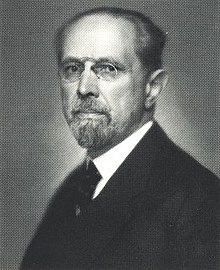

Werner Sombart

Werner Sombart (born January 19, 1863 in Ermsleben , † May 18, 1941 in Berlin ) was a German sociologist and economist .

Life

Werner Sombart was the son of the manor, industrialist and national liberal politician and Reichstag member Anton Ludwig Sombart . With his first wife he had four daughters, including Clara, who was married to the discoverer of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease , Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt . In his second marriage, Sombart was married to Corina Leon (September 9, 1892 - February 19, 1970), the 30 years younger daughter of a Romanian university professor. The cultural sociologist Nicolaus Sombart and the painter Ninetta Sombart came from this marriage .

After attending grammar school, Sombart studied law from 1882 to 1885 at the universities in Pisa (including with Giuseppe Toniolo ), Berlin and Rome , and also attended political and economic, historical and philosophical lectures. He drew socialist impulses from Gustav Schmoller and Adolph Wagner . In 1888 he received his doctorate from Schmoller in Berlin with a thesis on the economy of the Roman Campagna ( The Roman Campagna ). In 1888 he became in-house counsel at the Bremen Chamber of Commerce , and in 1890 professor of political science. Appointments to Freiburg, Heidelberg and Karlsruhe failed because of the objection of the Grand Duke Friedrich II of Baden, who rejected him as a radical left.

Sombart became a professor at the University of Breslau in 1890 , where he taught political science until 1906. He specialized in European economic history. In 1906 he followed a call to the Berlin School of Management. From 1918 he taught at the Friedrich Wilhelms University in Berlin . In 1931 he retired there, but continued to teach until 1938. Emil Lederer was the successor to his chair . In Berlin he had Ernst Oppler portray himself .

Sombart was a member of the National Socialist Academy for German Law, founded in 1933 . In the same year he was accepted as a full member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and as a corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . On August 19, 1934 he was one of the signatories of the appeal for German scientists behind Adolf Hitler to vote on the head of state of the German Reich , which appeared in the Völkischer Beobachter .

Sombart was the last chairman of the Verein für Socialpolitik until its self-dissolution in 1936 (it was re-established in 1948).

His grave can be found in the Dahlem forest cemetery in Berlin . The grave is one of the honor graves of the State of Berlin .

Act

Sombart's work Socialism and Social Movement in the 19th Century from 1896 strengthened his reputation as a socialist through his positive reception of Marx . In his main work, Modern Capitalism (1902), he established the division into the development phases early , high and late capitalism . Like his contemporary Max Weber , Sombart was concerned with a specifically sociological and historical foundation of the development history of the capitalist system .

Sombart's sociology claimed, among other things, a correspondence between spirit and society , which means that the humanities and social sciences must be seen as a unit. Noteworthy are his contributions to the importance of luxury . After Sombart initially had a positive view of Karl Marx's theses, in later years he took a national- conservative stand as a pessimistic cultural philosopher . Some historians consider Sombart to be a socially conservative pioneer of National Socialism .

