Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , who mostly signed with Wolfgang Amadé Mozart (born January 27, 1756 in Salzburg ; † December 5, 1791 in Vienna ), was a Salzburg musician and composer of the Viennese classical music . His extensive work enjoys worldwide popularity and is one of the most important in the repertoire of classical music.

Life

The child prodigy (1756–1766)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born on January 27 , 1756 at eight o'clock in the evening in Salzburg at Getreidegasse 9 in a three-room apartment in an apartment building ( Hagenauerhaus ) and was named Joannes Chrysostomus the next morning at ten o'clock in Salzburg Cathedral by city chaplain Leopold Lamprecht Wolfgangus Theophilus was baptized and entered in the baptismal register (his father Leopold Mozart used the name form Joannes Chrisostomus Wolfgang Gottlieb ). He was called Wolferl , Wolfgang or Woferl . The Wolferl was the seventh child of his parents, but only the second to survive. His siblings were Johannes Leopold Joachim (* 1748, died in the sixth month of life), Maria Anna Cordula (* 1749, was six days old), Maria Anna Nepomucena Walburga (* 1750, died in the third month of life), Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia - the Nannerl (* 1751, was 78 years old), Johann Baptist Karl Amadeus (* 1752, was not quite three months old) and Maria Crescentia Franziska de Paula (* 1754, died in the second month of life). His father was from Augsburg to study at the Benedictine University drawn (1622-1810) to Salzburg, Prince Bishop chamber musician (from 1757 court composer and from 1763 assistant music) Leopold Mozart, his mother in St. Gilgen grown Anna Maria Pertl .

At the age of four, he and his sister Maria Anna Mozart , who was five years older than him , received their first music and general education lessons in piano, violin (→ Mozart's children's violin ) and composition from their father . As early as 1761, Leopold's father recorded an andante and an allegro as the “Wolfgangerl Composition”, followed by an allegro and a menuetto , dated December 11th and 16th, 1761. The minuet in G major, wrongly mentioned again and again as the earliest composition with a minuet in C major as a trio KV 1 was probably not composed until 1764. Mozart's talent for piano and violin also quickly emerged. His first appearances followed in 1762.

The first concert tours of Wolfgang and his sister Nannerl with their parents were arranged to Munich in early 1762 and from Passau to Vienna in autumn 1762 in order to present the talented children to the nobility. After the success of the Wunderkind siblings in Munich and Vienna, the family embarked on an extensive tour of Germany and Western Europe on June 9, 1763, which lasted three and a half years until they returned to Salzburg on November 29, 1766. Stops were Munich, Augsburg, Ludwigsburg , Schwetzingen , Heidelberg , Mainz , Frankfurt am Main , Koblenz , Cologne , Aachen , Brussels , Paris (arrival on November 18, 1763), Versailles , London (arrival on April 23, 1764), Dover , Belgium , The Hague (September 1765), Amsterdam , Utrecht , Mechelen , again Paris (arrival May 10th 1766), Dijon , Lyon , Geneva , Lausanne , Bern , Zurich , Donaueschingen , Ulm and Munich, where the children were at court or in public academies made music. During these trips he wrote the first sonatas for piano and violin as well as the first symphony in E flat major (KV 16). The four sonatas for piano and violin KV 6 to 9 are Mozart's first printed compositions in 1764.

During this trip, Mozart was introduced to the Italian symphony and opera in London . There he also met Johann Christian Bach , who became his first role model. In 1778 Mozart wrote from Paris after seeing him back home: "I love him (as you probably know) with all my heart - and I have great respect for him."

First compositions in Vienna and the trip to Italy (1766–1771)

After returning home, the first world premieres followed in Salzburg, including the school opera The Duty of the First Commandment , which the eleven-year-old Mozart had composed with the much older Salzburg court musicians Anton Cajetan Adlgasser and Michael Haydn . A second family trip to Vienna followed in September. To avoid the rampant smallpox epidemic , they drove to Brno and Olomouc . The disease reached Wolfgang and his sister there and left (according to several biographies) scars on Wolfgang's face. After the children's convalescence, Mozart returned to Vienna on January 10, 1768, where he completed the Singspiel Bastien und Bastienne (KV 50), the orphanage fair (KV 139) and the opera buffa La finta semplice (KV 51). Although ordered by the German Emperor Franz I , the latter could not be performed; The reason was the intrigues of the so-called "Italian party" around the court manager Giuseppe Affligio.

Between 1767 and 1769 Mozart stayed repeatedly in the Benedictine monastery Seeon . As late as 1771, he was still performing offers there . Mozart wrote two offers especially for the Seeon Abbey: Scande coeli limina (KV 34; 1769) and Inter natos mulierum (KV 72; 1771). The so-called “Mozarteiche”, under which, according to tradition, he was happy to sit, is still growing today at Seeoner See.

After 15 months in Vienna, Mozart and his family returned to Salzburg on January 5, 1769. It was here that La finta semplice was finally performed on May 1st, and it was here that on October 27th, when he was appointed third concertmaster of the Salzburg court orchestra, he was given his first, albeit unpaid position.

Almost three weeks later, on December 13, 1769, Mozart and his father set off on his first of three extremely successful trips to Italy , which lasted almost three and a half years - with interruptions from March to August 1771 and December 1771 to October 1772.

The first trip took her to Verona , Milan , Bologna , Florence , Rome , Naples , Turin , Venice , Padua , Vicenza , Innsbruck and back to Salzburg . Mozart recovered here until autumn, after which he started a longer (third) stay in Milan. Pope Clement XIV made him Knight of the Golden Spur in Rome in 1770 , but, unlike Gluck , he never made use of the privilege of calling himself a “knight”. In Rome, he succeeded after only once or twice a nine-part Miserere by Gregorio Allegri had listened, the backbone of the Vatican top secret score flawlessly write down from memory. It is not clear to what extent the singers colored voices improvising and whether Mozart was able to write it down. The original of this transcription has not survived and more recent studies provide understandable explanations for this apparently inexplicable achievement. Writing was made easier by the repetitive structure of the piece.

Mozart studied counterpoint with Padre Giovanni Battista Martini in Bologna . After an exam he was accepted into the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna . There he met such important musicians as Giovanni Battista Sammartini , Niccolò Piccinni , Pietro Nardini and Giovanni Paisiello . On December 26, 1770 he saw the world premiere of his Opera seria Mitridate, re di Ponto (KV 87) in Milan, the success of which led to two further commissions: the Serenata teatrale Ascanio in Alba (KV 111, world premiere in Milan on October 17, 1771 ) and the Dramma per musica Lucio Silla (KV 135), premiered in Milan in the 1772/73 season. On December 15, 1771, father and son returned to Salzburg after hopes for a job in Italy had not been fulfilled.

Concertmaster in Salzburg (1772–1777)

In 1772 Hieronymus Franz Josef von Colloredo was elected Prince Archbishop of Salzburg; he succeeded the late Sigismund Christoph Graf von Schrattenbach . In August, Mozart was appointed concertmaster of the Salzburg court orchestra by the new prince. Nevertheless, this did not lead to the end of his many journeys with his father. Wolfgang continued to try to escape the strict regulations of the Salzburg service: From October 24, 1772 to March 13, 1773, the third trip to Italy followed for the world premiere of Lucio Silla , during which the result , jubilate , came about, and from mid-July to mid-July September 1773 the third trip to Vienna. In the same year he wrote his first piano concerto . From October 1773, the Mozart family lived on the first floor of the dance master's house , which had previously belonged to the Salzburg court dance master Franz Gottlieb Spöckner (approx. 1705–1767).

After a long break, a trip to Munich followed on December 6, 1774 for the premiere of the opera buffa La finta giardiniera (KV 196). On January 13th, 1775 and after his return on March 7th, Mozart tried again to establish himself as an artist of music in Salzburg. For example, he had the dramma per musica Il re pastore premiered in Salzburg on April 23, 1775, which, however, did not go down well with the public. After several unsuccessful requests for leave, he submitted his resignation to the Prince Archbishop in 1777 and asked to be released from the Salzburg court orchestra.

Looking for a job and again in Salzburg (1777–1781)

After his dismissal from the service of the prince, Mozart went on a city trip with his mother on September 23, 1777; he was trying to find new and better employment. At first he auditioned in vain at the Bavarian electoral court in Munich, then in Augsburg and at the court of Mannheim's elector Karl Theodor , where he met the electoral orchestra and its conductor, his future friend Christian Cannabich (see also Mannheim School ). But even here he got neither a job nor any musical commissions. But he got to know the Weber family and their daughter Aloisia , a young singer and later Munich prima donna , with whom he fell in love.

After five months in Mannheim, he and his mother, urged by their father, drove on to Paris, where they arrived on March 23, 1778. Mozart was able to perform his ballet music Les petits riens there, but received no further engagements. On July 3, 1778, his mother died at 10 o'clock in the evening. The young Mozart then lived for a few months in an apartment of Baron Melchior Grimm , where Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges had also lived for two years.

