Isaiah

| Nevi'im (prophets) of the Tanakh |

|---|

| Front prophets |

|

| Rear prophets |

| Writing prophets of the Old Testament |

|---|

| Great prophets |

| Little prophets |

|

Names after the ÖVBE italics: Catholic Deuterocanon |

| Old Testament books |

|---|

| Pentateuch |

|

| History books |

| Textbooks |

|

| Prophets |

|

"Size"

"Little" ( Book of the Twelve Prophets ) |

|

Isaiah (also Isaias ; Hebrew יְשַׁעְיָהוּ Jəšaʿjā́hû ; Greek Ἠσαΐας Ēsaḯas ) was the first great scriptural prophet of the Hebrew Bible .

He worked between 740 and 701 BC. In the then southern kingdom of Judah and proclaimed the judgment of God ( YHWH ) to this as well as the northern kingdom of Israel and the advancing empire of Assyria . But he also promised the Israelites an eschatological turn to salvation, that is, to universal peace and justice, and for the first time announced a future Messiah as just judge and savior of the poor.

The eponymous book of the Bible gives its prophecy in chapters 1–39. This has been known as Protojesaja since 1892 .

In contrast, almost the entire biblical scholarship traces back the parts of the book as Deutero-Isaiah (Isa 40-55) and Trito-Isaiah (Isa 56-66) to later, exilic-post-exilic prophets and their traders, who refer to historical Isaiah attributed to the Assyrian period (8th and 7th centuries BC).

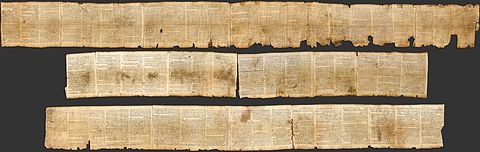

Almost all biblical science is based on a uniform book of Isaiah around 200 BC. In Jesus Sirach assumed. The oldest known complete Hebrew manuscript of the book, the great Isaiah scroll , was dated no later than 150 BC. Created. It plays a prominent role in rabbinic Judaism ( Talmud ) and in early Christianity ( New Testament ). It opens the row of the “rear” prophets in the Jewish Bible canon and that of the “great” prophets in the Christian canon.

Surname

The Hebrew name Isaiah in the Masoretic text יְשַׁעְיָהוּ jəša'jāhû written. It is a sentence name whose subject is יָהוּ jāhû , a short form of "Yahweh" ( YHWH ). His predicate belongs to the root ישׁע jšʿ "save / liberate / help in need". It is also possible to understand the second part of the name as a noun יֵשַׁע ješaʿ "help / rescue" derived from this root . The name therefore means "Help is YHWH / YHWH helped".

construction

The first part (Isa 1–39 or "Protojesaja") is structured by the respective introductory clauses:

| text | content |

|---|---|

| 1-12 | "Seeing Isaiah [...] about Judah and Jerusalem" |

| 13-23 | "Sayings" about foreign peoples |

| 24-27 | so-called Isaiah apocalypse |

| 28-35 | "Woe" calls |

| 36-39 | External reports |

The first 12 chapters run through a four-fold sequence of eviction of sins, announcement of judgment (a historical disaster) and restoration by YHWH and / or a future Messianic King:

| text | content |

|---|---|

| 1.2-20.29-31 | Sin / catastrophe |

| 1.21-26; 2.1-5 | Restoration (zion) |

| 2.6-4.1 | Sin / catastrophe |

| 4.2-6 | Restoration (zion) |

| 5.1-8.23a | Sin / catastrophe |

| 8.23b-9.6 | Restoration (messiah) |

| 9.7-10.19 (+ 20-34) | Sin / catastrophe |

| 10.20-27; 11.1-16 | Restoration (messiah) |

The sections introduced with "Ausspruch für ..." are arranged in groups:

| text | content |

|---|---|

| 13.1-22 14.4-23 14.24-27 14.28-32 |

Babel King of Babel Assur Philistia |

| 15.1-16.14 17.1-11 17.12-14 18.1-7 19 20.1-6 |

Moab Damascus and Israel Assur Kush Egypt Egypt and Kush (act of drawing) |

| 21.1 to 10 from 21.11 to 12 21.13 to 17 22.1 to 25 23.1 to 18 |

Babel Duma / Edom Arabia Jerusalem Tire and Sidon |

Chapters 24-27 form the goal of the foreign peoples' sayings, now related to the whole earth, and a thematic unity: According to Isa 24 YHWH causes the devastation of the whole earth, according to Isa 25-27 he grants salvation in the midst of this universal devastation (25,9; 26.1), namely on "Mountain" (25.6-10) or "Mount Zion" (24.23; 27.13).

