Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (born June 11, 1864 in Munich , † September 8, 1949 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen ) was a German composer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who was primarily known for his orchestral program music ( tone poems ), his songwriting and his operas became known. He is therefore counted among the composers of the late Romantic period . Strauss was also an important conductor and theater director and a campaigner for copyright reform.

Life

The beginnings (1864–1886)

Richard Strauss was born in Munich on June 11, 1864. His father Franz Strauss (1822-1905) was the first horn player at the Court Orchestra in Munich and since 1871 Academy professor, his mother Josephine Strauss (1838-1910) came from the brewer dynasty Pschorr , one of the richest families in Munich. Inspired by his parents' house, which was filled with music, primarily his father, Richard began to compose himself at the age of six. He later received composition lessons from the Munich conductor Friedrich Wilhelm Meyer. Under his guidance, after early pieces for piano and voice, the first larger forms emerged: concerts or concert pieces, a great sonata , a string quartet , two symphonies and a wind serenade . His official Opus 1 is a festival march for large orchestra , which he composed at the age of twelve.

In 1882 Strauss began studying philosophy , art history at the University of Munich , but soon broke it off again to devote himself entirely to a career as a musician. As early as 1883, the young composer's first works were performed in Munich, among others by Hofkapellmeister Hermann Levi . In 1883 Strauss went on an artist journey that took him to Dresden and Berlin for several months . During this trip he made important contacts, especially with the conductor and director of the court orchestra in Meiningen , Hans von Bülow . In 1885, he brought the young Strauss to the Meininger Hof as Kapellmeister. When Bülow resigned soon afterwards, Strauss was his successor for a short time.

In Meiningen, Strauss met Johannes Brahms , among others , and made friends with Alexander Ritter , the first violinist in Meiningen, son of the Wagner sponsor Julie Ritter and husband of Richard Wagner's niece (Franziska). Up until then Strauss had composed in the style of the classics as well as by composers such as Schumann or Brahms, but under the influence of the Wagnerian Ritter, his musical orientation changed. He turned to the music and the artistic ideals of Wagner , and with symphonic program music based on the symphonic poems by Franz Liszt , he practiced Wagner's orchestral style at Ritter's instigation in order to succeed his successor as a composer of musical dramas.

Conductor in Munich and Weimar (1886–1898)

On April 16, 1886, he signed a contract as the third conductor at the court opera in his hometown of Munich. The next day he left for Italy for five weeks. Immediately after returning to Munich, he began to compose the four-movement orchestral fantasy From Italy , which was premiered a year later in Munich under his own direction. On October 1, 1886, he stood for the first time at the podium of the Munich Court and National Theater and stayed there until July 31, 1887.

During this time he composed his first one-movement programmatic orchestral works, which he himself called tone poems . After initial difficulties ( there are no fewer than three versions of the first tone poem, Macbeth ), Strauss found his own unmistakable style in the tone poems Don Juan (1888/89) and above all Death and Transfiguration (1888–1890) made known. In addition, he began - also following his example Wagner - with the poetry of the libretto for his first opera Guntram , a medieval knight tale with echoes of the ideas of Richard Wagner and Arthur Schopenhauer .

In 1887 he met not only Gustav Mahler , but also the young soprano Pauline de Ahna , who became his student and later his wife and for whom he composed many songs. In Munich the young Kapellmeister was given the task of premiering Die Feen , a youth opera by Richard Wagner. When he was removed from the line before the dress rehearsal, he resigned and accepted an offer from Weimar . Before that, he accepted an invitation to Bayreuth , where he made himself useful as a musical assistant at the 1889 Festival and won the esteem of Cosima Wagner , who even wanted to marry him off to her daughter Eva. When he took up his position as second Kapellmeister (behind the Dane Eduard Lassen ) at the Weimar Court Theater on September 9, 1889 , he mainly campaigned for the performance of Wagner's works and performed Tannhäuser , Lohengrin as well as Tristan und Isolde and conducted the world premiere von Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel (December 23, 1893) and the world premieres of his tone poems Don Juan and Death and Transfiguration .

In May 1891, Strauss suffered severe pneumonia. During his convalescence in Feldafing , he wrote to his friend and critic Arthur Seidl : "To die would actually not be that bad, but I would like to conduct Tristan again."

On November 4, 1892, he traveled to Greece and on to Egypt for health reasons to cure a lung disease. He did not return until June 25, 1893. He completed most of his opera Guntram on this trip, although the revision of the third act led to a heated argument with Ritter, who criticized Strauss' decision to let Guntram determine his own life as a mistake. On May 10, 1894 Strauss conducted the premiere in Weimar, his future wife Pauline, to whom he had become engaged that morning, sang the part of Freihild, his pupil Heinrich Zeller took on the strenuous title role. At the Bayreuth Festival in 1894 he directed five Tannhauser performances for the first time , in which Pauline sang Elisabeth. The two married on September 10, 1894. Strauss subsequently accepted another position as court conductor in Munich. In parallel to his duties in Munich, he also led the Berlin Philharmonic for one concert season in place of his mentor Hans von Bülow, who died in February 1894 .

When Guntram , who only had a few performances in Weimar, also failed in Munich, Strauss turned again to symphonic poetry, but at the same time relentlessly looked for new stage material. At first he planned an opera Till Eulenspiegel with the Schildbürgern , but a new tone poem developed from it, Till Eulenspiegel's funny pranks , which was premiered in Cologne in 1895 by Franz Wüllner and had great success. The tone poems Also sprach Zarathustra (1896) and Don Quixote were created in quick succession, premiered in Frankfurt am Main and again in Cologne, and cemented Strauss' fame as a leading avant-garde artist. Soon he was also in demand as a conductor all over Europe. When he was denied the successor to Hermann Levi in Munich , he accepted a call to Berlin as the first royal Prussian court conductor to Berlin.

