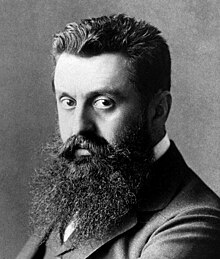

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl ( Hungarian : Herzl Tivadar ; * May 2, 1860 in Pest , Kingdom of Hungary ; † July 3, 1904 in Edlach an der Rax , Lower Austria ) was an Austro-Hungarian writer , publicist and journalist belonging to Judaism . In 1896 he published the book Der Judenstaat , which he had written under the impression of the Dreyfus affair . Herzl was convinced that Jews were a nation and that due to anti-Semitism, legal discrimination and failed acceptance of Jews into society, a Jewish state had to be established. He became its mastermind, organized a mass movement and mentally prepared the way for the foundation of Israel . He is considered to be the main founder of political Zionism .

Herzl's Hungarian name was Herzl Tivadar , his Hebrew first name was Binyamin Zeʾev . He also signed a very large number of letters with Benjamin , in case he did not draw with Herzl or Theodor Herzl . In Hebrew newspapers, e.g. B. in Eliezer ben Jehudas Haschqapha , instead of the original Greek name Theodor, the Hebrew Mattitjahu was used. Herzl's pseudonym in the Zionist weekly newspaper Die Welt was Benjamin Seff, which he founded in 1897 .

Life

Youth in Pest (Hungary)

As a child, Theodor Herzl accompanied his father to church services in the Great Synagogue on Tabakgasse, in the immediate vicinity of which his parents' apartment was located. Herzl's ancestors included both Christian converts and supporters of early Zionism. Two brothers on his paternal grandfather's side converted to the Serbian Orthodox faith as adults . They let themselves be renamed from Mosche Herzl to Lafero Spasoević or from Herschel Herzl to Costa Petrović, which is why their names were not allowed to be mentioned in the Herzl family. Samuel Biliz (1796–1885), on the other hand, brother of Herzl's paternal grandmother, was an early supporter of the Zionist idea. In 1862 he conducted negotiations with Chaim Lorje, a leading representative of the Chowewe Zion . Biliz served as Austrian consul in various Balkan cities and lived in Philippopolis for years before he emigrated to Jerusalem at an advanced age .

Herzl's upbringing by his mother Jeanette (also Johanna Nannette) Herzl (née Diamant; July 28, 1836 in Pest - February 20, 1911 in Vienna) was based primarily on Austrian culture and the German language, as it is for most assimilated Jews in Austria-Hungary was taken for granted. His father Jakob (April 14, 1835 in Semlin - June 9, 1902 in Vienna), director of Hungariabank and later timber merchant, supported his son morally and financially until his death. Among other things, he financed the Yiddish edition of the Zionist magazine Die Welt . Even as a child, Theodor showed writing skills, an interest in technology, and an urge to achieve significant achievements. At the age of ten he decided to become the builder of the Panama Canal , and at the age of 14 he founded the school newspaper Wir .

Theodor (like his older sister) received private lessons from Alfred Iricz a year before he started school at the age of five. He later reported that Theodor and his sister learned to read and write in just two weeks. Theodor in particular took up new things very quickly and without great effort. From autumn 1866, Theodor attended the Jewish primary school Pesti Izraelita Föelemi Iskola . After four years of attending school, he switched to the municipal secondary school in 1870 and to the classic Protestant grammar school in 1875, from which he graduated in 1878 with the Matura . His family wanted to strengthen his bond with Judaism. But she decided against a traditional bar mitzvah . He was "confirmed" at home on May 3, 1873. This was a ceremony that was widespread in Reform Judaism in Germany and was modeled on Christian confirmation .

