Norse mythology

As Norse mythology refers to the totality of the myths that the sources of the pre-Christian Scandinavia are occupied.

General

The Nordic myths are in part very similar to the continental Germanic myths . Today it is generally assumed that the society of gods was originally the same. Nevertheless, cults , names and myths in the various rooms have diverged over time.

Norse mythology was never based on any religious society or any related religious system. So it was never anything like a religion in the modern sense. There was also no authority that determined the content of the beliefs. The myths were more of a theoretical superstructure for certain cult forms and had little to do with belief in our sense. Nevertheless, there are always attempts in research to determine what the “original” and “real” beliefs were. Such a quality judgment can hardly be made, especially since a religion is always experienced as "real" by those who practice it.

There is very little written evidence from the time of the mythical cults. These are the runes carved into metal or stone . Most of the sources, however, come from Roman and Christian scriptures. These are neither first-hand nor neutral. The coherent presentation and the encyclopedic character of the Völuspá are not attributed to the previous oral tradition. One must also take into account that the Scandinavian poets used elements of the Christian religion without adopting its content.

Archaeological sources

Indications of religious ideas from prehistoric times can also be read from Bronze Age artefacts. Well-known are bowl-shaped depressions in rocks that are associated with victims. Rock carvings suggest shamanistic - magical practices. It cannot be determined whether the content of the myths has anything to do with what has come down on us. The wheel with four spokes carved into the rock suggests a sun cult in the Bronze Age, for which a mythical basis has not been handed down. The same goes for miniature axes that are associated with lightning. The Trundholm Sun Chariot, a 57 cm long bronze model of a horse-drawn chariot found in 1902 on Sjælland , Denmark, which dates from 1500 to 1300 BC. In any case, no sun cult is documented.

From a religious-phenomenological point of view, it is not completely certain that gods as living beings were already associated with the Stone Age religions . It is also quite possible that natural elements such as lightning, trees, stones, earth and water were themselves considered to be alive. Gods as persons are documented in the Bronze Age by rock drawings and bronze figures. Small boats made of gold and other objects are now found in large numbers, suggesting victims. Sacrificial vessels on chariots indicate fertility cults , which are mythologically associated with the Pan-Germanic deity Nerthus according to Tacitus .

The cremation , the v in the second half of the 2nd millennium. Chr. Became customary, is interpreted as a means of liberating the soul from the body for a life beyond.

From the 4th century AD, ship burials come in various forms. People are buried in full clothing and with rich gifts. Coins are found in the mouth of the dead, analogous to the obolus from Greek mythology , with the help of which he is supposed to pay for the passage of the soul into the realm of the dead. It is unlikely that the same very special motif should have emerged at this time regardless of the continental culture, so that a motif migration from south to north can be assumed.

Further sources are the Scandinavian bracteates with depictions of gods and runic inscriptions as well as all kinds of votive offerings .

All of these archaeological testimonies require written sources for their concrete interpretation. When Snorri Sturluson wrote his skald textbook around 1225, the mythological material described was known from Scandinavia to Bavaria. For example, he describes the Midgard serpent as an animal that lies in the sea around the world and bites its own tail. This text interprets the depiction of the ring-shaped snake biting its tail on the gold medallion from Lyngby from the 5th century, on the English stone cross fragment from Brigham from the 8th century, also the ring in a pillar service of the Neuwerkkirche in Goslar from the 12th century . Century and on the late Romanesque baptismal font of Fullösa in Skåne . Its tradition is the most important key to the Germanic iconography of myths. Pictorial representations that cannot be assigned to any textual tradition, as applies to the rock carvings of the Bronze Age, cannot be interpreted beyond the specific object of the representation.

Written sources

General sources

The oldest sources of myths north of the Alps date from the 1st century AD and were handed down by Tacitus . Other sources are votive stones of Germanic soldiers in Roman service. They are often difficult to understand because they are very short and require knowledge of mythical connections. In addition, they usually designate the Germanic gods with the Latin names of the corresponding Roman deities. Additional sources include authors such as Procopius , Jordanes , Gregory of Tours , Paulus Diaconus and Beda Venerabilis , and resolutions from church synods and laws, especially from Burchard von Worms , papal circulars and sermons. They allow conclusions to be drawn about the religious practice of the common people on the Germanic continent, which is then followed by news about later times.

Sources in a Germanic language, such as the Merseburg magic spells , the text on the Nordendorfer clasp , the Anglo-Saxon family tables , glosses with people and place names and the allusions in the heroic sagas are extremely rare . However, all of these sources relate to myths and religious practices of the continental Germanic tribes, and the conclusions drawn from them cannot simply be transferred to Scandinavia despite the relationship.

Scandinavia is more richly blessed with written sources, mostly in Old Icelandic . Above all, there is the song Edda , the prose Edda of the skald Snorri Sturluson, whereby it must always be taken into account in his texts that they were written in a culture that was already influenced by Christianity. But also other skaldic and prose texts as well as Latin reports such as those of Adam of Bremen , Thietmar von Merseburg , Saxo Grammaticus , the Vita Ansgarii of Rimbert . Even in Sami and Finno-Ugric mythology there are characters that have North Germanic counterparts: Hora-galles corresponds to Thor, Väralden olmai (Isl.veraldar guð, Frey), Biegga-galles (wind god, storm god, Njörd or Odin) . The shamanistic Odin and the way in which he receives his special gift of vision is most likely of Finno-Ugric origin.