The return trip to Salzburg, which he reluctantly started three months later on September 26, to take up the vacant position of court organist, took him via Strasbourg , Mannheim and Kaisersheim to Munich, where he met the Weber family again. He did not reach his hometown until mid-January 1779 and was appointed court organist on January 17th. Here he composed the later so-called Coronation Mass (KV 317).

This renewed attempt with an engagement in Salzburg went reasonably well for 20 months, although the relationship with the archbishop remained tense, as he forbade him to participate in lucrative concerts in Vienna. On another trip on November 5, 1780, he took part in the very successful world premiere of his Opera seria Idomeneo (KV 366) on January 29, 1781 in Munich . Afterwards Mozart took part in the academies of the Salzburg court musicians on behalf of the archbishop. After two violent arguments with the Archbishop and a “kick” by his Count's envoy, the Prince Archbishop's Chief Kitchen Master Karl Joseph Maria Graf Arco - Mozart himself reports on the Count's “kick” in his letters - there was a final break. On June 8, 1781, Mozart resigned from his service in Salzburg, settled in Vienna and made his living there for the next few years through concerts in private and public academies.

Freelance composer in Vienna (1781–1791)

Freed from the Salzburg “shackles”, the now independent composer and music teacher, who was constantly on the lookout for clients and piano students and who was not afraid to work “in stock”, created the really great operas and a large number of piano concerts, which he usually performed himself.

- On July 16, 1782, the Singspiel (in German!) The Abduction from the Seraglio (KV 384) commissioned by Emperor Joseph II was premiered in Vienna. Years followed that were filled with composing and performing piano concertos and during which Mozart was doing very well financially.

- On May 1, 1786, the opera buffa Le nozze di Figaro (“Figaro's Wedding”, KV 492) was premiered in Vienna.

- On October 29, 1787, the premiere of the dramma giocoso Don Giovanni ("Don Juan", KV 527) in Prague

- The premiere of the opera buffa Così fan tutte (“This is how all women do it”, KV 588) in Vienna on January 26th, 1790

- (these last three after libretti by Lorenzo Da Ponte )

- On September 6, 1791, the opera seria La clemenza di Tito (“The Mildness of Titus”, KV 621) was premiered in Prague

- On September 30, 1791, the great opera Die Zauberflöte (KV 620) was premiered in Emanuel Schikaneder's theater in Freihaus on the Wieden. With that he returned to the German language. The story and texts of the Magic Flute go back to Emanuel Schikaneder and represent a speculative mixture of a previous work The Philosopher's Stone , a fairy tale by Wieland and Masonic attributes.

During this phase Mozart also composed the Great Mass in C minor (KV 427) (1783) and important instrumental works: the six string quartets dedicated to Joseph Haydn (KV 387, 421, 428, 458, 464, 465) (1785), the Linzers Symphony (KV 425), the Prague Symphony (KV 504) (1786) and the serenade Eine kleine Nachtmusik (KV 525) (1787) as well as the last three symphonies, in E flat major (KV 543, No. 39), G- Minor (KV 550, No. 40) and in C major, called the Jupiter Symphony (KV 551, No. 41).

In Vienna around 1782/83 Mozart met Gottfried van Swieten , a proven music lover and prefect of the imperial library, today's Austrian National Library . He introduced him to the manuscripts of Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Handel , which he had collected in Berlin, at the regular Sunday concerts in van Swieten's rooms in the imperial library . The encounter with these baroque composers made a deep impression on Mozart and immediately had a great influence on his compositions.

On August 4, 1782, Mozart married Constanze Weber , a younger sister of Aloisias . Mozart had met his wife three years earlier in Mannheim. In the following years they had six children: Raimund Leopold († August 19, 1783), Carl Thomas (* 1784 - October 31, 1858 ), Johann Thomas Leopold († November 15, 1786), Theresia Konstantia Adelheid Friderika (* 1787 ; † June 29, 1788), Anna Maria († November 16, 1789) and Franz Xaver Wolfgang (* 1791; † July 29, 1844 ). Only Carl Thomas and Franz Xaver Wolfgang survived their childhood.

The father Leopold Mozart , whom Wolfgang visited again in his Viennese years in 1783 and who visited him again in 1785, died on May 28, 1787.

The original publisher of Mozart was Heinrich Philipp Boßler, one of the most important music publishers of his time. The overtures Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni were published in Boßler's publishing house . Heinrich Philipp Bossler also worked as impresario for the gifted virtuoso Marianne Kirchgeßner, who composed the Adagio and Rondo for glass harmonica, flute, clarinet, viola and violoncello (KV 617) and the Adagio (KV 356 / 617a) for her glass harmonica playing Mozart . HP Bossler, who knew Mozart personally, had already made an engraving with the title Signor Mozart in 1784 . It was also impresario Boßler who published a detailed obituary for Wolfgang Amadé Mozart in 1792, addressing the poor situation of destitute children.

Through his friendship with Otto Heinrich von Gemmingen-Hornberg Mozart came to Vienna on December 14, 1784 Masonic Lodge to charity one. Mozart regularly visited a second Viennese lodge, Zur Wahr Eintracht , in which the Illuminatist Ignaz von Born was chairman . There he was promoted to journeyman on January 7, 1785. On February 11th, however, he could not be present at the initiation of his friend Joseph Haydn, because on the same evening that his father Leopold Mozart had also arrived from Salzburg, he gave the first of his six subscription concerts in the Mehlgrube and the solo part of his Played piano concerto in D minor, K. 466. In Mozart's instigation his father Leopold Mozart was a Freemason: This was inaugurated on Wednesday, April 6, 1785 in the building works of his son as a bricklayer apprentice and on 16 and 22 April 1785 again in the box to preserve harmony in the 2. resp. 3rd degree raised.

In his operas Die Zauberflöte and Le nozze di Figaro in particular, tones of social criticism can be felt from this membership, which may have contributed to the fact that Mozart was not doing so well financially after the world premiere of Figaro , especially since shortly after the unfavorable 8. Austrian Turkish War against the Ottoman Empire was waged. On December 7th, 1787 Joseph II appointed Mozart to the Imperial Chamber Musicus and provided him with an annual salary of 800 guilders , and on May 9th, 1791 as an unpaid adjunct of the cathedral music director of St. Stephen's Cathedral , Leopold Hofmann .

With the performance of Le nozze di Figaro in 1786, which Joseph II released despite its critical content, he overwhelmed the Viennese audience and withdrew from him. So his economic situation worsened without him taking this fact into account with his expenses. Despite the previous prosperity, he had not accumulated any savings and had to borrow money from friends several times. These failures led to a turning point in his life. During this time he only had success in Prague.

Apart from the Viennese public, he created the works of the last years of his life. He tried in vain to stop the economic downturn by traveling again. These trips took him to the performances from January 8th to mid-February 1787 and from the end of August to mid-September 1791 in Prague. From April 8 to June 4, 1789 he traveled with Prince Karl Lichnowsky via Prague, Dresden and Leipzig to Potsdam and Berlin to see the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm II. From September 23 to early November 1790 he traveled to the coronation of Emperor Leopold II. , who succeeded the deceased Joseph II, to Frankfurt am Main. Mozart and his friend, the theater director Johann Heinrich Böhm , stayed in the "Backhaus" at 10 Kalbächer Gasse . On his travels home he made stops in Mannheim and Munich.

But the trips to Berlin in 1789 and Frankfurt in 1790 did not help him to regain prosperity. In Berlin he received neither income nor employment. The opera Così fan tutte requested by the emperor was only moderately well received, as was the performance in Frankfurt am Main and the world premiere of La clemenza di Tito in Prague. Only the great applause for the Magic Flute promised economic improvement, but now it was no longer the nobility, but the "simpler" population, with whom it found a response.

Last works and early death

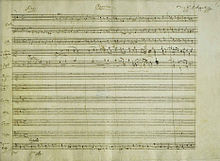

After the world premiere of La clemenza di Tito in Prague, Mozart returned to Vienna in mid-September 1791 and immediately threw himself into the work for the world premiere of The Magic Flute (KV 620), which took place two weeks later - again with success . At the same time he had worked out the motet Ave verum corpus (KV 618) and began writing the Requiem (KV 626), which he could no longer complete. Franz Xaver Süßmayr , according to Constanze Mozart a former student of Mozart, completed the Requiem.

A few weeks after the premiere of The Magic Flute on September 30, 1791, Mozart was bedridden on November 20 (about two days after he had conducted the world premiere of his cantata Loud proclaim our joy , KV 623) In the morning he died. He wasn't quite 36 years old. During the last year of his life he lived in the Kleiner Kayserhaus , which until the middle of the 19th century was at Rauhensteingasse 8 on the back of today's Steffl department store ( Kärntner Straße 19). A memorial plaque reminds us that Mozart died there on December 5, 1791.