Opera composer and Berlin years (1898-1918)

Strauss made his Berlin debut on November 5, 1898 at the Hofoper Unter den Linden with Tristan and Isolde . In Berlin he devoted himself primarily to the performance of contemporary composers and founded the Berlin Tonkünstler Orchestra in 1901, but gave it up again after 2 seasons with 6 concerts each. Another focus of his activity were his efforts to improve the situation of artists and their social recognition. In 1901 he took over the chairmanship of the General German Music Association (ADM). He played a key role in founding the German Sound Composers Cooperative in 1903.

In 1905 Richard Strauss published his supplementary adaptation of Hector Berlioz's famous theory of instrumentation . His additions related to the change in instruments, such as in the case of the horn, and above all included the art of instrumentation in the works of Richard Wagner. Strauss himself knew how to create new timbres through clever instrumentation in his works .

The years in Berlin were also marked by numerous trips - including one to North America and a major trip to Greece and Italy - as well as the composition of other tone poems ( Ein Heldenleben , Sinfonia domestica , Eine Alpensinfonie ) and operas, some of which brought Strauss international triumphs, including alongside Feuersnot (1901) especially Salome (first performance 1905 in Dresden). During this time in Paris, Strauss met the poet and writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal , who, beginning with Elektra (premiered in Dresden in 1909), was to contribute the libretti for a total of six operas by the composer and who worked closely with Strauss.

In 1908 the composer moved into his newly built house in Garmisch . In 1910 the first Strauss Weeks took place in Munich, and later also in Dresden and Vienna. In 1911 Der Rosenkavalier was premiered in Dresden . In 1912 Ariadne auf Naxos was premiered in Stuttgart and the ballet Josephs Legende in Paris. Richard Strauss left Berlin in May 1918.

Maturity (1919–1944)

In 1919 Strauss took over the management of the Vienna Court Opera together with Franz Schalk , in which a little later he also performed his new opera Die Frau ohne Schatten .

Since 1917 Strauss (together with the set designer Alfred Roller and the conductor Franz Schalk ) had supported an initiative launched by the director Max Reinhardt and Hugo von Hofmannsthal to found festivals in Salzburg . Against all odds and regardless of the poor economic situation in Austria after the lost war, Strauss and his colleagues succeeded in realizing the first festival in 1920. In the first year only the play Jedermann was performed, concerts were added in 1921, and in 1922 Strauss conducted Don Giovanni, the first opera performance at the festival.

In 1924 Strauss ended his work as opera director in Vienna and was now able to devote himself entirely to conducting at home and abroad as well as to composition. The operas Intermezzo , Die Egyptische Helena , Arabella , Die Schweigsame Frau , Daphne , Friedensstag , Die Liebe der Danae and the last opera Capriccio were created .

After the takeover of the Nazis they managed to include the internationally known composers for their purposes. In April 1933 Strauss was one of the signatories of the “Protest of the Richard Wagner City of Munich” against Thomas Mann's essay The Sorrows and Greatness of Richard Wagner . On November 15, Strauss was appointed President of the Reich Chamber of Music . In Bayreuth he took over the management of Parsifal after Arturo Toscanini canceled his participation in protest. After Hindenburg's death , in August 1934, Strauss was one of the signatories of the call by cultural workers to confirm the amalgamation of the office of the Reich President and the Reich Chancellery .

By working with Stefan Zweig , who wrote the libretto for his opera Die Schweigsame Frau , Strauss fell out of favor with the National Socialists. After the Gestapo intercepted a critical letter to Stefan Zweig on June 17, 1935, Strauss was forced to resign as President of the Reichsmusikkammer. On the occasion of the 1936 Summer Olympics , Strauss composed the opening music for which he had been commissioned by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in Lausanne in 1932. On August 1, 1936, the Olympic anthem “Peoples! Be the people's guests ”based on a text by Robert Lubahn.

During the Second World War , Strauss dedicated a song to the Governor General of occupied Poland, Hans Frank , on November 3, 1943, for which he had also written the text. In August 1944, in the final phase of the Second World War, Strauss was not only placed on the God-gifted list by Hitler , but also on the special list with the three most important musicians.

Final years (1945–1949)

The last years of the composer's life were determined by illnesses and stays at health resorts. He retired to his house in Garmisch; after the end of the war he lived temporarily in Switzerland. Strauss did not have a permanent residence. He stayed with his wife in the "Beau-Rivage Palace" in Ouchy , in the "Montreux Palace" ( Montreux ), in the "Park-Hotel Vitznau" ( Vitznau ), in the "Saratz" in Pontresina or in the Baden "Verenahof" ( Baden AG ). The couple suffered from financial worries. Swiss friends such as the art patron Oskar Reinhart , Adolf Jöhr, Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt (SKA), Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille and the conductor Paul Sacher kept the couple afloat financially. In 1949 Strauss returned to Garmisch. His last compositions include the Metamorphoses for 23 solo strings , which premiered on January 25, 1946 in Zurich, the Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra and the Four Last Songs . On the occasion of a film on his 85th birthday, he conducted for the last time in the Munich Prinzregententheater (the finale of the second act of his Rosenkavalier ) and in July 1949 conducted an orchestra for the last time in the Munich Funkhaus (with the moonlight music from Capriccio ).

