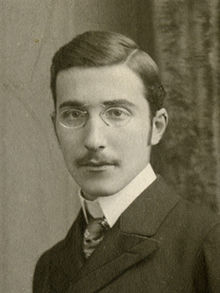

Stefan Zweig

Stefan Zweig ( November 28, 1881 in Vienna – February 23, 1942 in Petrópolis , Rio de Janeiro State , Brazil ) was a British -Austrian writer , translator and pacifist .

Zweig was one of the most popular German-language writers of his time. With his widely read realist-style psychological novellas such as Burning Secret (1911), Fear , Letter from an Unknown Woman , Amok and literary biographies, including Magellan. The man and his deed and triumph or tragedy of Erasmus of Rotterdamhe was one of the most important German-speaking storytellers at the beginning of the 20th century. His language is characterized by a high degree of vividness and a pleasing tonality, but the works are largely committed to the novelistic realism in their narrative style and stylistic means. Not least due to the combination of classic elements, including the dramatic course of action, with a psychoanalytically motivated character drawing and stylistic multi-perspectivity, Zweig offered his broad readership authentic access to a literature in which its present was reflected without confronting it with modernist narrative styles.

Among his numerous prose works, the chess novella , the great moments of mankind and his memoirs Die Welt von Gestern stand out.

Life

1881 to 1918 - Early years

Stefan Samuel Zweig was a son of the wealthy Jewish textile entrepreneur Mori(t)z Zweig (1845-1926) and his wife Ida Brettauer (1854-1938), daughter of a wealthy merchant/banker family originally from Hohenems , born and raised in Italian Ancona , where her family had emigrated. He was born in Vienna in the upper-class apartment at Schottenring 14 and grew up with his brother Alfred at Concordiaplatz 1, later at Rathausstrasse 17 in the city center. The head office of his father's weaving factory was located at Schottenring 32 (site of the later Ringturm ), then at Franz-Josefs-Kai 33 (block of buildings of the Hotel Métropole ). The Zweig family was not religious, and Zweig later described himself as a “Jew by chance”. He is not related to the German writer Arnold Zweig .

In 1899 he graduated from the Viennese Gymnasium Wasagasse . Then, enrolled at the University of Vienna as a student of philosophy, he avoided lecturing as much as possible and preferred to write for the feuilleton of the Neue Freie Presse , of which Theodor Herzl was the editor. After his poems had already been published in magazines from 1897, the volume of poems Silberne Saiten was published in 1901 and in 1904 his first novella , Die Liebe der Erika Ewald . In that year, Stefan Zweig received his doctorate with a dissertation on the philosophy of Hippolyte Taine from Friedrich Jodl in Vienna . phil. PhD . Gradually he developed a striking style of writing that combined careful psychological interpretation with captivating narrative power and brilliant style . In addition to his own stories and essays, Zweig also worked as a journalist and as a translator of the works of Verlaine , Baudelaire and especially Émile Verhaeren . His books were published by Insel-Verlag in Leipzig , with whose publisher Anton Kippenberg he eventually became friends and to whom he inspired the Insel-Bücherei , founded in 1912 , which quickly established itself on the book market with very large sales figures and is still published today .

After Donald A. Prater , Oliver Matuschek and Benno Geiger had pointed out a pre-1920 tendency towards exhibitionism by Zweig , the journalist and literary scholar Ulrich Weinzierl , in his 2015 book Stefan Zweig's burning secret , sees the statements of Zweig's former friend Benno Geiger ("Er suffered from an addiction to exhibitionism, that is, from an irresistible urge to expose himself in the presence of a young girl"). From 1912 onwards, Weinzierl finds in Zweig's records clear indications of what he called "show pillorying" and cryptic hints that he had almost been caught in Schönbornpark . The Germanist Weinzierl sees psychodynamic mechanisms in this tendency, which threatened Zweig's bourgeois existence, which would have driven Zweig from an artistic point of view. According to the Bonn psychiatrist, forensic psychiatrist and medical historian Dieckhöfer, the phenomenon of exhibitionism for the poet Zweig became “ultimately as a fleeting transitional syndrome of character maturation” “in the midst of a culturally hostile to sex and body environment”, whereby “a healthy weal and woe finally emerged “ prevailed.

Zweig lived an upper-class lifestyle and traveled extensively. Thus, on the advice of Walther Rathenau , he visited British India (with Calcutta , Benares , Gwalior , Rangoon in Burma ) and British Ceylon for five months in November 1908 , and America in February 1911 . These trips brought him into contact with other writers and artists, with whom he often had long-lasting correspondence. Zweig was also a keen and professionally recognized collector of autographs .

At the outbreak of the First World War , as he writes in The World of Yesterday :

"... for the time being no military duties, since I had been declared unfit for all assignments ... On the other hand, it was unbearable to wait at such a time as a relatively young person until he was scraped out of his darkness and thrown somewhere where he could be didn't belong. So I looked around for a job where I could at least do something without being inflammatory, and the fact that a friend of mine, a senior officer, was in the War Archives enabled me to get a job there.”

It was possible to request Rainer Maria Rilke at the age of "almost forty" "also for our remote war archives ... he was soon released thanks to a kind medical examination".

Zweig now decided, also under the influence of one of his friends, the French pacifist Romain Rolland , "to begin my personal war: the fight against the betrayal of reason to the current mass passion". He described what he felt during this time:

"From the beginning I did not believe in 'victory' and knew only one thing for sure: that even if it could be won at immeasurable sacrifices, it would not justify those sacrifices. But I was always alone among all my friends with such a reminder, and the confused howl of victory before the first shot, the division of booty before the first battle often made me doubt whether I myself was insane among all these clever ones or rather alone horribly awake in the midst of their drunkenness .”

In 1917 he was first suspended from military service and later dismissed entirely. The preparation of the performance of his tragedy "Jeremias" at the Stadttheater gave Zweig the opportunity to move to Zurich . Here in neutral Switzerland he also worked as a correspondent for the Wiener Neue Freie Presse and published his humanistic opinion, which was completely unrelated to party and power-political interests, in the German-language newspaper Pester Lloyd . In Switzerland in 1918 he met Erwin Rieger , who later published the first biography of Zweig.

