the states of Syria, Iraq and Kuwait.

The religious metaphor of the promised land is also used by secular ultra-nationalists for the ideological justification of a Greater Israel. As a member of the Techija party put it: “To me the Bible is sacred. In my eyes it is even more sacred than it is for a religious person. ... I don't think God said anything to Abraham. I see the geopolitical mission of the people of Israel for future generations in the promised borders. ” In the 1950s and 1960s, Israel Eldad called for a Jewish state from the Nile to the Euphrates, and in the 1970s still as a minimum state territory that included the Sinai and the Euphrates Included Jordan.

Gush Emunim represents a form of religious Zionism that does not base land claims on the fact that the area in question was inhabited by Jews in the past, but that it is a promised land that will be settled in the future. In this sense, Moshe Levinger urged his followers to “redeem” the market in the Palestinian city of Qalqiliya .

Christian tradition

Paul sticks to the connection between the believers in Jesus and the people of Israel, while the land of Israel takes a back seat. The connection with this country seems less important. "The land of the new people of God is the world", not in the sense of Christian world domination, but in the sense of worldwide mission.

Origen mentioned in the 3rd century AD that his Jewish contemporaries referred to earthly Judea as the "Promised Land". In his opinion, Judea, like every earthly territory, is under the curse of the Fall , and the Christians hoped for a heavenly land of promise in the hereafter. Tertullian mentioned that Jews referred to Judea as the "Holy Land" (this is where the term first appears in Christian literature) and distanced himself from it. Holy Land - that is the body of Christ. But there was a counter-movement to this spiritualization of the Promised Land. With the beginning of pilgrimage tourism in the 4th century, the ideas of a Christian Holy Land and a Holy City (Jerusalem) established themselves.

The Crusaders imagined themselves to be the new Israel charged with conquering the Promised Land. The religious conception of the promised land was also effective in the European colonization of North America , South Africa and other non-European areas.

When Martin Luther , the term "Promised Land" often encountered with respect to the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt under the leadership of Moses. He cited affirmatively reports from pilgrims to Jerusalem that the Holy Land had nothing worthy of praise in itself at present, but had become sterile because of the wickedness of its inhabitants. A Count von Stolberg crossed the Holy Land and then said that he preferred his own country.

Since the Enlightenment, the idea of a holy land was no longer comprehensible for liberal Christians. A country or a city cannot have a special closeness to God as an essential characteristic. “Zion”, for example, could now be metaphorically called any place where people of good will lived together. The land of Israel, however, retained its particularity as the scene of biblical history and (for Christians) the life of Jesus.

The EKD emphasizes that a distinction must be made between the secular state of Israel and the “land as a gift from God”; the Bible says there are no boundaries between the land of promise and no form of organization for Israel's dwelling in its land. Christian Zionism is explicitly rejected. On the other hand, the EKD respects the importance of the country for Jewish self-image: "When Christians stand up for the right to life of the Jewish people in the land of the fathers, they respect that the connection between people and land is indispensable for Judaism."

Web links

- J. Cornelis de Vos: Land. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

literature

- Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. A guide . Published on behalf of the EKD, the UEK and the VELKD, Gütersloh 2012, ISBN 978-3-579-05966-2 .

- Walter Kickel: The promised land: the religious significance of the state of Israel from a Jewish and Christian perspective . Kösel, Munich 1984. ISBN 978-3-466-20248-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. An orientation guide , Gütersloh 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. An orientation guide , Gütersloh 2012, p. 24.

- ↑ Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. An orientation guide , Gütersloh 2012, p. 106.

- ^ Johann Maier : Judaism . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Theodor Herzl: The Jewish State. Attempt at a modern solution to the Jewish question . Leipzig and Vienna 1896, p. 85.

- ^ Ian Lustick: For the Land and the Lord: Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel . New York 1988, pp. 107-108, cf. Yisrael Ariel: אטלס ארץ-ישראל לגבולותיה: על-פי המקורות Atlas of the Land of Israel, Its Boundaries According to Sources, Vol. 1, Jerusalem 1988; Vol. 2, Jerusalem 1993.

- ↑ Ephraim Ben Haim, quoted here. after: Ian Lustick: For the Land and the Lord: Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel . New York 1988, pp. 103 f.

- ^ Ian Lustick: For the Land and the Lord: Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel . New York 1988, p. 104.

- ↑ Michael Feige: Settling in the Hearts: Jewish Fundamentalism in the Occupied Territories . Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2009, p. 45.

- ↑ Jacobus Cornelis de Vos: Holy Land and nearness of God. Changes in Old Testament concepts of land in early Jewish and New Testament writings . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2012, p. 123.

- ↑ Origen: Contra Celsum 7, 28.

- ^ Tertullian: De resurrectione carnis , chap. 26th

- ↑ Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. An orientation guide , Gütersloh 2012, p. 56.

- ↑ Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. An orientation guide , Gütersloh 2012, p. 58.

- ↑ For example: WA 6, 357, 8; WA 49, 539, 30.

- ↑ WA 42, 49, 20-25.

- ↑ Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. An Orientierungshilfe , Gütersloh 2012, pp. 102-104.

- ↑ Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. An orientation guide , Gütersloh 2012, p. 91.

- ↑ Promised Land? Land and State of Israel under discussion. An orientation guide , Gütersloh 2012, p. 90.