It is controversial whether what the learned Norwegian and Icelandic sources report about Norse mythology can be traced back to influences of Greek mythology and Christian thought . It certainly did not belong to the faith of the people. Some things can also be based on misunderstandings by Christian authors about mythical ideas and contexts. Sørensen believes that the Edda songs genuinely reproduce pagan tradition: On the one hand, the portrayal of the gods contains no reference to Christianity, not even to Christian morality. On the other hand, Snorri himself emphasizes the sharp difference between what he writes and Christianity:

“En ekki er at gleyma eða ósanna svá þessar frásagnir at taka ór skáldskapinum fornar kenningar, þær er Höfuðskáld hafa sér líka látit. En eigi skulu kristnir menn trúa á heiðin goð ok eigi á sannyndi þessa sagna annan veg en svá sem hér finnst í upphafi bókar. "

“The legends told here must not be forgotten or belied by banning the old paraphrases from poetry, which the classics liked. But Christians should not believe in the pagan gods and in the truth of these legends in any other way than as it is to be read at the beginning of this book. "

So Snorri understood his tradition as genuinely pagan and dangerous for Christians. An influence can be assumed in particular for the establishment of "temples", which are mentioned in Latin texts. There is no corresponding word for the Latin word templum in norrön , and not the slightest archaeological traces of pagan places of worship have been found. It is therefore not possible to say with any certainty which object the authors have used the term templum . Everything speaks for a sacrificial cult in the open air with a feast in the Goden's house . However, there are also large halls for the feast (e.g. Borg on Lofoten with 74 m length, Gudme on Fyn and Lejre on Zealand with 47 m). The place names on -hov also indicate such central places of worship. For all that is known, the building temple in Uppåkra was an exception. The belief among the people about the souls of the dead and the natural phenomena corresponds substantially to what was believed in Europe, as evidenced by the matching popular belief lately and also the similar nomenclature for albums , Dwarves , Night Mare , elf and sprite is confirmed . News of such commonalities in the beliefs of the early Germanic times can be found in the common tendency to worship the sun, the moon and fire beyond trees and rivers. A systematic mythology on which popular belief is based cannot be developed from the sources. The traditions were also not uniform. For example, Snorri writes. B. in Gylfaginning on Odin:

"Ok fyrir því má hann heita Alföðr, at hann er faðir allra goðanna ok manna ok alls þess, er af honum ok hans krafti var fullgert. Jörðin var dóttir hans ok kona hans. "

“He can be called all-father because he is the father of all gods and men and everything that was created through him and his power. Jörð (earth) was his daughter and his wife. "

and shortly afterwards:

"Nörfi eða Narfi hét jötunn, he byggði í Jötunheimum. Hann átti dóttur, he Nótt hét. … Því næst var hon gift þeim, he Ánarr hét. Jörð hét þeira dóttir. "

“Nörfi or Narfi was the name of a giant who lived in Riesenheim. He had a daughter named Nacht ... In her second marriage she was married to someone named Ánnar. Jörð (earth) was the name of her daughter. "

So here Snorri has unconnected two different traditions about Jörð's parents. A vertical view of the world with gods in the sky and a horizontal view of the world with the residence of the gods in the center of the earth disk are also side by side. Baldur lives in Breiðablik, Njörd in Noatún and Freya in Folkwang, all located in heaven. On the other hand, it is said that the Aesir built a castle Asgard in the middle of the world and lived there. It is argued that both are different pagan traditions and that the vertical worldview reflects a Christian influence.

More recent research sees the influence of Christianity less in the intrusion of Christian motifs into pagan myths than in the manner of representation. Snorri Sturluson was trained in Central European thinking with precise definitions and categories. That rubbed off on the representation of the material. Hennig Kure has shown this with an example: Snorri refers to the elder Gylfaginning in Grímnismál. There it says in stanzas 25 and 26:

|

25. |

25. |

Snorri now paraphrases this source in Gylfaginning as follows:

"Geit sú, he Heiðrún heitir, stendr uppi á Valhöll ok bítr barr af limum trés þess, he mjök he nafnfrægt, he Læraðr heitir, en ór spenum hennar rennr mjöðr sá, he hon fyllir skapker hvern dag . Þat er svá mikit, at allir Einherjar verða fulldrukknir af . … Enn er meira mark at of hjörtinn Eikþyrni, er stendr á Valhöll ok bítr af limum þess trés , en af hornum hans verðr svá mikill dropi, at niðr kemr í Hvergelmi, ok þaðan af falla þær ár, he sváð heita: Síðr ár ... etc."

“The goat called Heiðrún stands on top of Valhöll and eats the leaves from the branches of the tree, which is very named and is called Læraðr. Mead runs out of her teats and fills the vessels with it every day. That is so much that everyone in the family gets drunk with it. ... That is more remarkable about the deer Eikþyrnir. He stands on Valhöll and eats from the branches of this tree and from his horn so many drops come down to Hvergelmi, and from it the rivers that are called Síð, ... etc. "

The vagueness of the myth is made clear in Snorri. The word "á" in the second line, which can mean "on, next to, near", becomes "uppi" - "on top" with Snorri. The unspecified “Lærað” is defined as a tree. Gylfaginning does not say what the goat eats from the branches, Snorri states: it is leaves. Snorri also first clarifies what the mead is running out of. Gylfaginning never runs out of mead. Snorri adds that the Einherjer get drunk. All water in Gylfaginning comes from the drops of the deer antlers. Snorri enumerates all the rivers. Nothing remains in a mythical limbo, everything is precisely defined. In this Kure and the research cited by him sees the main influence of Christian education on the representation of pagan myths and points out that current research also looks at these myths through the glasses of Snorri.

