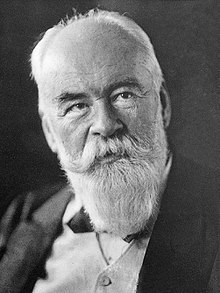

Gustav von Schmoller (economist)

Gustav Friedrich Schmoller , from 1908 by Schmoller (born June 24, 1838 in Heilbronn , † June 27, 1917 in Bad Harzburg ), was a German economist and social scientist . He is considered to be the main representative of the younger historical school of economics .

Life

Gustav Schmoller was born on June 24, 1838 in Heilbronn, where his father had been responsible for the Wuerttemberg fiscal interests since 1833 as camera administrator . The ancestors on the father's side came from Eisenach and Weimar ; one ancestor, Johannes Schmoller , was war secretary to Duke Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar during the Thirty Years' War and entered service in Württemberg in 1651; Oswald Schmoller was a pastor and was ordained by Martin Luther in 1538 . The origin on the mother's side leads to the patriciate of the old and important Württemberg industrial and trading town of Calw . The ancestors of the mother, Theresa Gärtner, were involved in the Calw armory trading company; in her family there are mainly doctors and scientists. The gardeners were first pharmacists, then doctors, naturalists and botanists in the following years . Gustav's great-grandfather Joseph Gärtner was one of the most respected botanists of his time. His grandfather Karl Friedrich von Gärtner had devoted his life to studying the variability of plant species and hybrids and was in correspondence with Charles Darwin , who quoted him several times in his work The Origin of Species .

Schmoller's early childhood was overshadowed by the death of two brothers (1841) and the death of his mother (1846). He himself was considered ailing and was sent to cure several times for fear of impending consumption . After pre-school and high school, he passed his Abitur in Stuttgart in 1856 as the third best in the whole country. He himself judged harshly about his school days. He thought it was thanks to two teachers that he didn't have to call his high school days lost. Because of his endangered health, the father kept him in his office for another year, where he became familiar with the practical application of financial and administrative law.

In the winter semester of 1857 Schmoller then began studying camera science at the University of Tübingen . The economists of the state university, Carl von Schütz and Johann von Helferich , did not leave a lasting impression on the young student. He was able to skip many lectures in finance, constitutional and administrative law without any problems due to his broad prior knowledge from his father's practice. In keeping with the now almost forgotten tasks of a university, Schmoller saw it as the aim of his endeavors to obtain the broadest possible, general scientific education and attended scientific, but above all philosophical and historical lectures.

The connection between economics and history emerged in Schmoller's first major written work. The investigation of economic views during the Reformation earned him a doctorate and was published in the Zeitschrift für die Allgemeine Staatswissenschaft in 1860. After passing the first state examination , the young financial trainee completed the first half of his legal clerkship again in his father's camera office in Heilbronn. At his own request, he performed the second half at the Württemberg Statistical Office, which his brother-in-law Gustav von Rümelin (fatherly friend and mentor) had taken over after his resignation from the Ministry of Education. With the publication The French Trade Route and His Opponents , published in 1862 . He took a word of understanding from a South German in favor of the recently concluded Prussian-French trade treaty that prevented Austria from joining the German Customs Union , and thus set himself in sharp contrast to the views of all southern German states sympathizing with Austria. This put an end to all hopes for a career as an official in Württemberg, but on the other hand earned him the applause of the Prussian Minister of Commerce, Rudolf von Delbrück , who from then on was to remain one of his patrons.

After two years of traveling reached Schmoller in the spring of 1864, the call to Halle, where he was the holder of a year later, the chair will succeed Johann Friedrich Gottfried Eiselen took. During this time, an article about the labor question falls, which Schmoller was able to publish in the Prussian yearbooks in 1864 and 1865. It already shows that two-front struggle that Schmoller was to lead over the next few years as a representative of a new socio-political direction: on the one hand against the Manchester liberals, on the other hand against the socialism of a Lassalle or Marx , whose revolutionary agitation was just as unsuitable for him seemed to improve the condition of the workers.

