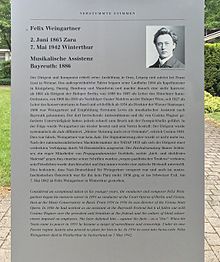

Felix Weingartner

Paul Felix Weingartner, Edler von Münzberg (born June 2, 1863 in Zadar , Austrian Empire ; died May 7, 1942 in Winterthur ) was an Austrian conductor , composer , pianist and writer .

Life

Weingartner studied in Graz , Leipzig and finally with Franz Liszt in Weimar . He was also a student of Carl Reinecke . Weingartner usually divided his work between conducting and artistic administration. He was also a composer and writer.

After Weingartner held several leading positions in Mannheim and Berlin , he was chief conductor of the Kaim Orchestra , today's Munich Philharmonic, from 1898 to 1905 . His opera Orestes , designed as a trilogy, was premiered in Leipzig in February 1902. In 1908 he took over the directorate of the Vienna Court Opera from Gustav Mahler for three years . From 1908 to 1927 Weingartner was director of the Vienna Philharmonic Concerts. From 1919 to 1924 he was director of the Vienna Volksoper .

On October 9, 1905, he was one of the first pianists to record 6 pieces for Welte-Mignon , in addition to Beethoven's Sonata No. 30 his own compositions from the past , Op. 3 and loose leaves , Op. 4th

One work from this period is his Sextet for Piano and Strings, Op. 33 from 1906.

In 1927 Weingartner went to Basel . Until 1934 he was also chief conductor of the then Basel orchestra , artistic director of the Allgemeine Musikgesellschaft and director of the conservatory, and he also made a number of guest appearances at the Stadttheater Basel . From 1935 to 1936 he was director of the Vienna State Opera . Weingartner also worked in Hamburg , Boston and Munich . Weingartner emigrated from Austrofascist Austria to Switzerland in 1936.

Although Weingartner composed a relatively large amount, his works can hardly be heard today. As a conductor, he shaped generations of musicians with his striking and elegant striking technique .

Music lovers became aware of his work again when the classical record label cpo released many first recordings between 2005 and 2010 , including his seven symphonies with the Basel Symphony Orchestra , the violin concerto and three string quartets.

Weingartner notated his scores in C (sounding) from around 1910. Small flute and double bass / contrabassoon he continued notating in octaves; for the horns he used the octaved treble clef, but this did not prevail. Sergei Prokofjew , Arthur Honegger and later Alban Berg and Arnold Schönberg did the same. Older works by Weingartner are traditionally notated - with the usual transpositions.

Felix Weingartner was in his first marriage (1891) with Marie Juillerat, in his second marriage (1902) with Feodora von Dreifus, in his third marriage (1912) with the singer Lucille Marcell , in his fourth marriage (1922) with the actress Roxo Betty Kalisch and in fifth marriage (1931) married to the conductor Carmen Studer .

Weingartner's remains were buried in the Rosenberg cemetery in Winterthur .

anecdote

A Viennese Kapellmeister asked Felix Weingartner, who was very famous in the interwar period, how quickly one had to play Beethoven's 5th Symphony . Felix Weingartner replied: “Sir, I'll be playing this work next Sunday. Come to the Musikverein , you will hear the right tempo there. "

At the Basel Carnival he was called the garden wailer: his fifth wife was 24, he was 68 years old, which is why he was given the telephone number 24 5 68 (verbal communication from an old choir singer).

Works

Operas

- Sakuntala (1884)

- Malawica (1885)

- Genesius (1892)

- Orestes (1901)

- Cain and Abel (1913)

- Lady Leprechaun (1914)

- The village school (1918)

- Master Andrea (1918)

Orchestral works

- 7 symphonies (opp. 23, 29, 61, etc.)

