Max Weber

Maximilian Carl Emil "Max" Weber (born April 21, 1864 in Erfurt , † June 14, 1920 in Munich ) was a German sociologist and economist . Although he was trained as a lawyer , he is considered one of the classics of sociology as well as of the entire cultural , social and historical sciences .

He taught as a private lecturer and associate professor at the University of Berlin (1892–1894) and as a full professor at the Universities of Freiburg (1894–1896), Heidelberg (1897–1903), Vienna (1918) and Munich (1919–1920). Due to illness, he interrupted his university teaching in Heidelberg for many years, but during this time he developed an extraordinarily productive journalistic and journalistic activity. In addition, for the Sunday jour fixe he gathered well-known scientists, politicians and intellectuals, whose meeting established the so-called “Myth of Heidelberg” as an intellectual center.

With his theories and coining terms, he had a great influence in particular on economic , domination , legal and religious sociology . Even if his work is fragmentary in character, it was developed from the unity of a leitmotif: Occidental rationalism and the disenchantment of the world that it brings about . He assigned a key position in this historical process to modern capitalism as the “most fateful power of our modern life”. The choice of this research focus showed a closeness to his antipode Karl Marx , which also earned him the name “the bourgeois Marx”.

Weber's name is linked to the Protestantism-capitalism thesis , the principle of freedom of value judgment , the term charisma , the state's monopoly of violence and the distinction between ethics of conviction and responsibility . A learned treatise on the sociology of music emerged from his preoccupation with the “medium of redemption art” . Politics was not only his field of research, but he also expressed himself as a class-conscious citizen and committed to current political issues of the German Empire and the Weimar Republic out of liberal convictions . As an early theorist of bureaucracy , he was named one of the founding fathers of organizational sociology via the detour US-American reception .

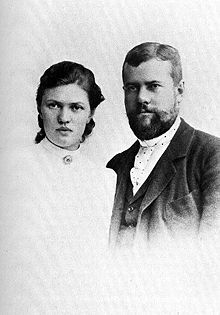

Max Weber's wife Marianne Weber was politically active as a women's rights activist, wrote the first and for decades only biography of her husband after his death and published some of his important works posthumously.

Life

Max Weber was a self-confident member of the middle class . In his inaugural speech in Freiburg in 1895, he introduced himself to his audience as follows: "I am a member of the bourgeois classes, I feel like one and am educated in their views and ideals". According to Jürgen Kaube, that was it with regard to “property, political position, scholarship, education and lifestyle”. Wolfgang J. Mommsen described him as a “class-conscious bourgeois” and the “bourgeois Marx ” who, like hardly anyone else, had so consistently championed bourgeois ideals “as this descendant of French Huguenots ”. As a scientist, according to Werner Gephart , he could call himself a lawyer, economist, historian, sociologist and art scholar with good reason.

Youth and studies

Max Weber was born on April 21, 1864 in Erfurt as the first of eight children, six of whom (four sons and two daughters) reached adulthood. His parents were the lawyer and later a member of the Reichstag for the National Liberal Party, Max Weber senior. (1836–1897) and Helene Weber, b. Fallenstein (1844–1919), both Protestants with Huguenot ancestors; Helene Fallenstein was a granddaughter of the businessman Cornelius Carl Souchay . His brother Alfred , born in 1868 , also became a political economist and university professor of sociology, while his brother Karl, born in 1870, became an architect. Max Weber was through the maternal line nephew of Hermann Baumgarten and cousin of Fritz and Otto Baumgarten ; his paternal uncle was the textile manufacturer Carl David Weber .

Max Weber grew up in a relatively intact family, “whose cohesion was manifested not least in disputes”. He was considered a problem child who had meningitis at the age of two . He asserted the rights of the firstborn at an early age and felt in the family as a mediator of disputes between parents and children. He mastered the school requirements "effortlessly and with flying colors". At thirteen he read works by the philosophers Arthur Schopenhauer , Baruch de Spinoza and Immanuel Kant , but also fiction such as works by Goethe .

After graduating from the Königliche Kaiserin-Augusta-Gymnasium in Charlottenburg , Weber studied law , economics , philosophy , theology and history in Heidelberg , Strasbourg , Göttingen and Berlin from 1882 to 1886 . In his major in law was one of his major fields of study Roman law and the prescribed for those legal training in Germany Pandectist , one of Roman legal texts systematized on the collection law, which is also the basis for the 1900 adopted Civil Code was formed. His studies were only partially interrupted by his military service in 1883/1884 as a one-year volunteer in Strasbourg, where he was able to attend the historical seminars of his uncle Hermann Baumgarten. At first he experienced the military service as "dull" and ended it as a reserve officer. During his military service in Strasbourg, he spent a lot of time with his uncle's family, “an old 48 liberal” who became a kind of surrogate father and mentor for him. His everyday student life was characterized on the one hand by hard work, extensive reading and intellectual contacts, on the other hand by the student life of the time between scales and excessive drinking habits. Weber was a member of the student union Burschenschaft Allemannia ( SK ), from which he announced his resignation in a letter dated October 17, 1918. In his resignation letter to the chairman of the Philistine Commission , he emphasized the merits of the association for the "care of manhood", but criticized the "spiritual inbreeding" and "restriction of personal intercourse" of the association that had prompted him to make this decision.

After passing the first state law examination on May 15, 1886 at the Higher Regional Court of Celle , Max Weber began a four-year legal traineeship in Berlin, which he completed on October 18, 1890 with the second state examination. In 1886 he returned to his parents' house in Berlin for financial reasons, where he lived until his wedding in 1893. Even during the clerkship Weber was with the dissertation The development of Solidarhaftprinzips and the Investment Fund of the general partnership from the household and commercial communities in the Italian cities on 1 August 1889 the Friedrich-Wilhelms University in Berlin to Dr. jur. (with the grade magna cum laude ). His doctoral supervisor was the lawyer and commercial lawyer Levin Goldschmidt . During the public disputation the famous intervention of Theodor Mommsen took place : "Son, there you have my spear, it is getting too heavy for my arm." In this first publication, the legal historian Gerhard Dilcher discovered "later basic figures of Weber's sociological thought", such as " Community ”and“ Society ”as well as the“ explanatory paradigm of rationalization ”.

University career and political positions

In February 1892 he completed his habilitation in commercial law and Roman law with August Meitzen in Berlin, with the immediately following appointment as a private lecturer . Weber's habilitation thesis was entitled The Roman Agrarian History in Its Significance for State and Private Law . After this “brilliant legal career” he was appointed associate professor for commercial law and German law at the law faculty of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in October 1893, at the age of 29, and continued to represent his sick teacher Levin Goldschmidt. In the same year he married his cousin Marianne Schnitger in Oerlinghausen , who later became active as a women's rights activist, writer and politician. The marriage remained childless.

Also in 1893 Max Weber was first co-opted into the committee of the Verein für Socialpolitik . This was preceded by the large empirical study The situation of agricultural workers in East Elbe Germany , which appeared in the association's series of publications in 1892. Weber had already joined the association in 1888 and was a member of it until the end of his life. Together with his younger brother Alfred, who participated with him in the association's inquiry into the selection and adjustment of the workforce in large-scale industry , he belonged to the younger, left-liberal generation of the association, not to the older generation of the so-called Catholic Socialists around Gustav Schmoller and Adolph Wagner . In the debates of the association they both appeared "eloquently as disputable dioscuri ".