As a cause of death was determined by the Totenbeschauer called "hitziges Frieselfieber" (most likely "the combination of a high fever disease course with a visible rash"). As a result, various other causes of death were considered: on the one hand, various viral , bacterial and parasitic infectious diseases such as syphilis and, possibly in connection with this, the then common use of mercury , trichinellosis , pharyngitis or an infection with streptococci , which lead to a cross-reaction against streptococci directed antibodies against heart inner skins - and work led, called rheumatic fever , whereupon then possibly leading to death an aortic developed. In addition, diseases such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura , kidney failure , heart failure or the consequences of bloodletting performed several times, most recently on December 3, are mentioned. Mozart himself was convinced that he had been poisoned and said to Constanze a few weeks before his death during a visit to the Prater: “Certainly, I was given poison.” However, there is no documented evidence of a poisoning.

After his body had initially been laid out in the apartment in accordance with the regulations, Mozart was buried in a general grave at the Sankt Marxer Friedhof . The funeral was organized by Gottfried van Swieten. Mozart's widow only visited the grave for the first time after 17 years. In 1855 the location of his grave was determined as well as possible and in 1859 a tomb was erected at the presumed location, which the City of Vienna later transferred to the group of musicians' honorary graves at the Central Cemetery (32 A-55). On the old, vacated grave site, a Mozart memorial plaque was erected again on the initiative of the cemetery attendant Alexander Kugler, which over time was converted from spoils of other graves into a tomb and is now a much-visited attraction.

Financial circumstances and legacies

The thesis of the “impoverished genius Mozart” comes from Romanticism . Every biographer tried to “make Mozart even poorer”. The cliché of “poor Mozart” is still widespread, especially among the public, while recent research rejects it. Mozart was certainly not rich compared to a count or a prince, but he was rich compared to the other members of his class, the fourth class of citizens.

By today's standards, Mozart was a big breadwinner, but due to the way he lived, he was often in financial straits. For an engagement as a pianist he received according to his own statements "at least 1000 guilders " (for comparison: he paid his maid one guilder per month). Together with his piano lessons, for which he charged two guilders each, and his income from concerts and performances, he had an annual income of around 10,000 guilders, which corresponds to around 125,000 euros based on today's purchasing power. Nevertheless, the money was not enough for his lavish lifestyle, so that he often enough asked others, such as Johann Michael Puchberg , a lodge friend, for money. He lived in large apartments and employed a lot of staff, and he had a certain passion for card and billiards games , which could have made him lose large sums of money. According to the estate register, the most valuable individual item in his legacy was not the numerous valuable books or musical instruments in his possession, but rather his expensive clothing. Mozart did not die in poverty because he still had a loan and Anton Stadler even had a loan of 500 guilders outstanding. His pool table, which was a luxurious status symbol at the time, bears witness to Mozart's very high living conditions in 1791.

Mozart's funeral

The facts

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart died on Monday, December 5th, 1791, at around one o'clock in the morning in his house in Vienna.

- He was laid out on the same day in his apartment and on December 6th by the crucifix chapel on St. Stephen's Cathedral built over the entrance to the catacombs . The farewell was celebrated among his friends and relatives.

- According to the observatory in Vienna , which kept weather records, the weather was mild and dry. However, this is not an indication of the road conditions in December 1791.

- According to the Vienna City and State Archives, it is not known whether Mozart was brought to the Sankt Marxer Friedhof on December 6, 1791 in the evening or early in the morning on December 7, 1791 . There is no record of this. According to a sanitary ordinance valid at the time, a burial would not have been allowed until December 7th.

- Mozart was laid in a "common simple grave". The designation of graves was not forbidden due to the Josephine reforms of August 1788, but was not done in the case of Mozart.

The speculation

- Mozart died impoverished and was buried in a poor grave:

- It is wrong that he died penniless. Rather, it is correct that he was buried in a "simple general grave", not in a "mass grave" . However, it is also correct that Mozart's widow was only able to settle the remaining debts and cover the family's livelihood for some time because she received a pension from Emperor Leopold II and the profit from a benefit concert, for which the emperor himself gave a generous amount, were awarded.

- Mozart would not have been buried at the St. Marx cemetery, but at the Matzleinsdorf cemetery :

- With reference to contemporary memories of Salieri, Gall and the Aschenbrenner brothers, it was published that the blessing and burial of Mozart's body did not take place until December 7, 1791 during a massive onset of bad weather and that there are indications of a burial at the Matzleinsdorf cemetery. The funeral procession should not have passed through the Stubentor (in the direction of St. Marx) , but through the Kärntner Tor in the direction of the Matzleinsdorfer Friedhof; the information originally valid for this cemetery about the location of the grave is said to have been applied later to the St. Marx cemetery. Mozart is also said to have been laid out in Schikaneder's Freihausheater . At that time the St. Marxer Friedhof was outside the city, Mozart was not a citizen of the city of Vienna.

- Nobody would have accompanied Mozart's funeral procession to his grave:

- It is true that the funeral procession was not accompanied by friends and relatives to the Sankt Marxer Friedhof. It is wrong that this happened because of the weather conditions. Rather, it is correct that at that time in Vienna accompanying the corpse to the actual grave, which in Mozart's case was four kilometers away, was unusual. With the funeral ceremony in St. Stephen's Cathedral, the funeral ceremonies planned at that time came to an end.

- Mozart's body would have been reburied:

- It was not until 17 years after Mozart's death that his wife Constanze tried to find her husband's grave. However, since there was no cross or designation of this grave, one had to rely on the highly uncertain memories of the cemetery employees. It is therefore not possible to state where Mozart was buried.

- The real skull of Mozart is kept at the International Mozarteum Foundation (ISM) in Salzburg:

- For the first time, experts were able to carry out a DNA analysis and a chemical test on the skull. The reference material required for the DNA analysis came from skeletons that had been recovered from the Mozart family grave in the St. Sebastian cemetery in Salzburg. Leopold Mozart is not buried in this grave, but in the communal crypt. The result published in January 2006 therefore provided no evidence of the authenticity of the skull due to the lack of comparative material. In April 1991, Walther Brauneis , who had been asked by the ISM to deal with the historical facts, found the manuscript with the title “Mozart's skull is found” (1868) in the Vienna library in the “Vorordinate Nachlass von Ludwig August Frankl ”. Frankl's description of the so-called Mozart skull was known, but it was not known that Hyrtl had attested Frankl's text. According to this, the skull differs considerably from the one kept by the ISM: Seven teeth are named for the "Frankl / Hyrtl skull", while the ISM's skull has eleven teeth. This proves that the skull kept in the ISM cannot be identical to the "Frankl / Hyrtl skull".

Medical speculation

The Danish neurologist and psychiatrist Rasmus Fog speculated in 1985 about a possible illness of Mozart with Tourette's syndrome . In 2005, the Irish professor of child and adolescent psychiatry Michael Fitzgerald examined the question of whether Mozart had Asperger's Syndrome in his publication The Genesis of Artistic Creativity . Based on the biographical material, he thinks it is entirely possible. Because of Mozart's hyperactivity and impulsiveness, a diagnosis of ADHD could also be correct.

The first legends about the causes of death began to circulate shortly after Mozart's death. For example, mercury poisoning or motives for murder of his competitor Antonio Salieri are alleged.

Mozart's first name

On January 28, 1756 - one day after his birth - Mozart was baptized with the name Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus (different spelling of his first names: Joannes Chrisostomus Wolfgang Gottlieb .) The first and last of the given names refer to the godfather Joannes Theophilus Pergmayr, Senator et Mercator Civicus , the first two names at the same time on the saint of the day Johannes Chrysostomos , the middle first name Wolfgang on Mozart's grandfather Wolfgang Nicolaus Pertl. Mozart later translated the Greek Theophilus (“ Gottlieb ”) into its French equivalent Amadé or (rarely) Latinized Amadeus .

His nickname was Wolfgang all his life . During his travels in Italy he often called himself Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart. As an adult, he usually signed as Wolfgang Amadé Mozart, if not just as Wolfgang Mozart at all (for example, he signed the attendance list of the Viennese Masonic lodge Zur Charity ). He called himself Amadeus in three of his letters in jest. The form of the name Wolfgang Amadeus only appeared officially once during Mozart's lifetime, namely in the spring of 1787 in an official letter from the Lower Austrian Lieutenancy. The first posthumous official mention of Mozart with the Latinized first name is the entry in the death examination protocol of the Viennese magistrate on December 5, 1791.

Mozart's letters

Starting in his adolescence, Mozart wrote numerous letters during his life, which made it possible to get to know his personality and his musical views and ways of working, thus providing an important basis for research into Mozart's life and work. The most important correspondent by letter was Mozart's father Leopold Mozart.