- Symphonic poems (King Lear, op.20, The Fields of the Blessed, op.21, Spring op.80)

- Serenade, op.6

- To Switzerland, op.79

- Funny overture, op.53

- Sinfonietta, op.83

- Violin Concerto in G major, op.52

- Cello Concerto in A minor, op.60

among others

Chamber music

- 2 violin sonatas, op.42

- Piano pieces (7 sketches, op. 1, sound images, op. 2, loose leaves, op. 4)

- 5 string quartets, opp. 24, 26, 34, 62 & 81

- 2 string quintets, op. 40 &?

- 1 piano quintet, op.50

- 1 piano sextet, op.33

- 1 octet

Over 100 songs, some choral works

Fonts

- The doctrine of rebirth and musical drama. 1895

- About conducting . 1896 or 1905

- “Bayreuth” 1876–96, a report. (initially W. worked there under Richard Wagner and later under Cosima Wagner's direction as an assistant and then as a conductor)

- The symphony after Beethoven . Leipzig 1897

- Advice on performing classical symphonies . 3 volumes, 1906–1923

- Chords (collected essays) . 1912

- Life memories . 2 volumes, Zurich 1923/29 (first reprint from January 1, 1919 in Neue Wiener Journal)

- Bô Yin Râ. The pictures and ornamental leaves of this book are from the hand of Bô Yin Râ . Rhein-Verlag, Basel, Leipzig 1923

- Rudolf Louis. The German music of the present .

- Emil Krause. Felix Weingartner as a creative artist . Berlin 1904

Note on the scriptures

Of the numerous books that Felix Weingartner wrote, only his advice on performing classical symphonies was known to other music circles. The first volume dealing with Beethoven was published in 1906 and translated into English as early as 1907. The second volume - Schubert and Schumann - did not appear until 1918 and was only translated into English in 1972 - through Asher G. Zlotnik's dissertation. The third volume went largely unnoticed. Here Weingartner treats Mozart . Apart from the first volume, which had a fourth edition in 1958, the other volumes were never offered as reprints, although there are reprints in the USA

First of all, it must be said that he gives advice that many can identify with. Whether he went further in his own performances would have to be checked on the basis of his scores, which are in his estate - now kept in Basel. They are the only retouches that are accessible to everyone at any time - free of charge. All others are either privately owned or only available from the publisher as expensive rental material - as with Gustav Mahler .

His advice regarding Beethoven is still regarded today as a classic handout from a great conductor, which contains a great deal of timelessly important information and is still used with pleasure. Weingartner never demands that all of his advice be followed - but he does show how to avoid these cliffs in known, difficult places. The only thing that is really controversial today is the horn retouche in the Scherzo of the Ninth Symphony , which goes back to ideas from Wagner.

The band that treats Schubert and Schumann still divides the music world today. He assumes a large orchestra that doubles the woodwinds - and also the horns. With Schubert he only deals with the Unfinished Symphony and the Great Symphony in C major . Only in the C major symphony does he show some effective retouches that Bruno Walter , Karl Böhm and George Szell used. The unfinished is well explained and only in a few places is it recommended that the woodwinds and the bass trombone be shifted to the lower octave.

His advice to Schumann was generally welcomed at the time and - what he wanted to achieve - led to an increased interest in his symphonies. Generations of conductors have followed them, and George Szell and Ernest Ansermet always played the second and fourth symphonies in his version. Weingartner is very sensitive here, he deliberately leaves many of Schumann's peculiarities, even if there are more clever solutions. The timpani, e.g. B., which Schumann often lets play wrong notes because his orchestras did not yet have pedal timpani that could be quickly changed - and here he proceeds like young Verdi - he always leaves it unchanged. (Many other conductors have used and modified the possibilities of the modern timpani.)

As a rule he lets the timpani and the winds - here especially the brass (trumpets / trombones) - pause in bars in order to achieve a clearer structure; and to loosen up the sound a bit. He also removes some doubling - mostly of the wind instruments - from harmony notes. Basically, he does what Schumann had also done in those places that are technically successful. Because not every work by Schumann has the same instrumental clumsiness, which can also be explained by his often very unstable psyche. So his advice is very different depending on the work:

He considers the first symphony to be quite successful; he leaves it with dynamic retouching, precise designation and individual pauses in the wind instruments. He explains the rhythmic relations between the individual sections, often peculiarly noted, especially in the Scherzo, very cleverly, and a contemporary copy of the first symphony that Niels Wilhelm Gade used, quoted by Asher G. Zlotnik in his dissertation , shows the same solution; but notated here differently.

