Otto von Bismarck

Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck-Schönhausen , from 1865 Count von Bismarck-Schönhausen , from 1871 Prince von Bismarck , from 1890 also Duke of Lauenburg (born April 1, 1815 in Schönhausen (Elbe) ; † July 30, 1898 in Friedrichsruh near Aumühle ) , was a German politician and statesman . From 1862 to 1890 - with a brief interruption in 1873 - he was Prime Minister of Prussia and from 1867 to 1871 he was also Federal Chancellor of the North German Confederation. From 1871 to 1890 he was the first Chancellor of the German Empire , the establishment of which he played a key role. Bismarck is considered to be the perfecter of German unification and the founder of the welfare state of the modern age .

As a politician, Bismarck first made a name for himself in Prussia as a member of the First United State Parliament with predominantly conservative positions. He was a diplomat for the Bundestag of the German Confederation as well as in Russia and France from 1851 to 1862 . In the Prussian constitutional conflict , he was appointed Prime Minister by King Wilhelm I in 1862 . In the fight against the liberals, Bismarck defied parliament and was able to solve the German question in the small German sense under the predominance of Prussia in the German-Danish War and the German War between 1864 and 1866 . In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 he was the driving force behind the establishment of the German Empire .

As Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister, he played a decisive role in the policy of the newly created empire until his dismissal in 1890. In terms of foreign policy, he relied on a balance between the European powers (→ Otto von Bismarck's alliance policy ) and for a long time turned against a German colonial policy .

Domestically, his reign after 1866 can be divided into two phases. First there was an alliance with the moderate liberals. During this time there were numerous domestic political reforms such as the introduction of civil marriage , whereby Bismarck fought resistance on the Catholic side with drastic measures (→ Kulturkampf ). From the late 1870s onwards, Bismarck increasingly turned away from the liberals. In this phase the transition to protective tariff policy and state interventionist measures falls . This included, in particular, the creation of the social security system . Domestically, the 1880s were shaped not least by the repressive socialist law . In 1890 differences of opinion with Kaiser Wilhelm II, who had been in office for almost two years, led to Bismarck's dismissal.

In the years that followed, Bismarck still played a certain political role as a critic of his successors. In particular through his much-read memoir, Thoughts and Memories, he himself played a decisive and lasting role in his image in the German public. In popular parlance and historiography , Bismarck was also called the "Iron Chancellor".

Until the middle of the 20th century, German historiography was dominated by an extremely positive assessment of Bismarck's role, which in some cases bore traits of idealization. After the Second World War , critical voices increased who made Bismarck jointly responsible for the failure of democracy in Germany and portrayed the empire he had shaped as a misconstruction of the authoritarian state . More recent representations mostly overcome this sharp contrast, whereby the achievements and shortcomings of Bismarck's politics are equally emphasized, and show him as embedded in contemporary structures and political processes.

Early years

Origin, youth and education

Otto von Bismarck was born on April 1, 1815 at Schönhausen Castle near the Elbe near Stendal in the province of Saxony as the second son of Rittmeister Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Bismarck (1771–1845) and his wife Luise Wilhelmine, née Mencken (1789–1839) , born. He was paternal scion of the old noble family Bismarck , a landsässigen Uradelsgeschlechts the Altmark , which since the beginning of the 18th century at the same time in Pomerania in Pomerania had three goods. His mother was of bourgeois origin, her father Anastasius Ludwig Mencken was Frederick the Great's secret cabinet secretary . The Mencken family had produced scholars and high officials in the past. Otto von Bismarck's older brother, Bernhard von Bismarck (1810-1893), became District Administrator and Privy Councilor. The later sister Malwine (1827-1908) married the district administrator of the Angermünde district, Oskar von Arnim-Kröchlendorff .

In 1816, the young family moved, without giving up the Schönhausen estate, to the Kniephof estate in western Pomerania , where Otto von Bismarck spent the first years of his childhood.

The different social origins of the parents had significant consequences for Bismarck's socialization. He inherited his pride in his origins from his father; his mother not only gave him his keen intellect, a sense of rational action and linguistic sensitivity, but also the desire to escape from his circle of origin. Bismarck was thanks to his mother that he enjoyed an education that for a scion of the less for a country gentleman than the educated middle class was common. Their sons were not only supposed to be Junkers, they were supposed to join the civil service. However, the strictly rational upbringing of his mother meant that, as he later wrote, Bismarck never really felt at home in his parents' house. While he was reserved towards his mother, he loved his father.

Education

At the age of six, Bismarck's school education began in 1821 at the request of his mother in the Prussian capital Berlin in the Plamann educational institution . This boarding school, to which high officials used to send their sons, was originally founded in the spirit of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi . By the time of Bismarck, this phase of reform had long since ended and the upbringing was characterized by drill and German drudgery. Bismarck found the transition from childish play on the home farm to boarding school life, which was characterized by coercion and discipline, extremely difficult. During this time his unwillingness to recognize authorities was clearly expressed.

In 1827 Bismarck moved to the Berlin Friedrich-Wilhelms-Gymnasium , from 1830 he attended the humanistic Berlin Gymnasium at the Gray Monastery until he graduated from high school in 1832 . With the exception of ancient Greek , which Bismarck soon saw as superfluous, at school he showed himself to be extremely talented in languages, even if not always as hard-working.

religion

Bismarck was a member of the Lutheran denomination. He received religious instruction from Friedrich Schleiermacher , who also confirmed the sixteen-year-old in the Trinity Church in Berlin . During this time, Bismarck dealt with questions of religion mainly from the point of view of the intellect and, in retrospect , saw himself in it, influenced by Hegel or Spinoza , more as a deist and pantheist than as a devout Christian. However, he was never an atheist, even if those around him mostly regarded him as an ungodly mocker. During his legal clerkship, he wrote to his brother Bernhard in 1836: "I only notice that you do not expect me to be too prudent if you consider me an atheist." Christianity intervened decisively in his life when he unexpectedly died Friend Marie von Thadden-Trieglaff met.

Study and training

After graduating from high school, Bismarck began studying law at the age of seventeen on May 10, 1832 (1832-1835), initially at the University of Göttingen (1832-1833), which later also awarded him an honorary doctorate on the occasion of his 70th birthday. He emphatically rejected the political aftermath of the July Revolution . It was therefore no coincidence that he did not join the fraternities , which were opposition at the time , but the striking country team student union Corps Hannovera Göttingen . He remained a staunch corps student throughout his life. What he disliked about the fraternities was “their refusal to give satisfaction and their lack of external upbringing and forms of good society, as well as, on closer acquaintance, the extravagance of their political views, which are based on a lack of education and knowledge of the existing, historical ones Living conditions was based ". He later summarized his observations to the remark that it was a matter of a connection between utopia and lack of education. On the other hand, he described himself as in no way influenced by Prussian monarchical ideas. History and literature interested him, law studies less. The only academic teacher who impressed and probably influenced him was the historian Arnold Heeren , who outlined the functioning of the international state system in his lectures. He built closer personal relationships with his corps brother Gustav Scharlach and the later American diplomat John Lothrop Motley , who remained one of his few personal friends throughout his life.

In November 1833 Bismarck continued his studies at the Friedrich Wilhelms University in Berlin . In 1835 he graduated with the first state examination. Then he was initially an auscultator at the Berlin City Court. At his own request, he switched from judicial to administrative service. He was not only looking for diversion in the circle around the novelist Carl Borromäus Cünzer : Soon bored of the day-to-day office work of a government trainee in the fashionable spa town of Aachen , he fell in love with Laura Russell, a niece of the Duke of Cumberland , in August 1836 . After the affair with an (older) French woman, he traveled through Germany in the summer of 1837 with a (younger) English woman, a friend of Laura Russell. This resulted in a fourteen-day holiday being exceeded for several weeks, which meant that he lost his legal clerkship.