In 1893 Weber joined the Pan-German Association , which represented a nationalist policy. When he was unable to assert himself in the so-called “Poland question” in 1899 by calling for the borders to be closed for Polish migrant workers , he left the organization. In his resignation letter of April 22, 1899, Max Weber expressly states the question of Poland as the reason for his resignation and complains that the Pan-German Association did not demand the complete exclusion of Poles with the same vehemence with which he campaigned for the expulsion of the Czechs and Danes had used. In this respect, it failed because the peasant members of the Pan-German Association, who put the overcoming of the agricultural labor shortage in the foreground, were able to assert their interests.

As early as 1894, Max Weber was appointed to a chair for political economy at the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg . There he gave the academic inaugural address on May 13, 1895, The Nation State and National Economic Policy , which was published in the same year. In 1896 he was appointed the successor of his academic teacher Karl Knies , one of the most renowned economists, to the chair for economics and finance at the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg . In the summer semester of 1897, he began teaching in Heidelberg. During his mother's visit in June 1897, there was a scandal with his father, who had traveled with him because he would not let his wife travel alone. In the presence of the mother and Mariannes, the son discharged his long-pent-up rage about the father's authoritarian-patriarchal behavior towards the mother and declared that he no longer wanted to have anything to do with the father. "A son holds court day over the father", Marianne Weber summed up the dispute. Only a few weeks later, the father died without any reconciliation.

In the 1890s, Max Weber was a participant in several meetings of the Evangelical Social Congress and supported Friedrich Naumann and the National Social Association he founded , which he had joined as a member in 1896.

Task of teaching and scientific work

Weber had to limit his teaching activities in 1898 because of a nervous condition which the psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, who teaches in Heidelberg, diagnosed as " neurasthenia from years of overwork". Between 1898 and 1900 he spent several months in sanatoriums, but the cures were unsuccessful. Since 1900 he no longer taught, in 1903 he gave up the professorship entirely. Until 1918 he lived as a private scholar on the interest income from family assets. It was only with the establishment of the Archive for Social Science and Social Policy , whose editing he took over in 1904 together with Edgar Jaffé and Werner Sombart , that a new activity began for him, with which he resumed his journalistic work with large treatises. The “Objectivity” of sociological and socio-political knowledge (1904) and Protestant ethics and the spirit of capitalism (1904 and 1905) appeared in the very first issues .

Previously, in the fall of 1904, he had taken his wife on a three-month trip to the United States, where he visited Protestant congregations, the Chicago slaughterhouses, Indian schools, and the Tuskegee Institute, attended land auctions and worship services. He also met the black scientist WEB Du Bois , whom he valued and whom he had already met in Berlin. He left hardly any aspect of American society unseen. These impressions led Weber to increasingly reject racially oriented explanations for historical and social contexts. Six years later, Weber publicly recalled the encounter with the “gentleman” Du Bois, in order to contradict ideologues of the concept of race at the Frankfurt Sociologentag 1910.

From 1909 Weber devoted himself intensively to the conception of a large-scale new handbook, the Outline of Social Economics . As his own contribution to it, Economy and Society appeared posthumously in 1922 . In 1909 he founded the German Society for Sociology (DGS) together with Rudolf Goldscheid and Ferdinand Tönnies , Georg Simmel and Werner Sombart , of which Ferdinand Tönnies became its first president. In contrast to the Verein für Socialpolitik , which wanted to intervene in social reality, the establishment of the association was intended to move towards theoretical issues. Marianne Weber commented on the founding of the society: "Sociology was not yet a special science, but focused on a whole of knowledge, therefore in touch with almost all sciences." From then on Weber finally called himself a sociologist. But the bitter debates about the value-free postulate at the sociologists' days in 1910 and 1912 led to disappointment and resignation and his departure from society.

The so-called “Sunday Circle” (Marianne Weber), a discussion group that took place after Weber's move to Heidelberg in 1910 in the grandparents' “Fallensteinvilla” at Ziegelhäuser Landstraße 17, was of great importance for the design of Max Weber's social environment. Scientists, politicians and intellectuals from Heidelberg and from outside took part in the Sunday Jour fixe, among them: Ernst Troeltsch , Georg Jellinek , Friedrich Naumann , Emil Lask , Karl Jaspers , Friedrich Gundolf , Georg Simmel, Georg Lukács , Ernst Bloch , Gustav Radbruch , Theodor Heuss . Also educated women like Gertrud Jaspers, Gertrud Simmel, the women's rights activist Camilla Jellinek and the first generation of Heidelberg students (among them Else Jaffé ) were among the regular guests. The so-called "Myth of Heidelberg" was founded not least through this meeting as an intellectual center.

In the spring of 1913 and 1914 Weber spent a month each in Ascona on Monte Verità to cure, lose weight and at the same time assist an acquaintance (Frieda Gross) in a complicated process that spanned many years. He saw the colorful world of life reformers , “magical women” and anarchists who gathered at Monte Verità as an “oasis of purity”, and from there he greeted his wife as “Max who was devoured into strange fabulous worlds” .

In 1909 Max Weber became an extraordinary member of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences , from 1918 a foreign member.

First World War

At the beginning of the First World War , Max Weber was a disciplinary officer of the hospital commission in Heidelberg for a year. He shared the national optimistic mood of late summer 1914 with all his heart (“This war is great and wonderful”, he wrote to Karl Oldenberg and Ferdinand Tönnies). At the end of 1915, Weber began active journalism, primarily for the Frankfurter Zeitung , with which he spoke out in favor of a peace of understanding without annexations as well as parliamentarization and democratization of the German Reich as the war continued . In 1917 he took part in two cultural conferences at Lauenstein Castle , which the publisher Eugen Diederichs had organized to re-orientate himself after the war. His violent dispute with the conservative journalist Max Maurenbrecher was recorded for the Whitsun conference on “The meaning and task of our time” (May 29–31, 1917) . At the autumn conference on the “Leader Problem in the State and in Culture” (September 29th - October 3rd) he gave the opening lecture The Personality and the Order of Life .

In the summer semester of 1918 Weber resumed his teaching activity with the provisional acceptance of a call from the University of Vienna to the Chair of Political Economy - "to test my regained health," as he informed the responsible Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs. As early as the middle of the semester, he announced that he wanted to limit his teaching activity in Vienna to three months. His lecture was titled Positive Critique of the Materialist Concept of History . During this time he held at the invitation of enemy propaganda Abwehrstelle as part of a "patriotic education program" in June of the last year of the war against kuk -Offizieren a presentation on socialism . In May 1918 Parliament and Government appeared in the reorganized Germany , a political "polemic of academic character and tone" as a diagnostic application of his political sociology.

After the end of the war

After the war ended, Weber was one of the founding members of the left-liberal German Democratic Party (DDP), for which he wanted to run for the constituent national assembly . In December 1918 he was an expert advisor to the constitutional deliberations in the Reich Office of the Interior under the direction of Hugo Preuss and in May 1919 to the peace negotiations at Versailles under the direction of Count Brockdorff-Rantzau .

On April 1, 1919, he was appointed as successor to Lujo Brentano's Munich chair for the professorship for social science, economic history and national economy. He started teaching late in the summer semester because of his political obligations. In the winter semester of 1919/1920 he gave the lecture Outline of Universal Social and Economic History . It was to be his last college that he was allowed to complete. In July 1919 he was elected a full member of the historical class of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences . Weber's Munich lectures were treated as "university events"; even colleagues, including Lujo Brentano and Carl Schmitt , took part.

In July 1919 Max Weber was interrogated as a witness in the trials against the writer Ernst Toller and the economist Otto Neurath , both of whom he knew from the Lauenstein cultural conferences and who had played a leading role in the Munich Soviet Republic . Toller had already heard from Weber as a student in Heidelberg. Weber's positive statements about the ethical attitude of the two defendants contributed to their moderate conviction. He attested Toller the "absolute integrity of a radical ethicist".

