Viking age

| Chronicle (small selection) | |

| 793 | Viking raid on Lindisfarne Monastery |

| 795 | Raids on Ireland begin (Inishmurray) |

| 799 | The raids on the Frankish Empire begin |

| 830 | renewed Viking raids on England |

| 840 | first Viking winter camp in Franconia |

| 841 | Establishment of Dublin |

| 844 | Viking raids in Spain and Portugal |

| 845 | Viking raid on Hamburg and the Seine valley, Paris pays 7,000 pounds of silver Danegeld to be spared |

| 856/57 | Sack of Paris |

| 866 | The great army of the Vikings lands in East Anglia |

| 880 | Harald Fairhair founds the Orkney Earltum |

| 881 | Vikings devastate the Carolingian heartland . Numerous cities are looted. Charlemagne's palace in Aachen is burned down. |

| 882 | The Vikings pillage Cologne , Bonn , Andernach , Trier and the Prüm Abbey . |

| 892 | After the lost battle near Leuven (Belgium), the defeated Vikings attacked the Moselle valley and again pillaged Trier and the Prüm monastery |

| around 900 | Discovery of Greenland by Gunnbjörn Úlfsson |

| 911 | Establishment of Normandy by Rollo |

| 914 | Loire Normans conquer Brittany |

| 980 | renewed attacks on England |

| 983 | Erik the Red settled Greenland |

| 1016 | Conquest of England by the Danes, Canute the Great establishes his North Sea empire |

| 1066 | End of the Viking Age ( Battle of Stamford Bridge , Destruction of Haithabu by the Wends ) |

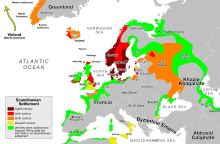

Viking Age is a term used in historical science . It is applied to Northern Europe, insofar as it was populated by the Vikings , and to Central, Southern and Western Europe, insofar as they were affected by their attacks.

The term "Viking Age" was coined by the Danish archaeologist Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae (1821–1885). The definition is essentially determined by the history of the event and is therefore to some extent arbitrary. The Viking Age in the Scandinavian region is determined differently by different researchers today. The war campaign of the Dane Chlochilaicus between 516 and 522 AD is mentioned as the earliest point in time . Although there are already 742 the attack on the Pictish Burghead Fort and 787 on Portland in Dorset had been in southern England, usually just the raid on is Lindisfarne 793 seen as the beginning of the Viking Age. The end is traditionally dated to 1066 (at the same time the end of the Early Middle Ages in England and the destruction of Haithabu ), although the predatory individual actions of smaller Viking groups had declined earlier. The Viking Age came to an end with the subsidence of the Viking trains. Sven Estridsson's reputation (1020-1074) began as a Viking on raids. Bishop Adam von Bremen later praised him for his education. The rough date commonly used today is 800–1050 AD, although the Viking ship graves at Salme show that as early as 750 AD, 50 years earlier, North Germanic warriors were killed in hostilities in the Baltic States .

The Viking Age was shaped by a large network of friendships. This included, on the one hand, personal connections with mutual obligations based on the ritual exchange of gifts, the bond of the individual to the clan and ancestors and, on the other hand, the confrontation with Christianity . This confrontation was prepared by the gradual change from smaller rulers to stronger central powers. The progress in shipbuilding and the associated mobility, both in war and in trade, led to wealth and cultural prosperity.

In the case of military campaigns, a distinction should be made between those that were led on a private initiative for personal gain and those that had a political goal and were therefore led by rulers or their competitors. What they have in common is that the war was financed by looting and spoils of war . These wars by no means stopped in 1066. Magnus Berrføtt fought between 1098 and 1103 wars against the Orkneys , the Isle of Man and Ireland , in which looting financed the war and, if possible, produced a surplus. Sweyn Asleifsson , a character from the Orkneyinga saga , died in 1171 during a Viking campaign against Dublin . The last time there was talk of Vikings was when the Birkebeiners moved to Scotland as Vikings in 1209 . But it was only a matter of sole proprietorship that no longer dominated the social lifestyle.

In Scandinavian historiography, the Viking Age is followed by the “ Christian Middle Ages ”. It is preceded by the Vendelzeit in Sweden and the “ Germanic Iron Age ” in Denmark . Those authors who, in addition to the warlike existence, also assign trade and handicrafts to the Viking concept, see less narrow limits and relocate the beginnings to the first half of the 8th century and the end to the period after 1100. Others reject this: This would obscure the defining characteristic of contemporary perception, which in the Viking concept has been preserved to the present day; the term loses its usefulness. The Viking Age essentially ran parallel to the Carolingian and Ottonian times of continental Europe .

Some authors also apply the term Viking Age to the history of the Rus . This is due to the fact that many cultural developments in the Viking Age took place primarily in the Baltic Sea region .

The sources

The source situation poses a problem for the description of the Viking Age. While a treatment of the Viking Age claims to describe the conditions of this time in all of Scandinavia, the sources are spatially very unevenly distributed. The conditions in Iceland and Norway are quite well documented, while there is hardly any productive news from Denmark and Sweden from this period. It is therefore inadmissible to consider the statements of the sources from one area to be representative of Scandinavia. This applies in particular to customs and the position of women. The social conditions in Denmark and Sweden may have been different from those in Norway or Iceland.

Another problem is the modern criticism of sources, which calls into question the credibility of the sources. This leads to a certain arbitrariness of the representation. It is assumed here that the narrative sources embedded their action, whether it be historical or not, in real life circumstances. However, it must be checked whether it is the living conditions at the time of the events described or at the time of the author. Figures from the time, of which the authors could only have oral records, deserve particular skepticism. This applies, for example, to the strength of the fleet at the Battle of Hjørungavåg 986, which is probably exaggerated. Contemporary Frankish annals have also often exaggerated the number of ships, as shown in the relevant section of the Vikings article . Nevertheless, the basic structure of the course of the battle can be considered plausible.

The people

The graves show that the average age at death for men was 41 years and that of women was 51 years. The skeletons are evidence of hard physical work. There are clear traces of osteoarthritis - especially in women. The female skeletons show an average height of about 161 cm, that of the male skeletons of about 174 cm (the averages vary from region to region). There were also people up to 185 cm tall. Judging by the grave goods , the taller people apparently come from the higher social classes.

The Scandinavians in England and Ireland lived almost exclusively in closed territories or localities. Individual farmsteads are unknown. The situation is different in Scotland and the islands ( Hebrides , Orkneys, Shetlands and the Isle of Man ), where many individual farms have been found. In the dwellings, the floor was made of tamped clay, which was strewn with straw.

Apparently they had sniffer dogs for the hunt.

Diseases

In the Rígsþula it says drastically:

|

Hann nam at vaxa |

It began to grow |

In Kristianstad in Skåne , a cemetery with 128 individuals was explored. The burial ground is dated to the late Viking Age. Of the 128 deaths, 79 had died in the first year of life. Only 10% were 60 years of age or older. Most children and at least a fifth of adults were iron deficient . Many had very bad teeth. Those over 60 usually had only a third of their teeth. Broken arms and legs as well as dislocated arms were found in many skeletons. There were also joint and skeletal diseases. Osteoarthritis was the most common disease. This is especially true for the knee joints of older women. Those buried on the outside of the cemetery apparently had leprosy . These statements do not correspond to the image of the courageous and enterprising Vikings. In particular, the oldest Christian burial site that has been explored in Lund shows that leprosy was a widespread disease. A case of tuberculosis was also identified.

Archeology has found numerous diseases in skeletons and excrement:

- Diseases of the bones and joints

- rickets

- osteoporosis

- Osteomyelitis (inflammation of the bone marrow)

- Tibial periostitis (inflammation of the periosteum on the shinbone)

- Spina bifida occulta (invisible open back): 10–15%

- Paget's disease

- Hyperostotica spondylosis ( Forestier's disease )

- Spinal tuberculosis

- arthrosis

- gout

- other illnesses

- Dental disease

- Lumps

- cancer

- leprosy

- multiple sclerosis

- Heart disease (derived from the combination of genetic abnormalities that cause heart disease)

- Anemia ( anemia )

- Sinus inflammation

- Dupuytren's disease (connective tissue disease on the palm of the hand)

- Whipworm ( Trichuris trichiura )

- Roundworms ( Ascaris )

The hygienic conditions were poor in built-up areas. The distance between the drinking water well and the faecal pits was often not great. The archaeological findings in York show that the process water was not sufficiently separated from the wastewater. Ibn Fadlan reports that the Rus on the Volga have poor hygiene standards. However, statements made by sources or findings from a specific region cannot be generalized.

Clothing and personal hygiene

The costumes seem to have varied widely. In addition to the traditional women's clothing, which was held together with bronze buckles and clasps on the shoulder, especially in the graves in today's Denmark and in the western part of Skåne (southern Sweden), Western European clothing fashions without metal clasps , but with fabrics in the silver or gold threads were woven in, as they are known from Frankish and Byzantine fabrics. Different types of pearl necklaces were worn. Bronze bangles were unknown in the West, but common in Austria .

In general, after the representations and the care utensils in the graves, one was very well cared for. Ibrahim ibn Jaqub reported from his trip to Haithabu around 965 that men and women had used eyeshadow. An English writer reported that the Northmen bathed, groomed their hair and were well dressed on Saturday for success with the English ladies. The neck was shaved and the hair on the forehead long. This certainly did not apply to the landless and servants .

food

The Viking Age men were on average 173 cm tall, which suggests good nutrition. The people of the Iron Age and the Viking Age ate meat from beef, pork, sheep, chicken and fish. The meat was preserved by curing, drying or smoking. Cheese, butter, buttermilk and sour milk were made from milk. Eggs were obtained from chickens and wild birds. In the Iron Age, oats and barley were grown. In the Viking Age, rye, which had been imported from Slavic regions, was added. Vegetables were peas, beans, cabbage, onions and cress. Apples, plums, blackberries, raspberries, wild strawberries, sloes, elderberries and hazelnuts were collected in the forest and in the fields. Salt was essential. It was obtained from seawater or imported. Honey was used as a sweetener. One drank water or milk drinks and fruit and berry juice. Beer was brewed from barley and flavored with hops or porst . Mead was made from honey, water and aromatic herbs. Bjórr was probably heavily fermented cider. Grape wine was imported.

Grain was used to cook grits or it was ground in a hand mill and bread was baked from it. Sourdough served as a leavening agent. The flour had a lot of impurities due to the wear and tear of the hand mills, which wore the teeth. Flat cakes were baked on pans over an open fire or in ovens. Fruit and berries were eaten raw or cooked as groats. Vegetables could be made into soup. People cooked or roasted in pots or on a spit over an open fire. Meat was also cooked in pits. Hot stones are put into the pit, the meat is wrapped in leaves, over it again a layer of hot stones and the whole thing covered with sod - in Iceland this is called hólusteik. It took 1 hour per kilo of meat.

Attitude to life

As in all times, the attitude to life may not have been uniform. In addition to the view that life was predetermined and that magical powers also acted on it, there were also people who were non-religious and this-side-emphasizing realists, averse to any supernatural. Almost only the sagas are available as sources ; these statements only apply to Norway and Iceland.

The sources mainly reproduce the first group, since in the sagas the predestination in the narrative style increases the tension. In this group, the connection between the individual and the ancestors also played a special role. These or their followers also looked after their living offspring, for example through warning dream images. Groa, a sorceress in the Vatnsdœla saga, wanted to win Thorstein over with magic and invited many, including him, to a banquet.

"Og hina þriðju nótt áður Þorsteinn skyldi heiman ríða dreymdi hann að kona sú er fylgt hafði þeim frændum kom að honum og bað hann hvergi fara. Hann kvaðst heitið hafa. Hún mælti: 'Það líst mér óvarlegra og þú munt og illt af hljóta.' Og svo fór þrjár nætur að hún kom and ávítaði hann and kvað honum eigi hlýða mundu and tók á augum hans. Það var siðvenja þeirra þegar Þorsteinn skyldi nokkur heiman fara að allir komu þann dag til Hofs er ríða skyldu. Komu þeir Jökull og Þórir, Már og þeir menn aðrir er fara skyldu. Þorsteinn bað þá heim fara. Hann kvaðst vera sjúkur. Þeir gera svo. Þann aftan þá er sól var undir gengin sá sauðamaður Gró að hún gekk út og gekk andsælis um hús sín og mælti: 'Erfitt mun verða að standa í mót giftu Ingimundarsona.' Hún horfði upp í fjallið og veifði giska eða dúki þeim er hún hafði knýtt í gull mikið er hún átti og mælti: 'Fari nú hvað sem búið er.' Síðan gekk hún inn og lauk aftur hurðu. Þá hljóp aurskriða á bæinn og dóu allir menn. Og er þetta spurðist þá ráku þeir bræður á burt Þóreyju systur hennar úr sveit. Þar þótti rhymes jafnan síðan er byggð Gró hafði verið og vildu menn þar eigi búa frá því upp. "

“Three nights before he was supposed to ride home, Thorstein dreamed that the woman who had accompanied his ancestors would come to him and ask him not to ride. 'That seems unwise to me, and it will bring you bad luck too.' And so it went for three nights that she came and reproached him and said it was not going to be good for him, and she touched his eyes. It was the custom of the Seetaler when Thorstein planned a ride that everyone who wanted to ride with him came to Tempel that day. They came, Jökul and Thorir, Mar and the other men who wanted to travel. Thorstein asked her to ride home, he was sick. They did it. That evening, when the sun had set, a shepherd Groa saw how she stepped out of the farm and strode around her farm against the course of the sun and said: 'It is difficult to withstand the happiness of the Ingimund sons.' She looked up at the mountains and swung a pouch or cloth in which she had knotted a lot of gold, her property, and said. 'What must come will come.' Then she went in and closed the door behind her. A rock fall fell on the farm and everyone was killed. "

In general, premonitions played a major role. They were evidently believed to be real by the writer and readers. Some of them are only a literary paraphrase of an assessment of all known factors from which the development of the event could be derived. Another trait is the often-described fatalism that persisted into Christian times. In the account of the Battle of Fimreite , for example, it is said that King Sverre had left his ship and rowed to his fleet to give it new orders. Then it means:

“The king rowed back to his ship. Then an arrow went into the stern of the boat over the king's head, and immediately afterwards another on the deck in front of the king's knees. The king sat quietly without making a fuss, and his companion said, 'One bad shot that, sir!' The king replied: 'It comes just as God wants it!' "

Social structures

Social stratification

The aristocracy, which can be identified after 1000, is archaeologically detectable through large courtyards that comprised many buildings. Their basis of legitimation lay in their wealth and the subsequent generosity towards their entourage. Such large farms have been researched in Uppåkra (now in the municipality of Staffanstorp ) a few kilometers southwest of Lund , in Tissø in western Själland , in Lejre near Roskilde and in Borg in Lofoten . According to the finds (scales and weights as well as Arabic coins) most of the wealth came from trade. The retinue of the aristocrats was a troop of warriors called hirð . The king had the largest troop, and there is some evidence that this core troop in Canute the Great is identical to the Thingslið in England, which is often mentioned in its context . The earliest mention is on a rune stone from Uppland from the period between 1020 and 1060. This warrior troop exercised something like police power in the Lord's sphere of influence and served to enforce their own claims in local disputes; because otherwise there was no state monopoly on the use of force .

The graves also show a clear stratification of society in their grave goods: leading personalities, a broad middle class who, depending on their wealth, had more or less valuable grave objects, and slaves without grave objects.

At that time, in some quarters, it was right for a man to go abroad, gain wealth either through robbery or trade, and first return home rich and covered in glory to take up the traditional way of life there. The heimskr maðr , who stayed at home, was synonymous with "fool". But that doesn't mean that every young man in the upper class went on a Viking trip. They are only the main characters in the relevant reports.

The main dividing line within society was the line between the free and the unfree. Within the group of the free there were differences determined by property and family. The only quality that really embraced all free people was male holiness . It was reflected in the man's penalties payable for manslaughter, bodily harm, or honor, to him or, if he was killed, to his family. Such a penance was not entitled to the unfree, at most compensation to the Lord. In the case of the free woman, there was also penance for sexual assault.

After the introduction of kingship by Harald Hårfagre in Norway, a class society emerged that consisted of king, chiefs, peasants and slaves and was regarded as god-given.

The king

Like other kings, a king derived his legitimation from his descent from gods. With Harald Hårfage it was the descent from the Ynglings who traced back to the god Freyr , as Tjodolf von Hvin shows in the Ynglingatal , with the Ladejarlen it was Odin, as Eyvindr Skáldaspillir in Háleigjatal explains. Since he came from a divine race, the well-being of the people and general happiness were tied to him. His advance in battle was meant to show that the gods were with him. A gift from the king was not only of material value, but also granted a share in the salvation of the king. It is assumed that originally all chiefs attributed their gender to gods. With the increasing concentration of power in Norway on two families, the Hårfagreætt and the Ladejarle, the others have been "desacralized". The final introduction of Christianity after multiple failures led to a fundamental change in legitimation. The descent from a pagan god could not be sustained. The new basis was created by the sacralization of Olav the Holy as a martyr, to whom all kings subsequently traced themselves back, even if the actual descent for many is more than doubtful.

The king exercised supremacy over all parts of the country, which cannot be precisely delimited, but whose content can only be vaguely determined. Charges, meals during visits and military successes in the war should represent the main content. He did not rule over an area, but over people. Torbjørn Hornklove calls him dróttin norðmanna (King of the Northmen). But he was also seen as the owner of the land. The stereotypical legal consequence of persistent violations of the law was the expulsion from the country, which was expressed, for example, in Gulathingslov:

“En ef hann vill þat eigi. þa scal hann fara or landeign konongs várs. "

"And if he doesn't want that, he should leave our king's property."

In return for the taxes, he was responsible for the external defense of his sphere of influence. See The inner development of Norway during the Viking Age .

The Norwegian king did not then have the power to govern as it did later. He had neither the legislation nor the jurisdiction and was essentially dependent on the local authorities. The army followed only partially. This becomes clear in the dispute between King Olav and Canute the Great in autumn 1027. At a deliberative meeting ( húsþing - Hausthing) the king encouraged the Swedish allies and their king Önund to stay on the ships in autumn and wait for the warriors Knuts had withdrawn home and pulled against his weakened fleet. Not the king, but the leaders present replied:

„Þá tóku Svíar aðtala, segja að það var ekki ráð að bíða þar vetrar og frera‚ Þótt Norðmenn eggi þess. Vita þeir ógerla hver íslög kunna hér að verða og frýs haf allt oftlega á vetrum. Viljum vér fara heim og vera hér ekki lengur. ' Gerðu þá Svíar kurr mikinn and mælti hver í orðastað annars. Var það afráðið að Önundur konungur fer þá í brott með allt sitt lið [...] "

“They said it was not advisable to wait for winter and frost, even if the Norwegians tell them to. 'You just don't know how the ice can lie here and how the sea so often freezes over completely in winter. We want to go home and not lie here any longer. ' The Swedes grumbled loudly and they all spoke to one another in the same vein. It was finally decided that King Önund should go home with his whole army. "

In Norway there was initially a hereditary kingship, which entitles all sons to the same kingship, after the end of the civil war a restricted electoral kingship. But even under the hereditary kingship, the king required acclamation by a thing in which only men from a royal family were eligible. At the acclamation of Olav the Holy (995-1030) as king, he promised "the preservation of their old national laws and protection against foreign armies and masters". In return he was entitled to hospitality wherever he went with his men.

The king had his own crew around him, which was later called hirð . He had to be a role model in the struggle and in the way of life if he wanted to be recognized. It was less about his title, which he wore because he belonged to a powerful gender, than about the motivation he was able to instill in his team. So was Erik Bloodaxe not fast enough to draw up a fleet against his rival Håkon the Good, "because some of the nobles left him and went to Håkon". Erik's sons also had to leave Norway with their mother Gunnhild when Jarl Håkon came to Norway. "They called an army together, but only a few people followed them." The best examples of early ideals are given by the skald poems, which are cited in the Heimskringla, as they are the oldest evidence, often written immediately after the events described and passed on further.

|

Úti vill jól drekka |

Outside Jul will drink |

Over time, the kingship grew stronger. Foreign role models and influences were decisive. Not only did Harald hårfagri send his son Hákon to England to the court of Aðalstein and he grew up there, the future kings also later gained their experience abroad, so that Snorri puts the sentence in the mouth of Olav's father, the saint of Olav : " Now you have also proven yourself in battles and have formed yourself on the model of foreign rulers. "

Chiefs

In the Viking Age there were around 20 large and dozen small chiefs. If one assumes that around 800 there were around 100,000 people living in Norway, it follows that the areas of sovereignty must have been very small as a rule during this period. The power of the chiefs rested on their network, which consisted of more or less dependent peasants. These had to support the chief in his undertakings, and the chief had to give them protection and ensure their livelihood. The relationship can be described as the relationship between patron and client . Then there was the Hirð, a group of professional warriors around the chief. Both presupposed a solid economic basis, which had to be created through warlike undertakings. This meant constant expansion of the areas of power through victories over other chiefs. Therefore, society was unstable in the pre-royal period. Then there were the conflicts that arose from inheritance law. Because all sons born in and out of wedlock had equal rights in the succession. Since they originally traced their sex back to gods, chiefs also had priestly functions. In Iceland they were called "Goden".

farmers

The peasants were at the core of Norwegian society from pre-royal times to the 19th century. They ran a farm and had clear duties: to protect the people living on the farm and to take part in the meeting of things. There were great economic differences among the farmers. Some owned large estates, some of which they leased out or had slaves run. Unlike the slaves, all peasants had "honor". At the top were the so-called "Haulde", a peasant aristocracy. In the Østlandet the term still had the original meaning of the land-owning farmer, in the Vestlandet Frostathingslov and Gulathingslov show that they were Odal farmers . To achieve Odal status, a family between four and six generations had to live on the same property. In Landslov the time was reduced to 60 years. It is not known how large the proportion of these farmers was. In the warrior society, honor was the highest good, and so, in order to increase honor, there were often armed conflicts. These honor battles could only be fought between people of the same status. They served the social differentiation within the same group. It was unthinkable that a chief would challenge a peasant, for no honor could be gained by challenging a member of a lower social class.

The individual farm with its associated land and the outskirts (Inn- and Utmark) was the basic economic unit on which the entire society was built. This is also reflected in contemporary mythology: in Asgard each god had his own hall. In Midgard the people had their farms and in Utgard the trolls and evil forces sat. Innmark and Utmark have been models in this worldview. The individual farms produced their own needs as much as possible. But the different resources required a certain specialization: fishing and iron extraction could be used to exchange for other important goods.

There were also small settlements. They were both a social unit and a production community. The settlement owned fields. Every farmer had his fields in the different districts without boundary walls opposite the neighbor. The farmers plowed, sown and harvested together. In addition, there were meadows and forests as commons . The whole thing belonged to one or more landlords.

warrior

At the beginning of the Viking Age, the warriors were recruited from the peasants. Warrior later also became a profession. A stone from Uppland on which a warrior is praised that he was the best farmer in Håkon's entourage proves that the peasants also performed military service in the late period :

"Gunni ok Kári reistu stein eptir [...] Hann var bónda beztr í róði Hákonar."

"Gunni and Kári put the stone afterwards [...] He was the best farmer in Håkon's squad."

róð is described in the Upplands Law as follows: “And now the king offers the allegiance and the peasant army, he demands the rowing and warrior team and the equipment.” There was already a standing warrior troop.

slaves

In addition to these described groups of people, there were servants / slaves. They had no affiliation with families. They had no rights. Their origins played no role in society. They were owned by the Lord. There is news about them in the later Old Norwegian and early Swedish laws. But these allow certain conclusions to be drawn about the previous conditions. The economic importance of the slaves at that time is one of the unanswered questions in Norwegian historical research. English and Irish sources report on kidnapping. For example, in the year 871 it is reported that Scandinavians from Dublin enslaved large numbers of English men and Picts . But it does not appear from this that a large number of them came to Norway, as many may have been sold abroad. Also, there is no clue as to what number it was. Archaeologically, the facts are barely comprehensible. Often the prisoners were not sold, but were released for a ransom. If the ransom was not paid, the Vikings would often kill them. Jarl Erling Skjalgsson is reported to have had 30 servants around him at all times. They were allowed to do business for themselves and could buy their way out within two to three years. With the transfer fee, the Jarl bought new servants. Christian influence can already be felt here. Régis Boyer thinks that the slavery of the Viking Age in Scandinavia is not comparable to the slavery in ancient Rome . He thinks that the ideals of the Vikings opposed such an inhumane attitude. However, these ideals oppose a literary environment that is already contaminated by Christianity and which is also influenced by continental ideals. For pre-Christian society, an ideal relating to the species “human” is not tangible. Rather, all the ethical norms to be determined were limited directly to clan and allegiance. In Sweden slaves are documented in numerous wills until the 14th century, in which wealthy testators gave their slaves freedom. Not only did they come from raids, but many also voluntarily became slaves in order to ensure their supplies. There was also enslavement as a punishment. The content of slave status varied from landscape to landscape and from epoch to epoch. But one thing was consistently characteristic: the slave lacked male holiness. He had no rights to his owner and his family, who could use force against him or sell him with impunity. The violation of the slave by a third party was viewed as damage to the master’s property. A slave's children, like those with pets, belonged to the owner. However, the regulations were also different here: According to the law in Skåne and according to the Västgötalag, the child of a slave woman was a slave. In Östgötalag the child of a free man was free with a slave girl. In Svealand, a child of such a mixed marriage always followed the “better half”. There the possibility of such a mixed marriage was also regulated by law. This development is attributed to the influence of the church.

The lawlessness also meant that he could not appear on a thing. He was also not legally competent. He was also unable to obtain his own release. He did not gain full freedom after a release until he was adopted into a free sex by a member of a family. In Uppland and Södermanland the slave had a man's holiness limited to persons outside the family of the owner. The sale of the slave was also prohibited there.

There was a semi-free class ( fostrar or frälsgivar ). These were probably slaves who had been given a small piece of land for their own cultivation for life. The owner was relieved of maintenance, but the slave retained his status without rights. However, the damages to be paid to the owner in the event of injury were higher, and they could also marry a free one, and the children from the marriage were free members of the maternal family. The regulation of this semi-free class belong to the youngest layer of tradition.

In the Skarastadgan of 1335, King Magnus Eriksson ordered that from now on all children of Christian parents should be free. This development is traced back to the church, which - without shaking the social system - saw slaves as having equal rights in the church from the beginning. For the large landowners with widely scattered estates, it was economically better to let legally independent servants and farm laborers manage their estates than to have slaves who had to be monitored and maintained. The previous slaves were released en masse in the 14th century. The fate of these farm workers, however, was no different from that of the slaves. The large farmer retained the legal right to corporal punishment, and the poor farm worker had to submit to the working conditions if he did not want to be punished as a tramp. Since the landlord had now got rid of responsibility for the former slave, the latter now bore the risk of unemployment and hardship in old age. The right to corporal punishment was limited to underage servants in 1858 and only abolished in 1920.

Special functionaries

Very little is known about special functionaries in pre-Christian society.

- One of the functionaries was certainly the “priest”, who for etymological reasons is assigned the name Gode . In Norway this function was performed by the chiefs. In Iceland they were called Goden. There were domestic, regional and national sacrificial festivals. (see article North Germanic Religion and Yule Festival ). Steinsland assumes that the religious rituals on the individual farms were led by women and that only the regional and national festivals were reserved for male leaders.

- Initially, a god also presided over the thing assembly. According to Icelandic sources, he wore a sacred gold bracelet on his upper arm. The oaths were placed on this bracelet. A law spokesman also appeared at the thing, who had to recite the laws by heart.

- Other officials were trained at the royal court, in the army and in the fleet. As a rule, they were recruited from the peasant aristocracy.

The family association

The society of the Norwegian Nordmanns was essentially shaped by external, especially Franconian influences. At the same time as the expansion of their sphere of influence outwards, internal colonization began. Only when the conditions no longer allowed further expansion in the interior did the emphasis shift to the expansion abroad, which is associated with the Vikings. Archaeologically, one can ascertain a steady increase in the built-up area since the turn of the ages with a temporary slump in the 6th century. The new district names before the Viking Age, which all begin with a personal name, allow the conclusion that agriculture was carried out by individual small families during this time. Nonetheless, before the Viking Age, society was shaped by family associations, as there was no higher authority above the extended family. In the Viking Age, however, the greater mobility led to a reorientation, as when abroad the own extended family could only provide limited and very limited support in cases of conflict. Here the group to which a person belonged came to the fore.

Nonetheless, the term “family group” to which a person belonged is important at this time. For a gender to stick together in all things, there must have been a common group feeling for all members. That is only possible in a strong patriarchy or matriarchy. In the Viking Age, due to the patrilinear form of personal connections, a patriarchy can be assumed, where the eldest of the family determined sons, wives, unmarried daughters and daughters-in-law. But this was different before. If a woman married before the Viking Age, she remained a member of her own family unit, and the maternal family unit was as important to the children as the paternal one. This included that, for example, two nuclear families of two brothers never had the same view of their closest relatives, except for the rare case that two brothers were married to two sisters. This society did not consist of separate sexes side by side, but of small families as nodes in a large network with connections criss-crossing the area and resulted in an asymmetrical pattern. It is therefore not surprising to hear of an argument between groups that were related to each other. The term “trunk” is avoided here because it encompasses too many different phenomena to be used meaningfully in this context.

Friendship

The institution of friendship was at least as important. These are political alliances of mutual support before the final assertion of royal power. It is therefore most evident and effective in the Icelandic Free State Period. In contrast to the family association, into which one was born and in which nothing could be changed, the friendship association was a social construct that could be aligned to the respective political conditions. In this way, social networks were formed to expand and secure power. Such friendships were therefore only formed in or with the upper class. One learns nothing of friendships between the farmers. They were grouped into regional districts ( hreppar ), within which the duty of mutual assistance was already given. On the other hand, friendships were made between farmers and chiefs (Goden). They were connected with mutual duties of loyalty and support and, on the part of the god, with the duty of protection. Friendships were established through mutual gifts, which also included the fact that the farmer left one of his daughters to Goden as a concubine, who thus got a better position than if he had married her to another farmer. At the beginning of the settlement period there were considerably more Goden than at the end of the Free State, and it happened that farmers made friends with two Goden ( beggja vinir ). As a result, the social networks overlapped, and these farmers were the right mediators in the conflict between their gods. As the number of Goden decreased, such double loyalties occurred less often, which, in the absence of suitable intermediaries, led to the bloody disputes of the Sturlung period .

The dependence of friendship on the gift in Norway practically led to the merchantability of the federal cooperative. Canute the Great made Olav Haraldsson (the saint) alienated by sending them great gifts through envoys. On the one hand, royal power and chief power were in competition with one another, on the other hand, they were dependent on each other. In the civil war in particular , loyalty relationships frequently changed, depending on where the chiefs saw their greatest advantage in expanding their position of power. That only changed when the king derived his legitimacy from God in the late Middle Ages. This also changed the function of the gift from establishing a friendship with an obligation of loyalty, which was already given due to the king's position as God's representative, to bribery. This can be seen in the development of the law:

"Þat er upphaf laga narra at ver scolom luta austr ac biðia til hins helga Crist ars og friðar. oc þess at vér halldem lande varo bygðu. oc lánar drotne varom sanctuary. se hann vinr varr. en ver hans. en gud se allra vorra vinr. "

“It is the first in our law that we bow to the east and pray to the Holy Christian for prosperity and peace and that we can continue to inhabit our land and the salvation of our Lord. He should be our friend and we should be his friends and God should be the friend of us all. "

This paragraph was deleted in the Landslov of 1274. The king no longer had to rely on the friendship of the peasants to ensure loyalty.

After Christianization, friendships with saints and with God were established according to similar rules. Churches and land were donated to them and support in conflicts was expected from them. The saints were called Gudsvinir (friends of God). Bishop Guðmundur Arason asked, when he saw his wife die, to convey his greetings to a number of saints, including Mary, the Archangel Michael and Olav the saint, but especially his friend ( vini mínum ) Ambrosius. In the 13th century, however, the relationship to God changed. The helping God, with whom one could negotiate with gifts, became a punishing God who strictly monitored the observance of his commandments regardless of rank and gifts.

Women

General

Politically, women were not equal to men. So they were n't allowed to participate in the thing . But they were not socially disadvantaged.

The most richly equipped known grave of the Nordic Viking Age is assigned to a woman: The dendrochronological ordinance dates from around 820 AD. Two distinguished women - possibly a queen with a young companion - were buried in the burial mound of Oseberg . The wealth and power of the dead can be read from several clues. On the one hand, it is a very large burial mound, on the other hand, the dead were given numerous valuable grave objects such as sleds, animals, ships, boats, wagons and food. The co-burial of a companion is also known from other Scandinavian graves from the 1st millennium. Other burials also show higher-ranking female personalities. For example, a chamber grave was documented on the Viking Age grave field of Kosel near Haithabu , in which a woman was laid in a car body. Two horses with bridles lay at her feet: a complete carriage team that had probably served the deceased during her lifetime and on the last trip to the grave.

Economic position

There were clearly defined areas of responsibility for women and men, which were later even stipulated by law. Grave goods and literary evidence serve as sources for this. The Grágás , the medieval Icelandic code of law, represented the area “this side of the threshold”, i.e. in the house, as the territory of the woman, while the man “had to take care of what was to be done outside”. The social fabric was heavily dependent on women: They administered and ran the farm during the absence of their husbands and sons, some of which lasted for years. Courtyards were often named after the owners z. B. Hårstad to Hårek and Ingvaldstad to Ingvald. The fact that farms are also named after women, e.g. B. Møystad east of Vang , old Norwegian "Meyarstaðir", also after a young unmarried woman, to which the syllable "Mey = girl" indicates, shows that women could also take up leading positions. The fact that this is an isolated case shows that normally women were not treated as equal to men as a group, but in exceptional cases they were able to assert themselves on an equal footing with men. There are a total of 20-25 farms that are named after women, usually with their names and not anonymously. In Iceland, around 10% of farms are named after women. For women, to whom either rune stones were dedicated, or who themselves dedicated rune stones to other women or men, the ratio is different: There are 20% of women or for women. This difference is also due to the fact that the establishment of a farm required enormous physical effort, so that only a few farms have been named after the founders. Later, women were able to own farms through inheritance or other events and thus rise to become people to whom rune stones were dedicated or who commissioned them themselves. With a rune stone with the inscription: "Rannveig erected this stone after Ogmund, her husband." the widow documented that she now ran the farm herself.

The preparation of food was part of the women's job. The manufacture of textiles was reserved for women. This also included weaving the huge ship sails. It is indicative of the role played by women in Rus that 20% of the scales and weights, which are typical grave goods from traders, were found in women's graves: apparently women played an essential role in trade. Nevertheless, it cannot be overlooked that far fewer women graves with grave goods have survived than men graves. From this it can be concluded that men could have a lower status than women and still receive an impressive grave.

Legal Status

The runestone from Hillersjö in Uppland from the 11th century is a source for the fact that women could also play an important role in the line of succession. Widows had the most privileged position in this society. A widow could inherit her son if he died without an heir of his own. After her death, the inheritance went to her relatives. If necessary, women could also take over functions from men, for example, as an unmarried woman, founding and running a farm. The social norms did not prevent them from doing so.

Position in marriage

Women on Viking trains are not reported until the middle of the 9th century, when the first Scandinavians began to winter in France. However, it was mainly women who were taken as booty in the raids.

The expression " purchase of the bride " poses a certain problem . One can hardly doubt that this term, which occurs in many Nordic laws, originally reflects a real purchase. In the 11th century the term had long since received a weakened meaning. But nevertheless a sum of money was still paid for the bride - mundr . Originally, the bride price was paid to the bride's father, but in later laws this money became the bride's property. The expression in the sagas is clear: The suitor's friend says to the bride's father: "My friend wants to marry your daughter. There should be no lack of assets!" The minimum price after the Gulathingslov was 1½ marks. That was called the "poor mouth". The father was free to ask the daughter about it. If he found the trade advantageous, he took it immediately. But with the daughter's consent it was easier and the risk of complications later was lower. Whenever possible, she tried to marry a man of a higher rank than herself.

Both spouses had the same right to divorce. Her family was obliged to take her in afterwards. Also, the woman had to have a good reason if she didn't want to lose her dowry. The divorced, like the widow, was now much more free to choose her next husband. But here too she had to seek advice from her relatives if she wanted to ensure her full rights.

The requirement of virginity at the first wedding was absolute for the bride, as was the requirement of fidelity during marriage. The family's honor depended on it. Icelandic law was the strictest there: the man had to pay a fine of 3 marks for a secret kiss. Kissing a girl against his will resulted in expulsion. Writing love poems to a girl was strictly forbidden, but it was still practiced. It happened that the father refused to consent to marriage if the bride and groom had already agreed. The women had no claim to the inheritance from their parents, but only to a dowry in keeping with their class, consisting of trousseau and valuables. However, if the girl was still unmarried when her father died, she was entitled to a share corresponding to her assets. The husband could only manage the dowry. She was kept separate from his property. The legal capacity was limited in amount. The woman could only do business effectively up to a certain amount.

Women as warriors?

In a study from 2017, the opinion was expressed that new DNA analyzes had shown that in chamber grave 581 von Birka, which was opened in 1878, not a man but a high-ranking warrior was buried. Criticism was raised by Judith Jesch, professor of Viking Studies at Nottingham University, who complained about methodological shortcomings. An Irish text from the early 10th century tells of Inghen Ruaidh ("Red Girl"), a female warrior who led a Viking fleet to Ireland. Through this narrative, the shield maids also appear in a new light in the Völsunga saga.

Women in literature

While the scald poetry was generally a purely male-oriented literary genre, Sigvat Tordsson did not shy away from breaking new ground here and making a woman the subject of a poem of praise. He wrote a prize poem for King Olav II Haraldsson's wife, Queen Astrid Olofsdottir, of which three stanzas have survived. In it he portrays Astrid as a “good advisor” and “eloquently arguing, wise woman”. The Valkyries are often mentioned in the literature of the time . They were a kind of female war demons: they chose the warriors who would die on the battlefield and be brought to Valhalla to become warriors of Odin .

In all Icelandic sagas, men are formally the main characters and bearers of the external course of action. But women also play a big role in some sagas. You can influence what happens as an object of male desire. Women can incite men to do what they want. Basically, the same character traits are valued in women as in men. A saga woman who corresponded to the male ideals with revenge and honor as central concepts was considered a strong woman. In some sagas one also encounters softer types of women. This image of women is influenced by the romantic ideal of women in the translated courtly poetry. Women as secondary characters soon lose their individual traits and become stereotypes. In the sagas, women are measured by the standards of men. The man is judged on his character traits. A woman is judged according to the extent to which she uses her strength to support the men, or to act against them, who should support them according to social norms.

Sorcerers and sorceresses

Before and during Christianization there were people who practiced magical practices. The men were called Seiðmenn , the women were called Völva or Spákona (seer). The women were old and unmarried or widowed, which ensured them great social independence. They enjoyed a very high reputation, as is described in the saga of Erich the Red (the passage is reproduced in Völva). As a rule, the Seiðmenn were not respected. Insofar as they used magical practices in combat, as described in the sagas every now and then, this was considered unmanly and not worthy of a real warrior. They also seem to have been considered homosexual (see Magic for details ). The spell usually referred to causing severe thunderstorms or making clothing that no sword could pierce. How the practices were carried out is almost never described. One of the very rare descriptions concerns the attempt of a woman who knows magic to protect her failing son from persecution by trying to make his opponents go mad.

"Og er þeir bræður komu að mælti Högni: 'Hvað fjanda fer hér að oss er eg veit eigi hvað er?' Þorsteinn svarar: 'Þar fer Ljót kerling og hefir breytilega um búist.' Hún hafði rekið fötin fram yfir Höfuð sér og fór öfug and rétti Höfuðið aftur milli fótanna. Ófagurleger var hennar augnabragð hversu hún gat þeim tröllslega skotið. Þorsteinn mælti til Jökuls: 'Dreptu nú Hrolleif, þess hefir þú lengi fús verið.' Jökull svarar: 'Þess er eg nú albúinn.' Hjó hann þá af honum Höfuðið og bað hann aldrei þrífast. 'Já, já,' sagði Ljót, 'nú lagði allnær að eg mundi vel geta hefnt Hrolleifs sonar míns og eruð þér Ingimundarsynir giftumenn miklir.' Þorsteinn svarar: 'Hvað er nú helst til marks um það?' Hún kvaðst hafa ætlað að snúa þar um landslagi öllu ‚en þér ærðust allir og yrðuð að gjalti eftir á vegum úti með villidırum og svo mundi og gengið hafa ef þér hefið enuyr.

“And when the brothers came over, Högni said: 'What kind of devil is coming up to us there? I do not know what it is.' Thorstein replied: 'Here comes Lyot, the old woman, and has done a strange job.' She had thrown her clothes over her head and was walking backwards and stretching her head back between her legs. The look in their eyes was grayish, as they knew how to shoot it like the trolls. Thorstein called to Jökul: 'Now kill Hrolleif. You burned for a long time.' Jökul replied, 'I'm ready for that,' and cut off his head and wished him the devil. 'Yes, yes,' said Lyot, 'now it was close to the fact that I could have avenged my son Hrolleif. But the Ingimund sons are great lucky men. ' Thorstein replied: 'Why do you mean that?' She said she wanted to overturn the whole country, 'and you would have gotten mad and stayed crazy out with the wild animals. And so it would have happened if you hadn't seen me sooner than I saw you. '"

The Sami (called "Finns" in the sagas) were a certain exception , as they were outside Scandinavian society. Above all, they were future-oriented. However, the line between compulsion and magic was fluid. A Finnish seer predicts the foster brothers Ingimund and Grim that they will leave Norway and move to Iceland. They take this as an order and say goodbye to the Norwegian king. He dismisses them with the words that it is difficult to act against magic words.

A focus of sorcery remained in northwest Iceland until modern times. They were men who vegetated on the lowest limit of the subsistence level and tried to improve their circumstances through all sorts of magical practices or at least to prevent further blows of fate. These were essentially amulet spells, i.e. magical symbols that were to be attached to doors or buried under thresholds, or that were carried with you.

Vikings

There were the Norwegian and Swedish Vikings of the aristocratic upper class, who at a certain early stage of life went on a predatory voyage into the distance and possibly even observed a certain code of honor that they took with them from home, for example that one made a robbery public and that one should did not steal away secretly. The Vikings who plagued the Frankish Empire and England were radically different from these social groups. It was a pure robbery with no particular ties to the homeland. While they apparently returned home after their raids at the beginning of the 9th century, this stopped in the course of the 9th century. The fact that they set up fortified camps in the area to be plundered, into which they retreated in case of danger or even wintered, is often confused with or associated with the later land seizure. Dominion over land was never the goal of the predatory northerners. Their cruelty and destructiveness, which were already unimaginable at the time, made them a social group that could no longer be integrated into the gradually growing centralization tendencies in their home countries. Their accumulation of silver and treasures had no function. What they needed they stole. There was no use for the treasures. An Irish source reports that the Viking fortress Dublin was conquered and that enormous treasures were found there.

Social rules

Relations between the sexes

Daily life was determined by a multitude of unwritten rules. This included in particular the distribution of roles between the sexes. This is reflected in an almost template-like composition of the grave goods. With some objects it is assumed that they were only made as grave goods from the start. The women were buried in festive dresses, jewelry, household items and textile-making equipment. Weapons and items related to fighting, horses and hunting were added to the men. But these stencil-like grave goods cast doubt on whether the people actually dealt with them in their lives. It is believed that not all men who were buried with weapons actually used them during their lifetime. And not all women who were given a distaff spun wool in their lives. Some are known to have taken the initiative and even commissioned the erection of memorial stones. In some women's graves scales and weights were found, which indicates participation in the trade. The Njáls saga and the Laxdœla saga , which were written down late, but are based on much older traditions, offer a critical view of the traditional distribution of roles . In both accounts of family feuds, it is the men who propel the plot of the story forward. A closer reading, however, shows that they are only puppets in the hands of women. It is they who, through their thirst for revenge, incite the respective men to feud without even taking part in an argument.

More frequent conversations with the same unmarried woman indicated that courtship would soon be possible. If she was already engaged, this led to a conflict with the fiancé. A ritual seizure was seen in a man laying his head on a girl's lap. Thord had threatened Orm if he didn’t miss the visits to Sigrid that had been promised to someone else.

"Þenna morgun hefir Ormur njósn af að Þórður mun brátt sigla. Hann lætur taka sér hest. […] Síðan tók hann vopn sín. Hann reið út til Óss og þangað í hvamminn sem Sigríður var. Hann sté af hestinum og batt hann. Síðan leggur hann af sér vopnin and gengur til hennar Sigríðar and setur hana niður and leggur Höfuð í kné henni and leggur hennar hendur í Höfuð sér. Hún spurði hví hann gerði slíkt ‚því að þetta er á móti mínum vilja. Eða manstu eigi ályktarorð bróður míns? Og mun hann það efna. Sjá þú svo fyrir þínum hluta. ' Hann segir: 'Ekki hirði eg um grýlur yðrar.' "

“That morning Orm heard that Thord was about to leave. He asked for a horse. [...] Then he took his weapons. He rode out to Os into the valley where Sigrid was. He got off his horse and tied it. Then he put down his weapons and went up to her, sat Sigrid down, laid his head on his lap and her hands on his head. She asked why he was doing this - 'it's against my will; and don't you think of my brother's last word? He'll hold it. Do what you think is right. ' He replied: 'I don't care about your nightmares.' "

Thord finds out about it, rides there immediately and kills Orm on the spot.

Rules in dealing with one another

Dealing with one another was determined by unwritten rules. The most important capital in society was honor and reputation. This not only affected the behavior on the thing, but even the way of greeting at the residential building. The visitor had to call the master of the house and the master had to step out of the house. It was considered gross impoliteness and disregard for the landlord to ride across his land without visiting him.

The seating arrangements in the hall were also precisely regulated. The landlord sat on a high seat, a seat with a high back, on one of the long walls of the house. The most distinguished guest's place of honor was on a high seat opposite him. The women sat on the narrow sides. Archaeological evidence suggests that the high seat could also stand in a corner. According to the finds in the ground (for example in Borg on the Lofoten), this corner was apparently intended for ritual sacrifices, so a kind of " Lord God corner ". It is assumed that the chief who presided over the ritual also had his high seat there.

Rules even applied to lying at anchor. Disregarding such rules could have fatal consequences: Þorleif the wise commanded a ship on which Erich, the son of Jarl Håkon, was also. It was very important to Erich that this ship should be next to the Jarl's.

“En er þeir kómu suðr á Mœri, þá kom þar Skopti, mágr hans, með langskip vel skipat. En er þeir róa at flotanum, þá kallar Skopti, at Þorleifr skyldi rýma Höfnina fyrir honum ok leggja or læginu. Eiríkr svarar skjótt, bað Skopta leggja í annat lægi. Þá heyrði Hákon jarl, at Eiríkr, son hans, þóttist nú svá ríkr, at hann vill eigi vægja fyrir Skopta; kallar jarl þegar, bað þá leggja or læginu, segir at þeim mun annarr verða verri, segir at þeir mundu vera barðir. En er Þorleifr heyrði þetta, hét hann á menn sína ok bað leggja skipit or tengslum, ok var svá gert. Lagði þá Skopti í lægi þat, he hann var vanr at hafa næst skipi jarls. "

“When they came to Möre, the brother-in-law of Jarl Skopti appeared there in a well-manned ship. As he rowed with his own to the fleet, he called to the Þorleif to vacate the harbor in front of him and leave the anchorage. Erich answered him immediately that Skopti should choose another anchorage. When Jarl Håkon heard that his son felt so powerful that he did not want to give way to Skopti, he immediately called over to let Skopti have the anchorage. He threatened that otherwise it would be easier for them to get worse, that there might be more blows. When Þorleif heard this, he instructed his people to loosen the anchor ropes, which they did. Skopti now went to the anchorage next to the Jarlship as he was used to. "

Erich did not forget that and later killed Skopti.

The worst abuse that could be done to anyone was to set up a bar of shame . Egill Skallagrímsson built it against King Erik the Bloodaxe:

"Hann tók í hönd sér heslistöng og gekk á bergsnös nokkura, þá he vissi til lands inn; þá tók hann hrosshöfuð and setti upp á stöngina. Síðan veitti hann formála og mælti svo: ‚Hér set eg upp níðstöng, og sný eg þessu níði á hönd Eiríki konungi og Gunnhildi drottningu '- hann sneri hrosshöfðinu inn á land -' sný eg ggja nvetta þessu nvetta essu land svo að allar fari þær villar vega, engi hendi né hitti sitt inni, fyrr en þær reka Eirík konung og Gunnhildi úr landi. ' Síðan skýtur hann stönginni niður í bjargrifu og lét þar standa; hann sneri and Höfðinu in á country, en hann travels rúnar á stönginni, and segja þær formála þenna allan. "

“He took a hazel rod in his hand and walked up to a rock spire that looked far into the country. He took a horse's head and put it on top of the bar. Then he made the feud and said: 'Here I am setting up the bar and turning this insult against King Erich and Queen Gunnhild.' He straightened the horse's head towards the interior of the country. 'I also turn around,' he went on, 'this insult against the national spirits who live in this country, that they should all go astray and find no resting place anywhere until they have driven King Erich and Gunnhild out of the country . '"

There was not always a curse attached to the establishment of the bar. But the runes that contained the information and the horse's head were essential.

The guest right protected the guest from attacks by the host. After Skallagrim recorded Björn from Norway, he learned that Björn had married his friend's sister against his will and confronted him. Björn admits this and concludes with the sentence:

"Mun nú vera á þínu valdi, hver minn hlutur Skal verða, en góðs vænti eg af, því að eg er heimamaður þinn."

“I am now in your power, whatever my fate may be. But I hope the best from you, since I am now your housemate. "

Gifts

Culture also included the emphasis on personal relationships, expressed through the exchange of gifts. The exchange of gifts was a central part of social communication. So it is said in the Havamál:

|

39. Fannk-a ek mildan mann |

I have never found such a mild |

It was a special honor to receive a gold ring from the king. It was carried on the arm. The giving of gifts was subject to strict rules, the violation of which could be a grave insult. So it came down to giving the right gift to the right person at the right time. So the lower rank was not allowed to give the higher rank weapons, only the other way around. The exchange of gifts for people of unequal rank also had to come from the higher ranking, since the exchange of gifts was a ritual to establish a friendship with mutual obligations, which the lower placed could not impose on the higher placed. The gift to the king was an exception. But only certain gifts were allowed for this ( konungsgjöf ). These were, for example, valuable sails, horses and falcons. But bears are also mentioned. Gifts were always reciprocal. When Thord wanted to buy a coat for his wife from Thorir, it was given to him, but something in return was expected.

"Þórir kveðst kenna Þórð og hans foreldra‚ og vil eg eigi meta við þig heldur vil eg að þú þiggir skikkjuna. ' Þórður þakkaði honum ‚og vil eg þetta þiggja og lát hér liggja meðan eg geng eftir verðinu. '"

"Thorir said he knows him and his parents - 'and I don't want to give you a prize, but ask you to take my coat.' Thord thanked him for it. - 'I want to accept that. I want to leave the coat here until I go and get some money. '"

Holy places

Another unwritten law that must be observed was that holy places could not be entered with weapons. Ingimundur obtained the Kinship Knobs sword by distracting his owner by talking when entering the temple, so that he went inside with the weapon.

"Ingimundur snerist við honum og mælti: 'Eigi er það siður að bera vopn í hofið og muntu verða fyrir goða reiði og er slíkt ófært nema bætur komi fram.'"

"Ingimund turned to him and shouted: 'It is not custom to bring weapons into the temple, and you expose yourself to the wrath of the gods, and it is unbearable unless repentance is paid.'"

Rules for Vikings

Even with the predatory Vikings there had to be social rules, about which there is not much information. But the various negotiations between opposing associations require that there be signs of negotiators and safe conduct. There was a truce. A sign was hung up on the camp and the gates opened, which showed that no military action was to be expected. It is also not known how the looted property was divided up. However, it seems to have been distributed unevenly, since at the end of the Viking Age there were Vikings who were too poor to buy land in England from their tribesmen and therefore returned to France, where they joined Rollo.

Time calculation

The calculation of time followed the then common pattern of counting according to the years of the respective ruler. A ubiquitous uniform time system did not yet exist. So one letter ended like this:

"[...] þettabref uar gortt ok gefuet a Marti Marcellini ok Petri. A fimtanda are rikis virððulegs herra Æiriks Magnus enns korunnaðða Noreks konungs. "

"This letter was issued on June 2nd when King Erik Magnusson was in his 15th year of reign."

The Landnámabók dates the first settlement of Iceland to the reign of Pope Hadrian II . The time calculation from the birth of Christ only came after Christianization. At first it was only an ideological instrument. The ecclesiastical and secular calendar coexisted for a while:

“[…] Et cancellarii [secundo kalendas] Decembris indiccione .iija. incarnacionis dominice anno .mo co liiijo. pontificatus vero domini Anastasii pape .iiij. anno .ijo. "

"November 30th, 3rd indiction , 1154 after the birth of our Lord, 2nd year of the pontificate of our Pope Anastasius IV. "

In Iceland, until 1319, calculations were usually based on the years of reign of the Norwegian kings or the Ladejarle, very rarely also on the basis of the times of the great Icelandic chiefs. The same is assumed for Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Greenland.

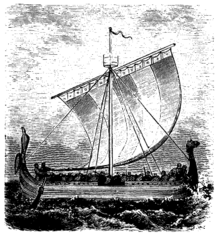

trade

A prerequisite for the activities of the Scandinavians in the Viking Age was the further development of ships. There are many names in the sources for different types of ships, which could not all be assigned to the archaeological finds. In any case, the longship and the Knorr were available for long overseas voyages . In addition to the skipper, the cook, the rowing crew (see below on the warships), the ships often had passengers ( farþegar ), sometimes a pilot ( leiðsögumaðr ) and an interpreter ( tulkr ) on board. Usually the owner of a merchant ship was also the skipper at the same time. Otherwise he had a representative ( lestreki ). The ships going to Iceland could also have multiple skippers. Merchant ships had four crew departments, each under a foreman ( reiðumaðr ).

In 845, it is said that Emir Abd ar-Rahman II entrusted one of his most experienced diplomats, Yahya ibn Hakam al-Bakri, known as Al-Ghazāl, with the task of traveling to the court of the king of the Madjus (as the Moors called the Northmen), to dissuade them from another attack on al-Andalus. There is even evidence of an Umayyad embassy among the Normans, which was probably about negotiations regarding the fur and slave trade. The historicity and the Norman negotiating partners are, however, controversial.

In the case of archaeological finds, it is difficult to differentiate between booty, gifts and merchandise. This is most likely possible on a trading platform. One of these was excavated in Norway. It is mentioned by Ottar place Sciringsheal , in the later norrönen literature Skíringssalr today Kaupang in Vestfold . The settlement was built around 800 and was used until 930/950. It was not inhabited all year round, but there were Norwegian and foreign traders there, as the graves show. The finds show a far-reaching connection with large parts of Europe. Arabic, Frankish and English coins and one from Haithabu were found. In addition, ceramics came from the Rhine area and jewelry from the British Isles. How far the journeys of individuals extended can be seen from a short note on a whetstone that was found in Gotland: “Ormila, Ulfar: Greece, Jerusalem, Iceland, Serkland ” (= Arab / Saracen world). Another trading center was identified in 2013 through the discovery of scales and a button in graves near Steinkjer north of Trondheim.

Trade trips by the Frisians to Denmark and the Kattegat were known even before the Viking Age . But the real boom came with the connection between the mouth of the Eider and the Schlei , a connection between the North and Baltic Seas and the founding of Haithabu by King Göttrik. Now larger trading areas were opened up: ceramics, glasses, millstones, church implements, jewelry and wine from the Rhine region, cloth from Friesland, jewelry from England, swords from the Franconian Empire. From the Arabs jewelry, rings, bowls, buckles and fittings, silk, probably also spices, wine and tropical fruits and apparently many silver coins were procured. Trade with Byzantium brought brocade and silk north. The Scandinavian merchants brought furs and slaves, initially via Western Europe and the Mediterranean, via Russia together with wax and honey to the Orient. The close connection between trade and robbery can be seen in the slave trade, whose goods usually came from north-eastern Europe. Iron bars from Norway, Småland and northern central Sweden are also known to be exported. Amber came from the southern Baltic coast, and walrus teeth and skins came south from the White Sea . During the excavations in Haithabu, jewelry articles made there were found for export. Long-distance trade was therefore a downright luxury trade for wealthy circles. It was followed by local trade around the trading centers, as can be seen from the valuable finds around Birka . So was Adam of Bremen reported that all of Sweden is full of foreign goods. There are no certificates for the transshipment of Arab goods to Haithabu and Western Europe. Haithabu did not have such a rich hinterland as Birka and flourished due to the transit trade at the point of contact between two traffic areas, the North Sea and the Baltic Sea.

The long-distance traders in the east were usually people from the area around Lake Mälaren and Gotlander . Whether and to what extent these traders were trading in the west, where the Frisians dominated, cannot be determined. Almost nothing is known about their ships, only their names ( snekkja, karfi, skúta, knörr, búza and byrðingr ). But we do know that they had sails and a side rudder. It is possible that the burial ships allow a conclusion to be drawn about the karfi , the most common ship used in Eastern trade, as the term κάραβος (kárabos), borrowed from Greek, shows. In any case, they were smaller and agile ships, like those used for the robbery trips. Due to their limited loading capacity, they could not keep up with the mass trade of what would later become the cogs.

A uniform commercial law that spanned the entire commercial network did not yet exist. You had to agree on the applicable law beforehand. Sometimes a customary law had already developed at the place of trade, which one adhered to. The forms of society that were more advanced among the Varangians in Rus also had no equivalent in Sweden. At most, there was a félag , a loot and trade community that included a common defense, a common profit, a common risk and a share in the ship. The only thing that can be deduced from the Viking Age rune stones is that the félag was initially only important for war journeys . Only the post-Viking period inscriptions extend the expression to trade. Apparently there was no professional trading stand yet. The mention of a trading guild in Sigtuna apparently refers to the Frisian trade, and it does not seem to have survived its decline. The merchants' guilds, whose purpose was mutual protection and the provision of replacement and assistance in the event of damage, were widespread in the Viking Age Frisian trade. This form of trade organization later penetrated the Baltic Sea region from the west and achieved successes that the former farmer-merchant had not been able to achieve.

FelagaR were men who pooled parts of their movable assets into common capital that served a common enterprise. They shared profit and risk. At the time of the second conquest of England by Svend Tveskæg and Canute the Great , the warlike importance prevailed in their followers. On the runestone Århus IV, the participants in the battle of the kings are referred to as félaga , as are the comrades in Toki Gormsson's fight and on the stone of Gårdstånga 2. The historical background of the construction time and the location of the stones far from the trading centers of Haithabu and Ripen make it It is probable that the other stones on which the word felagi appears, without the company being named, also belong to the campaigns. Later on, felagi developed into rowers , followers and friends. In the Hávamál the word was finally spiritualized into pure friendship. On the rune stone of Sigtuna, a partner of a member of the Frisian Guild is referred to as a felagi , so that only a trading partnership is possible here. The fact that, with the advent of the Hanseatic League, the term félagi , unlike Denmark and Iceland, did not survive, also suggests that in Sweden it mainly referred to trading companies.

In the 10th century, silver production in the Caliphate declined . Saxon silver gradually took its place. Up until 930, the coin finds in Gotland and Russia had roughly the same composition with many new Arab coins. After that, the supply of newly minted coins decreased and the proportion of old coins increased steadily. According to the coin finds of the Arab coins to the west, this supply must have ended around 930, the one from Russia to Gotland around 970. This gap has now been filled with the silver from the Harz Mountains, the coins of which subsequently came to Gotland in large numbers and were found in north-west Russia. This trade, which was often made by non-Scandinavian merchants, gradually weakened Birka's importance and favored Wollin. In the 10th century, political changes on the Volga made the Volga route impassable. In its place came the road across the Dnieper. At the same time, trade grew from southern Sweden and Gotland to southern Finland and the Baltic States. In the 11th century swords, spearheads, buckles and fittings for horse harness became the main export items. Many runic inscriptions testify to the role of the Gotland trips. The peak of trade with the Oder and Weichselland falls in the 10th and the beginning of the 11th century.

Birka was now off the prevailing trade routes and was finally abandoned towards the end of the 10th century due to constant raids. Even Sigtuna could not attain special importance like Birka in the past, even if a Frisian guild attested on a rune stone testifies to the continuation of the east-west trade. The focus was on Gotland.

Many Swedes were involved in the robbery trips from Denmark to England that began again at the end of the 10th century. A large part of the Danegeld was found in eastern Sweden . In Haithabu, the export trade gradually ceased around 1000. Only the Danish trade with England increased towards the end of the Viking Age in the time of Canute the Great . Evidence of this is the St. Clemens Dane Church in London, which is considered the merchant church of that time. Sweden's trade with Byzantium ceased in the second half of the 11th century and was, to a lesser extent, replaced by trade with Novgorod . The popular predatory trade also declined in the course of the consolidation of Russia and the tribes in the Baltic States. It was not until the 12th century that Gotland trade with Russia grew again, and the Gotlanders expanded their position in Novgorod again. At the same time, Gotland was able to use the trade line further west from the Lower Rhine via Dortmund and Soest to Schleswig and other Danish cities. This practically replaced the Frisian Baltic Sea trade .

In contrast, intra-Scandinavian trade took place on a smaller scale. He followed the navigable waters and the mountain ranges ( åsar ). The distribution of rune stones in Västmanland , North Uppland and Gästrikland characterize these ancient travel routes. The longest was probably the one from Trøndelag to Lake Mälaren . Iron bars from Dalarna were found that had been transported to Birka and on to Gotland. The traffic took place especially in winter when the waters were frozen over.

The trade with Christian merchants was tied to the fact that the Scandinavian merchants were either already Christians, which was largely the case according to the rune stone inscriptions, or at least had received the sign of the cross on their foreheads, the primsigning .

"Konungur bað Thorolf og þá bræður, að þeir skyldu Lata prímsignast, því að það var þá mikill sidur, bæði með kaupmönnum og theim mönnum he á Mála Gengu með kristnum mönnum, því að þeir menn he prímsignaðir voru, höfðu allt samneyti við kristna menn og svo heiðna, en Höfðu það að átrúnaði, er þeim var skapfelldast. "

“The king asked Þorolf and his brothers to accept the primsigning, because at that time it was common practice among merchants and those who served Christians. The men who bore the sign of the cross had free intercourse with both Christians and Gentiles and professed the faith that pleased them. "

activities

The success of the Nordmanns rested on their ships . In any case, there were no pure land wars in Norway like on the continent. All wars involved ships, even when battles were fought on land. Either a party had come with ships, or the losing party fled on ships, or the battle was decided by the fact that the enemy fleet was conquered, as in Sverre's victory over King Magnus in 1180 at Ilevoll (Trondheim). A king without ships was a powerless man in Norway. These were not just a means of transport, but part of the culture, as the ship graves show. The entire complex of ship, shipbuilding, ship equipment, nautical and shipping routes on the North Sea is dealt with in the articles Viking ship , Viking shipbuilding and the history of Viking shipbuilding .