In the book Die Juden und das Wirtschaftsleben (The Jews and Economic Life), Sombart made a connection that made the Jews seem as if they were made as main capitalist actors. As a wandering people, they would never have developed a bond with the ground, but instead developed all the more intensely to the abstract value of money, developed primarily rational relationships and thus acquired an ability to capitalism that a settled people could never have developed. He describes the contrast between a nomadic Jewish "desert people" and a Nordic "forest people", to whom he assigned the fundamentally conflicting world views of "Saharism and Silvanism". Furthermore, Sombart presented the business method of “catching customers” as unchristian and thus “Jewish”. In the 13th chapter of this book he deals with “the racial problem ” with the keywords “the anthropological peculiarity of the Jews”, “the Jewish 'race'”, “ the constancy of the Jewish being "," the racial justification of folk idiosyncrasies ". Although he is using common prejudices of his time on a highly fragmentary and flawed basis of evidence, he claims to have proceeded “strictly scientifically” in his book. For the scientist Friedemann Schmoll , Sombart thus built a bridge to open anti - Semitic anti - capitalism . This interpretation favored Sombart's career under National Socialism. However, the contemporary reception of the book was inconsistent. Some Jewish and anti-Semitic critics even considered the work to be philo-Semitic. In the press, Die Juden und die Wirtschaftsleben sparked a fundamental debate about the “Jewish question” and about the status and prospects of assimilation. Sombart himself also made a significant contribution to the discussion with a lecture tour and the anthology, Judentaufen (1912), which was compiled together with Arthur Landsberger . He pleaded for a national Jewish "species conservation" on the basis of a racist multiculturalism . However, the Jews should not emigrate, but rather form an ethnic minority separated from the majority population. This position earned Sombart applause from the Zionists and criticism from those who favored assimilation.

In Traders and Heroes of 1915, Sombart expanded this racism to include England , who was the enemy of the war at the time . For him, the British are a despicable “merchant people” with a soulless merchant spirit and greed for profit that can be valued low; the Germans, on the other hand, are heroes, called to great deeds and ideas. This idea of Sombart was enthusiastically received by Thomas Mann in the considerations of an apolitical person ; he ascribed to the Anglo-Saxons precisely these negative attributes which the anti-Semites had previously reserved for the Jews; Mann's expansion of this idea from the British to all Anglo-Saxons is due to his enthusiasm for the sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania by the Imperial Navy under Alfred von Tirpitz .

In The Bourgeois , Luxury and Capitalism and War and Capitalism , he continued to deal with the causes of the rise of capitalism.

In Proletarian Socialism , a new edition of socialism and social movement , Sombart's transformation into a supporter of the Conservative Revolution is indicated. His attempts to gain political influence and effectiveness in the National Socialist regime failed when he was attacked. This also alienated Sombart from National Socialism. The book German Socialism was rejected as incompatible with the National Socialist worldview, although he admitted himself in the preface to the “Hitler government”, called for the disenfranchisement of the Jews and argued “from the standpoint of a National Socialist conviction”. Students were advised not to attend his lectures. In his work Vom Menschen , written in 1938, he clearly distances himself from National Socialist racial theories .

reception

In 1946, what is socialism? Was published in 1935 in Sombart's Soviet zone . included in the list of literature to be discarded .

After Sombart was almost forgotten in the English-speaking world, the translated and annotated editions of some of his writings by Reiner Grundmann and Nico Stehr have made him more accessible there.

He is the namesake of Werner Sombart-Straße in Konstanz, which is under discussion of renaming in 2020.

Memberships (selection)

Works

- (1896): Socialism and Social Movement in the 19th Century. Fischer, Jena. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8481 )

- (1901): Technology and Economy. Zahn & Jaensch, Dresden. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8447 )

- (1902): Economy and fashion. A contribution to the theory of modern demand design. Bergmann, Wiesbaden. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8464 )

- (1902/1927): Modern Capitalism. 3 volumes. Duncker and Humblot, Leipzig.

- Vol. 1. The genesis of capitalism. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8042 )

- Vol. 2. The theory of capitalist development. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8050 )

- Vol. 3.1. Economic life in the age of high capitalism. The basics. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8073 )

- Vol. 3.2. Economic life in the age of high capitalism. The course of the high capitalist economy. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8087 )

- (1903): The German National Economy in the 19th Century. Berlin (digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8451 ) 5th edition, 1921 - Internet Archive

- (1906): The proletariat. Pictures and Studies. "The Society" series, vol. 1., Rütten & Loening, Berlin.

- (1906): Why is there no socialism in the United States? Mohr, Tuebingen. ( archive.org )

- (1911): The Jews and Economic Life. Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig ( archive.org ).

- (1913): Studies on the history of the development of modern capitalism. Duncker & Humblot, Munich / Leipzig.