Mozart's travels

Mozart spent a total of more than ten years, almost a third of his life, on journeys that took him to ten countries in what is now Europe. The carriage rides alone - a trip from Salzburg to Vienna, for example, took about six days, depending on the season and the weather - were a physical challenge at the time. In addition, the Mozarts often traveled in winter. On December 29, 1762, Leopold Mozart wrote about the trip from Preßburg to Vienna to Lorenz Hagenauer, the landlord and simultaneous patron of the Mozarts in Salzburg:

"[...] we did not travel particularly comfortably that day, as the road, although gutted, was just indescribably button-tight and full of deep pits and bumps; den̄ the Hungarians make no way. If I hadn't had to buy a wagon in Pressburg that was well hung, we would certainly have brought home a few fewer ribs. I had to buy the car if I wanted otherwise, that we should come to Vienna in good health. In the whole of Presburg no four-seater closed wagon was to be found with all country coaches. A coachman had this wagon - the coachmen are not allowed to drive overland, recorded with 2 horses only for several hours. "

How uncomfortable he experienced the journey from Salzburg to Munich, Wolfgang Amadeus describes in a letter to his father on November 8, 1780:

“My arrival was happy and cheerful! - happy because nothing adverse happened to us on the journey, and happy because we could hardly wait for the moment to get to the place and the end, because of the short but very arduous journey; - because, I assure you that none of us was able to sleep for just a minute through the night - this car pushes your soul out! - and the seats! - hard as stone! - From Wasserburg, I actually believed that I would not be able to bring my bottom all the way to Munich! - It was very difficult - and I guess I was fiery - I drove two whole posts with my hands on the upholstery and keeping my buttocks in the air - but enough of that, that’s already over! - but it will be my rule to go on foot rather than drive in a mail van. "

Mozart's instruments

Although some of Mozart's early keyboard works were written for harpsichord, in his early years he also got to know fortepiani by the Regensburg piano maker Franz Jakob Späth . Later, when Mozart visited Augsburg, he was very impressed by Johann Andreas Stein's fortepiani , as he told his father Leopold in a letter. On October 22nd, 1777 Mozart performed his 7th Piano Concerto (KV 242) for the first time on instruments provided by Stein. The Augsburg cathedral organist Demmler played the first, Mozart the second and Stein the third. In 1783 Mozart bought a fortepiano from Walter in Vienna . In a letter, Leopold Mozart confirms his son's close bond with Walter's fortepiano: “It is impossible to describe the hectic pace. Your brother's piano has been taken from his home to the theater or someone else's home at least twelve times. "

Mozart's nationality

The question of the composer's citizenship or national team is answered differently in the history of reception. Since the late 14th century, Salzburg had been the capital of the essentially independent archbishopric of Salzburg , which was spiritually subordinate to the Holy See in Rome, and secularly as part of the Bavarian Empire to the Roman-German Emperor (during Mozart's lifetime it was Franz I , 1745–1765 , 1765 –1790 Joseph II and 1790–1792 Leopold II ), but not the “Austrian” Habsburg monarchy . His father Leopold came from a Swabian family that had lived in Augsburg for generations, and his mother Anna's family is based in the Salzburg area , although this did not result in any citizenship in the modern sense for Wolfgang. Mozart was born in the archbishopric as a subject of the prince-archbishops and remained so all his life. Mozart's nationality could therefore be described as "(Prince Archbishop) Salzburg (er) isch", but this description of his country team is less common. The widely used Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians describes Mozart as an Austrian composer. The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography (2003), the Oxford Concise Dictionary of Music (Bourne and Kennedy 2004) and the NPR Listener's Encyclopedia of Classical Music (Libbey, 2006) also refer to it as such. The Encyclopædia Britannica provides two different results: The short, anonymous version in Micropedia describes him as an Austrian composer; the main article in Macropedia , written by HC Robbins Landon , does not deal with his nationality. In earlier sources, Mozart is often referred to as a German, especially before the founding of today's modern Austrian nation-state. A London newspaper reported on the composer's death in 1791. There he is (English: as "the celebrated German composer" the celebrated German composer ), respectively. In Lieber et al. (1832, p. 78), Mozart is presented as "the great German composer". Ferris (1891) included Mozart - alongside Frédéric Chopin , Franz Schubert and Joseph Haydn , among others - in his book The Great German Composers . Other designations than German can be found in Kerst (1906, p. 3), Mathews and Liebling (1896), and MacKey and Haywood (1909); much later also with Hermand and Steakley (1981). Some sources changed their assignments of Mozart to today's states in the course of time. Grove did not always refer to Mozart as an "Austrian"; this first appeared in the first edition of New Grove in 1980. It was similar with Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians . Originally they did not mention Mozart's country team. The word "Austrian" was first mentioned in the opening sentence in the eighth edition of 1992 and has been retained ever since. The Encyclopædia Britannica , which today calls him "Austrian", previously described him as a German composer.

Mozart himself did not comment on the question of his “citizenship” in the modern sense in his posthumous writings, but calls himself Teutscher , for example in letters to his father, e. B. of May 29, 1778, in which it says: "But what gives me the most uplifting and good courage is that I am an honest German" - and of September 11, 1778, in which he writes: "I am just sorry that I'm not staying here to show him that I don't need him - and that I can do as much as his Piccini - although I'm only a German. ”In a letter of August 17, 1782 he writes: Will Germany, my beloved fatherland, of which I am (as you know) proud, does not accept me, then, in God's name, France or England must get rich again by one more skilled German - and that to the shame of the German nation.

From this it becomes evident that for him Teutschland as a designation for the German-speaking areas of Central Europe and the Teutsche Nation (each in the spelling customary in Upper Germany at the time) as a collective of German-speaking people living there were conceptual reality without the nation-state concept of our time being applied to it could find: In his time there was no legal entity called “Germany” or one called “Italy”, which he writes about elsewhere. What did exist, however, was the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation , which included today's Germany and Austria. He wrote music for the emperor in Vienna at the time the above statement was made, after he had moved from Salzburg the year before and got married. This thus forms the context for understanding the statement about one's self-location.

progeny

- Raimund Leopold Mozart (born June 17, 1783 in Vienna; † August 19, 1783 ibid)

- Carl Thomas Mozart (born September 21, 1784 in Vienna, † October 31, 1858 in Milan )

- Johann Thomas Leopold Mozart (born October 18, 1786 in Vienna; † November 15, 1786 ibid)

- Theresia Maria Anna Mozart (* December 27, 1787 in Vienna; † June 29, 1788 ibid)

- Anna Maria Mozart (born November 16, 1789 in Vienna; † November 16, 1789 ibid)

- Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart (born July 26, 1791 in Vienna; † July 29, 1844 in Karlsbad )

His two childhood survivors died childless. There are therefore no more direct descendants of Mozart.

Memory of Mozart

overview

The memory of Wolfgang A. Mozart and the preoccupation with his work is maintained today through biographies, musicological research, radio and television broadcasts, symposia and, in particular, through performances of his compositions in opera houses and concert halls. Since the 19th century - especially in Austria and Germany - Mozart years have been celebrated in all round commemorative years .

The Republic of Austria immortalized Mozart on coins or banknotes several times, for example on the 5000 Schilling banknote from 1989 and the Austrian 1 euro coin. In 2006, in honor of his 250th birthday, the Federal Republic of Germany issued a 10 euro silver coin with the image of Wolfgang A. Mozart. In this way, according to the official justification, the personality of the composer should be preserved for posterity as a great event “from German culture and history”. In addition, Deutsche Post AG issued a special stamp on the same occasion.

There are also a number of merchandising items (e.g. Mozart balls ).

Austrian 1 euro coin (2002)

ÖBB advertising locomotive for its 250th birthday, 2006

Postage stamp (1956) of the Deutsche Bundespost for the 200th birthday

For places in his biography, Mozart's name means an important economic factor in the field of international city tourism . His birthplace Salzburg (Mozart monument on Mozartplatz ), Vienna as his long-term residence (Mozart statue in the Burggarten ) and the city of Augsburg as the birthplace of his famous father Leopold Mozart play a special role . Prague was one of Mozart's favorite venues. That is why it is very popular here too. A bust was erected in the Walhalla in his honor .

In several cities there are Mozart memorials that take on the memory of the composer in a special way. The same applies to Mozart societies and clubs . The first monument to the composer, a pavilion adorned with frescoes called Mozart's temple , was erected by a private admirer in Graz in spring 1792 .

In honor of Mozart, an asteroid discovered in 1924 was named (1034) Mozartia and a mineral discovered in 1991 was named Mozartite . In addition, the Mozart Piedmont Glacier off the west coast of the Antarctic Alexander I Island bears his name. The plant genus Mozartia Urb. from the myrtle family (Myrtaceae) is named after him.

Festivals

Numerous festivals deal mainly with Mozart's works. As early as the 19th century, a number of Mozart festivals took place in his hometown. The most important contemporary festivals include (the date of foundation in brackets):

|

|

A characteristic of almost all of these festivals is that Mozart represents their central axis, but mostly compositions by other composers are also performed. There are also regular Mozart festivals in Bath , Texas and Vermont .

Salzburg

In the Getreidegasse , the former taught International Mozart Foundation (which in 1870 lasted until 1879) in the birthplace of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (→ Hagenauer House ) is a museum. Another Mozart Museum is located in the apartment that the Mozart family moved into in 1773 in the Tanzmeisterhaus on Makartplatz . In 2006 the rooms were redesigned by the director and designer Robert Wilson . Ludwig Schwanthaler's Mozart monument on Mozartplatz faces the Old Residence and Cathedral and was unveiled in 1842. The planning and financing of the project shows how much Mozart was not only understood as a local patriotic Austrian, but also as a cross-class property for all Germans: the plans were mainly made up of non-Salzburgers, and among the financial sponsors you can find Emperor Ferdinand I. the kings of Prussia and Bavaria, the nobility as well as civil music associations and prominent musicians.

