Austrian identity

Austrian identity describes the “ we-feeling ” that people with Austrian citizenship or of Austrian origin ( old Austrians , Austrians abroad ) have developed to a greater extent since 1945 and which subjectively differentiates them from members of other countries . In this sense, the term Austrian identity is a collective cultural, social, historical, linguistic and ethnic identity that has developed in relation to the Austrian population, which has led to a feeling of togetherness within them and which results in a clear national awareness. This identity is constantly evolving and is differently pronounced among the population, especially with regard to the individual federal states, also with regard to the specific national awareness.

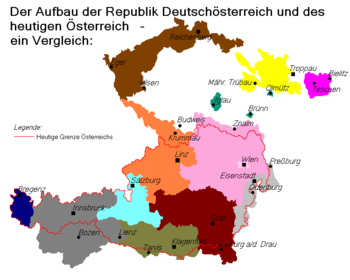

In the discourse about an Austrian identity and nation , many different, sometimes contradicting, concepts have been developed in terms of intellectual history. They range from the concept of Austrians eastern group of the Bavarian tribe and Austrians as part of a German nation to the Austrians as an independent primordial - ethnic nation. Today the notion of a separate and independent Austrian nation is predominant, with its borders varying depending on the ideological concept of the nation.

The modern Austrian identity developed in the 20th century is also associated with a special awareness of Austria in earlier centuries. The term Austria or the Austrians themselves, with the exception of the core countries at the time (cf. the federal states of Upper Austria , Lower Austria and Vienna as the area of the former Archduchy ), for centuries was more a synonym for the House of Austria and the respective domain of the princely dynasty , but not the name for a people. Likewise, according to the old interpretation, from the late Middle Ages to 1848 the respective estates ( nobility and knights , in Tyrol also the peasants) were the bearers of a specific national consciousness.

Already in the decades after 1870/71, and in particular immediately before the First World War as well as during and after the war found in both the Catholic and the liberal camp with Hugo von Hofmannsthal , Hermann Bahr , Robert Musil , Friedrich Heer or Torberg against the liberal German national A process of increasing Austrianization and more conscious demarcation from a German identity is taking place. The dividing line between Austrians and Prussians, the model of what William M. Johnston called the “Theresian people”, who lived in Central Europe, and the development of an “Austrian idea” were emphasized. The “Austrian idea” was the mediator role to be performed between the Latin, Germanic and Slavic civilization within the positive plurality of the Habsburg monarchy.

Especially after 1945, the Austrian identity was developed above all in contrast to the specifically Austrian German nationalism . A direct line from the dynastic Austrian consciousness to the Austrian consciousness of that time was not accepted due to the upheavals of the interwar period and the Second World War. Only after joining the European Union in 1995 and the incorporation of the Republic of Austria into a community of states is the “Austrian” increasingly perceived as a long-lasting historical cultural strand since the multinational monarchy. Because even the old Austria (the Danube Monarchy ) was seen by some as a “Europe in miniature” and even in the then multi-ethnic state attempts were made to overarch plural national and denominational identities with early forms of a supranational identity.

Differentiation approaches

Political discourses have been and continue to be held on the subject of the Austrian nation. The concept of identity is generally emotionally and ideologically charged; Ruth Wodak wrote:

“In this context, however, we cannot use the term identity unquestioningly. Because on the one hand the term is vague, on the other hand it is so highly complex and multilayered that an interdisciplinary approach has become indispensable for a scientific analysis that wants to do justice to the many components of Austrian identity. "

In many cases, for example, the views of some representatives of Austrian historiography, which had long been German-national oriented, such as Ernst Hoor, were criticized as "anti-Austrian historical falsification". The historian Taras Borodajkewycz , who was later forced to retire due to his attitude to National Socialism, called the Austrian nation a “bloodless literary homunculus” and a “mixture of presumptuousness and ignorance” with reference to Hoors statements. He also wrote: "The 'Austrian nation' only seems to thrive among weeds".

Since emotional and ideological tendencies play an essential role in the identification of the individual with the whole that is superordinate to him (from the point of view of those who affirm the concept of the nation), the nation, the concept of the nation is also repeatedly metaphysical properties up to deification (cf. for example the national allegories ) attributed. The writer Ferdinand Bruckner saw this tendency to exaggerate as a central problem, especially in the Austrian self-image:

“Whether there […] a brilliant emperor once resided in Vienna, or whether a pale Mr. Schuschnigg wanted to fulfill“ Austria's historical inheritance obligation ”: there was always an Austrian fiction, a metaphysical justification for why Austrians were born. Simply acknowledging the fact that they are in the world would have been tantamount to officially accepting that the Austrians are one people. Nations need no metaphysical justification. Their existence already answers all questions about the meaning of their existence. "

Even Benedict Anderson sees nations as representation Communities its individuals, "limited and sovereign [...] presented political communities" which had since met even within the smallest nation ever all individuals personally, "but in the mind of each is the presentation of their community exists." For attempts to define different national identities that lead to such an imagined community, cultural, linguistic, historical, religious or ethnic commonalities of the respective population are often chosen. According to Anderson, "communities [...] should not be distinguished from one another by their authenticity, but by the way in which they are presented".

language

After 1945, Minister of Education Felix Hurdes in particular promoted the strengthening of Austrian German , which was therefore derided by German national critics as Hurdestian . In addition to initiating the Austrian dictionary , he also initiated the renaming of the school subject German to the language of instruction, which was later gradually withdrawn. A clearer emphasis on the linguistic independence of Austria was demanded more and more in the course of the consolidation of the Austrian national consciousness . This included both the call for dialectal terms to be increasingly written down as well as the rejection of non-Austrian German words and the associated increased recourse to Austrianism . Austrian German is now widely recognized as an independent variety of the German language.

The attempt to define national independence through linguistic differences is nevertheless difficult and is limited to the standard language. There are major regional differences, especially in the dialect area , for example between the different Alemannic dialect variants that are predominant in Vorarlberg and West Tyrol and the southern and central Bavarian dialects that dominate the rest of the German-speaking areas of Austria. In the constitutional convention of 2005, it was also discussed to emphasize the definition of the state language in Article 8 B-VG as "Austrian German".

A linguistic justification of a nation would make it more difficult to include the Croatian, Hungarian, Czech, Slovak, Romance and Slovene-speaking ethnic groups (recognized minority languages in Austria ) in the Austrian concept of the nation. In addition, language, especially in connection with book printing, is seen as an important initial factor in the nation-building process, but has meanwhile lost its importance.

Culture

Some scholars, especially in the consolidation phase of the Austrian national consciousness, assumed an independent Austrian culture early on, which they set in contrast to German culture in order to emphasize Austrian independence in the cultural field as well:

"From the victory of the Counter-Reformation to Maria Theresa, the character of the Austrian culture was shaped by the Catholic worldview and the Italian baroque, Protestant worldview and French classicism dominated the intellectual life of Germany until the end of Gottsched's dictatorship."

However, Austrian culture has only been a national identification factor since the middle of the 20th century, with the broad concept of culture encompassing both classical and modern music , literature and the visual arts, as well as customs and folk culture. According to Wendelin Schmidt-Dengler , however, Austrian literature cannot be defined solely through Austrian German, but primarily through content and stylistic properties. Schmidt-Dengler found the term difficult to grasp, but to speak of Austrian literature as German literature was ridiculous. This is now viewed as an independent movement, but still interacts with the rest of German-language literature.

