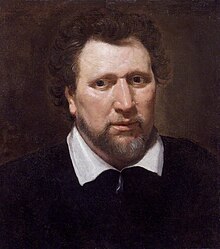

Ben Jonson

Ben Jonson , actually Benjamin Jonson (born June 11 (uncertain) 1572 in London , † August 6, 1637 ibid), was an English playwright and poet. Along with William Shakespeare , Ben Jonson is considered to be the most important English playwright of the Renaissance .

life and work

Jonson was born in Westminster . His father, a Protestant clergyman, had died shortly before Jonson was born. Jonson learned his stepfather's trade, a bricklayer. Later he was a soldier and then apparently a driving actor. During this time he wrote his first pieces. From 1597 Jonson was an actor and playwright in the service of Philip Henslowe . Presumably he completed the lost satirical play The Isle of Dogs , begun by Thomas Nashe , which led to a scandal with a temporary closure of the theaters and earned Jonson his first prison sentence. He had his breakthrough as an author in 1598 with Every Man in his Humor , which was successfully performed as an actor by the Lord Chamberlain's Men with the participation of Shakespeare.

Shortly thereafter, Ben Jonson killed the actor Gabriel Spencer in a duel and ended up in prison for a short time, but escaped the death penalty because he could invoke the so-called benefit of the clergy , i.e. his ability to read Latin Bible texts recite. However, this did not prevent his branding. During his brief imprisonment, Jonson converted to the Roman Catholic faith.

His writing career peaked between 1605 and 1614; his most important pieces were created during this period. The general recognition and appreciation of Jonson at the time was reflected in the publication of the meticulously edited folio edition of his works, which was the first of its kind to appear in 1616 even before the posthumous folio edition of Shakespeare's works during his lifetime . After Jonson's death, a second expanded folio edition of his works was published in 1640. In particular, his four comedies Volpone , The Alchemist , Bartholomew Fair and The Silent Woman were highly praised and were regularly part of the repertoire of English theaters.

In the first three decades of the 17th century, Jonson played an essential role in the theater and literary life of London. During the reigns of James I and Charles I , from 1605 to 1634 he regularly wrote courtly masquerades in collaboration with Inigo Jones . This soon won him the favor of the king; so he was under the patronage of James I, who gave him a salary and thus a de facto position as court poet. Jones was later honored as a Poet Laureate and thus officially named court poet.

Jonson spent the last years of his life paralyzed after a stroke . He died on August 6, 1637 and was buried in Westminster Abbey . Jonson was married; his children died young.

Artistic creation

Although Jonson undoubtedly wrote works of high standing (e.g. the comedies Volpone and The Alchemist ), it was more his artistic antagonism to his contemporary William Shakespeare that has always preoccupied literary studies. The verdict small Latin and less Greek (“little knowledge of Latin and even less of Greek”) from his necrology on Shakespeare is famous .

Jonson saw himself as a learned poet and, in the continuation of the Renaissance, was an ardent admirer of ancient , especially Roman, literature, without, however, in any way associating it with a cosmopolitanism or forgoing the development of his own literary profile. Based on the Roman comedy, he mainly founded a new form of satirical moral comedy, which lasted into the 18th century.

Jonson saw himself not only as a dramatist, but also always as a lyric poet who designed his poetry on the basis of ancient genres such as epigram , epitaph , epistle or ode . He rejected the style of metaphysical poets with often sought-after or excessive metaphors ( conceits ) and placed great emphasis on clarity of form and simplicity of expression. As a result, he contributed significantly to the development of the ideal of a plain style .

Jonson's early creative phase as a playwright was shaped by his invention of the comedy of humor as a special variety of the comedy of manners . He took up the theory of the different bodily fluids and four temperaments of the choleric , sanguine , melancholic and phlegmatic , which is based on ancient and medieval humoral pathology . It was his particular achievement to use this teaching metaphorically to illustrate the eccentricities and affectations of people in social life. The individual episodes of this variant of the comedy serve primarily to reveal the individual humours ; the aim of the entire event is primarily aimed at healing the humours , which essentially only embody exaggerations of fundamentally desirable properties.

