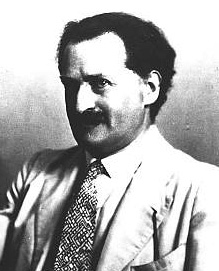

Emil Lederer

Emil Lederer (born July 22, 1882 in Pilsen , Austria-Hungary , † May 29, 1939 in New York ) was a Bohemian-Austrian economist and sociologist . He is considered an important German-speaking social scientist in the first half of the 20th century.

Life

Lederer was born in 1882 as the son of a businessman . He studied with other fellow students, such as Ludwig von Mises , Josef Schumpeter , Felix Somary , Otto Bauer and Rudolf Hilferding , law and economics at the University of Vienna with renowned teachers such as Heinrich Lammasch , Theodor Inama von Sternegg , Franz von Juraschek , Carl Menger , Friedrich von Wieser , Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and Eugen von Philippovich . He received his doctorate in 1905 from the University of Vienna as Dr. iur. and in 1911 at the University of Munich with Lujo Brentano as Dr. rer. pole. The following year he completed his habilitation at the University of Heidelberg with The Private Employees in Modern Economic Development , the first comprehensive study of the working conditions and political attitudes of employees.

During the First World War, Lederer was the editor in charge of the Archives for Social Science and Social Policy , in which he also published his treatise on the sociology of the world war with the main thesis that the organizational model of the army is socially generalized during war.

In 1918 he was appointed associate professor at Heidelberg University, but remained in Austria until 1920. At the beginning of 1919 he became a member of the German Socialization Commission alongside Hilferding and Schumpeter . In 1920 he became associate professor for social policy at the University of Heidelberg, and in 1920 full professor for social policy at the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. In 1921 Lederer became the managing editor of the “Archives for Social Science and Social Policy”. From 1923 to 1925 he was visiting professor at the University of Tokyo . From 1923 to 1931 Lederer was, together with Alfred Weber , director of the Institute for Social and Political Sciences. In 1931 he followed Werner Sombart to the renowned German chair for economics and finance at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin. Because of his political orientation, he was preferred to Joseph Schumpeter .

Like almost all economists at the “ Heidelberg School ”, Lederer was also given leave of absence by the National Socialists on April 14, 1933 under the “ Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service ”. The “Commissioner of the Reich” wrote to Lederer: “On the basis of the law for the restoration of the professional civil service of April 7, 1933 (RGBl., P. 175 ff.), I feel compelled to remove you from your office with immediate effect until the final decision to take leave. This leave of absence also applies to any activity that you carry out in connection with your main office or in connection with your university position. Your salary will continue to be paid to you in the same way until further notice. ”In addition, the notice of discharge reveals that Lederer had been denounced by the university because he had been a member of the SPD since 1925 and was also“ non-Aryan ”.

Lederer first emigrated to Japan and then to the USA . In 1933, Lederer was one of the co-founders of the unique University in Exile at the New School for Social Research in New York City , later the Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science , as its first dean until his sudden death. He was a key advisor to Alvin Johnson in faculty recruitment ; With Arthur Feiler , Albert Salomon and Hans Speier , three of his former doctoral students were among the founding members. Emil Lederer died in 1939 as a result of an operation.

Lederer was editor of the SPD theory journal Die Neue Zeit .

Act

Lederer combined economics and sociology and was thus the most important representative of an interdisciplinary approach in the Heidelberg social sciences. He attached importance to the fact that sociology has the character of a basic science, since it is able to describe "human relationships as such", whereas economics is one of the "individual sciences" because it is based on a "certain point of view" proceed and therefore, if their findings were not interpreted sociologically, they would have to "cloud" the scientific concept formation.

In his sociological work, Lederer was on the one hand concerned with the further development of Max Weber's scientific theory ; on the other hand, he analyzed various contemporary phenomena in the sense of a cultural sociology that should be decidedly political, but without giving up its claim to scientific quality. B. the gain in importance of interest organizations in political life, the habitual effects of the changed work organization, the change in shape of violence in the capitalist age, the social situation of art, the cultural specifics of Asian capitalism or public opinion. Due to the passage of time, these investigations led to the great study on the genesis and shape of totalitarianism in Europe, which was published by his student Hans Speier only after Lederer's death .

Lederer's economic analyzes reflected a rich theoretical background that spanned from the holistic- empirical approach of the historical school to the theoretical tools of the Austrian school and beyond to David Ricardo and Karl Marx . For example, Lederer quoted Schumpeter, Knut Wicksell and Gustav Cassel in his 1925 article on business cycles ; in other works Albert Aftalion and John A. Hobson , Thorstein Veblen , Arthur Pigou , Wesley Mitchell , Irving Fisher and John M. Keynes . He examined the inefficiency of monopolies and saw planned economy instruments as a possible alternative. Lederer was more skeptical about the effects of technical progress than most other economists. To Nicholas Kaldor's harsh criticism responded Lederer with a revised version of its Technical progress and unemployment ( ILO , 1938), in which he sought to put his position clearly and expand.

Fonts (selection)

- On the sociology of the world war . In: Archive for Social Science and Social Policy 39 (1915), pp. 347–384.

- The changes in class structure during the war. 1918.

- The sociology of violence. In: Sociological Problems of the Present. Cassirer, Berlin 1921, pp. 16-29.

- Economy and crises. In: Grundriss der Sozialökonomik. Mohr, Tübingen 1925, pp. 354-413.