Studies and early work in Vienna and Paris

In 1878 the family moved to Vienna , where Herzl studied law at the University of Vienna and in 1881 became a member of the Vienna academic fraternity of Albia . In 1882 Herzl read the anti-Semitic pamphlet The Jewish Question as a Race, Moral and Culture Question - With a world-historical answer by Eugen Dühring . Herzl wrote down his views and counter-arguments to Dühring's anti-Semitic allegations in a notebook and at that time began to deal with the subject of anti-Semitism and ways to overcome it. Among other things, he saw the “poisoned pen of personal vengeance” at work in Dühring's writing. With the increase in anti-Semitic ideas in the fraternities, he laid down his bond in March 1883 and thus resigned from the fraternity. Franz Staerk seconded his only length . Herzl was promoted to Dr. iur. PhD . From August 1884 to June 1885 he completed legal practice in Vienna and Salzburg .

On June 25, 1889, in Reichenau an der Rax , he married Julie Naschauer (February 1, 1868 in Budapest - 1907), the daughter of a wealthy Jewish businessman in Vienna. The two had three children: Pauline (1890–1930), Hans (1891–1930) and Margarete (1893–1943), who was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto and died there. Hans Herzl worked at Union Bank in Vienna. He came into contact with Baptists through work colleagues and was baptized with them in July 1924. In the same year he moved to London.

In 1888 Herzl's comedy was given to His Highness at the Wallner Theater in Berlin and in Prague. In 1890 his Viennese operetta Des Teufels Weib , set to music by Adolf Müller junior , was premiered in the midst of the polarization of Viennese theater life directed by Adam Müller-Guttenbrunn .

The young Herzl was shaped by the stereotypes about Judaism that were customary at the time and viewed Jews as inferior, unmanly, incessantly business-minded people without idealism. But he also identified himself with the history of the Jews as victims and admired the Jewish steadfastness in the face of persecution.

Theodor Herzl, who is generally considered to be the founder of Zionism, was originally a German national fraternity. Only when he was expelled from his association because of the Waidhofen resolution did he begin to campaign for the Jewish nation and vehemently demand the establishment of a Jewish state in Israel.

From October 1891 to July 1895 Herzl was a correspondent for the Wiener Zeitung Neue Freie Presse in Paris , where political and social problems as well as parliamentary operations aroused his interest. A collection of newspaper articles on the subject appeared in 1895 under the title Das Palais Bourbon (where the French National Assembly is located ). After his experiences in Paris, Herzl initially saw the “ Jewish question ” as a social question that was to be resolved through the organized mass conversion of Jewish youths to the Christian faith. Around 1892/1893 he wrote to Moritz Benedikt that he had no qualms about converting pro forma to Christianity . In this way, he can advance professionally and save his children from discrimination . In 1893 he developed a plan for a mass conversion of Austrian Jews to Catholicism. Robert Wistrich wrote about Herzl's plans that they made it clear that “his own assimilation course was by no means only superficial”.

Herzl later changed his views on converting to Christianity. With his drama Das Ghetto (later renamed Das neue Ghetto ), which he wrote in the autumn of 1894, Herzl hoped to contribute to mutual tolerance between Christians and Jews and to stimulate a public discussion of the Jewish question, which until now had only been dealt with in private conversations was. In his play, Herzl opposes assimilation and conversion as possible solutions to the problem. At the same time he reported on the Dreyfus affair and was also present at the public demotion of Dreyfus on January 5, 1895.

Herzl was an honorary member of the Vienna Kadimah (student association) .

First Zionist activities

As a first practical attempt to realize his Zionist ideas, Herzl met in May 1895 with Baron Maurice de Hirsch , the then leading Jewish philanthropist . Von Hirsch did not even have the opportunity to carry out his plans in detail; this meeting ended completely unsuccessful. Meanwhile, Herzl used his conceptual draft to write down Der Judenstaat , which he finished on June 17, 1895 and published the following year. Another conversation by Herzl about the thoughts expressed in the Jewish state with his friend Emil Schiff, an enlightened Jewish doctor and journalist, also ended unsuccessfully and plunged Herzl into a deep crisis. Herzl had planned, with the help of Moritz Güdemann , the Viennese chief rabbi , to talk to Albert Rothschild , the leading representative of the Viennese branch of the Rothschild family. Schiff was of the opinion, however, that the rabbi would consider Herzl insane and immediately report this to his parents, which would plunge them into deep grief. On June 18, 1895, one day after the end of the Jewish state , Herzl wrote to Baron de Hirsch:

"Dear Sir!