Richard Strauss died on September 8, 1949 at the age of 85 in Garmisch. A few days later there was a funeral service in the crematorium in Munich's Ostfriedhof . The urn was initially kept in his villa and many years later it was buried in close family and friends in a family grave at the Garmisch cemetery in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, where his wife Pauline, his son Franz, his daughter-in-law Alice and his grandson Richard were also buried were.

Work and appreciation

Richard Strauss composed 60-70 orchestral works (including those for solo instruments and symphonic poems), 70-90 chamber music compositions, over 200 songs, including at least 15 orchestral songs, 27 choral works and 15 operas.

Clay seals

Richard Strauss composed a total of 9 tone poems . He found models for his works in the program symphonies and symphonic poems by Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt , but above all in the symphonies and overtures of Ludwig van Beethoven . He explained his intention to his friend Romain Rolland in a letter:

"For me, the poetic program is nothing more than the form-creating occasion for the expression and the purely musical development of my feelings - not, as you believe, just a musical description of certain processes in life."

Operas

With his operas Salome and Elektra , Richard Strauss became famous all over the world as an opera composer. Based on Wagner's tonal language, he created a new dramaturgical expression, but did not leave the tonal basis. Later he changed his musical language and preferred a smoother musical style, in his later works even a more classical style. In addition to Salome and Elektra , Der Rosenkavalier , Ariadne auf Naxos , Die Frau ohne Schatten and Arabella have kept their repertoire .

Songs and late works

Richard Strauss left behind 220 songs, some with piano or orchestral accompaniment. 15 songs he composed in his childhood are currently lost. Among his best-known songs are the early Lieder, Op. 10, which he composed in 1885 when he was 21 years old. There are over 200 recordings of the first song attribution . He wrote many of his songs for his wife Pauline, with whom he often gave concerts.

An indispensable part of recitals are his four songs, Op. 27, rest my soul , morning (approx. 250 recordings), secret invitation and Cäcilie . His songs Heimkehr from op.15, the serenade from op.17, dream through the twilight from op.29, I carry my love from op.32, friendly vision from op.48, and the three so-called mother songs are sung again and again Birth of his son from op. 37, op. 41 and op. 43. His already expressionist song Notturno op. 44 was considered the epitome of modernity in 1899. His Krämerspiegel op. 66 against publishers and agents is something very special . Also to be mentioned are his “socialist songs” Blindenklage , Der Arbeitsmann and Das Lied des Steineklopfers .

In total, Strauss set ten poems by Karl Henckell to music , although he had to emigrate from Germany during the imperial era to Switzerland, four poems by the "anarchist" John Henry Mackay brought Strauss to world fame, 18 times Goethe is to be mentioned, 14 times Rückert (like Gustav Mahler ), 7 times Heine etc. Sketches remained his setting of the Rückert texts from 1935: “Away with deception and away with lies, away with the clever tricks of what politics means” and “So may God restore purity to life give". Politically noteworthy is also the dedication of his Goethe song Durch allen Schall und Klang from 1925 to his friend Romain Rolland , in which it says: "To the great poet and honored friend, the heroic fighter against all the nefarious powers working on Europe's downfall ... "

Richard Strauss also appeared as a choir composer. A total of 38 a cappella choral works and 13 compositions with accompaniment are available, including arrangements of folk songs for the so-called Kaiserliederbuch , initially for the folk songbook for male choir published in 1906 .

In 1948 he completed his last great work, Four Last Songs , for high voice and orchestra (premiered in 1950 by Kirsten Flagstad under Wilhelm Furtwängler in London), which are certainly his best-known song compositions. Strauss did not plan these songs as a cycle. His last completed composition was another song, Malven , finished on November 23rd. The score was only discovered in the estate of Maria Jeritza in 1982 . Malven was sung by Kiri Te Kanawa for the first time in 1985 and recorded in 1990 together with her second recording of Four Last Songs .

The last composition, contemplation for mixed choir and orchestra, based on the poem of the same name by Hermann Hesse ("Divine is and eternal the spirit ..."), remained a fragment.

The cultural politician

Richard Strauss also redefined the position of the musician in society. Although financially independent due to his maternal origin, he worked to ensure that composers can make a living from their work. This was by no means a matter of course in his time. Among other things, he demanded that a composer should be given a share of the income every time his music is performed. He assumed that composing is a civil profession and that the amount of his remuneration must therefore be comparable to the work of a lawyer or doctor. This view contradicted the previous role of the artist in society. Strauss therefore had to defend himself against the accusation that he was particularly business-minded and greedy, a view that has persisted to this day.

In order to achieve his goals, he joined Hans Sommer and Friedrich Rösch (1862–1925) in 1898 to establish a composers' association. According to Sommer's idea, works that are no longer protected by copyright should be subject to taxes and the income generated from this should go to young or distressed composers. Thus, on January 14, 1903, the German Tonsetzers' cooperative came into being, of which Strauss was one of the chairmen. On July 1, 1903, she founded the Institute for Musical Performance Law (AFMA) as a collecting society, a forerunner of GEMA .

Role in National Socialism

Strauss' role during the National Socialist era is controversial . According to some voices, he was completely apolitical and at no time cooperated uncritically with those in power. Others point out that as President of the Reich Music Chamber from 1933 to 1935 he was an official representative of National Socialist Germany.