Schmoller then took over the office of city councilor in Halle in order to gain practical experience and soon met Lucie, the daughter of the Weimar Secret Council Bernhard Rathgen and granddaughter of Barthold Georg Niebuhr . A son, Ludwig von Schmoller (1872–1951), later an officer and father of Gustav von Schmoller , and a daughter, Cornelia (Nelly) von Schmoller (born September 30, 1879 in Strasbourg; † December 12th) came from the marriage in 1869 1932 in Cairo), who married the photographer Ernst Sandau in 1909 and, after the divorce in 1916, Pierre Schrumpf-Pierron .

In the second half of the 1860s Schmoller dealt intensively with the study of constitution, administration and economy of the Prussian state, where his main interest the reign of Frederick William I was. During this time his work “History of German Small Businesses in the 19th Century” (1870) was created. In this extensive document Schmoller described the small business "as a socio-politically necessary stability factor" and advocated "innovation promotion, cooperation and regulating self-government bodies".

The last guild barriers fell in Germany in the 1860s; The freedom of trade was anchored in the trade regulations of the North German Confederation in 1869 . Schmoller's reference to weak points in unrestricted freedom of trade brought him objections and attacks from the “Congress for Economists”, in which Manchester liberals and Smithians had come together at the time. Heinrich Bernhard Oppenheim coined the term “ Kathedersozialisten ” in order to brand Schmoller as a representative of anti-liberal state interventionism (1871). Criticism of the dark side of liberalism was often assessed as socialism by the liberals, even if this criticism did not come from the socialist camp.

The founding of the " Verein für Socialpolitik " in Eisenach in 1872 with Schmoller's significant participation, in whose house the preliminary talks with Adolph Wagner , Bruno Hildebrand and Johannes Conrad had taken place, was the consequence of this attitude. Schmoller was for many years chairman of the association, which still exists today (after an interruption in the years 1936–1948), through which he exerted a strong influence on economic policy (especially von Bismarck's). In the same year, Schmoller was appointed to the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelms University of Strasbourg . During this time, his work "The Strasbourg Cloth and Weavers Guild" was created.

Schmoller did not lose his connection to Prussia, spent part of the semester break in the Prussian archives in Berlin and became a regular contributor to the Prussian yearbooks. In his essays and lectures, the Kathedersozialist proved to be an incorruptible advocate of social justice. His socio-political demands earned him both rejection and approval: Heinrich von Treitschke (1875) saw in him a “patron of socialism”; Bismarck assured him during a visit to Strasbourg University in 1875 that he was himself a Catholic Socialist. For Schmoller it was clear that it was possible to raise the culture of the lower classes, that social progress, a fairer distribution could be achieved - even without a socialist revolution.

Schmoller could argue on an ethical and moral basis. Only a few, like Max Weber , demanded a solid theoretical justification for his statements. For a long time Schmoller had success with his idea of “cultural values”, but from the beginning of the 20th century he met with increasing criticism (→ value judgment dispute ). A rethinking of ethical-historical-philosophical foundations appeared to Schmoller and his followers, unlike his critics, to be completely sufficient for the establishment of values. Schmoller's call for an orderly and socio-politically active state, on the other hand, found more and more approval from specialist colleagues and politicians. These circumstances led to the fact that the "Yearbooks for Legislation, Administration and Economics in the German Reich" were transferred to him, which under his name as " Schmoller's Yearbook " were to become a central publication organ of German economics for decades. The fact that he was called to Berlin in 1882 can also be traced back to this change of opinion and the visible return of politics to the demands of the social reformers.

Here Schmoller published a number of large essays on Brandenburg-Prussian economic policy in the age of mercantilism . After the liberals' sharp rejection of mercantilism, he pointed to a number of examples in which mercantilist intervention politics seemed to work far more in the interests of social harmony than the politics of liberals.

In 1887 he was accepted as a full member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and brought out an edition of Acta Borussica, a large-scale collection of sources on the Prussian state and economic administration. At this time work began on a summarizing outline of economics. Publishers and journalistic competitors of his students urged to undertake such work. In 1900 the first volume, “Grundriß der Allgemeine Volkswirtschaftslehre”, appeared, which was immediately followed by several new editions. The second volume appeared in 1904. While he was still working on the work “Character Pictures” (1913), Schmoller decided to extensively revise his floor plan, which he was able to complete successfully.