Bismarck struggled with expenses for women and also incurred debts by visiting casinos. He stayed away from official business for months. He later tried to continue his traineeship training in Potsdam , but turned his back on administrative work after a few months. He explained this step in retrospect by saying that he did not want to be a mere cog in the gears of the bureaucracy: "But I want to make music as I see it as good, or none at all."

military service

In 1838 Bismarck did his military service as a one-year volunteer , initially with the Guard Jäger Battalion . In autumn he moved to the Jäger Battalion No. 2 in Greifswald in Western Pomerania, where he also prepared for the management of family businesses at the Royal State and Agricultural Academy in Eldena .

Bon vivant and successful estate manager

After the death of his mother in 1839, Bismarck moved into the Kneephof estate in western Pomerania and became a farmer. Together with his brother Bernhard, who was five years older than him, he managed the paternal estates Kniephof, Külz and Jarchlin in the Naugard district . After Bernhard von Bismarck had been elected district administrator in 1841, it was temporarily divided. Bernhard now managed Jarchlin, Otto Külz and Kniephof. After his father's death in 1845, Otto took over the management of the Schönhausen family estate near Stendal .

Bismarck quickly acquired a good knowledge of rational agricultural management. In the ten years or so in which he acted as administrator of his parents' property, he not only succeeded in restoring the property, but also in repaying his own debts that he had accumulated over the past few years.

On the one hand he liked being his own master, on the other hand he was not satisfied with the agricultural activity and the life as a squire. At the same time, he dealt intensively but unsystematically with philosophy, art, religion and literature, without this having had a lasting impact on him. In 1842 he went on a study trip to France, England and Switzerland. He gave up trying to return to civil service in 1844 - again because of his aversion to everything bureaucratic. During these years he was a welcome guest at numerous social events in the region. Among other things, he took part in numerous hunting events, but also in excessive carousing parties. According to his own statements, he had acquired a kind of drinkability in this context; with the squires he had gained in respect because he was able to "drink his guests under the table with friendly cold-bloodedness". This, as well as his tendency to be the center of attention at social events, earned him the reputation of the "great Bismarck".

Wife and children

Through Moritz von Blanckenburg , a school friend from Berlin, Bismarck came into contact with the pietistic group around Adolf von Thadden-Trieglaff . Blanckenburg was engaged to his daughter Marie von Thadden-Trieglaff . She and Bismarck felt like kindred spirits, but for the young woman breaking up her engagement was out of the question. In October 1844 she married Blanckenburg. At the wedding reception she chose her twenty-year-old friend Johanna von Puttkamer to be the table lady for Bismarck. In the summer of 1846, the married couple Blanckenburg, Bismarck and Johanna von Puttkamer traveled to the Harz Mountains together . Marie died on November 10, 1846 after a brief, serious illness. Shortly before Christmas 1846, Bismarck asked for Johanna's hand in a now famous letter to Heinrich von Puttkamer. The latter answered hesitantly; Bismarck then traveled to Reinfeld near Rummelsburg in Western Pomerania at the beginning of 1847 and convinced Johanna's parents in a personal conversation.

The marriage took place in Reinfeld ( Rummelsburg i. Pom. District ) in 1847 . Since then, belief in a personal God has played a central role for Bismarck.

The marriage with Johanna von Bismarck had three children:

- Marie (1848–1926), ∞ Kuno Graf zu Rantzau

- Herbert (1849–1904), ∞ Marguerite Countess von Hoyos

- Wilhelm (1852–1901), ∞ Sibylle von Arnim-Kröchlendorff

Johanna subordinated her needs to those of her husband and at the same time offered him - unlike his mother - a firm emotional bond. The letters the two exchanged were among the highlights of the 19th century letter literature.

Political beginnings

Conservative agitator

Bismarck initially emerged politically at the local level. During his time at Gut Kniephof he was a deputy of the Naugard district , in 1845 he became a member of the provincial parliament of the province of Pomerania and in some cases supported his brother in his work as district administrator. Through his pietistic circle of friends he came into contact with leading conservative politicians around 1843/1844, in particular with the brothers Ernst Ludwig and Leopold Gerlach . In 1845, not least to expand this connection, he leased the Kniephof and moved to Schönhausen. This place was closer to Magdeburg , the then official seat of Ludwig von Gerlach. Bismarck received his first public office in 1846 when he was appointed dike captain in Jerichow .

His main concern during this time was to preserve the supremacy of the land-owning nobility in Prussia. The conservatives rejected the absolutist-bureaucratic state and dreamed of a re-establishment of the co-government of the estates, especially the nobility. Together with the Gerlach brothers, for example, Bismarck advocated the preservation of patrimonial jurisdiction .

As a successor in the Saxon provincial parliament , Bismarck became a member of the United Landtag in 1847 as a representative of the knighthood of the province of Saxony . In this body, which was dominated by the moderate liberal opposition , he was already noticed in his first plenary speech as a strictly conservative politician when he denied that the liberal reforms had also been implemented during the wars of liberation . In the “Jewish question” he spoke out clearly against the political equality of the Jewish population. These and similar positions led to indignant reactions from the Liberals. During this time, Bismarck found a field of activity in politics that suited his inclinations: "The matter affects me much more than I thought."

The passion of the political struggle made him hardly eat or sleep. At the end of the meeting, Bismarck had made a name for himself in conservative circles. The king too had noticed him. Even though he took a clearly conservative position, Bismarck was also a pragmatist at this time and ready to learn from his political opponents. This came into play, for example, in the plan to found a conservative newspaper as a counterweight to the liberal Deutsche Zeitung .

Bismarck resolutely rejected the March Revolution . When the news of the movement's success in Berlin reached him, he armed the peasants in Schönhausen and suggested that they move to Berlin with them. However, General Karl von Prittwitz , who was in command in Potsdam, refused this offer. Then Bismarck tried to convince Princess Augusta , the wife of the heir to the throne Wilhelm, of the need for a counter-revolution. Augusta rejected the request as scheming and disloyal. Bismarck's behavior attracted the permanent dislike of the future queen. After Friedrich Wilhelm IV recognized the revolution , Bismarck's counter-revolutionary plans initially failed.

Bismarck was not elected to the Prussian National Assembly. For this he took part in the extra-parliamentary collection of the conservative camp. In the summer of 1848 he was involved in founding and developing the content of the Neue Preußische Zeitung (also known as the Kreuzzeitung because of the cross on the title page ). He wrote numerous articles for the paper. In August 1848 he was one of the main initiators of the so-called Junker Parliament . Several hundred aristocratic landowners gathered here to protest against the encroachment on their property.

These activities meant that the conservative camarilla around King Bismarck began to appreciate more and more. However, his hope of being rewarded with a ministerial post after the counter-revolution in November 1848 was not fulfilled, as he was considered too extreme even in conservative circles. The king wrote on a corresponding list of suggestions as a side note: "Only to be used if the bayonet is unrestricted".

Turning to Realpolitik

In January and July 1849 Bismarck was elected to the second chamber of the Prussian state parliament. During this time he decided to devote himself entirely to politics and moved to Berlin with his family. This made him one of the first professional politicians in Prussia. In the state parliament he appeared as the mouthpiece of the ultra-conservatives. He defended the rejection of the imperial dignity and the imperial constitution by Friedrich Wilhelm IV, because from his point of view it was to be feared that Prussia would become part of Germany. For him, the national question was secondary to securing Prussian power.

The king and his advisor Joseph von Radowitz wanted to achieve German unity primarily through consultation with the middle states. In addition, the desired Erfurt Union should be more conservative and federalist than the Frankfurt model. Bismarck found this unrealistic and meaningless. In the Prussian parliament he made no secret of his criticism of the plans. His speech of September 6, 1849 changed the attitude of interested political circles towards him. From then on, he was no longer just a harassment because of his deliberate and flexible argumentation, even in his own conservative ranks. Bismarck recommended himself for the first time for a post in high civil service or in diplomacy . Despite his criticism of the Union, he was elected to the Volkshaus of the Erfurt Union Parliament and became its secretary.