Inscriptions can be seen as further written sources. They can be found on bracteates, consecration, votive and image stones .

Sources for the names of the gods

In Scandinavia, the gods Frey, Freya, Njord and the sir, especially Thor, were sworn by the gods. Egil Skallagrimsson called down a curse from Odin, Frey and Njörd in Egils saga 934, and in Skírnismál curses are conjured up in the name of Odin, Thor and Frey. For Trondheim, toasts for Odin, Njörd and Frey have been handed down to the victims for the 10th century . The Flateyjarbók also names Odin, Frey and the Aesir. Even Adam of Bremen called Odin, Frey and Thor as gods in connection with the Feast of Sacrifice of Uppsala . Thor is also mentioned in the temple of Håkon Jarl in Ark.

The translation of Roman days of the week into a Germanic nomenclature reveals which Germanic gods were seen to correspond to the Roman ones. This mercurii became onsdag ( Wednesday ), the day of Woden / Odin, because both led the dead to their new abode. This Jovis became Thorsdag ( Thursday ), which is an equivalent of Jupiter and Thor. Thor could also be identified with Hercules . What was a club to one was awesome to another. This Martis was changed to Tisdag ( Tuesday ), with which Mars and Tyr, a very old god of war, were put in correspondence.

According to Tacitus, certain Germanic peoples worshiped the goddess Nerthus , who corresponds to the god Njörd in the north. It is conceivable that the goddess of fertility among the Suebi in the neighborhood, whom Tacitus calls Isis, is identical to this Nertus. It is also uncertain whether Frey, Freya and Ull are proper names in the sources or not rather names for gods with other names, as is known in the land of God or Ásabraqr for Thor ("Þórr means Atli and Àsabragr" is called in the Prose Edda ). It looks as if there was a trinity of main gods, a sky god (first Tyr , later Thor ), a male / female for the earth, to which the sea belonged, and fertility ( Nertus, Njörd, Frey, Freya ) and an underground god of the dead ( Wodan, Odin ), whom one invoked in war and danger.

Procopius reported in the 6th century that the inhabitants of Thules (Norway) worshiped a large number of gods and spirits in the sky, in the air, on the earth, in the sea and in springs and rivers. Sacrifice to them all, but that Ares (Mars) - that is, Tyr - is their highest god, to whom they sacrificed people.

The Saxon baptismal vow , which is handed down in a Fulda manuscript from the 8th century, makes it possible to get to know the names of the most important gods for the Saxons . It reads: "I contradict all works and words of the devil, Thor, Wodan and Saxnot and all fiends who are their companions".

In the Merseburg magic spells , the gods Phol (Balder), Uuodan (Wodan), Sinhtgunt (controversial, but probably the moon), Sunna (sun), Friia (Isl. Frigg also Freya) and her sister Uolla (Isl. Fulla) are mentioned .

Certain god names often appear together, Njörd, Tyr and Thor , or Freya, Ull and Thor . According to the Völuspá , the world was created by Burr's sons Odin, Vile and Ve , and the people received their lives from Oden, Höner and Lodur .

Even the place names research promotes ancient gods name to light: Thor , Njord , Ull , Frey , Odin , Tyr , Frigg , Freya , with the Swedish nickname heme and Vrind , possibly Vidar, Balder, Höder and Skade . From the names of the families of gods, gud, as, dis , probably also van occur.

The myths

On the basis of the votive texts one can assume a balanced and confident relationship with the fate-determining powers among the peasant population. The mythology handed down by the skalds as presented in the Edda songs is completely different . A deep pessimism prevails here.

The Germanic gods are based on three sexes, all of which arose from the primeval chaos Ginnungagap and the primeval cattle Audhumbla : The sex of the giants and monsters, to which practically all evil beings belonged, who were also held responsible for natural disasters, came up first World. This gender has the power to destroy the world. To prevent this from happening, Vanes and Aesir were created. They keep everything in balance until the fate of the gods is fulfilled in a final battle, as a result of which there is a war between the giants and the Asen-Wanen League, which the fallen human warriors join and in which the whole world is destroyed to be born again.

The Wanen, the second oldest sex, were revered as extremely skillful, earthbound and wise and lived forever unless they were slain. The sir, the youngest generation, were considered to be extremely courageous and strong, but not very clever, which can also be read in the Edda. They owe their eternal life to a drink that made them somewhat dependent on the Vanes.

The main god of the Aesir was Odin, originally perhaps Tyr. The main god of the Wanen was the sea god Njörd and his twin children Freyr and Freya. Aesir and Wanen fought a great war in which the Aesir emerged victorious, with the Wanen still holding a respected position. Both sexes lived reconciled and side by side until the Christianization of the Germanic peoples began. This also gives rise to various creation myths: both Tyr and Odin were the creators of the first humans. Odin was originally the main god of the West Germans, and he spread northward across Europe. Originally Nerthus played a major role for the Northern Germans, but their god of war Wodan merged with the god of war Odin early on and thus became the main god. The East Germans also eventually took over Odin as their main god. Therefore, in the North Germanic religion Odin is always regarded as the supreme god.