In Every Man in His Humor , the humoral-psychological moment occurs initially only in two characters who cultivate melancholy as a fashion disease. The original version of this comedy takes place in Italy; in a later revised version, Jonson moved the scene to England and converted the comedy form from the model of the Roman comedy poet Plautus to the city comedy typical of him . The central issue is the generation conflict , illustrated using the example of the father Knowell , who spied on his son because he was concerned about his morale. A central role as a schemer and change artist also plays the servant Brainworm , which the Roman comedy as well as the vice figure (as a figure both in the tradition of slaves figures Vice ) of the medieval morality plays is. All main characters are determined by a fixed idea, which is usually already expressed in their speaking names . Also spectacular is the figure of Bobadill , a coward and braggart, who flaunts his alleged expertise as a soldier with bombastic gestures and rhetoric and thus succeeds the ancient Miles Gloriosus in Jonson's work .

In Every Man out of His Humor the character-related drama is further expanded and perfected; On the basis of Jonson's poetological view that man defines himself primarily through his language, the characterization in the figure drawing is reinforced by the respective language use. The plot is more episodic and is subordinated to the representation of the eccentricities. An essential dramaturgical innovation of Jonson lies in the introduction of commentary figures, which are introduced in the induction and remain present outside the action throughout the course of the play. Internally, they cover the humor figures with reproach and ridicule. The comment characters that appear in the framework of the plot include fictional viewers and critics who not only discuss the function of individual scenes, but also use the play to thematize the meaning and essence of the comedy itself. Through this epic alienation and the breaking of illusions in the framework game, the immediate drama is restricted and the spectator is shown the illusion of the theatrical mimesis in the comedy of humours . The satirical moment is also pronounced in this piece. Criticism of court life is realized through characters who, as city or country dwellers, mimick courtly behavior and who want to rise in society by acquiring attributes of the courtier status such as clothing or coats of arms.

One of Jonson's most cheerful works is Epicoene or The Silent Woman ; In an extremely comical way, the contrast between the sexes is abolished here on all levels of action, characterization and language. The initially apparently silent and patient title character of the Epicoene turns into a loud, domineering quarrel after their marriage and ultimately turns out to be a man in women's clothes. It is brought to the old Morose and contrasted, whose rejection of life is expressed in a completely excessive sensitivity to noise and an almost unnatural need for rest. From this starting point, a fundamental situational comedy results in the main plot, which is varied again and again in staggered form. At the same time, the deconstruction and reversal of gender roles is further developed thematically through artfully integrated subplots.

Jonson's masterpieces are primarily the two rogue comedies Volpone and The Alchemist , which are characterized by great virtuosity in the art of characterization, dialogue design and plot management. Volpone plays in Venice, traditionally a place of vice and debauchery for Jonson's contemporaries. With the naming of the main characters, Jonson evokes the fable tradition and transposes the events to the level of the animal fable without, however, turning the characters into mere allegorical personifications. The title character Volpone (fox) pretends to be terminally ill in order to dupe various inheritance sneaks, a merchant, a lawyer and an old curmudgeon, and to enrich himself in them. Volpone is supported in his deception maneuvers by his shrewd servant Mosca (fly).

While the legacy sneakers and deceived fraudsters Voltore (vulture), Corbaccio (raven) and Corvino (crow) have given up all moral principles out of pure greed, Volpone and his servant Mosca are concerned with the intellectual enjoyment and enjoyment of skillful money-making about the power that gold gives. As a symbol of power, gold has metaphysical qualities for Volpone, as he already expresses in the first scene in his blasphemous liturgy. Volpone's lust for power is also expressed in his glowing sensuality; the wealth is also made subservient to fulfill his desire for Celia (in the German translation Colomba) and to win her over. In contrast to the other fraudsters, whose human meanness is depicted much more blatantly, the central pair of crooks knows how to master even the most precarious situations with flying colors and to skillfully stage their strategies of deception. Volpone shows himself to be a master at simulating diseases; Mosca skillfully manipulates language as a means of deceit and hypocrisy. The technical brilliance of the cheating couple mostly causes the viewer to postpone ethical evaluations; the artistically designed course of action with well-dosed increases, increasing complications and a breathtaking abundance of surprising twists allows the viewer to follow the dramatic events with pleasure or pleasure.

Ultimately, however, Volpone and Mosca overdone themselves in their initially successful deception; their complicity breaks and both face severe punishment in the end. In the end, this will restore the moral or legal order; however, there are no positive opposing forces that are otherwise characteristic of comedy that could triumph in the end.

