Fraternity

Fraternities are a traditional form of student union . Today you can find them at universities in Germany , Austria , Switzerland and Chile . Almost all fraternities are committed to the principles of the original fraternity of 1815, although the content varies greatly. The term “Burschenschaft” is used today by some very different student associations.

overview

Etymology and usage

The word "fraternity" means something like "totality of boys". The word boy is derived from the neo-Latin bursarius , the resident of a Burse , and was a general term for students in the 18th and early 19th centuries . There is evidence from this period in which the word “fraternity” is used synonymously with the word student body . This was still the case at the Wartburg Festival in 1817, two years after the founding of the original fraternity in Jena. This original fraternity considered itself to be an amalgamation of all students, with the abolition of the then common country union amalgamations . It was only later, when it became clear that this general claim could not be enforced, that “fraternity” became a name for a certain type of student association that existed alongside various others.

The members of a fraternity are called fraternity members or fraternity members . Sometimes referred to as pejorative perceived fraternity l he is often generalized to Korporierte total respect, as is occasionally used by negative with respect to the fraternity set students "Burschi" ( see also: Burschi reader ). Other corporates, especially corps students , often use the casual designation Buxe .

Similarities of the fraternities

Almost all student associations calling themselves fraternity have in common the commitment to the principles of the original fraternity of 1815, although the interpretation of these principles is by no means uniform. As a reaction to the Congress of Vienna, the urban ideals were the totality of all students, the Christianum and the patriotic ideals (Unified Germany, liberation from the authoritarian regime).

All fraternities today are colored , which means that their members wear a ribbon in the colors of the association and a student cap , the so-called Couleur , at official events . The traditional colors of the fraternity are black-red-gold , as they were already used by the original fraternity . Even today they are the colors of a large part of the fraternities.

The majority of today's Fraternities is striking , that depends scales from other striking student associations. However, the scale is partially free. Unsuccessful fraternities are in the minority. They mostly reject the scale length for Christian reasons.

Classification within the student associations

Although only about 300 of the 1500 to 2200 student associations in the German-speaking area call themselves “Burschenschaft”, the term is often incorrectly used in public as an umbrella term for all student associations . Most other student corporations, such as Catholic student associations , country teams or corps , have historically no connection to the origin of the fraternities and also have a different orientation today.

Fraternities are political student associations and deal with political issues out of responsibility for society. In the public today fraternities are often perceived as politically right-wing or even right-wing radical .

history

The original fraternity

The “general fraternities” emerged as assemblies of (male only) students at German universities after the wars of liberation , which decisively shaped the student culture in Germany. Historians estimate that every second or third student took part in the wars as a war volunteer . Although only about five percent of the total number of war volunteers could be considered as students, there was no social group with such a high proportion of volunteers. Many students had fought in the Lützow Freikorps , among others , which was not only recruited from Prussian subjects, but also from volunteers from all over Germany. Returning to the universities from the Wars of Liberation, they campaigned for the abolition of small German states and the creation of an all-German empire under a constitutional monarchy during the period of the Restoration and the Congress of Vienna .

The original fraternity was founded in Jena on June 12, 1815. The national associations dissolved their senior citizens' convention (SC). For this purpose, the members of the four country teams Thuringia, Vandalia, Franconia and Curonia moved to the Gasthaus Grüne Tanne . This place was outside the city limits of Jena and was therefore beyond the jurisdiction of the university. As a sign of dissolution, the country teams lowered their flags there. 30 public officials were elected from among the 143 founders present. Karl Horn , the last senior at Vandalia, was appointed the first speaker . This brought the fraternity into being.

The original fraternity consisted of groups with national, Christian and liberal ideas. Her intellectual pioneers included Ernst Moritz Arndt , Friedrich Ludwig Jahn and Johann Gottlieb Fichte . With the values of honor, freedom, fatherland, she demanded civic responsibility, ethnic solidarity and individual rights at the same time. This synthesis of different elements was made possible by the elitist approach, which primarily emphasized the individual's duty to stand up for the whole.

The constitutional document of the Jena fraternity of June 12, 1815 states:

“ Raised by the thought of a common fatherland, imbued with the sacred duty that is incumbent on every German to work towards the revival of the German way and spirit, thereby awakening German strength and discipline, and thus to reestablish the previous honor and glory of our people and to protect against the most terrible of all dangers, against foreign subjugation and compulsion to despotism, some of the students in Jena have met and talked about establishing a union under the name of a fraternity. "

The Wartburg Festival

The patriotic idea was an idea that attracted a great number of students. To tell this mind around the world, the Jena invited fraternity representatives of German universities to the Wartburg in Eisenach in order there on October 18, 1817 the 300th anniversary of the thesis stop Martin Luther on 31 October 1517 at the same time the victory over Napoleon in to commemorate the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig from October 16 to 19, 1813. Over 500 students from all over Germany took part in the festival.

Above all, the aim of uniting the student body in a uniform organization was formulated here in order to anticipate the unity of Germany in the university sector. The Isis or Encyclopädische Zeitung magazine quoted some speakers at the Wartburg Festival in 1817:

“That is precisely why you do not have to give yourself names that contradict this universality. You don't have to call yourself white, black, red, blue, etc. because there are others too; you don't have to call yourself Teutons either; for the others are also Teutons. Your name be what you are alone and exclusively, namely student body or fraternity. This includes all of you and no one else. But be careful not to wear a badge and so sink down to the party that would prove that you do not know that the class of the educated repeats the whole state in itself, and thus its essence is destroyed by fragmentation in parties. "

After further emotionalizing speeches, Hans Ferdinand Maßmann demanded a book burning of writings that were considered reactionary , anti-national or un-German. 26 writings were symbolically handed over to the flames , including works by the writers August von Kotzebue , August Friedrich Wilhelm Crome , Saul Ascher and Karl Leberecht Immermann , as well as the Code Napoléon . Due to the high value of books, however, only waste bundles labeled with their titles were burned. This was nothing unusual at that time, but symbols of foreign and princely rule, such as a lace , a soldier's pigtail and a corporal's stick were burned, which was the real sensation according to the opinion of the time.

In the aftermath of the Wartburg Festival, the expressed thoughts were summarized in a program with the help of Jena professor Heinrich Luden , which the constitutional historian Ernst Rudolf Huber called "the first German party program".

The 35 principles and 12 resolutions can be summarized as follows:

- The political turmoil in Germany should give way to political, religious and economic unity.

- Germany is to become a constitutional monarchy. The ministers should be responsible to the parliament.

- All Germans are equal before the law and have the right to a public trial before a jury according to a German code of law.

- All secret police are to be replaced by the municipal authorities.

- Security of person and property, the abolition of birth privileges and serfdom are just as constitutionally guaranteed as the special promotion of the hitherto oppressed classes.

- General conscription (Landwehr and Landsturm) takes the place of the standing armies.

- Freedom of speech and the press are constitutionally guaranteed.

- Science should serve life, especially the study of morality, politics and history.

- All divisions in the universities should stop, secret leagues should not exist.

- Every boy must renounce all small states and foreigners, all caste and despotism.

The program took up essential liberal ideas of the French Revolution and embedded them in a “patriotic” and “defensive” monarchy . Civil rights can be found today in all European constitutions, including the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany .

In the following year, fraternities were established at many universities to promote these principles. These did not initially see themselves as a large number of independent fraternities, but rather as part of a single large fraternity that should encompass the entire student body and replace all previously existing student associations: the “ General German Burschenschaft ”. The founding of the same was decided at the first Jena Burschentag in 1818 by the representatives of the fraternities from 14 university towns. The still remote connections should be won for the fraternity through conviction.