My last letter requires a degree. There you have it: I've given up on the matter ...

The Jews cannot be helped for the time being. If someone showed them the promised land, they would mock him. Because they are depraved.

Still, I know where it is: in us. In our capital, in our work and in the peculiar connection of the two that I have devised. But we have to get even deeper, be insulted, spat at, mocked, beaten, looted and slain even more, until we are ripe for this idea. "

The only one who supported Herzl unreservedly at the time was Max Nordau . Herzl's ideas were rejected not only by Orthodox Jews, for whom Zionism was in contradiction to the messianic promises in Judaism, but also by most of the assimilated Jews in Western Europe (for example, Anton Bettelheim wrote in the Münchner Allgemeine Nachrichten about the “Fasching dream one through columnists hungover the Judenrausch ”).

In the Jewish state , it is essentially about the thesis that the establishment of a Jewish state was necessary and feasible. The motto of the writing is: “We are one people, one people”, which is further elaborated: “The Jewish question is a national question, in order to solve it we must above all make it a world question, which in the council of the Cultural peoples will have to be resolved. ”Herzl then worked as a columnist for the Neue Freie Presse in Vienna - as Daniel Spitzer's successor - and also published in the German-language daily Pester Lloyd from Budapest. In 1901, as editor of the Neue Freie Presse in Vienna, Herzl met the then nineteen-year-old author Stefan Zweig , whose career he promoted.

Zionist organization and congress in Basel

Together with Oskar Marmorek , Max Nordau and David Farbstein, Theodor Herzl organized the first World Zionist Congress (August 29 to 31, 1897) in Basel and was elected President of the World Zionist Organization . The Basel program adopted there formed the basis for numerous negotiations (including with Kaiser Wilhelm II during his visit to Palestine in front of the Jaffator in Jerusalem and the Turkish sultan Abdülhamid II ) with the aim of creating a "home for the Jewish people" in Palestine . Although without any tangible success at the time, Herzl's work created the essential prerequisites for the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. Also in 1897, Herzl published the play Das neue Ghetto and founded Die Welt in Vienna as a monthly information publication for the Zionist movement, which with interruptions up to In 1938 it appeared under Neue Welt and from 1948 it appeared continuously in Vienna under Illustrierte Neue Welt . In 1899 Herzl founded the Jewish Colonial Trust in London , the task of which was to raise and provide money for the purchase of land in Palestine, at that time still part of the Ottoman Empire . On February 27, 1902 Herzl and Zalman David Levontin founded the Anglo-Palestine Company (APC) as a subsidiary, from which Bank Leumi later emerged. Herzl's friend and henchman Jacob Moser , who was one of the most important financial supporters of early Zionism, belonged to both organizations . On the part of Great Britain (more precisely: by the British Colonial Minister Joseph Chamberlain ), Herzl, as the representative of the World Zionist Organization, was offered an area in East Africa. The Uganda program failed on the one hand because most Zionists only saw Palestine as a possible Jewish settlement area; on the other hand, the area was unsuitable.

In 1900 Herzl published the Philosophical Stories . In his utopian novel Altneuland (1902) he created his idealistic picture of a future Jewish state under the motto If you want, it's not a fairy tale . In it he formulated a draft for a political and social order of a Jewish state in Palestine and also took the view that the Arabs living in Palestine would happily welcome the new Jewish settlers. In the Hebrew translation by Nachum Sokolow , the novel was called Tel Aviv , where “ Tel” (ancient settlement mound ) stands for “old” and “Aviv” (spring) for “new”. The naming of the city of Tel Aviv was inspired by Herzl's novel.