A bronze statue of Mozart is on the Kapuzinerberg . This was unveiled on the occasion of the First International Mozart Festival in 1877, a forerunner of the Salzburg Festival , and was created by Edmund Hellmer . The Magic Flute House , in which Mozart allegedly composed The Magic Flute , was also placed behind the statue. The operator of these campaigns was the Mozart enthusiast Johann Evangelist Engl (1835–1925), to whom the foundation of the Mozarteum Foundation goes back and who also had the Mozart's “show grave” built. The Mozart sculpture “ Mozart - A Hommage ” by Markus Lüpertz , which was set up in 2005 on Ursulinenplatz in front of the Markuskirche , led to controversy for a while.

The International Mozarteum Foundation has its headquarters in Salzburg. It was founded in 1880 by the citizens of Salzburg and emerged from the Cathedral Music Association and Mozarteum , which was established in 1841 . The foundation's collection of autographs contains around 190 original letters by Mozart, and the Bibliotheca Mozartiana , with around 35,000 titles, is the most extensive relevant library in the world. The foundation also has a wealth of images, including several authentic Mozart portraits. The sound and film collection has around 18,000 audio tracks (including recordings of Mozart performances that are otherwise inaccessible) and around 1,800 video productions (feature films, television productions, opera recordings, documentaries ). The foundation also manages the two Mozart museums in Salzburg. The Central Institute for Mozart Research, founded in 1931 and now known as the Academy for Mozart Research , is anchored in the foundation's statutes . It organizes scientific conferences at regular intervals, which are reported on in the Mozart Yearbook . All areas of Mozart research are taken into account, but the central issue since 1954 has been the publication of the New Mozart Edition , the historical-critical edition of Mozart's works.

The foundation also owns the Mozarteum concert building with two halls. The Great Hall of the Mozarteum is not only used for Salzburg concerts, but is also regularly used by the Salzburg Festival - with matinees, song recitals, solo concerts and orchestral concerts. Every year in January the foundation has been organizing the Mozart Week since 1956 , in which renowned orchestras (such as the Vienna Philharmonic or the Mahler Chamber Orchestra ) and interpreters ( Nikolaus Harnoncourt , Riccardo Muti, etc.) perform Mozart's works, also in the Great Hall of the Mozarteum.

The Mozarteum Public Music School was also founded in 1880 , from which the Mozarteum University eventually developed. There training courses for string, wind, plucked and percussion instruments as well as training for acting are offered. The Mozarteum University is now located in the Neustadt in the Old Borromeo next to the Mirabell Gardens . The two Mozart orchestras in Salzburg initially developed from students at this institution :

The Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra has existed since 1908 (currently with 91 musicians), which today, as the orchestra of the city and state of Salzburg, is responsible for the opera and operettas of the Salzburg State Theater , as well as taking on important tasks at the Salzburg Festival: it has played Mozart's Great every year since 1950 Mass in C minor (KV 427) in the collegiate church of St. Peter , participates in opera productions , the Mozart matinees on Sunday mornings, serenades , orchestral concerts and festive events. The orchestra has its roots in the "Dommusikverein und Mozarteum" founded in 1841 and was brought into being with the help of Constanze Mozart .

The second Salzburg Mozart Orchestra is the Camerata Salzburg , which was founded in 1952 by Bernhard Paumgartner as the Camerata Academica of the Mozarteum Salzburg from teachers and students from the Mozarteum University. The aim of the Camerata was and is primarily to care for Mozart. Under her chief conductor Sándor Végh (1978–1997) she took over the Mozart matinees at the Salzburg Festival for many years and has since made guest appearances worldwide under the direction of well-known conductors such as Heinz Holliger , Kent Nagano , Trevor Pinnock and Franz Welser-Möst .

From the Mozart festivals of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Salzburg Festival finally developed from 1920 onwards, and Mozart has remained at its center since it was founded. Analogous to Bayreuth, which performs the works of Richard Wagner every year , the Salzburg genius loci should be honored every summer in exemplary performances. Around half of all opera productions at the Festival are dedicated to Mozart operas, the first opera performance at the Festival was Don Giovanni on August 14, 1922, conducted by Richard Strauss and sung by Claire Born , Gertrud Kappel , Lotte Schöne and Alfred Jerger , Viktor Madin , Franz Markhoff , Richard Mayr , Richard Tauber .

The Haus für Mozart in Hofstallgasse has been one of the venues for the Salzburg Festival since 2006 . The Great Winter Riding School originally stood here , which was adapted as a festival theater in 1925 for Max Reinhardt's drama productions . From 1927 onwards, operas - mostly Mozart's - were played every summer in this house, which was finally rebuilt several times. On the occasion of the upcoming 250th birthday of Mozart, the Festspielhaus was completely renovated between 2003 and 2006 and was given the new name. The opening took place on July 26, 2006 with a new production of Le nozze di Figaro . In this Mozart year , all of Mozart's other stage works were shown for the first time as part of the festival ( Mozart 22 project , see opera chronology of the Salzburg Festival ).

Vienna

One of Mozart's apartments in Vienna has been preserved, but without furniture that has been lost; it has been converted into a museum: Domgasse 5, right behind St. Stephen's Cathedral . The original memorial was expanded by two floors some time ago and reopened as Mozarthaus Vienna in January 2006 . Mozart's life and time are explained to the visitor through, in some cases, elaborate multimedia presentations. Commemorative plaques are attached to numerous other houses in which Mozart lived or performed.

The Mozart monument , designed by architect Karl König and sculptor Viktor Tilgner in 1896, stood on Albertinaplatz . After the Second World War , it was transferred to the Burggarten in 1953 . The sculptures are made of Lasa marble ( Vinschgau , South Tyrol), the steps of the base are made of dark diorite . The balustrades are made of coarse Marble from Sterzing in South Tyrol, two pillars that were added during the re-erection were made from St. Margarethen sand-lime brick .

In 1862 in Vienna- Wieden (4th district) Mozartgasse was named after the composer, in 1899 Mozartplatz ; In 1905 the Mozart fountain was built there. In January 2006, the Theater an der Wien , which in the previous decades had mainly housed musical productions, was rededicated again to an opera house on the occasion of the Mozart anniversary year. Mozart is still a focus of the programming of Vienna's New Opera House .

augsburg

In the Mozart House in the northern old town of Augsburg there is a memorial to the history of the Mozart family. His father Leopold was born in this house . A plaque on the house of the Augsburg Fuggerei (Mittelgasse 14) also commemorates his great-grandfather, the master bricklayer Franz Mozart (1649–1694), who lived and died here.

The German Mozart Society (DMG), based in Augsburg, “is dedicated to ... the practical and scientific maintenance of the work of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart, research into the life and work of the master and his family and the preservation and promotion of the Mozart memorials in the Federal Republic of Germany, especially the house where Leopold Mozart was born in Augsburg ”.

Mannheim

Mozart is also widely thought in Mannheim, where he not only spent 176 days of his life during four stays, but also composed a number of important works, conducted a performance of Le nozze di Figaro in 1790 and, during his first stay in 1777, went to Aloisia Weber in love as well as her sister Constanze , who later became his wife, got to know. The “ Mannheim School ” at that time was of European standing in terms of music history, but in the end Mozart could not succeed there professionally. There are memorial plaques at numerous places where the composer lived and worked, such as the palace , the Jesuit church and the Bretzenheim palace .

Prague

A Mozart Museum was set up in the so-called Vila Bertramka in the Smíchov district of Prague in 1956 . During Mozart's lifetime, the building was on the other side of the city wall and served as an estate for the family of the composer Franz Xaver Duschk . It belonged to the showerk's wife, the singer Josepha showerk , the granddaughter of Ignatz Anton von Weiser , the Salzburg mayor and lyricist Mozart. Mozart lived here in October 1787 (completion and world premiere of Don Giovanni ) and from the end of August to the beginning of September 1791 (preparation and world premiere of La clemenza di Tito ).

music

Joseph Haydn paid tribute to Mozart's music when he assured Leopold Mozart in 1785 after hearing the string quartets dedicated to him by Mozart for the first time:

"[...] I tell you before God, as an honest man, your son is the greatest composer I know personally and by name: he has taste, and about it the greatest science of composition."

Mozart himself confessed in a letter to his father dated February 7, 1778:

"Because, as you know, i can pretty much accept and imitate all types and styles of compostitions."

It is a verifiable peculiarity of Mozart that during all of his compositional periods he absorbed music of the most varied of styles and drew a variety of stimuli from it. His compositional style is essentially shaped by southern German and Italian stylistic elements from the second half of the 18th century. The earliest influences come from his father and the Salzburg local composers. The dispute over the two “Lambacher” symphonies, for which it was long unclear which was by Leopold Mozart and which by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, shows how closely Mozart initially remained attached to his surroundings.