In 1884 he became a member of the Prussian Council of State , after his rectorate in 1897/98 Schmoller represented the Berlin University in the Herrenhaus and in the same year became a member of the peace class of the “ Pour le Mérite ”. Honorary doctorates (1896 from the Faculty of Law in Wroclaw, 1903 from the Philosophical Faculty in Heidelberg), medals (so in 1908 with the Bavarian Maximilian Order for Sciences ) and numerous appointments as corresponding members of foreign academies and societies testified to the respect that his person and his scientific achievements at home and enjoyed abroad. He was able to make full use of this scholarly life into old age.

Gustav von Schmoller died just three days after his 79th birthday on June 27, 1917 on a trip to Bad Harzburg. His grave is in the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Cemetery in Berlin-Westend . The simple grave wall without structure made of shell limestone with a limestone stele in front that serves as a tombstone is composed in the functional style of contemporary burial culture. The facility was restored after being damaged during the Second World War. Schmoller rests next to his wife Lucie geb. Rathgen (1850-1928).

By decision of the Berlin Senate , the grave of Gustav von Schmoller (grave site B 1 grid 3) has been dedicated as an honorary grave of the State of Berlin since 1956 . The dedication was extended in 2016 by the usual period of twenty years.

Part of the estate is in the Tübingen University Library .

Influences from the political and social environment

His father, in whose office he learned administrative business from scratch, and his brother-in-law Gustav Rümelin, of whom Schmoller himself said: "Without his influence, I would probably not have become what I was, had an important and formative influence on the personality of the young Schmoller am ".

During his studies Schmoller received the strongest impressions from the lectures of Max Duncker (later head of cabinet to Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm), in whose house the student from Tübingen also frequented.

The relationship with Rümelin was beneficial, and she made the acquaintance of numerous Tübingen professors. It is difficult to determine where Schmoller got his Catholic Socialist orientation. It is possibly due to Schmoller's direct contact with ordinary people and their needs. He got to know everyday reality in Heilbronn better than many economists who were only arrested in academic life. Schmoller never wanted to live in the ivory tower of science.

The German Empire, newly formed in 1871 under Prussian leadership, seemed the right partner to set social reforms in motion with new ideas and goals. Methodologically and theoretically, Karl Knies had the strongest influence on Schmoller, whose "Political Economy from the Historical Viewpoint (1853)" he described in 1888 as a common creed. He referred to this in his dissertation, for example, as follows: “So we must place economics in the series of the social sciences, which cannot be separated from the conditions of space, time and nationality, the justification of which we do not alone, but preferably in of history ”(preface to the dissertation). Schmoller's conception of theory was fundamentally different from that which had been established by the classical period. In 1914 Schmoller was one of the signatories of the 93 .

Schmoller was one of the first German professors to encourage women to study at university. Elisabeth Gnauck-Kühne, a social economist, is one of his students .

Scientific achievement

Schmoller and the historical-realistic, psychological-ethical approach he advocated experienced a high point of activity and influence. The number of his students and followers was just as great as his influence on political economy at German universities. Appreciating Schmoller's work as a scientist as a whole remains difficult, as he was neither a theorist nor can he be classified as an economic politician; he was a representative of interdisciplinary science. The economic and social historians can count Schmoller among their ancestors as well as the social or economic politicians.

In the methodological explanations of his outline, he certainly allows abstract-deductive theory to apply alongside the inductive-descriptive method, but he makes it clear that his sympathy, his conviction of better performance lies with the latter. Schmoller: "Anyone who is based on experience never trusts deductive conclusions without further ado." Schmoller was guided by the idea of explaining the individual important development series of economic life psychologically, legally and economically, to appreciate them socio-politically, theirs to demonstrate future development trends. The connection between morality, custom and law was particularly important to him as factors of economic development in the past as well as for the future, i.e. precisely those influencing factors that are not or only inadequately captured by the exact national economic theory. He vigorously denied that the truth found in the isolating, abstract experiment can serve as a basis for knowledge. Man does not behave according to theory, but is subject to the most varied motives in his actions.