When Bruno Walter was unable to give his fourth concert with the Berliner Philharmoniker in March 1933 because the new rulers did not like him as a Jew, Richard Strauss took his place to help the Jewish agency and the musicians, for whom he received his full fee left. He succeeded in having the concert poster read in bold letters: “Instead of Bruno Walter, Dr. Richard Strauss". Among other things, he conducted his Sinfonia domestica , "which (as Grete Busch tells in the biography of her husband Fritz ), in his own words, in the eyes of all decent people, caused him more damage than a German government could ever have done." Grete Busch was (so the biography continues) deeply disappointed that Strauss had left the world premiere of the opera Arabella Clemens Krauss after her husband had been chased away by the National Socialists. Strauss had promised the world premiere to Fritz Busch and the director Alfred Reucker , to whom he also dedicated the opera. In the eyes of the widow he broke his promise. But Strauss left the dedication and published it in the summer of 1933. He couldn't have done more. Strauss also stepped in when Arturo Toscanini canceled his participation in the Bayreuth Festival in 1933. At a cultural-political rally during the Reichsmusiktage in Düsseldorf on May 28, 1938, Richard Strauss conducted his Festive Prelude, which was composed in 1913 .

Strauss' daughter-in-law Alice was Jewish, so according to the racial ideology of the National Socialists, his grandchildren were also considered to be Jewish mixed race since the Nuremberg Laws (1935) . This may have been one reason why he refrained from open opposition - there were threats and reprisals from the regime in 1938, especially on the ground in Garmisch. On the occasion of the world premiere of the opera Die Schweigsame Frau in 1935, based on the libretto by the Jewish writer Stefan Zweig , the scandal finally broke out. Strauss showed courage and insisted that Stefan Zweig's name be printed on the program slip and on the posters - as in the case of Bruno Walter. Hitler stayed away from the performance in protest, and the regime dropped Strauss. The piece was stopped after three repetitions. However, the correspondence he received with Zweig during the affair shows that Strauss was not only willing to compromise in political matters, but was naive and instinctive. Strauss probably only fought for the artist Zweig, not against the political system. Zweig cautiously criticized Strauss, but expressed understanding that the 70-year-old composer believed that his own work and the well-being of his family and friends were more important than open resistance.

All in all, Strauss was highly valued by the National Socialist rulers, even if Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels considered him politically problematic, as here in his diary entry from June 5, 1935:

- “ Havemann dismissed because of a statement for Hindemith . Richard Strauss writes a particularly mean letter to the Jew Stefan Zweig. The Gestapo intercepts him. The letter is bold and silly too. Now Strauss has to go too. Quiet farewell. Keudell has to teach him. Politically speaking, these artists are all without character. From Goethe to Strauss. Away with it! Strauss 'mimes the music chamber president'. He writes that to a Jew. Ugh devil! "

The National Socialists included Strauss on the special list of the three most important musicians of the Third Reich . Because of his presidency in the Reichsmusikkammer, Strauss was automatically classified as the main culprit under the Denazification Act, but acquitted in 1948 as "not charged".

The Stefan Zweig affair is the subject of the play collaboration by Ronald Harwood and was also mentioned by Stefan Zweig himself in his work Die Welt von Gestern .

Quotes

“It's hard to write conclusions. Beethoven and Wagner could. Only the big ones can do it. I can do it too. "

Awards and honors

Richard Strauss received many honors throughout his life and became an honorary citizen of Munich , Dresden and Garmisch , among others . He also received an honorary doctorate from the universities of Heidelberg (1903), Oxford (1914) and Munich (1949) and became an honorary member of renowned orchestras. He received the Bavarian Maximilian Order and became an officer in the French Legion of Honor in Paris. In 1934 he received the eagle shield of the German Empire .

On December 16, 1942, he accepted the new Beethoven Prize from the City of Vienna, which Baldur von Schirach had awarded 10,000 Reichsmarks . He returned the favor with the composition of the festival music for the city of Vienna for brass and timpani, which he premiered on April 9, 1943 to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Anschluss with the Vienna Trumpet Choir.

The Richard Strauss Conservatory in Munich was named after him. He is also the namesake of Richard-Strauss-Straße in Munich. There are other streets named after him in Vienna , Bayreuth , Berlin , Eichstätt , Emden , Erlangen , Sarstedt and Richard-Strauss-Allee in Wuppertal and Frankfurt am Main. His former place of residence Garmisch-Partenkirchen named Richard-Strauss-Platz in the center of the village after him and built a Richard-Strauss fountain. The market town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen also operates the Richard Strauss Institute .

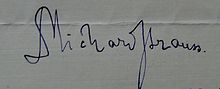

In 1992 the Austrian 500 Schilling commemorative coin Richard Strauss appeared in silver. On the front it shows the portrait of the artist and his name in the form of his signature. On the reverse is a scene from his opera Der Rosenkavalier .

A Richard Strauss Festival has been held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen every June since 1989, organized by the Richard Strauss Institute and sponsored by the Richard Strauss Festival Garmisch-Partenkirchen e. V . is supported.

In 1989 a rose variety was named after Richard Strauss. Together with the Austrian composer Johann Strauss (1804–1849), he has been the eponym for Mount Strauss on Alexander I Island in Antarctica since 1961 .

Deutsche Post issued a postage stamp in 2014 for his 150th birthday.