Three days before Kaiser Wilhelm II's trip to Palestine , Herzl wrote in his diary:

“To stand under the protectorate of this strong, great, moral, splendidly administered, tightly organized Germany can only have the most beneficial effects for the character of the Jewish people. In one fell swoop we would come to a perfectly orderly internal and external legal situation. "

death

On January 26, 1904, Herzl met Pope Pius X in Rome to ask for his support for his plan to establish a Jewish state in Palestine. Pius X refused this request. He could not prevent the Jews from moving to Palestine, but could never sanction it. Jerusalem be sanctified through Jesus Christ . Since the Jews did not recognize the Christian God and Jesus Christ, as head of the church he could not recognize the Jews either.

In April 1904, doctors diagnosed Herzl with a heart condition. Badly weakened, he went to Franzensbad for a cure . Herzl did not allow himself to be dissuaded from his work, and his health did not improve. At the beginning of June he traveled to Edlach, a district of Reichenau an der Rax , where he felt better for a short time. At the beginning of July he got pneumonia. When Herzl was dying, his sponsor William Hechler was granted privileged access to Herzl. Hechler, Anglican chaplain of the British Embassy in Vienna, conveyed Herzl's farewell words to the Zionist movement: “Greet all of you for me, and tell you that I have given my heart-blood for my people.” Herzl said to his doctor: “It are splendid, good people, my fellow citizens! You will see, they will move into their homeland! ”Theodor Herzl died in the late afternoon of July 3, 1904 in the Edlach hydrotherapy institute founded by his doctor, Albert Konried (1867–1918); he was buried in the Dobling cemetery at his father's side. David Wolffsohn , Herzl's successor as President of the World Zionist Organization, gave a short eulogy.

On August 14, 1949, the coffins of Theodor Herzl and his parents were laid out in the Vienna City Temple before they were transferred . They were then taken to Jerusalem and buried on Mount Herzl in West Jerusalem. Herzl had ordered this transfer in his will as soon as the great goal of establishing a Jewish state had been achieved. The Israeli authorities had ignored his wish to be buried in the cemetery on Mount Carmel near Haifa (which he expressly requested at the 4th Zionist Congress in London in 1900).

In 2006 the remains of his two children Pauline and Hans were transferred from Bordeaux and buried next to their father. The youngest daughter, Margarete ("Trude"), as a victim of the Holocaust, has no grave. Herzl's only grandson, Stefan Theodor Norman Neumann, was buried on Herzlberg in December 2007, 61 years after he had committed suicide in Washington, DC , when he learned of his parents' death in the Holocaust.

Effect, appreciation

Herzl was the founder of political Zionism. The movement he started became the most vital force in modern Jewish history. He founded her press organ Die Welt , the Jewish Colonial Trust as the financial basis and the institution of the Zionist Congress as the embodiment of parliamentarism in this global movement. His predictions came true: in 1948 the State of Israel was founded.

Herzl's funeral on July 7, 1904, described Stefan Zweig:

“Because suddenly people came to every train station in the city, with every train day and night from all kingdoms and countries, western, eastern, Russian, Turkish Jews, from all provinces and small towns suddenly stormed them, the horror of the news still in the face; One never felt more clearly what used to make the arguments and talk invisible, that it was the leader of a great movement who was being buried here. It was an endless train. Suddenly Vienna noticed that not only a writer or middle poet had died here, but also one of those creators of ideas that only emerge victoriously in a country or in a people at tremendous intervals. There was a commotion at the cemetery; too many suddenly streamed to his coffin, weeping, howling, screaming in a wildly exploding despair, it became a rage, almost a rage; all order was broken by a kind of elemental and ecstatic mourning such as I had never seen before or after at a funeral. And from this tremendous pain, which rushed up from the depths of a whole million people, I was able for the first time to measure how much passion and hope this single and lonely person thrown into the world through the force of his thoughts. "

After Herzl's death, Max Nordau concluded his speech at the 7th Zionist Congress in Basel in 1905 with the words:

- Eternally in the people's memory

Live your work and live your image.

Look! we

faithfully guard your legacy , the proud shield of David.

In the folds of the flag of Zion

your coffin will one day be wrapped.

What you swore, we will keep it,

and your longing will be fulfilled ...

