Germanic peoples

A group of former tribes in Central Europe and southern Scandinavia , whose identity in research is traditionally determined by language , is called Germanic tribes . Characteristics of the Germanic languages are, among other things, certain sound changes compared to the reconstructed Indo-European original language , which are summarized as Germanic or first sound shift . The settlement area inhabited by the Germanic peoples is accordingly referred to as Germania .

From the turn of the ages , contact with the Romans shaped the Germanic world, just as the development of the Roman Empire increasingly connected with the Germanic world. In late antiquity , during the migration of peoples, there were extensive traits of several Germanic tribes ( gentes ), some of which formed larger associations (see ethnogenesis ), and finally their invasion of the Roman Empire. Some of these groups founded empires based on the ancient Roman model on the soil of the western empire , which perished around the year 476. Elements of the Germanic religion and religious customs were transferred into the accepted Christianity through accommodation , among other things .

This article describes the general history of the Germanic peoples, beginning before the turn of the ages, up to late antiquity and the beginning of the early Middle Ages . The research also sees the history of Scandinavia up to the Middle Ages in a Germanic context. The history of individual tribes , Germanic mythology and Germanic tribal rights are the subject of further articles.

term

Origin and development of meaning in antiquity

The origin of the term Germanoí ( Greek Γερμανοί), Latin Germani has not yet been satisfactorily clarified. The linguistic - etymological origin as well as the exact age of the term remains unclear . In the history of research, linguistic roots from Latin, Celtic and Germanic were discussed. The occasional connection with Germanic * gaizaz , Ger , throwing spear 'is now considered disproved. For phonetic reasons, the derivation of the Latin germānus 'corporeal, real, true', which Strabo suggested , is also considered improbable . Most likely it becomes a Celtic etymology. The roots of Old Irish gair 'neighbor' or gairm 'scream' are considered, from which the naming motifs “the neighbors” or “the screamers” result.

In ancient times, the German name was an ethnographic generic term for a large group between the Celts and the Scythians . So it was mainly a question of naming certain peoples by others and only to a lesser extent and probably only secondarily a self-designation of the Germanic peoples for themselves. The peoples settling on the right of the Rhine remained before Caesar's Gallic campaigns (58-52 BC. ) largely outside the horizon of ancient observers and, when they were found out, were initially mistaken for Celts, or at least not explicitly distinguished from them. The oldest historical reports on Germanic cultures come from encounters with the Greeks and the Roman Empire; own written documents such as B. Runic inscriptions , however, can only be found after the turn of the century. The reports of the ancient authors on the Teutons are often not based on their own observation, but on hearsay. The Greek traveler Pytheas from Massalia reported as early as 330 BC. About the countries around the North Sea and the peoples living there. The East Germanic Bastarnen invaded from around 200 BC. BC to the southeast into what is now Eastern Romania and were from 179 BC. In the fighting of the Macedonians and other peoples on the Balkan Peninsula . Around the year 120 BC The Cimbres , Teutons and Ambrones moved south and inflicted some serious defeats on the Romans ( Cimber Wars ).

The Fasti Capitolini from the year 222 BC are sometimes used as the oldest evidence of the popular name . Cited. There is talk of a victory of Marcus Claudius Marcellus "de Galleis et Germaneis" ("over Gauls and Teutons") at Clastidium . However, this mention of the German name can also be a subsequent description in the context of the Augustan fasting editorial team. The first unequivocal use of the German name can be found around 80 BC. At Poseidonios of Apamea . The term initially only referred to a small tribal group in the Belgian-Lower Rhine area, whose area was originally on the right bank of the Rhine. Poseidonios describes that these "Germanic peoples " ate parts of roasted meat as their main meal and also drink milk and unmixed wine, and thus corresponded in a certain way to the barbarian topos of his time.

Caesar reported in his Commentarii de bello Gallico in 55 BC From the Belger tribes of the Remi , Condrusi , Eburones , Caerosi , Paemani and Sequani , who settled on the left of the Rhine , that they called themselves Teutons, and called these tribes (always following the information of the Remer allied with him ) as Germani cisrhenani , but not the Atuatuci (now also considered Germanic) - whom he considered descendants of the Cimbri - and only with reservations the Ambivarites . The name cisrhenani ("left bank of the Rhine") suggests that the tribes named in this way were distinguished from the Germani on the right bank of the Rhine .

In the course of Caesar's war report, the Teutonic concept is filled in further up to its comprehensive explanation in the Germanic excursion of the sixth book (53 BC). Here Caesar also explicitly uses an expanded Germanic term by declaring the Rhine to be the cultural divide between Gauls on the west bank and Germanic tribes east of the river and calling all land east of it Germania . What led Caesar to identify all peoples east of the Rhine with Germanic tribes is controversial in historical research. An explanation could result from the general's intention to accept the Rhine as the national frontier, postulating such a deep gap between Gauls and Teutons, and thus to present his military work as the "conquest of Gaul".

In this case, the geographical distinction between Celts and Teutons would also have been politically motivated, as it could help to consolidate Rome's claim to rule over all areas on the left bank of the Rhine. While Caesar had previously called different groups, who understood themselves as Aquitans , Celts and Belgians , uniformly Gauls , he now transferred the Germanic term to different ethnic groups on the right of the Rhine. At that time, however, the Rhine did not represent a clear cultural divide, as Celtic groups to the east and Germanic groups to the west of it, as can be seen from Caesar's report. From an archaeological point of view, only the area of the Celtic oppida can be delimited to the north and east. From then on, Caesar's definition also had a differentiating effect from an ethnographic point of view.

Before Caesar it was assumed that the Celts lived north of the Alps in the west and the Scythians in the east - separated from them by the river Tanaïs (today Don ) . Cicero knew the Germanic term Caesar in 56 BC. Not yet. But already for Pomponius Mela (around 44 BC) the southern border of the Germanic area was the Alps, the western border the Rhine , the eastern border the Vistula and the Sarmatian area , the northern border the sea coast. Also Pliny the Elder calls in his Naturalis historia (77 n. Chr.) Germans in the Alps. Strabo still described the Germanic peoples in his geography (written between 20 BC and 23 AD) as a people similar to the Gauls. The procession of the Cimbri, Teutons and Ambrons was also seen as a prelude to the Roman-Germanic confrontation. At the time of their appearance, the Cimbri were not yet identified as Teutons. It was not until 100 AD that Plutarch coined the term “Germanic”, also for the North Sea Germanic tribe, which had previously been mainly considered to be Celtic. The Roman historian Tacitus reports in his ethnographic writing Germania (98 AD) on the terms Germani and Germania he used :

“The term Germania is new and only appeared some time ago. Because the first to cross the Rhine and drive out the Gauls, the current Tungrians , were then called Germanic tribes. So the name of a tribe - not a whole people - gradually gained wide acceptance: first all [peoples on the right bank of the Rhine] were called Germanic peoples after the victor, out of fear of him, but soon they too called themselves that after the name once had come up. "

These messages from Tacitus about the origin and location of Germania agree with the information handed down by Caesar from the Belgian Remer from the time of the Gallic War . Accordingly, the tribes on the right bank of the Rhine were first referred to by the neighboring Gauls in a more comprehensive sense as "Teutons". This expansion of the German name is mostly attributed to the fact that the Gauls perceived the eastern invaders as strange or different and tried to differentiate themselves from them. The Romans would then have adopted the German name from the Gauls.

A Germanic Identity in Antiquity?

The tradition of a mythical genealogy comes from Tacitus, according to which the Teutons traced back to Tuisto , his son Mannus and his three sons, who gave their names to the tribal groups of the Ingaevonen , Hermionen and Istaevonen . The Marsi , Gambrivii , Suebi and Vandilii have added a variant . The self-assignment of tribes to a common ethnic group, as it was shown in this mythical genealogy, suggests a sense of togetherness of some kind.

In historical times there were different ethnogeneses in the Germanic area. This tendency towards unification emanated from different centers and was often stimulated from the outside rather than the inside. The infiltration of geographical marginalized groups on the Elbe and in Jutland as well as in southern Scandinavia also played a role. According to Reinhard Wenskus , the Suebi in particular promoted an ethnogenesis of the Germanic peoples in Central Europe. The dominance of the Suebi, whose tradition and appearance were decisive for the ethnographic perception and description of numerous Germanic tribes in the ancient world, also had an external effect. According to Wenskus, the fact that it was not the Suebian name that prevailed but the older one of the Teutons can be traced back to the confrontation of the Suebi with the Romans, who broke the political power of Suebism. Since the end of the 5th century, the external effect of the Suebenname was partially transferred to the Goths , so that the expression "Gothic tribes" became common for numerous, mostly East Germanic peoples. For the Germania magna , however, it remained with the Germanic term, in addition to which the wandering East Germanic tribes under their own identity - as Goths, vandals , etc. - appeared.

In recent times, research has increasingly emphasized the instability of ethnic identities, especially in antiquity, and also questioned the Germanic concept, which supposedly came from the national thinking of the 18th and 19th centuries . “Teutonic” (like “ barbarian ”) is just a foreign name that says more about the Greeks and Romans than about the groups and individuals denoted by the terms. Occasionally there is even a demand that Germans and Germanic not be used at all in a scientific context.

Modern Germanic term

The modern Germanic concept is based on the concept formation of the ancient writers, which was taken up again at the latest in the age of humanism . Although Tacitus already included parts of Scandinavia under Germania, the general expansion of the Germanic term to Scandinavia is a later development, which is likely to have been based primarily on linguistic and ethnographic observations. The Swedish reformer and historian Olaus Petri assumed that Swedes and Germans had a common origin in the 16th century. In the late 18th century the idea of a historical, ethnic and linguistic togetherness between the Nordic countries and Germany had become a common belief among scholars. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz wrote in his Unpredictable Thoughts regarding the practice and improvement of the German language (posthumously 1717, reprint 1995, p. 22) that everything the Swedes, Norwegians and Icelanders praise about their Goths is also ours; these peoples would have to be taken for nothing more than North Germans. Even Johann Gottfried Herder shared this view in 1765 in a review on the introduction to the history of Denmark historian Paul Henri Mallet.

At the same time, the humanistic Germanic concept was brought together with the romantic popular concept and, via the “ Volksgeistlehre ”, led to the idea of a continuity between ancient Germanic and modern Germans. The progress of linguistics in the early 19th century made it possible to link this popular term with the language family now titled “Germanic” . The modern-archaeological Germanic term was also based on this linguistic Germanic term: Because the "folk spirit" is also expressed in its material creations, archaeological find types were then assigned to certain cultural groups if continuous settlement could be proven and this was compatible with the ancient sources, as noted in particular by Gustaf Kossinna . In the late 19th century, Germanic research experienced a further boom thanks to the need for a national cultural identity determination, led to important findings, but also to an increased recourse to the assumed continuity of history from the Germanic peoples to the German Empire of the 19th century, which finally ended in the Germanic myth of ethnic movements and then National Socialism . Numerous statements and concepts from this older Germanic research have therefore become questionable in the meantime.

In more recent times, the uniform Germanic term has partly broken down into various Germanic terms. There were several reasons for this: On the one hand, the identification of archaeological find types with uniform ethnic groups could no longer be maintained. Even the justified language tree does not yet establish an essential unity of "Germanic peoples". The Germanic terms peculiar to the various disciplines (historical research, linguistics, archeology) are therefore no longer necessarily congruent today, even if closer cooperation, for example, between archeology and linguistics, especially under the sign of topo- and hydronymics , is viewed as a desideratum . The Scandinavians are only Germanic in the field of Germanic philology , but not in historical research on the Roman Empire. On the other hand, the only people who, according to ancient tradition, referred to themselves as Germanic peoples, namely the Caesarian Germani cisrhenani , are perhaps not Germanic peoples, but Celtic assimilated Belgians . Even if the representatives of the prehistoric Jastorf culture are named as Germanic peoples , the ethnographic term Germanic peoples is transferred to periods in which it did not yet exist - in both ancient and modern forms.

However, the dissolution of the classic Germanic term, which ultimately goes back to the peculiarities of the Germanic tribes observed by Celts and Romans, is not without controversy in the current research landscape. As a consensus of historical research, the distinction between a general Germanic term, shaped by ancient ethnography and modern linguistics and history, and the cultural identities expressed in historical sources in the sense of ethnic self-confidence , which are justified in the historical representation, appears today . The source language concept of ethnicity can also do more justice to the low persistence of the tribes and their migration in late antiquity. The character of the tribes is thus reduced to communities of descent , which are reflected in traditional kernels and lore about genealogy and origin of their own tribe.

language

The Germanic languages belong to the western group of Indo-European languages . The Germanic language in its original form emerged from western Indo-European through the first or Germanic sound shift (see Grimm's Law and Verne's Law ).

Outsourcing order and "relationships" (not only) of the West Indo-European language groups Balto-Slavic, Germanic, Celtic and Italian remain controversial. For every close two-way relationship there are supporters and opponents. Celtic borrowings in Germanic lexicons are based on cultural contact during the Iron Age around and before 500 BC. In particular, these concern the word material from the areas of domination, trade and production of goods. With the expansion of the Roman Empire, the Latin language began to have a lasting effect on the Germanic.

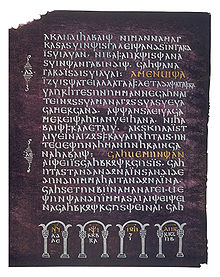

The oldest single Germanic language that has been comprehensively documented in writing is Gothic . The linguistic evidence from the very short and sometimes difficult to interpret runic inscriptions or previously recorded from personal names, place names and other terms in ancient sources, some of which can be determined earlier, consist, in contrast to the Gothic, of individual, unrelated mentions.

font

Self-written Germanic evidence began around 200 AD with the oldest Umordian runic inscriptions. The runes were mainly used as cultic symbols, which is evidenced by the very short and formula-like designs and sounds in weapons (lance tips, swords) or fibulas . The most famous writing carriers are the monumental Scandinavian rune stones . The names of the individual runes have been handed down through rune poems .

The essential early transmission of, for example, historical information, be it things of ancestry or other, took place orally, and in this regard through the price song . From this the later tradition of the heroic saga developed, when a writing system based on the Latin was developed to enable a noteworthy literature ( Old Norse script ). The "signs" described by Tacitus in Chapter 10 of Germania , in connection with the Losoracle, were probably more symbols used than runes in the sense of written characters. Nevertheless, some of these have been integrated into the runic alphabets.

The first actual form of a developed Germanic written language are the Gothic scripts. Originally, like other tribes and peoples, the Goths used the common runic writing and carved it into objects made of wood and other materials ( ring by Pietroassa ). The Gothic bishop Wulfila developed an alphabet for the Christian mission of the Goths, which was composed of Greek, Latin and runic characters. In terms of time, he anticipated the development of the Nordic writing system, from the same conditional circumstances. The runic script as a monumental script is inadequate for a written language that makes literary comprehensive text content legible and comprehensible for a local and supraregional group of recipients in a sustainable and meaningful way. His vernacular translation of the New Testament, along with other Gothic sources, forms the basis of comparative research on Germanic writing and linguistic quality through the extensive Gothic vocabulary presented. The individual names of the Gothic letters are passed down through the so-called Salzburg-Vienna handwriting.

Genetic results

In 2009, Scandinavian researchers found the mtDNA H; J; T in three samples from a passage grave near Gökhem, southern Sweden, but the mtDNA groups U4 / 5 / 5a; H1b in 19 samples from the Mesolithic pit ceramic culture in Gotland. With a large-scale comparison, they believe they have proven that today's Scandinavians, despite having lived in the neighborhood for a thousand years, are not descendants of the Mesolithic pre-population, but predominantly the Neolithic immigrants of the Funnel Beaker Culture (from 4300 BC). However, this thesis contradicts the distribution of Y-DNA haplogroups that has since been determined. While the bearers of the funnel beaker culture left little traces on today's population, the proportions of the Y-DNA haplogroup I1, which has been proven to be mesolithic, are particularly high in Scandinavia at around a third. However, the majority of the population belongs to the Y-DNA haplogroups R1b and R1a, which are identified by paleogenetics with the carriers of the Indo-European language who immigrated in the Neolithic (Corded Ceramic culture). In this respect, the Germanic languages can also be traced back to prehistoric migration, but the population associated with them seems to have arisen from a mixture of the Mesolithic pre-population with corded ceramists.

Way of life of the Teutons

|

|

This article or section was due to content flaws on the quality assurance side of the Germanic project entered. This is done in order to bring the quality of the articles from this topic to an acceptable level. Please help to fix the shortcomings in this article and join the discussion ! |

Historical descriptions of the social, economic and political life of the Germanic peoples are mostly based on the texts of Caesar and the Germania of Tacitus, which must, however, be placed in the time and context of the authors' intentions. But some traits have gained general acceptance in science. The results of archeology offer essential knowledge today .

settlement

The Teutons lived in relatively small settlements. From the size of the burial places (cremation graves) of the Teutons, archaeologists conclude that the size of settlements was around two hundred people. There were also the elaborate state graves of Lübsow with body burials. The settlements rarely developed according to plan. The so-called cluster villages in Germany and other countries of the Germanic cultural area are a legacy of this to this day . The villages were often surrounded by a kind of fence, rarely by a real palisade . Only in the border regions to the Roman Empire were the villages protected and guarded with ramparts or palisades when hostilities and mutual attacks began.

It is known from excavations that the Germanic peoples lived in timber frame houses . Since, in contrast to stone houses, the wood rots over time, only the archaeologically verifiable post holes give a rough indication of the structure of the houses. The most common type was the three-aisled nave , six to eight meters wide and often more than twice as long, in individual cases over 60 m. Under its roof it housed the family as well as all semi-free and slaves as well as the animals, which were only separated by a wall. The main advantage of this was that the animals helped to heat the house in the cold winter months. The living room had no further partitions, in the middle there was a fireplace. The smoke could escape through an opening in the roof. The Germanic houses probably did not have windows.

Although the most important burial method at the turn of the century was cremation with subsequent urn burial, numerous bog corpses are also known, which are linked to very different circumstances of death. From around 300 onwards, the proportion of body graves increases sharply, although cremation remains common in some tribes.

society

The people were divided into free, semi-free (servants) and without rights (prisoners of war, slaves). At certain times there were meetings of the free men ( Volksthing ), at which important decisions were discussed and made. B. the choice of a leader. Only these and the Gaufürsten had the right to propose to the Volksthing. Society was organized on a patriarchal basis and the household had a special place in it. The power of the leaders only extended to the master of the house, but everyone living in the house was subject to him, and the supervision of the clan offered protection from arbitrariness.

According to Tacitus , monogamy was common. This made the Teutons an exception among the barbaric tribes of antiquity.

development

Grave finds indicate an increasing social differentiation in the first centuries AD. Prominent persons were increasingly buried unburned with rich additions, while urn burial was otherwise still common. The communities were shaped by followers and army kings and outlasted political alliances. The semi-nomadic way of life did not allow for stable royalty.

In the course of time, a special leadership class developed among the Germanic tribes, also recognizable by the spreading burials with grave supplements. The cult communities of the earlier imperial era were replaced by following associations, which could include several tribes. Army kings came from leading, respected families, but their rule was often limited to a single person. It was a factual position as a result of achievement (especially in combat) and self-achieved power. There were also divided kingships in the east, either with several tribes as a whole, as with the Cimbri and Alemanni, or a sacred kingship in addition to the political one , probably with the Lugians . A monarchical kingdom did not emerge until the early Middle Ages with the emergence of Germanic-Romanic kingdoms. The first mention of a king Maelo for the Sugambres in Augustus is considered uncertain. The first historically known army king of Germanic peoples is Ariovistus . His rule was not limited to a single tribe. At the turn of the ages the Suebi formed a large association, which was also described by Tacitus. Little is known about the social conflicts associated with the formation of the Germanic tribe, and the contrast between Arminius and Marbod can only serve as an example:

- Arminius and Marbod

- The Cheruscan Arminius († 21 AD) and the Marcomanne Marbod († 36 AD) were both of noble descent and pursued the same goals with regard to Rome, especially the independence of their tribes. Both had got to know the Roman culture intensively. Marbod was in Rome for a few years and was in the favor of Augustus . After his return he became the tribal leader of the Marcomanni . Arminius and his brother Flavus were commanders of Cheruscan units in the Roman service and had Roman citizenship . Arminius was a Roman knight ; the Cherusci had voluntarily submitted to the Romans. In the period that followed, the conflict with the Romans also split the Cheruscan ruling class. Arminius married Thusnelda against the will of her father Segestes . There were mutual sieges. Segestes made a pact with Varus and Germanicus, Arminius' uncle named "Inguimer" with Marbod.

- For both military leaders, noble descent was a necessary prerequisite for advancement to the rank of army king , but not sufficient on its own. In the given historical situation military successes against the Romans were necessary and both had the necessary knowledge of Roman military organization. Arminius achieved military success in 9 AD by defeating the three Roman legions of Varus and was also able to assert himself against the attacks of Germanicus in 14-16 AD. Marbod also had an army of presumably 70,000 foot soldiers and 4,000 horsemen, against which Tiberius raised twelve legions in 6 AD. Only a Pannonian uprising prevented the direct confrontation. After negotiations, a peace was made “on an equal footing”, which immensely strengthened Marbod's military prestige . After the end of the Roman threat, Arminius in particular could only maintain monarchical power if he fought against Marbod. In the year 17 AD there was a battle, Marbod withdrew, lost its military prestige, two years later its kingdom through Katwalda and had to ask for asylum from the old enemies. That it was not a conflict between tribes also shows that Inguimer fought on Marbod's side. Finally, Arminius, whose power was growing too great, killed his own relatives.

economy

The Teutons were mainly sedentary farmers or transhumant cattle breeders , but, contrary to popular belief, they rarely went hunting . They were mostly self-sufficient. In addition to agriculture and livestock farming, there were also craftsmen such as blacksmiths , potters and carpenters . The wheel has been known since Indo-European times. There were even two words for it in the Germanic dialects ( old Germanic * raþą , from German Rad , next to * hwehwlą , from which English wheel ), perhaps to distinguish the original disc wheel from the innovation of the spoke wheel . The Germanic peoples knew nothing about money, their trade was limited to pure natural produce . As with the Romans, the main object of value was cattle. The meaning of the English word fee , fee ', originally' cattle ', testifies to this to this day .

Barley played a special role among the field crops . Different types of wheat , rye , oats and millet were added - depending on the region. The broad bean was mainly grown in the North Sea coast , as well as peas , flax and industrial hemp . Horticulture was also practiced; Fruit growing probably not. Wild fruits were also collected, for example acorns , various berries ( blackberries , raspberries , forest strawberries ), sloes and wild herbs such as spörgel , which could be found in the stomachs of some Germanic bog bodies. Honey was from wild or captured wild bees -Völkern collected beekeeping in the modern sense, there was probably not.

Mainly cattle were bred, as well as sheep, pigs, goats and poultry as well as horses, dogs and cats. The Teutons also knew how cheese is prepared. The Germanic languages had their own word for soft cheese, which lives on in the Scandinavian languages in the word ost ('cheese'). The Latin word caseus (<German cheese ) was later borrowed for hard cheese .

The simple plow was known for a long time, and a share plow was also used occasionally. Likewise were harrow , spade , hoe , rake , sickle and scythe in use. The Teutons regularly left the fields fallow, and they knew about the benefits of fertilization. Grain was mainly eaten in the form of porridge; only the upper class could afford bread until the Middle Ages.

The rural settlements were also the area of craft activities. The processing of leather was the responsibility of the men, while textiles were produced by women ( spinning and weaving ). Specialized craftsmen - who were still farmers - worked as carpenters , joiners , turners or carvers . It was also iron , nonferrous metal , bone and clay processed. Supra-local manufactories or craft businesses were rare. There is no evidence of a well-developed road network or movement of goods on wheels or by ship. However, Roman luxury goods can be found all over Germanic territory. Conversely, amber , furs and blonde woman's hair, which was very much appreciated by Roman women , were probably exported. Roman money was in the possession of many, but was not used for monetary transactions. Its own coinage is only known from post-ancient times.

According to the latest findings, a kind of iron and steel "industry" is said to have developed near what is now Berlin . The steel produced there is said to be of high quality and mainly exported to the Roman Empire. Shipbuilding was also highly developed, as the Hjortspringboot and the Nydam ship show.

The general productivity was much lower than that of the Romans. There was famine, and many Teutons suffered from malnutrition, which led to a relatively short life expectancy . The health of the Teutons was often poor; Joint diseases and intervertebral disc damage were common.

Pre-Christian Religion and the Change to Christianity

Germanic religion

The religion of the Germanic peoples as a whole is a decentralized polytheistic religion related to local cult centers, across the time and cultural spaces of the individual Germanic peoples and tribal groups . It therefore seems sensible to start from the diverse, regionally different cults rather than from a unifying conceptual pattern. In addition, for methodological reasons, one cannot assume a constancy of religious cults; rather, the political and cultural conditions to which the individual tribal groups were exposed and to which the respective testimonies can be assigned must always be taken into account (especially in the course of the migration of peoples ).

Fundamental characteristics of the Germanic religion can be traced back to the Indo-European religion , which was developed through comparisons with other historical religions ( India , Greece , Rome, Celts) . A subsequent influence could have resulted from the cultural and economic contact with the Celts , Balts , Slavs and (later) also the Romans . The religious studies classification into the North Germanic, South Germanic and separate Anglo-Saxon cults is based on the general sources of written and archaeological evidence and is conditioned by historical developments and events.

Sources for the reconstruction and determination of the Germanic religion can essentially be assigned to three groups:

- Historical reports, legal texts: In addition to the records of ancient and late ancient historians ( Germania des Tacitus, Getica des Jordanes ), various medieval mission reports and ecclesiastical prohibitions and penances such as Christian law in Gulathingslov , the indiculia , legal fragments such as B. the Lex Salica , and additions such as to the Lex Frisionum , the old Saxon baptismal vow .

- Archaeological finds: such as cult and sacrificial sites and the so-called “princely graves” including inventory from Scandinavia and Western Europe. In particular, the finds from excavations on former sacrificial moors and lakes can provide information where written sources are silent or, if ever available, are lost. Of particular importance are: Thorsberger Moor , sacrificial moor from Oberdorla / Niederdorla , Nydam moor , moor find from Vimose .

- Philologically developed sources from language and formed language such as poetry and inscriptions (runic texts): The high medieval literatures of Northwest Scandinavia, Iceland and Norway are the main written sources, especially the sagas and the collection of the Song Edda and the Prose Edda . Short fragments of verses and texts like the Merseburg magic spells , sources based on names like place names. Inscriptions on archaeological finds such as on the bow brooch from Nordendorf , the bracteates and rune stones as well as Gotland picture stones .

The transition from the hunting society to the peasant culture and later the conversion to the Christian religion was fundamentally formative for the Germanic religious history. In the roughly two thousand year period between these epochal caesuras, the Germanic religion as such with its regional differences was relatively stable in its main features. From prehistoric times, finds in sacrificial moors and Bronze Age and Iron Age burial mounds reveal a pronounced cult of the dead and ancestors through the dumping of urns or ceramics with remains of organic content. Other votive offerings are jewelry and goods of everyday use. These finds include anthropomorphic pole gods , figures made of roughly worked wooden beams, such as the Braak couple of gods . By working out the primary gender characteristics, these figures were made clearly recognizable as male or female. A term for "God, deity" from later periods, Ase , goes back to the common Germanic word * ansuz , pole, beam '. The assignment to a certain deity of both sexes, known by name from later times, is not possible, except for a certain fertility cult through the gender typing in connection with hierogamy .

The cohesion of the Germanic tribes in historical times was primarily based on a common god and ancestor cult and common sacrificial acts. Sometimes different tribes came together for common rites and thus confirmed their alliance ( Nerthus cult ). In general, however, the religious acts of the Germanic cultures were very diverse, so that gods, as in comparative polytheistic systems of the Mediterranean region, have both different names and different attributes. As in other Indo-European religious systems, the possibility of henotheism is also considered in the religious practice of the Germanic peoples . Among the gods, the best known are Odin (Wodan), Thor (Donar), Tyr (Ziu) and Freyja , which are also reflected in our weekday names today . The South Germanic deity Nerthus (linguistically a neuter, but explained in Tacitus as Terra Mater , Mother Earth) probably corresponded to the Scandinavian god Njörd male. A transcendental understanding of God was probably alien to the Germanic peoples and only developed late in the confrontation with Christianity, as evidenced by northwestern Nordic sources.

Temple buildings like those of the Romans were rare. The gods were mostly worshiped in clearings, in holy groves and on holy waters or moors, sometimes with human sacrifices, but usually with animal sacrifices. These sacred places were separated from the mundane environment by enclosures, accordingly in natural places such as groves that these forests were cultivated and thus a visible separation was effected (wattle fences made of wood sticks). In the Anglo-Saxon settlement area and in southern Germany during the Roman period, immigrant Teutons took over places of worship from the displaced or assimilated Celtic pre-population and the rest of the population. For the Migration Period and the continental area as well as for the Viking Age for Scandinavia, temple buildings or places of worship with a certain constructive substance can be confirmed or inferred from written sources and the vocabulary (cf. the temple of Uppsala ).

The special term for the act of sacrifice is Old Norse blót (also used in variants in Old English and Old High German) with the meaning of 'strengthen, swell'; there is no linguistic connection to the term blood and in the figurative sense of a bloody victim. The offered sacrifices were primarily offered as supplication and thanksgiving offerings. Sacrifice was made individually in the private cult, but also collectively, then also on fixed occasions during the year such as in spring, in midsummer or in autumn and midwinter. In the case of the sacrifice, which was specifically intended for a deity, on the one hand the idol was symbolically "fed", on the other hand, through the consumption of the sacrificial meal - consisting of the cooked sacrificial animals - the sacrificial community had a share. Weapons and other military equipment (presumably from defeated enemies) were also offered at these locations. It is noticeable that sacrificed weapons were previously made unusable. Some of these objects are of high material and ideal value (swords, but also jewelry, fibulae ), which reveals the cultic-ritual reference (fountain sacrifice of Bad Pyrmont). Human sacrifices are documented in part from historical times in ethnographic literature, such as the sacrifice of a slave in the Nerthus cult, which Tacitus describes. The archaeological findings show that, statistically speaking, human sacrifice was very rarely practiced. The following also applies to the bog bodies found in northern Germany and Denmark, which are often associated with human sacrifices: Only a small part of the approximately 500 finds surely indicate a cultic background (see Grauballe-Mann ). In connection with human sacrifice, a conditional cultic anthropophagy has been proven, which refers to the animistic traits of the Germanic religion.

Another term for sacrifice, or the act of sacrifice, was Old English lāc (from ancient Germanic * laikaz , cf. Nordic leikr , Gothic laiks ) with the meaning 'play, dance, fight', seems to suggest that the cult activities are accompanied by ritual dances or processions or were initiated. There is no evidence of an organized or specially marked priesthood for the early historical period. At that time, sacred acts were performed by the heads of families and clans. In the course of the Roman Empire and during the Great Migration Period, priestly structures became apparent, but they were still strongly private. In this regard, Anglo-Saxon and Icelandic documents serve as evidence, such as for the Icelandic Goden . There were female cult personnel corresponding to the female deities. These also included female seers.

The cultic-ritual religious spectrum also includes magic, the magic by Losoracles, as already described by Tacitus, with the use of runes as a medium, as well as runic magic itself, which is shown in the runic poems and runic alphabets ( Abecedarium Nordmannicum , Tiwaz ) , and runic formulas as inscriptions on bracteates such as auja “luck” and laukr “ leek ” (as a magical plant). Spells that have been preserved such as the Merseburg magic spells or Old English spells such as the Canterbury Charm still show the old layers or echoes of Germanic religiosity. Magic and spells could fulfill an apotropaic , damage-defending as well as a salvific and salutary function, but also serve to curse and bring harm and disaster. Consecrations, speeches within the magic spells or in runic inscriptions often have a reference to Thor in the north, on the continent in the second Merseburg saying and on the Nordendorfer rune bar also or only Wodan is mentioned.

Christianization

A monographic overview of the history of Christianization of the Germanic peoples is missing so far. This story has to be seen in three major courses that differ in space and time:

- the spread of Gothic Arian Christianity in the 4th to 6th centuries,

- the Christianization of the Frankish Empire from the end of the 5th to the early 9th century and that of the Anglo-Saxons from the end of the 6th to the 7th century,

- the Christianization of Northern Europe in the 10th and 11th centuries.

The Goths were the first to come into contact with Christianity in the form of Arianism on the Lower Danube and in the Crimea . The derogatory external name Arian - after the Alexandrian presbyter Arius († 336) - denotes a position that arose around 350, which was supposed to convey in the disputes over the doctrine of the Trinity and which was temporarily (in the eastern part of the empire up to 378) officially valid in the Roman state church. On the one hand, it was accepted by the so-called Kleingoten Wulfilas , who resided in the empire , for whom Jesus Christ was in contradiction to the doctrine of pure Arianism, and also by the Terwingen (Visigoths). Shortly before the invasion of the Huns in 375, a rudimentary ecclesiastical organization was built near the Terwingen with Roman support. Wulfila became one of the first Visigoth bishops.

The Wulfilabibel is to be seen in a similar context . In contrast to the Western Church, which tied worship to the Latin language, the Eastern Church was ready to use the vernacular in the liturgy. The translation of the Bible into Gothic is not to be equated with medieval translations of biblical texts that were used for edification and instruction. The Gothic Bible was a liturgical book, the language of which remained closely linked to the original. A provocative feature of the Eastern origin of the Gothic Arian Church in the West was the rebaptism of transgressing non-Arian Christians.

The suppression of pagan religion was seen as a threat to the social order and there were 350 and 370 persecutions of Christians . With the western migration of Christianized Teutons (Goths, Vandals, Burgundians, Lombards) and the founding of empires, Arianism also spread in the - otherwise Catholic - western half of the Roman Empire. However, not all Germanic tribes were Christianized, so that with the collapse of the Roman Empire, the spread of Christianity also suffered a setback.

The Franconian Empire was Christianized from the cultural overlap between the Rhine and Loire . Already Clovis I was baptized, to secure the influence of the Catholic Church. From the 7th century onwards, Christianization also spread to the peripheral zones and neighboring countries of the Franconian Empire and ended with the conquest and incorporation of the Frisians and Saxons . From the end of the 7th century, Anglo-Saxon forces were also involved in the mission. The missionary work of Anglo-Saxon England began with different traditions from the continent and Ireland . The Christianization of the north was carried out by German and English forces and played a decisive role in the formation of the royal power from the end of the Viking Age .

The missionary work began with the political leaders. The acceptance of Christianity opened up new possibilities for religious legitimation for them, which were first fully developed in the Visigoth Empire in the second half of the 7th century in the form of the anointing of the kings . The novel combination of royal church rule led to the spatial delimitation of the church districts through political rule and contributed to the late Roman particularization of the western church. This development began in the last third of the 7th century a. a. by the “model of the Rome-oriented particular church” reversed.

For Christian missions, the religion of the Teutons, like the Hellenistic-Roman religions, was a demonic blindness that prevented people from finding their God-given destiny. The missionary work pursued on the one hand the goal of integrating the whole political association into the church organization and on the other hand the elimination of pagan cults. Baptisms carried out on a large scale without adequate preparation served for admission into the church, and the Christian religion replaced the old one as a new cult to be observed. In the Carolingian era, the rejection of the devil that preceded the baptismal vows was expanded to include the renunciation of pagan gods and cults. In the Lex Saxonum of Charlemagne, certain pagan customs ( burning of witches , cremation of corpses , human sacrifice, etc.) were threatened with the death penalty. Private pagan cults were fined. The claim to sole validity was first enforced in public space and the political and social functions of the pagan cults were taken over. This functional continuity also had an impact on the development of Christianity. The term Germanization of Christianity was discussed in research in this context .

Visual arts

The Germanic cultural world was relatively poor in images. It was not until the 5th century AD that scenes and figures from mythology were depicted on gold decorative discs. In the younger imperial period, fibulas designed according to animal shapes were adopted from Roman models. Boars and deer were particularly popular. Bronze sculptural cattle figures were also known, albeit rarely. Of course, little can be said about wood carving. The imitations of Roman animal images were developed into an independent Germanic animal ornamentation over time.

The Germanic tribes

Importance of the tribes

The tribes were an essential element of the political and social order in Germanic territory . As a settlement community, a tribe had a certain settlement area on which members of other ethnic groups could also live, such as in conquered areas. The tribe had a unified political leadership and represented a legal community. There was also of course a common language, religious rites and a sense of identity, the clearest expression of which was a myth of common ancestry. In fact, tribes were not uniform and stable structures, but always affected by mixing, new formation, migration, decline and the like.

For the first time, detailed descriptions of the Teutons can be found in Tacitus . It describes a fairly uniform Germanic culture in an area roughly from the Rhine in the west to the Vistula in the east and from the North Sea in the north to the Danube and Moldau in the south. In addition, there are the Germanic settlement areas in Scandinavia - not described by Tacitus. Tacitus states that the Germanic tribes are divided into three groups and that there are numerous tribes that do not fit into this classification. According to Tacitus, the individual tribes differ according to their places of worship. The Germanic tribes at the turn of the ages were probably primarily cult communities . This subdivision can also be assigned to archaeological groups.

Since the 2nd century, major tribes have appeared as the most important actors in the Germanic world. They became aggressive opponents of the Roman Empire and bearers of the empires of the people who migrated. They intertwined in different ways with the Mediterranean high culture and ended the relative unity of the Teutons in favor of separate developments. The German name disappeared from the ancient sources and was replaced by the names of the great tribes with their own traditions. They determined the events of the Migration Period and formed the basis of European history of peoples and nation states. The investigations by Wenskus analyzing this process represent the current state of research on this topic. It was a process of concentration arising from alliances, which had political and military impact as its goal. At the same time, there was an increasing differentiation of social stratification. The formation of rule on a personal basis, land, people and booty gains on the one hand and instability of the results on the other hand was dependent on close exchange with imperial and cultural realities in the Roman sphere of influence. Profound political and social changes were a prerequisite for stable political forms.

There is a fundamental difference between the great tribes of the West (Franks, Alamanni) and the gentes of the East (Goths, Vandals, Herulians, Gepids). The great tribes of the west are only attested in the 3rd century, while the gentes of the east initially eluded ancient perception. Their migration associations did not form on the periphery of the empire, but far in the hinterland. The border neighbors of the Roman Empire were then integrated on these trains.

Tribes at the turn of the ages

The settlement areas of the Germanic peoples in the first century (see map) can be divided into:

- North Sea Germans (at Tacitus Ingaevones ): Fishing , Chauken (which later become part of the Saxon tribe ), Frisians , warning .

- Rhine-Weser Teutons (perhaps to be linked with the Tacite Istævones ): Angrivarians , Batavians , Brukterer , Chamaven , Chatten , Chattuarier , Cherusker , Sugambrer , Tenkerer , Ubier , Usipeter . According to the Northwest Bloc hypothesis, these peoples were Germanized later. From the tribes residing on the Rhine, the large Franconian tribe emerged in the 3rd century . On the other hand, the tribes on the Weser, like the Angrivarians and the Cherusci, joined the Saxons.

- Elbgermanen (perhaps with the Tacitean Herminones link): From the Elbe German group - consisting of Hermunduri , Lombards , Marcomanni , Quadi , Semnones , Suebi and perhaps the Bastarni - went in the 3rd century, especially the large tribe of the Alemanni out. In addition, by mixing with other tribes and ethnic groups, the Marcomanni formed the major tribe of the Bavarians , the Hermunduren that of the Thuringians . A part of the Suebi crossed the Rhine together with Alans and Vandals 406 ( Rhine crossing from 406 ) and immigrated with these 409 to Hispania . There they formed the kingdom of the Suebi in the northwest, which formed the basis of the later state of Portugal . The Lombards, after which Lombardy is named, also accepted other Germanic groups into their tribe, first establishing an empire in Pannonia and in 568 after conquering Italy .

- North Germans : The North Germans or Baltic Germans living on the Jutian Peninsula and in Scandinavia - Tacitus calls a tribe of Suionen - are grouped together for linguistic reasons. The Danes , Swedes , Norwegians and Icelanders later emerged from them. Archaeologically, the North Germanic peoples are divided into the East and West Nordic groups. The fishing rods and the jutes form a transition area to the North Sea Germans .

- Oder-Warthe-Teutons : Burgundy , Lugier , Vandals are assigned to the Przeworsk culture (in southern Poland) in archaeological terms .

- Weichselgermanen : The Bastarnen , Gepiden , Gotonen , Rugier , Skiren are archaeologically assigned to the Wielbark culture (Willenberg culture ), whose predecessor was the Oksywie culture (Oxhöft culture ). After the Wielbark culture expanded into the area south of the Baltic Sea, it shifted to the southeast, where it merges into the Chernyakhov culture of the 2nd to 5th centuries. These archaeological finds may reflect the migration of the Goths .

Late antiquity and the Great Migration

The large Germanic tribes that became known in late antiquity did not yet exist at the time of Tacitus, or at most only as vague names. Franks, Goths, Burgundy and the like a. m. emerged as large tribes only in the centuries after the turn of the century. This development remained hidden from the Roman and Greek ethnographers for a long time, so that there are hardly any descriptions in the historical records. The diversity of over 40 tribes (lat. Gentes ) at Tacitus was reduced to a few, which in antiquity were counted as "new" peoples to the previous ones. As smaller associations or as ethnic groups that joined the major tribes or formed sub-tribes, were still u in late antiquity. a. the following tribal names mentioned: Warnen , Angling , Jutes , Juthungen , Rugier , Heruler .

The major associations formed in late antiquity include the Alamanni , Burgundians , Franks , Goths , Gepids , Lombards , Marcomanni , Saxons , Thuringians , Anglo-Saxons and Vandals . The marcomanni, for their part, became part of the Bavarians in the 6th century .

Alemanni

The Alemanni are mentioned for the first time among the tribes who, after 260, occupied the Decumatland ( Agri decumates ) on the right bank of the Rhine, which was abandoned by the Romans . At this time the Alamanni were a mixture of tribal groups of the Semnones , Burgundians , Rätovarians , Brisigavians and the like. a. m. Accordingly, the name could originally have meant “all men, people”, “noble men, people in the real sense” or even “descendants of Mannus ”. The Alemanni were tolerated by the Romans because they recognized the Rhine as a border. It was not until the middle of the 5th century that they - now known as the Alemanni - extended their settlement area to areas on the left bank of the Rhine - as far as Champagne . This led to a conflict with the Franks and the northern territories were lost to them after the Battle of Zülpich (Latin Tolbiacum) in 496. In the 7th century, the Alemanni expanded into northern Switzerland.

Burgundy

The East Germanic Burgundians settled at the turn of the times according to Pliny in the area between the Oder and Vistula. From the 2nd century onwards they moved west and settled the Lausitz and eastern parts of Brandenburg. A century later tribal groups reached the Main Valley and at the beginning of the 5th century the first empire was founded in the region of Worms and Speyer . The Burgundians came into more intensive contact with the Roman Empire and also converted to Christianity.

Francs

The Franks were formed from a loose combat group of Chamaves , Salians , Chattuarians , Ampsivarians , Brukterer and other tribal groups. Raids in Gaul are mentioned from the middle of the 3rd century. Frankish mercenaries were settled in Roman services in northern Gaul. The Salian Franks received as foederati settlement area in Toxandria . This settlement expanded and included the region between Liège and Tournai in the 5th century . On the Lower Rhine, Ripuarian Franks founded a principality with Cologne as its center.

Goths

The Goths probably developed as a tribal association in the area of the Vistula estuary . In any case, they are occupied there at the turn of the century. Statements about the further origins of the Goths remain problematic: the tribal legend ( Origo gentis ) handed down by Jordanes , according to which the Goths are supposed to come from Skandza (Scandinavia or Gotland), cannot be proven archaeologically, especially since the Goths were probably composed of polyethics. After 150 their settlement area slowly shifted towards the Black Sea.

Longobards

The ancestors of the Lombards initially settled in the area of the Lower Elbe. Later the first groups moved along the Elbe to Bohemia and neighboring areas. At the time of the Marcomann Wars in the second half of the 2nd century, the Lombards crossed the Danube to Pannonia. There they were joined by other Elbe Germanic tribal groups. They also received influx of Germanic populations from Thuringia. By the middle of the 5th century, these groups developed their own ethnic profile and were first mentioned in 488 as Lombards.

Marcomanni

The marcomanni first appeared in the army of Ariovistus . Their original settlement area was on the Main, but under the pressure of the Romans, shortly before the turn of the century, they migrated to Bohemia under the army leader Marbod . There they formed the center of a tribal union . In the Marcomann Wars , the Romans were only able to stabilize the northern border of their empire with great effort. In the centuries that followed, the Marcomanni continued to push south. It was last mentioned in the 4th century.

Saxony

The Saxons probably formed in the 3rd century, but possibly not until the 4th century from older tribes of the North Sea Germans. The earliest undisputed mention comes from Emperor Julian from the year 356. In the 5th century, the Saxons divided into the Anglo-Saxons who migrated to England and the Old Saxons remaining on the mainland . A century later, the Old Saxony ruled large areas of the North Sea coast. At the same time the pressure of the Frankish Empire increased in the west and that of the Slavs expanding into the Elbe area in the east.

The conflict with the Frankish Empire led to the Saxon Wars (772–804) under Charlemagne . During this time, Old Saxony was divided into the three tribes or armies of Westphalia , Engern and Ostfalen . After the forced Christianization , this division was replaced by counties . It was not until the 13th century that the tribal law Lex Saxonum , which has since been further developed, was recorded in the Sachsenspiegel . On the other hand, there is no continuity between today's Saxons in the Free State of the same name and the historic Old Saxons of the early Middle Ages, as the Saxon name was only transferred to these Germanized landscapes in the Middle Ages through various dynastic shifts.

Thuringian

After the withdrawal of the Huns , the Thuringians established a kingdom, which was subjugated by the Franks in 531 . Northern Thuringia (roughly today's Saxony-Anhalt to the left of the Elbe) was then partially settled by the Saxons , as were Hesse , Swabia and Frisians . The presumably rather sparsely populated area between Saale and Elbe in today's Free State of Saxony, however, could not be held against the invading Slavs . The Slavic conquest in these areas takes place in the late 6th century.

Vandals

The Vandals had their original settlement area in the region between Oder and Warthe in the area of the Przeworsk culture . The tribal group was divided into the sub-associations of Hasdingen and Silingen - which may have given the region the name " Silesia ". In the 2nd century some tribal groups migrated to the Carpathian arch and the Tisza plain .

Wars and the formation of Germanic empires

The contact with the Romans led the Celtic cultures neighboring the Germans to the threshold of high culture before they were conquered and Romanized. The Romanization was z. T. so comprehensive that z. B. the Celtic languages in the area of what is now France disappeared.

The Teutons did not form a common cultural unit at the time when they inherited the Celts or Gauls in the role of the northern neighbors of the Roman Empire. They retained their independence, although there was also an intensive exchange between the Romans and Teutons.

The confrontation with the Romans helped the Germans to achieve a “Germanic” identity. In the period that followed, there were different attempts to participate in Roman culture. Often it was only about the acquisition of material goods that were peacefully appropriated through trade or gifts or through warfare through robbery and plunder. Later came the participation in power and the appropriation of Roman territory. These endeavors varied from tribe to tribe, but all Germanic cultures strove to leave their original barbaric existence behind and to reach a higher level of social and state order. In the concrete historical situation, this resulted in a constant conflict between Romans and Germanic peoples and it ended in the west with a success of the Germanic peoples, while the east of the Roman Empire was able to avert this threat.

The march of the Cimbri, Teutons and Ambrons

Around 120 BC BC Cimbri , Teutons and Ambrons started south. The cause is not clear: The historical sources report a storm surge in Jutland , because of which the inhabitants left their homeland. However, it is now believed that it was more due to famine due to climatic changes.

Around 113 BC The Germanic tribes met the Romans. In the following battle (also known as the " Battle of Noreia ") the Romans escaped the complete annihilation of their troops only through a sudden thunderstorm, which the Germanic peoples interpreted as a warning omen (rumble) of their weather god Donar .

Around 109 BC BC, 107 BC BC and 105 BC There were several more fights between the Romans and the Teutons in which the Romans suffered a defeat each time. Only after the Germanic tribes had split into two groups did the Romans succeed in 102 BC. To defeat the Teutons and Ambrons, 101 BC. The Cimbri.

- Detailed description: Cimbri

Ariovist and Caesar

The breakthrough of the Cimbri and Teutons through the then still Celtic low mountain range led to the shaking of the Celtic power in central and southern Germany, so that later other Germanic tribes, in particular Suebi tribes , were able to invade Hesse and the Main area . Under their leader Ariovistus they settled from 71 BC onwards. Partially settled on the Upper Rhine. Other groups invaded Gaul, but were caught by Caesar in 58 BC. Beaten and thrown back behind the Rhine.

In the 1st century BC The Roman conquest of Gaul by Caesar made the Germans direct neighbors to the Roman Empire. This contact led to constant conflicts in the following time: Again and again there were attacks by the Teutons on the Romans. In return, Caesar led in 55 and 53 BC He carried out punitive expeditions against the Germanic tribes, during which he had a spectacular bridge over the Rhine built in just ten days. These expeditions were primarily demonstrative in nature and did not lead to a permanent Roman presence on the right bank of the Rhine. Caesar recognized the Rhine as the borderline between Teutons and Romans.

Drusus and Tiberius - advance to the Elbe

The Rhine border did not come to rest in the following years either. The Roman Emperor Augustus therefore decided to move troops to the Rhine that had previously been stationed in Gaul.

The Rhine border nevertheless remained uncertain, whereupon Augustus changed his tactics: He intended to extend the Roman Empire to the Elbe (see also the Augustan German Wars and the History of the Romans in Germania ). Between 12 BC BC and 9 BC Chr. Led Drusus , stepson of Augustus, several campaigns against the Germans by and subjected the Frisians , Chauken , Brukterer , Marsi and chat . Despite the Drusus campaigns , very few Germanic tribes really got into permanent Roman dependency. After Drusus in late summer 9 BC Died in a fall from his horse on the way back from the Elbe, his brother Tiberius led the campaigns in 8 BC. BC successfully ended. In the year 1 AD an uprising broke out with the immensum bellum , which could only be ended by Tiberius in the years 4 and 5 AD. The Romans began to found representative Roman cities east of the later Limes , for example in today's Waldgirmes in Hesse. The Latin name of this settlement is as little known as the Latin names of the forts in Haltern , Anreppen or Marktbreit am Main.

A last great campaign in the year 6 was supposed to smash the empire of the Marcomann king Marbod in Bohemia . He was not an opponent of Rome, but valued his independence. A smashing of his empire would probably have been the keystone of the Roman subjugation of the Teutons. Two large Roman marching columns moved from Mogontiacum up the Main and the Vienna area to the northwest. But the operation had to be canceled because of a surprising, large uprising in Pannonia , today's Hungary.

The Varus Battle

After the resistance of the Teutons seemed broken, Publius Quinctilius Varus was commissioned to introduce Roman law and levy taxes in the areas east of the Rhine. As governor, he was also commander-in-chief of the Rhenish legions. Varus, who had previously acquired the reputation of a brutal and corrupt administrative specialist in the Roman province of Syria , soon turned the Germanic peoples against him. He had opponents of the occupation punished with all the severity of Roman law. The taxes he introduced were also felt by the Teutons as deeply unjust, as they only knew such a tax for unfree people.

Under these circumstances, the Cheruscan prince Arminius , who had Roman civil rights and knighthood , managed to unite several Germanic tribes. Arminius took advantage of the trust that Varus had in him and lured him into an ambush. In the following battle (called " Varus Battle " or "Battle in the Teutoburg Forest") the Romans lost three legions (around 18,000 legionaries, plus around 2,000 to 3,000 additional troops). According to the traditions of Suetonius , Augustus is said to have exclaimed: “Quinctili Vare, legiones redde!” (“Quintilius Varus, give me the legions back!”). The Roman attempt at conquest failed in the year 9. After that, Germania remained little influenced by Roman culture until the Great Migration .

The Roman-Germanic relations after the Varus Battle

Under Germanicus , the Romans undertook further forays across the Rhine border between 14 and 16 AD ( Germanicus campaigns ). Whether these were punitive expeditions or the continuation of the Roman expansion plans is controversial.

In the following years, there were repeated armed conflicts between Teutons and Romans: In the year 29 the Romans put down an uprising of the Frisians who had been friendly to the Romans . In 69 even troops from Spain and Britain had to be called in for reinforcements in order to put down the revolt of the Batavians ( Batavian Uprising ) under the leadership of Iulius Civilis .

In 83 Emperor Domitian decided to move the Roman border between the Rhine and the Danube further north. After the end of the Chat Wars , the Romans began to build the Neckar-Odenwald-Limes , which was connected to the Alblimes in the south by the so-called Sibyllenspur, the Lautertal-Limes , around the borders between Germania (the " Barbaricum ") and the secure Roman Empire. During the same period the provinces Germania superior (Upper Germany) and Germania inferior (Lower Germany) were created.

The latest research from around 1995 onwards suggests that the Neckar-Odenwald-Limes was not created as early as 83/85 under Domitian, but only around 98 under Emperor Trajan . Above all, even after more than a hundred years of research, there is still no reliably dated Roman find from the Neckar-Odenwald line before the year 98, be it an inscription, a military diploma or a dendrochronologically datable wood find. In addition, the Neckar-Odenwald-Limes fits in with other facilities from the time of Emperor Trajan in military terms, while similar parallels are missing for the time of Domitian.

Around 122 the Roman-Germanic border under Emperor Hadrian between the central Neckar and the Danube near Eining was moved about 20 to 40 kilometers to the north. One of the last Roman expansions in Germania, the shift of the Neckar-Odenwald-Limes by around 25 kilometers to the east under Emperor Antoninus Pius , can now be dated back to 159.

The Marcomannic Wars

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, two decisive changes took place on the right side of the Rhine: On the one hand, the Germanic tribes united to form large tribes, on the other hand, the pressure of different tribes on the Roman borders increased more and more.

In 167 the Marcomanns , Quads , Longobards , Vandals , Jazygens and other tribes invaded the Roman province of Pannonia , triggering the Marcomann Wars (167 to 180). In a total of four campaigns, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius defeated the Germanic peoples using all the forces of the empire. In the very unreliable Historia Augusta it is mentioned that the Romans planned to establish two new provinces; whether this corresponds to the facts is uncertain. In any case, this would have secured the apron of the Italian peninsula in a north-easterly direction based on the Gallic model.

Many historians see the Marcomannic Wars as the harbingers of the great migration of peoples . The increasing population pressure on the Roman borders was probably triggered by the migration of the Goths to the Black Sea and the Vandals towards the Danube. The causes for this emerging migratory movement of Germanic tribes could not yet be clarified. B. Famine.

Between the Marcomannic Wars and the Great Migration

With the Marcomann Wars 166-180 under Marcus Aurelius , the conflicts between Teutons and Romans had acquired a new quality. When Marcus Aurelius died in 180, the Teutons were defeated, but not finally defeated; the success was only temporary. However, Mark Aurel's son Commodus returned to Augustus' defensive policy and concluded peace treaties with the Teutons. The forces of the Roman Empire were also exhausted and the devastated provinces had to be restored.

The renunciation of an expansive policy against Germania under Augustus, which concentrated on securing the borders of the Roman Empire, was no longer able to cope with the new requirements. The alliances with individual tribes did not last, as a stable kingdom as a reliable contact did not yet exist. Even the Limes was not enough as a control instrument to stop the incursions of enormous peoples that often recur every year. In addition, the empire fell into a serious crisis, which modern scholars call the Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century : Most of these soldier emperors only stayed on the throne for a short time, while the pressure from the large gentile associations on the Rhine and Danube on the one that steadily increased on the Euphrates through the Sassanid Empire on the other side. The necessary separation of the army into a part for border security and another mobile reaction force did not take place until around 260 under Emperor Gallienus . The main motive for the Germanic invasions was settlement in the Roman Empire, but the empire could not or would not fulfill this wish. There was an interplay of incursions, looting, land grabbing and later usurpations .

In December 2008 it became known that a Roman battlefield from the 3rd century had been discovered near the municipality of Kalefeld in southern Lower Saxony . 1800 mostly military finds were registered. The Roman coin finds show that the battle of 235 took place. The archaeological finds substantiate the reports that have long been known to specialist science, according to which Roman military operations took place in the upstream border area in the 3rd century.

Migrations and founding an empire

The Germanic tribes, which migrated widely at the time of the Great Migration, belonged primarily to the East Germans - e. B. the Burgundians, Gepids, Goths, Longobards and Vandals. The founding of the empires, however, did not last; the East Germanic languages are extinct today. The tribes living west of the Elbe - z. B. the Franks , Saxons and Angles - were comparatively sedentary. The same goes for the northern Germans, who only developed extensive migration activities under different conditions in the Middle Ages at the time of the Vikings . Their languages ( West Germanic languages and North Germanic languages ) have been preserved and developed to this day.

During the time of the Great Migration , Germanic tribes founded empires in North Africa, in what is now France, in Italy, on the Iberian Peninsula and migrated to Britain . The Teutons mostly did not know any administrative state in the Roman or today's sense. The empires of the Germanic tribes were organized in a similar way to the Union of Persons , but Roman administrative patterns were often adopted. The members of a tribe or tribal association swore allegiance to their king and were thus bound to the kingdom. The "state" (whereby the modern term of statehood must not be taken as a basis) was not defined by a spatial extent, but by its people and their position in relation to the ruler. Therefore the empires were strongly connected to the respective king, and the death of the king often also meant the fall of the empire.

However, numerous Germanic tribes (individually or in groups) also entered Roman services and then fought against their old tribesmen. Many of these Teutons rose in the Roman military, with the Germanic army masters sometimes playing an inglorious role, especially in the Western Roman Empire . Others, however, were quite loyal to the emperor (such as Stilicho , Bauto or Fravitta ). While in the Eastern Roman Empire the emperor was finally able to gain control over the Teutons, in the West it was only possible to rule with them. At the latest after the death of Aëtius , the Romans completely lost control of the Germanic tribes who settled on the soil of the empire.

Burgundy Empire

After the retreat of the Romans, the Burgundians crossed the Rhine together with the Vandals in 406 and settled as Roman allies in Mogontiacum ( Mainz ), Vicani Altiaienses ( Alzey ) and Borbetomagus ( Worms ). The area was contractually guaranteed to them. After an incursion into the Roman province of Belgica in 435, the Western Roman army master Aëtius destroyed the Burgundian empire with the help of Hunnic auxiliaries - the memory of this event was preserved in the Nibelungen saga until the late Middle Ages . The remaining Burgundians were resettled by Rome in the area of the Rhone Valley and later founded a new empire there, which was incorporated into the Franconian Empire in 532 and formed a separate part of the empire there alongside Australia and Neustria .

England

After the collapse of the Rhine border in 406/407, the legions were withdrawn from Britain and the Roman presence on the island ceased completely. The Romano-British population recruited Anglo-Saxon mercenaries for protection. Groups of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes settled in the eastern part of the island and partly expelled the Celtic population, which was pushed further and further west over time. By the end of the 7th century, the Anglo-Saxons had subjugated most of the island and were able to maintain their rule against the later Viking incursions until England was conquered by the Normans in 1066 .

Franconian Empire

As early as the beginning of the 4th century, Franks (later also Sal Franks ) had been settled as federates at the northeast end of Gaul . At the end of the 4th century there were repeated fighting between Franks and Romans (see Marcomer ). After the death of the Western Roman army master Aëtius , the 436, the Burgundy Empire destroyed and 451 in the battle of the catalaunian plains the Huns stopped, the area was West Rome no longer controlled practical. After the collapse in 476, in the north of Gaul in the area around Soissons, there was a residual Roman empire under the governor Syagrius , the son of the army master Aegidius . 486/487 the Salfranken under the Merovingian Clovis I defeated Syagrius in the battle of Soissons . This shifted the border of the area controlled by the Franks to the Loire . Clovis, who at first was just one of several small Franconian kings , eliminated the other sub-kingdoms. He saw himself in the continuity of Roman rule, took over the Roman administrative institutions, converted to the Catholic faith and secured his influence over the Church. Military victories in 496 and 506 against the Alamanni and 507 against the Visigoths in the Battle of Vouillé contributed to the further expansion of Frankish rule. The policy of the Frankish Empire continued to be hostile to the last independent Germanic gentes . The feudal system developed from the gift of conquered property by the king . In the early 6th century (after 507) the Latin collection of popular law, the Franken Lex Salica, was created . As Neustria , the empire of Soissons becomes part of the Franconian empire, which was the decisive great power in Central and Western Europe until it was divided in 843 in the Treaty of Verdun .

Goths

Around 150 to the middle of the 3rd century, the Goths extended along the Vistula and Dniester to the Black Sea . Around 290 the Goths separated into Terwingen and Greutungen ; both are not completely congruent with the later West and Ostrogoths . In southern Russia, the Greutungen established an empire, little is known about its size and internal structure. The Terwingen moved into Dacia , which was abandoned by the Romans under Aurelian , and settled there.

The Goths were often in conflict with the Romans, but were never subjugated and even defeated a Roman army in 252. By the invasion of the Huns from the Asian steppes around 375 AD, the empire of the Greutungen was destroyed or fell to the Huns. The Greutungen moved west and settled in what is now Hungary. From then on, they were under the arm of the Huns and took to the field in 451 in the battle of the Catalaunian fields against the Visigoths and Burgundians.

In 488 the Ostrogoth King Theodoric moved to Italy with the Ostrogoths that had now formed and defeated the Germanic ruler Odoacer there . Theodoric thereupon founded a new Ostrogothic empire in Italy, which however perished soon after his death.

The Terwingen, on the other hand, had withdrawn from the Hunnic grip and in 376 fled across the Danube into the Roman Empire. There they were settled, but rebelled soon after, which led to the Battle of Adrianople in 378, in which Emperor Valens and most of the Roman army in the east perished. It was not until Theodosius I signed a treaty in 382 that granted them extensive rights. After the death of Emperor Theodosius in 395, the Goth Alaric I and his army plundered the Roman provinces; In 410 he even conquered Rome. In the year 418 the Terwingen, which had finally formed into the Visigoths, were settled in Aquitaine , where they founded the Visigoth Empire . They extended their sphere of influence to the Iberian Peninsula and shifted the focus there in the early 6th century. In the early 8th century, the Visigoth Empire was destroyed by the invasion of the Moors .

The Lombards