Odin was the god above all other gods. Odin was first and foremost the god of war and death, and only secondarily a sage. The name "Odin" is derived from the Old Norse word "óðr", which means "wild, furious". Hence he was the god of ecstasy and frenzied struggle. He was not a Nordic, but a common Germanic god. He was also the chief god of the Angles , the Saxons , who called him Wodan, which is confirmed by inscriptions. The legend about Odin goes back a long way, because the Romans already knew that the Germanic peoples worshiped a god who resembled their Mercurius. Odin only had one eye, the other he had pawned to Joten Mimir , who commanded the fountain of wisdom on the tree of life Yggdrasil for what he was allowed to drink from the fountain - so he sacrificed his physical eye for a spiritual one with which he could see things that were hidden from others. He had also learned the magic of runes from Mimir. After the Völuspá, Odin had once caused the first war: “Odin hurled the spear into the enemy. That was the first battle of the peoples. "

As an ecstatic and a magician, Odin was able to change his form. It is not known where this shamanistic trait in Odin comes from, possibly from the east, where shamanism was widespread.

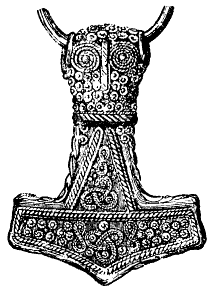

Thor was above all the god of the peasants. Its most important quality was its tremendous power. In addition, Thor had his hammer Mjolnir . Thor protected both gods and humans against the Joten , the hostile forces in the world. Thor's battle with the Midgard Serpent is the myth's favorite topic. This was a pus-spewing worm out in the ocean that was so long that it encompassed the world.

Odin and Thor were among the sir . This group of gods also included Balder , Heimdall , Loki , Bragi and Ullr . Frigg , Odin's wife, Siv , Thor's wife, and Idun were Wanen . There were also Norns , followers and Valkyries . They all had their task and role in the social world order as well as in the description of natural events. The Norns Urd , Verdandi and Skuld weave the thread of every human being. The subsequent spirits are spirits that accompany the people, the Valkyries of Odin's messengers. There are also other beings in nature: dwarves, elves and ghosts . The Joten were the main adversaries of the Aesir. They symbolized the uncontrollable forces of nature. Their progenitor was the primordial giant Ýmir , who was the primordial ground of the created world. When Odin killed Ýmir his blood became streams, rivers and the sea, his bones became stones, his flesh the earth and his hair the grass and the forest. His skull is the vault of heaven. However, the first humans, Ask and Embla, were created by Odin. The Wanen were another family of gods. They included Freyr and Freya as well as their father Njörðr , who grew up in Vanaheimr . The Vanes were gods of fertility. There was war between Wanen and Asen, but it ended with an alliance. There is speculation about a historical background, namely that warriors who believe in ace, have subjugated farmers who believe in vanity, or simply that the cult of vanes has been replaced by an ase cult, or that different life plans should be juxtaposed here.

The worldview

The worldview of the inhabitants of Scandinavia was strongly influenced by their myths and legends , although it is unclear to what extent their ideas were widespread among the population. The traditional myths describe what was recited in the royal court society, a warrior caste. Asgard was at the crossroads of the world, where the warlike gods, the Aesir, and the Vanes were based. Each of them had their own domicile and so ruled: Odin in Hlidskjálf, Balder on Breiðablik, Freyja in Fólkvangr, Freyr in Álfheimr, Njörd in Nóatún, Thor in Thrúdheimr and Heimdall at Himinbjörg Castle. The realm of gods and the world of mortals were connected by Bifröst , a rainbow-like bridge. Midgard was where the people were at home. It was surrounded by a vast sea that housed a gigantic serpent beast, simply referred to as the Midgard Serpent . Far in the distance was the outside world of Utgard. All sorts of monsters and giants lived here who were hostile to gods and men and were just waiting to strike on the day of Ragnarok . Deep under the cold earth, the realm of the dead was guarded by the goddess Hel . Hel was a deity, one half of whose body reflected a beguiling young woman, while the other side showed an old skeleton, which symbolized everything that is transient. In Asgard the world tree also grew, which was called Yggdrasil . This extremely gigantic tree was connected to Midgard, Utgard and Helheim through its roots and held the structure of the world and its order together. The water source of the goddess of fate lay in front of the world ash. The world tree was exposed to immense hardships: four deer tugged on its buds, the Lindwurm Nidhöggr gnawed at the roots and on one side the rot was already eating its way into the tree of life.

Fate of the world

In the Snorra Edda and in the Ynglinga saga , Snorri Sturluson has evaluated the mythical accounts found in older Icelandic poetry, especially the Song Edda . It may well be that he did not always correctly convey the pagan conception.

- The creation is reproduced in the Germanic history of creation .

- The end of the world is shown in Ragnarök .

There are other myths in Eddic poetry.

Other myth complexes

Genealogical myths of origin

Genealogical origin myths are historical myths that usually had to legitimize the rule of a royal clan.

Sæmundur fróði, father of Icelandic historiography (1056–1133), constructed a family tree of 30 generations for the Danish kings, which he traced back to the Skjöldungen and Ragnar Lodbrok . He was succeeded by Ari fróði for Harald Fairhair with an ancestral line of 20 generations to the mythical kings of Sweden , who should descend from the god Yngvi / Freyr , a main god of Uppsala . This formation of myths persisted for a long time, with the later kings trying to trace them back to either King Harald or King Olav the saint , although they certainly did not descend genetically from them.