Hugo Zuckermann wrote a rhapsody dedicated to Herzl , which was published in the Vienna Jewish newspaper in 1915 .

The city of Herzlia , founded in 1924 in what is now Israel , was named after Theodor Herzl.

Honors

- Honorary grave on the Herzlberg named after him in Jerusalem

- On November 23, 1924, the city of Herzlia was named after Theodor Herzl

- Theodor Herzl Museum inside the Herzlberg cemetery

- Theodor Herzl Prize (Literature Prize)

- Theodor Herzl lecturer at the University of Vienna

- Very large mosaic with the portrait of Theodor Herzl in the Rathenauplatz underground station in Nuremberg

- Theodor Herzl (ship)

Graves in Vienna and Jerusalem

Herzl's first resting place in the Döblinger Friedhof

The grave on Herzlberg

Fonts

- The Jewish state. Attempt at a modern solution to the Jewish question. , Leipzig and Vienna 1896; Wikisource full text ; Digitized and full text in the German Text Archive , Der Judenstaat. or e-book from the Vienna University Library ( eBooks on Demand ), Manesse-Verlag Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-7175-4055-6 .

- Philosophical narratives. , Berlin 1900, collection of 17 feature articles from the years 1887–1900: Wikisource full text . New edition ed. v. Carsten Schmidt, 2011, Lexikus Verlag, ISBN 978-3-940206-29-9 .

- Old new land. Utopian novel, Leipzig 1902, haGalil full text .

- Letters and diaries. 7 volumes edited by Alex Bein , Hermann Greive , Moshe Schaerf and Julius H. Schoeps . Propylaea, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1983–96.

literature

Biographies

in order of appearance

- Adolf Friedemann: The Life of Theodor Herzl. Jewish publishing house, Berlin 1914.

- Reuben Brainin : The life of Herzl. New York 1919. (Original Hebrew 1898: Chaje Herzl. Describes Herzl's life up to the first Congress.)

- Leon Kellner : Theodor Herzl's apprenticeship years 1860–1895. According to the handwritten sources. Löwit, Vienna / Berlin 1920 (the first part of a biography planned in two volumes; the second part never came about).

- Alex Bein : Theodor Herzl. Biography. Fiba, Vienna 1934 (fundamental; various subsequent editions, translated into several languages).

- Josef Patai: Herzl. Omanuth, Tel Aviv 1936 (with 110 illustrations).

- Amos Elon : Tomorrow in Jerusalem. Theodor Herzl, his life and work. Molden, Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-217-00546-5 .

- Julius Hans Schoeps : Theodor Herzl. Pioneer of political Zionism (= Personality and History , Volume 86). Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen 1975, ISBN 3-7881-0086-9 .

- Ernst Pinchas Blumenthal: Servant at the light. A biography of Theodor Herzl. European Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-434-00346-0 .

- Amos Elon: Theodor Herzl. Schocken Books, New York 1986, ISBN 0-8052-0790-2 .

- Avner Falk : Herzl, King of the Jews. A Psychoanalytic Biography of Theodor Herzl. University Press of America, Lanham 1993, ISBN 0-8191-8925-1 .

- Jacques Kornberg: Theodor Herzl. From Assimilation to Zionism. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1993, ISBN 0-253-33203-6 .

- Julius H. Schoeps: Theodor Herzl 1860-1904. If you want, it's not a fairy tale. A text-picture monograph. With 350 illustrations in duotone, Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-95447-556-X

- Serge-Allain Rozenblum: Theodor Herzl. Éditions du Félin, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-86645-337-9 .

- Shlomo Avineri : Theodor Herzl and the founding of the Jewish state . Jewish publishing house in Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-633-54275-8 .

Articles in biographical manuals

- Robert Weltsch : Herzl, Theodor. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 8, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1969, ISBN 3-428-00189-3 , pp. 735-737 ( digitized version ).

- Helge Dvorak: Biographical Lexicon of the German Burschenschaft. Volume I: Politicians. Sub-Volume 2: F-H. Winter, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-8253-0809-X , pp. 317-318.