Chapters 28-35 are structured by the cry of the lament for the dead ("Woe ...") with changing addressees and interspersed words of grace and salvation:

| text | content |

|---|---|

| 28.1 to 4 28,5f.23-29 |

Ephraim restoration |

| 29.1-14 29.5-8 |

Ariel restoration |

| 29.15f. 29.17-24 |

the people restoration |

| 30.1-17 30.18-26 |

the sons restoration |

| 30.27ff. 32-33 |

Jerusalem (protection - catastrophe - protection) |

| 34-35 | the "devastator" (catastrophe for Edom / return of the redeemed to Zion) |

Chapters 36–39 offer stories about Isaiah and the pre-exilic King Hezekiah , most of which have been handed down in 2 Kings 18–20 EU . These external reports contrast the external and first-person reports in Isa 7–8 and in Isa 39,1–6 finally announce the Babylonian exile (586–539 BC) that took place over 150 years later . This linked the first (1–39) with the second part (40–66), which promised the end of that exile.

Emergence

Isa 1,1 EU ascribes the following “face” to a “Isaiah ben Amoz” who worked “at the time of Uzziah , Jotam , Ahaz and Hezekiah, the kings of Judah”. Isa 7–8 allude to the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel (722 BC). Isa 36–39 and 2 Kings 18–20 confirm Isaiah's appearance under King Hezekiah. Extra-biblical chronicles confirm the siege of Jerusalem described there during the campaign of the Assyrian ruler Sennacherib (703–701 BC). It is therefore certain that this Isaiah was a historical Jewish prophet who appeared in Jerusalem and Judah at least between 734 and 701.

Sir 48: 22-25 EU , the authors of the Greek Septuagint and the Church Fathers considered this prophet to be the author of the entire book named after him. The Talmud, on the other hand, attributed it to a collective of Hezekiah's writers, i.e. several authors. A rabbinical treatise from the 5th century explains the present tense (“God says”) in Is 40.1 with the fact that the following prophecy was also issued after the prophet had resigned. The Jewish commentator Abraham ibn Esra stated in 1145 that the name "Isaiah" is missing from chapter 40: Therefore, this part of the book must have been written analogously to the Book of Samuel after the death of the prophet.

The historical-critical method developed during the Enlightenment, especially from the obvious contradiction in the Book of Isaiah: A prophet who had lived since about 740 BC. Occurred in Jerusalem, would have had to be over 200 years old to experience the end of the Babylonian exile announced from Isa 40. He would have the Persian king Cyrus II , Isa 44:28; 45.1 mentions by name, cannot predict. The Protestant Old Testament scholar Johann Christoph Döderlein explained for the first time in 1775: Because the previously announced Messiah (Isa 9; 11) cannot be equated with Cyrus, another, nameless prophet at the end of the Babylonian exile probably had the part Isa 40ff. composed. Bernhard Duhm helped this thesis to break through in AT research in 1892. He called the author of Isa 40–55 “Deutero-Isaiah” and attributed Isa 56–66 to another anonymous prophet whom he called “Trito-Isaiah”. Since then, at least three different prophets have been adopted, the proclamations of which are later compiled in this book.

While the division of the book into two parts is recognized to this day, the division into three parts and uniform authorship of the sub-parts have been controversial since the 1980s. Isa 40-66 is often explained as a continuous update of various post-exilic editors. The research pays greater attention to the compositional cross-references throughout the book and the intentions of a presumed final editing (synchronous analysis) as opposed to the more widely recognized historical and theological differences (diachronic analysis). This state of research contradicts some exegetes, who continue most of the book to a historical Isaiah of the 8th century BC. Ascribing to Isa 40–66 as real, pre-exilic prophecy. For most historically critical researchers, this view is untenable. However, they recognize many linguistic, structural and content-related arguments for a unified conception of the entire book.