Max Weber reacted with increasing alienation to the ongoing radicalization of the German right after the end of the war , which did not want to accept the defeat. The fact that nationalist student groups disrupted his lecture also had an effect. The reason was Weber's attitude in the case of Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley , the murderer of Kurt Eisner , the Bavarian Prime Minister. Weber defended the Count's “brave” deed, but said that “he should have been shot” so that he and not Eisner would live on as a martyr in memory. According to Joachim Radkau , Weber hated the "writers" at the head of the Munich council government "wholeheartedly".

Illness and death

At the end of May 1920 Weber was still working intensively on the corrections to the collected essays on the sociology of religion . After struggling with health problems for a long time, he fell ill with pneumonia in early June, possibly caused by the Spanish flu , and had to cancel the lectures on state sociology and socialism that had just started. He died of their consequences on June 14, 1920 in Munich-Schwabing, Seestrasse 3c (now 16). The funeral service, at which Marianne Weber gave a funeral speech, took place in Munich's Ostfriedhof , the later urn burial in the Heidelberg Bergfriedhof with the participation of around a thousand people. The grave of Weber and his wife is in Department E. On the death of Weber, a large number of almost hymnic obituaries were published in various organs, mourning the impressive personality, the patriotic German and the great intellectual.

His brother Alfred, who had wrestled with his older brother for life, survived him by 38 years; Like him, he was a staunch liberal and a representative of cultural sociology, but their two scientific paths could hardly be more different - one (Max) methodically oriented strictly to an ascetic and enlightening rationalism, the other (Alfred) for a vitalistically founded cultural sociology with desire fighting for wholeness and seen synthesis. Even in her youth, in 1887, Weber had certified his younger brother's tendency to "artistic and poetic" transfiguration of his doctrines, while drawing his conclusions from the same philosophy with "dreadful sobriety".

Max Weber as a politician

Weber never held a political office. Nevertheless, he was involved in political organizations such as the Pan-German Association and in the liberal parties founded by Friedrich Naumann ( National Social Association , German Democratic Party ). With his political essays and speeches, Weber sought to influence those in charge of politics and public opinion in the late German Empire, in World War I and in the revolutionary founding phase of the Weimar Republic. In a letter to Mina Tobler he confessed that politics was his “secret love”. In this regard, the younger philosopher Karl Jaspers , who was formerly involved in Weber's Heidelberg discussion group, found : "His thinking was the reality of a political person in every fiber, was a political will to act that served the historical moment".

With campaign speeches , journalistic articles in the daily press (including the Frankfurter Zeitung ) and lectures at socio-political and evangelical congresses, Weber, as a self-confident member of the bourgeois class, took a stand on important political issues of his era. In his book Max Weber and German Politics 1890–1920, Wolfgang Mommsen followed , recorded and critically commented on his work, speeches and writings as a politician in detail. Referring to the Freiburg inaugural address in 1895, Mommsen concluded that the “national power state” was Weber's political ideal. The speech served as the initial spark for the emergence of liberal imperialism in Wilhelmine Germany, and it was the liberal imperialists who made imperialism "socially acceptable" in Germany. As a “resolute supporter of imperialist ideals” he defended the expansive naval policy and advocated an overseas colonial policy .

He did not only consider the ethics of the Sermon on the Mount to be incompatible with political action, but also to be an "ethics of indignity". He opposed it "the gospel of the struggle [...] as a duty of the nation [...], the only way to greatness". In his speech Politics as a Profession , he postulated: “[...] you have to choose between the religious dignity that this ethic brings, and the male dignity that preaches something completely different: 'Resist evil, - otherwise you are for his Over violence shared responsibility. ”Weber felt that a nation had to want“ power above all ”as a historical necessity. He saw "the future of Germany as a powerful state" dependent in particular on the German bourgeoisie, which had been pushed into the center of social life during the transition from feudal agrarian society to capitalist industrial society.

During the German Empire and during the First World War

During the Empire , Weber joined the nationalist Pan-German Association in 1893, to which he belonged until 1899. He sympathized with his efforts to propagate an “active imperialist world politics ”. In several local groups of the association he gave lectures on the " Poland question ". With reservations he joined the National Social Association founded by Friedrich Naumann in 1896, a political party that pursued nationalist, social reform and liberal goals; In 1903 the association merged with the Liberal Association . Weber supported Naumann wherever he could. From the association he demanded a "consistent bourgeois policy, industrial progress and the national power state affirmative orientation". He went into court sharply with the “feudal reaction” (“I am considered an 'enemy of the Junkers '”, he confessed in a letter to the chairman of the Pan-German Association ). With Naumann in mind - based on the English model - a political alliance between the bourgeoisie and the rising strata of the working class was in mind.

He viewed Otto von Bismarck's role in German domestic and foreign policy extremely critically . As a “determined supporter of imperialist ideals” Weber strived for global political equality and an appropriate colonial empire. Bismarck largely ignored the possibilities of an overseas colonial policy and put Germany in the fatal position of "being the last in the queue of world powers aspiring to colonies ". In the 1918 publication Parliament and Government in the Reorganized Germany , he rigorously settled Bismarck's legacy. His "Caesarian rule" nipped the emergence of political leaders in the bud. He wanted the "political nullity of parliament and party politicians [...] and deliberately brought about". His departure left a power vacuum that was filled by a "theatrical emperor" and the Prussian civil servants. Using the example of British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone , he wished for a “leadership democracy with a machine” for German politics, that is, with the “ living machine that the bureaucratic organization with its specialization of trained specialist work, its delimitation of competencies, its regulations” and hierarchically graduated obedience relationships ".

During the war, Weber's journalistic activity was subject to the “self-imposed primacy of German national interest”; In the beginning he was by no means against annexations in principle , but against the immoderate war target programs of the right. In a letter published in the Frankfurter Zeitung in the summer of 1916, he spoke out against the “hiccups of a small clique” against the moderate Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg with the words: “[...] that this war is not being waged for the sake of adventurous goals , but only because and only as long as it is necessary for our existence ”.

During the November Revolution and in the Weimar Republic

For Wolfgang Mommsen, the years 1918 to 1920 were among Weber's “most intense direct involvement in daily politics”; but he did not come to any of the "longingly hoped for official use" in the political reorganization of Germany.

According to Mommsen, Weber had seen the revolution coming and was prepared for it, but the outbreak embittered him and despite the insight into the inevitability of what was happening, he took an extremely sharp stance against it in terms of political sentiments . In a speech in Karlsruhe in January 1919 he polemicized as follows: “ Liebknecht belongs in the madhouse and Rosa Luxemburg in the zoological garden”. According to Marianne Weber's testimony, he disapproved of the murder of Liebknecht and Luxemburg a few days later with the words: “The dictatorship of the street has come to an end in a way that I did not want. Liebknecht was undoubtedly an honest man. He called the street to fight - the street killed him ”. On the other hand , in a lecture in December 1918, he publicly stated that he was "close to the numerous, economically trained members of the social democracy, regardless of whether they were majority or independent socialists , indistinguishable". His various positions on socialism remained characterized by an ambivalence : on the one hand, he expected (and feared) from him the continuation, if not acceleration of the tendencies dominating his time to specialize and bureaucratize political and economic operations; on the other hand, he hoped that the socialists would reversed this development.

As a member of the Prussian Constitutional Committee , which met in Berlin from December 9th to 12th, 1918, he participated in the drafting of the future Weimar constitution. He was invited to participate in the Versailles peace delegation as an expert on the question of war guilt . He considered public confessions of guilt as "absolutely undignified and politically disastrous". One day before the start of the peace conference, the Frankfurter Zeitung published his article on January 17, 1919, on the subject of “war guilt” , in which he assigned tsarist Russia the main culprit for the First World War. He wrote to his wife from Versailles: "In any case, I do not take part in the guilt note if indignities are intended or permitted". He wrote to his sister Klara Mommsen, "The politician must make compromises [...] - the scholar must not cover them up".