Turning against Carl Menger , the great theorist of political economy and founder of the Austrian school of marginal utility, Schmoller demanded that all essential causes of the economic phenomenon be examined. This dispute came to be known as the method controversy .

With his emphasis on the psychological fundamentals, Schmoller also became one of the pioneers of the new "understanding sociology" of Max Weber or Werner Sombart . For him, psychology and philosophy were important components of scientific observation.

Works

- On the history of economic views in Germany during the Reformation period. In: Journal for the entire political science , Vol. 16 (1860).

- The French trade treaty and its opponents , 1862.

- The doctrine of income in relation to the basic principles of taxation. In: Journal for the entire political science , Vol. 19 (1863).

- Systematic representation of the result of the customs purposes in the year 1861 in Württemberg instead of held business start-up. In: Württemberg, Statistics and Topography , 1863.

- The worker question. Art. I-III. In: Prussian year books , vol. 14 and vol. 15 (1864/65).

- On the history of German small businesses in the 19th century. Statistical and national economic studies. 1870. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- On the Results of Population and Morale Statistics , 1871.

- The social question and the Prussian state. In: Prussian Yearbooks , Vol. 33 (1874).

- About some basic questions of law and economics. An open letter to Professor Dr. Heinrich von Treitschke. In: Yearbook for Economics and Statistics , Vol. 23 and Vol. 24 (1874/75).

- Strasbourg's heyday and the economic revolution in the 13th century, 1875.

- The Strasbourg cloth and weaver guild. A contribution to the history of German weaving and German trade law from the 13th to the 17th century, 1879 ( digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf )

- On the literary history of political and social sciences. 1888.

- On the social and commercial politics of the present. 1890.

- Economics, economics and its method. 1893 ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Friedrich Wilhelm I's political will of 1722. 1896.

- The Prussian Trade and Customs Act of May 26, 1818 in connection with the history of the time, its struggles and ideas 1898.

- Changing theories and established truths in the field of political and social sciences and today's German economics. Rector's speech in Berlin, 1897.

- About some basic questions of social politics and economics. 1898.

- Outlines and studies of the constitutional, administrative and economic history, especially of the Prussian state in the 17th and 18th centuries. 1898.

- To Bismarck's memory. 1899 (together with Max Lenz and Erich Marcks ).

- Some principled discussions about value and price. 1901.

- About the machine age in its connection with the national prosperity and the social condition of the national economy. 1903.

- About bodies for unification u. Arbitration awards in labor disputes. 1903.

- Outline of general economics. 1900/1904 2 volumes (volume 1 digitized and full text in the German text archive ) (digitized edition of volumes 1 and 2 under: urn : nbn: de: s2w-8307 )

- The Development of German Economics in the Nineteenth Century. 1908.

- Character images. 1913.

- The social question - class formation, workers question, class struggle. 1918.

- My early years in Heilbronn. 1918.

- Twenty years of German politics - (1897–1917). 1920 ( online - Internet Archive ).

- Prussian constitutional, administrative and financial history. 1921 ( online - Internet Archive ).

- German urbanism in older times. 1922 ( online - Internet Archive ), (ND 1964).

Honors

Incomplete list

- Really Go advice

- Ennobled by Wilhelm II (German Empire) as King of Prussia

- Member of the Pour le Mérite order in 1899

- Bust of the sculptor Wilhelm Wandschneider for Schmoller's 70th birthday (preserved at the Humboldt University Berlin)

- His grave has been dedicated to the honor grave of the city of Berlin since 1956 .

- Name of a street at the Südbahnhof in Heilbronn (Schmollerstraße)

- Designation of a street and a town square in the northwest of the Berlin district of Alt-Treptow in the Treptow-Köpenick district ( Schmollerplatz )

literature

- Acta Borussica , Volume 10 (1909-1918) (PDF; 2.74 MB).

- Pauline R. Anderson: Gustav von Schmoller. In: Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Deutsche Historiker , Volume 2, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1971, pp. 147–173.

- Hans-Otto Binder : Schmoller, Gustav. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 9, Bautz, Herzberg 1995, ISBN 3-88309-058-1 , Sp. 506-510.