Discussions often trigger cultural assets that were created before the nation became a nation - but especially before the state was founded in 1804 - and that are described as exclusively Austrian or German. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , for example, is referred to as a German or Austrian in a number of sources, although neither a German nor an Austrian nation-state existed during his lifetime and the designation German was not yet used in the modern national-ideological sense. A newspaper war broke out between the Austrian Kronenzeitung and the German daily Bild over the question of Mozart's "nationality" .

religion

Although Austria was primarily understood as the Catholic counterpart to Protestant Prussia in the past , a religious definition of the Austrian concept of the nation fails not only because of the secular foundation of the republic, but also because of the lack of religious homogeneity . Many citizens already refer to themselves as "without confession", but in addition to the Catholic majority population, a number of Austrians also profess the Protestant , Orthodox , Muslim or Jewish faith.

Ethnicity

In contrast to the concept of the nation, ethnos is, according to some ethnologists , a primordial bond that is independent of the individual. While an individual can freely confess to a nation, belonging to an ethnic group, independent of his will, is predetermined by the cultural ties and his socialization . Some also assume the existence of an Austrian ethnos. This includes scientific specialist literature - this is how the dictionary of the world population regards the term Austrian as ethnologically occupied from around 1945 - organizations, politicians, the media and government agencies as well as Austrian school books and international organizations.

For Ernst Hanisch the approach to an Austrian is Ethnonationalism a problem of "Reaustrifizierung": "Had but a national identity built on a not sharply defined ethnic group."

Most historians and ethnologists today do not see the term people as a permanent and consistent group of people with common ancestry. The idea of genealogically uniform peoples is viewed as a Nazi myth. The medievalist Jörg Jarnut , for example, considers the term Teutons to be a construction: “The idea of an ethnic unity of the Teutons is historically untenable.” ( Page no longer available ) The historian Herwig Wolfram said: “That there could be no unmixed peoples , Seneca has already deduced logically. ”In addition, according to Wolfram, inaccurate ancestry myths are still adhered to:“ For example, the Bavarians and Austrians still want to be Boier , i.e. Celts, and in Carinthia, as is well known, there are no or only sparsely settled Slavs. " ( Page no longer available )

One problem with the ethnic concept of the nation is that it, like the construction of the language nation, generally excludes other ethnic groups. A common Austrian community of descent cannot be scientifically established, but it is not necessarily implied by the existence of an “Austrian ethnicity”. Compared with other factors, however, ethno-national ideas only take a lower place in surveys when it comes to the question of which characteristics are decisive for being “a real Austrian”. In 2008, 52% of those questioned stated that “descent from an Austrian” was important for this.

Will nation

In connection with the attempt to put the Austrian nation on a scientific foundation, the term “ will nation ” is often used , which is not exclusively about language, culture and ethnic homogeneity, but above all about a “sense of identity and togetherness” among nationals Are defined. Immigration countries such as Canada or the USA , but especially Switzerland, call themselves a nation of will . From there comes an opinion published in memory of the fall of the state of Austria 70 years ago in March 2008: The Second Republic is in a splendid position today. Unlike then, it is not just a state construct, but a prosperous nation of will [...]. For the Austrian author and Germanist Franz Schuh , Austria shows signs of a willing nation. This is characterized by "the unquestioning of the confession" of its citizens.

State nation

Since the independent state system in Austria had a special influence on the development of national awareness, the term state nation is also part of the scientific discourse. The state and the nation of will overlap in that both focus on a culturally and ethnically heterogeneous or outwardly barely delimitable population. However, while the willing nation focuses on the civic commitment to the community, the concept of the state nation aims at the meaning of the community for the citizens. After 1945, the concept of the state nation was mainly represented by the SPÖ , which wanted to distance itself from the return to Austrian history, as promoted by the conservatives. Theodor Körner , the second Federal President of the Second Republic, said of his party's understanding of nationality:

“However, international parlance defines the nation neither as a language nor as a people, but simply as a community of citizens. In this sense, the Austrian people are undisputedly their own nation. […] It must also be understood that the Austrian socialists cannot make the 'good old days' of the monarchy […] the basis of their commitment to Austria, but unconditionally commit to the Republic of Austria that they helped to create. [...] The Austrian socialists are uncompromising in their commitment to the Republic of Austria. Regarding the republic - we would wish that all of the Chancellor's party comrades [ note: Julius Raab (ÖVP) ] would also recognize this part of our common democratic soil without reservation and not precede the word 'republic', as if we were ashamed of it. But the commitment to Austria is uncompromising. The Austrian socialists learned this through bitter experience. Today you are fully committed to the Austrian idea. [...] We are Austrian national. "

However, what speaks against the classification of Austria as an exclusive state nation is that precisely the period in which there was no Austrian state was of particular importance for the nation-building process. In addition, the term state nation ignores cultural identities and rather excludes the presence of Austrian minorities. The authors of the book “The Austrians - Value Change 1990–2008”, published in 2009, see Austria in the field of tension between cultural and state nation. The reason for this is the results of surveys that highlighted the importance of language and culture as well as the bond with the Austrian state.

history

From the Middle Ages to the end of the Holy Roman Empire

Forerunners of the name Austria existed since the early Middle Ages . In 996 he was first mentioned as Ostarrichi , then in the 13th century as "Osterrich". Initially, this designation only applied to the area of the Duchy of Austria , later also to the other Habsburg rule around the heartland of the hereditary lands . At that time neither the ethnic nor the nation concept existed in its current meaning, 'Austrians' were the inhabitants of the hereditary lands as subjects of the house power of the House of Austria (Domus Austriae) , militarily the own troops of the Habsburgs under the red and white red flag of the hereditary lands. According to Friedrich Heer , Vienna became the center of the first - albeit still monarchical and territorial - consciousness of Austria : until modern times, the identification of the individual with society was primarily through the Christian religion and the status of being a subject of a ruler or a dynasty embossed. Linguistic and ethnic identification schemes only played a subordinate role in the pre-modern era. Tradition and identity have arisen through reference to it and its subsequent construction. For the Habsburgs, this concept was later formulated as Old Austria .

Austria, as part of the Holy Roman Empire, was supposed to be elevated to kingship under Frederick II , but this failed when the emperor died. From 1512 it finally became customary to add the addition of a German nation to this empire , primarily to distinguish itself from the French. Emperor Maximilian I wanted to postulate a general interest in the unruly German imperial estates and motivate them to provide money and troops; in his self-portrayal, however, the term “German nation” played no role. The Austrian historian Otto Brunner , himself a Greater German, stated that this nation “cannot simply be understood in terms of the boundaries of German nationality”. Countries such as Bohemia and Italian- or French-speaking areas also belonged to the empire. The phrase Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation largely disappeared towards the end of the 16th century. The constitutional lawyer Johann Jacob Moser described it in 1766 as an "adopted phrase". Only at the time of the Napoleonic Wars and after the dissolution of the empire in 1806 was the term reactivated by Karl Friedrich Eichhorn and used in the context of the awakening national movement. The German historian Karl Zeumer was of the opinion in 1910 that “hardly anyone could ignore the conviction that serious academic historians are no longer allowed to use the expression [Holy Roman Empire, German Nation ' note ] in the way it has been used since Eichhorn and Ficker . Of course, it will take longer before the use of the so learned-sounding and sonorous phrase is dispensed with in popular and school literature. "

It is difficult to speak of a “common German history” for this period in relation to today's Austria and Germany. Rather, it was a question of constant disputes between the imperial estates and the emperor, who mostly came from the Habsburg dynasty. While the German imperial estates were able to successfully repel a state formation aimed at by the emperors from the House of Austria (especially Charles V and Ferdinand II ) and which integrated the entire empire, the Habsburgs succeeded in promoting state formation in their hereditary countries and making this completely accessible to the imperial institutions - like the Reichstag and Kammergericht - to be withdrawn and thus disintegrated from the Reich. A national identity consciousness in the modern sense did not yet exist. While only local ties played a role for the “lower” strata of the population, the elites had different, hardly competing levels of identity in a mixture.