The goal of uniting all students in this general German fraternity was ultimately not achieved because the movement diversified at the same time as it expanded and the majority of the corps continued to cling to their old traditions. So - at least at the big universities - there were still several corps and soon several fraternities.

Heinrich Heine as a critical contemporary witness

Heinrich Heine studied law in Bonn , Göttingen and Berlin between 1819 and 1825 . In Bonn he joined the fraternity community at the age of 22 and later also attended a fraternity get-together in Göttingen. In February 1821 he was expelled from the fraternity for violating the principle of chastity . The reason for the departure of the Jewish-born Heine from the fraternity was probably an anti-Jewish resolution of the secret Dresden Boys' Day in 1820, in which it was said that Jews were “unable to accept”, “unless it is proven that they are Christian-German want to train for our fatherland. "

While he was still a member of the fraternity in 1820, he was very critical of the Wartburg Festival and his Göttingen experiences:

“In the Wartburg, on the other hand, there was that unrestricted Teutomanism, which greeted a lot about love and faith, but whose love was nothing more than hatred of the stranger and whose faith consisted only in unreason, and which in its ignorance could not invent anything better than books to burn!"

"In the beer cellar in Göttingen I once had to admire the thoroughness with which my old German friends prepared the proscription lists for the day when they would come to power. Anyone who was descended from a French, Jew or Slav in only the 7th member was condemned to exile. Anyone who had written in the least something against Jahn or even against old German ridiculousness could be prepared for death ... "

Heine later became a member of a student union that was subsequently formed into the Corps Hildeso-Guestphalia .

The demagogue persecution

In 1819 the theology student and former fraternity member Karl Ludwig Sand murdered the writer and alleged Russian agent August von Kotzebue , whose work History of the German Empire was symbolically burned at the Wartburg Festival . In the fraternity, Sand was a supporter of the particularly radical wing of the “unconditional”. His assassination offered the governments of the German Confederation, which had gathered for the Bundestag in Karlsbad , a welcome opportunity to impose strict bans on all student organizations.

These bans, known as the Karlsbad Resolutions , were largely due to the influence of the reactionary Austrian State Chancellor, Prince Klemens Wenzel Lothar von Metternich . Because of her, many fraternity members were exposed to state observation and persecution over the next few years. The resolutions stipulated that a “sovereign representative” was to be appointed for each university, who carefully checked on site whether the professors were conveying politically unpleasant ideas to the students. The main body was the Mainz Central Investigation Commission , to which every abnormality had to be reported. Unpopular professors could be expelled from the university and were banned from working in the entire German Confederation .

“The long-standing laws against secret or unauthorized connections in the universities should be upheld in all their strength and severity, and especially extended to the association founded for some years and known under the name of the general fraternity, more definitely than this Association is based on the absolutely inadmissible requirement of an ongoing community and correspondence between the various universities. With regard to this point, the government plenipotentiaries should be obliged to exercise excellent vigilance.

The governments agree that individuals who can be shown to have remained in or entered into secret or unauthorized associations after the announcement of the present resolution shall not be admitted to any public office. "

In 1822 the General German Burschenschaft disintegrated due to the ongoing persecution, but was rebuilt on a smaller scale at the Bamberg Boys' Day in 1827. On this boys' day it was decided to turn away from the Christian principle, so that Jews could now also become members for the first time. Subsequently, the fraternity took over the scale from the corps after the original fraternity had not yet been successful.

Around 1825 the fraternity movement divided more and more into a radical republican and national line that represented political activism ("Germania") and a university-political and freethinking-liberal line that aimed at internalizing fraternity life (" Arminia ") ). In 1829 it finally came to a break: the Armenian fraternities were excluded from the umbrella organization and their right to exist was denied. The terms Germania and Arminia are still the most common fraternity names and can be found in many universities.

The Hambach Festival

After the July Revolution in Paris in 1830, the democracy movement in Germany gained momentum again. Little by little, the prohibitions of the Karlsbad resolutions were relaxed again in many German states. Not so in the Kingdom of Bavaria belonging Palatinate . There, in response to the strict and repressive censorship, the German Press and Fatherland Association was founded in the spring of 1832 , to which numerous fraternity members also belonged. Since political gatherings were forbidden in Bavaria, the association organized a "folk festival" at Hambach Castle .

At the meeting that went down in history as the Hambach Festival from May 27 to 30, 1832 , the approximately 30,000 participants called for freedom, democracy and the unity of Germany. The colors of the fraternity black-red-gold were used here for the first time by non-students and finally became a symbol of the German striving for unity and democracy. In 1848 they became the colors of the German Confederation and later the state flag of the Weimar Republic , the Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR .

At a meeting of leading German democrats and liberals on the second day of the Hambach Festival, representatives of the Germanic fraternities called for the immediate formation of a provisional government and the setting of a date for the start of an armed uprising. However, this was rejected as hopeless by the representatives of the Press and Fatherland Association.

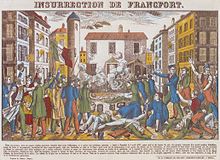

The Frankfurt Wachensturm

It was mainly fraternity members of the Germanic direction from Heidelberg and Würzburg who organized the Frankfurt Wachensturm on April 3, 1833, through which the arms and the treasury of the German Confederation were to be conquered, which should have triggered an armed popular uprising. The failure of this action, in which there were nine dead and 24 injured among the insurgents, represented a serious setback for the entire fraternity movement. Only a few fraternities survived the now rigorously applied prohibitions of the still valid Carlsbad resolutions. The founding dates of most of the fraternities still in existence today are therefore after this date.

The Bundestag set up a commission of inquiry that carried out years of extensive research into the conspirators and their backers. By 1838 it wrote out more than 1,800 people - around two thirds fraternity members - to be searched. Quite a few fraternity members left Germany in their thirties and fled to North America. In the end, 39 people were sentenced to death for high treason , but later pardoned to imprisonment, some of which was life imprisonment.

On January 10, 1837, six of the fraternities sentenced to life imprisonment managed to escape from prison with outside help. The sympathy of the population was on their side. Verses of ridicule were composed against the search measures of the authorities, which are still in student songbooks and are sung regularly.

The Free Republic (around 1837, author unknown)

|

1) |

4) But they came back with swords in hand. |

The progress

After the failure of the Frankfurt Wachensturm, the strict repression measures caused the demise of most of the fraternities. The fraternities that remained or were newly established in secret were small and less political than before. During this time they assimilated themselves to the conservative corps and lost potential members to the newly emerging apolitical student associations such as academic choral societies or scientific associations.

In the 1840s the Progress movement also gained support within the fraternity. The goals of this liberal progress movement in the student body were the equality of all students by abolishing the privileges of the fraternities, the abolition of the academic privileges vis-à-vis the citizenry, and the reform of the universities by abolishing academic jurisdiction and dueling. In the mid-1840s this movement became radicalized and demanded the abolition of the traditional student traditions and special positions. Ultimately, these goals were not achieved. For the fraternity movement, however, the progress meant a renewed strengthening and at the same time diversification through numerous divisions and new foundations.

From the March Revolution to the Unification of the Empire (1848–1870)

The fraternities were a driving force behind the revolution of 1848 . As a result of the establishment of the National Assembly in Frankfurt's Paulskirche , to which up to 163 fraternity members belonged and whose first president Heinrich von Gagern was a fraternity member, the Karlovy Vary bans were finally lifted. The colors of the fraternity black-red-gold were declared German national colors on July 31, 1848. The organizations that were previously persecuted and driven underground have now been transformed into associations of the academic elite . Fraternities and all kinds of student associations increased tremendously.

After the failure of the revolution, however, numerous fraternity members had to leave Germany again and emigrated as part of the so-called Forty-Eighters mainly to the USA - including the later US Interior Minister Carl Schurz - but also to Australia and South America.