Works

AV ... Directory based on Erich Hermann Mueller von Asow , 1959

TrV ... Directory based on Franz Trenner , 1999

Clay seals

- From Italy op.16 (1886)

- Don Juan op.20 TrV 156 (1888)

- Macbeth op. 23 TrV 163 (1886–88, rev. 1889/90 and 1891)

- Death and Transfiguration op. 24 TrV 158 (1888–89)

- Till Eulenspiegel's funny pranks op. 28 TrV 171 (1894–95)

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra op. 30 TrV 176 (1896)

- Don Quixote - Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character, op.35 TrV 184 (1897)

- Ein Heldenleben op. 40 TrV 190 (1898)

- Sinfonia domestica op. 53 TrV 209 (1902-03)

- An Alpine Symphony op. 64 TrV 233 (1911–15)

as well as the fragment

- The Danube - Symphonic Poem for large orchestra, choir and organ AV 291 (1941)

Further orchestral compositions

- Symphony in D minor (1880)

- Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 8 (1881/82)

- Horn Concerto No. 1 in E flat major op.11 (1883)

- Symphony in F minor, op.12 (1883)

- Burlesque for piano and orchestra, D minor (1885/86)

- The Citizen as Nobleman, op. 60, orchestral suite (ballet suite) (1917/1920)

- Festive Prelude op.61 for large orchestra and organ for the opening of the Wiener Konzerthaus (1913)

- Parergon to the Sinfonia domestica op.73 for piano and orchestra (1925)

- Music for the silent film Der Rosenkavalier (orchestral arrangement) (1925)

- Panathenaic procession op.74 for piano and orchestra (1926/27)

- Japanese Festival Music (1940)

- Horn Concerto No. 2 in E flat major (1942)

- Concerto for oboe and small orchestra in D major (1945)

- Duet-Concertino for clarinet, bassoon and orchestra (1947)

- Festival music, occasional compositions, fanfares, suites

- Orchestra suites: instrumental extracts from stage works

Operas

- Guntram op.25. Libretto : Richard Strauss. Premiere in Weimar in 1894

- Feuersnot op. 50. Libretto: Ernst von Wolzüge . WP 1901 Dresden (conductor: Ernst von Schuch )

- Salome op. 54. Libretto: Richard Strauss, based on the play of the same name by Oscar Wilde , in German by Hedwig Lachmann . Premiere 1905 Dresden (conductor: Ernst von Schuch)

- Elektra op. 58. Libretto: Hugo von Hofmannsthal . Premiere 1909 Dresden (conductor: Ernst von Schuch)

- Der Rosenkavalier op. 59. Libretto: Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Premiere 1911 Dresden (conductor: Ernst von Schuch)

- Ariadne auf Naxos op. 60. Libretto: Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Premiere 1st version 1912 Stuttgart, 2nd version 1916 Vienna

- The woman without a shadow op. 65. Libretto: Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Premiere 1919 Vienna

- Intermezzo op.72.Libretto: Richard Strauss. Premiere 1924 Dresden

- The Egyptian Helena op. 75. Libretto: Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Premiere 1928 Dresden

- Arabella op.79.Libretto: Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Premiere 1933 Dresden

- The silent woman op. 80. Libretto: Stefan Zweig . Premiere 1935 Dresden

- Peace Day op. 81. Libretto: Joseph Gregor . Premiere 1938 Munich

- Daphne op.82.Libretto: Joseph Gregor. Premiere 1938 Dresden

- Die Liebe der Danae (1940) op.83.Libretto: Joseph Gregor. Premiere 1952 Salzburg

- Capriccio op.85.Libretto: Clemens Krauss . Premiere 1942 Munich

The musical comedy Des Esels Schatten based on Christoph Martin Wieland's Die Abderiten , composed 1947–1949, premiered in 1964, is usually not counted as an opera.

Ballet music

- Josephs Legende op. 63. Action in one act by Harry Graf Kessler and Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Premiere May 14, 1914 Paris

- Schlagobers op. 70. Libretto: Richard Strauss. Premiere May 9, 1924 Vienna

A cappella choirs

- Two chants op.34 for 16-part mixed choir (1897):

- No. 1: The evening ("Senke, radiant God"). Text: Friedrich Schiller

- No. 2: Hymn ("Jacob! Your prodigal son"). Text: Friedrich Rückert

- Two male choirs op.42 (1899). Texts: Johann Gottfried Herder , from: Volkslieder (1778, later: Voices of the peoples in songs )

- No. 1: Love ("There is nothing better on this earth")

- No. 2: Old German battle song ("Fresh up, you brave soldiers")

- Three male choirs op.45 (1899). Texts: Johann Gottfried Herder, from: Volkslieder (1778)

- No. 1: battle song ("There is no blessed death in the world")

- No. 2: Song of Friendship ("Man has nothing so special")

- No. 3: The bride dance ("dance that you give laws to our feet")

- A German motet (“The Creation has gone to rest”) op. 62 for 4 solos (SATB) and 16-part mixed choir (1913). Text: Friedrich Rückert

- Cantate (“The able-bodied makes quick luck high”) for 4-part male choir (1914). Text: Hugo von Hofmannsthal

- Three male choirs (1935). Texts: Friedrich Rückert

- No. 1: In front of the doors ("I knocked on the house of wealth")

- No. 2: Dream light ("A light in a dream has visited me")

- No. 3: Happy in May ("Blooming women, let yourself be seen")

- The goddess in the cleaning room (“What chaotic housekeeping”) for 8-part mixed choir (1935). Text: Friedrich Rückert

- Through solitude ("Through solitude, through wild game enclosure") for 4-part male choir (1938). Text: Anton Wildgans

- To the tree Daphne ("Beloved tree! From afar you wave"). Epilogue to Daphne (1943). Text: Joseph Gregor

Chamber music

- Introduction, theme and variations for horn and piano in E flat major AV 52 (1877)

- String Quartet in A major op.2 (1881)

- Cello Sonata in F major, Op. 6 (1880–1883)

- Serenade for 13 wind instruments in E flat major, Op. 7 (1881, WP 1882)

- Quartet for piano, violin, viola and violoncello in C minor op. 13 (1883–85)

- Violin Sonata in E flat major op. 18 (1887–1888)

- Andante for horn and piano op.posth. (1888)

- (First) Sonatina in F major. "From the workshop of an invalid" for sixteen wind instruments (1943)