The same can be seen in England. Early genealogies went back to Wodan (Odin) and Frealaf. West Saxon genealogies in the Life of King Alfred (c. 893/94) lead the West Saxon kings before Alfred back to Adam for the first time via Beaw, Scyldwa, Heremod, Itermon, Haðra, Hwala, Bedwig and Sceaf (ing). This also stands for the West Saxon King Æthelwulf in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , which began in 892. By aligning the genealogy with the Beowulf , Old English historiography constructed a common origin for Danes and Anglo-Saxons . In the 12th century the mythical connection to Troy and King Aeneas followed . Previously, the Franks had already established their legal succession to the Romans with their mythical descent from the Trojans.

Myths of origin for peoples

There is a group of historical myths whose social function consists in establishing the identity of a people. These myths depend on credibility within the historical time horizon, which is why they associate historical persons with mythical events. A typical example of this is the Faroese saga . But even the Landnámabók is no longer regarded as a historically accurate report on the settlement of Iceland .

One can also include the euhemeristic transformation of gods myths into historical myths for peoples, such as the Ynglinga saga of Heimskringla .

According to the prologue of the Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson , Odin was not a god, but a king. After him, King Odin Saxland subordinated his three sons: Ost-Saxland received his son Vegdeg , Westphalen received Beldeg and Franconia the son Sigi . Vegdeg's son was Vitrgils . His two sons were Vitta , the father of Heingest and Sigarr , the father of Svebdeg . In Anglo-Saxon sources the first original king and Wodan descendant is also Swæfdeg . There the first members of the Wodann descendants are shown with Wägdäg, Sigegar, Swæfdäg and Sigegat . Tacitus too is based on the original division of the northern Alpine region among three sons of Mannus . Even if the names and areas are different, the basic structure is similar.

Aitiological myths

The aitiological myth is about myths that are supposed to justify natural events or cults. The most famous myth is that of Mjölnir , with which Thor creates lightning. But there are other myths that fall into this group.

The name Helgi in the three heroic songs of the Edda Helgakviða Hundingsbana I , Helgakviða Hundingsbana II and Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar originally had a sacred meaning and referred to a person who was sanctified, consecrated. Beowulf gives the name Hálga again. Helgi got its name after the Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar from the mythical Valkyrie Sváfa . Helgi was killed by Odin's spear in the shackle grove, but was reborn. Linguistic research suggests that this is the victim in the Semnonenhain , a cult of the Suebi when they were still settled in Brandenburg and reported about the Tacitus.

The myth about Balder , who was killed by a mistletoe and then rises again, is one of the natural myths that support spring and growth.

For the cult of Odin, the Odin's spear was used to kill the victim. There were several myths surrounding this ritual, not just the Helgilied . Odin threw his spear Gungnir over the Wanen and started the first battle. The spear came from the dwarves and had been given to him by Loki.

Age of Myths

No reliable statements can be made about the age of the Nordic myths. The first question to be answered is what exactly one is asking for. The further you go back, the more sparse the building blocks will be that can be found in the final version of the Edda songs. Even if one ascribes the colorful variety of the songs to the imagination of a courtly intellectual poem, which was formulated by the skalds in the retinue of Olav the Saint , this says nothing about the time of the creation of the motifs that the skald has put together and his own transformations. These ideas must be a few hundred years older in order to be able to spread throughout Northern Europe in such a way that they were present in every listener of the Skaldendichtung and his Kenningar . Probably the oldest known depiction of the Mitgard serpent on the medallion of Lyngby from the 5th century should already have a long tradition behind it. On the other hand, for linguistic reasons ( syncope ) as well as for sociological reasons, a large part of the essential content of the songs of the gods cannot be assumed to date from a time before the 9th century. Because it is largely a matter of the seal of a warrior class. The idea of Valhalla as a place where the warriors who fell in battle enjoy themselves with fighting games is typical. Women have no chance of coming to Valhalla. When Håkon the Good fell in 961, Hákonarmál was written about him after his death. Håkon was a Christian, but the poet lets him move into Valhalla, which suggests that the Valhalla concept is very old. However, the warrior caste only became so established in the 9th century that it was able to form its own myth. None of the continental and Anglo-Saxon sources indicate that the Vikings calmly looked at a heroic death with the prospect of entering Valhalla. Rather, they avoided the perceived danger and saved themselves without further ado by fleeing or ransom. But the creation of the characters acting in the myths, their traits and their meaning in the pantheon must be distinguished from this myth-making process. These elements can be much older and even have been common property of the Early Iron Age, from which the poets then made use.

Another example is the one-eyed Odin who hangs on a tree for 9 days and 9 nights. Adam von Bremen's description of the festival of sacrifice in Uppsala, where animals and people were hung from trees , shows that this element is very old .

“The sacrificial ceremony is as follows: nine of each type of male living being are offered; it is customary to reconcile the gods with their blood. The bodies are hung in a grove surrounding the temple. This grove is so sacred to the heathen that it is believed that every single tree in it has gained divine power through the death and decay of the sacrifices. Dogs, horses and people hang there; a Christian told me that he had seen 72 corpses like this hanging randomly next to each other. Incidentally, at such sacrificial celebrations, one sings all sorts of indecent songs, which I would rather keep quiet about. "

One-eyedness and tree sanctuaries are very old elements, which certainly had many generations behind them as early as the time of Adam of Bremen , and Odin is considered to be the main god for Uppsala. But nothing is said about the age of the etiology . The pursuit of wisdom as the reason for this picture is certainly not as old as this picture and belongs in a social context with pronounced intellectual demands, be it in Norway or imported from the continent. Odin's acquisition of the runes on the one hand and the thesis that the runes were developed based on the Roman Capitalis monumentalis on the other hand leads to the fact that this part of the Odin myth only occurs after contact with the capitalis monumentalis and the subsequent development of the runes may have arisen.