After the Karlovy Vary resolutions were repealed, attempts were repeatedly made to found a fraternity umbrella organization . Short-term umbrella organizations were the General Burschenschaft (founded in 1850), the Eisenacher Burschenbund (1864), the Eisenach Convention (1870) and the Eisenach Deputy Convent (1874), but they were never able to unite a majority of the fraternities in themselves dissolved again a few years ago. Several fraternities also came together in the North German cartel for several years in 1855. Initiated by the Eisenacher Burschenbund , local deputy convents were established in the 1860s .

On the occasion of Friedrich Schiller's 100th birthday, fraternities were officially founded in 1859 in the Austrian Empire . Metternich had previously been able to enforce a coalition ban there using efficient methods of repression. Only after the lost battle of Solferino did Emperor Franz Joseph II have to make concessions to the citizens, among other things in the form of more liberal association laws. The medieval nation still existed in Austria-Hungary until 1849 , after the revolution a ten-year vacuum prevailed after it was banned. This has now been compensated for by a wave of student corporations founded. In Austria fraternities, corps, new compatriots and Catholic associations did not arise one after the other and for different reasons, but simultaneously and in parallel in the years 1859–1864. In the multi-ethnic state, however, the fraternity had to struggle with national identity problems and in Austria-Hungary began to develop increasingly towards German nationalism .

The Catholic Church saw in the fraternities and other corporations an increasing danger to morality and faith and punished the Mensur with excommunication . This was followed by the suppression of Catholic students by other corporations - especially in Germany, which was dominated by Prussian Protestants - which is why Catholic student associations were gradually founded on the initiative of the Church and individual pastors , which, without sharing the ideology of the fraternity, almost exactly whose appearance and customs gave.

Fraternities in the German Empire (1871-1918)

After the founding of the empire in 1871, the fraternities in the German Reich - in contrast to those in Austria - saw their most important goal, namely the amalgamation of the German states and states, as achieved. During this time, all student associations aligned themselves with one another, following the example of the corps . For the fraternities this meant above all that duels became a duty. In the initial phase, the fraternity rejected duels. The revolutionary movement became an organization supporting the state. The struggle for unity and freedom often flattened to mere nationalism . However, the political spectrum remained very broad and ranged from radical-democratic to national - conservative to ethnic - anti-Semitic groups. Not so in Austria: German national and radical anti-Semitic politicians like the fraternity member Georg von Schönerer polemicized against the supranationalist and catholic imperial house of the Habsburgs and for an all-German union.

Long-lived fraternity umbrella organizations were founded in the German Empire for the first time: in 1881, the General Deputy Convent was founded in Eisenach by initially exclusively Imperial German fraternities , which from 1902 was called the Deutsche Burschenschaft (DB). In 1883, the General German Burschenbund (ADB), the umbrella organization of the so-called reform fraternities , emerged as a countermovement . In 1907 the fraternities of the Austrian Empire founded their own umbrella organization: the fraternity of the Ostmark (BdO).

In 1896 the descendants of German immigrants founded the Araucania fraternity in Santiago de Chile, the first of five fraternities in Chile today .

Student fraternities flourished in the German Empire. During this time, many fraternities also acquired their own corporation houses . In 1913, 45 of the 66 member unions of the DB had their own house, while the technical fraternities of the RVdB had 16 out of 35. In Austria, the situation was different, here in 1913 only six of the 41 fraternities united in the BdO had their own house.

Fraternities in the Weimar Republic (1919–1933)

The outcome of the First World War and the provisions of the Paris suburb contracts also sealed the downfall of the German-speaking universities in Strasbourg and Chernivtsi . Fraternities resident there had to stop their activities or relocate to other university towns.

Although the constitution of the Weimar Republic had taken over large parts of the fraternity-based Paulskirche constitution, many young fraternity members were monarchistic or were close to the Conservative Revolution , while most of the old men supported the new form of government.

The fraternities of the former Austrian Empire were incorporated into the DB in 1919, whereupon the BdO ceased to exist. The anti-Semitism then took to and within the DB and led in 1920 to the decision to take no more Jews as members. On the other hand, fraternities held many important positions in the new state. The most famous fraternity member was the Reich Chancellor and Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann , one of the pioneers of Franco-German friendship and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate .

In 1920, the Association of German Boys (VDB), another reform burschenschaftliche Korporationsverband was founded. In contrast to those of the DB and the ADB, the fraternities of the VDB rejected the scale length.

To Adolf Hitler seized power fraternity behaved not uniform. She was enthusiastically welcomed, as by large parts of the population, also by a large part of the fraternity, who sometimes held leading offices, while others were occasionally even active in the resistance (e.g. Hermann Kaiser ). Shortly afterwards, some associations excluded their Jewish members. In many of their publications, at the latest with the seizure of power, an anti-Semitic attitude becomes obvious.

The German fraternity as an umbrella organization had even before Hitler's seizure of power " Nazism as an essential part of the nationalist liberation movement " by a decision on the Burschentag 1932 " yes ," but in the same decision, the National Socialist German Students' League failed the trust (NSDStB). In the same year, under the leadership of DB, the " University Political Working Group of Student Associations " (Hopoag), which was in opposition to the NSDStB, was founded, but was dissolved by the new rulers in April 1933.

Coordination and dissolution in the Third Reich (1933–1945)

After the seizure of power of the Nazis was BdO in Austria launched again after the fraternities based outside of the German Reich had to leave the DB for political reasons.

From 1934 onwards, all student associations and unions were put under increasing pressure as part of the Gleichschaltung to integrate them into the NSDStB , which was to be established as the only major student organization. To this end, the umbrella organizations were forced to introduce the leader principle , and then numerous corporation associations were forcibly merged. In 1934 the ADB was integrated into the DB. The VDB was supposed to merge with the Schwarzburgbund , but this never happened. The so-called “Feickert Plan”, named after the leader of the also synchronized German Student Union (DSt) Andreas Feickert , also provided for the conversion of all student associations into “ comradeships ” of the NSDStB.

There was resistance to these and other changes imposed on the fraternity from outside: In the same year, numerous fraternities that had left the DB and were excluded founded the old fraternity , which, however, had to be dissolved again in 1935. Two days later, on October 18, 1935, the DB also disbanded. After Rudolf Hess finally forbade all student members of the NSDAP from membership in a student association in March 1936 , active public life became impossible. By the end of the year, most of the remaining fraternities dissolved. The rest turned into comradeships, some were able to continue their traditions in this way.

After the annexation of Austria in 1938, the occupation of the " remaining Czech Republic " in 1939, the incorporation of Luxembourg in 1940, and the occupation of the Netherlands and Belgium , the fraternities there and the BdO were also dissolved, so that from this point on only the four fraternities existed in Chile .

post war period

After the National Socialists had banned all open student associations and integrated their members into comradeships within the National Socialist German Student Union, the classic life of associations was only revived after 1945 in the western occupation zones, the later Federal Republic, and in Austria, but not on the soil of the GDR . Since the Soviet administration signaled that they would not tolerate any connection life on the territory of the Soviet zone of occupation, the connection structures located there tried to bring as much material and historical memorabilia as possible to the West and to establish a new existence at a university in the emerging Federal Republic. Berlin connections moved their headquarters to the newly founded Free University of Berlin or to the Technical University of Berlin in the western part of the city. The connections that had been re-established in the West kept in contact with the "old men" in the GDR only in a very discreet way for security reasons. The communist leadership of the GDR viewed the fraternities negatively as conservative-reactionary associations. In this way, the student union culture in the area of the GDR disappeared from the consciousness of the population. A substitute function later took over student associations of the GDR . It was only after the reunification (GDR) that fraternities were able to operate again in the new federal states.