Although he was fundamentally opposed to parliamentarianism, Bismarck developed into one of the most important parliamentary speakers of the time in Erfurt, to whom his political opponents also paid attention because of his language rich in images and punch lines. After the failure of the union plans, Bismarck took on the difficult task of defending the Olomouc punctuation in the Prussian state parliament . He managed on the one hand to take conservative standpoints, but on the other hand to commit himself to a state power politics far removed from any ideologies: “The only healthy basis of a large state, and this differs significantly from a small state, is state egoism and not romanticism, and it is not worthy of a great state to fight for a cause that does not belong to its own interests. ”With his emphasis on the state, power and interest politics, Bismarck distanced himself from traditional conservatism, which (in a more defensive Basic attitude) arose out of opposition to the modern, central, bureaucratic and absolutist state.

diplomat

Bundestag envoy

On August 15, 1851, at the instigation of Leopold von Gerlach, Bismarck was appointed Prussian envoy to the Bundestag in Frankfurt by Friedrich Wilhelm IV . He had no diplomatic training and the king was also very suspicious. After the Olomouc punctuation , Prussia was forced to fill the position of the Bundestag envoy. Although you really couldn't break any political china in this position, nobody believed that Bismarck was the right person. Bismarck had to assure the questioning king that he would stand back if he was not up to the task:

“Courage is entirely on Your Majesty's part if you entrust me with such a position; however, Your Majesty is not bound to maintain the appointment as soon as it fails. I myself cannot be certain whether the task is beyond my abilities until I have approached it. If I find myself unable to cope there, I will be the first to ask for my recall. I have the courage to obey when your Majesty has orders. "

Finally, the ambassador to Russia Theodor von Rochow was appointed, who was accompanied by Bismarck at the insistence of Leopold von Gerlachs . Both of them arrived in Frankfurt on May 11, 1851, and on July 15, 1851, Bismarck replaced Rochow as Minister of the Bundestag, who in turn returned to his embassy in Petersburg. Bismarck's first action in Frankfurt was to support the federal reaction decision . Therefore his appointment was seen by the public as a sign of the victory of the social and political reaction as well as a surrender of Prussia to Austria.

In Frankfurt, Bismarck acted very independently. At times it was in opposition to the Berlin government policy. However, as envoy, he made it clear that he was still a man of the highly conservative. His position in a chamber debate led to the Vincke – Bismarck duel on March 25, 1852 , in which neither of the two duelists was hit.

When Prussia and the Austrian Empire worked together after the autumn crisis of 1850 , Bismarck did not want to accept that the Austrian Prime Minister Felix zu Schwarzenberg intended Prussia to play the role as a junior partner. For him and ultimately also for the government in Berlin, it was a matter of enforcing the recognition of Prussia as an equal power. To this end, he constantly sought a dispute with the Austrian envoy Friedrich von Thun and Hohenstein , attacked Vienna sharply and temporarily paralyzed the work of the Bundestag in order to show the limits of Austrian competencies in Frankfurt. He also contributed to the failure of Austria's wish to join the German Customs Union. Bismarck rejected an expansion of the institutions and a federal reform in general , as long as Austria did not treat Prussia as equal.

The decision of the Prussian government in 1854 (against the background of the Crimean War ) to renew the protective and defensive alliance with Austria met with criticism from Bismarck. When Austria then turned openly against Russia, Bismarck succeeded in 1855 by clever tactics in averting the Austrian request to mobilize the federal troops against Russia. This success increased his diplomatic reputation. After the defeat of Russia in the Crimean War, he pleaded in various memoranda for a reference to the tsarist empire and France, through which he hoped to weaken Austria further. He laid down his foreign policy concept in great detail in the “splendid publication” of 1856. His remarks sparked a violent conflict with the highly conservative around the Gerlach brothers , who in Napoleon III. saw only a proponent of the revolutionary principle and a "natural enemy". Bismarck replied that he ultimately did not care about the legitimacy of the heads of state. For him, it was not the conservative principles, but the state interests in the diplomatic business that were the focus. In the conservative camp, he was now increasingly seen as a selfish opportunist.

Bismarck attached great importance to Prussia's neutral stance in the Crimean War and to its independent position at the conference in Paris that led to the Paris Peace of 1856 . So he did not like the fact that, in addition to England, Austria was also exerting pressure in Berlin and Frankfurt to force Prussia to go to war in the service of the Western powers. In contrast, Napoleon III. much more forgiving of these "sins".

Envoy to St. Petersburg and Paris

The conflict with the Gerlachs also had domestic political reasons. After Prince Wilhelm took over the reign in 1857, the highly conservatives lost their influence; instead, the moderately liberal-conservative weekly paper party increased in importance. In the beginning of the New Era , Bismarck also tried to maintain his position by distancing himself from the extreme conservatives. In an extensive memorandum, he now spoke of a “national mission” by Prussia and of an alliance with the national-liberal movement. With that he made a remarkable change of course. However, his aim was not to fight for German unity for its own sake, but rather to make German nationalism serve to strengthen Prussian power.

The expectations that he associated with adapting to a changed political climate in Prussia were not initially fulfilled for him. In January 1859 he was transferred to Saint Petersburg as the Prussian envoy ; he himself spoke of having been sidelined on the Neva . The change was difficult for the family; The Bismarck couple had had the happiest time of their marriage in Frankfurt. In his new role, however, Bismarck expanded his diplomatic knowledge and enjoyed the goodwill of the Russian court and the imperial couple. But his ambition was increasingly directed towards the highest offices in the Prussian state. He closely observed the development of the Prussian constitutional conflict . The hope of being appointed Prime Minister in April 1862 was not fulfilled. Instead he became an envoy in Paris , where he resided in the Palais Beauharnais . From the start, however, this post was only considered a waiting position.

During this time, his wife tolerated his love affair with Princess Katharina Orlowa (1840–1875), wife of the Russian envoy in Belgium Nikolai Alexejewitsch Orlow . On August 22, 1862, shortly before his appointment as Prime Minister, Bismarck almost drowned in Biarritz with Katharina Orlowa and was rescued by a lighthouse keeper. On that day he only wrote to his wife: "After a few hours of rest and writing letters to Paris and Berlin, I took the second drink of salt water, this time in the harbor, without the waves, with a lot of swimming and diving, two wave pools would be too much for me during the day." It was Bismarck's last private escapade before he devoted himself exclusively to politics.

Prussian Prime Minister

vocation

In Berlin the negative attitude of the Liberals against a planned army reform became more solid . The political public did not seriously question the need to modernize the army. However, the dispute was sparked by military-political details. Among other things, the Prussian King Wilhelm I was not prepared to abandon his plan of three instead of two years of military service. This made it impossible to reach an agreement with the Prussian state parliament. In this seemingly hopeless situation, Wilhelm I brought a possible resignation in favor of his son, the future Emperor Friedrich III. in the game.

War Minister Roon saw in the appointment of Bismarck as Prime Minister the only way to prevent the change of the throne in favor of the liberal Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm . With a telegram - “ Periculum in mora. Dépêchez-vous! "(" Imminent danger. Hurry up! ") - he called Bismarck back to Berlin. After a 25-hour train journey, Bismarck arrived in Berlin on September 20, 1862. Two days later he was received by King Wilhelm I in Babelsberg Palace . Only Bismarck's report is available on the content and course of the conversation, but in contrast to other parts of his memoirs, it should be essentially correct. Bismarck won the still hesitant king by pretending to be his absolute follower. He promised the implementation of the army reform and, for his part, emphasized the fundamental importance of the dispute over it. The king finally appointed Bismarck prime minister and foreign minister.