Another example is the Helgakveða Hundingsbana II (a hero song from the older Edda ), the most ancient Helgilied, in which a fettered grove is mentioned, which is considered to be identical to the Semnonian-Suebian fettered forest reported about Tacitus. Although Helgi got his nickname from his enemy Hunding , Hunding does not play a role in the Helgilied. This means that in the course of tradition history has been subject to major changes. Incidentally, the transport of names can be proven here: In the story of Helgi, three people appear with the name Helgi: Helgi Hjörvarðsson , Helgi Hundingsbani and Helgi Haddingjaskati . The Valkyrie demonic lover of the first Helgi is called Sváva , a non-Scandinavian name that comes from southern Germany, Sigrún is the lover of the second Helgi and Kára that of the third. It is always about the rebirth of the previous couple. Here, as elsewhere, it can be seen that the names are retained over much longer periods of time than motifs and incidents.

With such a highly complex development process, the question of age is already very problematic, since the concept of age presupposes a zero point that has to be set differently for each motif element.

One will therefore have to distinguish between a pre-Viking period, a Viking period and a medieval period. This periodization is overlaid by the influences of first pagan-Roman, then Roman-Christian culture. If one assumes, for example, that the runes go back to Roman influences, then this cannot be ignored in the myth of Odin as the one who acquired the secret of the runes.

Early critique of myths

After the ahistoricity of the myth was discovered very early, people began to think about how such “fables” came about. This type of saga criticism gave rise to a new type of myth.

Just as Euhemeros believed he could explain the myths of gods in Greece by the fact that the gods were kings of prehistoric times, who were later mythically deified, so Snorri Sturluson also made Odin an original king in Saxland in his Heimskringla . Thus the myth of the origin of the world became a myth of history, namely a myth of origin. It can no longer be determined whether Snorri learned of the explanation of the Euhemeros. It would be possible because the Icelandic sagas of antiquity were written during this period (end of the 12th to the middle of the 13th century), followed by the works De exidio Troiae Historia des Dares Phrygius , the Historia Regum Britanniae by Geoffrey of Monmouth , which were widely distributed in the Middle Ages and the Alexandreis of Walter von Châtillon and other traditions were based. An enlightening tendency was already noticeable at that time. B. Homer's Iliad was ignored as a fairy tale and the Dares Phrygius version was preferred instead.

Mythology under Christianity

In the past, the resounding success of Christianization was attributed to a weakness and the decline in the persuasiveness of mythology. The Danish church historian Jørgensen saw the victory of Christianity as rooted in the barbarism of the previous pagan faith. With Christianity culture came into the barbaric Nordic people. On the other hand, it can be stated for mythology that, in contrast to religious practice, it survived Christianization almost unscathed. This can already be seen in Snorri Sturluson. He saw clearly that Nordic poetry would cease without mythology. Because she was dependent on mythological paraphrases, the Kenningar . Hence, the mythology had to be known to both the writers and the listeners. It is for this reason that the Scandinavian churches did not fight mythology. On the old churches there are carvings with allusions to pagan mythology.

The pagan mythical beings in a Christian context

The many pagan beings suffered different fates in the Christian context, depending on how they could be integrated into Christianity. The same applies to ritual acts.

Mythical beings

Many pagan gods were reinterpreted under Christianity as devils or people with magic knowledge. The image of the Nordic heaven of gods contradicted the descriptions of the Christian Bible or the Heavenly Hierarchy and therefore could not be easily integrated into the medieval worldview. One can logically divide the perception of the mythical beings of pre-Christian paganism into two groups: One group was declared diabolical and opposed. The other was integrated into Christianity.

This integration can be clearly seen in the treatment of the Fylgja . They had an important function as a link between the living and the dead of one sex. Therefore one had to integrate them into the Christian cult in some way. Approaches to this can be seen in the Flateyjarbók and in the Gísla saga Súrssonar . In the Flateyjarbók the Þáttr Þiðranda ok Þórhalls is handed down. There it is described how the son of a large farmer leaves the house because he heard a knock on the door. In the morning he is found dying. He also reports that he was attacked in front of the door by nine women in black who were fighting against him. A little later, nine women dressed in white came to help him, but came too late. This dream is interpreted in such a way that the black women were the old pagan fylgjen of his sex, the white women the new Christian ones. But these could not have helped him because he was not a Christian. In the Gíslasaga, Gísli has two dream women. One is bad, but Gísli reports of the good one that she advised him, in the short time he still had to live, to give up the old faith and no longer deal with magic, but be good to the deaf, lame and Should be poor. A clear echo of the Christian guardian angel can be seen here. But in the sagas of the 13th century Fylgja is still Fylgja and no angel and is a pagan vestige side by side with Christian ideas. But the Christian Skald bjǫrn Arngeirsson hítdœlakappi († around 1024) writes in his Lausavisur verse 22 from a Dream shortly before his death that a helmet-armed woman wanted to bring him home. The helmet-armed woman in the dream is clearly recognizable as a Valkyrie . For the Christian, however, “home” was the kingdom of heaven. It is doubtful whether the stanza is real, i.e. whether it was composed by the skald in the 11th century. But if the poem was not written by the saga author until the 13th century, it is remarkable that a Valkyrie of Odin or Freya's could bring a Christian home 200–300 years after Christianization.

The division of mythical beings into beings accepted by Christianity and condemned by Christianity can probably also be seen in Snorris Gylfaginning . There he divides the originally mythical albums into black albums and white albums . However, there is no appreciation or depreciation associated with this division, but rather it describes areas of responsibility of these beings.