Developments up to the small German solution

In the pre-national age, however, local collective identity patterns already existed, whereby, according to the prevailing opinion today , approaches to ethnic or nationalist politics can only be spoken of from the 18th century. After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire through the resignation of the imperial title by Franz II. In 1806, who founded the Austrian Empire as Franz I in 1804 , and the adoption of the German Federal Act in 1815, efforts within the German Confederation grew into one To convert nation- state. There were plans to integrate Bohemia and Moravia , although only the minority of the population in both countries was German-speaking. Above all, the Wars of Liberation had promoted the patriotic to nationalist currents in the areas of the former empire. Austrian politics, above all the then Foreign Minister Johann Philipp von Stadion , used this mood, but also viewed it with suspicion, since the pan-German movement also stood in opposition to the absolutist self-image of the Habsburgs.

The interest in a German nation-state lay primarily with the leading layers of the bourgeoisie and hardly with the high nobility and ruling houses. This was expressed in the revolution of 1848 , which, in addition to a democratic drive, also had a German national drive influenced by Romanticism . In addition to the bourgeoisie, especially members of student fraternities were involved.

Members of the then Austrian Empire also took part in the National Assembly's meetings in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt (see list of members ). Archduke Johann of Austria , a younger brother of Emperor Franz I , acted as " Reichsverweser " and was thus the first German head of state elected by a parliament .

At the preliminary truce of Villafranca in 1859, Emperor Franz Joseph I tried Napoleon III. , To win Austria for an alliance against Prussia and to achieve the surrender of the Rhineland, with the attributed words: “No, I am a German prince.” (Archduke Johann as all-German imperial administrator and the quote from Emperor Franz Joseph are published in 1905 at the latest the confiscated - and therefore treated in the House of Representatives - issue No. 16 of the Deutsches Nordmährerblatt , where it is mentioned in connection with the engagements of the imperial family in non-German parts of the monarchy.)

For neo-absolutist politics, however, after the suppression of the revolution, the focus was less on national and more on dynastic problems. Until 1866, a monarch from the House of Habsburg was regarded by the southern German states and the kingdoms of Saxony and Hanover as the legitimate head of the “Greater German Solution”, that is, a German Empire including the German-speaking areas of Austria. The question of supremacy within the German Confederation or the empire to be founded finally ignited the conflict in the German war between the great powers Prussia and Austria, the Prussians as attackers with the defeat of Austria on July 3, 1866 in the battle of Königgrätz for themselves and the " small German solution " (excluding Austria) decided.

This date is already referred to by some historians as the time of Austria's departure from the German nation. At this point in time, however, Golo Mann and other authors did not see any concrete beginnings for this development: “The Swiss had become a nation of their own. The Austrians did not [...] As a 'nation' they had to look across the borders to Germany. "

In the year after this defeat, the Austrian empire , which had been a unified state until then , was divided into two halves by means of an equalization in order to come to terms with the Hungarian nobility . The demands of the Slav peoples, especially the Czechs , remained unfulfilled. In 1868 the monarch stipulated that the entire monarchy should be described as the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. In Cisleithanien , the non-Hungarian part of the overall monarchy, the term Austrian continued to be used supranationally: "For all members of the kingdoms and countries represented in the Reichsrathe there is a general Austrian citizenship right" (1867). On the other hand, the kk area was officially referred to as "the kingdoms and countries represented in the Imperial Council" until 1915. Only then was it determined that Cisleithanien should now also be officially designated as Austria.

After the successful campaign against France in 1870/71 finally by the Prussian Prime Minister was made Otto von Bismarck favored creation of a German Empire without Austria (smaller German solution). Wilhelm of Prussia was proclaimed German Emperor by the German princes in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles after Bavaria had given its approval by granting various "reservation rights" (see Kaiserbrief ).

From 1871 until the collapse of the dual monarchy

In the German-speaking population of the Austrian monarchy at the time, especially among the liberal bourgeoisie, the confession of belonging to a German nation had been widespread since the Napoleonic Wars at the latest . After the founding of the empire , Franz Grillparzer wrote :

“I was born a German, am I still one? Only what I have written in German, nobody takes away from me. "

Statements like these clearly show that national and cultural identities at that time were primarily defined through common linguistic features as a criterion for belonging to a people . The standardization of German in language and writing , which took place supranationally, also contributed to this. At the same time, the following quote has also come down to us from Grillparzer:

"I am not German, I am Austrian."

It proves the ambivalence to which the term “Austrian” was subject at that time. On the one hand it served as a self-definition as a special form of the Germans, such as Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria etc., on the other hand as a supranational term for the citizens of Cisleithania and thus to differentiate them from the citizens of the German Empire. The identity structures of large parts of the population were still regionalist at that time, and German nationalism initially remained a bourgeois elite phenomenon.

Despite the monarch's avowal of his German nationality , the bourgeois circles in Austria were among the greatest critics of the Habsburg dynasty, seeing the Habsburgs as the main obstacle to unification with the German Empire. The leading protagonist of a Greater German solution was Georg von Schönerer , who not only rejected the Habsburg monarchy (state and imperial family), but also the state-supporting Roman Catholic religion, against which he initiated the Los-von-Rom movement . This brought him above all conflicts with the Christian Socials , who were considered loyal to the emperor. The call for Austria to move closer to the German Reich finally manifested itself in the Linz program . In the long run, the demand for a complete connection was no longer acceptable to a majority in the German national camp. For the German Radical Party of Karl Hermann Wolf , in 1902 as a splinter group from the Pan-German Association came into being and until the First World War to the hegemonic force in the German national camp was, this was not a priority.

The Austrian social democracy , at that time a cross-national party, tried to achieve reforms in an evolutionary way, but was rejected by the bourgeois-conservative camp and by the emperor , and internally it was not free from nationality struggles. Some of their leading politicians, such as Victor Adler or Engelbert Pernerstorfer , had a German national past.

Austria-Hungary was seen as a supranational entity, but ethnic conflicts increasingly arose. The main trigger for this was the hegemony of the German-Austrians in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy , which was primarily opposed by the Kingdom of Hungary . Otto von Habsburg called the German-speaking subjects of the monarchy the "people of the Reich par excellence".

This was the view of a “circle of patriotic writers” in 1908, who chose Ludwig Sendach's eulogy “Austria's Hort” as the introduction to the two-volume celebratory gift of the same name to the Austrian people for the jubilee of Emperor Franz Josef I in 1908 . It emphasizes with propagandistic exuberance that Austria cannot fall “so long [...] the German songs resound”, “the German sword guards”, “German discipline and customs” prevail, German “male loyalty” and German women rule: “ As long as you are German, Austria, / You cannot fall that long! "

The historian Ernst Bruckmüller confirms this as follows:

“In the Habsburg Monarchy, the German-speaking inhabitants (above all) of the western, Austrian part of the empire, i.e. the majority of the inhabitants of today's Austria, and also the German Bohemians, German Moravians and Silesians as well as German-speaking residents of the other crown lands were simply called 'Germans' . That was just as practical as it was obvious, because the 'others' were Czechs, Poles, Ruthenians, Romanians, Slovenes, Croatians and Italians (we ignore the Hungarian half of the empire here). But the German-speaking Austrians were not only one of eight 'nationalities' of the Zisleithan sub-state of the monarchy, they saw themselves as something else, namely as the state- supporting, if not to say the actual state nation of this sub-state, or even the entire Habsburg monarchy. "

Furthermore, Bruckmüller underlines the diffusion of collective Austrian identities at the time of the Habsburg Monarchy with his thesis that "two German nations" developed towards the end of the 19th century, on the one hand that of the "Reich Germans" and on the other that of the "German Austrians". Their we-consciousness in turn related to several identity factors:

“In the process of the formation of competing linguistic national units within the Habsburg Monarchy, the German-speaking Austrians developed a German-Austrian national consciousness that was characterized on the one hand by an emotional orientation towards the dynasty and statehood of the Habsburg monarchy, on the other hand by an (equally emotional) linguistic and cultural orientation towards" Germanism " . "

For other native speakers, the Austrians were above all the Germans they didn't like; they rejected the so-called “Austrian (Viennese) view”. Based on linguistic and cultural similarities and on political demands for self-determination, independent national identities began to develop among the peoples of the monarchy. The desire for state independence or for a union with nation states existing outside the Habsburg Empire ultimately led, in connection with the military defeat in World War I, to the failure of the multi-ethnic state.