- Monopolies and the economy. In: Quarterly issues for economic research. Supplementary Volume 2, pp. 13–32.

- Outline of the economic theory. 3rd, exp. and completely redesigned. Ed., Mohr, Tübingen 1931.

- Technical progress and unemployment. Mohr, Tübingen 1931.

- Effects of wage cuts. A presentation. Mohr, Tübingen 1931.

- Planned economy. Mohr, Tübingen 1932.

- Technical progress and unemployment. ILO, Geneva 1938.

- State of the masses. The threat of the classless society. Norton, New York 1940; German edition under the title Der Massenstaat. Dangers of the classless society. Nausner and Nausner, Graz / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-901402-03-9 .

- Capitalism, class structure and problems of democracy in Germany 1910–1940. Selected essays. Edited by Jürgen Kocka , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1979 (= Critical Studies in History , Vol. 39).

- Writings on science and cultural sociology. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2014.

literature

- Emil Lederer. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 5, Publishing House of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1972, p. 82 f. (Direct links on p. 82 , p. 83 ).

- R. Richter, K. Zapotoczky: Lederer, Emil . In: Wilhelm Bernsdorf , Horst Knospe (ed.): Internationales Soziologenlexikon , vol. 1, Enke, 2nd edition, Stuttgart 1980, p. 238 f.

- Werner Röder, Herbert A. Strauss (Eds.): International Biographical Dictionary of Central European Emigrés 1933–1945 . Volume 2, 2. Saur, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-598-10089-2 , p. 699 f.

- Dirk Kaesler : Lederer, Emil. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , p. 40 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Claus-Dieter Krohn (ed.): Emil Lederer: The mass state. Dangers of the classless society. (= Library of Social Science Emigrants , Vol. II). Nausner & Nausner, Graz / Vienna 1995, ISBN 3-901402-03-9 .

- Elisabeth Allgoewer: Emil Lederer. Business cycles, crises, and growth . University of St. Gallen, October 2001. Discussion paper no. 2001–13.

- P. Michaelides, J. Milios and A. Vouldis: Schumpeter and Lederer on Economic Growth, Technology and Credit, European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy, Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference . Postage, November 1-3, 2007 (CD-ROM).

- P. Michaelides, J. Milios and A. Vouldis: Emil Lederer and the Schumpeter, Hilferding, Tugan-Baranowsky Nexus, Research Workshop in Political Economy, International Initiative for the Promotion of Political Economy . Organized by University of London and University of Crete, Rethymnon, September 14-16, 2007.

- P. Gostmann and A. Ivanova: Emil Lederer: Science teaching and cultural sociology . In: Emil Lederer. Writings on science and cultural sociology . Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2014, pp. 7–37.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Elizabeth Allgoewer: Emil Lederer. Business cycles, crises, and growth . University of St. Gallen, October 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Emil Lederer: On the sociology of the world war. In: Archive for Social Science and Social Policy 39 (1915), 3, pp. 347–384.

- ^ Fritz Köhler: On the expulsion of humanist scholars 1933/34 ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Emil Lederer: On the method controversy in sociology. In: Writings on science and cultural sociology . Springer VS, 2014, pp. 259–282, here p. 275.

- ↑ Peter Gostmann and Alexandra Ivanova: Emil Lederer: Wissenschaftslehre und Kultursoziologie. In: Emil Lederer: Writings on science and cultural sociology . Springer VS 2014, pp. 7–37.

- ^ Emil Lederer: The economic element and the political idea in modern party systems . In: Writings on science and cultural sociology . Springer VS, 2014, pp. 81–99.

- ^ Emil Lederer: On the socio-psychological habitus of the present . In: Writings on science and cultural sociology . Springer VS, 2014, pp. 195-216.

- ^ Emil Lederer: Sociology of violence . In: Writings on science and cultural sociology . Springer VS, 2014, pp. 217-226.

- ^ Emil Lederer: Time and Art . In: Writings on science and cultural sociology . Springer VS, 2014, pp. 227-234.

- ^ Emil Lederer and Emy Lederer-Seidler: Japan - Europe. Changes in the Far East . Frankfurter Societäts-Druckerei, 1929.

- ^ Emil Lederer: The public opinion . In: Writings on science and cultural sociology . Springer VS, 2014, pp. 333-340.

- ^ Emil Lederer: State of the masses. The threat of the classless society . Norton, New York 1940.

- ↑ Elizabeth Allgoewer: Emil Lederer. Business cycles, crises, and growth . University of St. Gallen, October 2001, p. 3.

- ↑ Elizabeth Allgoewer: Emil Lederer. Business cycles, crises, and growth . University of St. Gallen, October 2001, p. 8.

- ↑ Elizabeth Allgoewer: Emil Lederer. Business cycles, crises, and growth . University of St. Gallen, October 2001, p. 14 ff.

- ^ Nicholas Kaldor: A case against technical progress? In: Economica , 1932; see. Robert A. Dickler: Emil Lederer and the modern theory of economic growth . Epilogue to Emil Lederer: Technical progress and unemployment. An examination of the obstacles to economic growth. European Publishing House Frankfurt am Main 1981, pp. 287–294.

Web links

- Literature by and about Emil Lederer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Emil Lederer in the German Digital Library

- Emil Lederer's biography

- Emil Lederer: Contributions to the Critique of the Marxian System (PDF file; 2.06 MB)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lederer, Emil |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Bohemian-Austrian economist and sociologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 22, 1882 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Pilsen |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 29, 1939 |

| Place of death | New York City |