Valhalla

Valhall ( old north. Valhöll , 'apartment of the fallen'), also Valhall , Walhalla or Valhalla , possibly linked to or identical to the palace of the gods Valaskjalf , is the resting place of fighters who fell in a battle and who have proven themselves to be brave in Norse mythology so-called Einherjer .

description

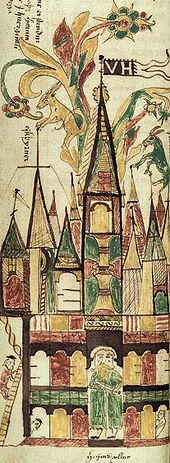

At the end of the mythical development, Valhalla is a magnificent hall with 540 gates through which 800 people can move in side by side. It is located in Odin's castle Gladsheim in Asgard in the realm of the Aesir . The roof of the hall should consist of shields that rest on spears as rafters, although there are sources that contradict this.

During the day, the Einherjer compete there in a duel. In the evenings, the fighters enjoy themselves with beer and mead , which the Valkyries hand them . But they also have the task of choosing the bravest of the fighters who fell on the battlefield and bringing them to Valhalla.

Odin and his wife Frigg live in the heavenly King's Hall . Odin is enthroned mighty and lofty on his high seat Hlidskialf and enjoys noble weapon games. A mighty deer antler hangs on the gable wall and reminds the warriors of past earthly hunting joys.

Fountains adorn the benches, and the hall is illuminated by the gleam of swords. A wolf hangs over the western gate, and an eagle hovers over it - the animals that accompany the god of battle on the whale site .

Walhall's cook, Andhrimnir ("sooty face"), has a black face because he looks for days into the cauldron in which the boar Sæhrímnir is prepared every evening. Sæhrímnir comes alive and consumed again every day. Odin, however, never eats the boar's meat, but always gives his share to his wolves. He is satisfied with the mead.

Myth development

The earliest mention of Valhalla can be found in Bragi's shield poem under the name Swölnirs (Odin's) Hall . The previous resuscitation of the fallen warriors by Hild to fight again (verse 230) has nothing to do with Valhalla, but belongs to the topos of ancient necromancy. It can only be assumed that the dead heroes will come to Valhalla in the 9th century. In the Eirikslied , Odin asks Sigmund and Sinfjötli in Valhalla to rise from their seats to greet Erik Blutaxt , who died in a battle around 954. The Eastern and Visigoths, on the other hand, believed that all the dead were underground or in a mountain. Regionally in Iceland and Sweden, the belief that you will die into a mountain has long persisted. It is also guaranteed that in some areas the dead were imagined living alone in their burial mound. In Sögubrot af Fornkonungum and Saxo Grammaticus , the father of Harald Kampfzahn , the warrior Haldan, who does not have children with his wife Gurid, is asked to offer the dead relatives at the Hel. So it is not reported that he and his relatives would come to Valhalla. Only his son Harald will come to Valhalla as a devotee to Odin. But here, too, a peculiarity can be observed: According to Saxo, the slain Harald Kampfzahn moves into an underground hall at the head of the dead on the battlefield, where he is to be given " comfortable seats ". In Sögubrot, on the other hand, the dead king is asked to “ride or drive” to Valhalla according to his choice . Sögubrot leaves open where Valhalla is and what it looks like there. Saxo's presentation probably reflects the older view. Because for the Goths, too, the place of the dead was in ᾅδης ( Hades , underworld), translated by Wulfila as halja ('hall'), with which the idea of a surrounding green field was connected. Saxo writes of Hading, consecrated to the Odin: Under the guidance of an old woman, he climbed into the misty depths “until they finally entered the sunny fields which the grasses brought by the woman produced” . After both had crossed a river gazed with weapons, they saw warriors playing weapons with one another. A high, insurmountable wall finally caused Hading to turn back and to ascend to the living. The old Baldr myth also contains a corresponding description of the place of the dead: The god Hermod rode north through dark, deep valleys for nine nights until he came to the Gjöll Bridge, which was guarded by the guard Modgudr and blocked by the Helgatter . Hermod rode over the bridge, went over the gate and finally came to a hall with his brother Baldr sitting on the high seat. Here, too, albeit tailored to Baldr, the subterranean hall with the high seat is the place for the (noble) dead, which is far to the north, deep underground. So the gods did not originally live with the dead.

It was not until the 10th century that it was reported that Odin was sitting with the Einheri in a high hall. The idea that the gods live alone in high castles or farms is probably the earliest historically tangible belief of the northern Germans. The ancient Guta saga reports that the people of Gotland “believed in groves and burial mounds, sanctuaries and staff enclosures and in the pagan gods”. This saga also mentions a Thorsburg (Thors borg) on Gotland, a massive, towering limestone plateau with a stone wall from the migration period. But the old Thjazi myth, as it was known in the north in the 9th century, the myth of the giants building castles for the Aesir and the myths of the Aesir conquest in southern Russia and Sweden, which Saxo Grammaticus and Snorri pass on, testify to the same Idea.

If one pursues this notion of the gods' dwelling further, it can be established that the Edda only speaks of a castle or a high courtyard as the seat of the gods. The dwellings of the gods, especially Odin's hall, are now poetically adorned: shields are the shingles, shafts form the rafters, Odin overlooks the world from his high seat Hliðskjálf, the events of which his two ravens tell him about; the sir gather in Odin's hall, the benches of which are adorned by the Valkyries for those arriving - without it being said that Valhalla is in heaven. On the contrary: the descriptions of Valhalla point to the old castle concept or a courtyard hall. This applies to the Völuspá , the Grímnismál , the Þrymskviða and the Vafþrúðnismál in the same way. Even the song of praise to King Hakon (Hákonarmál) from the middle of the 10th century does not contain any passage that could be understood in the sense of a heavenly Valhalla, when it says that the host of gods through Håkon and his great army (of the fallen) now grow. In this award song, the dead warriors ride "to the green gods' home", which only proves how strong the old belief in the gods and their castle or courtyard is still alive in the 10th century! The idea of a heavenly Valhalla must have arisen only later, so that the Icelander Snorri Sturluson (around 1200) in his Edda (Snorra-Edda) provided the old myths with appropriate additions. But with the exception of this late development, nowhere in the northern world is there a record of a heavenly dwelling of the gods. Saxo Grammaticus gives no information for Denmark, nor does the Ynglingatal from the middle of the 9th century, in which the royal dead are sent to "Lokis Maid" (= Hel), quite apart from the already described idea in Sweden and Iceland that the dead “die into the mountain” or live in burial mounds. Apparently, the idea of a heavenly Valhalla is only a late regional development and a Skaldic stylization of the belief that was originally widespread in the north, not yet observed in the 10th century, that the sir live in castles or farms with a long view.

However, it is difficult to say when the belief arose that Odin called brave warriors to his hall. According to Snorri's legend, the dying Odin had himself drawn with the point of his spear and declared all men who die in arms to be his own. He said he was going to “go to Goðheima (home of gods) and there will welcome his friends”. He also said, “Everyone should come to Valhalla with wealth as rich as he was with him at his stake. There he should also have the treasures that he had buried in the earth ”. The belief that Odin called the dead warriors of the battlefield into his (castle or court) Valhalla may only have arisen at the end of the migration and more or less limited to the warrior caste that was now emerging, which, however, is traditional at the royal court dominated. This Valhalla of Odin now - as the hall of the fallen - attracts ideas that were originally connected to their subterranean place of death: A sword-freezing river now also surrounds Valhalla, over which there is a bridge that is blocked by the whale gate. This belief in a warrior whale hall in Odin's castle or court, which was slowly emerging in the age of powerful army kings with their large following, cannot, however, have been widespread to the same extent everywhere in the north. This is already proven by the old Swedish Ynglingatal from the middle of the 9th century, which only Hel knows as a place of death for warriors and kings. Even the Dane Saxo Grammaticus only speaks of subterranean places of death - those for warriors with pleasant green areas and for envious people in snake-deep caves in the north. A landscape description of the emergence and spread of the new belief in a warrior whale hall above the earth does not seem possible today. In contrast, the belief in a heavenly Valhalla of gods and heroes can only be viewed as a late regional development of the Germanic belief in heroes, which was not yet observed in the 10th century. None of the continental and Anglo-Saxon sources indicate that the Vikings calmly looked at a heroic death with the prospect of entering Valhalla. Rather, they avoided the perceived danger and saved themselves without further ado by fleeing or ransom.

environment

The goat Heidrun grazes on the gold-covered roof . She gives the warriors that delicious drink in inexhaustible abundance, which preserves their heroic nature. The goat feeds on the tree of life, the world ash. Nobody knows how far the roots of the world ash ( Yggdrasil ) flow. Iron and fire have always been unable to harm the ash. The crown is very high and covered in soft mist. The dew that arises moistens the valleys. The lively spring of the Norn Urd sprouts at the feet of this mighty tree. The squirrel Ratatöskr lives, plays and terrorizes in the branches of the ash .

Around the hallowed halls lie the houses and properties of the remaining gods: Thor's Thrúdheim with his house Bilskirnir , Baldur's house is called Breidablik .

Rapporteur

The only warrior who, according to legend, ever managed to leave Valhalla again after his death was the shining hero Helgi . When Helgi is buried in his mound of death, Odin takes him out of his earthly being and awards him with a favor like never before. On the ground, the maid of Helgi's beloved Sigrun sees Helgi, who is badly bleeding and wounded, riding past his burial mound. He tells her that if her mistress wishes he will return to his burial mound the next day. He sends the maid with the customer to her mistress. The next day Sigrun went to her lover's burial chamber, and the maid was right. She falls around her lover's neck full of joy, and the former couple spends one last intimate night of love before the lover returns to Valhalla at dawn, before the first cock-crow can be heard in Asgard.

See also

literature

- Ludwig Buisson : The picture stone Ardre VIII on Gotland. Series: Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class, Third Part No. 102. Göttingen 1976

- Grettis saga: The story of the strong Grettir, the outlaw. In: Thule Collection, Vol. 5 Düsseldorf, Cologne 1963.

- Gutalag och Gutasaga , utg. Af Hugo Pipping, København 1905–1907 (Samfund 33)

- Sögubrot af Fornkonungum . In: Sögur Danakonunga , udg. av C. af Petersens and E. Olson, København 1919-1925 (Samfund 46.1). Danish translation: C. Ch. Rafn, Nordiske Kaempe-Historier , Vol. III (1824).

- Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum , rec. et ed. J. Olrik et H. Ræder, Vol. I (1931), Lib. VII, cX; Lib. VIII, c.IV.

- H. Uecker: The old Norse funeral rites in literary tradition (Diss. Munich 1966).

- Gustav A. Ritter: Walhalla and Olymp ; Merkur Verlag (ca.1900)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alexander Jóhannesson, Icelandic etymological dictionary p. 164.

- ↑ This is the keyword in the German dictionary , the most commonly used form in poetry.

- ^ The younger Edda, p. 221, Str. 231

- ↑ Eyrbyggja saga: "Thorolf Helgafell (Heiligenberg) named this hill and believed that he would go into it when he died, and so did all relatives on the headland." And later: "One autumn evening the shepherd wanted Thorsteins north of Helgafell drive the cattle home. Then he saw the hill open on the north side. He saw great fires in the hill, and heard from it a cheerful noise and the sound of horns. And when he listened carefully to see whether he could distinguish a few words, he heard how they greeted Thorstein and his companions and said that he would soon be sitting on the high seat opposite his father ... "

- ↑ Gretti's saga, Chapter 18.

- ↑ Sögubrot af Fornkonungum, pp. 1–25.

- ↑ Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum, Lib. VII, cX, l ff. (Pp. 206 ff.); Lib. VIII, c.IV, 1 ff. (P. 217 ff.)

- ^ Gesta Danorum Lib. I, c. VIII, 31

- ↑ Gylfaginning chapter 49

- ↑ Roesdahl sees here a connection to the rich graves of distinguished warriors with weapons and equipment. Else Roesdahl: Nordisk førkristen religion. Om kilder og metoder . In: Nordisk Hedendom. Et symposium. Odense 1991, pp. 293-301, 295.

- ↑ Buisson p. 100 ff.

- ↑ Horst Zettel: The image of the Normans and the Norman incursions in West Franconian, East Franconian and Anglo-Saxon sources from the 8th to 11th centuries . Munich 1977, pp. 148-152.