At the urging of Naumann and Alfred Weber, Weber joined the left-liberal German Democratic Party (DDP), which Friedrich Naumann co-founded in 1918, and gave them extensive campaign speeches. Weber was the keynote speaker in no fewer than eleven election events. He advocated political cooperation with the social democrats . For a time he was a member of the board of the DDP. From its Frankfurt subdivision he was proposed as a candidate for the National Assembly; the proposal failed, however, due to internal resistance. When the party wanted to send him as a representative to the socialization commission formed at the time , he rejected the offer as an opponent of the socialization plans. When he took over the chair from Lujo Brentano in Munich, he ended his party political activities.

Max Weber and the women

In their biographical introduction to the Max Weber Handbook , the editors Hans-Peter Müller and Steffen Sigmund outline four women who were decisive for Weber's development: 1. his mother, whom he “adored and loved as a saint”, 2. his wife Marianne , with whom he entered into a "lifelong unbreakable relationship on the basis of a companion", 3. the Swiss pianist Mina Tobler , to whom he felt erotically sensual, 4. Else Richthofen-Jaffé , with whom he began a passionate relationship in 1917, which found expression in the famous interim comment on the collected essays on the sociology of religion in the form of an almost hymn-like eulogy on physical love. He dedicated one of the three volumes on the sociology of religion to each of the last three. According to his will, the publication Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft was to bear the dedication: “To the memory of my mother Helene Weber, born. Fallenstein 1844–1919 ”.

plant

According to Weber's scientific work, the challenges posed by the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche were:

“The honesty of a contemporary scholar, and above all of a contemporary philosopher, can be measured by how he feels about Nietzsche and Marx. Those who do not admit that they could not do vast parts of their own work without the work these two have done are deceiving themselves and others. The world in which we ourselves exist spiritually is largely a world shaped by Marx and Nietzsche. "

What was significant for Weber, as Marianne Weber learned, was that both thinkers, although opposing poles, agreed on one thing: in the endeavor to dissolve the valuations that stem from the diverse and contradicting mixture of “Christian culture”.

The influences of Nietzsche and Marx on Weber's work are difficult to grasp because Weber rarely gave references to their sources, but they are nevertheless considerable. The philosopher Wilhelm Hennis found that “Nietzsche's genius in the work of Max Weber” (the title of his essay) had left essential traces. He identified Weber's acceptance of Nietzsche's nihilism diagnosis (“God is dead”), from which he drew the most radical scientific conclusions, as elementary points of contact, and his adoption of Nietzsche's stylization of Christianity on the religion of love and brotherhood, the Sermon on the Mount which he saw in contradiction to his understanding of life as a struggle and a will to power . - Weber shared with Marx as a common research area “the 'capitalist' constitution of modern economy and society” and, like him, processed “enormous amounts of scientific material”. Karl Löwith sees the difference in the interpretation of capitalism in the fact that Weber analyzed it from the point of view of a universal and inescapable rationalization , whereas Marx, on the other hand, analyzed it from the point of view of a universal but revolutionary self-alienation . According to Marianne Weber's statement, Weber “paid great admiration to Karl Marx's ingenious designs”. He declared Marx to be “by far the most important case of ideal-type constructions”, his “laws” and development constructions ”are of unique heuristic significance. In a lecture on socialism to Austro-Hungarian officers in the last year of the war, 1918, he called the Communist Manifesto a "first-rate scientific achievement", a "prophetic document" which "had very fruitful consequences for science". He took over certain parts and terms from him (as from other authors whose works impressed him), which he worked on for his purposes, such as the concept of class . In other respects Weber is perceived as the antipode to Marx. He criticized the materialistic conception of history in the strongest possible terms, since he fundamentally rejected “any kind of unambiguous deduction” instead of concrete historical analysis.

Universal work

Max Weber is the youngest of the three founding fathers of German sociology (next to Tönnies and Simmel ). He is regarded as the founder of the sociology of domination and, alongside Émile Durkheim, as the founder of the sociology of religion . Along with Karl Marx, he is one of the most important classics of economic sociology . Weber also gave essential suggestions for numerous other sub-areas of sociology, such as legal , organizational and music sociology . Although, as a qualified lawyer, he later switched to research and teaching on economics and finally to understanding sociology as a cultural science with a claim to universal history, his work was strongly influenced by jurisprudence , especially constitutional law . In addition to his material historical analyzes, he made significant contributions to the methodology and theory of modern history. In his lecture Science as a Profession he mentions the “closest disciplines” to him: sociology, history, political economy and political science and those types of cultural philosophy which make their interpretation their task. For Wolfgang Schluchter , Max Weber's work has a fragmentary character, yet his texts were developed from the unity of a leitmotif: the peculiarity of Occidental rationalism with the consequence of “ disenchanting the world ” through predictability. Thomas Schwinn refers to a “three-part research program” Weber: methodology, theory, historical-material analysis.

Among his best-known and worldwide most widespread works of sociology are the treatise published in 1904 and 1905 under the title Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism , as well as his monumental work Economy and Society . The treatise on "Protestant ethics" was included in the collected essays on the sociology of religion , which appeared in three volumes in 1920/21. Economy and Society was only published in 1921/22 after his death by his wife Marianne Weber as the 3rd section of the outline of social economics and contains a comprehensive presentation of his conceptual and thought horizon.

In the specialist literature there are different proposals for structuring the varied and extensive works. Raymond Aron groups it into four categories: science , economic history , sociology of religion, and economy and society . Dirk Kaesler separates the presentation of the material analyzes from the "method" (i.e., in the narrower sense, science ). His two famous lectures ( science as a profession and politics as a profession ) on the one hand and his treatise on the sociology of music on the other do not find a proper place in this structure .

Science teaching

There is no consensus among Weber experts on the status of Weber's science . What is characteristic of the entire Weber work, complexity and "dazzling diversity", also applies to this. While the philosopher Dieter Henrich assumes a "unity of the science of science", the editor of several Weber writings, Johannes Winckelmann , sees it as merely a methodological "Sunday riding". The methodology is "just as little a prerequisite for fruitful work as the knowledge of anatomy a prerequisite for correct walking," Weber wrote in one of his methodological papers. He did not live to see a compilation of his “methodological-logical essays” published by Weber and his publisher Paul Siebeck. It was not until 1922 that Marianne Weber published a volume devoted to this subject area entitled Collected Essays on Science . In 1968 a third edition was published by Johannes Winckelmann that was critical of the text and expanded by a few text parts, which was published in the Max Weber Complete Edition as volumes I / 7: On the Logic and Methodology of Social Sciences and I / 12: Understanding Sociology and Freedom of Value Judgment was the central reference work for Weber's epistemological writings.

Cultural studies, social economics

The use of interdisciplinary terms such as “ cultural studies ” and “ social economics ” mark Weber's universal interest in knowledge . With the term “cultural studies” he referred in the same way to the historical as to the social sciences. With the term “social economics” he describes a social science concept that links history and theory, historical and theoretical school of economics by means of “understanding sociology”. The term "social economy" is also used today as social economy .

Methodical individualism

Weber is considered the founder of methodological individualism in the social sciences. Although the Weber student Joseph Schumpeter had previously coined the term for economics, it was theoretically elaborated by Weber, who declared it to be the basic principle of sociology. In his work on some categories of understanding sociology he formulates: “Terms such as 'state', 'cooperative', ' feudalism ' and the like denote for sociology, generally speaking, categories for certain types of human interaction and it is therefore its task to identify them 'Understandable' action, and that means, without exception, to reduce the action of the individuals involved. ”This is where sociology differs from jurisprudence , which under certain circumstances treats the state as a“ legal personality ”as well as the individual.