As part of the NSDStB, the comradeships were banned by the Allied administrative authorities and their houses were confiscated.

The bans on German associations issued in 1945 by the Allied military governments also affected student associations. This ban was not officially lifted again in the Federal Republic until 1950. In that year, both the DB and the VDB were re-established, but not the ADB, whose fraternities largely participated in the re-establishment of the DB. The non-beating VDB dissolved again in 1956, most of its member associations went to the Deutsche Burschen-Ring (DBR) founded in 1957 , which existed until 1964. Today most of the former VDB fraternities are free of umbrella organizations or members of the Schwarzburgbund (SB). Today there is no longer a reform fraternity umbrella organization.

After the war, the Austrian fraternities founded their own umbrella organization with the General Delegate Convent , which in 1959 was renamed the German Burschenschaft in Austria (DBÖ) and from 1952 had a work and friendship agreement with the DB. The position that Austria was part of a German nation became the core ideology of the Austrian fraternities. This position was tried to spread through right-wing media such as Die Aula , and from 1970 also through campaigns and rallies. These activities met with little public awareness, which the fraternities explained with a low connection of the Austrian population to the GDR and to areas such as the Memelland. From 1990 onwards, the fraternities' activities to convey a national agenda concentrated on Austrian territorial claims.

Crisis of the German fraternity

Since the end of the 1950s, there have been increasing efforts in the DB, as in many other beating umbrella organizations , to abandon or at least exempt student fencing , which was only made mandatory again in 1954 . The social climate changed by the German student movement of the 1960s increased the desire among many young fraternity members to adapt the traditional student customs to the zeitgeist . The scale was often considered to be a traditional relic that many young students could no longer convey. But these then progressive ideas could not count on a majority at the Burschentag of the DB, all applications in this direction were rejected. Because of the abandonment of the scale length, numerous fraternities were excluded from the DB at the end of the 1960s or withdrew from the DB through self-exclusion because of the abandonment of association principles.

Since the re-establishment of the DB in 1950, there had also been efforts to bring fraternities together independently of state borders in a common umbrella organization, as had already been the case between 1919 and 1933. These efforts led to the application for the merger of the DB with the DBÖ at the Burschentag in Nuremberg in 1961. After the application had not found the necessary majority, proponents of the merger from the two associations founded the Burschenschaftliche Gemeinschaft (BG).

The sharp disputes over these two questions led DB into a deep crisis, which also made a split in the association appear possible. Applications to adjourn or dissolve DB testify to the inability of the association to act at this time. In 1970 a statute committee was set up, which was able to present a compromise solution on the following Burschentag, which included four major changes:

“The determination of the individual connections will in future be free. In return, the fraternities from Austria can join the DB until August 31, 1972. In addition, the people-related concept of fatherland is anchored in the principles and the so-called self-exclusion clause becomes effective if the principles are abandoned or violated. "

At the Burschentag in Landau in 1971, the fourth amendment of this historical compromise that was negotiated was finally approved with the required 3/4 majority. The long-feared break between conservative and liberal fraternities was thus avoided - at least for the time being. The compromise ended "one of the darkest chapters of DB in the post-war period", however, "only pro forma": "Although the unit could be saved through this so-called" historical compromise ", a conformity in thinking was not achieved."

Contrary to what was originally planned, the BG did not dissolve after the compromise. Many fraternities left the BG in 1971. By joining the Austrian fraternities, the influence of the BG on the DB was nevertheless strengthened.

Many DB fraternities have been providing or exempting their members from beating determination marks since 1971. The DB today therefore consists of both compulsory and optional fraternities.

From the mid-1970s onwards, membership growth in many fraternities increased again, even if the numbers from before the student movement were no longer matched.

The spin-off of the “ Neue Deutsche Burschenschaft ” (NeueDB) from the DB in 1996 is also due to the rejection of the people-based concept of the fatherland, which was raised to the federation principle in 1971 . Only fraternities based in the Federal Republic of Germany can become members of the NeueDB. For the NeueDB, "the so-called historical compromise in 1971, which abolished compulsory censorship and made it possible for German fraternities to be accepted into Austria [...] only superficially solved the problems."

In 2007 and 2008, the three Jena fraternities, known as the original fraternities, left the DB. This is often seen as the preliminary climax of a process of disintegration in this association, which reform efforts, such as the Stuttgart Initiative, were unable to change.

On October 2, 2016, 27 fraternities, the majority of which were former members of DB, founded the general German fraternity corporation .

The different types of fraternities

Most of the student fraternities that call themselves “fraternity” refer to the legacy of the original fraternity. However, there are sometimes huge differences between the individual fraternity types. One of the most important differences is the position in relation to the scale length . The type of the beating fraternities is the larger and older. Most of these fraternities are today either mandatory or optional. Unsuccessful fraternities emerged mainly after 1848 with the Christian fraternities and around 1900 with the reform fraternities . But there are also some former fraternities that - especially in the 1960s - completely gave up the scale.

Striking fraternities

Although the original fraternities themselves hadn't been successful, the early fraternities often took over from the corps as early as the 1820s . At the same time there was the first split within the fraternity: the Arminian and Germanic fraternities emerged.

Arminian and Germanic fraternities

Since 1825 the fraternity movement divided more and more into a radical republican and national line ("Germania") and a university-political and free-thinking- liberal line ("Arminia"). This division first arose in Erlangen and eventually spread to the entire fraternity movement. While the Germanic peoples were the “armed advocates of a tight union life ” who “wanted to make theoretical preoccupation with political problems obligatory”, the Armines aimed “at internalizing fraternity life and rejected political discussions.” 1829 came it finally broke: the Arminian fraternities were excluded from the general German fraternity by the Germanic majority.

Red and white fraternities

At the beginning of the 20th century, a further diversification manifested itself within the German fraternity, which from then on largely superimposed the first division into Arminia and Germania : the “red” and the “white direction” emerged.

The red fraternities describe themselves as down-to-earth and place political education in the foreground, while the white fraternities place greater value on social manners and "emphatically emphasize the corporate character and the tasks of the individual fraternities in terms of weapons students and the preservation of the traditional forms of a tightly knit community life" emphasize.

This division was formative for the association policy of the DB until the foundation of the Burschenschaftliche Gemeinschaft (BG). After both the BG and the New German Burschenschaft were founded jointly by red and white fraternities in 1961 , this feature also took a back seat in many fraternities.

Reform fraternities

The reform fraternities that emerged since the end of the 19th century referred more than the “classic” fraternities to the liberal-democratic legacy of the original fraternity. They criticized many of the traditions of other fraternities as outdated or unsurprisingly ( see also: General German Burschenbund ). After 1950, most of the successful reform fraternities joined the DB.

Technical fraternities

Fraternities at technical colleges and universities of applied sciences were excluded from membership in “academic” umbrella organizations such as DB for a long time. Those Bünder who did not join the DB - like the Rüdesheimer Verband deutscher Burschenschaften (technical universities) in 1919 or the Deutsche Hochschul-Burschenschaft (technical colleges) in 1999 - developed their own traditions and peculiarities. These “engineering associations” are today in Austria in the Conservative Delegate Convent and in Germany with other technical associations in the Federation of German Engineering Corporations .

Unbeatable fraternities

Soon after the fraternities took over the scale, student associations were founded that rejected the scale. The first was the Christian student association Uttenruthia Erlangen , founded in 1836 ( see also: Christian student associations ). The oldest non-beating fraternity is the Germania Göttingen. Christian fraternities first came into being in the second half of the 19th century. Today they are mostly organized in the umbrella organizations Schwarzburgbund and Ring Katholischer Deutscher Burschenschaften .