During his travels to Italy he got to know the style of opera there, which had a strong influence on him and was also taught to him in London by Johann Christian Bach . The study of counterpoint had a great influence - especially on his later work - first through composition lessons with Padre Martini in Italy, later in Vienna through the practical examination of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Handel , which he studied with Gottfried van Swieten got to know. Mozart to his father on March 30, 1783: “Because we love to talk to all sorts of masters; - with old and with modern ”.

The following points can be mentioned as typical of Mozart's compositional work:

- Mozart gave the piano concerto genre symphonic qualities and brought it to perfection.

- More than his contemporaries, Mozart wrote a very differentiated and demanding orchestral setting, and the winds in particular achieved a previously unknown independence.

- As with Joseph Haydn, this goes hand in hand with an increase in the length and scope of the individual works (most clearly seen in the symphonies).

- Mozart integrated contrapuntal compositional techniques into his compositions and merged the classic homophonic and baroque polyphonic styles (finale of the string quartet KV 387, finale of the “Jupiter” symphony KV 551).

- His works are shaped by three compositional methods that characterize the Viennese Classic , which Mozart developed together with Joseph Haydn and which Beethoven developed further: obligatory accompaniment , openwork style and motivic-thematic work .

- Especially in his late operas, Mozart created a convincing psychological-dramaturgical character drawing.

- In his music, Mozart succeeded in combining the apparently easy and catchy with the musically difficult and demanding.

- Mozart composed "Music for all genre people [...] except for long ears not". (Mozart's letter of December 16, 1780)

All in all, thanks to his outstanding abilities, Mozart created music of great complexity and high level of style from the styles and composition techniques he found. Beethoven and the composers of the 19th century were able to build on this.

Interpretation style

Mozart's piano playing was praised and valued everywhere. It must be remembered that he did not play the modern piano , but the fortepiano and occasionally the harpsichord .

As a basic articulation, Mozart used the non legato customary at the time . This is testified by Ludwig van Beethoven, who heard him several times in concerts, and reproduced by Carl Czerny . Accordingly, Mozart had "a fine, but chopped-up game, not a ligato."

factories

Mozart's works are usually counted according to their sorting in the Köchel Index (KV), which tries to follow the chronological order in which they were created.

Operas

| year | title | KV |

|---|---|---|

| 1767 | The obligation of the first commandment | KV 35 |

| 1767 | Apollo et Hyacinthus | KV 38 |

| 1768 | Bastien and Bastienne | KV 50 |

| 1768 | La finta semplice | KV 51 |

| 1770 | Mitridate, re di Ponto | KV 87 |

| 1771 | Ascanio in Alba | KV 111 |

| 1771 | Il sogno di Scipione | KV 126 |

| 1772 | Lucio Silla | KV 135 |

| 1775 | La finta giardiniera / The gardener out of love | KV 196 |

| 1775 | Il re pastore | KV 208 |

| 1780 | Zaide (fragment) | KV 344 |

| 1781 | Idomeneo | KV 366 |

| 1782 | The abduction from the Seraglio | KV 384 |

| 1783 | L'oca del Cairo (fragment) | KV 422 |

| 1783 | Lo sposo deluso ossia La rivalità di tre donne per un solo amante (fragment) | KV 430 |

| 1786 | The director of the theater | KV 486 |

| 1786 | Le nozze di Figaro | KV 492 |

| 1787 | Il dissoluto punito ossia il Don Giovanni | KV 527 |

| 1790 | So fan tutte ossia La scuola degli amanti | KV 588 |

| 1791 | The Magic Flute | KV 620 |

| 1791 | La clemenza di Tito | KV 621 |

A total of 21 operas.

Church music

17 fairs , including

- 1768/69 - orphanage fair (KV 139)

- 1776 - Sparrow Mass (KV 220)

- 1776 - Missa in C major , Credo Mass or Spaur Mass (KV 257)

- 1776 - Missa brevis in C major , organ solo mass (KV 259)

- 1779 - Coronation Mass (KV 317)

- 1782 - Great Mass in C minor (KV 427 / 414a)

See the article: List of Mozart's Church Music Works

- 1766/67 - Oratorio The Duty of the First Commandment (KV 35)

- 1771 - Oratorio La Betulia liberata (KV 118)

- 1791 - Ave verum corpus (KV 618)

- 1791 - Requiem in D minor (KV 626)

-

Motets for soprano and orchestra, including

- 1773 - Exsultate, jubilate (KV 165)

- Cantatas

- 2 vespers

- 4 litanies

- 17 church sonatas

Orchestral works

Symphonies

See the list of Mozart's symphonies

Piano concerts

See list of Mozart's piano concertos

Works for string instruments and orchestra

See also violin concertos (Mozart)

- 1773 - Violin Concerto No. 1 in B flat major (KV 207)

- 1774 - Concertone for 2 violins in C major (KV 190 / 186E)

- 1775 - Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major (KV 211)

- 1775 - Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major (KV 216)

- 1775 - Violin Concerto No. 4 in D major (KV 218)

- 1775 - Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major (KV 219)

- 1776 - Adagio in E major (KV 261)

- 1776 - Rondo concertante for violin and orchestra in B flat major (KV 269 / 261a)

- 1778 - Concerto for Violin and Piano in D major (KV315f)

- 1779 - Sinfonia concertante for violin and viola in E flat major (KV 364 / 320d)

- 1779 - Sinfonia concertante for violin, viola and cello in A major (KV 320e)

- 1781 - Rondo in C major (KV 373)

A total of 12 works.

Works for wind instruments and orchestra

- 1774 - Bassoon Concerto in B flat major (KV 191 / 186e)

- 1777 - Oboe Concerto in C major KV 314

- 1778 - Sinfonia concertante for flute, oboe, horn and bassoon in E flat major (KV 297B), handed down as a version for oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon (KV 297b)

- 1791 - Clarinet Concerto in A major (KV 622)

Flute concerts and movements

- 1777 - Flute Concerto in G major (KV 313 / KV 285c)

- 1778 - Flute Concerto in D major (KV 314 / KV 285d)

- 1778 - Andante for flute and orchestra, C major (KV 315 / KV 285e)

- 1778 - Concerto for flute, harp and orchestra in C major (KV 299 / KV 297c)

Horn concerts and movements

- 1781 - Rondo for horn and orchestra in E flat major (KV 371)

- 1791 - Horn Concerto in D major (KV 412/514 / 386b)

- 1783 - Horn Concerto in E flat major (KV 417)

- 1786 - Horn Concerto in E flat major (KV 495)

- 1787 - Horn Concerto in E flat major (KV 447)

A total of 13 works.

Further orchestral works

Serenades

- 1773 - Serenade No. 3 in D major, "Antretter" (also: "Andretter") (KV 185 / 167a) (final music)

- 1774 - Serenade in D major (KV 189b)

- 1774 - Serenade No. 4 in D major, "Colloredo" (KV 203 / 189ba)

- 1775 - Serenade No. 5 in D major (KV 204 / 213a)

- 1776 - Serenade No. 6 in D major, "Serenata notturna" (KV 239)

- 1776 - Serenade No. 7 in D major, "Haffner" (KV 250 / 248b)

- 1776 - Serenade No. 8 in D major, "Notturno for four orchestras" (KV 286 / 269a)

- 1779 - Serenade No. 9 in D major, "Posthorn" (KV 320)

- 1782 - Serenade No. 10 in B flat major, "Gran Partita" (KV 361)

- 1781 - Serenade No. 11 in E flat major (KV 375)

- 1782 - Serenade No. 12 in C minor "Night Musique" (KV 388 / 384a)

- 1787 - Serenade No. 13 in G major, "A Little Night Music" (KV 525)

Notturni

- 1778 - Notturno for four orchestras in D major (KV 286)

Divertimenti

- 1772 - Divertimento in D major (KV 131)

- 1772 - Divertimento in D major (KV 136/125 a) - "Salzburg Symphony No. 1"

- 1772 - Divertimento in B flat major (KV 137/125 b) - "Salzburg Symphony No. 2"

- 1772 - Divertimento in F major (KV 138/125 c) - "Salzburg Symphony No. 3"

- 1783–85 - Divertimenti No. 1 to 5 in B flat major (KV 229 / 439b)

Marches

- 1769 - March in D major (KV 62)

- 1773 - March in D major (KV 167b)

- 1774 - March in D major (KV 189c)

- 1775 - March in D major (KV 213b)

- 1776 - March in D major (KV 249)

- 1779 - March in D major (KV 320a No. 1)

- 1779 - March in D major (KV 320a No. 2)

- 1769 - Cassation in B flat major (KV 62a)

- 1769 - Cassation in G major (KV 63) (final music)

A total of 23 works.

Chamber music

-

Chamber music works without piano

- String duos and trios

- String quartets

- String quintets

- Wind quartets

- Quintets with winds

- 1787 - Sextet A Musical Fun (KV 522)

-

Chamber music with piano

- 35 sonatas for violin and piano

- 6 piano trios

- 2 piano quartets

- 1784 - Piano quintet in E flat major (KV 452)

Piano music

See list of Mozart's piano music works

- 18 piano sonatas

- Variations on different themes

- numerous individual pieces: fantasies , rondos, etc.