- Vol. 1. Luxury and Capitalism. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8161 )

- Vol. 2. War and Capitalism. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8181 )

- (1913): The Bourgeois. On the intellectual history of the modern business man. Duncker & Humblot, Munich / Leipzig (digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8035 )

- (1915): Merchants and Heroes. Patriotic reflections. Duncker & Humblot, Munich / Leipzig.

- (1924): Proletarian Socialism ('Marxism'). 2 volumes.

- (1925): The order of economic life. Duncker & Humblot, Munich / Leipzig; Reprint of the 2nd edition from 1927 by Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg / Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-540-72255-7 .

- (1930): The three economies. History and system doctrine of the economy. Duncker & Humblot, Munich / Leipzig. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8396 )

- (1934): German Socialism. Buchholz & Weisswange, Berlin-Charlottenburg. ( Digitized version )

- (1935): What is German? Berlin-Charlottenburg.

- (1938): About humans. Attempt at a humanities anthropology. Berlin-Charlottenburg. (Digitized edition at: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8479 )

- (1956): Noo-Sociology. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin.

- (2002): Political Economy as Theory of Capitalism. Selected Writings. Metropolis Verlag, Marburg, ISBN 3-89518-407-1 .

- (2008): The Proletariat. Metropolis Verlag, Marburg. New edition of the title published in 1906, commented on by Friedhelm Hengsbach SJ. ISBN 978-3-89518-650-9 .

- (2012): Modern Capitalism. Historical-systematic presentation of pan-European economic life from its beginnings to the present. 3 vols. Salzwasser, Paderborn 2012 ISBN 978-3-86383-076-2 , ISBN 978-3-86383-077-9 , ISBN 978-3-86383-078-6 .

Cooperation

- (1912): Arthur Landsberger (Ed.): Judentaufen. Georg Müller Verlag, Munich.

- (1919): Friedrich Ramhorst (ed.): Foundations and criticism of socialism. Series: Anthology of Sciences. 2 volumes. Askanischer Verlag, Berlin. ( Volume , Volume 2 - Internet Archive )

Letters

- Martin Tielke (ed.): Schmitt and Sombart. Carl Schmitt's correspondence with Nicolaus, Corina and Werner Sombart. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-428-14706-9 .

- Thomas Kroll, Friedrich Lenger, Michael Schellenberger (Eds.): Werner Sombart. Letters from an Intellectual 1886-1937. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-428-15541-5 . ( Review )

See also

literature

- Michael Appel: Werner Sombart. Historian and theorist of modern capitalism. Metropolis-Verlag, Marburg 1992, ISBN 3-926570-49-0 .

- Jürgen G. Backhaus (Ed.): Werner Sombart (1863-1941). Social scientist. 3 vol. Marburg 1996 (standard work on current Sombart research).

- Jürgen G. Backhaus (Ed.): Werner Sombart (1863-1941). Classics of the social sciences. A critical inventory. Metropolis-Verlag, Marburg 2000, ISBN 3-89518-275-3 .

- Avraham Barkai : Judaism and Capitalism. Economic ideas from Max Weber and Werner Sombart. In: Menorah. Yearbook for German-Jewish History , Vol. 5. Piper, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-492-11917-4 , pp. 25-38.

- Bernhard vom Brocke (Ed.): Sombart's "Modern Capitalism". Materials for criticism and reception. Dtv , Munich 1987.

- Bernhard vom Brocke: Werner Sombart . In: Hans-Ulrich Wehler (Ed.): Deutsche Historiker , Volume 5, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1972, pp. 616–634.

- Konrad Fuchs: Sombart, Werner. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 10, Bautz, Herzberg 1995, ISBN 3-88309-062-X , Sp. 768-769.

- Thomas Gräfe: The Loss of Hegemony of Liberalism. The “Jewish question” as reflected in the intellectual surveys of 1885-1912 . In: Yearbook for Research on Antisemitism 25 (2016), pp. 73-100.

- Werner Krause: Werner Sombart's path from cathedral socialism to fascism , Rütten & Löning, Berlin 1962, bibliography pp. 185–191. .