Concept formation and ideal type

Weber's conceptualizations are mainly used in sociology and political science as the basis for further research, for example his definitions of power and domination or charisma . The ideal type is one of them. Bernhard Quensel has meticulously followed up and shown how Weber consciously draws on the manner of legal terminology for the formation of sociological terms. Progressing from jurisprudence to legal history and sociology, he had arrived at the conceptualization and, based on Carl Menger's demand for real types, took over what Georg Jellinek described as an “ empirical type” in his general theory of the state , Jellinek in the same sense as after him Weber related. Ideal type is a theoretical construct that deliberately exaggerates certain aspects of social reality that are considered relevant and brings them into context. It is always based on logical and thoughtful conclusions and is obtained through observation of social phenomena and abstraction on the basis of general rules of experience. The aim of the ideal-typical construction is clear-cut terms with which empirical phenomena can be understood from the point of view of their cultural significance. Weber clearly speaks out against a normative consideration of the ideal type, the connection of reality and ideal type with the aim of comparison should not be confused with their evaluation. According to Dirk Kaesler, the ideal type is a “heuristic means” for guiding empirical research, a construction that serves to “systematize empirical-historical reality”; it is “not a hypothesis”, but wants to point the way for the formation of hypotheses.

The postulate of freedom of value judgment

In the history of sociology, the " value judgment dispute " before the First World War, and especially between Max Weber and Gustav Schmoller , occupies a prominent place, although it is not just about the problems of a particular discipline, sociology or economics, but about issues of "Basic definition of every scientific knowledge". According to Dirk Kaesler Weber's essays, the decisive points of reference in this controversy were The Objectivity of Sociological and Sociopolitical Knowledge (1904) and The Sense of 'Freedom of Values' in the Sociological and Economic Sciences (1917), as well as his speech Science as a Profession . Weber's postulate of freedom of value (judgment) is a "methodical principle" based on the distinction between statements of being and statements of should (descriptive and normative statements).

Social and economic history

In the winter semester of 1919/20 Weber gave the lecture Outline of Universal Social and Economic History at the University of Munich , which has only been handed down in notes and transcripts. Weber sees economic history as a "foundation [...] without whose knowledge, however, fruitful research into any of the great areas of culture is inconceivable". According to Stefan Breuer, it contains a condensed sum of Weber's studies on antiquity, the economic ethics of world religions, the development of the city, as well as the sociology of domination and law, and modern capitalism .

Agrarian Constitution

Weber dealt intensively with the "agricultural conditions" and the "agricultural constitution" in antiquity and in the Middle Ages . His early essays - The Roman Agrarian History in Its Significance for State and Private Law (1891) and Agricultural Conditions in Antiquity (1897, 3rd edition 1909) - take up this topic. He opens the content- related part of his economic history with an extensive chapter on household, clan , village and manorial rule (agricultural constitution) . Weber's scholarly preoccupation with antiquity has been of particular importance for most of his creative years since his earliest work.

Occidental rationalism

Weber's central theme was the reasons and phenomena of the “Occidental rationalism” that established itself in the western world as the cultural basis of economy and society at the latest by the end of the Middle Ages. Weber's first sociological essay, The Social Reasons for the Fall of Ancient Culture from 1896, can be seen as the foundation for his later work. The special development of the West is evident in a large number of areas of society. He names the development of the occidental city, the rational law , the rational business organization and administrative organization (“ bureaucracy ”), not least also the “methodical” organization of the everyday life of the members of society (“ way of life ”). Weber speaks of “spheres of values”, each of which has its own dynamic of rationality standards and values.

Rational capitalism

The lively discussion of historical capitalism among economic and ancient historians in the 19th century led Weber to specify his concept of capitalism. Against Marx, who identified the slave economy of antiquity as the most essential distinguishing feature from feudal-capitalist modernity, Theodor Mommsen and Eduard Meyer asserted a continuity from antiquity to modern times; It was always about capitalism, that is, money economy and competition in the market , Weber however concluded that the ancient economy was integrated into the political institutions, while in the modern age the political institutions are determined by the economy. In the modern age, the economy only became independent from politics and became autonomous. None of the characteristic institutions of modern capitalism ( bond , bond , share , bill of exchange , mortgage , Pfandbrief ) come from Roman law . England, the home of capitalism, never accepted Roman law .

According to the sociologist Johannes Berger , probably no other “cultural phenomenon” fascinated Weber more than modern capitalism; he was his "life theme". In the reservation for the collected essays on the sociology of religion , Weber characterizes capitalism “as the most fateful power of our modern life”. In the same place he describes the “specifically modern occidental capitalism” also as “bourgeois working capitalism”. As Berger notes, there are varying lists of characteristics in several places in Weber's work, but the focus is always on the “modern capitalist enterprise”, the “rational organization of formally free work”. Accordingly, there are two provisions that flow together in the definition of capitalist enterprise: (1) “Work by virtue of a formal voluntary contract on both sides” ( Economy and Society § 19), (2) Rational organization of contractual work. Work in a capitalist enterprise is only formally, but not materially free, since the execution of the work is under the command of capital. Whenever Weber differentiates between company and company (this does not always take place clearly), he understands the company "as a technical category, the company as a capital account". He uses "commercial enterprise" "in the event that the technical operating unit coincides with the business unit" or where "technical and economic (business) unit are identical".

Social change

From a universal historical perspective, Weber explains social change , which is synonymous with historical change, according to a "bi-polar model". According to this, interests dominate people's actions, but ideas that crystallize into worldviews act as “switches” for the path in which action moves. Weber differentiates between material and non-material interests, corresponding to his distinction between “purposeful rational” and “value rational” actions as defined in business and society (first chapter § 2).

The big speeches: science as a profession and politics as a profession

In November 1917 Weber gave the lecture Science as a Profession as part of a series entitled “Intellectual work as a profession” at the invitation of the Free Student Union . Here he explained in a completely free speech what "science" made into an independent "sphere of values" for the "increasing intellectualization and rationalization" of "Occidental culture" compared to religion, ethics or politics. In addition to the questions asked with passion, systematic work and the idea prepared on the basis of hard work make up the scientific activity. It is not only the necessary “inner vocation” that enables it, but “strict specialization” is also required of the (prospective) scientist; Weber described academic careers as a "game of chance" in an almost blatant manner.

In January 1919, in the same context, he gave the lecture on politics as a profession with the concluding, much-quoted phrase: "Politics means a strong, slow drilling of hard boards with passion and a sense of proportion at the same time" and thus formulated two of the three basic requirements for politicians: Passion in the sense of objectivity, responsibility in the interest of the matter of fact, "sense of proportion" as the necessary personal distance to things and people. In this lecture Weber also discussed the relationship between ethics of conviction and ethics of responsibility .

Wolfgang Schluchter characterizes the two speeches as “key texts for his answers to central questions of modern culture”, addressed to “academic and democratic youth”. According to him, they were speeches about “individual and political self-determination under the conditions of modern culture”.

Sociology ( economy and society )

In the compilation of the manuscripts by Marianne Weber and Johannes Winckelmann , economy and society have long been considered Weber's main sociological work. The editors of the complete edition have broken up the publication, which was originally divided into two parts, and the first part consisting of four chapters as a separate volume (I / 23) with the title Economy and Society. Sociology. Published unfinished 1919–1920 . It contains the chapters “I. Basic sociological terms "," II. Basic sociological categories of economic activity ”,“ III. The types of rule ”and“ IV. Stands and classes ”. Shortly before his death, Weber wrote these chapters for the Grundriß der Sozialökonomik . They contain the core structure of his sociology, although the fourth chapter remained unfinished. The chapters that originally formed the second part consisted of Weber's pre-war manuscripts, which Marianne Weber had added, calling the first part “abstract sociology” and the second part “concrete sociology”. The second part was published in the complete edition in separate (partial) volumes.