At the beginning of the 20th century reform fraternities emerged, which also rejected the use of scales. They have been organized in the Association of German Boys since the 1920s, and after the Second World War they largely joined the Schwarzburgbund.

Pennale fraternities

Mainly in Austria, but also increasingly in Germany, there are pennale fraternities , i.e. student associations that are also fraternities.

Associations

Most of the fraternities today are organized in the corporation associations Deutsche Burschenschaft (DB), Neue Deutsche Burschenschaft (NeueDB) and Allgemeine Deutsche Burschenschaft (ADB). Many fraternities in Austria belong - partly in addition to membership in the DB - to the German Burschenschaft in Austria (DBÖ) or to the Conservative Delegate Convent (CDC). In addition, there are various other umbrella organizations, especially in Germany, which are composed entirely or partially of fraternities.

German fraternity

The German Burschenschaft sees itself in the patriotic tradition of the original fraternity and unites connections from the Federal Republic of Germany and the Republic of Austria .

Since the Historical Compromise of 1971, the German Burschenschaft has released its member federations from compulsory censorship and since then has been accepting fraternities from Austria again in return. The people- related concept of fatherland , which includes the German language and cultural area and thus the “German cultural nation” or “German nationality”, continues to apply .

Austrian umbrella organizations

In Austria, there is the German Burschenschaft in Austria (DBÖ), the majority of which are also members of the DB, and the Conservative Delegate Convent (CDC). Both associations are mandatory and have friendship and work agreements with DB.

Fraternity

The Burschenschaftliche Gemeinschaft (BG) now has 36 fraternities from the DB, DBÖ and CDC. This makes it the second largest fraternity interest group below the association level, after the fraternity future initiative . The original aim of the BG was to enable fraternities from Austria to join the DB. The BG was founded in 1961 in the house of the Munich fraternity Cimbria after an application for a merger of the DB with the DBÖ at the Burschentag had not found the necessary majority of the German fraternities. This goal was finally achieved in 1971 through the historic compromise .

The BG can exert influence over the entire organization through the three main leading bodies of DB. Since two-thirds majorities are required for new admissions, for example , it has a kind of veto function and thus has a great influence. The BG advocates reintroducing the principle of compulsory censorship in the DB. Since it is also committed to history, many critical political discussions refer to past events, such as the expulsions from the former eastern territories of the former German Reich and the recognition of territorial assignments. In this context, however, a blocking minority among the DB fraternities has so far refused to tighten the scaling obligations.

Other associations

Fraternities that belong to other associations or are free of associations often represent more liberal political programs or are entirely non-political. All are colored , but the weapons student principle ranges from non-striking to mandatory.

- The New German Burschenschaft (NDB) split off from the German Burschenschaft in 1996 after internal differences of opinion in order to deliberately differentiate itself from it and expressly reject any revanchism. In contrast to DB, it is committed to the civic concept of fatherland and currently consists of 10 leagues.

- The Allgemeine Deutsche Burschenschaft (ADB) was founded in 2016 and consists mainly of former members of the German Burschenschaft; it consists of 27 frets.

- The Süddeutsche Kartell (SK), an amalgamation of six obligatory former DB fraternities, sees itself as a federation at several university locations.

- The Schwarzburgbund (SB) consists of non-striking, Christian associations, including predominantly those who call themselves fraternity. Some of the SB fraternities are mixed connections .

- The Ring Katholischer Deutscher Burschenschaften (RKDB) in Germany and the Ring Katholisch Akademischer Burschenschaften (RKAB) in Austria comprise a total of 21 non-striking Catholic fraternities.

- The Federation of German Engineering Corporations (BDIC) consists of student associations who are active at technical universities, including 18 fraternities of different characterization.

- In Chile , the Federation of Chilean Fraternities (BCB) is the umbrella organization of the five Chilean fraternities and has a friendship and work agreement with DB.

In addition, there are many fraternities not belonging to any association, most of which have left an umbrella organization. They are often ideologically independent and, due to their diversity, difficult to compare with the member federations of the large fraternity umbrella organizations. Some fraternities that are not part of the association now also accept women or non-academics.

criticism

A frequent accusation is that fraternities have an elitist understanding of society. In various publications, at events and demonstrations, the traditions of the fraternities and other connections are often put into a right-wing extremist context by their opponents . In particular, the fraternities of the fraternity are often politically placed on the right fringes of the student associations.

Germany

Günther Beckstein , himself an old man of an artistic student association , criticized right-wing extremists as Bavarian Minister of the Interior in 2001 who tried to gain influence in academic fraternities and through them at universities. Bavaria therefore does not look the other way when right-wing extremists maintain contact with fraternities or even try to undermine academic connections.

On the occasion of a lecture by Egon Bahr at a Berlin fraternity, the Jusos criticized in an open letter in 2005:

“Fraternities treat people unequally, women are often structurally disadvantaged because of their gender. For many fraternities, racial criteria, nationality, sexual orientation, religion or conscientious objection are exclusion criteria for admission. (...) We consider it unacceptable if social democrats, by speaking to fraternities, help to ensure that fraternities gain influence and that their elitist and undemocratic worldview becomes socially acceptable. "

In 2006, the SPD then decided that membership in a fraternity of fraternity lichen community is not a member of the SPD compatible was. The SPD has finally lost its first lawsuit for the exclusion of a fraternity.

Austria

Fraternities in Austria are generally attested by critics as having a strong connection to the German national camp, which is expressed, among other things, in the principle of the “people- related fatherland concept”, which defines the “German fatherland independent of state borders” and includes Austria. The idea of an independent Austrian nation is rejected with varying degrees of clarity.

Individual Austrian fraternities were mentioned in the annual management report of right-wing extremism by the Austrian Ministry of the Interior in the 1990s . The Viennese right-wing extremism researcher Heribert Schiedel speaks of the central importance of the fraternities "at the interface between right-wing extremism , legal German nationalism and (neo) Nazism " .

Well-known fraternity members

Physicians and natural scientists

- Dietrich Barfurth (1849-1927), anatomist; Burschenschaft Brunsviga Göttingen, Burschenschaft Alemannia Bonn and Burschenschaft Obotritia Rostock

- Hans Berger (1873–1941), psychiatrist, developed the electroencephalogram (EEG); Arminia fraternity in the Jena castle cellar

- Carl Bosch (1874–1940), chemist and industrialist; Berlin fraternity Cimbria

- Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt (1885–1964), German neurologist and co-discoverer of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- Irmfried Eberl (1910–1948), Nazi euthanasia doctor and 1st commandant of the Treblinka extermination camp; Fraternity Germania Innsbruck

- Wilhelm Exner (1840–1931), forest scientist; Vienna Academic Fraternity Olympia

- Hans Fischer (1881–1945), chemist, Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1930; Fraternities Alemannia Marburg and Alemannia Stuttgart

- Hans Geiger (1882–1945), physicist, inventor of the Geiger counter; Fraternity of the Bubenreuther Erlangen

- Carl Graebe (1841–1927), chemist, determined the chemical structure of the dye alizarin

- Bernhard von Gudden (1824–1886), professor of psychiatry and psychiatric expert on King Ludwig II of Bavaria; Bonn fraternity Frankonia

- Heinrich Hertz (1857-1894), physicist; Fraternity Cheruskia Dresden

- Helmut Himpel (1907–1943), resistance fighter in the Third Reich; Karlsruhe Burschenschaft Germania (today Teutonia )

- Ludolf von Krehl (1861–1937), physician; Fraternity Frankonia Heidelberg

- Widukind Lenz (1919–1995), human geneticist; Germania Tübingen fraternity

- Justus von Liebig (1803–1873), chemist, founder of organic chemistry; Original fraternity from Bonn and Erlangen