Developments in the First Republic

democracy

After the end of the First World War and the collapse of the monarchy, almost all political forces strove for rapid unification with the German Empire . Article 2 of the law on the state and form of government of German Austria of November 12, 1918 read as follows :

"German Austria is part of the German Republic."

The territory claimed by the state of German Austria essentially comprised the settlement areas of the German-speaking population of the Austrian half of the fallen monarchy. In the Treaty of Saint Germain in autumn 1919, however, the state territory was unilaterally established by the Allies. The later Sudetenland and other German-speaking areas, which had not been under the control of the German-Austrian state government since November 1918, now fell definitively to Czechoslovakia , South Tyrol to Italy and Lower Styria to the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes . Parts of Carinthia were added to the SHS state or Italy. Austria was granted western border areas of Hungary, from which Burgenland was then constituted.

Regarding the identity crisis that ultimately developed from the collapse of the monarchy and the enforced statehood of Austria, Bruckmüller notes:

“The German orientation of the democratic phase of the First Republic appears to be explained primarily by the shock of the collapse of the monarchy, through which the“ Austrian ”component of that consciousness was severely discredited and to overcome it was an escape from the“ Austrian ”and into Germanness and in the - despite Versailles - still powerful German Reich. One could almost speak of Austria's self-abandonment, which was expressed, among other things, in the efforts to name the republic in which the name "Austria" did not appear. "

In fact, social democrats and Greater Germans in particular saw the term “Austria” as a relic of the fallen Habsburg monarchy and sought to eliminate it. Karl Renner had therefore called the new state "Southeast Germany" in his draft of the provisional constitution, which was created several times in October 1918. Suggestions for names such as "Hochdeutschland" , "Deutsches Bergreich" , "Donau-Germanien" , "Ostsass" , "Ostdeutscher Bund" , "Deutschmark" , "Teutheim" , "Treuland" , "Friedeland" or "Deutsches Friedland" were included in circulation. In the end, however, the Christian social politicians who did not want to give up the term Austria completely prevailed with the designation German Austria .

Most politically responsible persons regarded the ban on annexation to Germany as stated in the peace treaty as a denial of the peoples' right to self-determination and therefore rejected it. For example, the Christian Socialist Michael Mayr , who worked on the drafting of the Federal Constitutional Law (B-VG) and later was Federal Chancellor for a short time , wrote in the preamble to one of his draft constitution:

"By virtue of the right to self-determination of the German people and their historical members and with solemn custody against any time limit that is set for the exercise of this inalienable right, the independent states of the Republic of Austria unite to form a free federal state under this constitution."

Even the legal positivist Hans Kelsen , who is considered very prosaic, wrote in the closing words of his book Austrian Constitutional Law :

"Nevertheless: [...] stronger than the course of recent history, which scorns all reason and morality, the product of which is today's Austria, stronger than Austria itself is its wish: to merge with the German fatherland."

On the other hand, the poet Anton Wildgans describes in his poem The Austrian Credo , which was written at that time, the emotional attachment of many of his compatriots to the term Austria after the First World War:

|

|

Even before a federal constitution could be adopted, there were follow-up movements in the federal states. Tyrol and Salzburg held referendums on accession to Germany. Vorarlberg spoke out in favor of joining the Swiss Confederation . Although these efforts were largely supported by the population, the Paris suburb agreements made them obsolete. With the ratification of the peace treaty in October 1919, German Austria adopted the name Republic of Austria prescribed in the treaty . Later attempts at rapprochement between Austria and the German Reich were prevented by the Allies by insisting on the wording of the peace treaties. So they objected to the plan launched in 1931 for an Austro-German customs union.

In 1929, in his speech about Austria to a foreign audience , Wildgans spoke of the Germans of Old Austria who would have formed the new, small Austria, but he emphasized the special historical experiences of Austria and the empathy of the "Austrian people" for the foreign-speaking neighboring peoples with whom he was so long lived in the common state emerged as essential independent character traits. In his poem Where the Eternal Snow is Reflected in the Alpine Lake , which wild goose would have liked to make the Austrian folk anthem, but which Richard Strauss set to music too complicated for this purpose, the poet worked out the characteristics of “Austrian people”. On the other hand, the Berlin Reich Chancellery informed the German diplomatic missions around this time that the use of the term "Austrian people" was being refrained from and that only the German people in Austria could be spoken of.

According to the Austrian historian Helmut Konrad , the idea of understanding Austria as a nation of its own was essentially only represented by a conservative minority, above all Ernst Karl Winter , and by parts of the KPÖ . This position was explicitly formulated in 1937 by the communist Austrian political scientist Alfred Klahr in exile in Moscow . He dealt with the question of the scientific justifiability of an Austrian nation in an article. Klahr refused to regard the Austrians as Germans from the outset and demanded a detailed scientific analysis of the differences between the development of the Germans and the Austrians over the past centuries. Robert Menasse therefore sees the basic research on national theory in the KPÖ-related area as the origin and the basis for the later development of Austrian national consciousness. Anton Pelinka writes:

“[…] Initially […] Winter, in deliberate antithesis to all connection plans, coined this term of an Austrian nation and filled it with the concept of a united front against Hitler from right to left. […] Klahr developed a little later, with consistent application of the Popular Front thesis of the VII World Congress of the Comintern , […] an analogous concept. But Winter was considered an outsider [...] And Klahr was taken seriously within the Communist Party, but not by the Revolutionary Socialists. "

Among other things, Klahr said about the relationship between Austrians and the German nation:

“The view that the Austrian people are part of the German nation is theoretically unfounded. A unity of the German nation, in which the Austrians are included, has never existed before and does not exist today either. The Austrian people lived under different economic and political living conditions than the other Germans in the Reich and therefore developed differently. How far the process of developing into a particular nation has progressed or how close the national ties from common ancestry and common language are, can only be revealed by a concrete examination of his history. "

In connection with the sense of belonging among Austrians in the First Republic, Ernst Bruckmüller speaks of a “fundamental collective identity crisis”. The emergence of the first republic was a process of disintegration, which did not give rise to a feeling of “at home in one's own home” for the Austrian residents. The main obstacles to this were that the new republic did not include the entire German-speaking population of Cisleithania and, above all, that there was no desire for an end to the monarchy:

"Disintegration without a certain desire for it evidently does not create an identity, but at most a" vacuum of identity "into which the demand for connection to Germany flowed as a seemingly logical continuation of the national language consciousness."

Austrofascism

After the dissolution of parliament by the German government under Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss in March 1933. This emphasized in his Trabrennplatz speech in Vienna in the autumn of that year the Germans in Austria. The " Fatherland Front " was created as a political unity movement; from May 1936 it was also to be the only legal party. On May 1, 1934, through the last Christian-social members of the National Council , Dollfuss had a new constitution for a “Christian, German federal state based on estates” passed in an unconstitutional manner .