Social action as a basic sociological category

Weber describes sociology as "a science which aims to interpret social action and thereby explain its processes and effects". In this definition, the concept of social action marks the central (albeit not the only) fact that is constitutive for sociology as a science . Weber defines social action by the fact that it is based on the subjective meaning of the action and factually, in its course, on the behavior of others. He also differentiates between four ideal types of social action, depending on the type of reasons that can be asserted: purposeful, value-rational, affective and traditional action. For the two rational types of action it is true that the reasons can also be understood as the causes of the action. The types of action ultimately serve empirical research as causal hypotheses and as contrast films for the description of actual behavior.

Communityization and Vergesellschaftung

The categories Vergemeinschaftung and Vergesellschaftung are, despite all the differences, influenced by Ferdinand Tönnies ' first publication Community and Society , which Weber himself points out in Economy and Society . Elsewhere he speaks of "Tönnies' continuously important work".

While Tönnies uses the terms for a real historical sequence from the medieval “organic community ” to the modern “mechanical society ”, Weber relates the categories mainly to social action; He speaks of “community action” or “communalization” and of “social action” or “socialization”, but without always clearly distinguishing between them. This is clearly shown in his treatises on communities , for example when he formulates: In the market community , we face “as the type of all rational social action, socialization through exchange on the market”. Weber understands community as a synonym for social units of people under different aspects and differentiates between different "types of community according to structure, content and means of community action": house communities ( Oikos ), ethnic communities, market communities, political communities and religious communities. He has intensively researched the latter in particular. Hartmann Tyrell pointed out the "lack of a social term - in the singular as in the plural" ; the social whole is not an issue in Weber's sociology.

Sociology of domination

In Weber's last decade he worked out his sociology of domination. He differentiates between power and domination . He defines power as "the chance to enforce one's own will within a social relationship even against resistance, regardless of what this chance is based on", and domination as "the chance to find obedience to a given person for a command of certain content".

Weber's sociology of domination became famous primarily for the construction principle of the ground of validity, that is, the existence of a legitimate order. With his rulership typology, he differentiates between three pure (ideal) types: traditional , charismatic and legal rule. They differ according to two criteria: 1. Basis of legitimacy and 2. Type of administrative staff. Legal rule is based on belief in the legality of established orders; the administrative staff is formed by the bureaucracy with its officials. Traditional rule is based on the belief in the sanctity of traditional traditions; their administrative staff consists of the servants. The charismatic rule is based on the "extraordinary devotion to the holiness or the heroic power or the commitment of a person and the orders revealed or created by them"; the followers are to be regarded as their administrative staff.

Weber's state-sociological considerations are mostly treated as part of the sociology of domination. He sees the state as a modern form of political rule. He distinguishes the sociological concept of action from the legal concept of the state. The lawyers understand him as an acting collective personality, he as a sociologist understands by it “a certain kind of process of actual or as possible constructed social action of individuals”. Weber's centering of the monopoly of violence on the state became a school for political science . In business and society , he defines: "State should be called a political establishment if and to the extent that its administrative staff successfully claim the monopoly of legitimate physical coercion to carry out the regulations." The demand nevertheless had consequences for the law, because Weber's formulated obsessional theory , he created a legal concept . Using the terminology - developed for industrial mass societies - the monopoly on force and its enforcement by state forces could be combined, as long as the state was a generally recognized authority in society. He sees the bureaucracy as the nucleus of the state, on which the modern large state "is technically [...] absolutely dependent".

The bureaucracy is of central importance in Weber's work. For him, as Talcott Parsons said, it plays the same role as the class struggle for Karl Marx. Every rule expresses itself as an administrative apparatus. As the most rational means of rule, bureaucratic administration is also the characteristic form of administration of legal rule. In bureaucratisation, he recognizes “ the specific means of converting 'community action' into rationally ordered 'social action'.” However, it harbors the risk of becoming independent: rule by means of a bureaucratic administrative staff can turn into domination by the administrative staff. Their technical efficiency turns them into a juggernaut, which in the modern state institution as in the capitalist enterprise creates a pull of their "inescapability" and "unbreakability", through which they ultimately - in the much-quoted formulation - become the "steel-hard housing of bondage".

Sociology of Inequality (Classes and Estates)

In the first part of the originally compiled version of Economy and Society, Hans-Peter Müller opens up the last and shortest (considered to be incomplete) chapter “ Estates and classes ” as “varieties of social inequality” . In social inequality research, there were only two major approaches to class theory: that of Marx and Weber. Despite some similarities with Marx's, Weber uses a “pluralistic class concept”. Accordingly, he differentiates between “classes of property” and “classes of acquisition”: according to the type of property that can be used for acquisition on the one hand, and the services to be offered on the market on the other. He divides the “positively privileged” class members into “ pensioners ” and “ entrepreneurs ”. Between them and the "negatively privileged" classes, he places the "middle class" (for example, independent farmers and craftsmen), who play a "buffer role" and thereby dampen the conflicting social dynamics (from revolution to reform). Not only does he avoid Marx's “antagonistic class division” between capitalists and proletariat, he also questions his assumption that a common class situation leads to common class action. Classes are normally not communities, in contrast to classes, which do not result from the market situation, but from “social estimation” and the specific, birth or professional “lifestyle”. Classes belonged to the economic order or the sphere of production, classes to the social order and the sphere of consumption.

Legal sociology

Weber consistently dealt with the changeful relationship between law and social order. With their “excessive abundance of material” and their “mixture of generalizations and historical concretisms”, his legal texts have left well-known lawyers (such as Jean Carbonnier and Anthony T. Kronman ) very irritated.

Weber differentiates between legal science in the normative sense and empirical legal sociology. According to him, a “sociologization of jurisprudence ” is doomed to failure because of the “logical hiatus of being and ought”. The editors of the legal sub-volume emphasize in their epilogue that Weber carried out “the highly selective sorting of the infinite legal material” for the question of the rational foundations of modern law in the Occident. He speaks of theoretical rationality stages in the development of the law "from the charismatic legal revelation through legal prophet to the empirical law of creation and administration of justice through law dignitaries [...] to the law imposition by worldly empire and theocratic powers and finally to the systematic legal statutes and professional moderate, due to literary and formal-logical training in the 'administration of justice' carried out by legally educated (specialist lawyers ) ”. As an example, he works out the relative independence of legal technology compared to the political structures of rule by comparing Anglo-Saxon and continental law. He sees elective affinities of capitalism both with common law and with continental legal culture . The predictability of law, which serves capitalism, is guaranteed in England by judges recruited from the legal profession. The " case law " geared to practical needs is also more adaptable than a "systematic law subject to logical needs".

For Weber, law consists of compulsorily guaranteed norms that are enforced by an enforcement team. It is not tied to the “political association”, the state, but can appear in numerous “legal communities” of the “institutional socialization” (for example, township, church) before the state appears.