1919 to 1933 – Salzburg years

After the end of the war, Zweig returned to Austria. Coincidentally, he entered on March 24, 1919, the same day that the last Austrian emperor, Charles I , left for exile in Switzerland. Zweig later described this encounter on the frontier in his work The World of Yesterday .

Zweig went to Salzburg , where he had bought the desolate Paschinger Schlössl on the Kapuzinerberg in 1917 during the war, in order to live in it later. In January 1920 he married Friderike Winternitz , divorced from the journalist Felix Winternitz, who brought two daughters into the marriage.

Under the impression of increasing inflation in Germany and Austria, which would presumably make it extremely difficult to import foreign books into German-speaking countries for reading in the original version in the long term, Zweig advised the publisher of the Leipzig Insel Verlag, Anton Kippenberg, to publish foreign-language literature in the original languages as "Orbis Literarum", which should consist of the series Bibliotheca Mundi , Libri Librorum and series Pandora . However, all three series remained well below the expected sales figures and ended after just a few years.

As a committed intellectual , Stefan Zweig vehemently opposed nationalism and revanchism and promoted the idea of a spiritually united Europe . In the 1920s he wrote a lot: short stories, dramas, short stories. The collection of historical snapshots , Great Moments of Mankind from 1927, is still one of his most successful books.

In 1928, Stefan Zweig toured the Soviet Union , where his books were published in Russian at the instigation of Maxim Gorky , with whom he corresponded. He dedicated his 1931 book The Healing by the Spirit to Albert Einstein . In 1933, Zweig wrote the libretto for the opera The Silent Woman by Richard Strauss .

1934 to 1942 – years of exile

After the National Socialists “ seized power ” in the German Reich in 1933, their influence was also felt in Austria in the form of bombing terror and overt appearances by the SA . The Christian Socialists defended themselves against the National Socialists - for example by banning the NSDAP after a hand grenade attack on Christian-German military gymnasts . Previously, they had abolished democracy in order to be able to eliminate the Social Democrats (see Parliament's self- elimination ); Zweig took the National Socialist threat from Salzburg, almost within sight of Hitler's domicile on the Obersalzberg , very seriously and saw it as a "prelude [to] much more far-reaching interventions".

On February 18, 1934, a few days after the February uprising of the Social Democrats against the Austro-Fascist corporate state , four police officers searched the house of the declared pacifist Stefan Zweig, because he had been denounced that there were weapons from the Republican Protection League in his house . Although Zweig realized that the search was only carried out pro forma, he was deeply affected by it, boarded the train two days later and emigrated to London .

In the German Reich, his books were no longer allowed to be published by Insel Verlag , but were published by Herbert-Reichner-Verlag Wien , which Zweig also supported as a literary advisor during these years. Nevertheless, contacts with Germany did not break off. He also made a trip to South America . In March 1933 the film adaptation of his novella Burning Secret was released in cinemas. Since the title offered much cause for ridicule in view of the Reichstag fire , the further showing of the film was banned. For Richard Strauss he was able to write the libretto for the opera The Silent Woman ; the opera was performed at the Dresden Opera on the basis of Adolf Hitler's personal approval , but then had to be canceled because of the Jewish author. Zweig was placed on the book burning list and was added to the banned authors list in 1935. In the Austrian corporative state he was still very much appreciated, while in Nazi Germany he was considered "undesirable". His Reich German publisher, Anton Kippenberg from Insel Verlag, had to part with his most successful author. Living in exile in England, Zweig was still able to reach a German-speaking audience through the Reichner publishing house in Vienna; after the annexation of Austria to the German Reich, his German writings were printed in Sweden , and he remained one of the most widely read authors of his time internationally.

His marriage to Friderike Zweig, from whom he lived partially separated after his escape from Salzburg in 1934, was dissolved in London in November 1938. He had entered into a liaison with his secretary, Charlotte Altmann (1908–1942), who came from a Jewish family of manufacturers, and his wife was aware of this. In 1939 he married Charlotte Altmann, who had followed him on his travels. The contact with his first wife never broke off, he remained in close contact with letters until his death, and there were also various personal encounters.

At the beginning of the Second World War , Stefan Zweig took British citizenship . He moved with his wife from London to Bath in July 1939 and bought a house there (on the corner of Lyncombe Hill and Rosemount). Here he began work on the biography on Honoré de Balzac . After his death, he gave a farewell speech to his friend Sigmund Freud at the funeral service on September 26, 1939 in Golder's Green crematorium in London, which was published under the title Words on Sigmund Freud's coffin . But he soon left Britain , fearing that the English might fail to distinguish between Austrians and Germans and then interne him as an " enemy alien ". In 1940, via stops in New York , Argentina and Paraguay , he finally arrived in Brazil , a country that had previously given him a triumphant welcome and for which he held permanent entry permits. According to Zweig biographer Alberto Dines , as a celebrity despite the anti-Semitism of the Getúlio Vargas dictatorship , Zweig was granted this permanent visa in exchange for writing a book benefiting Brazil.

In 1941 the monograph Brazil was published. The 1941 revocation of the doctorate by the National Socialists was declared null and void by a Senate resolution of the University of Vienna on April 10, 2003, after all those involved in the revocation had already died.

death

On the night of February 22-23, 1942, Stefan Zweig committed suicide in Petrópolis in the mountains about 50 kilometers northeast of Rio de Janeiro with an overdose of Veronal . Depressive states accompanied him for years. The death certificate lists the time of death as 12:30 p.m. on February 23, 1942 and the cause of death as “taking poison – suicide”. His wife Lotte followed Zweig to her death. Domestic workers found both of them in their bed around 4 p.m.: him lying on his back with his hands clasped, she leaning against his side.

In his farewell letter, Zweig wrote that he would retire “of his own free will and with clear mind”. The destruction of his "spiritual homeland Europe" had uprooted him for his feeling that his strength was "exhausted by long years of homeless wandering". Zweig's decision to end his life was not met with sympathy from everyone, especially since his material existence, unlike that of many fellow writers in exile , was secure. Stefan Zweig became a symbol for intellectuals fleeing tyranny in the 20th century. With this in mind, the Casa Stefan Zweig was set up in his last house in Petrópolis , a museum that is not only intended to preserve the memory of his work.