- Second Sonatina in E flat major. "Happy workshop" for sixteen wind instruments (1944–1945)

Songs

- Eight poems from “Last Leaves” by Hermann von Gilm op. 10 (1885)

- Five songs op.15 (1886)

- Six songs by AF von Schack op. 17 (1886–87)

- Six songs from "Lotosblätter" by Adolf Friedrich Graf von Schack op. 19 (1888)

- Simple ways - Five poems by Felix Dahn op. 21 (1889–90)

- Girl Flowers - Four Poems by Felix Dahn op.22 (1888)

- Two songs based on poems by Nicolaus von Lenau op.26 (1891)

- Four songs op.27 (1894)

- Three songs based on poems by Otto Julius Bierbaum op.29 (1895)

- No. 1: Dream through the twilight ("Wide meadows in twilight gray")

- Four songs by Carl Hermann Busse and Richard Dehmel op.31 (1895)

- Five songs op.32 (1896)

- We both want to jump AV 90 (1896)

- Four chants for one voice with accompaniment of the orchestra op. 33 (1896–97)

- Four songs op. 36 (1897–98)

- Six songs op.37 (1898)

- Five songs op.39 (1898)

- Five songs op.41 (1899)

- Three songs by older German poets, op.43 (1899)

- Two larger chants for a deeper voice with orchestral accompaniment op.44 (1899)

- Five poems by Friedrich Rückert op.46 (1900)

- Five songs ( Ludwig Uhland ) op.47 (1900)

- Five songs based on poems by Otto Julius Bierbaum and Karl Henckell op.48 (1900)

- Eight songs op.49 (1901)

- Two songs op.51 (1902/06)

- Six songs op. 56 (1903-06)

- Krämerspiegel - Twelve Songs by Alfred Kerr op.66 (1918)

- Six songs op.67 (1918)

- Six songs based on poems by Clemens Brentano op.68 (1918)

- Five Little Songs (based on poems by Achim von Arnim and Heinrich Heine ) op. 69 (1918-19)

- Motto AV 105 (1919)

- Through all sound and sound AV 111 (1925)

- Chants of the Orient - Adaptations from Persian and Chinese by Hans Bethge op.77 (1928)

- Four songs op. 87 (1929–35)

- Three songs op.88 (1933/42) - No. 1: Das Bächlein

- Xenion AV 131 (1942)

- Mallow AV 304 (1948)

- Four last songs AV 150 (1948)

Marches and fanfares

- Parade march (No. 1) of the regiment Königs-Jäger on Horseback AV 97 (1905)

- Parade march (No. 2) for Cavalry AV 98 (1907)

- De Brandenburgsche Mars (Free adaptation of an older presentation march) AV 99 (1905)

- Military festival march (King's March) AV 100 (1906)

- Ceremonial entry of the Knights of the Order of St. John (Investiture March) AV 103

- Olympic Anthem (People! Be the People's Guests) AV 119 (1934)

- Wiener Fanfare (Fanfare of the City of Vienna) AV 134

- Festival March (D major) AV 178 (1886)

Other works (selection)

- Three hymns based on Friedrich Hölderlin (1921)

- Piano music

- Piano Sonata in B minor op.5

- Intermezzo for piano four hands, TrV 138 (1885 - first published posthumously in 2009)

- Enoch Arden , melodrama based on Alfred Tennyson's poem for speaking voice and piano (1897)

- The castle by the sea , melodrama based on Ludwig Uhland's poem o.op. 92 (1899)

- The Danube AV 291 TrV 284 (fragment for large orchestra, choir and organ) (1941–42)

- Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings (1945), commissioned by Paul Sacher , premiered January 25, 1946 in Zurich

The works have been in the public domain in Germany since January 1, 2020.

literature

- Eugen Schmitz : Richard Strauss as a music dramatist; an aesthetic-critical study. In: ebooks.library.cornell.edu. Publishing house Dr. Heinrich Lewy, Munich, 1907, accessed December 26, 2018 .

- Program book for the symphony concerts, winter 1907/08. Meinhold & Sons, Dresden 1907.

- Theodor Wiesengrund-Adorno : Richard Strauss. (sic) / 60th birthday: June 11, 1924. In: Zeitschrift für Musik , year 1924, issue 6 (June), p. 289ff. (Online at ANNO ).

- Willy Brandl: Richard Strauss. Life and work. Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden 1949.

- Willi Schuh (Ed.): Richard Strauss. Reflections and memories. Atlantis 1949 and 1981, ISBN 3-7611-0636-X .

- Veronika Beci : The eternally modern. Richard Strauss 1864-1949 . Droste, Düsseldorf 1998, ISBN 3-7700-1099-X .

- Michael Heinemann , Matthias Herrmann and Stefan Weiss (eds.): Richard Strauss. Essays on life and work. Laaber 2002, ISBN 3-89007-527-4 .

- Monika Reger: Strauss, Richard. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 5, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-7001-3067-8 .

- Ernst Krause : Richard Strauss - shape and work

- E. Krause: Richard Strauss - The last romantic

- Mathieu Schneider : Destins croisés. You rapport entre musique et littérature dans les œuvres symphoniques de Gustav Mahler et Richard Strauss. Edition Gorz, Waldkirch 2005, ISBN 3-938095-02-4 .

- Julia Liebscher: Richard Strauss and the music theater . Henschel, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89487-488-0 .

- Günter Brosche : Richard Strauss: Work and Life . Edition Steinbauer, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-902494-31-3 .

- Benedikt Stegemann: Orpheus, the sounding opera guide. Episode 5: Richard Strauss, Ricordi, Munich, 2009, ISBN 978-3-938809-55-6 .