- Otto Loewi (1873–1961), physician; Germania Strasbourg fraternity

- Carl Mühlenpfordt (1878–1944), architect; Braunschweig fraternity Alemannia

- Felix Oberländer (1851–1915), professor at the TU Dresden, founder of modern urology; Leipzig fraternity Dresdensia

- Arnold Sommerfeld (1868–1951), nuclear physicist; Fraternity Germania Koenigsberg

Engineers, entrepreneurs and industrialists

- Adolf Daimler (1871–1913), son of Gottlieb Daimler , director and co-owner of Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft ; Fraternity Hilaritas Stuttgart

- August Föppl (1854–1924), engineer; Old Darmstadt fraternity Germania

- Gerhard Heimerl (1933), engineer, transport scientist and inventor from Stuttgart 21 ; Munich fraternity Franco-Bavaria , fraternity Hilaritas Stuttgart

- Ernst Heinrich Heinkel (1888–1958), aircraft manufacturer; Stuttgart fraternity Ghibellinia

- Hanns Jencke (1843–1910), chairman of the board of directors of the Krupp company and chairman of the Central Association of German Industrialists; Leipzig fraternity Dresdensia

- Alfred Kärcher (1901–1959), mechanical engineer; Alemannia Stuttgart fraternity

- Georg Knorr (1859–1911), engineer and entrepreneur, inventor of the Knorr-Bremse ; Braunschweig fraternity Thuringia

- Hartmut Mehdorn (* 1942), industrial manager and mechanical engineer, former CEO of Deutsche Bahn ; Fraternity Frankonia Berlin

- Waldemar Petersen (1880–1946), inventor of the Petersen coil ; Fraternity of Germania Darmstadt

- Ferdinand Porsche (1875–1951), automobile manufacturer; Vienna Academic Fraternity Bruna Sudetia (honorary member)

- Franz Reuleaux (1829–1905), engineer, founder of kinematics ; Karlsruhe Burschenschaft Teutonia

- Albrecht Schumann (1911–1999), engineer, CEO of Hochtief ; Karlsruhe Burschenschaft Teutonia

- Walther Wunsch (1900–1982), engineer, board member of Ruhrgas AG ; Karlsruhe Burschenschaft Germania (today Teutonia )

Humanities scholars and lawyers

- Julius von Ficker Ritter von Feldhaus (1826–1902), legal historian; Bonn fraternity Frankonia

- Reinhard von Frank (1860–1934), eminent criminal lawyer ( Frank formula), fraternity Germania Marburg and fraternity Derendingia Tübingen

- Hermann Höpker-Aschoff (1883–1954) ( FDP ), first President of the Federal Constitutional Court; Arminia fraternity in the Jena castle cellar

- Theodor von Kobbe (1798–1845), lawyer, human rights activist and writer; Jena original fraternity

- Friedrich Meinecke (1862–1954), historian; Burschenschaft Saravia Berlin

- Theodor Mommsen (1817–1903), historian; Fraternity Albertina Kiel

- Wilhelm Oncken (1838–1905), historian; Fraternity of Frankonia in Heidelberg

- Franz Oppenheimer (1864–1943), economist and sociologist; Fraternities Alemannia Freiburg and Hevellia Berlin

- Karl Sack (1896–1945), judge at the Reich Court Martial, resistance to National Socialism in the Third Reich; Fraternity Vineta Heidelberg

- Eduard von Simson (1810–1899), President of the Frankfurt National Assembly 1848–49, President of the Imperial Court, Fraternity of the Königsberg fraternity

- Friedrich Julius Stahl (1802–1861), legal philosopher and politician

- Lorenz von Stein (1815–1890), constitutional lawyer and sociologist

- Karl Steinbauer (1906–1988), Evangelical Lutheran theologian and member of the Confessing Church ; Germania Erlangen fraternity

- Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936), founder of sociology in Germany; Arminia fraternity in the Jena castle cellar

- Heinrich von Treitschke (1834–1896), historian and publicist; Bonn fraternity Frankonia

- August Vilmar (1800–1868), conservative Lutheran theologian , Old Marburg Burschenschaft Germania

- Max Weber (1864–1920), sociologist, economist and economic historian; Fraternity Allemannia Heidelberg

Poets, writers, musicians and journalists

- Kai Diekmann (* 1964), journalist, editor-in-chief of Bild ; Münster fraternity Franconia

- August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben (1798–1874), Germanist and poet; Old Göttingen fraternity

- Walter Flex (1887–1917), poet of the youth movement, killed in the First World War; Fraternity of the Bubenreuther Erlangen

- Julius Mosen (1803–1867), poet and writer; Original Jena fraternity

- Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), philosopher; Bonn fraternity Frankonia (resigned)

- Fritz Reuter (1810–1874), Low German writer; Original fraternity of Jena, fraternity Germania Jena

- Joseph Victor von Scheffel (1826–1886), writer; Fraternity of Frankonia in Heidelberg

- Robert Schumann (1810–1856), composer and pianist of the Romantic period; Fraternity Markomannia Leipzig, Corps Saxo-Borussia Heidelberg

- Theodor Storm (1817–1888), lawyer and writer; Fraternity Albertina Kiel

- Ludwig Uhland (1787–1862), poet and literary scholar; Germania Tübingen fraternity

Officers

- Hermann Kaiser (1885-1945), teacher , staff officer, wg. Executed involved in the Hitler assassination attempt ; Fraternity of the Pflüger Halle zu Münster

- Günter Kießling (1925–2009), General, Commander of the NATO Land Forces; Fraternities Sugambria Bonn and Germania Bonn

- Karl Mauss (1898–1959), General of the Armored Force , bearer of the Knight's Cross with oak leaves, swords and diamonds ; Hamburg fraternity Germania

- Otto Skorzeny (1908–1975), SS-Obersturmbannführer, head of several commando companies ; Fraternity Markomannia Vienna

Politician

- Franz Adickes (1846–1915), Lord Mayor of Frankfurt / Main. Fraternity Alemannia Heidelberg

- Victor Adler (1852–1918), politician, founder of the Social Democratic Workers' Party in Austria; Fraternity Arminia Vienna

- Robert Blum (1807–1848), politician, member of the Frankfurt National Assembly; Leipzig Burschenschaft Germania (honorary member)

- Rudolf Breitscheid (1874–1944), social democratic politician; Arminia Marburg fraternity

- Eberhard Diepgen (* 1941) (CDU), former Governing Mayor of Berlin ; Burschenschaft Saravia Berlin

- Hermann Dietrich (1879–1954), politician of the German Democratic Party and minister in the Weimar Republic; Arminia Strasbourg fraternity

- Friedhelm Farthmann (* 1930), ( SPD ), former Minister of State for Labor and Social Affairs in North Rhine-Westphalia , parliamentary group chairman; Königsberg fraternity Gothia zu Göttingen

- Heinrich Freiherr von Gagern (1799–1880), first President of the Frankfurt National Assembly ; Original Jena fraternity

- Ferdinand Goetz (1826–1915), doctor, politician, chairman of the board of the German Gymnastics Association; Leipzig fraternity Germania

- Johannes Gudenus (* 1976) ( FPÖ ) party member until 2019, non-executive city council deputy mayor of Vienna (2015–2017), member of the national council and executive club chairman of the FPÖ (2017–2019); pennale fraternity Vandalia Vienna

- Dieter Haack (SPD), former Federal Minister of Construction; Burschenschaft of the Bubenreuther in Erlangen

- Christian Hafenecker (1980) ( FPÖ ), FPÖ General Secretary, Member of the National Council; Fraternity Nibelungia in Vienna

- Jörg Haider (1950–2008) (FPÖ, BZÖ ), Governor of Carinthia ; Burschenschaft Silvania Vienna (later hunters)