Relationship with the King and Principles

The appointment interview laid the foundation for the extraordinary relationship between the king and Bismarck in the decades that followed. Bismarck created the basis for an extraordinary position of trust with Wilhelm I and obtained a blanket power of attorney that expanded his room for maneuver beyond the usual extent of a leading minister ( Lothar Gall ) by offering himself to the monarch as a "Kurbrandenburg vassal" who served in in a precarious situation, brave to fight and in unswerving loyalty to his liege lord. In the years that followed, there were repeated differences of opinion, but they did not affect King Bismarck's basic trust.

In particular, Bismarck was given very strong powers, which he later referred to. One of them was that his ministers were only allowed to report to the monarch individually with his consent .

Bismarck remained a conservative, but an increasingly pragmatic politician who did not cling to ideological fixations. Ideals, theories and principles were not primarily decisive for him; what counted above all were the interests of the states. This resulted in the expansion of Prussia as a decisive goal. From Bismarck's point of view, it was only possible to preserve Prussia's claim to great power if it could gain a hegemonic position in Europe at the expense of Austria and if the other European powers tolerated it. To nationalism in the usual sense, it was not his doing, but to foreign policy realism. He insisted that foreign policy successes would also have a positive effect on his domestic policy. He wanted to preserve the monarchy and the authoritarian state as well as the special position of the military and the nobility. In cases of doubt, however, the first priority was the power of the state. This was also the aim of the temporary alliance with the national and liberal movement.

Conflict minister

At the beginning of his ministerial presidency, a rejection of Bismarck's policy prevailed in large parts of the political public. He was still considered an extreme reactionary and therefore had a hard time finding suitable ministers. The first Bismarck cabinet consisted for the most part of rather secondary personalities. Among them were Carl von Bodelschwingh , Heinrich Friedrich von Itzenplitz and Gustav von Jagow . As head of a conflict ministry, Bismarck was initially involved in a dispute with the liberals.

At first he tried to neutralize the opposition through compensatory efforts. This failed because his blood-and-iron speech once again seemed to confirm the image of a very conservative politician:

“Germany does not look to Prussia's liberalism, but to its power. [...] The big questions of the time are not decided by speeches and majority decisions [...] - but by iron and blood. "

The speech was intended as a far-reaching alliance offer to the liberal and national movement. Although the liberal majority in the House of Representatives was of the opinion that the “ German question ” could not be enforced without violence, it was understood, especially the (liberal) press, “iron and blood” as an announced tyranny, which plunged into foreign policy adventures . This has helped to cement Bismarck's reputation as a violent politician. As a result, Bismarck gave up his lurching course and fought the liberals with all sharpness. Parliament was adjourned. Bismarck thus ruled in the autumn of 1862 without a proper budget. Parliament was convened again in early 1863. Bismarck justified himself with the famous, heavily controversial gap theory . After that, normal government action is based on compromises between the crown, the manor and the House of Representatives. If one of the sides refuses to give in, conflicts arise, “and conflicts, since state life cannot stand still, become questions of power; whoever has power in his hands then proceeds in his own way, because state life cannot stand still for a moment ”.

Behind this was Bismarck's premise that the case of an indissoluble dissent between monarch and parliament was not regulated in the constitution . Accordingly, there is a loophole that must be closed by the prerogative of the king. In the opinion of many contemporaries, this interpretation of the legal situation was simply a breach of the constitution. Maximilian von Schwerin-Putzar judged that this means "power comes before law". So far, the size of Prussia and the recognition of the royal family have been based on the principle “Right comes before power. Justitia fundamentum regnorum! That is the motto of the Prussian kings, and it will remain so on and on. "

In order to mobilize against the liberals, Bismarck pursued different plans at times. This also included an alliance with the social democratic movement . In 1863 he met Ferdinand Lassalle several times without this having any practical impact at the time.

Despite violent protests - public criticism even came from the heir to the throne - and the general expectation that the government would fail, Bismarck survived the crisis politically. He used repressive means up to and including dismissals against high-ranking liberal officials, including not least MPs. At the same time, freedom of the press was practically abolished in disregard of the constitution. In 1865, Bismarck challenged Professor Rudolf Virchow (a member of the Prussian House of Representatives) to a duel, but the latter refused because it was not a contemporary form of argument.

Of course, nothing changed in the political situation. The constitutional crisis remained unsolved until 1866 and degenerated into something like a positional war. Bismarck tried to wear down the opposition. He ruled with the state apparatus, and for a long time parliament was not even convened. It was dissolved again on May 9, 1866. Bismarck initially toyed with the idea of a coup d'état by abolishing the right to vote and the constitution. The longer the conflict lasted, the more he rejected such demands, which were made by the conservative side, but because they did not promise a long-term stable political order.

Meanwhile, Bismarck tried to exert domestic pressure on the opposition with successes in foreign policy. At first this calculation only worked to a limited extent. The first agreement, the Alvensleben Convention of February 8, 1863, in support of Russia against the uprising in Poland , met with widespread opposition in Prussia, even in conservative circles. The pressure from Great Britain and Napoleon III. moreover made the convention worthless.

Austria saw Bismarck weakened and tried to use this to implement a reform of the German Confederation in favor of the Habsburg monarchy . Bismarck succeeded only with difficulty in dissuading the king from participating in the planned Prince’s Day in Frankfurt . In return, the Prime Minister presented the Prussian ideas for federal reform. As before, they aimed for equal rights for Austria and Prussia. What was new, however, was the demand for “national representation resulting from the direct participation of the whole nation”. This was nothing more and nothing less than an offer of alliance by Prussia to the national movement, which was closely linked to liberalism. In the short term, this was of no use to Bismarck, as he was out of the question as a partner for the liberals in view of the constitutional conflict. The opposition in Prussia was able to maintain its position in the new elections at the end of October 1863.

German-Danish War

The question of federal reform was soon masked by a crisis of international magnitude. After the death of Frederick VII of Denmark , a dispute broke out over the future of the two duchies of Schleswig and Holstein . Schleswig was a fiefdom of Denmark, while Holstein was a member of the German Confederation . However, both territories were subject to the Danish king in personal union ( Danish state as a whole ). Friedrich von Augustenburg claimed the lands for himself. The German national movement supported him and called for the unification of the two duchies and their incorporation into the German Confederation as an independent state. The new Danish King Christian IX. , who was under pressure from the national movement in his own country, reluctantly signed the November Constitution instead , which bound Schleswig closer to Denmark in constitutional terms than Holstein and thus violated the provisions of the London Protocol on the existence of the state as a whole.

To the disappointment of the national and liberal movement, Bismarck refused to support Friedrich von Augustenburg's claim. At the same time, however, he turned against the Danish position and sought in the medium term to integrate the two duchies into the Prussian sphere of influence. At the time of the crisis, however, this was not enforceable in terms of foreign policy. That is why Bismarck, like Austria, initially had an interest in a new Augustenburg state. The Austrians saw a "national solution" to the Schleswig-Holstein question as a threat to their own multi-ethnic state. Against this background, the two German great powers could once again work together.

As on other occasions, Bismarck's policy in the Schleswig-Holstein crisis did not follow a fixed plan. Rather, he assumed that the circumstances would most favor those who let themselves be guided by them, wrested solutions from them and did not try to impose them on them.

Bismarck initially appeared as a defender of the existing international law and asked Denmark to return to the soil of the London Treaties of 1852 . In doing so, he calmed the major European powers. Austria sided with Prussia. The other German states in the German Confederation and the Bundestag were largely marginalized as a result. In fact, Bismarck and the Austrian envoy Alajos Károlyi declared in Berlin that both great powers claim the right to disregard the decisions of the Bundestag. This was the first time that Prussia and Austria jointly called into question the continued existence of the Confederation.