Which texts of the first part come from the historical Isaiah ben Amoz is highly controversial. Uwe Becker (1997) only held the drawing action 8,1.3.16. and the appeal report (6) without obduration motive for authentic. Today's book grew from this core. With Ulrich Berges , Martin Sweeney and Erhard Blum , many researchers today consider a larger body of texts to be Isaiah, which they assign to several phases of his work:

| time | Text portions |

|---|---|

| 740-736 | in Isa 1–2 |

| 735–732 Syrian-Ephramite War |

1.21-31 5.1-24 6 7.2-17.20 8-9.6 15-16.12 29.15-24 |

| 724-720 | 5.25-30 9.7-10.4 10.5-34 14.24-27 17-18 19.1-17 29.1-14 |

| 715–701 Hezekiah's plans for revolt against Assyria |

1.2–18 2.6–19 3.1–9.12–15 3.16–4.1 14.4–21.28–32 22.1–25 23.1–14 28 30.1–18 31 32, 9-14 |

It is possible that Isaiah wrote down his words himself, as suggested by Isa 8,1 EU and 30,8 EU , and / or a group of students ( Isa 8,16 EU ) collected and passed them on. The following texts are considered the oldest collections:

| text | content |

|---|---|

| 5.1 to 7 5.8 to 24 |

Weinberg song woes |

| 6-8 | "Isaiah memorial" ( Karl Budde , 1900) |

| 28.1 to 4 29,1-4.15f. 30.1-5 31.1-3 |

Woes |

Hermann Barth assigns texts that assume Assyria's later decline to a hypothetical Assyrian editorial staff from the time of the Judean king Joschija (~ 640–609 BC). These have supplemented the older text blocks that have already been written down with transitions and new chapters, linked them and possibly already put them together into a book. He includes the texts Isa 7: 1–4.10.18f.21–25; 15.2b; 16,13f .; 20; 23,1a.15-18; 27; 30.19-33; 32.1-8.15-20; 36–37 (taken from 1 Kings 18–19). Analogous to Jer 52 EU and 2 Kings 24 EU , a historical appendix closed this book.

After the Babylonian exile, further texts were inserted into the presumed book of Isaiah from the time of Josiah, which originated in exile and which point to it. This includes at least 13.1.19; 14,4.22; 21.9; 38-39. Chapters 40-66 are either explained as independently developed books that several editors gradually linked with Protojesaja, or as its continuous update. Ulrich Berges dates the final editing for Isaiah as a whole to the time after the new temple was built (around 500 BC), while Odil Hannes Steck dates it to the time of Alexander (around 300 BC).

theology

Isaiah ben Amoz appeared publicly in Jerusalem from around 740 onwards and reacted to the impoverishment of large sections of the population with harsh social criticism, which called for "law and justice" for the poor and saw Israel's survival dependent on it (1.21-26; 5.1 -10; 10.1-3). From 734, the northern Reich of Israel and the southern Reich of Judah wanted to form an alliance against the expanding Assyria. On the other hand, Isaiah advised Ahaz, the then king of Judas, to trust only in YHWH, the God of all Israel. He maintained this fundamental, first commandment-oriented criticism of any policy aimed at military security until the end of his career.

The fall of the northern kingdom (722 BC), which confirmed Isaiah's warnings, can be mirrored in Isa 28: 1-4. From 705 onwards, Judas king Hezekiah set tributes to Assur and provoked the ruler Sennacherib to restore Judas' vassal status with a war. For this he advanced with his army against Jerusalem and besieged it (2 Kings 18: 7-13). Again in this situation Isaiah advocated trust in YHWH (28:12, 16f .; 30:15). In fact, Jerusalem escaped conquest and destruction again at that time.