- Ernst von Harnack (1888–1945), social democratic politician, executed as a resistance member in 1945, fraternity Germania Marburg

- Theodor Herzl (1860–1904), founder of political Zionism; Burschenschaft Albia Wien (resigned and later member of the Jewish association Kadimah)

- Hermann Höcherl (1912–1989) ( CSU ), Federal Minister of the Interior; Fraternity Babenbergia Munich

- Norbert Hofer (* 1971) ( FPÖ ), deputy party chairman (until 2019) and party chairman-designate (2019), candidate for federal presidency 2016 , federal minister (2017-2019); Pennal-conservative fraternity Marko-Germania zu Pinkafeld

- Karl Jarres (1874–1951) ( DVP ), Lord Mayor of Duisburg , candidate for the presidential election in 1925 ; Alemannia Bonn fraternity

- Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903–1946) (NSDAP), head of the Reich Security Main Office ; Fraternity Arminia Graz

- Reiner Klimke (1936–1999), dressage rider, multiple Olympic champion, politician (CDU); Fraternity of the Pflüger Halle zu Münster

- Ferdinand Lassalle (1825–1864), publicist and workers' leader, one of the founding fathers of the SPD ; Old Raczek fraternity in Breslau

- Wilhelm Adolph Lette (1799–1868), German social politician, founder of the Lette Association Berlin; Teutonia Heidelberg 1816 and co-founder of the Berlin fraternity Arminia 1818

- Franz Mehring (1846–1919) (SPD, KPD), politician, Marxist historian; Leipzig fraternity Dresdensia

- Otto Meissner (1880–1953), head of the office of the Reich President from 1919 to 1945; Old Strasbourg fraternity Germania

- Johann Georg Mönckeberg (politician, 1839) , First Mayor of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg 1890–1908; Fraternity Frankonia Heidelberg

- Hans Mühlenfeld (1901–1969), Ambassador to the Netherlands and Australia, 1963 to 1965 Minister of Education of Lower Saxony; Fraternity of Hannovera Göttingen

- Carl L. Nippert (1852-1904), lieutenant governor of the State of Ohio ; Karlsruhe Burschenschaft Teutonia

- Raphael Pacher (1857–1936), Governor of German Bohemia, State Secretary for Education in German-Austria; Fraternity Teutonia Prague

- Eugen Philippovich von Philippsberg (1858–1917), national economist, Arminia Graz

- Peter Ramsauer (* 1954) ( CSU ), Federal Minister for Transport, Building and Urban Development ; Munich fraternity Franco-Bavaria

- Georg Heinrich Ritter von Schönerer (1842–1921), German national and anti-Semitic politician in Austria; Vienna academic fraternity of Teutonia

- Carl Schurz (1829–1906), participant in the revolution of 1848; Major General in the American Civil War, US Secretary of the Interior; Bonn fraternity Frankonia

- Markus Söder (* 1967) ( CSU ), Prime Minister ; Fraternity Teutonia Nuremberg

- Theodor Sonnemann (1900–1987), State Secretary, President of the Cooperative and Raiffeisen Association; Fraternity Holzminda Göttingen

- Heinz-Christian Strache (* 1969) ( FPÖ ), Federal Party Chairman of the FPÖ (2005–2019) and Vice Chancellor of Austria (2017–2019); pennale fraternity Vandalia Vienna

- Gustav Stresemann (1878–1929), Reich Chancellor and Foreign Minister, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate ; Fraternities Neogermania Berlin and Suevia Leipzig

- Bernhard Vogel (* 1932) (CDU), Prime Minister of Rhineland-Palatinate and Thuringia; Fraternity Arminia Mainz (honorary member)

- Emil Welti (1825–1899), Swiss President six times; Arminia fraternity in the Jena castle cellar

See also

literature

General

- Hans-Georg Balder: The German fraternities. Hilden 2005. ISBN 3-933892-97-X .

- Hans-Georg Balder: History of the German fraternity. Hilden 2006. ISBN 3-933892-25-2 .

- Hans-Georg Balder, Rüdiger B. Richter: Corporates in the American Civil War , Hilden 2008. ISBN 978-3-933892-27-0 .

- Hans-Georg Balder: The German fraternity in its time. Hilden 2009. ISBN 978-3-940891-20-4 .

- Frank Grobe: Compass and gear. Engineers in the bourgeois emancipation struggle around 1900. The history of the technical fraternity, in: Oldenhage, Klaus (ed.), Representations and sources for the history of the German unity movement in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, vol. 17, Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2009. ISBN 978- 3-8253-5644-6 .

- Frank Grobe: With fraternity greetings. Color cards of the Rüdesheimer Verband deutscher Burschenschaften , Essen 2011. ISBN 978-3-939413-16-5 .

- Horst Grimm, Leo Besser-Walzel: The corporations. Umschau Verlag Breidenstein, Frankfurt am Main 1986. ISBN 3-524-69059-9 .

- Peter Krause : O old lad glory - the students and their customs. Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1997. ISBN 3-222-12478-7 .

- Alfred Thullen: The castle cellar in Jena and the fraternity on the castle cellar from 1933–1945. Heidenheim adB 2002. ISBN 3-933892-49-X .

- Matthias Stickler : The crisis of the German fraternity . Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of February 14, 2014. Online version .

History of the German fraternity

- Paul Wentzcke : History of the German fraternity. Vol. 1. Early and early times up to the Karlovy Vary resolutions . Heidelberg 1965. ISBN 3-8253-1338-7 .

- Georg Heer : History of the German Burschenschaft , Vol. 2. The demagogue time. From the Carlsbad resolutions to the Frankfurt Wachensturm (1820–1833) . Heidelberg 1965. ISBN 3-8253-1342-5 .

- Georg Heer: History of the German fraternity. Vol. 3. The time of progress. From 1833 to 1859 . Heidelberg 1965. ISBN 3-8253-1343-3 .

- Georg Heer: History of the German fraternity. Vol. 4. The fraternity during the preparation of the Second Reich, in the Second Reich and in the World War. From 1859 to 1919 . Heidelberg 1977. ISBN 3-533-01348-0 .

- Gerhard Neuenhoff: Evidence for the development of the Arministic and Germanistic fraternity direction. SC and fraternity in Jena 1830 to 1832 . Einst und Jetzt , Vol. 32 (1987), pp. 99-108.

- Helma Brunck: The German Burschenschaft in the Weimar Republic and in National Socialism. Munich 2000. ISBN 3-8004-1380-9 .

- Harald Lönnecker: "To have always served Germany is our highest praise!" Two hundred years of German fraternities. A commemorative publication for the 200th anniversary of the founding day of the fraternity on June 12, 1815 in Jena . Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2015, ISBN 978-3-8253-6471-7 .

Critical

- Diana Auth, Alexandra Kurth: Male union gentleness. Research situation and historical review , in: Christoph Butterwegge , Gudrun Hentges (Ed.): Old and New Rights at the Universities. Agenda, Münster 1999. ISBN 3-89688-060-8 .

- Ludwig Elm , Dietrich Heither , Gerhard Schäfer (eds.): Füxe boys, old men, men - student corporations from the Wartburg Festival to today. Papyrossa, Cologne 1993. ISBN 3-89438-050-0 .

- Dietrich Heither , Gerhard Schäfer : Student connections between conservatism and right-wing extremism. in: Jens Mecklenburg (Ed.): Handbook of German Right-Wing Extremism. Berlin 1996. ISBN 3-88520-585-8 .

- Dietrich Heither: Allied men. Papyrossa, Cologne 2000. ISBN 3-89438-208-2 .

- Dietrich Heither, Michael Gehler , Alexandra Kurth: Blood and Paukboden. Fischer, Frankfurt 2001. ISBN 3-596-13378-5 .

- Oskar Scheuer : Burschenschaft and the Jewish question. Hilden 2003. ISBN 3-933892-47-3 . Original: fraternity and Jewish question. Racial anti-Semitism in the German student body. Berlin 1927

Web links

Associations and working groups:

- General German fraternity

- German fraternity

- New German fraternity

- Conservative delegate convention of the student fraternities of Austria

- Fraternity

General:

- The fraternities (private information portal)

- Mastermind fraternities, the power of student associations, zdf-info, 04.10.18

Publications:

- Society for fraternity historical research e. V. (archive and library of the German fraternity)

Critical:

- Helene Bubrowski ( taz ): pillars of the future society , October 12, 2002.

- Burschi-Reader of the anti-fascist press archive and education center : fraternities and student associations (on structure, content, history and background) (PDF; 419 kB)

- Alexandra Kurth: The image of men among the fraternity members , right-wing extremism dossier of the Federal Agency for Civic Education , November 28, 2014

- Alexandra Kurth / Bernd Weidinger: Fraternities: history, politics and ideology , right-wing extremism dossier from the Federal Agency for Civic Education, September 26, 2017

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Isis or Encyclopädische Zeitung for the Wartburg Festival 1817 (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- ↑ fraternity / fraternity in online Duden , accessed in May of 2019.

- ↑ Alfons Fridolin Müller: The pejoration of personal designations by suffixes in New High German. Burch, Altdorf 1953. p. 172.

- ^ Edwin A. Biedermann: Lodges, clubs and brotherhoods. Droste, 2007. p. 253.

- ↑ Hans-Gerd Jaschke: Political Extremism . 1st edition. Vs Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-531-14747-1 (Chapter 3 - Lines of Development).

- ^ Rainer Pöppinghege: Between radicalism and adaptation. 200 years of student history , in: Jan Carstensen, Gefion Apel (ed.): Quick-witted! Student associations in the empire. Reader and exhibition catalog on behalf of the Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe for the exhibition in the Westphalian Open-Air Museum Detmold from August 15 to October 31, 2006, p. 12f. ISBN 3-926160-39-X ISSN 1862-6939

- ↑ Herman Haupt (ed.): Sources and representations on the history of the fraternity and the German unity movement , Volume 1, C. Winter, 1910. P. 124.

- ↑ Karl Klüpfel: The German striving for unity in their historical context . Gustav Mayer, Leipzig 1853. p. 401.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History. Since 1789. Part 1: Reform and Restoration. 1789 to 1830 , 2nd edition, Stuttgart et al. 1990, p. 722.

- ↑ cf. Klaus Wessel : The Wartburg Festival of the German Burschenschaft on October 18, 1817. Röth, Eisenach 1954 (publications of the Wartburg Foundation 2).

- ↑ Jost Hermand: A youth in Germany. Heinrich Heine and the Burschenschaft (PDF; 86 kB) , Berlin 2002. P. 6.

- ↑ die-corps.de: Heinrich Heine ( Memento of 10 January 2013, Internet Archive )

- ↑ Walter Schmidt : Life fates. Persecuted Silesian fraternities from the early 19th century. In: Würzburger medical history reports 22, 2003, pp. 449-521.

- ↑ Herman Haupt: Handbook for the German Burschenschafter , Frankfurt a. Main 1929, p. 16 and 42.

- ^ Burschenschaft , in: Großer Brockhaus, Encyclopedia in 20 volumes , 20th edition 1996.

- ↑ Harald Lönnecker : Der Frankfurter Wachensturm 1833. 175 years of uprising for national unity and freedom ( Memento from March 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Christa Berg: Handbuch der deutschen Bildungsgeschichte , Volume 3, CH Beck, 1987. ISBN 3-406-32385-5 . P. 244.

- ^ Peter Kaupp: Fraternity members in the Paulskirche.

- ↑ Frank Grobe: Compass and gear. Engineers in the bourgeois emancipation struggle around 1900. The history of the technical fraternity. (Representations and sources on the history of the German unity movement in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Volume 17. Ed. By Klaus Oldenhage). Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2009. S. 609.

- ^ Hans-Georg Balder: Frankonia-Bonn 1845-1995. The story of a German fraternity. WJK-Verlag, Hilden 2006, ISBN 3-933892-26-0 , p. 599.

- ^ The fraternity in the Third Reich and during the Second World War ( Memento from December 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Bernhard Weidinger: “In the national defensive struggle of the borderland Germans.” Academic fraternities and politics in Austria after 1945. Böhlau, 2014. pp. 53–54.

- ^ Bernhard Weidinger: "In the defensive struggle of the borderland Germans". Academic fraternities and politics in Austria after 1945. pp. 360–361.

- ^ Bernhard Weidinger: "In the defensive struggle of the borderland Germans". Academic fraternities and politics in Austria after 1945. p. 362.

- ↑ Helmut Blazek: Men's Associations. A story of fascination and power. Ch. Links Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-86153-177-1 . P. 152.

- ↑ Sonja Kuhn: The German Burschenschaft - a grouping in the field of tension between traditional formalism and traditional foundations - an analysis for the period 1950 to 1999. Diploma thesis in the degree program in education, philosophy, psychology at the University of Bamberg. Edited by the old gentlemen's association of the fraternity Hilaritas Stuttgart. Stuttgart 2002. ISBN 3-00-009710-4 . P. 127.

- ↑ Sonja Kuhn: The German Burschenschaft - a grouping in the field of tension between traditional formalism and traditional foundation - an analysis for the period 1950 to 1999. Diploma thesis, University of Bamberg, Stuttgart 2002, p. 128.

- ↑ Sonja Kuhn: The German Burschenschaft - a grouping in the field of tension between traditional formalism and traditional foundation - an analysis for the period 1950 to 1999. Diploma thesis, University of Bamberg, Stuttgart 2002, p. 129.

- ↑ Der Spiegel: Good in business . Issue 26/1976 of June 21, 1976, p. 50.

- ↑ Michael Hacker on the NeueDB website (accessed on March 21, 2008).

- ↑ Young Freedom : Hardened Fronts in Eisenach (May 28, 2010) and The Split was postponed (June 4, 2010).

- ↑ New Burschenschaftsverband: A little less right ( memento from October 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), mdr.de, accessed on October 11, 2016.

- ^ The fraternities as pioneers of the revolution of 1848 ( Memento of July 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Handbook for the German Burschenschafter , Frankfurt 1925, p. 118.

- ↑ Frank Grobe: Compass and gear. Engineers in the bourgeois emancipation struggle around 1900. The history of the technical fraternity. (Representations and sources on the history of the German unity movement in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Volume 17. Ed. By Klaus Oldenhage). University Press Winter, Heidelberg 2009.

- ↑ Homepage. General German Burschenschaft, accessed December 25, 2018 .

- ↑ Berliner Zeitung: Beckstein warns of Nazis at universities (June 15, 2001). Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Unispiegel: Influence of old gentlemen up to the party executive (January 17, 2006).

- ↑ Academic Freedom: Exclusion from Party

- ↑ Wolfgang Gessenharter , Thomas Pfeiffer (ed.): The new right: a threat to democracy? . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2004. ISBN 3-8100-4162-9 , p. 129.

- ↑ [1] DÖW - Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance May of 2002.

- ↑ Interview with H. Schiedel, published in: Gedenkdienst 3/2003.

- ↑ a b c See the main article of the Ibiza affair in 2019 as a background .

- ^ Helge Dvorak: Biographical Lexicon of the German Burschenschaft . On behalf of the Society for Burschenschaftliche Geschichtsforschung eV Ed .: Prof. Dr. Christian Hünemörder. Volume I: Politicians, Part 3: IL. Universitätsverlag C. Winter, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-8253-0865-0 , p. 278 ff .