The conflict over Schleswig and Holstein first led to a federal execution against Holstein and Lauenburg in December 1863 and then - against the protests of the German Confederation - in February 1864 to the German-Danish war between Prussia and Austria on the one hand and Denmark on the other. In contrast to earlier Prussian wars, the actual leadership did not lie with the king or the high military, but with the prime minister, whose political calculations were subordinated to military steps. When the reports of ill-considered orders from the 80-year-old Commander-in-Chief General Friedrich von Wrangel piled up and he had applied to the king to recognize Schleswig-Holstein as an independent duchy , he was replaced at the instigation of Bismarck.

After Prussia's victory at the Düppeler Schanzen on April 18, 1864, the first negotiations on the settlement of the conflict took place at the London Conference , which failed not least because of Bismarck's tactics. The war continued and the allied Austrians and Prussians conquered Jutland . With that Denmark was defeated. The war ended with the Vienna Peace Treaty of October 30, 1864. In this, Denmark renounced the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg. The temporary considerations of forming a federal state of their own among the Augustenburgers remained fruitless because Bismarck tried to turn such a federal state into a kind of Prussian protectorate. Instead, the duchies were jointly administered by Austria and Prussia . For Bismarck, this construction was only a temporary solution. Not least because of his goal of sole control over the duchies, the Prussian-Austrian antagonism emerged again.

Domestically, the success in Denmark did not cause the Progress Party to give in in the Prussian parliament. The Liberals were now on the defensive against Bismarck with various motions. B. rejected the expansion of the navy because of the constitutional dispute, which was objectively wanted by the majority. In the liberal movement, former critics of the Prime Minister such as Heinrich von Treitschke began to change their position. The liberals began to split into two camps: those who clung to the link between national unification and political liberalization, and those who pursued the first goal while neglecting the second.

German war

After the German-Danish War, Bismarck played seriously for some time with the idea of a Prussian-Austrian agreement under a conservative auspices. When it became clear that the Austrian policy towards Germany determined by Ludwig von Biegeleben did not allow an expansion of Prussian power, Bismarck opted for an alliance with the liberal and national movement with the aim of creating a small German state . However, he by no means steered towards a military conflict from the start. Rather, he initially kept all options open with the aim of sole control over Schleswig and Holstein. In the Gastein Convention in August 1865 it was divided. Holstein was administered by Austria and Schleswig by Prussian. The Duchy of Saxony-Lauenburg came to Prussia. In gratitude, Bismarck received the Prussian title of count. For him, however, the conflict with Austria was only postponed.

Bismarck ultimately decided to go to war because he hoped to end the Prussian constitutional conflict, as a split in the opposition camp was becoming more and more apparent. The main course was set at a meeting of the Privy Council on February 28, 1866. Bismarck succeeded in convincing the king, who was afraid of a "fratricidal war", of the war policy, and he managed to prevent Wilhelm I from changing his mind in the following months.

Bismarck then did everything possible to isolate and provoke Austria. However, he also kept the possibility open of breaking off the course of confrontation should there be excessive resistance from the great powers. With success Bismarck held especially Napoleon III. adopt a neutral stance. Bismarck secured the support of Italy through a fixed-term alliance treaty (April 8, 1866). After he brought the election of a directly elected German parliament into play again in order to provoke Austria, he triggered massive criticism in the Prussian conservative camp. Even Ludwig von Gerlach distanced himself sharply from him. The Liberals continued to regard Bismarck as implausible and did not accept his offer of an alliance. A German civil war was also extremely unpopular with the public. To avert the war, Ferdinand Cohen-Blind even carried out a pistol attack on Bismarck on the afternoon of Monday, May 7th, 1866 after 5 p.m., but survived it.

When Austria transferred the decision on the future of Schleswig-Holstein to the Bundestag on June 1, 1866 , Bismarck allowed the Prussian army to march into Holstein, arguing that this was a violation of the Gastein Convention. Therefore , on June 14th, at the request of Austria , the Bundestag decided to mobilize the armed forces . Prussia then declared the federal government to be dissolved, as such a resolution was inadmissible. It began on June 16, 1866 with the military operations against the kingdoms of Hanover , Saxony and against Kurhessen . A success of the Prussian army seemed by no means certain. Most of the contemporaries, including Napoleon III, expected an Austrian victory. Bismarck put everything on one card. “If we are beaten […] I will not return here. I'll fall in the last attack. "

Bismarck endeavored to keep the war under control himself. This was in contrast to the plans of Chief of Staff Moltke, who planned an unlimited war. The danger that the military might evade political leadership did not come into play because of the shortness of the campaign. For various reasons - such as the division of the armed forces of the German Confederation, the strategic use of the railroad and new tactics on the battlefield - the Prussian army proved to be superior and won the decisive victory in the Battle of Königgrätz on July 3, 1866 .

While Wilhelm I and the military pushed for Vienna to be conquered and harsh peace conditions to be imposed on Austria, Bismarck enforced moderate conditions, assuming that a weakened Austria would be forced to form an alliance with France, which would have led to a two-front war against Prussia be able. In the Peace of Prague of August 23, 1866, Austria did not have to cede any territories to Prussia , but had to agree to the cession of Veneto to Italy, the dissolution of the German Confederation and the formation of a North German Confederation under Prussian leadership. Schleswig and Holstein were annexed by Prussia as well as Hanover, Kurhessen, Nassau and the Free City of Frankfurt . The southern German states initially remained independent.

In 1867, Bismarck acquired the Varzin manor from the endowment of 400,000 thalers that had been granted to him because of the successful German War . He had the Hammermühle paper mill built on its land , which would soon develop into the largest company in East Pomerania, as well as other paper mills. He sold the Kniephof estate to his nephew Philipp von Bismarck in 1868 .

Almost at the same time, he was appointed commander of honor of the traditional Order of St. John in 1868 .

End of the Prussian constitutional conflict

The war meant, among other things, that the conservatives were able to considerably expand their position in the Prussian state parliament. In order to finally settle the conflict with the liberals, Bismarck had it announced that he wanted to ask the state parliament for “ indemnity ”, that is, for the subsequent approval of the expenditure. This meant the admission that in the years since 1862 he had effectively governed without a legitimate budget. Bismarck did not want this to be seen as an admission of guilt. According to the historian Heinrich August Winkler , the government's position was constitutionally untenable.

Nevertheless, there was a change in policy that no one had expected. The question of how to judge Bismarck's offer led to a split in the liberals. While some argued that further progress on the national question could be expected from Bismarck, others believed that liberal civil liberties should take precedence over national unity. This conflict led to the separation of the moderate and national liberals from the Progressive Party and the formation of the National Liberal Party . Similar changes took place in the Conservative camp. From the ideologically influenced old conservatives around Leopold von Gerlach, who had already turned away from Bismarck before the war of 1866, now politically minded Bismarck supporters separated and formed the Free Conservative Party . In the years that followed, Bismarck was able to rely on national liberals and free conservatives for his policy.

Reform work

The victory in the German War brought about a change in the opinion of Bismarck in the German and Prussian public. With the annexations, Bismarck did not concern himself with the principle of monarchical legitimacy, which is central to the conservatives . The Reichstag of the new North German Confederation was elected according to democratic principles. The central aspects of the federal constitution were largely determined by Bismarck himself ("Putbuser dictates"), although he also had to agree to some compromises in the parliamentary deliberations. The constitution, which in essence continued to apply during the German Empire, is therefore also called the Bismarckian Reich constitution .

Together with the position of the Prussian Prime Minister and the office of Foreign Minister, Bismarck now held an extremely strong position of power as the North German Chancellor. In the constituent Reichstag (February to April 1867) it was decided that, according to the constitution, neither the chancellor nor other members of the government could be brought down by the Reichstag - a constitutional situation that is not unusual in Europe. All in all, Bismarck was very accommodating to the liberal demands, ultimately implementing reforms that were common at the time and could hardly be prevented in a modern state.