Jonson's second crook comedy The Alchemist shows an even greater intellectual variety and perfection in the plot construction, which cleverly links several parallel plots with the main plot. Numerous other topics flow into the satire on quackery , charlatanry and greed. The action takes place in London, where the deceitful butler Jeremy alias Face, in the absence of his master, together with the alchemist Subtle and the prostitute Doll Common, develop a wide-ranging network of fraudulent actions to sell illusions to a number of clients. The theme of greed for gold that connects The Alchemist with Volpone is reduced to a smaller level, but varied in a more diverse way in order to emphasize the specific needs of the customers who visit the alchemist's workshop. The complexity of the characters and their motifs also increases, from the naive scribe Dapper, who only wants to win the lottery, to the dazzling figure of Sir Epicure Mammon, who wants to realize his visions and fantasies of wealth and lust with the help of the philosopher's stone . In The Alchemist , Jonson also combines his satirical criticism of the contemporary fascination with astrology, alchemy and quackery with a satire on the hypocrisy and fanaticism as well as the opportunism of the Puritans in the form of the twin figures Ananias and Tribulation.

Jonson presented another innovation in 1614 in his next, more important work, Bartholomew Fair , which in a dense series of episodes presents a broad panorama of London life and a kaleidoscope of human inadequacies, as it were in a revue piece. This colorful picture sheet shows in rapidly changing scenes the fates of 30 visitors to the fair that was held on August 24th in Smithfield. Although there are scams here too, Bartholomew Fair is not a rogue comedy in the strict sense of the word. Although various grievances are presented, from fraudulent pouring to prostitution, the focus is on the different people with their respective illusions and obsessions. The satirical form of representation characteristic of Jonson can also be found here, for example in the figure of the Zeal-of-the-Land-Busy; overall, however, the comedy and a cheerful tone predominate. More than in earlier plays, Bartholomew Fair is also characterized by a tendency towards realism. At the end, the stage company gathers to perform a puppet show. The Puritan Zeal, like the Puritans in real life an enemy of the theater, succumbs in the debate with a puppet character about the value and morals of acting. The play ends with an invitation from the judge Adam Overdo, who was looking for monstrosities ( enormities ) at the fair , to a joint dinner for everyone.

In addition to his comedies, Jonson also wrote two tragedies, Sejanus His Fall and Catiline His Conspiracy . Sejanus is a gloomy work that is shaped by Machiavellianism and presents political life as a power struggle determined by general unscrupulousness and exaggerated ambition. The winners turn out to be those who are more subtle in deceiving and who are better at disguising themselves. Those who are not capable of doing this become victims who are left with helpless commentary on what has happened.

With his numerous mask games from 1605 Jonson also gave the Jacobean mask its characteristic shape and shape with a variety of new motifs. As a novelty, he introduced the so-called anti-masque , which was supposed to serve as a comical-grotesque prelude to emphasize the politically affirmative character of the actual courtly masquerade aimed at harmony all the more clearly. Until their separation in the dispute in 1631, Jonson mostly worked with Inigo Jones as a set designer in the design of his mask games, which were regularly performed with great success at court . Despite his high reputation at the court as an author, he was sentenced to prison again in 1605 for having ridiculed the Scottish nobility in Eastward Hoe , which he had written with George Chapman and John Marston .

In Shakespeare research, the influence of Jonson's satirical comedies on individual works such as Twelfth Night or All's Well That Ends Well is considered proven by many scholars .

The striving for classical strictness of form, which is characteristic of Jonson's dramas, also shaped his lyrical works, in which he primarily used the ancient forms of the epigram, the epigraph, the ode and the verse epistle. Against the prevailing language boom, which Jonson blamed in particular on the influence of Edmund Spenser , he enforced the "plain style" . With the publication of the dramatic and lyrical works he had completed by then in the first folio edition of 1616, Jonson also tried to make visible the literary significance that he saw in his work. In his later work he was no longer able to build on the successes of his earlier master comedies. His old age was not only overshadowed by illness, but also by the loss of his beloved library, which was destroyed by a fire.

Regardless of this, Jonson gathered a large circle of friends and students who, as tribe of Ben or sons of Ben, saw in him their literary role model or their teacher. In Timber , a collection of critical notes, Jonson put down his poetic theory. A number of his more significant critical comments are also preserved in the notes of the Scottish poet William Drummond of Hawthornden , whom Jonson visited on a trip to Scotland.