The government propaganda of the so-called corporate state often spoke of Austria as a “better German state”. The Heimwehr leader Ernst Rüdiger Starhemberg said in a speech:

“I demand from you a joyful commitment to Austria, willingness to make sacrifices and an all-encompassing and compelling love of your homeland. Not just for our own sake, but for the sake of our youth. Our belief in Austria and Austria's future is unshakable. Good Austrian is good German. And this awareness of German is so powerful in us that we know that we are strong enough to feel and act German even then to remain German even if we have to make German history outside the borders of the great German Empire in the future. "

This patriotism, represented by the government , never deviated from the German idea of a nation, despite its strong ties to Austria, and led to competition between two German national images and two dictatorships. Manfred Scheuch writes about the Austrian awareness of Austrofascism:

“And when the Christian Socialists steered onto an authoritarian course and thus pushed a large part of the population into the political sidelines, their efforts to awaken Austrian patriotism with the 'Fatherland Front' were in vain. Firstly, because this patriotism was anti-republican and based on the Habsburg past and a power-conscious church. And secondly, because by professing Austria as the 'second German state', yes, as the 'better Germany' with the Austrians - in contrast to the allegedly only superficially Germanized Prussians - he countered himself as a 'real German'. "

Richard Nikolaus Coudenhove-Kalergi , the founder of the Pan-European Movement , demanded the acceptance of an independent Austrian nation as early as 1934 in a much noticed article. After their birth, he said, the nation-building in Europe would be complete. A circle around the sociologist and Viennese Vice Mayor Ernst Karl Winter also came to the conclusion “that there cannot be an exclusively political patriotism and that, despite all the expediency reasons that one may cite for the existence of an independent Austrian state, this will not last if No Austrian nation corresponds to him. ”In a speech, the Tyrolean Heimwehr leader Richard Steidle called for the defense of Austria's national independence, pointing out that Austria had“ acquired its own national self-awareness and state awareness ”.

The Austro-Fascist system tried to the last to maintain an independent, but “German” Austria. On March 9, 1938, Federal Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg , who came to power after the assassination of Dollfuß by National Socialist putschists in July 1934 , said at an event organized by the Fatherland Front in Innsbruck :

“Now I want and need to know whether the people of Austria want this free and German and independent and social, Christian and some fatherland that does not tolerate party divisions. […] I would like to know, and that's why compatriots and Austrians, men and women, I call on you at this hour: Next Sunday, March 13th of this year, we will hold a referendum […]. "

This referendum had to be canceled under pressure from Adolf Hitler .

The view that Austria was a German state and that its inhabitants were Germans persisted among the Austrofascist rulers until the end. In his radio address on March 11, 1938, the evening before the German troops marched into Austria, Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg announced that he did not want to use the armed forces in order to avoid “shedding German blood”. Schuschnigg concluded his speech with the words: "At this hour I am saying goodbye to the Austrian people with a German word and a heartfelt wish: God protect Austria!"

In a speech on the occasion of the commemorative year 2005, Ulrich Nachbaur , legal scholar and employee of the Vorarlberg State Archives, said that the First Republic was "broken by a lack of self-confidence and internal conflicts". Later, in view of the failure of this state, the sentence was coined, according to which the main reason was that the Austrian democrats were not Austrian patriots and the Austrian patriots were not democrats.

National Socialism

The connection and the consequences

After Austria's annexation to the German Reich and the loss of independence, the term Austria should disappear from the political vocabulary as consistently as possible. So Austria soon became the Ostmark . In order to finally eliminate Austria and any semblance of Austrian consciousness as a political unit, only the term " Danube and Alpine Reichsgaue " was used in the end. The federal states of Lower Austria and Upper Austria were given the names Niederdonau and Oberdonau . In his speech on Heldenplatz in Vienna shortly after the German troops marched into Austria, Hitler only spoke of his “homeland” and the “oldest Ostmark of the German Reich” and avoided the term Austria .

The new rulers organized a referendum on April 10, 1938 on the "reunification of Austria with the German Reich". The vote was preceded by a huge propaganda campaign. Even if the majority of those entitled to vote would probably have voted for the connection, the vote was massively manipulated. The voters were put under pressure to openly cast their votes directly in front of the election commission, and the election results were manipulated. According to official information, the submission achieved approval of 99.73 percent in Austria with a voter turnout of 99.71 percent. In the referendum, around eight percent of the Austrian population was excluded from voting for racial or political reasons.

Shortly after the German invasion, the euphoria about the Anschluss cooled down in some sections of the population. The main reason for this was the fact that Austria and Vienna in particular had a different position within the empire than expected. In the negotiations on the unification of Austria with the Weimar Republic, a special position was envisaged for the Austrian capital. Now, as Renner wrote in the Austrian declaration of independence in 1945, it has been “degraded to a provincial town”. The imperial insignia and the gold treasure of the Austrian National Bank were brought to the " Altreich ". On the first anniversary of the Anschluss, reports from the Gestapo criticized the dwindling euphoria in the population. The invasion of Czechoslovakia was received with mixed feelings in Vienna; 30 percent of the city's residents had Slavic, mostly Czech, roots.

After the Anschluss, the Austrian National Socialists had hoped that they would be taken into account in the upcoming allocation of posts, but were themselves disappointed, as the NSDAP preferred to rely on "Reich German" supporters when filling management positions. The rapid end of mass unemployment due to the overarching armaments economy (see also Central European Economic Day , Armament of the Wehrmacht ) was credited to the regime by many, but the harmonization of all areas of life, the unpopular start of the war in 1939 and even more the foreseeable failure of the Russian campaign from the end of 1941 led to it massive disillusionment. The German political scientist Richard Löwenthal said of the mood among the Austrians after the Anschluss:

"The Austrians wanted to become Germans - until they became one."

When the Second World War broke out in September 1939 , the Austrian men were gradually drafted into the German armed forces. An accumulation of Austrians in the individual troops was systematically avoided in order to prevent social isolation from the soldiers from the "Old Reich". Only among the mountain hunters did the Austrians represent a significant group.

Bruckmüller writes about the connection and its consequences for Austrian awareness:

“The time of the National Socialist occupation had already made the Austrians aware of the fact that Austria was by no means viewed by the Germans (Nazis, entrepreneurs, military) as a 'liberated' country on a par with other areas of the German Empire, but as a colony, their economic One wanted to exploit resources and their people appeared to be useful for the military apparatus and the war economy. Related to this is (secondly) that the Austrians were not 'Germans', but at most second-class Germans. A process of awareness of national peculiarities began (prepared before 1938 by a few intellectuals in minority positions such as, on the left, Alfred Klahr and, on the right, Ernst Karl Winter , Oskar AH Schmitz or Dietrich von Hildebrand ), which has been accelerated since 1945. The result is a clear, albeit not entirely contradicting, Austrian national consciousness. "

The role of the Austrian resistance

In 1943, when the indications of Germany's final military defeat in World War II began to grow and the end of National Socialist rule appeared in sight, some of the politicians of the First Republic who had not fallen victim to political terrorism or who were not in custody began their activities in secret to plan an independent Austria. During this time, the first rethinking of the Austrian identity took place.

The formation of Austrian resistance groups such as O5 played a central role here. The author Ernst Joseph Görlich wrote about the importance of the resistance for the strengthening of the Austrian identity, that this was not in its extent, but in its effect of extreme relevance. The documentation archive of the Austrian resistance estimates the number of Austrians involved in the resistance at 100,000. The historian Felix Kreissler also sees national character traits in the Austrian resistance and grants it a central role in the development of the Austrian nation.

Also in the two major political camps of the First Republic, the Christian Socialists and the Social Democrats, "in Austrians who, to their astonishment, as they themselves admit, noticed that they no longer experience themselves as Germans, but primarily as Austrians" , in the course of 1943 the conviction prevailed that Austria should take its own path again after the end of the war.

The endeavors of German Social Democrats, represented by Wilhelm Leuschner , who presented to Adolf Schärf , to maintain the unification of Austria with Germany after the end of the war, was rejected by the latter. Although Schärf, like large parts of the Social Democratic leadership, had been a staunch supporter of the union before 1933, in the course of the conversation he realized that the situation had changed. To Leuschner he said spontaneously: "The Anschluss is dead. The Austrians' love for the German Reich has been driven out." Only then did Schärf talk about the subject with Renner, Seitz and others: "We have all slowly [...] come to the point that last came to my lips when I was talking to Leuschner. ”Karl Renner, for example, spoke out in favor of the Anschluss in 1938, among other things in a newspaper interview, arguing that although it did not go as planned, in the end that counted factual result.

Lois Weinberger , member of the Austrian resistance and later ÖVP politician, was visited in 1942 by Carl Friedrich Goerdeler , member of the German resistance , who later participated in the attempted coup of July 20, 1944 and was executed for it. He also spoke out in favor of maintaining the connection. Weinberger defended Austria's plan for national independence after the war to Goerdeler.

As in Germany, there were no mass uprisings against Nazi rule in Austria either. Even if the occupiers, who were perceived as Prussian, made themselves unpopular with parts of the population, they waited for the war to end without risking their lives. Even if the Allies were aware of the existence of Austrian resistance, especially through Fritz Molding's contacts in Paris , they did not consider it powerful enough. The Foreign Office assessed the situation in Austria as follows in 1944:

“There is practically no evidence of an organized resistance movement in Austria. You don't like the Nazis, certainly not the Prussians, but the overwhelming majority of Austrians are not prepared to take any personal risk. "

Several scientists, including Felix Kreissler , consider the year 1943 to be the decisive one for the later development of the Austrian nation. In a sense, it marks the turning point that led away from Pan- Germanism and towards the Austrian nation. In the Moscow Declaration in 1943, the Allies declared that Austria had become "the first victim" of Hitler and would be restored as an independent state after the end of the war. Austrian exiles, among others, had influenced this position. However, the Austrians in the country only found out about the Moscow Declaration if they heard " enemy broadcasts " at risk of death. Before and after the Moscow Declaration, the staff of the British and US State Ministries also considered the Danube Federation and the South German Confederation, each including Austria.

Concept evolution and acceptance of the Austrian nation after 1945

After the end of the Second World War, an Austrian national identity emerged mainly in terms of demarcation from the German nation. Regardless of whether the Privilegium Minus of 1156 or the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 was taken as the starting point: most post-war ideas about nations share the view that Austria was never part of Germany or the German nation.

At that time, national consciousness was generally understood to be the type of collective identity that describes the largest group to which a person feels they belong. The transition from a mere Austrian consciousness to an Austrian national consciousness in this sense is mostly assumed from 1945 onwards.

The incorporation of Austria into the German Reich, which was declared null and void from the point of view of international law , ultimately formed Karl Renner's main argument in the largely drafted Austrian declaration of independence:

“In view of the fact that the annexation of 1938 was not, as is a matter of course between two sovereign states, agreed to safeguard all interests through negotiations from state to state and concluded through state treaties, but through military threats from outside and the treasonable terror of a Nazi fascist Minority initiated, abolished and forced from a defenseless state leadership, finally imposed on the helpless people of Austria by military warlike occupation of the country [...] the signed representatives of all anti-fascist parties in Austria without exception issue the following declaration of independence. "

The declaration of independence does not speak of an independent Austrian identity, nor of the active participation of many Austrians in the Nazi regime or of the fate of Jewish Austrians.

However, the first Austrian Federal Chancellor of the Second Republic, Leopold Figl , pointed out in his first government declaration before the National Council on December 21, 1945 that the mistakes of the First Republic were not to be repeated. In this speech, he indirectly identified the Austrian nation as a cultural nation, but at the same time refused to regard it as a mere political invention:

“The Austria of tomorrow will be a new, revolutionary Austria. It will be redesigned from the ground up and will not be a repeat of 1918, 1933, or 1938. […] Our new Austria is a small state, but it wants to remain true to this great tradition, which was above all a cultural tradition, as a haven of peace in the center of Europe. If we repeatedly emphasize our loyalty to ourselves, rooted in our homeland, with all fanaticism, that we are not a second German state, that we have never been, nor do we want to be, an offshoot of another nationality, but that we are nothing other than Austrians, but with all our hearts and that passion that must be inherent in every commitment to one's nation, then this is not an invention of ours, who are responsible for this state today, but the deepest knowledge of all people, wherever they may be in this Austria. "

The state division along the borders of the occupation zones , as it soon occurred in Germany, could be prevented in Austria. Finally, in 1955, the occupation was ended with the State Treaty , which, among other things, confirmed the ban on affiliation. In the same year the Republic of Austria was admitted to the UN and constitutionally declared its " permanent neutrality ". The Austrian policy of neutrality was subsequently also seen as creating identity. Ruth Wodak describes neutrality, alongside the victim myth, as the second mainstay of the Austrian identity discourse.

Promotion of awareness of Austria as an educational concern

The national ideological independence of Austria was also promoted by the authorities of the occupying powers. For example, on August 9, 1945, the Salzburger Nachrichten, which was then published by the American armed forces, published an article entitled “Are Austrians Germans?” In which, among other things, differences between Austrian and German National Socialists were emphasized. In order to strengthen awareness of Austria, the 950th anniversary celebrations for the signing of the Ostarrîchi certificate were held as early as 1946.

At the beginning, however, the Austrian national consciousness was an elite patriotism, which only prevailed in large parts of the population over time.

Despite its usefulness in foreign policy, the national self-confidence that has emerged among Austrians can not only be traced back to their experiences with National Socialism and war, but also to the formation of political, cultural and economic identity.

For historical reflection, a concentration on Austria within today's borders was consciously encouraged. In 1957 the magazine Austria began in history and literature , which was aimed primarily at high school teachers. Past achievements, e.g. B. in the field of scientific research, were now considered limited to Austria: Austria's share in the discovery of the earth appeared in 1949 (by Hugo Hassinger ), in 1950 (supplemented in 1957) a volume of Austrian natural scientists and technicians (by Fritz Knoll ) appeared, and in 1951 published a history of medicine in Austria (by Burghard Breitner ).

The Academy of Sciences in Vienna was renamed the “ Austrian Academy of Sciences ” in 1947 - instead of the place where the academy is located, its reference to Austria was emphasized.

The victim myth

After the end of the Second World War, the idea that Austria was an independent nation also served to uphold the so-called victim thesis . The Austrian side was therefore also happy to feel that it was the first victim of National Socialism and for this reason alone to emphasize statehood.

To support this theory, the Foreign Ministry published a red-white-red book in 1946 , which contained documents from the years 1933 to 1945 and related comments. The book has been criticized by many historians as being tendentious. Ruth Wodak says, referring to Bruckmüller's statements, that “Austria is poor in non-controversial data that are suitable for collective identification: There is no successful revolution, no independence or liberation movement as in other countries where such historical events create identity . This claim could perhaps also explain why the victim thesis has become so important. "

The British historian Gordon Brook-Shepherd describes the connection as “Rape by Consent” (“Consensual rape”) and Erich Kästner thematized the Austrian victim myth in a mocking song by having the national allegory Austria sing:

- “I gave myself up, but only because I had to.

- I only screamed out of fear and not out of love and lust.