- Friedrich Lenger : Werner Sombart 1863–1941. A biography. Beck, Munich 1994 (standard work; the subject of a discussion in Die Zeit , see Wolfgang Drechsler , in: Backhaus, 2000).

- Friedrich Lenger: Social science around 1900. Studies on Werner Sombart and some of his contemporaries. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-59408-7 .

- Friedrich Lenger: Sombart, Werner. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , p. 562 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Frederick Louis Nussbaum: A History of the Economic Institutions of Modern Europe. An Introduction of 'Modern Capitalism' by Werner Sombart. Crofts, New York 1933.

- Nicolaus Sombart : Youth in Berlin, 1933–1943. A report. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1991.

- Rolf Peter Sieferle : The resigned anti-capitalism: Werner Sombart . In: ders .: The Conservative Revolution. Five biographical sketches. (Paul Lensch, Werner Sombart, Oswald Spengler, Ernst Jünger, Hans Freyer) Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt 1995, ISBN 3-596-12817-X .

- Torsten Meyer : Werner Sombart (1863-1941) . In: Technikgeschichte 76 (2009), no. 4, pp. 333–338.

Web links

- Literature by and about Werner Sombart in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Werner Sombart in the German Digital Library

- Entry on Wikibooks

- Friedrich Lenger: Werner Sombart . In: East German Biography (Kulturportal West-Ost)

- Newspaper article about Werner Sombart in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Individual evidence

- ^ Ernst Klee : The dictionary of persons on the Third Reich . Who was what before and after 1945? 2nd Edition. Fischer TB, Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 978-3-596-16048-8 , p. 587.

- ^ Members of the previous academies. Werner Sombart. Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities , accessed on June 17, 2015 .

- ^ Ernst Klee: The dictionary of persons on the Third Reich . Fischer TB, Frankfurt 2005, p. 587.

- ^ Ferdinand Knauß: The fairy tale of the immigrant growth driver . In: Wirtschaftswoche , February 8, 2016

- ^ Ernst Klee: The dictionary of persons on the Third Reich. Fischer Verlag, 2005, p. 586. See Bernhard vom Brocke: Werner Sombart. In: Hans-Ulrich Wehler (ed.): German historians. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1972, p. 144.

- ↑ a b c Irene Raehlmann: Ergonomics in National Socialism: An analysis of the sociology of science. VS Verlag, 2005, p. 157.

- ↑ a b c d Friedemann Schmoll: The defense of organic orders: nature conservation and anti-Semitism between the German Empire and National Socialism. In: Joachim Radkau, Frank Uekötter: Nature conservation and National Socialism. Campus Verlag, 2003, p. 176.

- ↑ Werner Sombart: The Jews and the economic life. Duncker & Humblot Munich / Leipzig 1913 [first 1911], p. 426 and p. 476

- ↑ The Jews and Economic Life. Berlin 1911, p. 337 ff.

- ↑ Werner Sombart: Baptism of Jews. Munich 1912, pp. 7-20.

- ↑ Willi Jasper: Der Furor teutonicus. In: Welt am Sonntag . March 1, 2015, referring to his book Lusitania. Cultural history of a catastrophe. 2015.

- ^ List of literature to be sorted out 1946 .

- ^ Book Review: Sombart, Economic Life in the Modern Age . Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ↑ Citizens' hearing on street renaming. Website of the city of Konstanz, June 23, 2020.

- ^ Reprint 2008, Die Gesellschaft series . NF 1, pp. 1-90.

- ↑ Love, Luxury and Capitalism. 2nd Edition. Wagenbach Taschenbuch Nr. 103, Berlin 1967. Love created capitalism. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung , July 31, 2011, p. 26, also Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1967.

- ↑ Reproduction rororo, German Encyclopedia No. 473.

- ^ 10th edition of socialism and social movement in the 19th century.

- ^ Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-428-12083-3

- ↑ Review

- ↑ The German National Library lists the work only under the series title

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sombart, Werner |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German sociologist and economist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 19, 1863 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Experience |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 18, 1941 |

| Place of death | Berlin |