- Raymond Holden: Richard Strauss: a musical life . Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, Conn. [u. a.] 2011, ISBN 978-0-300-12642-6 .

- Bryan Gilliam: Richard Strauss. Magician of sounds. A biography. CH Beck, Munich, 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66246-1 .

- Walter Werbeck: Strauss, Richard. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 25, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-428-11206-7 , pp. 516-519 ( digitized version ).

- Laurenz Lütteken : Richard Strauss: Musik der Moderne , Stuttgart: Reclam, 2014, ISBN 978-3-15-010973-1 .

- Michael Jahn : Richard Strauss and the Opera in Vienna 1 , Vienna: The Apple, 2014, ISBN 978-3-85450-323-1 .

- Daniel Ender : Richard Strauss: Master of Staging , Vienna: Böhlau, 2014, ISBN 978-3-205-79550-6 .

- Michael Walter : Richard Strauss and his time , 2nd edition, Laaber-Verlag 2015, ISBN 3-921518-84-9 .

- International Richard Strauss Society (ed.): Richard Strauss Yearbook . Hollitzer, Vienna 2015ff, ISSN 2190-0248.

Documentaries

- 1949: Richard Strauss - A life for music. Documentary, Federal Republic of Germany, 15 min., Book: Alfred H. Jacob, director: Werner Jacobs , production: Continent Film.

- Movie dates. In: filmportal.de . Retrieved December 26, 2018 .

- 1970: “Omnibus” - Dance of the Seven Veils on YouTube , accessed December 26, 2018 (Director: Ken Russell ).

- 1984: Richard Strauss Remembered. Documentary, UK , 120 min., Written and directed by Peter Adam , produced by BBC , BR and others.

- Movie dates. In: bfi.org.uk. BFI , accessed December 26, 2018 .

- 2014: Richard Strauss and his Heroines. (Alternative title: Richard Strauss und seine Heldinnen. ) Documentary, Germany, 51:20 min., Script and direction: Thomas von Steinaecker , production: SRF , Arthaus u. A.

- Table of contents. In: arthaus-musik.com. Arthaus, archived from the original on July 14, 2014 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- 2014: Christian Thielemann - My Strauss. Documentary, Germany, 45 min., Written and directed: Andreas Morell, production: 3B-Produktion, Unitel Classica , ZDF , 3sat , first broadcast: June 8, 2014 on 3sat.

- Table of contents. 3sat, archived from the original on June 12, 2014 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- 2014: Richard Strauss - Sketch of a Life. Documentary, Austria, 51:30 min., Script and direction: Barbara Wunderlich and Marieke Schroeder, production: ORF , series: matinee, first broadcast: June 9, 2014 on ORF 2 . Strauss' descendants tell about Richard Strauss, presentation of the Strauss archive in Garmisch.

- Table of contents. In: tv.orf.at. Austrian Broadcasting Corporation, archived from the original on June 13, 2014 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- 2014: Richard Strauss: The controversial musical genius. Documentary, Germany, 53 min., Written and directed by Reinhold Jaretzky , production: Zauberbergfilm, MDR , arte , first broadcast: June 11, 2014 on arte.

- Table of contents. In: arte.tv. arte, archived from the original on June 14, 2014 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- 2014: Richard Strauss - A musical border crosser. Documentary, Germany, 29:40 min., Written and directed by Reinhold Jaretzky , production: Zauberbergfilm, MDR , series: CVs, first broadcast: June 12, 2014 on MDR. (Editing by Richard Strauss: The controversial musical genius with a focus on Meiningen and Dresden.)

- Table of contents. ARD , archived from the original on August 20, 2014 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- 2014: Richard Strauss - the misunderstood visionary. An alpine symphony between tradition and modernity. Documentary, Germany, 50 min., Script and direction: Christoph Engel and Dietmar Klumm, production: 3sat , first broadcast: June 14, 2014 on 3sat. With Stefan Mickisch , the Huberbuam , Manfred Trojahn , Marlis Petersen and others.

- Table of contents. ARD, archived from the original on July 14, 2014 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- 2014: Richard Strauss - At the end of the rainbow. Documentary film, Austria, 97:30 min., Script and direction: Eric Schulz , production: ServusTV , first broadcast: August 14, 2014 on ServusTV. With Brigitte Fassbaender , Stefan Mickisch , Klaus König , Raymond Holden, Christian Strauss, Walter Werbeck, Emma Moore and others.

- Table of contents. ServusTV, archived from the original on August 16, 2014 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

Web links

Works by Richard Strauss

- Works by and about Richard Strauss in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Richard Strauss in the German Digital Library

- Literature by and about Richard Strauss in the Saxon Bibliography

-

Richard Strauss Institute Garmisch-Partenkirchen. In: richard-strauss-institut.de. Retrieved December 26, 2018 .

- Literature by and about Richard Strauss (reception and reception history). Archived from the original on August 2, 2012 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- Gerhard Schön: Online database Richard Strauss Bibliography (RSQV). In: rsi-rsqv.de. June 3, 2016, accessed December 26, 2018 .

- Markus Hillenbrand: Klassika: Richard Strauss (1864-1949). In: Klassika.info. September 8, 1949, accessed on December 26, 2018 (complete catalog raisonné by opus number, genre, year of creation).

- Richard Strauss works. Critical edition. In: richard-strauss-ausgabe.de. Retrieved December 26, 2018 .

- Sheet music and audio files by Richard Strauss in the International Music Score Library Project

- Strauss estate . OCLC 869872675 .

- Song portal. In: gmg-bw.de. Retrieved December 26, 2018 .