- And that Hitler was a Nazi - I didn't know that! "

The victim myth only began to crumble in 1986 in the wake of the so-called Waldheim affair , in which the role of the presidential candidate Kurt Waldheim was at stake during the Nazi era. Above all, Waldheim's statement that he had only done his duty in the Wehrmacht sparked a broad public discourse about the Nazi past of many Austrians. Finally, in 1991, then Federal Chancellor Franz Vranitzky admitted that many Austrians were complicit in the Nazi terror: “There is a share of responsibility for the suffering that, although not Austria as a state, but citizens of this country have brought upon other people and peoples.” This admission made possible the realization of the memorial service project by the then Interior Minister Franz Löschnak in 1992 .

On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the Austrian National Fund, the President of the National Council, Andreas Khol , said in 2005 about the suppression of the victim thesis: “To the extent that Austria became a nation in the consciousness of its citizens, to the same extent the Austrian nation acknowledged that many of its citizens and citizens became perpetrators in the National Socialist injustice state and their republic bears responsibility for it. ”In his speech, Khol also quoted Wolfgang Schüssel , Federal Chancellor at the time, who, in rejection of Austria's responsibility as a state, had said:

“I will never allow Austria not to be seen as a victim. The country was in its identity the first military victim of the Nazis. But I don't want to give the impression that we want to minimize or talk away the individual guilt of many perpetrators in any way. "

The President of the National Council, Barbara Prammer , spoke at a memorial event on March 12, 2008 about the consequences of the victim myth for the victims of National Socialism in Austria:

"[...] after 1945 many [...] saw themselves as victims of economic, social and personal constraints [...] a fiction of history was created; Austria is often only portrayed as a nation of victims. This made it easier to avoid confrontation with the crimes of National Socialism and to ward off guilt. […] Few of the survivors of the concentration camps who returned to Austria were warmly welcomed. The return of expropriated property was refused because they saw themselves as a victim of "foreign tyranny". Those who returned disturbed this self-image. "

patriotism

A particularly enthusiastic national awareness has not developed in Austria for a long time. Ernst Bruckmüller classifies the feeling of Austria in the Second Republic as "more realistic and resigned than enthusiastic and emphatic."

However, new empirical studies show that in the meantime a very pronounced Austrian national consciousness has developed, especially in comparison to other nations. In a survey from 2001, 56% of the Austrians questioned said they were “very proud” of Austria, 35% were “quite proud”. When asked whether they are proud of their Austrian citizenship , 46% of those questioned answered in 2008 that they are very proud, 38% that they are proud of it.

According to studies by the US National Opinion Research Center , Austria ranks fourth behind the USA , Ireland and Canada in an assessment of general national awareness in several countries and received 36.5 out of 50 points. In a poll conducted as part of this research, 83% of the Austrians surveyed said they were proud to be citizens of their country, ranking third behind the USA and Ireland. 64% of those questioned also believed that Austria was better than most other countries.

Anton Pelinka wrote about the development of Austrian patriotism:

“Those were the times when you (when I) as an Austrian patriot could still provoke annoyance - in Austria; when the reference to the Austrian nation still triggered reactions like “ideological freak”; when patriotism did not cover up opposites, but rather uncover them. Those days are over. And that's kind of a shame. Because now they are all patriots, namely Austrian […]. No, good old Austrian patriotism is dead - unfortunately. He didn't mess up opposites, he made them clear. The new patriotism, for which everyone is - or should be, is like opium. It is supposed to replace understanding with well-being; and the often painful analysis through dull warmth. Whoever wants to want it. I do not like it."

Nation awareness and neighborhood

Due to the historical and linguistic proximity to Germany and because of the prevailing view that Austria was part of the German nation, the definition of the Austrian was driven primarily by the distinction from the German concept of the nation. In order to make this demarcation as clear as possible, everything German was and is often viewed as non-Austrian and thus as negative, and the developed national consciousness is projected back into epochs in which it did not exist. However, Austrian nationalism is not only directed against the Germans, but - like all nationalisms - against “the foreign” per se.

On the other hand, Austria has a long history in common with its non-German-speaking neighbors. The Danube Monarchy , which fell apart because of the nationalisms of its peoples, is still having an impact . In this sense, the Czech Foreign Minister Karel Schwarzenberg drew extensive parallels between Austrians and Czechs in 2008 :

“Why should it be any different? We are a people with two languages, with mirror images of prejudices, weaknesses and a past. We're so similar, it's almost grotesque. "

In the same year, the former Czech diplomat Jiří Gruša , head of the Diplomatic Academy in Vienna operated by the Republic of Austria, made a similar statement : "Czechs and Austrians are one nation," said Grusa ironically when asked why the two neighbors could argue so well. If Herder's definition of the nation through language did not exist, then the Czechs and the Austrians would be one and the same nation. Mentally, emotionally and in the way we approach problems, we are one nation. The worst arguments are often in a family. We are a divorced marriage that is now being repaired a bit in the EU. What separates the Czechs and the Austrians? The common character , Jiri Grusa varied a quote attributed to Karl Kraus about the relationship between Germans and Austrians.

Positioning on the concept of nation

The sociologist Gunter Falk sees three positions in principle towards an independent national identity of Austria:

- the negative, German national position,

- the alternative, internationalist attitude and

- the Austrian national position.

There are also regional differences, with some also citing local identities as primary identification factors. Regional identities are still much more important in Austria than in other European countries. In addition to the individual relationship, individual social groups also position themselves in relation to the idea of the nation. The main political forces of the Second Republic can also be classified in the three main positions.

The position of the parties after 1945

ÖVP

The Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) was re-established in 1945 and represented a conscious break with the Christian-Social, but also the Austro-Fascist tradition of the First Republic. Like its predecessor parties , however, it continued to represent the conservative camp. In its first “Programmatic Guiding Principles”, which it formulated in 1945, the ÖVP deviated from the previous German-national course of the Christian-Social Camp, in which, for example, in “schools of all levels”, the “complete penetration of teaching with Austrian ideas” and the “most intensive Work on building the Austrian nation, which must form a strong, proud Austrian state and cultural consciousness ”demanded.

SPÖ

After its defeat in 1934, the Social Democratic Workers' Party of the First Republic split into Social Democrats and “revolutionary socialists”. In order to prevent a division of the workforce after the war, the party was re-established as the Socialist Party of Austria (SPÖ) in 1945, but its programmatic focus was social democratic. The SPÖ also began to deviate from its greater German starting position. In 1926 she had included the Anschluss as a goal of her politics in her party program, but deleted it again in 1933 following the takeover of power by the National Socialists in the German Reich. Although parts of the SPÖ tended to affirm Austria's national independence, individual representatives, above all Friedrich Adler , held on to the fact that Austrians belong to a German people .

Karl Renner described this attitude as “a page that has fallen out and picked up from a long-yellowed political reader” and said in his speech at the opening of the newly elected National Council on December 19, 1945: “From now on, the truth and indestructible reality: Austria will stand forever! “Nevertheless, the SPÖ kept a low profile on the nationality issue for a long time, probably also in order not to distress Adler's supporters. At the latest with the party program of 1972 and the new basic program, however, the acceptance of the Austrian nation also largely gained acceptance in the social democracy.

KPÖ

The Austrian Communists were based on the theory of Alfred Klahr was in 1937 among the first who called for the national independence of Austria. The KPÖ maintained this position after 1945, but remained politically and ideologically dependent on the Soviet occupying power. In 1947 Otto Langbein, who was responsible for the editing of the Austrian dictionary from 1969 to 1973, called for a clear distance from Germanness in the KPÖ party organ "Weg und Ziel" :

“We have to prove to ourselves and to the world in everything and everyone that we are not Germans, that we have nothing to do with Germanness. [...] The German nation, the German culture are for us a foreign nation, a foreign culture. Austria must finally bring itself to the conscious feeling: the Germans do not concern us a hair more than any other people. "

The communists therefore strongly criticized the German national stance of the Association of Independents (VdU) and the Greater German tendencies in the SPÖ. The KPÖ, which had always been a small communist movement compared to other European countries, was finally no longer elected to the National Council in 1959.