Organ works

Although Mozart wrote in a letter to his father dated October 17, 1777 that the organ was his passion and admitted that "In my eyes and ears the organ is the king of all instruments", he composed only a few organ works.

- Two small fugues in G major and D major, KV 154a, probably composed in 1772/1773

- Fugue in G minor, KV 401, probably composed in 1773, ends as a fragment after 95 bars

- Piece for an organ work in a clock (Adagio and Allegro in F minor for an organ work), KV 594, composed in 1790

- Allegro and Andante (Fantasy in F minor) for an organ cylinder, KV 608, composed in 1791

- Andante in F major for organ cylinder, KV 616, composed in 1791

Songs

- To Joy, Johann Peter Uz , KV 53 (KV 43b)

- The generous serenity *, Johann Christian Günther , KV 149 (KV 125d), * comp. by Leopold Mozart

- Secret love *, Johann Christian Günther, KV 150 (KV 125e), * comp. by Leopold Mozart

- Satisfaction in the low rank *, Friedrich Rudolph Ludwig von Canitz , KV 151 (KV 125f), * comp. by Leopold Mozart

- How unhappy I am not, KV 147 (KV 125g)

- Song of praise for the solemn St. John's Lodge, Ludwig Friedrich Lenz, KV 148 (KV 125h)

- Ah! spiegarti, oh Dio, KV 178 (125i / 417e)

- Ridente la calma, KV 152 (KV 210a)

- Oiseaux, si tous les ans, Antoine Ferrand , KV 307 (KV 284d)

- Dans un bois solitaire, Antoine Houdar de la Motte , KV 308 (KV 295b)

- Two German hymns, a) O Gotteslamm, b) As from Egypt, KV 343 (336c)

- To modesty, Johann Andreas Schachtner, KV 336b

- We owe it to the splendor of the great, Johann Timotheus Hermes , KV 392 (KV 340a)

- Be you my consolation, Johann Timotheus Hermes, KV 391 (KV 340b)

- I would be on my path, Johann Timotheus Hermes, KV 390 (KV 340c)

- Satisfaction, Johann Martin Miller , KV 349 (KV 367a)

- Come on, dear zither, come on, KV 351 (KV 367b)

- Gibraltar, Johann Nepomuk Cosmas Michael Denis , KV 386d

- Warning, KV 416c

- Song for journeyman journey, Joseph Franz von Ratschky , KV 468

- The magician, Christian Felix Weisse , KV 472

- Satisfaction, Christian Felix Weisse, KV 473

- The world betrayed, Christian Felix Weisse, KV 474

- The violet , Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , KV 476

- At the opening of the lodge assembly, Augustin Veith Edler von Schittlersberg, KV 483

- At the end of the lodge assembly, Augustin Veith Edler von Schittlersberg, KV 484

- Song of Freedom, Aloys Blumauer , KV 506

- The old woman, Friedrich von Hagedorn , KV 517

- The silence, Christian Felix Weisse, KV 518

- The song of separation, Klamer Eberhard Karl Schmidt, KV 519

- When Luise burned the letters of her unfaithful lover, Gabriele von Baumberg , KV 520

- Evening sensation to Laura, KV 523

- To Chloe, Johann Georg Jacobi , KV 524

- Little Friedrich's birthday, Johann Eberhard Friedrich Schall, final stanza Joachim Heinrich Campe , KV 529

- The dream image, Ludwig Hölty , KV 530

- The Little Spinner, KV 531

- My wishes, Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim , KV 539

- Song when moving out into the field, KV 552

- Longing for Spring , Christian Adolph Overbeck , KV 596

- Spring, Christian Christoph Sturm, KV 597

- The children's game, Christian Adolph Overbeck, KV 598

- Cantata: You of the immeasurable universe, Franz Heinrich Ziegenhagen , KV 619

A total of 42 works.

Canons

Mozart wrote textual and untextured canons. Among the texted works are works with ecclesiastical content:

- Kyrie (1770; KV 89)

- Alleluia (1788; KV 553) - the initial motif comes from the Alleluia intonation of the Holy Saturday liturgy

- Ave Maria (1788; KV 554)

But there are also canons with sometimes quite crude content, which are reminiscent of Mozart's Bäsle letters , which he wrote to his cousin Maria Anna Thekla Mozart . In many song books, the original text has been replaced by a new, "defused" one. For example:

- Kiss my ass (1782; KV 382c)

- Lick my ass fine, pretty clean (KV 382d; attributed to Mozart, composition by Wenzel Trnka )

- Bona nox! bist arechta Ox (1788; KV 561)

- Oh, du eselhafter Martin / Oh, du eselhafter Peierl (1788; KV 560b / 560a) - the two text versions of this canon refer to Mozart's drinking and bowling friends Philip ("Liperl") Jacob Martin and Johann Nepomuk Peierl, with whom he likes played rough jokes.

The four-part canon KV Anh. 191 (1788; 562c) is set for two violins, viola and bass.

Recordings

- Paul Badura-Skoda . Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. "Works for piano". Anton Walter hammer piano

- András ship . Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. "Piano works". Mozart's piano, Salzburg

- Linda Nicholson. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. "Sonatas for Fortepiano". Anton Walter, fortepiano

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt , Rudolf Buchbinder . Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. "Piano Concerti Nos. 23 & 25". Hammerklavier after Walter by Paul McNulty

- Viviana Sofronitsky . Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. 11CD box. "The first world complete works for piano and orchestra performed on original instruments". Orchestra: Musicae Antiquae Collegium Varsoviense "Pro Musica Camerata". Hammerklavier after Walter by Paul McNulty

reception

literature

Stage works

- Alexander Sergejewitsch Pushkin : Mozart and Salieri. Drama, 1832. Russian-German edition: translation and epilogue by Kay Borowsky . Timeline by Gudrun Ziegler, Reclam Universal Library No. 8094, ISBN 3-15-008094-0 .

- Albert Lortzing : Scenes from Mozart's Life . Singspiel in one act, Münster 1832

- Nikolai Rimski-Korsakow : Mozart and Salieri . Opera (based on the Pushkin text), 1897

- Peter Shaffer : Amadeus . Schauspiel, 1979, English edition: Amadeus, a Play. Edited by Rainer Lengeler (foreign language texts), Reclam Universal Library No. 9219, ISBN 3-15-009219-1 (Mozart from the perspective of the senile Salieri)

- Michael Kunze , Sylvester Levay : Mozart! Musical (world premiere on October 2, 1999 in the Theater an der Wien). Libretto by Michael Kunze, published by Edition Butterfly. Further performances in Hamburg, Budapest, Tokyo, Osaka, Karlstadt. CD Mozart! (Vienna No. 731454310727, Budapest No. 5999517155257)

- Moritz Eggert : From the tender pole . A collage from the music of Mozart for orchestra and singers, in which all characters from all existing Mozart operas appear. First performed at the opening concert of the Salzburg Festival in 2006.

- Ad de Bont , Kurt Schwertsik : Mozart in Moscow . Opera, 2014

Fiction

The character of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was used in many novels and stories, including in

- Hermann Hesse : The Steppenwolf. Frankfurt 1974, ISBN 3-518-36675-0 (Mozart as the representative of the "immortals" explains to the protagonist in an epistemological lecture about the eternal difference between ideal and reality.)

- Rotraut Hinderks-Kutscher : Donnerblitzbub Wolfgang Amadeus. Stuttgart 1955, ISBN 3-423-07028-5 (children's and young people's book.)

- Rotraut Hinderks-Kutscher: Immortal Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The years in Vienna, Franckh'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung © 1959.

- ETA Hoffmann : Don Juan in fantasy pieces in Callot's manner. 1814 (A traveling enthusiast (ETA Hoffmann?) Is visited by Donna Anna in the box during a Don Juan performance and mistaken for WA Mozart.)

- Jörg G. Kastner: Mozart magic . Munich 2001, ISBN 3-471-79456-5 (plays mainly during Mozart's last months until shortly after his death)

- Eduard Mörike : Mozart on the trip to Prague. Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-458-34827-1 (On the trip to the world premiere of Don Giovanni in Prague, Mozart found himself in the castle of Count von Schinzberg. His niece Eugenie in particular sensed Mozart's genius, but also the inevitability of his imminent death and that he will consume himself "quickly and inexorably in his own embers".)

- Wolf Wondratschek : Mozart's hairdresser. DTV TB 2004, ISBN 3-423-13186-1 (No one leaves Mozart's hairdresser unchanged.)

- Eva Baronsky : Mr. Mozart is waking up. Construction Verlag 2006, ISBN 3-351-03272-2 (The fictional story is told of how Mozart would have fared if he had woken up in 2006 in Vienna after his death in 1791.)