Along with Shakespeare and Marlowe , Jonson was one of the most important playwrights of the time. He saw himself in particular as a reformer of literature and society. In contrast to Shakespeare, he was a classicist and endeavored to give the drama of his time, which at the time was not regarded as serious literature, literary validity and recognition through strict design in the sense of Aristotelian poetics . By the human image of a Christian humanism influenced he criticized as a staunch supporter of the absolutist monarchy and the hierarchical caste system that in Puritan expanding middle class economic and social behaviors.

With his advocacy of simplicity, clarity and accuracy in the use of poetic language and his turn to Aristotelian poetics, he made a significant contribution to strengthening the tendency towards purity of the genre and strictness of form as well as the imitation of ancient forms during the restoration period . Due to his influence on his contemporaries, his extensive reading, his keen judgment and his language skills, he was also considered one of the pioneers of English classicism during the Restoration .

It was only with the emergence of the Shakespeare cult of the 18th century that he was devalued for a long time as the epitome of a pedantically correct playwright in contrast to the “natural genius” Shakespeare. On the other hand, in the literary criticism of the 20th century, efforts are again made towards an unbiased assessment and assessment of Jonson's artistic standing. In recent literary studies and criticism, he was partially rediscovered as “one of the greatest satirical comedy poets in world literature”.

Works

- Every Man in his Humor (1598)

- Every Man out of his Humor (1599)

- Cynthia's Revels (1600)

- The Poetaster (1601)

- Sejanus His Fall (1603) (German translation 1912 by Margarete Mauthner Der Sturz des Sejanus )

- Volpone (1606?) ( Volpone (Stefan Zweig) free adaptation by Stefan Zweig , 1926, German translation 1912 by Margarete Mauthner and 1972 by Uwe Friesel )

- Epicoene or The Silent Woman , Komödie (1609) (German translation by Ludwig Tieck , 1800, set to music by Antonio Salieri as Angiolina (1800) and Richard Strauss as Die Schweigsame Frau , text book by Stefan Zweig, 1935)

- The Alchemist (1610) (incidental music The Alchemist by Georg Friedrich Händel )

- Catiline His Conspiracy (1611)

- Bartholomew Fair (1614) (German translation 1912 by Margarete Mauthner Bartholomäusmarkt )

- The Devil is an Ass (1616)

- The Staple of News (1625)

- The New Inn (1629)

- The Magnetic Lady (1632)

- The Tale of a Tub (1633)

- The Sad Shepherd (unfinished)

- Timber: or Discoveries made upon Men and Matter (prose; published 1640)

literature

- Christiane Damlos-Kinzel: From Economics to Political Economy. Economic Discourse and Dramatic Practice in England from the 16th to the 18th Century. Würzburg: Königshausen u. Neumann 2003. ISBN 3-8260-2277-7 .

- Ian Donaldson: Ben Jonson: a life , Oxford [u. a.]: Oxford Univ. Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-812976-9 .

- W. Franke: Generic constants of the English verse epitaph from Ben Johnson to Alexander Pope. Philosophical dissertation, Erlangen 1864.

- Tom Lockwood: Ben Jonson in the Romantic Age. Oxford et al. a .: Oxford Univ. Press 2005. ISBN 0-19-928078-9 .

- James Loxley: The complete critical guide to Ben Jonson. London u. a .: Routledge 2002. ISBN 0-415-22227-3 .

- Norbert H. Platz: Ethics and Rhetoric in Ben Jonson's Dramas. Winter Verlag, Heidelberg 1976, ISBN 3-533-02464-4 .

- Elke Platz-Waury: Jonson's comical characters. Investigations into the relationship between poetry theory and stage practice. Nuremberg: Verlag Hans Carl 1976. ISBN 3-418-00056-8 .

- Karl Adalbert Preuschen: Ben Jonson as a humanistic dramatist. Studies on the stage works of the folio from 1616. Frankfurt am Main a. a .: Lang 1987. (= European university publications; series 14; Anglo-Saxon language and literature; 175) ISBN 3-8204-1094-5 .

- Hanna Scolnicov: Experiments in stage satire. An analysis of Ben Jonson's Every man out of his humor, Cynthia's revels and Poetaster. Frankfurt am Main u. a .: Lang 1987. (= European university studies; Ser. 14, Anglo-Saxon language and literature; 131) ISBN 3-8204-8149-4 .