Isaiah calls YHWH the “Holy One of Israel”: God's holiness, his absolute superiority over all the courses of the world, compels him at the same time to announce God's passionate anger and his judgment on the injustice of the poor. These court announcements call the brutal suppression just as radically by name as the earlier prophets (Amos, Micha). They should open up a new chance in life for the chosen people of Israel. That is why Isaiah speaks of a “remnant” that will be spared (1: 8f .; 30:17). Because he himself experienced the forgiveness of sins (6,7), statements about "hardening" (6,8f.) And Jerusalem's ultimate guilt (22,14) do not contradict other statements that understand God's judgment as purification (1,21ff.) And a suggest alternative behavior that the court can stop. Only after the fall of both kingdoms was this obduracy understood and formulated as an irrevocable prophetic mandate. God's holiness also corresponds to Isaiah's continuous criticism of human arrogance and self-assertion, especially the rulers: the more they want to defend and save themselves, the more they succumb to those powers from which they try to protect themselves, sometimes in rebellion, sometimes in submission. Real peace ("rest") only exists in the sole trust in the God who chose and saved Israel and who will save it again. From this a person can act without fear for others, bring the exhausted rest (28:12) and help the poor to gain their rights. Because the urban upper class (1.21), the northern kingdom and the representatives of Jude (5.7) refused to trust this, their guilt falls on the whole people and makes them sick (1.4–6). Isaiah linked domestic social criticism with criticism of military and foreign policy.

Later texts speak of YHWH's grace, the abolition of incurable disease and guilt on Mount Zion (30:18, 26; 33:24). There YHWH is present for Isaiah, even in a personal crisis (8:17). The threat to Zion, both inside and out, was therefore his main concern. Only by guaranteeing justice for the poor could Jerusalem save itself and once again be called the “city of justice” (1.26f.). Then the peoples would make a pilgrimage there to experience YHWH's legal will and voluntarily disarm (2: 2–4). From there let YHWH rule as true King over all rulers of the world; there he will set up his future Davidic mandate, who will realize his justice (9; 11). There God will prepare the feast of shalom for the peoples (25: 6f.). The exilic-post-exilic parts of the book tied in with these original promises of salvation in terms of language and content. How Isaiah's words affected his contemporaries is not recorded; However, the centuries-long continuation of his prophecy shows the authority he has enjoyed since his appearance.

Isaiah interpreted the threat to Israel from the Assyrians as God's punishment for Israel's deviation from the right path of YHWH. So he saw the Assyrian armies as YHWH's punitive tool: Isa 10,5f. EU : “Woe to Assyria, the stick of my anger! The club in her hand, that's my anger. Against a godless nation I send him and against the people of my anger I deliver him to steal booty and robbery, to trample it down like clay in the streets. " Isa 10,22-25 EU affirms the criminal judgment as fixed and delimits it at the same time: “Israel, even if your people are as numerous as the sand by the sea - only a remnant of them turn back. Annihilation is decided, justice floods in. Because the Lord, the GOD of hosts, carries out firmly decided destruction in the midst of the whole earth. Therefore - thus says the Lord, the GOD of hosts: Do not be afraid, my people, who live on Mount Zion, of Assyria, who strikes you with a stick and who lifts his club against you in the manner of Egypt. Because only a little, a short time, then the anger will be over and my anger will destroy it. "

In summary, Konrad Schmid identifies four subject areas for the theology of Protojesaja (Isa 1-39):

- Judgment and salvation are related. The hardening mandate reflects the theme of judgment prophecy.

- Zion: The historical Isaiah probably comes from Jerusalem priestly circles. Zion, the temple and the presence of Adonai in Jerusalem are guarantees of impregnability. It is inconceivable that Jerusalem will be taken, as exemplified by Sennacherib's failure in 701 (Isa 36-39)

- Kingship of God: The idea of the king is a central statement of Zion theology. Adonai is king and the specific historical rulers that are expressed in the Messiah promises are part of the divine royal rule.

- Messiah: Originally no eschatological, royal salvation figure is meant, but Schmid relates the Immanuel promise to Hezekiah (7:14), the next statements (8,23-9,6) to the birth of Josiah. Only for 11: 1-5 does he consider that it is an authentic ruler's prophecy.

Konrad Schmid highlights five subject areas for Deuterojesaja:

- Election of Cyrus : In Isa 45,1 the Persian king Cyrus is referred to as “anointed Adonais”, in 44,28 Adonai speaks of Cyrus as “my shepherd”. As a result, national religious constrictions are broken open and Adonai becomes the world ruler.