He considers the instrumentation of the second symphony to be rather clumsy, but this only affects the corner movements. Here he takes a very radical approach and cuts entire passages. As with all other symphonies, the middle movements remain almost unchanged, apart from dynamic additions.

The Third Symphony , which was retouched significantly massive by many other conductors, he describes how the first symphony dynamically exactly are numerous breaks for wind and recommends high passages of the first (old) -Trombone that time - 1918 - almost had completely disappeared to allot the trumpet. His sensitivity is also noticeable here. (He even leaves the inaudible imitation of the theme in the clarinets and bassoons [first movement, A, bars 8 ff.], Which is often reinforced with horns, original.) Even "wrong" timpani tones remain at the end of the exposition. The middle movements are almost unchanged, only slightly thinned out.

With the fourth symphony he proceeds in a similar way, one has the feeling that he must have known exactly the original form from 1841, which turned out to be far more transparent - and was therefore preferred by Johannes Brahms . He seems to have adopted many details as a suggestion for this version. Here, too, he explains the rhythmic relationships between the individual sections.

Weingartner assumes the orchestra around 1910, which, however, remained much more similar to the orchestra in Schumann's day than the orchestras were from around 1975. The length of the brass section was much narrower, they sounded considerably quieter and the string sound was different. The wood wind schools were also very different from region to region. Weingartners repeatedly demands clarity and more clarity in his explanations, which also corresponds to the playing tradition of the early Romantic and Classical periods. Seen in this way, he only does what the representatives of historical performance practice are doing today, although they often refuse to retouch.

literature

- Ingrid Bigler-Marschall: Felix Weingartner . In: Andreas Kotte (Ed.): Theater Lexikon der Schweiz . Volume 3, Chronos, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-0340-0715-9 , p. 2065 f.

- Walter Jacob (ed.): Felix von Weingartner. A breviary for the 70th birthday . Westdruckerei Spett, Wiesbaden 1933.

- Simon Obert, Matthias Schmidt (ed.): In the measure of modernity. Felix Weingartner - conductor, composer, author, traveler . Verlag Schwabe, Basel 2009, ISBN 978-3-7965-2519-3 .

- Stefan Schmidl: Weingartner, Felix. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 5, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-7001-3067-8 .

- Felix Weingartner in the Vienna History Wiki of the City of Vienna

- Weingartner, Felix , in: Werner Röder; Herbert A. Strauss (Ed.): International Biographical Dictionary of Central European Emigrés 1933-1945 . Volume 2.2. Munich: Saur, 1983 ISBN 3-598-10089-2 , p. 1223

Documents

Letters from Felix Weingartner to the two Leipzig music publishers and copies of letters to him (in the publishers' letter copying books) are in the holdings of 21070 CF Peters, Leipzig, and 21081 Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig, in the Leipzig State Archives .

Web links

- Felix Weingartner's estate in the Basel University Library

- Literature by and about Felix Weingartner in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Felix Weingartner in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Christoph Ballmer: Felix Weingartner. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gerhard Dangel and Hans-W. Schmitz: Welte Mignon Reproductions / Welte Mignon Reproductions. Complete catalog of recordings for the Welte-Mignon Reproducing Piano 1905–1932 / Complete Library Of Recordings For The Welte-Mignon Reproducing Piano 1905–1932 . Stuttgart 2006. ISBN 3-00-017110-X . P. 504

- ↑ Robert Teichl, Paul Emödi (ed.): Who is who. Lexicon of Austrian contemporaries . Vienna 1937, p. 372.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Weingartner, Felix |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Weingartner, Paul Felix; Weingartner Edler von Münzberg, Paul Felix (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian conductor, composer, pianist and writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 2, 1863 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Zadar |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 7, 1942 |

| Place of death | Winterthur |