The internal changes went far beyond the constitution anyway. They included the general legal system, the economic and social constitution and the administrative structure. Despite all the shortcomings (which were typical of the period), it is noteworthy that under the responsibility of Bismarck, who a short time previously had been generally considered to be an arch-conservative, a state system that was very modern for the time emerged. In many areas this corresponded to liberal ideas. The actual implementation was in other hands. Rudolph von Delbrück in particular was a formative personality here. Nevertheless, Bismarck's personal influence should not be underestimated. The historian Lothar Gall sees the final implementation of the modern, bureaucratic, centralized institutional state in Central Europe with the legal forms and institutions that are important for the development of industrial society as essentially Bismarck's work.

Franco-Prussian War and the establishment of an empire

The way to war

In continuation of his functional relationship to the national idea, the nation became important for Bismarck as an integration factor after 1866. Bismarck recognized that the monarchy and the associated state could only survive in the long run if Prussia placed itself at the head of the national movement. At the same time, for reasons of power politics, he endeavored to unite the southern German states with the North German Confederation. His goal now was the creation of a small German nation state under Prussian leadership.

Protective and defensive alliances were concluded with the southern German states , but the North German Confederation did not turn out to be the magnet Bismarck had hoped for and which led to the annexation of the distant German states. The elections for the customs parliament won opponents of union in Bavaria and Württemberg .

Bismarck was of the opinion that only an external threat could change the mood in his mind. However, he did not try to create a specific threat situation himself. Although he considered it likely that German unification had to be promoted by force, “an arbitrary intervention in the development of history, determined only on the basis of subjective reasons, has only ever resulted in the chopping off of unripe fruits; and in my opinion it is obvious that German unity is not ripe at this moment ”.

In terms of foreign policy, Bismarck reckoned on the part of France that there would be the strongest resistance to a German nation-state. In the French public, territorial demands were made under the slogan “ Vengeance for Sadowa ” (Königgrätz), which led to the Luxembourg crisis. With the neutralization of Luxembourg in May 1867, the problem was solved. Bismarck used the opportunity to reinforce the anti-French mood through parliamentary speeches and press articles . Napoleon III saw the outcome of the conflict as a defeat and then did everything possible to suppress further Prussian ambitions. It is unclear whether Bismarck was actually ready to accept the acquisition of Luxembourg by France, and only the circumstances prevented this, or whether the outcome of the crisis arose from his conscious calculation. Regardless of this, the North German Confederation and France now faced each other in all sharpness.

Another conflict with France arose in early 1870 over the question of the Spanish succession to the throne . Bismarck urged Prince Leopold von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen to run for office. The prince came from the Catholic line of the Hohenzollern rulers in Prussia, which is what Napoleon III believed him. made unacceptable. At first, Bismarck was only concerned with achieving a diplomatic victory while keeping several options open. Both Bismarck and Emperor Napoleon III. wanted to prevent a loss of reputation for themselves, so that the diplomatic conflict escalated into a national question.

In France, the Hohenzollern candidacy had the effect Bismarck had hoped for, as there was fear of being encircled by Hohenzollern states in the future. The prince's resignation initially seemed to defuse the crisis. Wilhelm I, however, rejected France's request that he should renounce similar candidacies for all future in the name of the House of Hohenzollern. The king informed Bismarck about this in the so-called Emser Depesche . The latter took the opportunity and described Wilhelm's encounter with the French ambassador as particularly harsh in a press release. Napoleon III. had been snubbed before the whole world. Given the reactions in the French public, he saw no choice but to declare war on Prussia. With this, France, as intended by Bismarck, appeared as the aggressor . In Germany public opinion was now wholly on the side of Prussia, and the southern German states took the fall of the alliance for granted. In contrast, France was completely isolated in terms of foreign policy.

War and the founding of an empire

The Franco-Prussian War initially seemed to bring about a quick decision, following the usual pattern. As a result of the capture of Napoleon III. the Second Empire collapsed at the Battle of Sedan . However, a quick peace was not reached because the German side, with Bismarck in a leading role, made the cession of Alsace-Lorraine a condition. This territorial demand was also made under the influence of public opinion in Germany. In the short term, this meant that the newly formed French government not only continued the war, but even elevated it to a national people's war. In the long term, Franco-German relations were severely strained by the Alsace-Lorraine question. The permanent weakening of France developed into a central goal of Bismarck's foreign policy.

The Prime Minister repeatedly interfered in the decisions of the military during the war. This led to violent conflicts with the military leadership, which culminated on the question of a siege or bombardment of Paris . Here Bismarck prevailed with his demand for a bombardment.

The war had put the opponents of German unification on the defensive in southern Germany as well. From mid-October 1870, Bismarck negotiated in Versailles with the delegations of the southern German states. Last but not least, an alliance of German princes and free cities was intended to counter more far-reaching ideas of the national and liberal camp. During the negotiations, Bismarck avoided direct pressure and instead argued with the advantages of such a merger. Overall, he put his ideas through.

Baden and Hessen-Darmstadt were the first to declare their accession to the North German Confederation. Württemberg and Bavaria paved the way for the establishment of the German Empire after they had been granted reservation rights. Bismarck himself wrote the “ Kaiserbrief ”, with which Ludwig II of Bavaria asked Wilhelm I to accept the imperial crown. In this context, Bismarck also bribed Ludwig with funds from the Welfenfonds . However, it was only with difficulty that he succeeded in persuading King Wilhelm, who feared that the Prussian monarchy would lose importance, to accept the title of emperor.

On January 18, 1871, the “Imperial Proclamation” took place in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles . It marked the foundation of the German Empire . A few days later Paris capitulated. The Franco-Prussian War ended on May 10, 1871 with the Peace of Frankfurt . On June 16, 1871, he and the Kaiser took part in the brilliant Berlin Victory Parade .

Bismarck had thus reached the climax of his political career. He was raised to the rank of prince and Wilhelm I gave him the Sachsenwald near Hamburg as a gift. Bismarck was now one of the great landowners in the empire and, thanks in part to the skillful administration of his funds by Gerson Bleichröder , was a wealthy man. He earned most of his fortune by selling the wood from the Sachsenwald. Between 1878 and 1886, his main customer, Friedrich Vohwinkel , bought wood worth more than one million marks from Bismarck's forests. Bismarck acquired a former hotel in Friedrichsruh in the Sachsenwald and had it converted. After 1871 Friedrichsruh became the focus of his private life.

Chancellor

The new empire largely adopted the constitution of the North German Confederation. As Reich Chancellor , Chairman of the Federal Council, Prussian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, Bismarck remained the dominant politician. In addition, he was able to build on his immense prestige as the founder of the empire. This weighed heavily against Wilhelm I, so that Bismarck was mostly able to get his way through with the German Kaiser . Wilhelm therefore complained: "It is not easy to be emperor under such a chancellor."

Family and way of life

As much as Bismarck was permeated with a passion for politics and a love of power, he also longed for a release from this burden. As early as 1872 he complained: "My oil has been used up, I can no longer." During the years of his chancellorship, Bismarck was not only psychologically stressed, but also physically badly damaged. More and more often he had to withdraw to his estates, sometimes for months. Bismarck drank and ate in abundance. He got bigger and bigger; In 1879 he weighed 247 pounds (124 kilograms) and was 1.90 meters tall. He suffered from numerous sometimes chronic diseases such as rheumatism , phlebitis, digestive disorders, hemorrhoids and above all from insomnia, caused by gluttony . In addition to consuming alcohol and tobacco, contemporaries such as Baroness Hildegard von Spitzemberg also reported taking morphine . Only Ernst Schweninger , his new doctor, was able to persuade him to adopt a healthy lifestyle in the 1880s. He previously suffered from facial neuralgia, which is why he grew a full beard before Schweninger's treatment so that he did not have to shave.