History and Sociology of the City

About the treatise Die Stadt , published posthumously in the Archive for Social Science and Social Policy in 1921 . A sociological investigation cannot be said with certainty as to the context Weber intended it for, as the editor of the corresponding partial volume of the complete edition notes. In the edition of Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft edited by Johannes Winckelmann , it was published under the title The non-legitimate rule (typology of cities) as a subchapter of the sociology of rule (Chapter 9, Section 7). The treatise consists of four parts: I. Concept and categories of the city, II. The city of the Occident, III. The family city in the Middle Ages and in antiquity , IV. The plebeian city . The chapter on the bourgeoisie in Weber's economic history. According to Hinnerk Bruhns, the outline of universal social and economic history reads like a compact summary. The focus of content is the emergence of the “modern working class”. With regard to the ubiquity of the city phenomenon, a comparison with cities in the Orient ( Egypt , Middle East , China , Japan , India ) shows that a self-governing middle class has only developed in the Occident. For an intra-occidental comparison Weber uses Italian cities as well as English and those on the other side of the Alps. A comparison of time between antiquity and the Middle Ages shows that the essential prerequisites for the emergence of modern capitalism were not created until the Middle Ages.

Organizational sociology

Most textbooks on organizational sociology treat Max Weber as one of their founding fathers. According to Renate Mayntz, this is due to misunderstandings of the American reception of his ideal type of bureaucracy, Veronika Tacke calls it a “productive misunderstanding”. The concept of organization in the modern sense, as an educational type, is hardly to be found in Weber's work; he usually speaks of organization in the sense of “organizing” (for example “organization of production and sales”). The term used by him of the association comes close to the modern term of organization without being congruent with it. For Weber, bureaucracy is the most formally rational form of exercise of power because it is “technically superior” to all other forms of administration in terms of its consistency, precision, rigor and reliability. The critical reception misunderstood Weber's ideal-typical method as “a kind of normative concept of organizational design” and referred to bureaucratic dysfunctions and non-rational deviations.

Work and industrial sociological studies

Along with Marx, Weber is one of the early authors of studies in the sociology of work . His first work in this regard is entitled The Situation of Farm Workers in East Elbe Germany (1892). It appeared as part of a farm workers' survey organized by the Verein für Socialpolitik for the entire German Reich . His habilitation thesis on Roman agricultural history, with which he had worked out the historical basis for the agrarian constitution, had identified him for this task. Weber noted the dissolution of the traditionally patriarchal labor constitution into a capitalist one and thus a “proletarianization of the agricultural workers” as a secular development trend. The relationship between landlord and worker tended to change from a personal relationship of domination , which was based on a traditional community of interests, to an objectified class relationship that reduced exchange to monetary payments. The investigation forms a largely underestimated basis for Weber's later work, because it contains many of his terms and concepts, such as ideal type, rule typology and capitalist entrepreneurship , in their first form.

Weber wrote the later study on the psychophysics of industrial work (1908/09) in connection with the survey initiated by the Verein für Socialpolitik on the selection and adaptation of the workforce in large-scale industry , for which Weber had also been asked for a methodological introduction, which would match the Survey participating social researchers should serve as a guide. The Psychophysics contains the results of a Weber himself conducted empirical study in a family's operation of Westphalia textile industry. The productivity of the individual worker was one of his most important test variables. Therefore, he discussed and reviewed many factors that could influence work performance, including: wages, humidity and noise in the work environment, alcohol consumption, sexual activity, regional origin, religious denomination, union membership, performance restrictions ("brakes"). The industrial sociologist Gert Schmidt evaluates this work and the methodological introduction as documents of Weber's importance as a forerunner and co-founder of industrial and company sociology . As a supplementary and partially expanding study of Weber's understanding of capitalism, he still finds it worth reading today.

Religious sociological works

Weber devoted a considerable part of his scientific work to religions; The three volumes of collected essays on the sociology of religion (1920–1921), on which he was still working in the year of his death and for which he wrote his famous preliminary remark , a “systematic sketch of his entire research program” (Hans-Peter Müller), bear witness to this . According to the religious scholar Hans G. Kippenberg , Weber uses a “relational concept of religion”; accordingly religion lives from the agreement or the difference with the other powers of order. Weber achieved a resounding success with his research into the cultural significance of Protestantism.

Protestantism and Capitalism

The core of Weber's analysis ( The Protestant Ethics and the 'Spirit' of Capitalism , 1904/05; revised 1920) is his evidence that there is an increased likelihood of the emergence of modern, “bourgeois working capitalism ” when certain economic components are combined with a religiously "founded", inner-worldly ascetic professional ethos come together. Weber does not claim that capitalist economic activity can be directly derived from Protestant origins of mentality.

The special "elective affinity" between Protestantism and capitalism is conveyed through the idea of professional ethics. Weber states that "through the cultural languages [...] the predominantly Catholic peoples for what we call 'occupation' (in the sense of position in life, limited field of work) know just as little an expression of a similar color as classical antiquity, while everyone does predominantly Protestant peoples exists ”. A “principle and systematic unbroken unity of inner-worldly professional ethics and religious certainty of salvation has only brought about the professional ethics of ascetic Protestantism throughout the world. [...] The rational, sober, purposeful character of action that is not given to the world and its success is the characteristic that God's blessing rests on it. ”The development of“ professional humanity ”as one component of the“ capitalist spirit ”among several was According to Weber, due to individual religious motifs that were highly effective in the 17th, 18th and also in the 19th century - occupation as a "calling" and the resulting ethos of "rational", inner-worldly, ascetic lifestyle. In Calvinism, which was shaped by the doctrine of predestination , as well as in other Protestant movements, Methodism , Quakerism and Anabaptist sectarian Protestantism , as well as in part also in Pietism , Weber found a version of the motif of probation that he found for the emergence of a methodology that structured the whole of life blames.

In view of the uncertainty about one's own religious status, the thought of the necessity of permanent and consistent probation in life and especially in professional life became the most important reference point for one's own destiny for bliss. As Weber has repeatedly emphasized against various misunderstandings, it is not a "real reason", but a "knowledge reason", i.e. a purely subjective guarantee of the certainty of salvation. The believer does not earn his “bliss” by observing his professional duty (and the resulting success), but rather by securing it for himself through it. According to Weber, the resulting concept of a rational way of life is an essential factor in the history of the development of modern Western capitalism, and of Western culture in general.

Weber also emphasized the limited scope of his discussions several times. He described as a “foolish doctrinal thesis” that “the 'capitalist spirit' […] could only have emerged as the outflow of certain influences of the Reformation or even: that capitalism as an economic system was a product of the Reformation”. To the insinuation that he wanted to formulate a consistently “idealistic” counterposition to Marxist materialism , he replied: “[...] so it can of course not be the intention to replace a one-sided 'materialistic' with an equally one-sided spiritualistic causal culture and culture Set history interpretation. Both are equally possible, but with both, if they claim to be the conclusion of the investigation rather than preliminary work, the historical truth is equally ineffective. "

The connection pointed out by Weber is the subject of an extremely intense discussion. It is probably the most widely discussed individual academic achievement in the field of sociology, history and cultural studies. Methodological, factual-historical and biographical-contemporary approaches can be distinguished. Some critics accuse Weber of having formulated his thesis in such a way that it was methodologically "irrefutable". Extensive research literature is devoted to the empirical verification of Weber's findings and the conclusions drawn from them. But Weber's text is also interpreted and problematized as an expression of self-image, as existed in the German bourgeoisie around 1900.

Beyond the criticism in detail, the extraordinary scientific rank of the text is undisputed: Weber's analysis of the mentality (or religious) historical character of modernity offers a substantially well-founded framework for understanding essential aspects of the political, economic and cultural present ("rationalization", " Bureaucratization ", mass society among others). For many sociological, cultural studies, theological history or philosophical approaches of the latest time (e.g. for Habermas ' theory of communicative action ) Weber's “Protestantism-capitalism thesis” and the associated theory of the rationalization process form an important point of reference.