Individual points of view

- Tulo Nussenblatt (ed.): Contemporaries about Herzl. Jewish book and art publisher, Brno 1929.

- Saul Raphael Landau : Sturm und Drang in Zionism. Review of a Zionist. Before, with and around - Theodor Herzl. Publishing house of the Neue National-Zeitung, Vienna 1937.

- Hermann and Bessie Ellern: Herzl, Hechler, the Grand Duke of Baden and the German Emperor. Ellern's Bank, Tel Aviv 1961.

- Clemens Peck: In the laboratory of utopia. Theodor Herzl and the “Altneuland” project. Jewish publishing house, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-633-54262-8 .

- Doron Rabinovici , Natan Sznaider : Herzl relo @ ded - No fairy tale . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-633-54276-5 .

- Peter Rohrbacher: "Wüstenwanderer" versus "Wolkenpolitiker" - The press feud between Eduard Glaser and Theodor Herzl in: Anzeiger der philosophisch-historical Klasse ; 141. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences (2006), 103–116.

Essays

- Isaiah Friedman: Theodor Herzl - Political Activity and Achievements . In: Israel Studies , Vol. 9 (2004), No. 3, pp. 46–79.

- Andrea Livnat: The Prophet of the State. Theodor Herzl in the collective memory of Israel. In: jungle-world.com (excerpt).

Periodicals

- Herzl Year Book . New York 1958 ff.

Web links

- Literature by and about Theodor Herzl in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Theodor Herzl in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Theodor Herzl in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Works by Theodor Herzl in Project Gutenberg ( currently usually not available for users from Germany )

- Works by Theodor Herzl in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Works by Theodor Herzl at Zeno.org .

- Susanne Eckelmann: Theodor Herzl. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Works by and about Theodor Herzl at Open Library

- The Herzl Family Website ( Memento from December 19, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- aGalil: Theodor Herzl and Zionism ( Memento from June 6, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- “ Don't do anything stupid while I'm dead ” Portrait documentation about Theodor Herzl on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his death; by Ludger Heid for Die Zeit on June 24, 2004 (6 subpages)

- J. Tobias on haGalil

- On the rejection of a Jewish state by “Neturei Karta”, a fundamentally radical splinter group of ultra-orthodoxy

- Benjamin Rosendahl: Theodor Herzl - central figure of Zionism? , 1998

- The Palais Bourbon , Leipzig 1895, digitized version of the Vienna University Library

- Jüdische Allgemeine about Andrea Livnat's Herzl study

- Herzl and Zionism on www.mfa.gov.il

- Kalmar Zoltán: Theodor Herzl's National Answer to the Misery of the Jewish People

- Theodor Herzl's Diaries 1895–1904 , Volume I, Jüdischer Verlag, Berlin, 1922

- Theodor Herzl's Diaries 1895–1904, Volume II, Jüdischer Verlag, Berlin, 1923

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Brenner : History of Zionism , Beck, Munich 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Ernst Pawel: The Labyrinth of Exile - A Life of Theodor Herzl , Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 1989, ISBN 0-374-52351-7 , p. 5.

- ^ Ernst Pawel: The Labyrinth of Exile - A Life of Theodor Herzl , Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 1989, ISBN 0-374-52351-7 , p. 9.

- ↑ Julius Hans Schoeps: Theodor Herzl, 1860-1904 - If you want, it's not a fairy tale , C. Brandstätter, 1995, p. 13.

- ^ Ernst Pawel: The Labyrinth of Exile - A Life of Theodor Herzl , Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 1989, ISBN 0-374-52351-7 , p. 11.

- ^ Jacques Kornberg: Theodor Herzl - From Assimilation to Zionism. In: Jewish Literature and Culture , Indiana University Press, 1st edition, 1993, pp. 13 f.

- ^ Israel Cohen: Theodor Herzl - Founder of Political Zionism , Thomas Yoseloff, London / New York, 1959, p. 30.

- ^ Jacques Kornberg: Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism . Indiana University Press 1993. ISBN 0253332036 , pp. 50 f.