In 1952, on the tenth anniversary of Zweig's death, Thomas Mann wrote about his pacifism: "There were times when his radical, unconditional pacifism tormented me. He seemed ready to allow evil to rule, if only war, which he hated above all else, could be avoided. The problem is unsolvable. But since we learned how even a good war produces nothing but evil, I think differently about his attitude then – or try to think differently about it.”

As strictly as Stefan Zweig demanded a complete separation of spirit and politics, he stood up for a united Europe in the tradition of Henri Barbusse , Romain Rolland and Émile Verhaeren .

In 2017 he was posthumously honored by the Brazilian government with the highest order for foreigners, the Ordem Nacional do Cruzeiro do Sul , the National Order of the Southern Cross , with the rank of Commander ( Comendador ). The Austrian Ambassador accepted the award in his place at Casa Stefan Zweig in Petrópolis. In previous years, a street in Rio's Laranjeiras neighborhood , Rua Stefan Zweig, where members of the upper middle class have houses, was named after him. Streets were also named after him in São Paulo and a city in the northern periphery. In addition, an Escola Estadual in the Vila Ivone district in the southeast of São Paulo bears his name. Since 2014, the Salzburg University of Education has been named Stefan Zweig.

Impact and characteristics of the work

In particular, Zweig's prose works and novel-like biographies ( Joseph Fouché , Marie-Antoinette ) still find an audience today. The entire work is characterized by a high density of novellas ( chess novella , the amok runner , etc.) and historically based narratives. Historical personalities from Ferdinand Magellan to Lew Tolstoy , Fyodor Dostoyevsky , Napoleon Bonaparte , Georg Friedrich Handel and Joseph Fouché to Marie-Antoinette find their way into Zweig's work in a strongly subjectively personalized story.

If one reduced Zweig's work to four dominant characteristics, one would probably describe it with the terms tragedy, drama, melancholy and resignation. Almost all of Zweig's works end in tragic resignation. The protagonist is prevented by external and internal circumstances from attaining happiness, which seems immediately attainable, which makes it all the more tragic. This feature is particularly prominent in the novel Impatience of the Heart , which is Zweig's only completed novel. In the exemplary novella The Amokrunner , a typology of passion, inspired by great role models such as Balzac and thereby entirely following the storytelling tradition of the Viennese School - especially Arthur Schnitzler - the main character is subjected to a demonic compulsion that throws her out of the traditional order of her life tears. The influence of Sigmund Freud is clearly recognizable here. This novella, like all of Zweig's other novellas, describes an outrageous event , which according to Goethe is a genre-specific feature of the novella.

In the Schachnovelle , Zweig's best-known book, bourgeois humanity struggles against the brutality of an alienated world. A coldly calculating, robotic world chess champion, driven by vulgar greed, plays against a man held in solitary confinement by the Nazis. On the one hand, man is confronted with an inhuman system ( fascism ), on the other hand, Zweig describes the suffering of the prisoner without the possibility of contact with the outside world. Despite this haunting plea for humanity, Zweig denied the writer any political role. Against the background of the Second World War, this point of view differentiated and divided him from the other literary figures in exile (mainly Heinrich Mann and Ernst Weiß ) and the PEN Club .

Stefan Zweig saw the unification of Europe as the only way to avert future danger of war and nationalism. In particular, his supranational European unification model has an anti-political and anti-economic dimension in the sense of a humanistic universalism of the supranational Habsburg monarchy. Zweig's links to the idea of the Habsburg monarchy were criticized as a detached perspective, especially shortly after the Second World War. Nevertheless, branch like Joseph Roth , but also James Joyce saw the Central European period before the First World War as a counterpart to the Prussian-North German uncompromising world view and emphasized the people-uniting and balancing Habsburg principles of "Live and let live!".

factories

original editions

Complete bibliography of first editions at Wikisource

- silver strings poems. 1901

- The Philosophy of Hippolyte Taine . Dissertation, 1904

- The love of Erika Ewald . novellas. book decoration v. Hugo Steiner-Prag, Fleischel & Co., Berlin 1904

- The early wreaths. poems. Island, Leipzig 1906

- Tersites. A tragedy. In three acts, Leipzig 1907

- Emile Verhaeren . Leipzig 1910

- Burning Mystery , 1911

- first experience. Four stories from Kinderland: Story in the twilight. The Governess . Burning Secret. summer novelette. , Insel, Leipzig 1911

- The house by the sea. A play in two parts. (In three acts) Leipzig 1912

- The transformed comedian. A game from German Rococo. Leipzig 1913

- Foreword to Max Brod's novel Tycho Brahe's Path to God. Leipzig 1915

- Jeremiah. A dramatic poem in nine scenes. Leipzig 1917

- Memoirs of Emile Verhaeren , privately printed 1917

- The heart of Europe. A visit to the Geneva Red Cross . Cover drawing by Frans Masereel , Rascher, Zurich 1918

- legend of a life. A chamber play in three acts. Island, Leipzig 1919

- rides. landscapes and cities. Tal, Leipzig and Vienna 1919

- Three Masters: Balzac - Dickens - Dostoyevsky . (= The master builders of the world. Attempt at a typology of the mind, volume 1), Insel, Leipzig 1920

- Marceline Desbordes-Valmore . The life of a poet. With transfers by Gisela Etzel-Kühn, Leipzig 1920

- The force. A novella , Insel, Leipzig 1920

- Romain Rolland. The man and the work. Rütten & Loening, Frankfurt 1921

- Letter from a stranger . Lehmann & Schulze, Dresden 1922

- amok . Novellas of a Passion . Island, Leipzig 1922

- The eyes of the eternal brother. A legend . Leipzig 1922 ( Insel Library 349/1)

- Fantastic night . Narrative. The New Review . Born 33. Berlin 1922

- Frans Masereel (with Arthur Holitscher ), Axel Juncker, Berlin 1923

- The Collected Poems . Island, Leipzig 1924

- The Monotonization of the World . Essay. Berlin Stock Exchange Courier , February 1, 1925