The family played a major role in Bismarck's private life. But also in this area he always got his way. When his son Herbert von Bismarck wanted to marry the divorced Princess Elisabeth zu Carolath-Beuthen in 1881 - a Catholic who was related to and related by marriage to numerous Bismarck opponents, such as Countess Marie Schleinitz - Bismarck ultimately prevented this by only giving him disinheritance, then threatened suicide. Herbert complied, but has been a bitter man ever since.

Foreign policy

The founding of the German Empire fundamentally changed the European balance of power. The new empire was initially outside the pentarchy that had developed over the past hundred years, as it had a completely different power-political quality than the very small Prussia. Therefore, the empire was seen as a troublemaker of the international order. After a long learning process, Bismarck realized that the general mistrust of the other states towards Germany could only be reduced by self-restraint and the renouncement of further territorial gains. He therefore assured that the empire was saturated . "We are not pursuing a power policy, but a security policy," he affirmed in 1874.

One of the basic aims of Bismarck's foreign policy was to weaken France. In order to achieve this, he tried to establish good relations with Austria and Russia, without preferring either side. The result of this strategy was the Three Emperor Agreement of 1873. How difficult it was for the German Empire to consolidate its new position at the expense of France, however, was shown in 1875 by the " war-in-sight crisis " largely provoked by Bismarck himself . Bismarck's attempt to implement a German hegemonic policy against France failed.

Even if Bismarck only wanted to threaten the resurgent France and did not specifically plan a war, the crisis was instructive for him. It showed that rapprochement between France and Russia could not be ruled out in principle. The possibility of an alliance between the two worried him for the remainder of his term in office. But England had also made it clear that it would not accept a further increase in Germany's power. In case of doubt, the European wing powers worked together to prevent a disturbance of the power-political equilibrium.

Bismarckian alliance system

Especially from the war-in-sight crisis, Bismarck drew the conclusion that a defensive policy was the only realistic alternative for the Reich. Due to its location in the center of Europe, the empire threatened to be drawn into a great European war. Against this background, Bismarck developed a diplomatic concept aimed at shifting the tensions between the great powers to the periphery in order to save the center of Europe from wars. This concept first came to fruition during the Balkan crisis between 1875 and 1878. Bismarck encouraged tensions between the powers, but at the same time prevented the conflicts from spiraling out of control. He summarized his foreign policy strategy in 1877 in the Kissinger Dictation . In doing so, he proceeded from "an overall political situation in which all powers except France need us, and where possible are deterred from coalitions against us through their relationships with one another."

During the Berlin Congress to end the Balkan crisis in 1878, Bismarck presented himself as an “honest broker”. Although this strengthened his foreign policy prestige abroad, the limits of his concept were immediately apparent. Tsar Alexander II blamed Bismarck for ensuring that Russia's successes remained very limited. This led to Bismarck pushing for cooperation with Austria. This in turn resulted in the two- alliance treaty of 1879. This defensive alliance against Russia became a permanent alliance that was to shape foreign policy throughout the empire. Bismarck himself stylized the connection as a kind of contemporary new edition of the German Confederation and as a “bulwark of peace for many years. Popular with all parties, exclusive nihilists and socialists. "

Bismarck also succeeded in relieving tensions between Germany and Russia and in 1881 concluded the three emperor alliance. This initially prevented close ties between Russia and France. The alliance system was supplemented in 1882 by the Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, and in 1883 by the annexation of Romania to the Dual Alliance .

Imperialist episode

In the mid-1880s, Bismarck seemed to have successfully completed the diplomatic safeguarding of the empire. The concept of saturation, however, was increasingly called into question by the imperialist tendencies of the time. Bismarck himself was actually an opponent of colonial acquisitions.

In Germany, too, an imperialist movement emerged that pushed for the acquisition of German colonies . Bismarck could not escape the pressure of this in the long run. Which domestic and foreign policy reasons led to a change of heart on the part of the Chancellor is still controversial today. The upcoming Reichstag elections are mentioned , the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce's insistence on protection of the Reich for its trade interests in West Africa, the social-imperialist strategy of diverting attention from the domestic political problems of the Empire, the attempt to drive a wedge between Great Britain and the England-friendly Crown Prince, whose accession to the throne he feared, and securing the global balance of power . In 1884 Bismarck finally seemed to be convinced that a successful colonial policy contained more opportunities than risks.

In 1884 and 1885 several territories in Africa and the Pacific were acquired. However, as the domestic political constellations in France and Great Britain changed, Bismarck quickly lost interest in German colonial policy. At first it remained an episode. In 1888 Bismarck told the colonial advocate Eugen Wolf : “Your map of Africa is very nice, but my map of Africa is in Europe. France is on the left, Russia is on the right, we are in the middle. This is my map of Africa. ”However, Bismarck had unintentionally released forces that could no longer be controlled during the Wilhelmine era.

Crisis of the alliance system

In the second half of the 1880s, Bismarck's foreign policy system was increasingly threatened. From 1886 the revanchist tendencies increased in France. At times there was a threat of a Franco-Russian alliance and with it the danger of a two-front war for the German Reich. Bismarck, however, exaggerated the crisis with France in order to be able to implement his domestic political plans to reinforce the army.

A new Balkan crisis arose almost at the same time. Bismarck tried in vain to balance the tensions between the two opponents Austria and Russia. The three emperor alliance broke up. In Russia, as a result, the votes for an alliance with France continued to increase. Problems caused by Bismarck's protective tariff policy exacerbated the situation. In Germany, influential figures from the military and diplomacy such as Friedrich von Holstein , Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke and Alfred von Waldersee pleaded for a preventive war against Russia. Bismarck strictly rejected such ideas. He continued to think the war was avoidable. As a power and real politician, nationalist and social Darwinist ideas played no role for him.

Bismarck's old alliance system was broken, but he was able to defuse the crisis again. In the Balkans he refused to "get the chestnuts out of the fire for England and Austria." Without breaking with Austria, he managed to prevent an open war. In February 1887, Bismarck was involved in the background in bringing about the Mediterranean Entente between Great Britain, Austria and Italy. Its aim was to limit the Russian urge to expand. A short time later, Bismarck concluded the reinsurance treaty with Russia in order to tie Russia to Germany again.

Domestic politics

The liberal era and the Kulturkampf

As in the time of the North German Confederation, the domestic policy of the German Reich was based in the first few years on Bismarck's cooperation with the Free Conservatives and the National Liberals. These exerted a considerable influence on the standardization, design and modernization of the economic and legal system, both in the Reich and partly in Prussia. At times, Bismarck did not shy away from a conflict with the conservatives. When the Prussian mansion refused to approve a reform of the district order in 1872, Bismarck prompted Wilhelm I to appoint additional mansion members in order to get the law through with the help of this " pair push ". There was great outrage among the conservatives, and Roon even spoke of a coup. This led to Bismarck's resignation from the post of Prussian Prime Minister in favor of Roons. However, since he was not up to the office, Bismarck took it over again after a short time.

The first limits of Bismarck's cooperation with the liberals soon became apparent in various fields. The most important point of contention from 1873 onwards was the area of military organization, over which there were violent disputes. The National Liberals could not agree to the factual waiver of parliamentary control of the military budget ("Äternat") demanded by Bismarck. A compromise proposal by Johannes Miquel came up with a solution in 1874 . Thereafter, the expenditure was approved for seven years each (" Septennat "). Despite this relative success, Bismarck had made the liberals aware of the limits of his willingness to cooperate, even though they de facto gave him eight years of freedom of action. At the same time, the agreement in principle with parliament strengthened Bismarck's position vis-à-vis the military.

