Illuminati Order

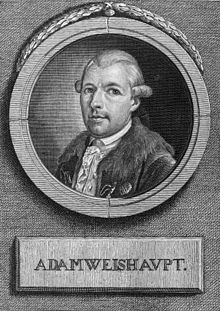

The order of the Illuminati ( Latin illuminati , the enlightened ones ) was a short-lived secret society with the aim of making the rule of people over people superfluous through enlightenment and moral improvement . The order was founded on May 1, 1776 by the philosopher and canon lawyer Adam Weishaupt in Ingolstadt and existed primarily in the Electorate of Bavaria until it was banned in 1784/85 .

Numerous myths and conspiracy theories have grown up around the alleged survival of this society and its alleged secret activities, including the French Revolution , the struggle against the Catholic Church and the pursuit of world domination .

history

founding

The professor of canon law and practical philosophy at the University of Ingolstadt , Adam Weishaupt (1748–1830), founded the League of Perfectibilists (from Latin perfectibilis : able to perfect) with two of his students on May 1, 1776 . Weishaupt chose the owl of Minerva , the Roman goddess of wisdom, as the symbol of the covenant . The background to this was the intellectual climate at the university, which was almost completely dominated by former Jesuits , whose order had been abolished in 1773 . The only twenty-eight year old Weishaupt was the only professor in Ingolstadt without a Jesuit past and accordingly isolated in the teaching body, which was also due to his enthusiasm for the ideas of the Enlightenment and his sometimes conflict-prone demeanor. In order to offer his students protection from Jesuit intrigues, which he suspected everywhere, but above all to give them access to contemporary literature critical of the Church, he founded with five of them a "Secret Wisdom Association" on May 1, 1776, which he shared with ancient Myths, especially from the context of the Mysteries of Eleusis , garnished. According to the British historian Peggy Stubley, Weishaupt's establishment at that time resembled “more of an extra-curricular student study group [...] than a dissident cell on a conspiratorial course ”.

In addition, Weishaupt saw in the Order of the Gold and Rosicrucians , a mystical , spiritual , anti-Enlightenment order in Freemasonry , a growing evil that had to be fought. He reported on this founding occasion of the Illuminati in 1790 in his work Pythagoras or Reflections on the Secret Art of the World and Government :

“But two circumstances were decisive. At the same time [1776] an officer by the name of Ecker had set up a lodge in Burghausen , which went on alchemy and began to spread enormously. A member of this lodge came to Ingolstadt to advertise there and to recruit the most capable among the students. Unfortunately, his selection fell on those on whom I had also cast my eye. The thought of having lost such hopeful youths in this way, and also of being infected with the pernicious plague, with the penchant for gold-making and similar follies, was tormenting and unbearable for me. I discussed this with a young man in whom I had the most confidence. He encouraged me to use my influence on the students and to control this mischief as much as possible through an effective antidote, by establishing a society [...] "

In 1777 two Munich Masonic lodges were infiltrated , one of which Weishaupt was also accepted into. The order took a further, albeit modest, upswing in the following year, when it was reorganized by Franz Xaver von Zwackh , a former student of Weishaupt and later governor of the Palatinate . Weishaupt proposed the "Order of the Bees" as the new name because he had in mind that the members should collect the nectar of wisdom under the guidance of a queen bee. But the decision was made for the “Bund der Illuminati” and finally for the “Illuminati Order”. In 1780 this had about 60 members.

The first few years were rather chaotic, as Weishaupt was not willing to do the organizational and content-related work alone. On the other hand, he neither wanted nor could he delegate. Like his closest colleagues Zwackh and Franz Anton von Massenhausen, he often felt overwhelmed or misunderstood. Finally, a so-called Areopagus was appointed to lead the order in Munich , but it was also not free of conflict. Several months of gaps in the sources in 1777 and 1779 allow the conclusion that the order did not work at all during this period due to the dispute.

Short flowering

Another reorganization took place after the entry of the Lower Saxon nobleman Adolph Freiherr Knigge . He had been recruited for the order on July 1, 1780 in the L'Union Lodge in Frankfurt am Main by the Bavarian court chamber councilor Constantin Costanzo, and after his accession he developed a lively activity. In 1782 he gave the order, which, according to Weishaupt's own admission, “actually didn't exist at all, just in his head”, a structure similar to that of Masonic lodges: the high grades that the adepts could attain after having passed through the traditional three degrees of Freemasonry , were now formed by the Illuminati Order. In this way, as Knigge wrote in letters to Weishaupt in 1780 and 1781, "in a certain way the whole of Freemasonry can be governed" and in a new form "combined with the operational plan of the O [rdens] for the best and enlightenment of the world" . Knigge developed a narrative for this , which he informed Weishaupt by letter on July 13, 1781: According to this, there has always been a small society of men "who opposed corruption and the priest's arts" and the oldest sources of religion and Philosophy to purify this. They are the real authors of the Enlightenment. They initiated the Freemason "Spartacus" into their wisdom, who then founded the Society of the Illuminati. This idea of being able to join a centuries-old association that was more assertive than any other secret society turned out to be enormously effective in advertising.

With this strategy Knigge dissuaded the Illuminati from Weishaupt's original plan of the "secret wisdom school". Now students were no longer recruited, who had to be trained and shaped by reading regulations, but seasoned men who had already made careers in the state and society. With that he had great success. The background to this was the crisis that German Freemasonry had got into at its highest level after 1776 with the collapse of the Strict Observance . With this rather apolitical-romanticizing movement, which claimed to be in the footsteps of the Knights Templar , which was repealed in 1312, Karl Gotthelf von Hund and Altengrotkau succeeded in recruiting the German lodges under his leadership. For years he had claimed that he was in contact with "unknown superiors" who had let him in on the deepest secret of Freemasonry. When, after von Hund's death in 1776, no “secret superiors” reported, there was great perplexity in the boxes. Knigge recognized the opportunity that this offered the Order of Illuminati. On December 16, 1780 he wrote to Weishaupt:

"A revolution is imminent for bricklaying [...] [...] So it is necessary not to lose the helm so that other clever minds do not precede us."

Shortly afterwards he published an anonymous conspiracy scenario under the title Ueber Jesuiten, Freemaurer und Deutschen Rosenkreuzer on Weishaupt's order , in which he claimed that the Jesuit order was actually behind the Strict Observance, which was fighting the Enlightenment, recatholizing Germany and making it the rule of the Pope want to submit. Therefore, a counter-conspiracy is necessary, which the Jesuits fight in mirror image with their own methods, but with an educational goal:

“If a society of the best of people met according to just as cautious a plan, and trained their pupils to be virtue, just as the Jesuits trained theirs to be wicked, if, instead of fanaticism, from their earliest youth they taught them with love for the human race, with lust to spread noble great principles and to be effective on a large scale for the good of the world fulfilled - what this society would not be able to achieve. "

This "society of the best people" should be the Illuminati order. At the great Freemasonry Convention of the Strict Observance , which took place from July 16 to September 1, 1782 in Wilhelmsbad , the Illuminatist Franz Dietrich von Ditfurth was able to win opinion leadership for the order, even though he arrived a week late and followed etiquette himself had not succeeded in having his Masonic lodge set himself up as a delegate and therefore could not participate. The Templar system was abandoned; the Order of the Gold and Rosicrucians, which in turn had endeavored to inherit the Strict Observance, remained in the minority. The Illuminati were able to win over numerous prominent Freemasons, including Johann Christoph Bode , one of the leading representatives of the Strict Observance. Knigge would have liked to incorporate the entire organization of the Strict Observance, but Weishaupt insisted that, according to the logic of the order, only individuals could be accepted.