- Monotheism : As an example in Isa. 45,5, Adonai states sole existence, next to which there is “no one else”. The inclusive monotheism of the priestly scriptures is expanded into an exclusive monotheism that denies the existence of other gods. The reason for this are the political shifts: Life in a foreign empire requires a new, greater reflection on God.

- Creation : God is the sole creator of everything else that exists. Creation is a central feature of exclusive monotheism. God's historical acts are understood as acts of creation.

- old and new exodus : The old exodus from Egypt is becoming less important, because in a situation of imprisonment one cannot understand oneself very well as a people brought out. Hence the call for a new exodus, this time from Babylon, becomes necessary. Isa 43: 16-21 also knows a water miracle: God gives his people water in the desert.

- Israel as the patriarchal people : Isa 41: 8-10 is an example of the connection between the people and the name Israel. The promises of the father, especially the land promise, are activated. In addition, classic royal terms are now transferred to the people: Servant Adonais, election, and the phrase "Do not be afraid!"

reception

Church memorial days

- Evangelical: July 6th on the calendar of the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod

- Roman Catholic: May 9th

- Orthodox: May 9th

- Armenian: May 9th and July 6th

- Coptic: the presumed date of his death on September 3rd

See also

literature

introduction

- Ulrich Berges: The Book of Isaiah. Composition and final form (= Herder's Biblical Studies, Volume 26). Herder, Freiburg a. a. 1998, ISBN 3-451-26592-3 .

- Ulrich Berges: Isaiah. The Book and the Prophet (= Biblical Figures, Volume 22). Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-374-02752-1 .

- Ulrich Berges: The Book of Isaiah. An introduction. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016.

- Peter Höffken: Isaiah. The state of the theological discussion. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-15589-0 .

- Otto Kaiser : Isaiah / Isaiah book. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie 16 (1987), pp. 636–658 (introduction and lit.)

- Claus-Dieter Stoll: Controversial authorship using the example of the Isaiah book. In: E. Hahn, R. Hille, H.-W. Neudorfer (Ed.): Your word is truth. Festschrift for Gerhard Maier . Contributions to a Scriptural Theology, Wuppertal 1997, ISBN 3-417-29424-X , pp. 165–187.

Comments

- Wim Beuken: Isaiah 1–12 (= Herder's theological commentary on the Old Testament ). Herder, Freiburg i. Br. U. a. 2003. (367 pages) ISBN 3-451-26834-5 .

- Joseph Blenkinsopp: Isaiah. New York 2000-2003

- Vol. 1: Isaiah 1-39. A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (= The Anchor Bible 19). Doubleday, New York 2000. ISBN 0-385-49716-4 .

- Vol. 2: Isaiah 40-55. A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (= The Anchor Bible 19A). Doubleday, New York 2002. ISBN 0-385-49717-2 .

- Vol. 3: Isaiah 56-66. A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (= The Anchor Bible 19B). Doubleday, New York 2003. ISBN 0-385-50174-9 .

- Franz Delitzsch : Isaiah Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament, 5th edition Gießen / Basel 1984 (reprint of the 3rd edition Leipzig 1879). ISBN 3-7655-9202-1 .

- Karl Elliger , Hans-Jürgen Hermisson : Deutero-Isaiah (= Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament, Volume 11, Partial Volume 1–3). Neukirchen since 1978 (large and comprehensive, scientific commentary on Chapter 40 - end, not yet completed)

- Peter Höffken: The book of Isaiah (= New Stuttgart Commentary - Old Testament). Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk 1993/1998

- Vol. 1: Chapters 1-39. 1993, ISBN 3-460-07181-8 .

- Vol. 2: Chapters 40-66. 1998, ISBN 3-460-07182-6 .

- Jan L. Koole: Isaiah. Vol. 3/3: Isaiah chapters 56-66 (= Historical commentary on the Old Testament). 2001. ISBN 90-429-1065-8 .

- John A. Martin: Isaiah. In: John F. Walvoord, Roy F. Zuck (eds.): The Old Testament explains and interpreted, Volume 3, Neuhausen-Stuttgart 2nd edition. 1998, ISBN 3-7751-1570-6 .