- fear . novella. With afterword by EH Rainalter, Reclam, Leipzig 1925

- The fight with the demon. Holderlin - Kleist - Nietzsche . (= The Master Builders of the World, Volume 2), Insel, Leipzig 1925

- Ben Johnson's " Volpone ". A loveless comedy in three acts. Edited freely by Stefan Zweig. With six pictures after Aubrey Beardsley , Kiepenheuer, Potsdam 1926

- The fugitive. Episode from Lake Geneva . Book lottery, Leipzig 1927

- Farewell to Rilke. A speech. Wunderlich, Tubingen 1927

- confusion of feelings. Three novellas. ( Twenty-four hours from the life of a woman , a heart sinking , confusion of feelings ) Insel, Leipzig 1927

- great moments of mankind . Five historical miniatures. Leipzig n.d. (1927, Insel-Bücherei 165/2)

- Three poets of their lives. Casanova - Stendhal - Tolstoy . (= The Master Builders of the World, Volume 3), Insel, Leipzig 1928

- Rachel argues with God . In: Insel-Almanach on the year 1929, pp. 112-131, Insel, Leipzig 1928

- Joseph Fouche . Portrait of a political man. Island, Leipzig 1929

- The poor man's lamb. Tragedy in three acts. (nine pictures), Insel, Leipzig 1929

- Four stories. (The Invisible Collection. Lake Geneva Episode. Leporella . Buchmendel ). Insel, Leipzig 1929 (insel library 408/1)

- The Healing of the Spirit . Mesmer - Mary Baker Eddy - Freud . Leipzig 1931

- Sigmund Freud . Librairie Stock, Paris 1932

- Marie Antoinette. Portrait of a middle character. Leipzig 1932; Filmed in 1938 by W. S. Van Dyke ( Marie-Antoinette )

- Marie Antoinette The Portrait of an Average Woman. The Viking Press, New York 1933

- Triumph and Tragedy of Erasmus of Rotterdam . Herbert Reichner, Vienna 1934

- The silent woman . Comic opera in three acts. Libretto loosely adapted from Ben Jonson 's comedy Epicoene, or The Silent Woman . Music by Richard Strauss . Fürstner, Berlin 1935. Premiere June 24, 1935 Dresden ( State Opera )

- Mary Stuart. Reichner, Vienna 1935

- Collected Stories , 2 volumes (Volume 1: The Chain , Volume 2: Kaleidoscope ), Vienna 1936

- Castellio versus Calvin or. A conscience against violence , Vienna 1936

- The buried candlestick. novella. Vienna 1937 (describes the menorah on the way from Rome to Constantinople and Jerusalem).

- Encounters with people, books, cities , Vienna 1937

- Magellan. The man and his deed . Vienna 1938

- impatience of the heart . Novel. Bermann-Fischer/Allert de Lange, Stockholm/Amsterdam 1939

- Brazil. A country of the future . Bermann-Fischer, Stockholm 1941

- chess novella . Buenos Aires 1942

- The World of Yesterday . Memoirs of a European. Stockholm 1942

- Montaigne 1942 (essay/fragment about Michel de Montaigne )

- time and world. Collected essays and lectures 1904-1940. (including The Secret of Artistic Creation 1938 London) Bermann-Fischer, Stockholm 1943

- Amerigo. The Story of a Historical Error . Stockholm 1944

- Legends Stockholm 1945

- Balzac. novel of his life. Ed. Richard Friedenthal , Stockholm 1946

- Fragment of a novella. Edited by Erich Fitzenbauer. With 4 original lithographs by Hans Fronius, Vienna 1961

- intoxication of transformation . Novel. From the estate ed. v. Knut Beck 1982

Selection of recent editions

- Adam Lux . Ten Pictures from the Life of a German Revolutionary . With essays and materials. Contributions by Franz Dumont and Erwin Rotermund, Logo, 2005, ISBN 978-3-9803087-7-9 .

- Selected works in four volumes (in cassette), S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 978-3-596-15995-6 .

- Brazil – A Country of the Future . Insel Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-458-35908-1 .

- Clarissa. A Draft Novel . From the estate ed. and edit v. Knut Beck, S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 978-3-10-097080-0 .

- The Lamb of the Poor and Other Dramas . edited by Knut Beck, S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 978-3-10-097066-4 .

- I know the magic of writing . Catalog and history of the Stefan Zweig autograph collection. With annotated reprint of Stefan Zweig's essays on collecting manuscripts. edit of Oliver Matuschek, Inlibris, Vienna 2005, ISBN 978-3-9501809-1-6 .

- intoxication of transformation. Roman from the estate , S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 978-3-596-25874-1 .

- diaries . edited by Knut Beck, S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 978-3-10-097068-8 .

- confusion of feelings. Tales (includes Der Stern über dem Walde ), S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 978-3-596-25790-4 .

- The World of Yesterday . Memoirs of a European , Insel, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-458-35907-4 .

- master novellas . Collection: Burning Secret , The Gunman , Letter from an Unknown Woman , The Woman and the Landscape , Emotional Confusion , Twenty-Four Hours in a Woman's Life , Episode on Lake Geneva , The Invisible Collection , Chess Novella , S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 978-3-596-14991-9 .

- Burning Secret. tales . Collection: Burning secret , scarlet fever , letter from a stranger , Prater spring , two lonely ones , resistance to reality , was it him? , A person not to be forgotten , Unexpected acquaintance with a craft , S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 978-3-10-097070-1 .

- The Moonlight Alley. Collected stories (Burning secret. Story in the twilight. Fear. The gunman. Letter from an unknown woman. The woman and the landscape. The moonlight alley . Fantastic night. Fall of a heart. Confusion of feelings. Twenty-four hours from the life of a woman. Buchmendel. Leporella. The Equal-Unequal Sisters. Chess Novella). Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1989 (Fischer Paperback 9518), ISBN 3-596-29518-1 .

- impatience of the heart . Insel, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-458-35903-6 .

- Snow Winter: 50 Timeless Poems . Martin Werhand Verlag, Melsbach 2016, ISBN 978-3-943910-73-5 .

- Buchmendel & The Invisible Collection . Topalian & Milani Verlag, Ulm 2016, ISBN 978-3-946423-05-8 .

- Stefan Zweig - a unidade spiritual do mundo. The spiritual unity of the world. Conferência proferida no Rio de Janeiro em agosto de 1936. Casa Stefan Zweig/Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95565-214-2 (articles in German, English, French, Portuguese and Spanish).

- The Invisible Collection . Golden Luft Verlag, Mainz 2017, ISBN 978-3-9818555-1-7 .

- Joseph Fouche. Portrait of a political man. Anaconda Verlag, Cologne 2018, ISBN 978-3-7306-0669-8 .

correspondence

-

Letters, Four Volumes . edited by Knut Beck, Jeffrey B. Berlin et al., Verlag S. Fischer:

- Letters 1897–1914 , Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 978-3-10-097088-6 .

- Letters 1914–1919 , Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 978-3-10-097089-3 .

- Letters 1920–1931 , Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 978-3-10-097090-9 .

- Letters 1932–1942 , Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 978-3-10-097093-0 .

- Alfons Petzold - Stefan branch: correspondence . Introduction and commentary by David Turner, Peter Lang, New York 1998, ISBN 978-0-8204-3900-6 .

- letters to friends . edited by Richard Friedenthal , S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 978-3-10-097028-2 .

-

Correspondence with Friderike Zweig 1912–1942 , Scherz, Bern 1951.

- "If the clouds give way for a moment". Correspondence 1912–1942 (Stefan Zweig & Friderike Maria Zweig). edited by Jeffrey B. Berlin/Gert Kerschbaumer, S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 978-3-10-097096-1 .

- Correspondence with Hermann Bahr , Sigmund Freud , Rainer Maria Rilke and Arthur Schnitzler . edited by Jeffrey B. Berlin et al., S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 978-3-10-097081-7 .

- Correspondence with Romain Rolland 1910–1940 . 2 volumes, Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1987.

- Georges Duhamel -Stefan Zweig. correspondence . L'anthologie oubliée de Leipzig. edited by Claudine Delphis, University Press, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 978-3-934565-85-2 .

- Hermann Hesse and Stefan Zweig: Correspondence . edited by Volker Michels , Suhrkamp (BS 1407), Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 978-3-518-22407-6 .

- Maxim Gorki / Stefan Zweig: Correspondence . Documents. edited by Kurt Böttcher, Reclam (UB 456), Leipzig 1971.

- Rainer Maria Rilke and Stefan Zweig in letters and documents . edited by Donald A. Prater , Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 978-3-458-14290-4 .

- Richard Strauss -Stefan Zweig. correspondence . edited by Willi Schuh, S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1957.

- Stefan Zweig and Paul Zech . Letters 1910–1942 , Greifen, Rudolstadt 1984, ISBN 978-3-596-25911-3 .

- Stefan Zweig—Joseph Gregor. Correspondence 1921-1938. Edited by Kenneth Birkin, Univ. of Otago, Dunedin 1991, ISBN 0959765050 .

- The Correspondence of Stefan Zweig with Raoul Auernheimer and with Richard Beer-Hofmann . edited by Donald G. Daviau et al., Camden House, Columbia 1983, ISBN 0-938100-22-X .

- Perhaps we have two different languages... – On the correspondence between Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig. With 21 previously unpublished letters. edited by Matjaz Birk, Lit, Munster 1996, ISBN 978-3-8258-3182-0 .

- Any friendship with me is fatal. Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig. Correspondence 1927–1939 , eds. Madeleine Pietra and Rainer-Joachim Siegel. Wallstein-Verlag, Goettingen 2011. ISBN 978-3-8353-0842-8 . Publisher's page (with excerpt 20p.)

- Stefan and Lotte Zweig's South American Letters: New York, Argentina and Brazil 1940–42 . Eds. Darién J.Davis / Oliver Marshall. Continuum, London/New York 2010, ISBN 978-1-4411-0712-1 .

- Stefan and Lotte Zweig's South American Letters: New York, Argentina, and Brazil 1940–1942 . Eds. Darién J.Davis, Oliver Marshall. Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-95565-188-6 .

- I wish you missed me a little. Letters to Lotte Zweig 1934–1940 . Edited by Oliver Matuschek. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-596-95004-1 .

- Romain Rolland, Stefan Zweig: From world to world. Letters of a Friendship 1914–1918 . With an accompanying word by Peter Handke . Translated from the French by Eva and Gerhard Schewe and from the German by Christel Gersch. Aufbau Verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-8412-0816-3 .

- Hermann Bahr, Arthur Schnitzler: correspondence, records, documents 1891-1931. Eds. Kurt Ifkovits, Martin Anton Müller. Wallstein, Göttingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-8353-3228-7 ( publisher's presentation ) Several letters from Zweig to Hermann Bahr and Arthur Schnitzler and one from Schnitzler

- Letters on Judaism. Ed. Stefan Litt , Jüdischer Verlag im Suhrkamp-Verlag, Berlin 2020, ISBN 978-3-633-54306-9 ( publisher's presentation )

audio books

- Great moments of humanity read by Jürgen Hentsch , director: Petra Meyenburg , 551 min., 10 CDs, MDR 2008 / Argon Verlag 2008, ISBN 978-3-86610-571-3 .

- The world of yesterday. Memoirs of a European . Mono Verlag , Vienna 2013, Narrator: Peter Vilnai , ISBN 978-3-902727-17-6 .

- Casanova - Mesmer - Amerigo read by Dieter Mann , Wolfram Berger , Peter Matić , 9:20 h, MDR Figaro , 2013 / Der Audio Verlag 2015, ISBN 978-3-86231-633-5 .

- Joseph Fouché : Portrait of a Political Man Read by Hans Lietzau , Der Audio Verlag 2015, ISBN 978-3-86231-628-1 .

translation

- Émile Verhaeren : Rembrandt , Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1912 and 1923.

- Émile Verhaeren : Rubens , Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1913 and 1920.

- Luigi Pirandello : Fausto De Michele (ed.): Non si sa come Man does not know how Stefan Zweig traduce Luigi Pirandello. Bibliotheca Aretina, Arezzo 2012.

Among the translators with whom Zweig worked and were friends is the Frenchman Alzir Hella .

film adaptations

Since the 1920s, Zweig's literary work has also been filmed internationally. Some of his works, such as The Amok Runner , several times. Below is a selection:

- 1924: The House by the Sea

- 1928: Fear

- 1931: 24 hours from a woman's life

- 1933: Burning Mystery

- 1938: Marie Antoinett

- 1946: Impatience of the heart

- 1948: Letter from an unknown woman

- 1951: The Stolen Year (based on a novel fragment)

- 1954: Fear

- 1960: Chess novella

- 1968: 24 Hours of a Woman's Life

- 2013: A Promise (based on the bequest short story Journey into the Past)

- 2021: Chess novella

movies

- lost branch . is the first film adaptation that covers the last lifetime of Stefan and Lotte Zweig. Directed by Sylvio Back, Stefan Zweig: Rüdiger Vogler , Lotte Zweig: Ruth Rieser (Drama, 114 min., Brazil 2002) A Brazilian production, shot in English in Rio de Janeiro and Petrópolis. At the Brasilia Film Festival, Ruth Rieser received the "Candango" 2003 for her portrayal of Lotte Zweig, "best actress". The Candango is the most important film prize in the film country of Brazil.

-

The Grand Budapest Hotel . Feature Film, UK, Germany, USA, 2014, 100 min., Script: Wes Anderson and Hugo Guinness , Director: Wes Anderson.

The credits state that the film is partly inspired by Zweig's work. Anderson was inspired when he read the works Impatience of the Heart , The World of Yesterday and Twenty-Four Hours from the Life of a Woman by the author Stefan Zweig, who he had never known before.

- Stefan Zweig. A European of the world. (OT: Stefan Zweig, histoire d'un Européen. ) Documentary film, France, 2015, 51:30 min., written and directed by: François Busnel and Jean-Pierre Devillers, production: Rosebud Productions, arte France, first broadcast: January 6th 2016 at arte, synopsis of ARD , online video .

- In 2016, an Austrian-German-French co-production, directed by Maria Schrader , was released in cinemas under the title Before the Dawning Red , covering the last years of Zweig's life. Zweig is played by Josef Hader , Friderike Zweig by Barbara Sukowa , Lotte Zweig by Aenne Schwarz .

literature

- Stephen branch . In: Heinz Ludwig Arnold (ed.): Kindler's Literature Encyclopedia . 18 volumes, Metzler, Stuttgart/Weimar 2009, ISBN 978-3-476-04000-8 , Volume 17, pp. 826-828 [biogram, work article Angst und Sternstunden der Menschen von Gertraude Wilhelm, Der Amokjäger by Marta Abrahamson and Schachnovelle von Manfred Kluge].

- Hannah Arendt : St. Z. - Jews in the world of yesterday. In: Hannah Arendt: Six Essays. Schneider, Heidelberg 1948; again in: Hannah Arendt: The Hidden Tradition. Eight Essays. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1976.

- Hanns Arens (ed.): The great European Stefan branch. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1981, ISBN 3-596-25098-6 .

- Joachim Bruges (ed.): The book as an entrance to the world. For the opening of the Stefan-Zweig-Centre Salzburg, on November 28, 2008. Publication series of the Stefan Zweig Center Salzburg , Volume 1, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8260-3983-6 .

- Alfredo Bauer : Stefan Zweig in Argentina. In: intermediate world. Literature, Resistance, Exile. Theodor Kramer Society, Vol. 28, No. 3, October 2011, ISSN 1606-4321 , p. 52ff.

- Dominique Bona : Stefan Zweig l'ami blessé. Grasset, Paris 2010, ISBN 978-2-246-77251-4 .

- Susanne Buchinger: Stefan Zweig: Writer and literary agent. Relations with his German-language publishers 1901–1942 . Booksellers Association, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-7657-2132-8 . (Also: dissertation from the University of Mainz , 1995/96 udT: Susanne Buchinger: Stefan Zweig - writer, mediator and literary advisor ).

- Renate Chédin: The tragedy of existence. Stefan Zweig's "The World of Yesterday". Königshausen & Neumann, Wuerzburg 1996, ISBN 3-8260-1215-1 .

- Alberto Dines : Death in Paradise. The Tragedy of Stefan Zweig . Buchergilde Gutenberg, Frankfurt 2006, ISBN 3-7632-5697-0 .

- Alberto Dines, Israel Beloch, Kristina Michahelles: Stefan Zweig and his circle of friends: his last address book 1940–1942 . Translated from Brazilian Portuguese by Stephan Krier. 1st edition, Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-95565-134-3 .

- Andrea Drumbl : From the Desperate Leap into the Irrevocable . On the topic of suicide in texts by Stefan Zweig. Diploma thesis, Vienna 2006.

- Thomas Eicher (ed.): Stefan branch in current affairs of the 20th century . Athena, Oberhausen 2003, ISBN 3-89896-143-5 .

- Erich Fitzbauer (ed.): Stefan branch: Reflections of a creative personality . First special publication of the Stefan Zweig Society, Bergland, Vienna 1959.

- Walburga Freund-Spork: Explanations on Stefan Zweig, Schachnovelle . Bange, Hollfeld 2002, ISBN 3-8044-1736-1 .

- Mark H. Gelber : Stefan Zweig, Judaism and Zionism. Studien-Verlag, Innsbruck 2014, ISBN 978-3-7065-5303-2 .

- Thomas Haenel: A passionate psychologist. Stefan Zweig - life and work from the point of view of a psychiatrist. Droste, Düsseldorf 1995, ISBN 3-7700-1035-3 .

- Heinrich Eduard Jacob : From the Petropolis police files. On the 10th anniversary of Stefan Zweig's death. In: Die Neue Zeitung (The American newspaper in Germany) Frankfurt/Munich/Berlin, 23./24. February 1952.

- Gert Kerschbaumer : Stefan Zweig – The Flying Salzburger . Residence, Salzburg 2003, ISBN 3-7017-1336-7 .

- Sabine Kinder, Ellen Presser (ed.): "Time gives the pictures, I only speak the words." Stefan Zweig 1881-1942. For the exhibition of the Munich City Library on the Gasteig, 1993.

- Randolph J. Klawiter: Stefan Zweig. An International Bibliography. Ariadne Press, Riverside 1991.

- Heinz Lunzer, Gerhard Renner (eds.): Stefan branch 1881-1981. essays and documents. Circular, special number 2 (October 1981). Published by the documentation center for modern Austrian literature in cooperation with the Salzburg Literature Archive, Vienna 1981.

- Stephan Matthias, Oliver Matuschek: Stefan Zweig's Libraries . Publisher: Salzburg Literature Archive, research center of the University, State and City of Salzburg. Sandstein Verlag, Dresden 2018, ISBN 978-3-95498-446-6 .

- Oliver Matuschek: Three Lives. Stefan Zweig. A biography. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-10-048921-7 .

- Hartmut Müller: Stefan Zweig. With personal testimonials and photo documents . Rowohlt TB 413, Reinbek 1988, ISBN 3-499-50413-8 .

- Donald A. Prater : Stefan Zweig. The life of an impatient. A biography. Translated by Annelie Hohenemser. Hanser, Munich/Vienna 1981, ISBN 3-446-13362-3 .

- Donald A. Prater, Volker Michel (eds.): Stefan Zweig. Life and work in the picture. Insel, Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-458-32232-9 .

- George Prochnik : The Impossible Exile. Stefan Zweig at the end of the world. Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69756-2 .

- Ursula Prutsch, Klaus Zeyringer: The worlds of Paul Frischauer. A 'literary adventurer' in the historical context of Vienna – London – Rio – New York – Vienna. Böhlau, Vienna and others 1997, ISBN 3-205-98748-9 .

- Guo-Qiang Ren: At the end of disregard? Study on the Stefan Zweig reception in German literature after 1945. Shaker, Aachen 1996, ISBN 3-8265-1676-1 , (also: dissertation from the University of Giessen , 1995).

- Klemens Renoldner, Hildemar Holl, Peter Karlhuber (eds.): Stefan Zweig. For a Europe of the spirit. Exhibition catalogue, Salzburg 1992.

- Gabriella Rovagnati: "Detours on the way to myself". On the life and work of Stefan Zweig. Bouvier, Bonn 1998, ISBN 3-416-02780-9 .

- Marek Scherlag: Stefan Zweig. In: intermediate world. Literature, Resistance, Exile. Theodor Kramer Society , vol. 24, no. 1/2; October 2007, ISSN 1606-4321 , pp. 25–28.

- Sigrid Schmid-Bortenschlager, Werner Riemer (ed.): Stefan branch is alive! Files of the 2nd International Stefan Zweig Congress in Salzburg 1998. Hans-Dieter Heinz, Stuttgart 1999.

- Ingrid Schwamborn (ed.): The last game. Stefan Zweig's life and work in Brazil 1932–1942. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 1999, ISBN 3-89528-211-1 .

- Giorgia Sogos: A European in Brazil between past and future: utopian projections of the exile Stefan Zweig , In: Lydia Schmuck, Marina Corrêa (ed.): Europe in the mirror of migration and exile / Europa no contexto de migração e exílio . Projections – Imaginations – Hybrid Identities/Projecções – Imaginações – Identidades híbridas. Frank & Timme Verlag for scientific literature, Berlin 2015, pp. 115-134, ISBN 978-3-7329-0082-4 .

- Giorgia Sogos: Stefan Zweig, the cosmopolitan. Study collection on his works and other contributions. A critical analysis. Free Pen Verlag, Bonn 2017, ISBN 978-3-945177-43-3 .

- Bastian Spangenberg: 'Citizen of the World' as a refugee. Stefan Zweig and the loss of the “spiritual homeland” . Master's thesis, University of Vienna 2016.

- David Turner, Moral Values and the Human Zoo. The "novellen" of Stefan Zweig. Hull UP, Hull 1988, ISBN 0-85958-494-1 .

- Wolfgang Treitler: Between Job and Jeremiah. Stefan Zweig and Joseph Roth at the end of the world. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2006, ISBN 978-3-631-55391-6 .

- Jörg Ulrich : ZWEIG, Stefan. In: Biographical-Bibliographical Church Lexicon (BBKL). Volume 18, Bautz, Herzberg 2001, ISBN 3-88309-086-7 , col. 1576-1600.

- Volker Weidermann : "Hell reigns!" Stefan Zweig and Joseph Roth - a friendship in letters. In: The Same: The Book of Burnt Books . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-462-03962-7 , pp. 232-240.

- Ulrich Weinzierl (ed.): Stefan branch, triumph and tragedy. Essays, diary notes, letters. Fischer paperback publishing house, Frankfurt 1992, ISBN 3-596-10961-2 .

- Ulrich Weinzierl: Stefan Zweig's burning secret. Paul Zsolnay, Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-552-05742-5 .

- Friderike branch: Stefan branch. How I experienced him. Herbig, Berlin 1948.

web links

- Works by and about Stefan Zweig in the German Digital Library

- Works by Stefan Zweig in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Stefan Zweig Bibliography

- Original sounds from and archive recordings about Stefan Zweig in the online archive of the Austrian media library

- Stefan Zweig: Great moments of humanity Audio of a reading in 15 episodes with Jürgen Hentsch

About Stefan Zweig

- Stefan Zweig in the Vienna History Wiki of the City of Vienna

- Short biography and reviews of Stefan Zweig's works at PERLENTUBE.DE

- Stefan Zweig Center Salzburg

- Entry about Stefan Zweig in the Austria-Forum

- stefanzweig.de

- International Stefan Zweig Society (ISZG)

- Stefan Zweig digital - digital estate reconstruction

- Stefan Zweig House , Petrópolis, Brazil

- Christiane Kopka: November 28, 1881 - The writer Stefan Zweig is born WDR Zeitzeichen from November 28, 2021; with Michael Scheffel . (podcast)

itemizations

- ↑ Death certificate (óbito) : falecido aos 23 de fevereiro del 1942 às 12 horas e 30' = deceased on February 23, 1942, 12:30 p.m.