The idea of dwarfs lived on in Christianity, but not as mythical beings. They went into popular belief without further ado. Although they had a function in the pagan world of ideas, they did not pose a threat to the Christian faith. The ideas about the Norns and fate also lived on, but not without problems. Hallfrøðr vandræðaskáld (around 965 - around 1007) rejects Odin and the Norns in verse 10 of his Lausarvisur and considers them to be dazzling. However, the view of the Norns in Norway and Iceland was different. In Iceland, the Norn quickly became a witch . As an evil figure, she lived on in popular belief, but became harmless in a religious context. In Norway, the idea that the Norns determined fate lived on. In Borgund stave church there is a runic script with the text: “I rode past here on St. Olav's Day. The Norns did me a lot of harm when I rode by. "

Another problem are the jutes, which also include the Midgard serpent . They were the opponents of the gods who were demonized in Christianity. Most religious historians are of the opinion that the jutes were not worshiped and were thus cultically differentiated from the gods. But it is also believed that some jutes were also the subject of a cult. In any case, the jutes are sometimes referred to as "illi Óðinn" (the bad Odin), which in turn is a name for the devil. But one of the most important qualities of the Joten was their cleverness, so they didn't just get demonized. Rather, they were also partially “demythologized” into simple trolls in popular belief and superstition.

Serpents and dragons were not as related to the Midgard serpent as the Thor's hammer was to Thor . They had different symbolic content in the respective context. Their fate after Christianization also depended on it. Dragons and snakes also exist in Christianity and are equated with the devil. The serpent appears in the Bible as a seductress. In normal literature there are examples of snakes as a symbol of evil. When the bishop Guðmundur Arason wanted to enter the bay of Hjørungavåg, according to legend, a huge sea serpent blocked his way. He sprinkled them with holy water. The snake had to give way. The next day, the worm was found cut into twelve pieces on the beach. The dragon pierced with a sword symbolizes the victory of good over evil. The fact that Sigurðr fáfnisbani kills the dragon Fafnir in Fáfnismál - a widespread motif in Edda poetry - is indeed settled in the pagan period, but was not written until the 13th century and is a parallel motif to similar motifs from the Old Testament and pointing to Christianity and Sigurðr seen as forerunners of Christian heroes to whom similar things were ascribed. While the right portal column of the Hyllestad Church shows Sigurðr, the left column shows Samson strangling the lion.

But in Norse myths, the snake is not seen only negatively. The Midgard Serpent, which lies around the world, holds them together and thus prevents the world from falling apart into chaos. On the one hand, the dragon had an aggressive symbolic content. On the "stál", the top piece of the stern of a warship, sat the dragon's head. Judging by all source types, literary, archaeological and pictorial material, the dragon heads were relatively rare on the ships. After the Landnámabók it was forbidden to sail into the home port with the kite head on the stem. The country's guardian spirits could be raised or driven out. On patrols, he was supposed to drive out the enemy's guardian spirits. Whoever drove away the guardian spirits of the attacked country and subjugated the country was the new local ruler. Therefore, in the sources, the ships with dragon heads are regularly attributed to the leaders of the companies. The dragon, on the other hand, could be associated with protection. The dragon lies on top of the treasure or wraps around it. That is its guardian function. In research, dragon figures are often viewed as pure decoration, especially on stave churches, but also on pieces of jewelry and bracelets. But Mundal suspects that they have an apotropaic function. In churches they should keep the pagan out. While dragons adorned churches on the continent along with other grimaces, it is noticeable that the dragon heads are predominant in Norwegian stave churches, and even in reliquary shrines. This may be due to the fact that the dragons in profane art in pre-Christian times had a symbolic content that was known to everyone, which also made them wearable in church art. They can be interpreted as keeping evil away, but also as the omnipresence of evil, even within the church.

Cult acts

In the older Frostathingslov and Gulathingslov , blót to pagan powers, pagan burial mounds and altars is forbidden. Even in the later Christian rights of 1260, such as the more recent Gulathings Christian Law, and also in a sermon in the Hauksbók from the first third of the 14th century, the reprehensibility of believing in or worshiping the protective spirits of the country is mentioned. The custom is likely to have persisted for several hundred years. One reason for the long persistence of the customs for the country's guardian spirits may be that they were viewed as less dangerous to Christianity than belief in the gods.

The same goes for the ancestor cult. Christianity met him with suspicion. Thus, in Section 29 of the Senior Gulathingslov, it is forbidden to make sacrifices at the burial mounds. But the ancestor cult lived on under Christianity. This may be because ancestor worship is an important religious element in a clan society and Christianity saw in it the belief in life after death. And ancestor worship and ancestor worship were then separated from each other.

See also

- This

- Germanic mythology

- Anglo-Saxon mythology

- Continental Germanic mythology

- Germanic creation story

literature

- Detlev Ellmers : The archaeological sources for the Germanic religious history. In: Heinrich Beck, Detlev Ellmers, Kurt Schier (eds.) Germanic religious history. Sources and source problems. Berlin 1992 (supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Vol. 5). Pp. 95-117.

- Jacob Grimm: German Mythology . Marix Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86539-143-8 .

-

Vilhelm Grønbech : Before folkeæt i oldtiden , Vol. I – IV. [1909-1912] Copenhagen 1955. (German and German culture and religion of the Teutons , Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 1954, 2 vols.)