The order was in some cases very successful in infiltrating the absolutist state: the Bavarian censorship board, for example, consisted mainly of Illuminati, including Zwackh, Maximilian von Montgelas , Karl von Eckartshausen and Aloys Friedrich Wilhelm von Hillesheim , until the Elector's intervention in 1784 . The censors who did not belong to the order also sympathized with the Enlightenment, and the practice of the authority was accordingly: Writings by ex-Jesuits and other counter-Enlightenment or clerical writings, even prayer books, were banned, while Enlightenment literature was promoted. The Illuminati were also able to temporarily gain influence over the Reich Chamber of Commerce. In total, branches of the order, so-called Minervalkirchen, or active individual members can be identified at 90 locations, both within the Holy Roman Empire and outside of it: there were branches in the Netherlands , Hungary and Transylvania . The order was particularly active in Munich, where there were two, and in Vienna, where there were four branches of the order.

Crisis and ban

The rapidly increasing number of members also meant the beginning of the end of the Illuminati Order, because conflicts within the order broke out: Weishaupt criticized that too many members were accepted too quickly without any examination of whether they were suitable for the objectives of the order. He also found the theosophical - esoteric images and motifs appalling, which Knigge wanted to use in connection with contemporary high degree freemasonry in the elaboration of the individual degrees. Thereupon he worked out texts for the degree Illuminatus dirigens in competition with Knigge , which caused considerable confusion for the cathedral provost of Eichstätt Ludwig Graf Cobenzl , also a leading member of the order. Knigge unceremoniously placed Weishaupt's design a little higher in the illuminatic hierarchy and distributed his own design in the order, which led to a complaint from the Göttingen philosophy professor Johann Georg Heinrich Feder to Weishaupt that this text was insufficiently informative. In contrast, Knigge's designs went too far for the Eichstätt members of the Areopagus. They feared the censorship and changed it on their own responsibility. Weishaupt then asked Knigge to withdraw texts that he had already agreed to. There were also differences of opinion between Ditfurth and Knigge about the future content and strategies of the order.

Knigge was deeply dissatisfied that the statutes, degrees and teachings of the order were still inadequately worked out and saw his achievements in recruiting new members not honored. He teamed up with Bode and tried to take over the leadership of the order. He also continued to pursue his plan to merge the order with the remnants of the Strict Observance that still existed, which Weishaupt strictly rejected. In a letter, Knigge even threatened to divulge religious secrets to Jesuits and Rosicrucians, which only increased Weishaupt's suspicion: it was causing considerable concern that Bode and Knigge represented representatives of the absolutist authorities such as the Princes Karl of Hesse and Ferdinand of Braunschweig as well as the Dukes Ernst von Saxe-Gotha and Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar had brought into the order. Ernst II used the Gotha Illuminati Lodge as a secret shadow cabinet.

As a result, the dissent between Weishaupt and Knigge came to a head to such an extent that the medal threatened to break. In February 1784, an arbitration tribunal called “Congress” was convened in Weimar, in which Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , Johann Gottfried Herder and Duke Ernst von Sachsen-Gotha were involved. Surprisingly for Knigge, the Congress ruled that a completely new Areopagus had to be formed; both leading figures of the order should give up their positions of power. This seemed like a workable compromise. But since it was foreseeable that the founder of the order would remain influential even without a formal chairmanship in Areopagus, it meant a clear defeat for Knigge. It was agreed not to disclose and to return all papers. Knigge left the Order of Illuminati on July 1, 1784. He then turned away from the "fashion folly" of wanting to improve the world through secret societies. Weishaupt handed over the leadership of the order to Johann Martin Graf zu Stolberg-Roßla.

In the midst of the internal quarrels, the Illuminati came into the focus of the Bavarian authorities. She was suspicious of the aims of enlightened secret orders, as they aimed to change the traditional order, even to establish a “rational state” by infiltrating public offices. After an unsuccessful application for admission, the Munich publisher Johann Baptist Strobl published two anti-illuminatic polemics by Joseph Marius Babo , which resulted in a long “press battle” over the order. On top of that, the order had dared to interfere in high politics. He advocated the elector Karl Theodor's project , which was highly controversial among the princes of the empire , to exchange his Bavarian territories for the Austrian Netherlands . Members of the order had tried to persuade the young Hofkammerrat Joseph von Utzschneider , a former Illuminati, to search the papers of Maria Anna , the widow of Karl Theodor's predecessor , in order to hand over their contents to Emperor Joseph II . Utzschneider then not only uncovered the plan, but also a list of members of the order. Maria Anna warned Karl Theodor about the plans of the order, but initially he remained inactive. Only when the court archivist Karl von Eckartshausen , also a former member of the order, reported the theft of documents from the electoral archives, did he issue a decree on June 22nd, 1784 that forbade all “communities, societies and associations” that without his “sovereign confirmation “Were founded. The Illuminati were meant, even if they were not explicitly named in the text.

Since the Illuminati continued to collect monetary contributions and hold lodge meetings, another edict followed on March 2, 1785, under pressure from Ignaz Frank, the elector's confessor , which this time called the Illuminati and Freemasons by name and banned it as treason and anti-religion. During house searches, various papers of the order were confiscated, which provided further evidence of its radical goals. Papers found on a deceased courier revealed the names of some members. In the same year, Pope Pius VI also declared . in two letters (from June 18 and November 12) to the Bishop of Freising the membership in the order as incompatible with the Catholic faith.

The persecutions of the members of the order following the prohibitions of 1784/85 were kept within limits. There were house searches and confiscations; some councilors and officers lost their jobs, some members of the order were expelled from the country, but none was imprisoned. The public initially perceived the persecution as the work of the Jesuits, with particular suspicion of Ignaz Frank, a former religious and Rosicrucian. Weishaupt himself, who was not even known to be the founder of the order, was charged with recommending the acquisition of the Dictionnaire historique et critique by Pierre Bayle . The elector ordered him to publicly profess his Catholic faith in front of the Senate of Ingolstadt University. Weishaupt escaped this by fleeing, first to the Free Imperial City of Regensburg , then in 1787 to Gotha , where Duke Ernst procured him a sinecure as a councilor. An important collection of sources on the history of the order, the so-called Sweden box , which has been available for research since 1990 , also comes from the possession of this illuminatic prince .

Already in April 1785 Stolberg-Roßla had officially suspended the order in southern Germany and Austria, that is, declared it temporarily canceled. The Minerval Church of Stagira in Bonn also dissolved. On 16 August 1787 was followed by a third, yet sharper ban edict to recruit members for Freemasons and Illuminati under death penalty presented, from which one can conclude that it was believed in circles of authority to a continuation of the Illuminati. Members of the order in the Bavarian civil service who had been caught had to make a comprehensive confession and revoke their membership if they did not want to be dismissed. The result were confessional writings like that of Zwackh. These texts, some of which were also published, were heavily embellished and therefore have little source value. The original papers of the order that were seized during the house searches were also published in March 1787 on the instructions of the Bavarian government and were part of a flood of publications about the order, some of which were sensational. As early as 1786, the Saxon-Weimar-Eisenach Chamberlain, Ernst August Anton von Göchhausen, had his revelation of the system of the cosmopolitan republic in print, in which he linked the spreading Illuminati hysteria with the older suspicions of the enlighteners against the " despotism " of the Jesuits: Behind all this lies “the great secret laboratory in which the various Roman Jesuit cosmopolitan magic potions were and are still being prepared”.

A second, much more violent wave of this Illuminati hysteria began after the French Revolution , when the fear of the Jacobins merged with the older fear of the Illuminati into a single fearful fantasy. In this mood, the Bavarian State Minister Montgelas - although a former Illuminate himself - had all secret societies banned when he took office in 1799 and again in 1804. How much the German public was fascinated by mysterious and uncanny secret and initiation societies in the years around the French Revolution can be seen in various literary works of the time, from Schiller's Der Geisterseher (1787/89) to Jean Paul's The Invisible Lodge (1793 ) to Goethe's Der Groß-Cophta (1792) and the mysterious tower society in Wilhelm Meister's apprenticeship years (1796).

From Gotha, Bode tried to keep the union alive after 1787 and set up successor organizations with the Weimar Minervalkirche, the “Order of Invisible Friends” or the “Association of German Freemasons”. The order also expanded to Italy, Russia and France. In the sharply anti-illuminatic climate of the revolutionary years, Bode had to stop these efforts in 1790. His death in 1793 is considered to be the end of the order's activities. An attempt to organize by former Illuminati called The Moral Covenant and the Consent was unsuccessful. Today in Ingolstadt only a plaque on the building in which the assembly hall of the Illuminati was located reminds of the order. The building is located at Theresienstraße 23 (previously Am Weinmarkt 298) in what is now the city's pedestrian zone.

structure

aims

The Order of the Illuminati was completely committed to the Enlightenment worldview. The aim was to improve and perfect the world and its members (hence the old name perfectibilist ). In this way the Illuminati wanted to achieve the freedom they understood politically. Their ideas are considered the first step in the politicization of the Enlightenment. The Illuminati were "the first known political secret society of modern times".

In 1782, Weishaupt justified the goals of the order in his speech to the new Illuminatos dirigentes with its own philosophy of history : According to this, the universe is "the effect of a supreme, most perfect and infinite cause" and thus harmonious and good. Man is originally good too. Using historical thinkers like Joachim von Fiore , he postulated three world ages : In the “childhood of mankind” there was neither rule nor property nor the pursuit of power. This only found its way into the "youth" when the first states emerged. These would have served to satisfy the growing needs of people, which Weishaupt considered to be the engine of world history: "The history of the human race is the history of his needs, how one emerged from the other". The originally useful states have slipped more and more into "despotism". But this itself creates a new need, namely the longing for freedom: "Despotism itself should be the means to [...] facilitate the path to freedom", Weishaupt wrote in an elaboration for the mystery class of his order. In the maturity of the human race it will then be overcome non-violently through enlightenment and through the self-control it teaches.

"So whoever wants to introduce general freedom, spread general enlightenment: but enlightenment does not mean knowledge of words but of factual knowledge, is not knowledge of abstract, speculative, theoretical knowledge that inflates the mind but does nothing to improve the heart."

For Weishaupt, enlightenment was above all education , and not just the often only external transfer of knowledge, but primarily the education of the heart, morality . It had a moral quality in the first place . Spreading enlightenment and “bringing mankind back to the 'Promised Land'” is the task of secret societies, “secret schools of wisdom”, for which he claimed an ideal line of tradition from early Christianity to Freemasonry . The Masonic lodges of his presence have become apolitical, but they serve as a mask for the Illuminati. With their help, the Illuminati utopia could be realized, which at the same time represents a return to the original state:

“Every householder will one day, like Abraham and the patriarchs before , the priest and the absolute master of his family and reason will be the only code of law for men. This is one of our great secrets. "

At the inauguration of the philosophers degree Order members should then find out that in the course of further development, the inequality should be repealed between people, which was the cause of all discord and all tyranny: To become the "so long derided novel from the golden age , brought this age-old favorite idea of the human race to reality ”.

Medieval chiliasm and modern utopia, premodern prophecy of a redeemed world and modern prognosis of how this can be achieved through one's own actions are mixed in this historical picture . Weishaupt linked two opposing messages with one another: On the one hand, he preached a quietism that relieved the members of the order of any responsibility for the progress of history; on the other hand, he called for a subversive activism that should actively undermine the existing system of rule. Which of the two aspects was the more important, he left in the balance. On the one hand, it was said that there was nothing to do but wait, because the time of absolutist despotism would come to an end by itself based on internal logic. On the other hand, Weishaupt claimed that the Illuminati would contribute to the lifting of the despotism solely through their activity, indeed through their very presence.

The abolition of absolutist rule should not take place by way of a revolution , but with the means of personnel policy : one wanted to take on more and more key positions in the absolutist state in a "long march through the institutions " in order to gradually bring it into its own power. Because Weishaupt no longer gave any information about the last stages of his utopia, it is now a matter of dispute whether the Illuminati wanted to abolish or take over the state after it had infiltrated it. A democracy in the sense of popular sovereignty was, unlike in the case of the Jacobins , with whom later critics equated them, at least not their goal. According to Hans-Ulrich Wehler , the order aimed at a moderately authoritarian regiment of an enlightened elite : According to this, the Illuminati themselves were part of the enlightened reform absolutism that they were preparing to overcome. The French Germanist Pierre-André Bois believes that the Illuminati “didn't want to destroy the state, but rather reform it from within . Their struggle was not directed against power, but against its forms ”. The Austrian historian Helmut Reinalter, on the other hand, believes that they were striving for “a cosmopolitan world order without states, princes and estates ”. The German historian Monika Neugebauer-Wölk speaks of an “ anarchist variant” of the Enlightenment utopia for progress that was received in the Order of Illuminati.

organization

The Illuminati were one of numerous societies and associations that were characteristic of the development of the modern phenomenon of the public during the Age of Enlightenment, as described by Jürgen Habermas in his study Structural Change of the Public . While the pre-modern class society had reproduced itself socially either in the church or at the royal court, there was now the possibility of reading societies , various charitable associations (e.g. Hamburg's Patriotic Society ), Masonic and Rosicrucian lodges or even secret societies like the Illuminati To get together socially across class boundaries on an at least principally egalitarian level.

In contrast to the other forms of this new sociability, however, the Illuminati had an explicitly political program, whereas Freemasons, for example , do not want confessional, religious or party political disputes to this day. Freemasons also acknowledge their affiliation and are therefore, unlike the Illuminati, not a secret society in the true sense of the word. Although the Illuminati adopted Masonic structures such as the lodge and a degree system, they did not belong to Freemasonry. They did not work in the national Masonic organizations, the Grand Lodges or Grand Orientals.

In order to be able to infiltrate Freemasonry better, Knigge gave the Illuminati a structure based on Freemasonry with imaginatively titled degrees, each of which had its own initiation ritual and its own "secrets", which were revealed to the initiate: A "nursery school", during his reform of the order. should introduce the inexperienced into the lodge and secret society, consisted of the degrees novice, Minerval (derived from Minerva , the Roman goddess of wisdom) and Illuminatus minor (Latin for "lower enlightened"). The “mason class”, based on Freemasonry, contained the degrees of apprentice, journeyman, master, Illuminatus maior (Latin for “higher enlightened person”) and Illuminatus regens (Latin for “leading enlightened person”). The order was crowned by the “mystery class”, which consisted of the grades priest, regent, magus (lat. For “magician”) and rex (lat. For “ruler”). Of the members of the Order, 14% belonged to the first class, 45% to the second and 8% to the third class. It is no longer possible to say today of a third what grade they had achieved in the Order. For a time 19 members belonged to the Areopagus, the actual leadership of the order. According to Hermann Schüttler, the fact that 112 men had made it into the mystery class is an indication that “considerably more people were familiar with Weishaupt's plans than had previously been assumed”.

Admission to a higher degree was accompanied by all sorts of esoteric rituals, as they were common in high degree freemasonry and among the Rosicrucians: The initiate in the mystery class, for example, was led into a darkened room, was presented with symbolic objects and was presented by two priests in white robes with red velvet hats taught about the arcanum of this class. In contrast to the Rosicrucians, the content of this teaching was not religious, but educational, namely the philosophy of history presented above. The rules and rites for the upper class, however, were not fully worked out in the short time the Order existed. According to the historian Reinhard Markner, the illuminatic system of binding degree texts is “a fictional figure that owes itself to the revelatory publications of the period after 1786 and the understandable desire of historians for clarity”.

As effective advertising mystification of each member of the order received at his initiation also a secret name ( " nom de guerre " ), who was always non-Christian or at least non-Orthodox origin: Weishaupt called himself after the leader of the ancient slave rebellion Spartacus , Knigge was Philo , a Jewish philosopher, and Goethe was named Abaris after a Scythian magician . There were also secret names in geography (Munich was called Athens , Tyrol became the Peloponnese , Frankfurt was Edessa and Ingolstadt was Eleusis ); even the date was given according to a new secret calendar with Persian month names, the year counting began with the year 630, the date of the Zoroastrians' flight from the Muslims.

The religious names contributed to the equality among the Illuminati: Since they only knew each other by religious names in the first two degrees, they could not know of each other who was noble, who was a civil, who was a university professor, who was only a bar owner or a student. In addition, they were part of the rigid educational program that the Order imposed on its members. Each Illuminati not only had to deal mentally with his namesake , he also received a monthly reading from his superiors, in which enlightenment and deistic works with increasing degrees played an increasingly important role: According to Stubley, this shows that Weishaupt “always in his essence University professor ”remained. The compulsory reading canon included classics such as Seneca , Dante and Petrarca , contemporary fiction such as Christoph Martin Wieland and Alexander Pope , popular philosophical works such as those by Adam Smith , Christoph Meiners and Johann Bernhard Basedow , but also materialistic and atheistic works such as Paul Henri Thiry the Elder Holbach's Christianity Unveiled and the anonymous Traité des trois imposteurs - these books were banned everywhere in Germany.

The adept also had to record his intellectual and moral development in the form of a diary in so-called Quibuslicet notebooks (from Latin quibus licet - who is allowed [add: to read this]), which were archived. If they were badly managed or if they did not contain the planned progress, the superior of the order replied with a “Reprechen slip” ( French reproche “reproach”, “reproach”). In addition, the members of the order had to prepare written elaborations on subjects which the upper grades considered appropriate for their spiritual development. The exchange of all these notebooks, slips of paper and works and their evaluations took place in a network of knowledge acquisition that was determined and controlled by the upper levels of the order's hierarchy.

How pronounced this hierarchy in the order was also shown by the oath in which each initiate had to pledge "eternal silence in unbreakable loyalty and obedience to all superiors and the statutes of the order". The German historian Reinhart Koselleck also points out the esoteric structure of the order, which means that new members were deliberately deceived about its true goals. In the “nursery school” the novices were told that it was by no means the aim of the order “to undermine the secular or spiritual governments, to take control of the world and so on. If you imagined our society from this point of view, or if you stepped into it with this expectation, you have cheated yourself tremendously ”. That was untruthful, because in the highest degree of the order the “greatest of all secrets” was to be revealed, “which so much longed for, so often fruitlessly sought to lead [the] art of governing people to the good [...] and then to cite everything that people have hitherto dreamed of and only the most enlightened ones could ". The deepest arcanum of the Illuminati was thus their own moral system of rule, which was already practiced within the order, but should now also be applied externally.

This deception and harassment of the members in the lower grades soon aroused criticism within the order. They were owed to Weishaupt's “World Education Plan”, in which he sought to perfect the individual through education or encouragement for self- education and through hidden guidance. The prerequisite for such an improvement in the individual was on the one hand his obedience, which was to be achieved through personal example of the higher grades, through fear of the lower grades and through exploitation of the “human tendency towards the wonderful”. On the other hand, a total knowledge of all personal secrets of those to be educated was required. Weishaupt adopted this concept from his fiercest opponents, the Jesuits, with their cadaver obedience and their careful but all the more effective leadership through confession . An opponent of the order criticized this concept as "despotism of the Enlightenment". According to the historian Manfred Agethen, the Illuminati were connected to their opponents in a dialectical entanglement: In order to emancipate the individual from the spiritual and spiritual rule of the church, Jesuit methods of examination of conscience were used; In order to promote the triumphant advance of the Enlightenment and of reason, a system of high degrees and a mystical fuss was put in place, which reminded of the enthusiastic irrationalism of the Rosicrucians; and in order to finally free mankind from the despotism of princes and kings, the members were subjected to an almost totalitarian control and psychotechnics . According to the judgment of the historian Sieglinde Graf, the Illuminati are therefore not part of the democratic tradition in Germany. The Germanist Wolfgang Riedel considers the “subordination, yes, submission” to the “superiors”, the “renunciation of private insight” in the “faithful” trust in the better insight of the higher authorities ”to be a“ system of artificially maintained immaturity ”. Pierre-André Bois, on the other hand, sees the organization in small, independent cells and the at least ideally collective leadership through the Areopagus as entirely modern approaches.

Members

The Illuminati had some success: a total of 1,394 order members can be identified, around a third of whom were also Freemasons. The focus was on Bavaria and the small Thuringian states of Weimar and Gotha; outside of the Reich, Illuminati can only be found in Switzerland .

The historian Hermann Schüttler examined the social structure of the verifiable members of the order and came to the following result: 35% were nobles, 16% clergy , mostly members of the lower clergy or religious . 45% were considered scholars, i.e. in the broadest sense as academics or intellectuals . 9% of the Illuminati were in the military , the vast majority of them officers . A fifth ran a trade , 9% were students or interns , almost half were civil servants . Weishaupt himself proudly stated in 1787 that the order had succeeded in providing more than a tenth of the higher civil service in Bavaria.

Several prominent intellectuals were members of the order. In addition to Knigge and Herder, the Swiss pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and the German educationalist Rudolph Zacharias Becker were Illuminati. Goethe was also a member of the order, but his motives are controversial: After the American Germanist W. Daniel Wilson , Duke Carl August and he only joined to research the order. The Germanist Hans-Jürgen Schings doubts this, but calls Goethe's commitment to the order "modest" overall. He and his duke later used their membership to the detriment of the order, for example by preventing Weishaupt from being appointed to a professorship at the University of Jena . Christoph Martin Wieland had personal connections to Illuminati, but never became a member himself. That Weishaupt had placed three of his works on the Order's binding reading canon was embarrassing to him after its disclosure; he was long suspected of secret membership. The Egyptologist Jan Assmann points to the Viennese Masonic lodge Zur Wahren Eintracht , with which the Illuminatist Ignaz von Born created a center of cultural radiance. By forming the lodge into a research lodge, he followed Weishaupt's concept of the order as a "kind of learned academy ", where "every pupil had to be enrolled in a scientific field and devote his energies to it, [...] to collect and research". Carl Leonhard Reinhold, for example, came from Born's researcher lodge in Vienna and then came to Weimar in 1784, where he married into Wieland's family a year later. Even Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart took part in the meetings of the lodge, in the lists of members of the Order, however, he does not appear.

This temporary success of the Illuminati Order cannot hide the fact that it consisted for the most part of rather secondary academics, who perhaps flocked into the Order precisely because they hoped for career opportunities from it; a hope that correlated well with Weishaupt's plan of infiltration. These goals were of course unknown to newly admitted members. The order hardly achieved its real goal, namely to educate the intellectual and political elite of society, and it never posed a real threat to the Bavarian state. Apart from the exceptions mentioned (Goethe, Herder, Knigge), all the really important representatives of the German Late Enlightenment either stayed away from the order (Schiller, Kant , Lessing , but also Lavater , for whom Knigge had long tried in vain) or stepped like Friedrich Nicolai quickly out of disappointment with the rigid structures within the order.

reception

Myths and Conspiracy Theories

Many conspiracy theories continue to this day that the Illuminati continued to exist after they were banned and that they are a particularly powerful secret society that is behind a large number of phenomena that are viewed as negative. For example, they are said to have influenced the formation of the USA . This is untenable because of the chronological sequence (the American War of Independence began as early as 1775, i.e. before the order was founded).

The Illuminati were also held responsible for the French Revolution . The French priest Jacques François Lefranc first expressed this momentous suspicion in 1791 in his book Le voile levé pour les curieux ou les secrets de la Révolution révéles à l'aide de la franc-Maçonnerie (translated as: “The veil lifted for the curious, or the revealed secrets of the revolution through the aid of Freemasonry ”). The French former Jesuit Augustin Barruel and the Scottish scholar John Robison spread this thesis in their shortly thereafter written works on the causes of the French Revolution. Independently of one another, they tried to prove that it was not the spread of the ideals of the Enlightenment, the bad harvest of the previous year and the poor crisis management of King Louis XVI. started the revolution, it was the Illuminati. For this, they named three alleged evidence in particular:

- Almost all the major leaders of the revolutionaries were Freemasons. In this way, against historical facts, they equated Freemasons and Illuminati.

- Shortly before the revolution, there was a Masonic lodge in France, Les Illuminés ("the enlightened"). In fact, this group was very small, not very influential and represented a mystical trend, Martinism , which had nothing to do with the radical enlightenment of Knigges and Weishaupt.

- Johann Christoph Bode traveled to Paris in 1787 to trigger the revolution. In fact, the purpose of his stay, which only lasted from June 24th to August 17th, was completely different: Bode was invited to a Masonic convention, which was over when he arrived.

So this conspiracy thesis lacked any basis. Nevertheless, Barruel's and Robison's works became great successes. In German-speaking countries, the short-lived conservative magazine Eudämonia (1795–1798) in particular spread the theory that the Illuminati would continue to exist even after the dissolution of the order, that they were responsible for the French Revolution and that they were a current threat.

In the United States, there was a real Illuminati panic in 1798 when Puritan clergy like Jedidiah Morse and Timothy Dwight IV applied Robison and Barruel's conspiracy theories to the domestic political situation in their country. For them, the Democratic Republican Party and in particular its founder Thomas Jefferson , who had stayed in Paris from 1785 to 1789, represented the current version of the Illuminati, who supposedly not only the moderate-conservative government of the Federalist Party under President John Adams , but wanted to abolish all Christianity at once. One result of this widespread fear was the Alien and Sedition Acts , which made it difficult for foreigners to acquire American citizenship and made it a criminal offense for any "false, scandalous and malicious publication against the US government".

The anti-Illuminati conspiracy theory was charged anti-Semitically at the end of the 19th century by claiming that World Jewry and Freemasons or Illuminati were pulling together or were ultimately identical. The English fascist Nesta Webster constructed the widespread theory in the 1920s that the Jews were behind the alleged Illuminati plots. In doing so, she tried to explain the October Revolution in Russia, the radicalization of the labor movement in Western countries as well and the emergence of supranational organizations such as the League of Nations . Webster and her successors rely on the anti-Semitic forgery of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion , in which the Freemasons were imagined as the cover organization of a Jewish world conspiracy. Right -wing and right-wing extremist groups and people continue to spread conspiracy theses about the Illuminati: for example the American John Birch Society , the Baptist preacher Pat Robertson and the conspiracy theorist Des Griffin .

The myth of the order's continued existence was nourished in the 20th century by a number of occult or theosophical groups, among others , who tried to stylize themselves as the Illuminati, who had supposedly disappeared underground for decades. In 1896, for example, the occultist Leopold Engel founded the World Association of Illuminati , which claimed the successor to Weishaupt's order. In 1929 this registered association was deleted from the Berlin register of associations. The sex-magical Ordo Templi Orientis , created in 1912, or the Illuminati von Thanateros , founded in 1978, try to align themselves with the Bavarian Illuminati, but they have nothing to do with the enlightened-rationalistic order of Weishaupt, Bodes and Knigges.

The German conspiracy theorist Jan Udo Holey (“Jan van Helsing”) has published several books about the Illuminati, in which he claims, for example, that they were Jewish “bloodsuckers” controlled by aliens who instigated World War II and prepared for World War III in order to achieve world domination known as the " new world order ". To this end, he cites the anti-Semitic forgery of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and ties in with similar conspiracy theories of National Socialism . Such paranoid fantasies are considered evidence of the close connection between right-wing extremism and parts of esotericism.

Fiction

The Illuminati are often depicted in popular novels , such as the Illuminatus trilogy! by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson , in Umberto Eco's The Foucault Pendulum or in Illuminati by Dan Brown . Here they are portrayed satirically or luridly as sinister villains, obscure conspirators or demonic world conspirators using the numerous conspiracy theories that are in circulation about the order. Although the novels by Shea, Wilson and Eco are interpreted as satires on conspiracy theories or polemics against all esotericism , these fictitious statements about the Illuminati are often mistakenly held to be true today. Dan Brown, for example, seriously linked them to the Ismailis and thus fed conspiracy theses that connect the Illuminati with Islamist terror . Also, Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) and Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) were not members, as Brown says, and they are not part of a millennia-old tradition of Celtic druids via assassins and templars with the aim of creating the umbilicus telluris (Latin for "navel of the earth").

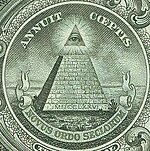

Particularly popular in some of these novels is the idea that the Illuminati agreed on secret signs and codes and used certain symbols to make their existence recognizable for initiates and resourceful "symbolologists", including the all -seeing eye , also as the closing stone of the unfinished Pyramid (→ Seal of the United States ) on the American one-dollar note, the number 23 and ambigrams . However, none of these symbols can be historically associated with the Illuminati; they only used one emblem, the owl of Minerva , symbol of wisdom.

Other media

The Illuminati is often alluded to in films, computer games and pieces of music. The high degree of familiarity of her name through conspiracy theories, in which she is made into a very secret and very powerful group, repeatedly predestines her for the role of the mysterious threat. Popular examples are:

- Movies: 23 - Nothing is what it seems , Lara Croft: Tomb Raider , Illuminati , The Whoopee Boys

- Card game: Illuminati

- Pen & Paper RPG : GURPS Illuminati

- Computer games: several games from the Deus Ex series , Resident Evil 4 , The Secret World , Grand Theft Auto V

- Piece of music: 23 from Welle: Erdball .

literature

- Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment. Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-486-54171-4 .

- Richard van Dülmen : The Illuminati secret society. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-7728-0674-0 .

- Richard van Dülmen: The Illuminati secret society. In: Journal for Bavarian State History. 36: 793-833 (1973).

- Stephan Gregory: Knowledge and Secret: The Experiment of the Illuminati Order. Stroemfeld, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-86109-183-7 .

- Ludwig Hammermayer : Lines of development, results and perspectives of recent Illuminati research. In: Alois Schmid, Konrad Ackermann (Hrsg.): State and administration in Bavaria. Festschrift for Wilhelm Volkert on his 75th birthday. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-10720-6 , pp. 421-463.

- Jochen Hoffmann: Significance and function of the order of the Illuminati in Northern Germany. In: Journal for Bavarian State History. 45/1982, pp. 363-380.

- Christoph Hippchen: Between conspiracy and prohibition. The Order of Illuminati in the mirror of German journalism (1776–1800). Böhlau, 1998, ISBN 3-412-04296-X .

- Reinhard Markner, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk , Hermann Schüttler: The correspondence of the Illuminati order. Volume 1: 1776-1781. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-484-10881-9 . Volume 2: January 1782 – June 1783. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-029500-9 .

- Wilhelm Mensing: Illuminatism at the Freemason Convention in Wilhelmsbad from July 14th to September 1st 1782. In: Journal for Bavarian State History. 41/1978, pp. 271-292.

- Helmut Reinalter (Ed.): The Order of Illuminati (1776–1785 / 87). A political secret society of the Age of Enlightenment. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-631-32227-5 .

- Jan Rachold (Ed.): The Illuminati. Sources and texts on the Enlightenment ideology of the Illuminati Order (1776–1785). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1984, DNB 850116341 .

- Hans-Jürgen Schings : The brothers of the Marquis Posa. Schiller and the Illuminati secret society. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-484-10728-6 .

- Hermann Schüttler: The members of the Order of Illuminati 1776–1787 / 93. Ars Una, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-89391-018-2 . Cf. on this W. Daniel Wilson: On the politics and social structure of the Illuminati Order, on the occasion of a new publication by Hermann Schüttler. In: International Archive for Social History of German Literature 19 (1994), pp. 141–175.

- Hermann Schüttler: Two Masonic Secret Societies of the 18th Century in Comparison: Strict Observance and Order of Illuminati . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Cologne / Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 521-544.

- Eberhard Weis : The Order of Illuminati (1776–1786). With special consideration of the questions of its social composition, its goals and its continued existence after 1786. In: Helmut Reinalter (Hrsg.): Enlightenment and secret societies. On the political function and social structure of the Masonic lodges in the 18th century. Oldenbourg, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-486-54751-8 , pp. 87-108.

Web links

- Hermann Schüttler, Reinhard Markner, Markus Meumann, Olaf Simons: Research literature on the Illuminati Order. In: Gothaer Illuminati Encyclopedia Online.

- Josef Swoboda: The Ghost of the Illuminati Order - Conspiracy Theories and Real Conspiracies. In: Phase 2. 24/2007.

- Hans Georg Schmieg, Jens Scherbl, Christian Plank, Andreas Gündisch: Illuminati. Seminar paper. 2004. (PDF; 11 MB)

- Franz Josef Burghardt : The Illuminati Secret Society. Cologne 1988. (PDF; 4 MB)

- Marian Füssel: Weishaupts Gespenster or Illuminati.org revisited. On the history, structure and legend of the Illuminati Order. , 2000.

- German enlightened nobles as enlightened people 1776–1793. List of noble members at the Institute for German Aristocracy Research

- Illuminati, The New World Order & Paranoid Conspiracy Theorists (PCTs). In: Robert Todd Carroll: The Skeptic's Dictionary. (English)

- The Gotha Illuminati Research Base Research platform of the Gotha Research Center on the documentary tradition of the Order of Illuminati.

Individual evidence

- ^ Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, p. 150.

- ↑ Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk , Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 1: 1776-1781. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-484-10881-9 , p. XII f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online); Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748-1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter : (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, ISBN 978-3-96285-004-3 , p. 329 (here the quote).

- ↑ Adam Weishaupt: Pythagoras: or, reflections on the secret world and government art. ] 1st volume, 1st [- 3rd] section, 1790. (full text online) ; quoted by Karl RH Frick : The Enlightened. Gnostic-theosophical and alchemical-Rosicrucian secret societies. Marix-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-006-4 , p. 455.

- ↑ Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748 to 1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 330.

- ↑ a b Jeffrey L. Pasley: Illuminati. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia. Volume 1, ABC Clio, Santa Barbara 2003, ISBN 1-57607-812-4 , p. 336 .

- ↑ Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk, Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 1: 1776-1781. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-484-10881-9 , p. XV (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 73 f .; Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748-1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 330.

- ↑ Quoted from Dolf Lindner: Ignaz von Born, Master of True Harmony: Viennese Freemasonry in the 18th Century . Österreichischer Bundesverlag, Vienna 1986, p. 152.

- ↑ Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk, Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 1: 1776-1781. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-484-10881-9 , pp. XVIII ff. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ "Spartacus" was Weishaupt's religious name. In truth, he had founded the Order before his inauguration into Freemasonry. Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748-1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 330.

- ↑ Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk, Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 1: 1776-1781. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-484-10881-9 , p. XX f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk, Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 2: January 1782 – June 1783. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-029500-9 , p. IX. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Karl-Heinz Göttert : Knigge or: From the illusions of decent life. dtv, Munich 1995, p. 55 f .; Ralf Klausnitzer: Poetry and Conspiracy. Relationship Sense and Sign Economy of Conspiracy Scenarios in Journalism, Literature and Science 1750–1850 . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-097332-7 , pp. 147 f., 182 f. and 193–214 (here the quote), (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Ludwig Hammermayer: The Wilhelmsbad Freemason Convention of 1782. A climax and turning point in the history of the German and European secret societies. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Heidelberg 1980, ISBN 3-7953-0721-X , p. 42 ff .; Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk, Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 2: January 1782 – June 1783. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-029500-9 , pp. XI – XIV (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Franz Josef Burghardt : The Illuminati Secret Society . Cologne 1988, p. 19 f. ( online (PDF; 3.8 MB), accessed on February 21, 2013).

- ↑ Monika Neugebauer-Wölk: Reich Justice and Enlightenment. The Reich Chamber of Commerce in the Illuminati network. Wetzlar 1993.

- ^ Hermann Schüttler: The communication network of the Illuminati. Aspects of a reconstruction. In: Ulrich Johannes Schneider (Hrsg.): Cultures of knowledge in the 18th century . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019822-5 , pp. 141–150, here p. 144 (accessed from De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Karl-Heinz Göttert: Knigge or: From the illusions of decent life. dtv, Munich 1995, p. 59 f.

- ↑ Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk, Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 2: January 1782 – June 1783. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-029500-9 , pp. XV – XVIII. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748 to 1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 331.

- ↑ Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk, Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 2: January 1782 – June 1783. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-029500-9 , pp. XVIII – XXI (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748 to 1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 331.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Göttert: Knigge or: From the illusions of decent life. dtv, Munich 1995, p. 66 f.

- ↑ Horst Möller : Princely State or Citizen Nation? Germany 1763-1815 . Siedler, Berlin 1994, p. 506.

- ^ Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, p. 82.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society 1700-1815. Volume 1: From Feudalism of the Old Empire to the Defensive Modernization of the Reform Era. 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-32261-7 , p. 324.

- ^ Ralf Klausnitzer: Poetry and conspiracy. Relationship Sense and Sign Economy of Conspiracy Scenarios in Journalism, Literature and Science 1750–1850 . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-097332-7 , p. 273 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Christoph Hippchen: Between conspiracy and prohibition. The Order of Illuminati in the mirror of German journalism (1776–1800) . Böhlau, Weimar / Cologne / Vienna 1998, p. 13; Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 255 ff.

- ^ Andreas Kraus: History of Bavaria. From the beginning to the present. 3. Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2004, p. 350.

- ^ Ralf Klausnitzer: Poetry and conspiracy. Relationship Sense and Sign Economy of Conspiracy Scenarios in Journalism, Literature and Science 1750–1850 . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-097332-7 , pp. 274 ff. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online)

- ↑ Renate Endler: On the fate of the papers of Johann Joachim Christoph Bode. In: Quatuor Coronati yearbook. 27/1990, pp. 9-35.

- ↑ Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748 to 1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 331.

- ^ Ralf Klausnitzer: Poetry and conspiracy. Relationship Sense and Sign Economy of Conspiracy Scenarios in Journalism, Literature and Science 1750–1850 . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-097332-7 , p. 275 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online)

- ^ Hermann Schüttler: Two Masonic Secret Societies of the 18th Century in Comparison: Strict Observance and Order of Illuminati . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 521-544, here pp. 530 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online); Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748-1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 331.

- ^ Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): Johann Joachim Christoph Bode: Journal of a trip from Weimar to France in 1787. Ars Una, Munich 1994; Claus Werner: Le voyage de Bode à Paris en 1787 et le «complot maconnique». In: Annales historiques de la révolution française 55 (1987), pp. 432-445; John David Seidler: The Conspiracy of the Mass Media. A cultural history from the bookseller plot to the lying press . transcript, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-8376-3406-8 , p. 124.

- ↑ Marco Frenschkowski : The secret societies. A cultural and historical analysis . Marix, Wiesbaden 2007, p. 131.

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter: The world conspirators. All of which you should never know. Ecowin Verlag, Salzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7110-5070-0 , p. 80.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1700-1815. Volume 1: From Feudalism of the Old Empire to the Defensive Modernization of the Reform Era. 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 324.

- ^ Also for the following see addendum of further original writings, which concern the Illuminati sect in general, but strangely the founder of the same Adam Weishaupt, who was professor at Ingolstadt . Leutner, Munich 1787, pp. 44–120 ( online at Google Books , accessed December 25, 2018); Helmut Reinalter: The world conspirators. All of which you should never know. Salzburg 2010, pp. 76-80.

- ↑ W. Daniel Wilson: "Political Jacobinism as it lives and breathes"? The Order of Illuminati and revolutionary ideology: First publication from the "Higher Mysteries." In: Lessing Yearbook XXV (1993) pp. 174 ff.

- ↑ Richard van Dülmen (Ed.): The Illuminati Secret Society. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart 1977, p. 183.

- ↑ Monika Neugebauer-Wölk: The utopian structure of social target projections in the Illuminati League . In: the same and Richard Saage (ed.): The politicization of the utopian in the 18th century. From utopian system design to the age of revolution . Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 978-3-11-096539-1 , pp. 180 and 184 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, pp. 106-119; Helmut Reinalter: The world conspirators. All of which you should never know. Salzburg 2010, pp. 76-80.

- ^ Hermann Schüttler: Two Masonic Secret Societies of the 18th Century in Comparison: Strict Observance and Order of Illuminati . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 521–544, here p. 532 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1700-1815. Volume 1: From Feudalism of the Old Empire to the Defensive Modernization of the Reform Era. 4th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 324 f.

- ↑ Pierre-André Bois: Illuminatism as a step into modernity . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 545–556, here p. 549 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter: Illuminati Conspiracy . In: the same: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 145.

- ↑ Monika Neugebauer-Wölk: The utopian structure of social target projections in the Illuminati League . In: the same and Richard Saage (ed.): The politicization of the utopian in the 18th century. From utopian system design to the age of revolution . Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 978-3-11-096539-1 , p. 181 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, p. 75 f.

- ^ Hermann Schüttler: Two Masonic Secret Societies of the 18th Century in Comparison: Strict Observance and Order of Illuminati . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 521–544, here pp. 542 ff. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Monika Neugebauer-Wölk: The utopian structure of social target projections in the Illuminati League . In: the same and Richard Saage (ed.): The politicization of the utopian in the 18th century. From utopian system design to the age of revolution . Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 978-3-11-096539-1 , p. 179 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Karl-Heinz Göttert: Knigge or: From the illusions of decent life. Munich 1995, p. 51 f .; Helmut Reinalter: The world conspirators. All of which you should never know. Salzburg 2010, p. 81 ff.

- ↑ Reinhard Markner: Introduction. To the historical introduction . In: the same, Monika Neugebauer-Wölk, Hermann Schüttler (Ed.): The correspondence of the Order of Illuminati. Volume 2: January 1782 – June 1783. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-029500-9 , p. XV. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Marian Füssel : Mystery and Discursivation. On the dialectic of publicity and secrecy in the Illuminati order . In: Kornelia Hahn (Ed.): Public and Revelation. An interdisciplinary media discussion . UVK, Konstanz 2002, p. 29 ( online , accessed December 25, 2018).

- ^ W. Daniel Wilson: Privy Councilors Against Secret Societies. An unknown chapter in the classic romantic history of Weimar. Metzler, Stuttgart 1991, p. 63.

- ↑ Reinhart Meyer : North German Enlightenment versus Jesuits. In: Hans Erich Bödeker and Martin Gierl (eds.): Beyond the discourses. Enlightenment Practice and the World of Institutions from a European Comparative Perspective. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, p. 155.

- ↑ Peggy Stubley: Johann Adam Joseph Weishaupt (1748 to 1830) . In: Helmut Reinalter: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 331.

- ↑ Pierre-André Bois: Illuminatism as a step into modernity . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 545–556, here pp. 547 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Sieglinde Graf: Illuminati . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Volume 16: Idealism - Jesus Christ IV . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1987, p. 82 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Monika Neugebauer-Wölk: Debates in the Secret Room of the Enlightenment. Constellations of knowledge gain in the Order of the Illuminati . In: Wolfgang Hardtwig (Ed.): The Enlightenment and its world effect. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010, pp. 17–46, here pp. 26 ff.

- ↑ Reinhart Koselleck: Criticism and Crisis . A study of the pathogenesis of the bourgeois world. 11th edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 3-518-27636-0 , p. 76.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Göttert: Knigge or: From the illusions of decent life. Munich 1995, p. 54 f .; Helmut Reinalter: Illuminati conspiracy . In: the same: (Ed.): Handbook of conspiracy theories. Salier Verlag, Leipzig 2018, p. 148.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Göttert: Knigge or: From the illusions of decent life. Munich 1995, p. 59 f.

- ^ Manfred Agethen: Secret society and utopia. Illuminati, Freemasons and German Late Enlightenment . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987.

- ^ Sieglinde Graf: Illuminati . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Volume 16: Idealism - Jesus Christ IV . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1987, p. 83. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Quoted from Monika Neugebauer-Wölk: Debates in the Secret Room of the Enlightenment. Constellations of knowledge gain in the Order of the Illuminati . In: Wolfgang Hardtwig (Hrsg.): The Enlightenment and its world effect. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010, pp. 17–46, here p. 21.

- ↑ Pierre-André Bois: Illuminatism as a step into modernity . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 545–556, here pp. 549 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hermann Schüttler: Two Masonic Secret Societies of the 18th Century in Comparison: Strict Observance and Order of Illuminati . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 521–544, here p. 525 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Marco Frenschkowski: The secret societies. A cultural and historical analysis . Marix, Wiesbaden 2007, p. 131.

- ↑ Due to multiple affiliations, the numbers do not add up to 1000%; Hermann Schüttler: Two Masonic Secret Societies of the 18th Century in Comparison: Strict Observance and Order of Illuminati . In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 521–544, here pp. 534–541 (accessed via De Gruyter Online); see. on a narrow statistical basis Eberhard Weis : The Order of Illuminati (1776–1786). With special consideration of the questions of its social composition, its goals and its continued existence after 1786. In: Helmut Reinalter (Hrsg.): Enlightenment and secret societies. On the political function and social structure of the Masonic lodges in the 18th century. Oldenbourg, Munich 1989, pp. 87-108.

- ↑ Eberhard Weis: The Order of Illuminati (1776–1786). With special consideration of the questions of its social composition, its goals and its continued existence after 1786. In: Helmut Reinalter (Hrsg.): Enlightenment and secret societies. On the political function and social structure of the Masonic lodges in the 18th century. Oldenbourg, Munich 1989, pp. 87-108, here p. 100.

- ^ Manfred Agethen: Freemasonry and popular enlightenment in the 18th century. In: Erich Donnert (Ed.): Europe in the early modern times. Festschrift for Günter Mühlpfordt on his 75th birthday . Böhlau, Weimar / Köln / Wien 1997, ISBN 3-412-00797-8 , pp. 487–508, here pp. 500–505 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ W. Daniel Wilson: Privy Councilors Against Secret Societies. An unknown chapter in the classic romantic history of Weimar. Metzler, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-476-00778-2 .

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Schings: The brothers of the Marquis Posa. Schiller and the Illuminati secret society . Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-484-10728-6 , pp. 13 and 21 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ John David Seidler: The Conspiracy of the Mass Media. A cultural history from the bookseller plot to the lying press . transcript, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-8376-3406-8 , p. 121.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Schings: The brothers of the Marquis Posa. Schiller and the Illuminati secret society . Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-484-10728-6 , pp. 20 and 181 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Quoted from Jan Assmann: Religio duplex. Egyptian Mysteries and European Enlightenment. Verlag der Welteligionen im Insel Verlag, Berlin 2010, p. 244.

- ^ Jan Assmann: Religio duplex. Egyptian Mysteries and European Enlightenment. Verlag der Welteligionen im Insel Verlag, Berlin 2010, pp. 297 and 305.

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter: Mozart and the secret societies of his time . StudienVerlag, Innsbruck 2016 online at Google Books

- ↑ Karl Hepfer: Conspiracy Theories. A philosophical critique of unreason . transcript, Bielefeld 2015, p. 105.

- ↑ Jürgen Roth , Kay Sokolowsky : The dagger in the robe. Plots and delusions from two thousand years ago. KVV Konkret, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-930786-21-4 .

- ↑ Helmut Reinalter: The world conspirators. All of which you should never know. Salzburg 2010, pp. 81 and 86 f.

- ^ John Robison: About secret societies and their dangerousness for state and religion. B. Culemann, Königslutter 1800 ( translated into German )

- ↑ a b Jeffrey L. Pasley: Illuminati. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia. Volume 1, Santa Barbara 2003, p. 337 .

- ^ Claus Werner: Le voyage de Bode à Paris en 1787 et le «complot maconnique». In: Annales historiques de la révolution française 55 (1987), pp. 432-445.

- ^ Klaus Epstein : The Genesis of German Conservatism. Princeton University Press, Princeton / New Jersey 1966, Chapter 10.

- ↑ Quotation (“any false, scandalous, and malicious writing against the government of the United States”) after the legal text on constitution.org, accessed on February 16, 2013. Vernon Stauffer: New England and the Bavarian Illuminati. Columbia University Press, New York 1918, pp. 229-320.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz : The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The legend of the Jewish world conspiracy. CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-53613-7 , p. 37 .

- ↑ Marku Ruotsila: Antisemitism. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia . ABC Clio, Santa Barbara 2003, Volume 1, pp. 82 f.

- ↑ Daniel Pipes: Conspiracy. Fascination and power of the secret. Gerling Akademie Verlag, Munich 1998, p. 247 ff .; Jeffrey L. Pasley: Illuminati. In: Peter Knight (Ed.): Conspiracy Theories in American History. To Encyclopedia. Volume 1, Santa Barbara 2003, p. 339 .

- ^ David Marley: Pat Robertson: An American Life. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7425-5295-1 , p. 174 .

- ↑ Michael Barkun: A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. University of California Press, 2006, ISBN 0-520-24812-0 , p. 54 .

- ^ Arnon Hampe: Jan Udo Holey. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbook of Antisemitism Volume 2: People. de Gruyter Saur, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-598-44159-2 , p. 375 (accessed via De Gruyter Online); Angelika Benz: Illuminati. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Volume 5: Organizations, Institutions, Movements . de Gruyter Saur, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-027878-1 , p. 322 (accessed via De Gruyter Online); Friedrich Paul Heller, Anton Maegerle : The language of hatred: right-wing extremism and folk esotericism, Jan van Helsing, Horst Mahler. Butterfly, 2001, ISBN 3-89657-091-9 , pp. 132 f .; Wolfgang Wippermann : Agents of Evil. Conspiracy theories from Luther to today . be.bra. Verlag, Berlin 2007, pp. 146–149.

- ↑ Caroline Klima: The great handbook of the secret societies. Freemasons, Illuminati and other leagues . Tosa, Vienna 2007, p. 213.

- ↑ Randall Clark: Conspiracy Theories as a Form of Public Mourning. In: Ray Broadus Browne, Arthur G. Nea (Eds.): Ordinary Reactions to Extraordinary Events. Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 2001, p. 41 f .; Max Kerner, Beate Wunsch: World as a riddle and a secret? Studies and materials on Umberto Eco's Foucault pendulum . Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-631-49480-7 .

- ↑ Illuminati. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Handbook of Antisemitism 03: Organizations, Institutions, Movements. Berlin 2012, p. 323 .

- ↑ Marco Frenschkowski: The secret societies. A cultural and historical analysis. Marixverlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86539-926-7 , p. 131.