- Peter Zehfuß: Fraud and self-deception. Ben Jonson's comedies "Volpone" and "The alchemist" against the backdrop of Elizabethan-Jacobean society and their significance for the present. Regensburg: Roderer 2001. (= theory and research; 698; literary studies; 30) ISBN 3-89783-217-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Ben Jonson in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Ben Jonson in the German Digital Library

- Ben Jonson . Works by Ben Jonson on Project Gutenberg (English)

- Works by Ben Jonson in the Gutenberg-DE project

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 305.

- ↑ See Bernhard Fabian (Ed.): The English literature. Volume 2: Authors . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 3rd edition, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-04495-0 , p. 229.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 306. See also Ben Jonson - English writer . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ See Ben Jonson - English writer . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ Cf. Walter Kluge: The Drama of the Restoration Time. In: Josefa Nünning (Ed.): The English Drama. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1973, without ISBN, pp. 274–316, here p. 297.

- ↑ See Ben Jonson - English writer . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved July 14, 2015. See also Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 306.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 305. See also Ben Jonson - English writer . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , pp. 305f. See also Ben Jonson - English writer . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ See Dietrich Rolle : The drama in the time of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts. In: Josefa Nünning (Ed.): The English Drama . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1973, without ISBN, pp. 203–273, here p. 244.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 306. See also Dietrich Rolle: The drama at the time of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts. In: Josefa Nünning (Ed.): The English Drama. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1973, without ISBN, pp. 203–273, here p. 242ff.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 306.

- ↑ See Dietrich Rolle: The drama in the time of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts. In: Josefa Nünning (Ed.): The English Drama. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1973, without ISBN, pp. 203–273, here p. 244.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 306. See also Manfred Pfister : Staged Reality: World stage and stage worlds. In: Hans Ulrich Seeber (Ed.): English literary history . 4th ext. Ed. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-476-02035-5 , pp. 129–135, here p. 132.

- ↑ See Dietrich Rolle: The drama in the time of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts. In: Josefa Nünning (Ed.): The English Drama. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1973, without ISBN, pp. 203-273, here pp. 255f. See also Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 306f.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 307. See also Dietrich Rolle: The drama at the time of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts. In: Josefa Nünning (Ed.): The English Drama. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1973, without ISBN, pp. 203-273, here pp. 252f. Likewise in more detail Jonas A. Barish: The double plot in Ben Jonson's> Volpone <. In: Willi Erzgräber (Hrsg.): English literature from More to Stars. Interpretations Volume 7. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. and Hamburg 1970, pp. 96-111.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 307. See also Dietrich Rolle: The drama at the time of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts. In: Josefa Nünning (Ed.): The English Drama. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1973, without ISBN, pp. 203-273, here pp. 253f.

- ↑ See Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 307. See also Dietrich Rolle: The drama at the time of Elizabeth and the early Stuarts. In: Josefa Nünning (Ed.): The English Drama. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1973, without ISBN, pp. 203–273, here p. 254.

- ↑ See Ben Jonson - English writer . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved July 14, 2015. See also Wolfgang G. Müller: Jonson Ben. In: Metzler Lexicon of English-Speaking Authors . 631 portraits - from the beginning to the present. Edited by Eberhard Kreutzer and Ansgar Nünning , Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-476-01746-X , p. 306.

- ↑ See Bernhard Fabian (Ed.): The English literature. Volume 2: Authors . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 3rd edition, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-04495-0 , p. 230.

- ^ Ina Schabert (Ed.): Shakespeare-Handbuch. Time, man, work, posterity. 2nd Edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-520-38602-X , p. 61f. (5th rev. New edition Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-520-38605-2 ).

- ↑ From this circle of Jonson's admirers, numerous of the subsequent cavalier poets (" cavalier poets ") emerged. See Bernhard Fabian , Willi Erzgräber , Kurt Tetzeli von Rosador and Wolfgang Weiß: The English literature. , Volume 2: Authors . dtv, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-4230-4495-0 , p. 75 (full text also available as a scan on [1] ).

- ↑ See Bernhard Fabian (Ed.): The English literature. Volume 2: Authors . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 3rd edition, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-04495-0 , p. 230 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Jonson, Ben |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jonson, Benjamin |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English playwright and poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | uncertain: June 11, 1572 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Westminster |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 6, 1637 |

| Place of death | London |