- Knut Borchardt : Schmoller, Gustav Friedrich von (Prussian nobility 1908). In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , pp. 260-262 ( digitized version ).

- Genealogical handbook of the nobility , noble houses. B Volume XIII, Volume 73 of the complete series, CA Starke Verlag, Limburg (Lahn) 1980, ISSN 0435-2408 , p. 344.

- Eckhard Hansen, Florian Tennstedt (Eds.) U. a .: Biographical lexicon on the history of German social policy from 1871 to 1945 . Volume 1: Social politicians in the German Empire 1871 to 1918. Kassel University Press, Kassel 2010, ISBN 978-3-86219-038-6 , pp. 139 f .; uni-kassel.de (PDF; 2.2 MB).

- Jens Herold: The young Gustav Schmoller. Social science and liberal conservatism in the 19th century , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-525-31722-8 .

- Birger P. Priddat: The other economy. About G. v. Schmoller's attempt at an “ethical-historical” economy in the 19th century. Metropolis, Marburg 1995.

- Bertram Schefold : The great economists . Schäffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-7910-1044-1 .

- Arthur Spiethoff : Gustav von Schmoller and German historical economics . Duncker & Humblot, 1938. (Reprint: ISBN 978-3-937872-92-6 )

- Joachim Starbatty (ed.): Classics of economic thinking. Nikol Verlag, 1989. (New edition 2008, ISBN 978-3-937872-92-6 )

Web links

- Literature by and about Gustav Schmoller in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Gustav von Schmoller in the German Digital Library

- Works by Gustav von Schmoller in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Gustav von Schmoller in the Internet Archive

- Newspaper article about Gustav von Schmoller in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Gustav Friedrich von Schmoller . Humboldt University of Berlin

- Entry on Gustav von Schmoller in the Catalogus Professorum Halensis

Individual evidence

- ↑ Borchardt, Knut: Schmoller, Gustav Friedrich v .. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , p. 260 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Hans-Heinrich Bass: SMEs in the German economy: past, present, future . ( Memento from December 15, 2017 in the Internet Archive ; PDF; 96 kB) (Reports from the World Economic Colloquium of the University of Bremen, No. 101, June 2006, ISSN 0948-3829 ) p. 4.

- ↑ See his speech on the 25th anniversary of the association in 1897, in: Collection of sources for the history of German social policy 1867 to 1914 , III. Department: Development and Differentiation of Social Policy since the Beginning of the New Course (1890–1904) , Volume 1, Basic Questions of Social Policy , edited by Wolfgang Ayaß , Darmstadt 2016, No. 108.

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Mende : Lexicon of Berlin burial places . Pharus-Plan, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-86514-206-1 , p. 480.

- ↑ Honorary graves of the State of Berlin (as of November 2018) . (PDF, 413 kB) Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection, p. 78; accessed on March 22, 2019. Recognition and further preservation of graves as honorary graves of the State of Berlin . (PDF, 205 kB). Berlin House of Representatives, printed matter 17/3105 of July 13, 2016, p. 1 and Annex 2, p. 14; accessed on March 22, 2019.

- ↑ Federal Archives, Central Database of Legacies, accessed on September 11, 2019.

- ↑ Printed in: Collection of Sources for the History of German Social Policy 1867 to 1914 , Section I: From the Founding of the Reich to the Imperial Social Message (1867–1881) , Volume 8: Basic Social Policy Issues in Public Discussion: Churches, Parties, Associations and Associations , edited by Ralf Stremmel, Florian Tennstedt and Gisela Fleckenstein, Darmstadt 2006, No. 5 and No. 9.

- ^ Pour le Merit: Members of the Order. Retrieved December 5, 2017 .

- ↑ Schmollerplatz. In: Street name dictionary of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (near Kaupert ) Schmollerstraße. In: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (near Kaupert )

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schmoller, Gustav von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schmoller, Gustav Friedrich von |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German economist; was considered the leader of the so-called "historical school" |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 24, 1838 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Heilbronn |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 27, 1917 |

| Place of death | Bad Harzburg |