National Liberals and Bismarck agreed in their opposition to a Catholic party. For Bismarck, it also played a role that the Center Party, founded in 1870, was a Catholic party that was essentially conservative and withdrawn from his influence. The center created a link between the Catholic workforce, dignitaries and the church. Bismarck consequently reduced it to the ultramontanism he feared . In fact, in the first Reichstag elections in 1871 , the center immediately became the second strongest force. Thus the electoral success of the National Liberals fell, especially in the Catholic-bourgeois camp. For Bismarck, the Kulturkampf had mainly political reasons, but he saw Ludwig Windthorst , the outstanding politician of the Center Party, as a personal opponent: “Two things preserve and beautify my life, my wife and Windthorst. One is there for love, the other for hate. "

Bismarck stylized the Catholics as enemies of the Reich - also to counter rising criticism of his administration. From 1872 various special laws against the Catholics were passed and repeatedly tightened as part of the so-called Kulturkampf . In the course of this dispute, the rights and power of the church were curtailed by imperial and Prussian state laws ( pulpit paragraph , bread basket law ), but civil marriage was also introduced. In this context, Bismarck said to the Reichstag on May 14, 1872: " Don't worry , we're not going to Kanossa , either physically or mentally."

The first, hard stage of the Kulturkampf ended in 1878. In that year Pius IX died. , his successor Leo XIII. signaled a willingness to communicate, which Bismarck was keen on in order to disembark the center. Negotiating directly with the Holy See harmed the party and diminished its reputation among the Catholic population. In addition, the Chancellor had not achieved what he had planned. The Catholic base and the Catholic party did not allow themselves to be divided; rather, the state attacks promoted the formation of a Catholic milieu . In addition, the Catholic press supported the party, which increasingly won seats in the Reichstag. A final reason for Bismarck arose from the break with the National Liberals that had ultimately taken place. He explored the possibility of integrating the center into his politics and thus forming a “blue-black coalition” with the conservatives.

The Kulturkampf ended in April 1887 with the second peace law. Until then, both sides contributed to the de-escalation. Civil marriage and state schools are a consequence of the Kulturkampf to this day. It was not unimportant for Bismarck's future policy that Windthorst was by no means an ultramontane zealot. He was critical of Prussia, but also pragmatic and constitutional, which opened up new political options for Bismarck.

Chancellor crisis and political change

The basis of Bismarck's cooperation with the Liberals grew weaker and weaker. With the start of the crisis , numerous large landowners and industrialists began to raise demands for protective tariffs. Bismarck hoped that economic policy would split the Liberals. Although he did not speak publicly on the matter, he encouraged the stakeholders to split, which was carried out. Bismarck saw a possible ally in the newly founded German Conservative Party ; the party program was coordinated with him personally. The resignation of Rudolph von Delbrück from the office of President of the Reich Chancellery in 1876 became a sign of the looming conflict with the Liberals . Delbrück had been seen as the embodiment of Bismarck's cooperation with the liberals and as the main representative of economic liberalism.

In view of the expected imminent change to the throne, the Liberals represented a danger for Bismarck. Under an emperor Friedrich III. the change to a liberal government was to be expected - along the lines of the British government under Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone . In 1877, Bismarck tried to eliminate Albrecht von Stosch , the chief of the navy, as he was considered to be the future emperor's chancellor. When this failed, Bismarck threatened to resign and temporarily withdrew to his estate in Varzin. The attempt to win over the National Liberals from there with offers - such as a ministerial office for Rudolf von Bennigsen - and concessions for his policy was unsuccessful. He was presented with counterclaims that ran counter to his plans to curb parliamentarism. Thereupon he decided to break with the National Liberals.

With the demand of the National Liberals to reorganize the Imperial Constitution in a more parliamentary sense, a limit had been reached that Bismarck was not prepared to cross. In the Reichstag he declared in 1879: "A parliamentary group can very well support the government and gain influence over it, but if it wants to govern the government, then it forces the government to react against it." In view of the mutual political blockade saw Bismarck forced himself to flee forward. In a speech in the Reichstag on February 22, 1878, he announced a change of course in domestic politics. The goal of a state tobacco monopoly, which he indicated, contradicted central economic principles. Beyond the specific occasion, the members of the government, who are close to liberalism, saw this as a first step towards a fundamentally changed economic policy. Heinrich Achenbach and Otto Camphausen resigned from their offices.

Socialist law and protective tariff

Since August Bebel's speech in the Reichstag on May 25, 1871 in favor of the Paris Commune , Bismarck saw the Social Democrats as a revolutionary threat. Even then he outlined his future policy as follows: “1. Compromise against the wishes of the working classes, 2. Inhibition of agitation that is dangerous to the state through prohibition and penal laws. "

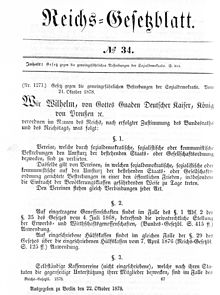

In Bismarck's view, the social repercussions of the founder crisis increased the revolutionary danger. Two assassinations on Kaiser Wilhelm I in 1878 gave Bismarck a welcome opportunity to take action against the Socialist Workers' Party with a socialist law . He wanted to "wage a war of extermination through bills that would affect social democratic associations, assemblies, the press, freedom of movement (through the possibility of expulsion and internment) [...]."

In addition to the fight against social democracy, the attacks also offered Bismarck the opportunity to go on the political offensive again in the face of a lack of parliamentary support and to gain new majorities. A first draft law failed because of the overwhelming majority in the Reichstag. After the second attack, Bismarck had parliament dissolved. He wanted to regain the support of the National Liberals and, moreover, move the base of government further to the right. After the election, the two conservative parties together were stronger than the National Liberals.

In the new Reichstag, after a few concessions, the National Liberals also finally approved the Socialist Law. It remained in force until 1890, extended several times by Parliament. This exceptional law forbade socialist agitation, while the political work of the social democratic parliamentarians remained unaffected. Ultimately, the law failed to serve its purpose and inadvertently contributed to the consolidation of a socialist milieu, because it was only now that Marxist theory really took hold. It is noteworthy that Bismarck later devoted not a single word in his thoughts and memories to the subject .

Against the background of the economic crisis, calls from large landowners and heavy industrialists for protective tariffs grew louder in 1878. When a majority in the Reichstag emerged in favor of this demand, Bismarck, who was hoping for increased state income, also spoke in the so-called “Christmas letter” of December 15, 1878, in favor of a combination of tax reform and protective tariff policy. In the end, only a few National Liberals agreed to this. Instead, Bismarck relied on the German Conservative Party, the Free Conservatives and the Center. The liberal era was over. Bismarck now emphasized the importance of the authoritarian state as a guarantor of national unity and relied on a national-conservative collection movement including the center. However, this party constellation did not offer a solid parliamentary basis, as had previously been provided by the National Liberals. Many of Bismarck's political initiatives were therefore unsuccessful in the years that followed.

The transition from free trade to protectionism took place in several steps in the years that followed. Bismarck hoped to be able to make political capital from his response to the wishes of the connection between “rye and iron” in order to expand the conservative base of the empire and to consolidate his own position.

Social legislation and coup plans

In view of his difficult parliamentary situation, Bismarck tried to reduce the previous importance of the parties. The field of dispute should be social and economic policy. Therefore, in 1880, he himself took over the office of Minister of Commerce , which he held until 1890. In order to influence the economic legislation , he tried to establish an economics council made up of representatives of the business associations, with which the parliament should be bypassed. However, this failed due to the resistance of the parties.

The main aim of Bismarck's social policy was to create stronger ties to the state. The parties should be separated from their base. Bismarck by no means obscured his actual goal of maintaining power. Initially, only accident insurance was planned , later insurances against illness , disability and old-age poverty were added. These should largely be controlled by the state - at times Bismarck even spoke of state socialism . He wanted to "create in the great mass of the dispossessed the conservative attitude that brings with it the feeling of entitlement to a pension."

"My idea was to win over the working classes, or should I say to bribe them, to see the state as a social institution that exists because of them and wants to look after their well-being"