The business ethics of the world religions

Weber later expanded his religious sociology considerably. Under the heading The Business Ethics of World Religions , the first volume of the collected essays on the sociology of religion already contained the chapter on Confucianism and Taoism , the second volume then Hinduism and Buddhism and finally the third volume Ancient Judaism. Addendum. The Pharisees . The study of Protestant ethics , which is exemplary for the special development in the Occident , is systematically compared in these essays with other world religions and regions. In them, too, he addressed not only the influence of religious ideas on non-religious activity, but also the opposite influence. In summary, Weber comes to the conclusion that the Asian religions influenced a way of life that "made a development towards capitalism impossible".

Types of religious communalization

In the chapter on the sociology of religion (types of religious communalization) in the economy and society (1921/22) Weber systematically dealt with the attitudes of religions towards the “world”. The system of religions partially overlaps in content with the introduction to the economic ethics of the world religions , but the former is a “complex, compressed, abstract and elaborate conceptual classification of Weber's approach to the sociology of religion”. Here, too, his résumé is that no path from the Asian religions led to a “rational method of living”, especially no development to a “capitalist spirit” such as was appropriate for ascetic Protestantism ”. Axel Michaels assessed Weber's expansion of his research on the sociology of religion primarily from the endeavor to substantiate his original thesis: “India, China, Israel and the Middle East were for him the experiment that was supposed to prove his Protestant thesis, but it was not the beginning the preoccupation with the world religions from which this theory grew. "

Music sociology

The music-sociological work The rational and sociological foundations of music comes from Weber's later work phase . Probably written in a period from 1910 onwards, it was first published as an independent publication in 1921 as an unfinished work from the estate. It was written in a work phase when Weber was intensely interested in a “sociology of culture content”. During these years he had long conversations with the young Georg Lukács about the redeeming power of art. His intimate friendship with the pianist Mina Tobler also made him biographically sensitive to the music .

What was remarkable and exciting for Weber was the discovery that even music was part of the Occidental rationalization process, which led him to the conclusion that "rational harmonic music, like bourgeois working capitalism [...] only produced occidental culture". Meanwhile, Walther Müller-Jentsch and Dirk Kaesler suspect that these are different concepts of rationality. Steffen Sigmund evaluates the font as the "founding document of (German) music sociology", For Theodor W. Adorno it is "the most comprehensive and demanding draft of a music sociology to date".

reception

The international Weber reception is barely manageable. It started shortly after his death. 1923 by the Hungarian-born appeared Melchior Palyi issued remembrance gift for Max Weber . Marianne Weber published her first detailed biography in 1926. By Alexander von Schelting the most important work on Weber appeared Wissenschaftslehre before the Second World War. Together with Karl Löwith , he set emphasis on Weber's academic style of thinking in the archive for social science and social policy . Promoted by the emigrated German social scientists, an almost continuous international reception developed.

After the Second World War , Max Weber did not lose importance as a sociologist, unlike Ferdinand Tönnies and Werner Sombart . His works continue great deal of attention, although in the early post-war years in Germany in the focus of social science research first studies on the leveled middle-class society Schelsky , the conflict theories of Dahrendorf and the group experiment of the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research were. At that time Weber was one of the few who, besides Martin Heidegger, most famous philosopher Karl Jaspers , who for most of his life was Weber as a scholar and researcher , referred explicitly to Weber ; he had been under his influence since 1909 and his philosophizing had "not happened all these years without thinking of Max Weber". In the manuscript of a lecture he gave on “Philosophy of the Present” in the winter semester 1960/61, he referred to Weber, together with Albert Einstein, as the most important contemporary philosophers. As a budding philosopher of high standing, Dieter Henrich postulated the unity of Max Weber's science teaching as early as 1952 with the title of his dissertation . The first comprehensive work biography of the emigrant Reinhard Bendix was published in the USA in 1960, focusing on sociology, which was translated into German in 1964. In his foreword, René König , like Jaspers, referred to Weber as both a philosopher and a politician and sociologist.

A new subject-specific occupation with Weber's work began in Germany with the Heidelberg Sociologists' Day in 1964, at which the German sociologists on Weber's 100th birthday presented the status of international weavers through Talcott Parsons, Herbert Marcuse , Reinhard Bendix , Raymond Aron , Ernst Topitsch and Pietro Rossi -Reception was shown. After that, the secondary literature on Weber's work and significance grew continuously. Mainly Friedrich Tenbruck and Johannes Weiß contributed to the reception of Weber's sociological work in the 1970s. The Max Weber Lectures organized by Heidelberg University since 1981 were opened with Reinhard Bendix's guest professorship.

The Max Weber Complete Edition has been published by the Commission for Social and Economic History of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences since 1984 . It comprises a total of 47 volumes in three sections (I. Writings and speeches, 24 volumes and 5 sub-volumes; II. Letters, 11 volumes; III. Lectures and lecture transcripts, 7 volumes). The eminent editorial work was completed on the 100th anniversary of his death. Two of its editors, M. Rainer Lepsius and Wolfgang Schluchter , became fixed points for the German reception early on in a constant examination of Weber's work.

The topicality of Weber's work is evident in its connectivity to the entire cultural and social sciences. The most important sociological textbook applies worldwide economy and society ( Economy and Society ). In the political science reception of Weber it is listed as a classic of political thought. The definition of the state as the “monopoly of legitimate physical violence”, which was formulated in his lecture on politics as a profession and , according to the political scientist Andreas Anter , has been “the most powerful of the last hundred years”, contributed in particular to this . In the historical sciences, Weber's conception of “universal history” was primarily received, whereby, according to Wolfgang Mommsen, Weber's question about the driving forces of social change was by no means limited to a social history of the Occident. Eric Hobsbawm traces back a consciously “Weberian school of historiography as differentiated from a Marxist one” to the social historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler . In the Marxist reception, the complementarity of Weber's capitalism analyzes is emphasized: With the importance of religious ideas for the emergence of capitalism, Weber explored the “subjective side” of historical development without denying the “materialistic”. He also corrected the subordinate role of culture in the historical process in (dogmatic) Marxist thinking. George Lichtheim emphasized that "the entire content of Weber's sociology of religion fits into the Marxist scheme without difficulty." Criticism, however, was his conception of the nation state, to which he assigned an independent (and partly imperial) role, and his voluntarist concept of charisma. As a Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm considers Weber's necessary addition to and correction of Marx's "political and ideological stance" to be unacceptable, despite the high esteem of Weber.

In the USA, the dissemination of Weber's ideas was largely driven by the structural functionalism of Talcott Parsons, which prevailed in sociology after 1945, and his translations of Weber's works, Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism as well as Economy and Society, into English. Weber's work on the importance of Protestant ethics for the development of modern capitalism, in particular, was discussed very often and controversially there, but also in Germany. Weber's analysis of modern bureaucracy, especially his type of “legal rule with a bureaucratic administrative staff” as the formally most rational form of rule, was used by American organizational sociologists in their analyzes of the administration of state and economic organizations. For the organizational theorist Alfred Kieser , Weber's analyzes of bureaucracy made him a “pioneer of modern organizational theory”. Although Weber was not a genuine organizational researcher, his bureaucracy model "had its enormous impact mainly in organizational research and still has it there". Weber's bureaucratic approach has been part of the canon of organizational sociology textbooks alongside Taylor's and Fayol's management teachings for decades . Organizational research owes important advances in knowledge to the gradual dismantling of its “machine model” of the bureaucratic organization.

The Japanese Weber reception went different ways than the western one. Japanese social scientists became aware of him during Weber's lifetime. They owe an extraordinarily extensive secondary literature with a thematic range that covered all of Weber's material research areas. Arnold Zingerle traces the intense reception back to a supposed affinity of Weber's questions with the intellectual and cultural situation in Japan, as interpreted by his social scientists. Weber's work contributed to understanding the Japanese modernization process and Japanese capitalism.