Works of art

- In 2006, Adi Holzer dedicated his artist portfolio to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the Mozart Suite . Regarding the screen print Mozart Engel contained therein , he writes: “The Mozart angel stands for everything that this god-blessed composer has created, for the whole power of his music, especially for his sacred works. A modest but deeply felt 'Thank you Mozart!' "

Movies

- 1939: Eine kleine Nachtmusik - directed by Leopold Hainisch ( entry on IMDB )

- 1942: Who the Gods Love - Director: Karl Hartl ( entry on IMDB )

- 1955: Mozart - Give me your hand, my life - Director: Karl Hartl . With Oskar Werner and Johanna Matz . ( Entry on IMDB )

- 1982: Mozart - multi-part biographical television film (F, I, B, Can, CH). Director: Marcel Bluwal . With Christoph Bantzer . ( Entry on IMDB )

- 1984: Amadeus - Director: Miloš Forman . With Tom Hulce and F. Murray Abraham . ( Entry on IMDB )

- 1984: The Three of Us - Director: Pupi Avati

- 1985: Forget Mozart - Director: Miroslav Luther. With Max Tidof , Katja Flint , Armin Mueller-Stahl , Uwe Ochsenknecht , Kurt Weinzierl . ( Entry on film.at )

- 2005: The Calf Knife - Director: Kurt Palm ( entry on IMDB )

- 2006: Mozart in Mannheim - TV documentary by Harold Woetzel ( ard.de )

- 2006: Mozartkugeln - director: Larry Weinstein ( entry on IMDB , homepage )

- 2006: Mozart - I would have done honor Munich in the Internet Movie Database (English)

literature

Catalog raisonnés

Biographical sources

- Ludwig Nohl (ed.): Mozart according to the descriptions of his contemporaries . Leipzig 1880

- Albert Leitzmann (ed.): Mozart's personality. Judgments of contemporaries . Leipzig 1914

- Arthur Schurig (Ed.): Leopold Mozart. Travel records 1763–1771. Dresden 1920

- Arthur Schurig (Ed.): Konstanze Mozart. Letters, records, documents. Dresden 1922.

- Otto Erich Deutsch (Ed.): Mozart. The documents of his life . 2nd Edition. Kassel 1961

- Wilhelm A. Bauer, Otto Erich Deutsch (Ed.): Letters and records. Complete edition . 7 volumes. Kassel et al. 1962 ff.

- Juliane Vogel (Ed.): The Bäsle letters . Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-15-008925-5 .

- Ulrich Konrad (ed.): Letters and notes. Complete edition . Extended edition with an introduction and additions. 8 volumes. Bärenreiter, Kassel and others and dtv, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-423-59076-9 .

- Stefan Kunze (Ed.): Letters . Reclam, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-15-010574-9 .

- Silke Leopold (Ed.): Good morning, dear woman! Mozart's letters to Constanze . Bärenreiter, Kassel and others 2005, ISBN 3-7618-1814-9 .

- Paul Ridder : The Myth of Mozart. A previously unknown portrait in his gallery. In: The Tonkunst. Vol. 5 (2011), pp. 63-65.

- Klaus Martin Kopitz : “You knew Mozart?” Unknown and forgotten memories of Beethoven , Haydn, Hummel and other contemporaries of Mozart. In: Mozart Studies. Volume 20 (2011), ISSN 0942-5217 , ISBN 978-3-86296-025-5 , pp. 269-309.

Biographies and overall interpretations

- Monika Reger: Mozart, family. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 3, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-7001-3045-7 .

- Franz Xaver Niemetschek : Life of the KK Kapellmeister Wolfgang Gottlieb Mozart. Retrieved on August 19, 2009 (first printing: Prague 1798). ; online at Project Gutenberg , 2nd edition. from 1808 - new edition: Franz Xaver Niemetschek, I knew Mozart. Ed. And come. v. Jost Perfahl, Langen / Müller 2005, ISBN 3-7844-3017-1

- Georg Nikolaus von Nissen : biography of WA Mozart. Based on original letters and collections of everything written about him; with many new supplements, stone impressions, music sheets and a facsimile. Leipzig 1828, ISBN 3-487-04548-6 . Reprinted and annotated by Rudolph Angermüller . Olms, Hildesheim / Zurich and others 2010, ISBN 978-3-487-08493-0 . (Reprint of the 1828 edition)

- Otto Jahn : WA Mozart. 4 volumes. Leipzig 1856 ff .; Reprint Directmedia Publishing , Berlin 2007, and Kleine Digitale Bibliothek , Volume 40, CD-ROM, ISBN 978-3-89853-340-9 .

- Ludwig Meinardus: Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1885, pp. 422-436.

- Arthur Schurig , Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, his life and work due to the mainly by Nikolaus von Nissen. biogr. Sources and results d. latest research. 2 volumes. Leipzig 1913

- Rudolph Angermüller : Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, life and work: biographies, letters and contemporary documents on 36,000 pages; with current Köchel directory . DVD-ROM, Directmedia Publishing , Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-86640-708-4 .

- Eva Gesine Baur : Mozart. Genius and Eros. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66132-7 .

- Axel Brüggemann : Who was Mozart? Jacoby & Stuart, Berlin 2009, only consecrated on December 7th and ISBN 978-3-941087-52-1 .

- Alfred Einstein : Mozart, his character, his work. (1945). German version (original edition): Mozart - His character, his work (1947). New edition Fischer TB, 2005, ISBN 3-596-17058-3

- Norbert Elias : Mozart. On the sociology of a genius. Edited from the estate by Michael Schröter. Suhrkamp TB, 1993, ISBN 3-518-38698-0 .

- Sabine Henze-Döhring: Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-428-00199-0 , pp. 240-246 ( digitized version ).

- Peter Gay : Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Claassen Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-546-00227-X .

- Martin Geck : Mozart. A biography. Rowohlt, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-498-02492-2 .

- Brigitte Hamann : Mozart. His life and his time. Ueberreuter, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-8000-7132-0 .

- Wolfgang Hildesheimer : Mozart . New edition Insel TB, 2005, ISBN 3-458-34826-3

- Thomas Hochradner, Günther Massenkeil: Mozart's church music, songs and choral music. The manual. Laaber-Verlag 2006, ISBN 3-89007-464-2 .

- Heinrich Eduard Jacob : Mozart. Spirit, Music and Destiny. Scheffler Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1956. Latest new editions: Heyne Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-453-13884-8 . Also Heyne Verlag, Munich 2005, under the title Mozart. The genius of music. ISBN 3-453-60028-2 .

- Ulrich Konrad : Wolfgang Amadé Mozart. Life · Music · Works. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2005, 3rd edition 2006, ISBN 9783761818213 .

- Malte Korff: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-518-18210-2 .

- Konrad Küster : Mozart. A musical biography. 1990.

- Silke Leopold (Ed.): Mozart Handbook. Metzler / Bärenreiter, Stuttgart / Kassel 2005, ISBN 3-476-02077-0 .

- Piero Melograni: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. A biography. Siedler, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-88680-833-5 .

- Clemens Prokop : Mozart, the player. Story of a quick life. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2005, ISBN 3-7618-1816-5 .

- Maynard Solomon : Mozart. One life. Metzler, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-476-02084-3 .

- Franz Daxecker : The Innviertel family of surgeons Mozart - a genealogical search for clues. In: Upper Austrian homeland sheets. No. 65, Linz 2011, pp. 53–62, land-oberoesterreich.gv.at [PDF]

- Manfred Hermann Schmid (ed.): Mozart studies . Schneider, Tutzing 1992–2013 (volume 1–22), Hollitzer, Vienna 2015 ff. (Volume 23 ff.), ISSN 0942-5217.

- Claude Tappolet: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . October 9, 2007 .

Monographs

- Volkmar Braunbehrens : Mozart in Vienna. Piper, Munich / Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-492-24605-2 .

- Fritz Hennenberg: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Rowohlt, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-499-50683-1 .

- Hans-Josef Irmen : Mozart as a member of secret societies. Prisca, Zülpich 1991, ISBN 3-927675-11-3 .

- Ulrich Konrad : Wolfgang Amadé Mozart. Life, music, works. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2005, ISBN 3-7618-1821-1 .

- Werner Ogris : Mozart in family and inheritance law of his time. Engagement, marriage, inheritance. Böhlau, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-205-99161-3 .

- Harald Strebel : The Freemason Wolfgang Amadé Mozart. Stäfa 1991, ISBN 3-907960-45-9 .

- Guy Wagner: Brother Mozart - Freemasonry in Vienna in the 18th century. Amalthea, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-85002-502-0 .

- Manfred Wagner : Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Work and life. Steinbauer, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-902494-09-3 .

- Christoph Wolff : At the gate of my happiness. Mozart in the service of the emperor (1788–1791). translated by Matthias Müller. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2013, ISBN 978-3-7618-2277-7 .

- Martin Kluger : WA Mozart and Augsburg. Ancestors, hometown and first love. context Medien und Verlag, Augsburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-939645-05-4 .

- Laurenz Lütteken: Mozart: Life and Music in the Age of Enlightenment , Munich: CH Beck, [2017], ISBN 978-3-406-71171-8

Audio books