- ↑ Eva Plank: The secret of Stefan Zweig's Jewish first name , in: Stefan Zweig Center Salzburg (ed.): Zweigheft 15 , Salzburg 2016, pp. 21-28.

- ↑ Entry "Zweig, Stefan". In: Munzinger Online/Persons - International Biographical Archive. Retrieved August 9, 2017 .

- ↑ The World of Yesterday

- ↑ Addresses according to Adolph Lehmann's address book, edition 1894; both factory addresses no longer exist after the Second World War.

- ↑ Donald A. Prater: Stefan Zweig. The life of an impatient. Munich/Vienna 1981.

- ↑ Oliver Matuschek: Stefan Zweig. three lives. A biography. Frankfurt am Main 2006.

- ↑ Benno Geiger: Memorie di un Veneziano. Florence 1958; Treviso 2009.

- ↑ Klemens Dieckhöfer: Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) and the importance of the bionegative in his life. A contribution to the question of his exhibitionism and as a comment from a psychiatric point of view. In: Medical-Historical Communications. Journal for the history of science and specialist prose research. Volume 34, 2015, pp. 129–135, here: p. 129.

-

↑ Ulrich Weinzierl : Stefan Zweig's burning secret. Zsolnay, Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-552-05742-5 , ( limited preview at Google Books ).

Stefan Gmünder: Stefan branch: A writer in the pillory . In: Der Standard , September 28, 2015.

Jan Küveler: Stefan Zweig was an exhibitionist . In: Die Welt , September 18, 2015. - ↑ Stefan Zweig's burning secret. In: orf.at , September 19, 2015.

- ↑ Klemens Dieckhöfer: Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) and the importance of the bionegative in his life. A contribution to the question of his exhibitionism and as a comment from a psychiatric point of view. In: Medical-Historical Communications. Journal for the history of science and specialist prose research. Volume 34, 2015, pp. 129–135, here: p. 134.

- ↑ Stefan Zweig: Collected works in individual volumes. The world of yesterday, memories of a European. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-10-097047-0 , p. 290.

- ↑ Erwin Rieger: Stefan Zweig. Berlin 1928.

- ↑ The World of Yesterday. p. 326 f.

- ↑ Susanne Buchinger: Stefan Zweig - writer and literary agent. Relations with his German-language publishers (1901–1942) . Association of Booksellers, Frankfurt am Main 1998, p. 152.

- ↑ The World of Yesterday. p. 445.

- ↑ The World of Yesterday. p. 444.

- ↑ Susanne Buchinger: Stefan Zweig - Writer and Literary Agent , Frankfurt am Main 1998, page 235 ff.

- ↑ The World of Yesterday. p. 334 (Chapter Incipit Hitler ).

- ↑ The World of Yesterday. p. 428 ff.

- ↑ Arnold Bauer: Stefan Zweig . Colloquium Verlag, Berlin, 1985, ISBN 3-7678-0659-2 .

- ↑ - An unequal relationship. Retrieved May 29, 2020 .

- ↑ Frederike M. Zweig: Stefan Zweig. How I experienced him. Neuer NV Verlag, Stockholm 1947, chap. The house breaks down .

- ↑ The World of Yesterday. p. 497.

- ↑ Klaus Hart: Bad people. Antisemitism in South America - widespread and little researched. In: New Zurich newspaper . 11 November 2008, retrieved 15 July 2013 .

- ↑ Kai Nonnenmacher: Before dawn: Stefan Zweig in Brazil . 6 June 2016 ( academia.edu ).

- ↑ Senate decision of the University of Vienna of April 10, 2003. ( Memento of November 19, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 126 kB), retrieved on April 3, 2013.

- ↑ Matthias Rüb: The phantasm of Brazil. The writer Stefan Zweig is said to have spent the last months of his life in Petrópolis happily. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of February 23, 2017, p. 9.

- ↑ According to the death certificate : ingestão de substantia toxica – suicidio

- ↑ Thomas Milz: Brazil: Lost in Paradise. Stefan Zweig in Petropolis . ( Memento from January 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: caiman.de , 2008, No. 4.

- ^ Stefan Zweig's farewell letter . ( Wikisource )

- ↑ Ulrike Wiebrecht: No future in miniature Ischl . In: taz , February 25, 2009. - Marlen Eckl: A tiny bungalow in a beautiful landscape. ( Memento of January 31, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) In: tópicos , 2006, No. 2, (PDF; 137 kB), cf. casastefanzweig.org

- ↑ orf.at: Brazil honors branch posthumously with the highest distinction . Article of December 18, 2017, accessed December 19, 2017.

- ↑ Salzburg University of Education: PH Salzburg: branch office. Retrieved 16 May 2021 .

- ↑ See Jacques Le Rider: The Dream of a United Europe , in: Der Standard , 18 February 2017, p. 41.

- ↑ Cf. Klemens Renoldner: A voice that has retained its topicality , in: Der Standard , February 18, 2017, p. 40.

- ↑ Cf. et al. William M. Johnston: On the cultural history of Austria and Hungary 1890-1938. Böhlau, Cologne/Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-205-79378-6 , p. 49.

- ↑ Catalog sheet University Library Vienna

- ↑ Full text of an English translation. (German History in Documents and Images.) Also appeared in Anton Kaes, Martin Jay, and Edward Dimendberg: Regents of the University of California , University of California Press, pp. 397–400. (1994)

- ↑ Stefan Zweig, Wes Anderson, Anthea Bell: The society of the crossed keys. Selections from the writings of Stefan Zweig, Inspirations for the Grand Budapest Hotel. Pushkin Press, London 2014, ISBN 978-1-78227-107-9 .

- ↑ George Prochnik: 'I stole from Stefan Zweig'. Wes Anderson on the author who inspired his latest movie . In: The Telegraph , 8 March 2014, accessed 21 March 2014, Interview with Anderson.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | branch, Stefan |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British-Austrian writer |

| BIRTH DATE | Nov. 28, 1881 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 23, 1942 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Petropolis near Rio de Janeiro |