- ^ J. Kauffmann: Yearbook of the Jewish-Literary Society , Vol. XVII, Frankfurt a. M., 1926, p. 34.

- ↑ Ilse Sternberger: Princes without a Home. Modern Zionism and the Strange Fate of Theodor Herzl's Children 1900–1945. San Francisco 1994.

- ^ Entry for Margarete Neumann in the victim database of the DÖW .

- ^ Entry for Margarete Neumann in The Central Database of Shoah Victims' Names .

- ^ Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : Public Criticism of National Socialism in the Greater German Reich. Life and worldview of the Viennese Baptist pastor Arnold Köster (1896–1960) (= historical-theological studies of the 19th and 20th centuries; 9). Neukirchen-Vluyn 2001, p. 35 f.

- ^ Jacques Kornberg: Theodor Herzl - From Assimilation to Zionism , Indiana University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-253-33203-6 , p. 2.

- ↑ Harald Seewann (ed.): Theodor Herzl and the academic youth. A collection of sources on Herzl's references to corporation students , Graz 1998.

- ↑ Gerald Stourzh: Traces of an Intellectual Journey - Three Essays , Böhlau Verlag, 2009, pp. 61 and 62.

- ^ Robert S. Wistrich: Socialism and the Jews - The Dilemmas of Assimilation in Germany and Austria , Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, London, 1982, p. 212.

- ↑ Gregor Gatscher-Riedl: "The ribbon of freedom wraps itself around Juda's noble remains" - On the history of the colorful Viennese Zionist student associations (2017)

- ^ Theodor Herzl: Letters and Diaries. Fourth volume: Letters 1895–1898. Propylaea, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-549-07633-9 , p. 54.

- ↑ Theodor Herzl: Zionism is the return home to Judaism before the return to the Jewish land . In: Gerhard Jelinek : Speeches that changed the world . dtv, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-423-34700-6 , p. 78 f.

- ↑ See JCG Röhl: Wilhelm's strange crusade. A hundred years ago the German Kaiser met the Zionist Theodor Herzl in the desert sand (series Zeitllauf ). In: The time . October 8, 1998.

- ^ Anton Pelinka , Robert S. Wistrich: Changes and breaks. From Herzl's World to the Illustrated New World. 1897-1997. Edited by Joanna Nittenberg, Edition INW, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3950035613 .

- ^ Shlomo Avineri, Zionism According to Theodor Herzl , in Haaretz (December 20, 2002). [1]

- ↑ THEODOR HERZL MEETS POPE PIUS X at www.bunyanministries.org

- ↑ The Life of Theodor Herzel at lexikus.de , accessed on January 24, 2012.

- ↑ Alex Bein : Theodor Herzl. Vienna 1934, p. 684.

- ↑ Daily news. (...) deaths. In: Pester Lloyd , Abendblatt, No. 150/1904, July 4, 1904, p. 2 ( unpaginated ). (Online at ANNO ). .

- ^ Max Nordau: Zionist writings. Jüdischer Verlag, Berlin 1923. Quoted from: Theodor Herzl. A memorial book for the 25th anniversary of death . Jüdischer Verlag, Berlin 1929, p. 18.

Remarks

- ↑ Both to correspondents with whom he was on “you” and to those with whom he was married.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica , Second Edition, Volume 9, p. 66. - After the conclusion of the first congress, Herzl wrote the memorable (and prophetically correct) words in his diary (September 3, 1897, Vienna): “I can sum up the Basel Congress in one word together - which I will take care not to speak out in public - so it is this: in Basel I founded the Jewish state. If I said this out loud today, I would be greeted with universal laughter. Maybe in five years, at least in fifty, everyone will see it. "

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Herzl, Theodor |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Herzl, Mattitjahu (Hebrew first name); Benjamin Seff (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian writer, publicist, journalist and Zionist politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 2, 1860 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Plague (city) |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 3, 1904 |

| Place of death | Edlach, municipality of Reichenau an der Rax , Lower Austria |