- Newspaper article about Richard Strauss in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Literature and performances

- Edited letters from and to Richard Strauss in the web service correspSearch of the BBAW

- Janca Imwolde, Lutz Walther: Richard Strauss. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Literature on Richard Strauss. In: Bibliography of the music literature . Retrieved December 26, 2018 .

- Profile, works, performances. In: de.schott-music.com. Schott Music , accessed December 26, 2018 .

- Website from Strauss' descendants about Richard. In: RichardStrauss.at. Strauss' descendants, accessed on December 26, 2018 (not entirely objective, but very informative).

- Richard Strauss. In: WagnerOpera.net. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Walter Werbeck: The tone poems by Richard Strauss . Schneider, Tutzing 1996, ISBN 3-7952-0870-X .

- ^ Rainer Franke: Article "Guntram", in: Piper's Enzyklopädie des Musiktheater , ed. by Carl Dahlhaus and the Research Institute for Music Theater at the University of Bayreuth under the direction of Sieghart Döhring, Volume 6. Piper, Munich and Zurich 1997, pp. 78–81.

- ↑ Michael Kennedy: Richard Strauss . Schirmer Books, New York 1976, pp. 22 .

- ^ Ernst Klee : The cultural lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-10-039326-5 , p. 598.

- ^ A b c Ernst Klee: The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 599.

- ↑ Heiner Wajemann, The choral compositions by Richard Strauss , S. 174th

- ^ Ernst Klee: The culture lexicon for the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, p. 598.

- ↑ Jürg Schoch: "Forgive the eternal plague ..." - how Richard Strauss harnessed the Swiss elite for himself after the Second World War. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of September 9, 2019

- ^ Richard Strauss / Works, section Symphonic poetry and orchestral works. Retrieved April 26, 2019 .

- ^ Richard Strauss / Works, Section Other Instrumental Works, Chamber Music, Piano Music. Retrieved April 26, 2019 .

- ↑ a b article Richard Strauss . In: Meyers Taschenlexikon Music in 3 volumes . tape 3 , 1984, ISBN 3-411-01998-0 .

- ↑ a b Richard Strauss / Works, section songs. Retrieved on April 26, 2019 (recounting resulted in 213 songs, 15 of them with orchestra and 2 melodrams).

- ↑ Works | Richard Strauss. Retrieved on April 26, 2019 (counting the titles in the Choral Works section results in 27, a total of approx. 45 choirs).

- ^ Richard Strauss / Works, section operas. Retrieved April 26, 2019 (recounting resulted in 16 operas, since Ariadne on Naxos is counted twice as op. 60 (1) and op. 60 (2)).

- ↑ Jürgen May: "[...] the direct line?" Richard Strauss as Beethoven's successor . In: Richard-Strauss-Blätter , New Series, Issue 58. Vienna 2007, pp. 9–16.

- ↑ Hans-Christoph Mauruschat: Those who trade with music. Hans Sommer, Richard Strauss and the fight for composers' rights. In: new music newspaper. 2000, accessed on December 26, 2018 (49th volume, edition 7/00).

- ↑ Maria Stader : Take my thanks. Memories. Retold by Robert D. Abraham. Munich 1979, p. 146. ISBN 3-463-00744-4

- ↑ See also his personal dedication shortly after his appointment as President of the Reich Chamber of Music of a copy by Joseph Gregor: Weltgeschichte des Theater . Phaidon, Zurich 1933: “To the noble friends and patrons / of the theater / Mr. Reich Chancellor / Adolf Hitler / admirably presented by / DRichard Strauss. // Christmas 1933. ”(JA Stargardt, Antiquarian Bookshop: Catalog 695th auction on April 19 and 20, 2011, p. 302, no. 616).

- ↑ Degenerate Music. For the 1938 exhibition in Düsseldorf . An annotated reconstruction, ed. by Albrecht Dümling and Peter Girth. Düsseldorf 1988, ISBN 3-924166-29-3 , p. 9.

- ^ Alois Schwarzmüller: Garmisch-Partenkirchen and its Jewish Citizens - 1933–1945. 2006, archived from the original on April 14, 2011 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- ↑ Joseph Goebbels Diaries , Ed. Ralf Georg Reuth , Piper 2008, ISBN 978-3-492-25284-3 .

- ^ Elisabeth Schumann: Diary entry of October 31, 1921. In: In Amerika with Richard Strauss. Elisabeth Schumann's diary. October 14 to December 31, 1921. December 31, 1921, archived from the original on July 19, 2011 .

- ↑ Bryan Gilliam: Richard Strauss. Magician of sounds. A biography. CH Beck, Munich 2014. ISBN 978-3-406-66246-1 .

- ↑ Program of the Berliner Philharmoniker , No. 70, 2010/2011 season from May 5, 6 and 7, 2011.

- ^ Richard-Strauss-Straße in the Vienna History Wiki of the City of Vienna

- ↑ Complete list of Schilling coins from 1947 to 2001, page 35, Austrian National Bank OeNb PDF. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014 ; accessed on December 26, 2018 .

- ^ Richard Strauss Festival. In: richard-strauss-festival.de. Retrieved December 26, 2018 .

- ^ Richard Strauss Festival Sponsors' Association. In: richard-strauss-foerderkreis.de. Retrieved December 26, 2018 .

- ↑ Ulrich Mosch (ed.): Paul Sacher, Facets of a musical personality. Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel 2006, p. 264, ISBN 3-7957-0454-5 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Strauss, Richard |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Strauss, Richard Georg (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German composer and conductor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 11, 1864 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Munich |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 8, 1949 |

| Place of death | Garmisch-Partenkirchen |