VdU / FPÖ

The Association of Independents (VdU) was founded in 1949 as a party of the “ Third Camp ” and represented liberal as well as Greater German and German national concerns. The VdU, which dissolved in 1956 and partially merged into the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) , was thus the most important association of opponents of the Austrian nation becoming. In the Aussee program of 1954 it was said: "Austria is a German state, its policies must serve the entire German people."

After internal party tensions that arose from the Aussee program, there was a severe defeat in the National Council election in 1956. The FPÖ has essentially not abandoned its commitment to belonging to the German people and culture. In the party program of 1997 it is said that “the legal system presupposes that the vast majority of Austrians belong to the German ethnic group.” The third paragraph, however, softens this German national attitude with the following formulation: “Every Austrian has the fundamental right to to determine one's identity and ethnicity in a self-determined and free way. "

In the FPÖ electorate, the German national position now only represents the opinion of a minority ; According to surveys, only 17% of those questioned who declare themselves to be FPÖ supporters deny the existence of an independent Austrian nation. When the FPÖ politician Wolfgang Jung said in 2002 that he would identify himself as a German if you asked him about his nationality, he was also criticized by his own party leadership.

BZÖ

The Alliance Future Austria (BZÖ) did not clearly commit to a commitment to the nation in its 2011 program. There it said, among other things: "We want the protection of the homeland within the framework of the sovereign nation-state, which with its constitution guarantees the democratic participation of citizens in the EU."

As in the style of the FPÖ, from which the BZÖ emerged, the word "home" was often used. As with the concept of the sovereign nation state, it remains open to which area one refers and whether this means national independence of Austria.

Green

The majority of the Greens can be attributed to the internationalist position. For them, the idea of the nation has negative connotations and is historically burdened. They see the collective identity as a reason for exclusion and a threat to individual self-determination. The basic program of the Greens states, among other things: "Heterogeneous interests (for example in the nation state or in the EU state association) cannot be squeezed into the tight corset of a prescribed identity."

The positions of other groups

Monarchists

Monarchist and legitimist circles were and still are critical of the idea of an independent national identity. These are largely pannationalist currents, which are mainly based on the example of the fallen multi-ethnic monarchy. At the same time, they are also in opposition to the affiliation idea, as this would amount to a formal waiver of the restitution of the Habsburgs.

Churches

In 1938 Cardinal Theodor Innitzer was persuaded to support the Anschluss with the Bishops' Conference and to sign a call submitted to him to vote yes in the “referendum” of April 10th. He sent the appeal to Gauleiter Josef Bürckel with an accompanying letter that the bishops had “voluntarily and without coercion” fulfilled their “national duty”, and added the phrase “ Heil Hitler ” to the greeting phrase by hand ! The call was posted with a facsimile of this cover letter. In the autumn of 1938, however, Innitzer's “Christ is our King” sermon for Catholic youth in St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna led to the Hitler Youth storming the Archbishop's Palace; later priests were active partly as soldiers' chaplains, partly in the Austrian resistance against the Nazi regime.

The Evangelical Church in Austria was nationally oriented and welcomed the "Anschluss" almost unreservedly: The unnatural condition that had existed since 1866 has been eliminated [...] We thank the Führer for his great deed.

After 1945, the churches took an increasingly reluctant position on political issues that did not directly affect their moral teaching. Accordingly, they did not openly take sides on the question of nationality either.

Minorities

Since the Austrian identity has developed into an independent national consciousness, the relation to Austria of various German-speaking minorities in Europe has also been discussed. In the course of this, the terms “Austrian minority” and “old Austrian minority” are used by some politicians , parties , interest groups , authorities and the media . These refer, among other things, to German-speaking minorities in Italy , Croatia , Slovenia , Romania or the Czech Republic .

The extent to which these ethnic groups took part in the process of becoming a nation in Austria and how the self-assessment of the minorities concerned is structured has so far hardly been assessed. In addition, terms such as “German, German-speaking, old Austrian and Austrian minorities” are often used diffusely and synonymously without a clear distinction being made.

South-Tirol

For German-speaking young people from the Italian province of South Tyrol , the country of South Tyrol is predominant as the main identification factor. In the course of a social study from 1999, over 79% of the German-speaking young people surveyed said they were primarily South Tyrolean, while this proportion was only around 11% among Italian-speaking people. When asked which area they felt most strongly connected to, 40.6% of young people with German as their mother tongue named South Tyrol, 6.6% Italy, 1.4% Europe and only 0.4% Austria. This is an indication that the South Tyroleans did not take part in the Austrian nation-building process.

Official designations such as “Department of German Culture”, to which several offices belong, or “German Education Authority” speak against participating in the development of the Austrian nation. Officials speak mostly of the German language group or the German-speaking South Tyroleans. Informally, a distinction is usually made between Germans (German-speaking South Tyroleans) and Italians.

Due to the historical, cultural and linguistic ties to the state of Tyrol , the ties to it are emphasized from many sides. The Süd-Tiroler Freiheit exemplarily emphasizes the special reference to Tyrol with the spelling Süd- Tirol .

On the other hand, the social democratic foreign minister of Austria, Bruno Kreisky , in 1960, as part of his engagement before the United Nations, made it important to speak of the South Tyroleans as an Austrian and not a German minority in Italy. In the years that followed, this approach was only pursued by a few leading South Tyrolean politicians, even though it had an important advocate in the Governor Luis Durnwalder, who was in office from 1989 to 2014 .

Slovenia

In the Slovenian census of 2002, 181 people declared themselves to be ethnic Austrians. In 1953, 289 Slovenian citizens were still part of the Austrian ethnic group. In comparison, a total of 499 people declared themselves to be members of the German minority in 2002, compared with 1617 in 1953. Accordingly, the Austrian minority has shrunk by 37% and the German minority by 69% in the same period. No data is available on the exact motives for the German-speaking Slovenes' self-confession to one of the two minorities. As far as the rights of the German-speaking minority are concerned, there have been repeated exchanges between Slovenian and Austrian politicians, especially against the background of the Carinthian sign- off dispute .

Use of terms

The term nation is generally used in two ways. On the one hand in its actual ideological sense, as a collective term for collective identities, on the other hand as an expression to describe the entirety of the population. Statements such as “The whole nation is in mourning” are therefore not to be regarded as being used in the actual sense of the term. Furthermore, the word nation, or the word part national, has found expression in a number of political terms in Austria. Here, too, it should be noted that the term “national” is mostly used more in terms of constitutional law than in the sense of national identity. Examples are: National Council , National Bank , National Library , National Park, National Security Council or National Fund.

The officially binding Austrian dictionary also uses the term “Austrian nation” and refers to it for the words “nation” and “Austrian”. Kreisky - when asked if there was an Austrian nation - said that if there was a national bank, a national library and a national football team, there must be a nation as well.

Although the national holiday fits into the series of above-mentioned terms with more constitutional than national connotations due to its historical date (commemoration of the adoption of the Neutrality Act on October 26, 1955), it is used by opponents to delimit the Austrian national consciousness: They speak from the national holiday to indicate their rejection of the Austrian nation. Görlich also evaluates the national holiday quite ideologically by labeling the rejection of this term: "Anyone who deliberately does not use the word national holiday for October 26th shows what kind of spirit child he is."