-

Konrad Schmid : Isaiah (= Zurich Bible Commentary - Old Testament 19). Theological Publishing House Zurich 2011.

- Vol. 1: Chapters 1-23. 2011, ISBN 978-3-290-17605-1 .

- Dieter Schneider: The Prophet Isaiah (= Wuppertal Study Bible. AT). Brockhaus, Wuppertal / Zurich 1988/1990. (generally understandable, application-oriented)

- Vol. 1: Chap. 1 to 39, 1988, ISBN 3-417-25216-4 .

- Vol. 2: Chap. 40 to 66. 1990, ISBN 3-417-25217-2 .

- Claus Westermann : The book of the prophet Isaiah chapters 40-66 (= The Old Testament German Volume 19). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1986.

- Hans Wildberger : Isaiah (= Biblical Commentary Old Testament, Volume 10, Partial Volume 1-3). Neukirchen 1972–1982 (large and comprehensive, scientific commentary on chapters 1–39).

Individual studies

- Adrian Schenker: Servant and Lamb of God (Isaiah 53). Assumption of guilt in the horizon of the servant songs (= Stuttgart Biblical Studies 190). Verl. Kath. Bibelwerk, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-460-04901-4 .

- Ernst Modersohn : The unique exchange. Interpretations of Isaiah 53 , VLM Verlag, TELOS books, Lahr 6th edition. 1994, ISBN 3-88002-548-7 .

- Hanna Liss : The unheard of prophecy. Communicative structures of prophetic speech in the book of Yesha'yahu . Works on the Bible and its history 14. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2003, ISBN 3-374-02055-0 .

Fiction

- Hermann Koch (religious educator) : Fly, dove of peace - The story of Isaiah, the prophet who showed the way to peace. A dramatic story. 7th edition, Leinfelden-Echterdingen 1993.

- Hermann Koch (religious educator) : With wings like eagles. The story of the prophet who comforts Israel and proclaims salvation to all peoples (Isaiah, chapters 40-55). Leinfelden-Echterdingen 1995.

Web links

- Read EU - Isaiah on Bibleserver.com , over 40 different Bible translations, in German (including uniform translation, Luther 1984 and Rev. Elberfelder ) and in other languages.

- Jan Kreuch: Isaiah / Protojesajabuch. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Thomas Wagner: Isaiah memorandum. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wilhelm Gesenius , Hebräisches und Aramäisches Concise Dictionary, 17th edition 1995, pp. 325f.

- ↑ Hans-Windried Jüngling: The book of Isaiah. In: Erich Zenger (Ed.): Introduction to the Old Testament. 6th edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, pp. 428-434.

- ^ Ulrich Berges, Willem AM Beuken: The book Isaiah: An introduction. UTB, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016, ISBN 3-8252-4647-7 , p. 10f.

- ↑ Ulrich Berges, Willem AM Beuken: Das Buch Isaiah , Göttingen 2016, pp. 11-13.

- ↑ Ulrich Berges, Willem AM Beuken: Das Buch Jesaja , Göttingen 2016, pp. 13-16.

- ↑ Eddy Lanz: The undivided Isaiah: New light on an old issue. SCM R. Brockhaus, Wuppertal 2004, ISBN 3-417-29487-8 , especially pp. 54-102 .

- ↑ a b c Hans-Windried Jüngling: The book of Isaiah. In: Erich Zenger (Ed.): Introduction to the Old Testament. Stuttgart 2006, pp. 441f.

- ↑ Hans-Windried Jüngling: The book of Isaiah. In: Erich Zenger (Ed.): Introduction to the Old Testament. Stuttgart 2006, pp. 443-446.

- ↑ Hans-Windried Jüngling: The book of Isaiah. In: Erich Zenger (Ed.): Introduction to the Old Testament. Stuttgart 2006, pp. 448-450.

- ↑ Gerlinde Baumann: Understanding God's images of violence in the Old Testament. WBG, Darmstadt 2006, ISBN 3-534-17933-1 , p. 96 f.

- ↑ Konrad Schmid: The Isaiah book . In: Gertz: Basic information of the AT . 5th edition. 2016, p. 336-338 .

- ↑ July 6 in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints