dialectic

Dialectic is an inconsistently used expression in Western philosophy . The word dialectic is derived from ancient Greek διαλεκτική (τέχνη) dialektiké (téchne) "(art of) conversation", synonymous with Latin (ars) dialectica "(art of) conversation" (compare also dialogue ). Since the 18th century, another use of the word has gained acceptance: The doctrine of the opposites in things or the concepts as well as the discovery and removal of these opposites. In purely schematic terms, dialectics in this newer sense can be described in a simplistic way as a discourse in which a thesis as an existing conception or tradition is contrasted with a demonstration of problems and contradictions as an antithesis , resulting in a solution or a new understanding as a synthesis .

This classical instrument of rhetoric , known from antiquity , is used as a methodical method of finding the truth, to analyze and describe contradictions between concept and object, discussion participants or real contradictions in nature or society . The stylistic and analytical tool is used primarily in discussions, philosophical writing and in cabaret monologues .

For Hegel , dialectics is the method of knowledge opposed to metaphysics , and at the same time the inner regularity of the self-movement of thought and the self-movement of reality.

In dialectical materialism , dialectics is the science of the most general laws of motion and development of nature, society and thought.

Term / etymology

The word dialectic originates from the Greek media deponent διαλέγεσθαι dialégesthai that "a conversation lead" means. Dialegesthai is made up of the prefix dia- and the root leg- , which is contained in logos (basic meaning: speech ; also: bill , relationship , reason ) and legein ( say, talk ). The infinitive dialegesthai is used in Herodotus , Thucydides and Gorgias in the sense of conversation . Dialectics appears first in Plato as an adjective and as a noun and here and subsequently becomes a technical term for a method or to designate a science.

Dialectic is an expression that was not used uniformly even in ancient times. Up until modern times, however, it essentially retains the meaning of a conversation-based discipline or method used to establish truth. The term has had many other uses since the 18th century.

history

Antiquity

In ancient philosophy, the term dialectic denotes a method or discipline for acquiring or checking knowledge. Initially, and mostly, a question-and-answer situation is assumed. Arguments are questions in a conversation situation or are perceived as being in a conversation situation. The progress of the argument results solely from the fact that the premises stated by the questioner are affirmed or denied by the respondent (or are thought to be affirmed or denied). According to Aristotle ([fr. 65] after Diog. IX 25ff and VIII 57) the inventor of the dialectic is said to have been Zeno of Elea .

Plato

For the first time the expression dialectic is found in Plato . He separates the dialectic from the rhetorical monologue and the eristics of the sophists , which he regards as a method for asserting any opinion. In the early dialogues , dialectics is an argumentative form of conducting a conversation: Socrates turns an untested opinion of a proponent on its head or refutes it using the elenchos (test) . Often these conversations end in aporia , i. That is, after the dialectical conversation it is only proven that the old thesis is to be rejected, but a new one has not (yet) been found.

In later dialogues (particularly the Phaedo , the Politeia , the Phaedrus, and the Sophistes ), dialectic is Plato's fundamental science. It provides the methods with which an appropriate distinction is made in philosophy and knowledge about the ideas - especially about the idea of the good - is to be obtained: the hypothesis procedure and the dihairesis procedure .

The term dialectic contains several dimensions of meaning in Plato. Since there are very many, sometimes strongly contradicting, interpretations of the dialogues, it makes sense to quote a few key passages in the text on the dialectic. The following classification is not canonical, but is intended as a guide.

First , dialectic simply means philosophy and philosophical attitude:

"You name the dialectician who grasps the concept of everything that is essence (ton logon hekastou lambanonta tês ousias)."

"Who knows how to ask (erôtân) and answer (apokrinesthai), do you call him something different from dialecticians?"

"But it is probably more dialectical (to dialektikôteron) to answer not only in a true way (talêthê apokrinesthai), but also in ways that the questioner confirms that he understands."

Second , dialectic means - in a more specific sense - "research into ideas". Here the term partly coincides with the modern topics of logical analysis ( Dihairesis literally means "division", "separation"), semantics and syntax:

"[...] The separation according to genre (to kata genê diarheisthai), that one neither considers the same term (eidos) for another nor another for the same, do we not want to say that this belongs to dialectical science (dialektikê epistêmê)? - We want to say that. - Anyone who knows how to do this properly will notice one idea (idea) spread out in all directions through many individually separated from one another, and many different from one another externally encompassed and again one linked together through many wholes in one, and finally many completely separated from one another (dihorismenas). This then means to what extent everyone can enter into community and to what extent they do not know how to differentiate according to type. "

Third , dialectic is what is known today as metaphysics, namely the search for the basic structures and foundations of the world. From Hypothesis method one can speak in this context because the dialectic is precisely the unquestioned conditions - hypotheses - the other sciences studied:

“Only the dialectical procedure (dialektikê methodos) [...] removes the prerequisites and makes its way there: to the beginning yourself in order to gain a firm footing. And it gradually pulls the eye of the soul out of the barbaric morass in which it was actually buried and directs it upwards. As a staff member and co-leader, she takes the above-mentioned subjects [namely arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, harmony] to the rescue. "

For Plato, dialectics has to do with contradictions insofar as the occurrence of a contradiction must lead to the testing of the hypotheses or the argumentation. Because of the principle of contradiction, which Plato himself explicitly formulated in the Dialogue Politeia , Der Staat , such a contradiction is excluded:

"It is obvious that the same thing (tauton) will never do opposites and suffer (tanantia poiein ê paschein) at the same time, at least not taken in the same sense and in relation to one and the same."

Aristotle

The first explicitly systematically elaborated dialectic by Aristotle is available in his Topik . Dialectics is a methodological instruction manual which he describes as follows:

"[...] a procedure by means of which we will be able to deduce from recognized opinions ( endoxa ) about every problem presented and, if we represent an argument ourselves, not to say anything contradicting."

Dialectical arguments are deductions . They do not differ formally from scientific ones, but only in the nature of their premises : Scientific premises are special, namely “true and first sentences”, dialectical, however, recognized opinions, i.e. H. Sentences which “are believed to be correct by either all or most or the best known or the experts and by these either by all or most or the best known and most recognized”.

The dialectician operates in the argumentation with various argumentative tools and in particular with the topes. The latter are argumentation schemes for certain argumentation scenarios that are found and applied by the dialectician according to the properties of the predicates used in the premises .

Dialectics according to Aristotle is useful as mental gymnastics, in encounters with the crowd and by playing through opposing positions when discussing philosophical problems.

Hellenistic philosophy

The Megarian school was called "dialectical" because it was particularly characterized by dealing with logical problems and fallacies. In some cases, the approach there was also called " eristic ". The skeptical embossed Academy of Arcesilaus to invalidate summed dialectic as a method on, every thesis, any assertion of knowledge with an argument for the opposite thesis. According to Stoic usage, dialectics (in addition to rhetoric) is part of the Stoic “logic” (in the broader sense than it is understood today). It is defined (presumably by Chrysippus ) as “the science of what is true, of what is false, and of what is neither”. Dialectics is thus the Stoic's instrument for distinguishing between true and false ideas and includes, in particular, stoic epistemology. The division of the Stoic dialectic into a field “About the voice” and “About what is designated” shows, however, that other contemporary disciplines such as phonetics, semantics, philosophy of language and stylistics also fall under it.

middle Ages

Boethius takes up the topics of Aristotle and Cicero and develops special maxims of argument from the locus . Berengar von Tours , William of Shyreswood and Petrus Hispanus develop further approaches.

Part of the scholastic method of the Middle Ages was dialectic as an art of disputation , which was also one of the seven liberal arts . This dialectical eloquence found its excellent expression in the quaestiones and the scholastic sums.

In the narrower sense, one calls the scholastic method a particularly methodical procedure, which was specifically trained by Abelard and which was used by most of the scholastics according to his example. It consists in the dialectical juxtaposition of the arguments for and against a particular view. The method is therefore named with the catchphrase “pro et contra” (pros and cons) or also “sic et non” (yes and no), the title of the Abelard book in question.

Modern times

Transcendental dialectic in Kant

For Kant , the transcendental dialectic is an essential section in the Critique of Pure Reason . Here he dealt critically with statements about reality that want to get along completely without experience . He described such forms of explanation, which are based on purely formal logic , as "dazzling work" and as an "apparent art of thinking". Through such “rationalizations” dialectics become a pure logic of appearance (KrV B 86-88). In terms of content, the transcendental dialectic deals with the three basic themes of metaphysics : freedom of will , immortality of the soul and the existence of God (KrV B 826). With an epistemological intent, Kant argued in the paralogisms that the mind-body problem could not be solved. The antinomies also show that empirical experience does not allow conclusions to be drawn about the unconditional. The following theorems can be proven formally logically, but the opposite can just as easily be proven (KrV B 454 ff):

- "The world has a beginning in time, and according to space it is also enclosed within limits."

- "Every compound substance in the world consists of simple parts, and everywhere there is nothing but the simple, or that which is composed of it."

- “Causality according to the laws of nature is not the only one from which the phenomena of the world as a whole can be derived. It is still necessary to assume a causality through freedom to explain it. "

- "Something belongs to the world which, either as its part or its cause, is an absolutely necessary being."

Finally, in the critical examination of the proofs of God , he shows that the existence of a merely imagined object cannot be proven. God can be thought but not known. The "endless disputes of metaphysics" do not lead to any meaningful result in any of the three questions because they exceed the limits of human reason. Meaningful metaphysics can only deal with what the conditions of the possibility of knowledge are.

According to Kant

Kant's dialectic was regarded as closed by later philosophers such as Schopenhauer . Others assumed that Kant's view of dialectics could definitely be improved, such as Fichte and Schelling .

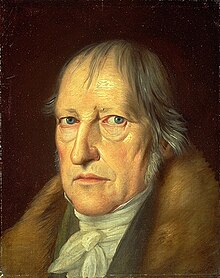

Hegel's dialectic

For Hegel , the ancient philosopher Heraclitus was an early dialectician. The Logos as the principle of the world is for Heraclitus in the dispute ( polemos "father of all things") as well. The constantly changing world is characterized by a battle of opposites, by the eternal contradiction of polarities . In contrast, there is a “deeper, hidden unity, a belonging together of the different”. Hegel connects his method with the concept of dialectic. Since the phenomenology of the mind , dialectical movement has been regarded as what is actually speculative, “the course of the mind in its self-apprehension.” In this, the dialectic is “the driving moment of the rational within the intellectual thinking, through which the intellect finally cancels itself.” What is often called Hegel's dialectic, is logic for him. The true or the concept, he also says the logically real , essentially consists of three moments. These cannot be viewed separately from one another.

"The form of logic has three sides: α) the abstract or intelligent, β) the dialectical or negatively rational, γ) the speculative or positively rational."

- The finite, intelligent moment: the mind posits something as being.

- The infinitely negative, dialectical moment: The reason recognizes the one-sidedness of this provision and denies them. Such a contradiction arises . The conceptual opposites negate each other, i. H. they cancel each other out.

- The infinitely positive, speculative moment: Reason recognizes in itself the unity of the contradicting determinations and brings all previous moments together to a positive result, which are canceled out in it.

In speculation, the negated opposites turn into a positive result. The core of his method is negation. It unfolds the dialectical representation of the “unprecedented, self-moved and self-determined development of the thing itself , according to the omnis determinatio est negatio ”. The negation of the negation or double negation is something positive again. Hegel calls it affirmation .

In his work on the theory of science, following Heinrich Rickert and Emil Lask, Max Weber contrasted analytical logic with emanatic logic , which he understood as a conceptual logic that was based on Hegel's dialectic.

Materialistic dialectic

Karl Marx separated from the standpoint of Hegelian idealism and used dialectics on a historical-materialist basis as a method, as a dialectical method of representation , to criticize political economy . According to a sentence by Friedrich Engels, the return to materialism is putting the dialectic of Hegel "from the head on which it stood on its feet again".

“We again grasped the concepts of our head materialistically as the images of real things, instead of real things as images of this or that level of the absolute concept. […] But with this the dialectic of terms itself only became the conscious reflex of the dialectical movement of the real world, and with it the Hegelian dialectic was turned upside down, or rather turned from the head on which it stood. "

Marx expresses himself in the economic-philosophical manuscripts from 1844 about the Hegelian dialectic, in general and how it is elaborated in Hegel's “Phenomenology” and “Logic”, and their reception by the Young Hegelians . Ludwig Feuerbach is the only one who has shown a critical attitude towards this and can be regarded as the overcomer of Hegel. Because Feuerbach had proven that Hegel's philosophy continued theology.

“The appropriation of the essential forces of man, which have become objects and foreign objects, is firstly only an appropriation that takes place in consciousness, in pure thinking, i. e. What happens in abstraction is the appropriation of these objects as thoughts and thought movements, which is why in “Phenomenology” - despite its thoroughly negative and critical appearance and despite the criticism actually contained in it, which often anticipates later developments - already the uncritical one Positivism and the equally uncritical idealism of later Hegelian works - this philosophical dissolution and restoration of the existing empiricism - lies latently, as a germ, as a potency, as a secret. "

Hegel's idealism opposed Feuerbach to true materialism and real science. The "unhappy consciousness", the "honest consciousness", the struggle of the "noble and mean consciousness" etc., these individual sections contained the critical elements - but still in an alienated form - of entire spheres such as religion, the state.

The great thing about Hegel's “phenomenology” and its end result - the dialectic of negativity as the moving and generating principle - is that Hegel sees human self-generation as a process, objectification as objectification, as alienation and as the abolition of this alienation; that he grasps the essence of work and understands the objective, true, because real person as the result of his own work.

For Marx nothing other than social reality is the basis for the "course of the matter itself". It is not the development of concepts or the spirit that determines reality, but rather the actions of people, oriented towards the actual satisfaction of needs and the interests determined by economic conditions , determine their thinking and thus the development of ideas.

According to Marx, the materialist dialectic is both logical and historical. The contradiction does not unite two opposites to a higher third as in Hegel, but triggers a process of historical enforcement of the logically better and stronger relationships that work in human practice as the driving force of history. In social practice, the human will shapes social reality by deliberately influencing social processes and the existing conditions in accordance with historically determined laws of social development.

In the section “Basic Laws of Dialectics” in his work Dialectics of Nature, Friedrich Engels differentiates between objective and subjective dialectics in accordance with the materialistic dialectic approach:

“The dialectic, the so-called objective, prevails in the whole of nature, and the so-called subjective dialectic, the dialectical thinking, is only a reflex of the movement in opposites, which asserts itself everywhere in nature, which is caused by their constant conflict and their eventual dissolution into each other, resp. into higher forms, just condition the life of nature. "

The materialist dialectic in Marx and Engels can thus be understood as the methodology of Marxism for the foundation of scientific socialism . In the further history of communist philosophy it becomes a fundamental component of historical as well as dialectical materialism , which, however, does not always coincide with one another in Friedrich Engels, Lenin or dogmatically very coarse with Stalin . The dialectical laws exist here initially independently of consciousness. Through the revolutionary reorganization of the conditions and relations of production and the possible exploitation of those laws, these then exist in interaction with consciousness.

Dialectic of Critical Rationalism

Karl Popper interpreted Hegel's dialectic within the framework of formal logic according to the following scheme:

P 1 → VT → FE → P 2

The scheme marks the progress of science: Based on a problem P 1 from world 3 , an initially purely hypothetical preliminary theory VT is set up. This is checked (e.g. empirically), untenable elements are eliminated in an error elimination FE. The result is not absolute knowledge, but a more elaborate problem P 2 . FE assumes that logical contradictions must be avoided, as otherwise it is not possible to eliminate theoretical elements that contradict the arguments given in the theory test.

Popper particularly emphasized his insistence on the "law of contradiction" in his 1937 article What Is Dialectic , in which he criticized the unimproved dialectical method for its willingness to come to terms with contradictions. Popper later claimed that Hegel's acceptance of contradictions was, to some extent, responsible for facilitating the rise of fascism in Europe by encouraging and trying to justify irrationalism. In section 17 of his 1961 addendum to the Open Society , originally titled Facts, Standards, and Truth: A Further Criticism of Relativism , Popper refuses to relativize his criticism of the Hegelian dialectic, arguing that it plays a major role played in the fall of the Weimar Republic by contributing to historicism and other totalitarian modes of thought and for lowering traditional standards of intellectual responsibility and honesty. This view has u. a. Walter A. Kaufmann objected.

Modern formalization of the dialectic

The philosopher and logician Gotthard Günther presented, as part of his theory of polycontexturality, an approach, which has been expanded several times since 1933, to formalize the Hegelian dialectic in the context of a multi-valued logic , whereby he critically set himself apart from Jürgen Habermas .

Dialectics in the Frankfurt School

The collection of essays Dialectics of the Enlightenment , written by Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno and published in the USA in 1944, is today considered a key work of the Frankfurt School. The work, which contains theses on "why mankind, instead of entering a truly human condition, sinks into a new kind of barbarism", understands the historical process of the Enlightenment as dialectical, but diagnosed as being in its supposed conclusion in modernity in a frozen form they form the basis for a new barbarism that manifested itself in fascism in the first half of the 20th century.

Adorno describes his understanding of knowledge about social reality in the book of the same name, published in 1966, as Negative Dialectic . It is a criticism of the theoretical conclusion of philosophy to a system . Philosophy-historical basic considerations are a socially critical correlate .

For Adorno, a method based on the concept of dialectics is a prerequisite for a theory that remains open to what has not yet been conceptually grasped.

“The contradiction is not what Hegel's absolute idealism inevitably had to transfigure it for: not something Heraklite-like essence. It is an index of the falsehood of identity, of the dissolution of what is understood in the concept. The appearance of identity, however, is inherent in thinking itself in its pure form. Thinking means identifying. […] It lies secretly in Kant, and was mobilized against him by Hegel, that the concept of the otherworldly in-itself is null and void as something completely indefinite. Nothing is open to the consciousness of the semblance of conceptual totality but to break through the semblance of total identity immanently: according to its own measure. But since that totality is built up according to logic, the core of which is formed by the proposition of the excluded third party, everything that does not fit into it, everything qualitatively different, takes on the signature of contradiction. "

The philosophical problem of the relationship between thinking or language and object, which Hegel solved by thinking of the concept as potentially identical with the object (and thus Kant's thing in itself as an empty set), is thought by Adorno as thinking itself produces the appearance of a complete comprehension of reality and that which is not grasped in the coherence of all thinking at one point in time (“totality”) is contained in this as a contradiction.

Positivism dispute

The discussion in the context of the positivism dispute was shaped by the Hegelian understanding of the term, its modification by Marx and the criticism of these positions. According to the self-understanding of the dialecticians, this method captures the basic structure of reality. Only she can truly grasp this in its entirety. The contradiction here lies in the nature of thinking and thus also in the matter itself. Because systematic and deductive thinking must categorically reject and reject contradictions, since it is inseparably linked to logic at the base, it cannot recognize this truth. From this point of view it is incompatible with dialectical thinking.

Habermas explained this problem as follows:

“In this respect, the dialectical concept of the whole does not fall under the justified criticism of the logical foundations of those Gestalt theories which in their field generally perish investigations according to the formal rules of analytical art ; and yet it transcends the boundaries of formal logic, in whose shadowy dialectic itself cannot appear otherwise than as a chimera "

criticism

Hegel's dialectical approach has been criticized by contemporaries and those who followed. Schopenhauer spoke disparagingly of Hegel's philosophy as " Hegelei ". Since Kierkegaard , a protest against the system of dialectics has not become unusual. Dialectical materialism was also hotly contested, especially in the political discussion of the 20th century. In particular, the question arose as to why economic society inevitably presents itself as a class struggle that is progressively developing.

The analytic philosophy criticized first of all the dialectical language from the perspective of linguistic criticism after the linguistic turn has not adhered to the standards of formal logic. It can even be said that hostility to, or susceptibility to, dialectics is one of the things that in the twentieth century divides Anglo-American philosophy from so-called "continental tradition" - a gap that few contemporary philosophers (including Richard Rorty ) have dared to bridge.

The analytical philosopher Georg Henrik von Wright gave dialectics a cybernetic interpretation by interpreting dialectics as a chain of negative feedbacks, each leading to a new equilibrium. Unlike the dialecticians, von Wright understands the use of logical terms within dialectics as metaphorical, with "contradiction" standing for real conflicts. In doing so, he takes into account the criticism of the dialecticians, according to which they would be subject to a mix-up between logical contradictions, which can only exist between sentences and propositions, and real opposites, for example between physical forces or social interests.

literature

- Theodor W. Adorno : Three studies on Hegel . Frankfurt am Main 1963

- Theodor W. Adorno: Negative Dialectic . Frankfurt am Main 1966

- Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer : Dialectics of the Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1969, ISBN 3-596-27404-4

- Werner Becker: Hegel's concept of dialectic and the principle of idealism . Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne / Mainz 1969

- Rüdiger Bubner : On the matter of dialectics . Stuttgart 1980.

- Rüdiger Bubner: Dialectics as Topics . Frankfurt 1990

- Thomas Collmer : Hegel's Dialectic of Negativity - Investigations for a self-critical theory of dialectic . Focus Verlag Gießen, 2002; ISBN 3-88349-501-8

- Ingo Elbe : Dialectics - peculiar logic of a peculiar object? Also in: U. Freikamp u. a. (Ed.): Criticism with method? Research methods and social criticism . Berlin 2008.

- Werner Flach: Hegel's dialectical method , in: Hans-Georg Gadamer: Heidelberger Hegel-Tage 1962, Bonn 1964

- Johannes Fried (ed.): Dialectics and rhetoric in the early and high Middle Ages. Reception, tradition and social impact of ancient scholarship primarily in the 9th and 12th centuries (= writings of the Historisches Kolleg . Colloquia, vol. 27) Munich 1997, ISBN 978-3-486-56028-2 ( digitized version )

- Gotthard Günther : Contributions to the foundation of an operational dialectic , 3 volumes. Meiner, Hamburg, I 1976. II 1979. III 1980. (Collection of papers since 1940 on the replacement of the Aristotelian logic of being with a dialectical logic of reflection)

- Jens Halfwassen : The ascent on the one hand. Investigations on Plato and Plotinus . Stuttgart 1992 (contributions to archeology, vol. 9).

- Erich Heintel : Outline of the Dialectic. A contribution to the importance of fundamental philosophy , vol. 1: Between philosophy of science and theology , Darmstadt 1984

- Robert Hot : The great dialecticians of the 19th century: Hegel, Kierkegaard, Marx. Cologne 1963

- Hans Heinz Holz : Dialectics. Problem history from antiquity to the present. (5 volumes) Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2011.

- Joachim Israel : The term dialectic. Epistemology, language and dialectical social science . Hamburg 1979

- Leo Kofler : The Science of Society. Outline of a methodology of dialectical sociology. 1944. Frankfurt am Main: Makol 1971

- Karl R. Popper : What is dialectic? (PDF; 325 kB). In: Ernst Topitsch (Ed.): Logic of the Social Sciences 5, pp. 262–290, ( 5 1968)

- Arthur Schopenhauer : Eristic Dialectic or The Art of Being Right . Haffmans Verlag, January 2002

- Jürgen Ritsert : Dialectical Figures of Argumentation in Philosophy and Sociology. Hegel's Logic and the Social Sciences , Münster 2008.

- Jürgen Ritsert: Small textbook of dialectics , Darmstadt 1997.

- Konrad Utz: The necessity of chance. Hegel's speculative dialectic in the “science of logic” . Paderborn 2001

- Herbert A. Zwergel: Principium contradictionis. The Aristotelian justification of the principle of the contradiction to be avoided and the unity of the First Philosophy, Meisenheim 1972

- Hans-Ulrich Wöhler: Dialectics in Medieval Philosophy , Berlin 2006.

- Dieter Wolf : On the relationship between dialectical and logical contradiction (104 kB; PDF). In: The dialectical contradiction in capital. A contribution to Marx's theory of value , Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-87975-889-1

Web links

- Julie E. Maybee: Hegel's Dialectics. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Friedrich Engels: Dialectics of Nature

- Lorenz B. Puntel : Can the term dialectic be clarified (pdf; 307 kB), Munich 1996

- Dieter Wolf : On the method of ascending from the abstract to the concrete (pdf; 84 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kosing, A .: Marxist dictionary of philosophy. -Verlag am Park, Berlin. - 2015

- ↑ Georg Klaus / Manfred Buhr (ed.): Marxist-Leninist Dictionary of Philosophy , Rowohlt, Hamburg 1972, ISBN 3-499-16155-9 .

- ^ Plato, Meno 75 d .

- ↑ Plato, Politeia , 534e.

- ^ Rolf Geiger: dialegesthai. In: Christoph Horn / Christof Rapp: Dictionary of ancient philosophy. Munich 2002, p. 103.

- ↑ Cf. AA Long / DN Sedley: The Hellenistic Philosophers. Texts and comments, translated by Karlheinz Hülser, Stuttgart 2000, p. 222.

- ^ Rolf Geiger: dialegesthai , in: Christoph Horn, Christof Rapp: Dictionary of Ancient Philosophy , Munich 2002, p. 103.

- ↑ quoted from: Aristoteles: Topik translated and commented by Tim Wagner and Christof Rapp, Stuttgart 2004.

- ↑ Aristotle, Topic I, 1, 100a 22; quoted from: Aristoteles: Topik translated and commented by Tim Wagner and Christof Rapp, Stuttgart 2004.

- ↑ Aristotle, Topic I, 2, 100b 25 ff .; quoted from: Aristoteles: Topik translated and commented by Tim Wagner and Christof Rapp, Stuttgart 2004.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios , 7.42; quoted from: AA Long, DN Sedley: The Hellenistic Philosophers. Texts and comments . Translated by Karlheinz Hülser, Stuttgart 2000, p. 215.

- ↑ Cf. and see Lu De Vos: Dialektik , in: Paul Cobben et al. (Ed.): Hegel-Lexikon . WBG, Darmstadt 2006, p. 183.

- ^ Lu De Vos: Dialektik , in: Paul Cobben et al. (Hrsg.): Hegel-Lexikon . WBG, Darmstadt 2006, p. 182.

- ↑ More detailed concept and classification of logic, § 79.

- ↑ “α) Thought as understanding remains with the fixed determination and the difference between the same and others; Such a limited abstract is for him to exist and exist for itself. "( G. W. F. Hegel: ibid., § 80. )

- ↑ "β) The dialectical moment is the own cancellation of such finite determinations and their transition into their opposing ones." ( G. W. F. Hegel: ibid., § 81. )

- ↑ “Abolition and the abolished (the ideal) is one of the most important concepts of philosophy, a basic definition that recurs everywhere, the meaning of which is to be grasped in a definite way and especially to be distinguished from nothing. - What is canceled does not become nothing. Nothing is immediate; something that is canceled, on the other hand, is something that is mediated, it is that which does not exist, but as a result that proceeded from a being; therefore it still has in itself the determinateness from which it comes. Picking up has the double meaning in the language that it means as much as to keep, to receive and at the same time as much as to stop, to put an end to it. Storage itself already includes the negative that something is taken from its immediacy and thus from an existence open to external influences in order to preserve it. - So what is canceled is at the same time something that has been preserved, which has only lost its immediacy, but is therefore not destroyed. ” Science of logic , preface to the second edition; Works 5, 114. “The cancellation represents its true double meaning which we have seen in the negative; it is a negation and a preservation at the same time; the nothing, as nothing of this, preserves the immediacy and is itself sensual, but a general immediacy. ”, Phenomenology of Spirit, A. II., Works 3, p. 94. Hegel's use of“ lifting ”closes as it does from places like the above results in several moments of meaning. In the Hegel literature and Hegel school - as early as the middle of the 19th century, for example with Johann Eduard Erdmann - three of them are often named: negating ( tollere ), preserving ( conservare ) and raising to a higher level ( elevare, sublevare ) . These can still be found in German dictionaries and were also taken up by historically influential interpreters such as Martin Heidegger . The text finding in Hegel is, however, more complex, such as, in a nutshell, Lu De Vos: Art. Aufbaren , in: Paul Cobben et al. (Ed.): Hegel-Lexikon . Darmstadt: WBG 2006, 142-144 explained. For a representation that is more strongly committed to the three-dimensional scheme, cf. MJ Inwood: Art. sublation , in: A Hegel dictionary, Wiley-Blackwell 1992, ISBN 0-631-17533-4 , 283-287.

- ↑ "γ) The speculative or positive-reasonable conceives the unity of the determinations in their opposition, the affirmative, which is contained in their dissolution and their passing over." ( G. W. F. Hegel: ibid., § 82. )

- ↑ Cf. and see Konrad Utz: Negation , in: Paul Cobben et al. (Hrsg.): Hegel-Lexikon . WBG, Darmstadt 2006, p. 335f.

- ↑ MEW vol. P. 293 .

- ↑ Marx, p. 197. Digital Library Volume 11: Marx / Engels, p. 765, cf. MEW Vol. 40, p. 568.

- ↑ p. 206. Digital Library Volume 11: Marx / Engels, p. 774, cf. MEW Vol. 40, p. 573.

- ↑ a b Marx: Economic-philosophical manuscripts from 1844, p. 207. Digital library, Volume 11: Marx / Engels, p. 775, cf. MEW Vol. 40, p. 573.

- ↑ See Karl Marx / Friedrich Engels - Works. (Karl) Dietz Verlag, Berlin. Volume 20. Berlin / GDR. 1962. “Dialectics of Nature” , pp. 481–508.

- ^ Karl Popper: Objective knowledge , campe 1992 Hamburg, p. 310

- ^ Karl Popper: Objective knowledge , campe 1992 Hamburg, p. 170

- ↑ Chapter 12 of the second volume of The Open Society and Its Enemies .

- ^ Walter A. Kaufmann : The Hegel Myth and Its Method . From Shakespeare to Existentialism: Studies in Poetry, Religion, and Philosophy (Boston: Beacon Press, 1959), pp. 88–119.

- ^ Gotthard Günther , Fundamentals of a New Theory of Thought in Hegel's Logic , Meiner, Hamburg ²1978, ISBN 3-7873-0435-5

- ↑ Gotthard Günther: Critical remarks on the current philosophy of science - On the occasion of Jürgen Habermas: To the logic of the social sciences . in: Soziale Welt, 1968, vol. 19, pp. 328–341. ( online , PDF, 69 kB)

- ↑ Adorno / Horkheimer: Dialectic of Enlightenment , Frankfurt 1988, p. 1

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno: Negative Dialektik , Frankfurt am Main 1966, p. 15

- ^ Logic of the Social Sciences , 5.