- 1. Lykkemand and Niding

- 2. Midgård and Menneskelivet

- 3. Hellighed and Helligdom

- 4. Menneskelivet og Guderne

- Knut Helle (Ed.): Aschehougs Norges Historie . Aschehoug, Oslo 1995

- 1. - Fra jeger til bonde - inntil 800 e Kristus , ISBN 82-03-22014-2

- 2. - Vikingstid ok rikssamling. 800–1130 , ISBN 82-03-22015-0

- Oddgeir Hoftun: Norrön tro og kult ifölge arkeologiske og skriftlige kilder , Solum Forlag, Oslo 2001, ISBN 82-560-1281-1

- Oddgeir Hoftun: Menneskers og makters egenart og samspill i norrön mytologi , Solum Forlag, Oslo 2004, ISBN 82-560-1451-2

- Oddgeir Hoftun: Kristningsprosens og herskermaktens ikonografi i nordisk middelalder , Solum Forlag, Oslo 2008, ISBN 978-82-560-1619-8

- Otto Höfler: The victim in the Semnonenhain and the Edda . In: Hermann Schneider (ed.): Edda, Skalden, Sagas. Festschrift for Felix Genzmer's 70th birthday . Winter, Heidelberg 1952, pp. 1-67

- Henrik Janson : 'Edda and "Oral Christianity": Apocryphal Leaves of the Early Medieval Storyworld of the North', in: The Performance of Christian and Pagan Storyworlds. Non-canonical Chapters of the History of Nordic Medieval Literature, L. Boje Mortensen och T. Lehtonen, (Turnhout: Brepols 2013), pp. 171–197. 2013, ISBN 978-2503542362 .

- Kris Kershaw: The One-Eyed God. Odin and the Indo-European male societies . 2004, ISBN 3-935581-38-6

- Jónas Kristjánsson: Eddas and Sagas. The medieval literature of Iceland , Buske, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-87548-012-0

- Henning Kure: “Geden, hjorten og Læráðr. Eller hvordan man freeze nordisk mythologi fra Snorris Edda. ”In: Jon gunnar Jørgensen (ed.): Snorres Edda i europeans and islands culture. Reykholt 2009. ISBN 978-9979-9649-4-0 . Pp. 91-105.

- Mirachandra: " Treasure of Norse Mythology I" - Encyclopedia of Norse Mythology from A – E. Mirapuri Publishing House. ISBN 978-3-922800-99-6

- Michael Müller-Wille: sacrificial cults of the Teutons and Slavs . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1999.

- Else Mundal: Midgardsormen and other heidne vesen i kristen Kontekst. In: Nordica Bergensia 14 (1997) pp. 20-38.

- Britt-Mari Näsström: Fornskandinavisk religion. En grundbok. Lund 2002a.

- Britt-Mari Näsström: Blot. Tro och offer i det förkristna north . Stockholm 2002b.

- Rudolf Simek : Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 368). 2nd, supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-520-36802-1 .

- Rudolf Simek: Religion and Mythology of the Teutons . Scientific Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-16910-7

- Klaus von See u. a .: Commentary on the songs of the Edda. Songs of the gods . Winter, Heidelberg

- Vol. 2. Skírnismál, Hárbarðslióð, Hymiskviða, Lokasenna, Þrymskviða , 1997, ISBN 3-8253-0534-1

- Vol. 3. Völundarkviða, Alvíssmál, Baldrs draumar, Rígsþula, Hyndlolióð, Grottasöngr , 2000, ISBN 3-8253-1136-8

- Vol. 4. Helgakviða Hundingsbana I, Helgakviða Hiörvarðssonar, Helgakviða Hundingsbana II , 2004, ISBN 3-8253-5007-X

- Preben Meulengracht Sørensen: Om eddadigtees alder. (About the age of the Edda poetry) In: Nordisk hedendom. Et symposium. Odense 1991.

- Manfred Stange (ed.): The Edda. Songs of gods, heroic songs and proverbs of the Germanic peoples. Complete text edition in the translation by Karl Simrock . Bechtermünz-Verlag, Augsburg 1995, ISBN 3-86047-107-4

- Preben Meulengracht Sørensen: Om eddadigtens alder (About the age of the Edda poetry). In: Nordisk hedendom. Et symposium. Odense 1991. pp. 217-228.

Web links

- Memories of Nordic mythology in the folk tales and superstitions of Mecklenburg, 1855

- Information on mythology ( memento of June 14, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) and everyday life of the Vikings

- Germanic mythology: texts, translations, scholarship

Individual evidence

- ↑ Näsström (2002b) p. 13.

- ↑ a b Sørensen p. 225.

- ↑ Ellmers p. 109 ff.

- ^ Translation by Gustav Neckel and Felix Niedner

- ^ A b translation by Gustav Neckel and Felix Niedner.

- ↑ Gylfaginning chap. 22, 23.

- ↑ Gylfaginning chap. 9.

- ↑ Kirsten Hastrup : Cosmology and Society in Medieval Iceland. A Social-Anthropological Perspective on World-View. In: Etnologia Scandinavia 1981. pp. 63-78.

- ↑ Jens Peter Schjødt: Horizontal and vertical axes in the pre-Christian Scandinavian cosmology . In: Old Norse and Finnish Religions and Cultic Place-Names. Åbo 1990. pp. 35-57.

- ↑ On the following: Kure 2009.

- ↑ From the Edda, Völuspá (The seer prophecy), translation by Karl Simrock: "The castle wall was broken by the sir, / battle-wise Wanen stamped the field. / Odin hurled the spit on the people: / There was murder first in the world." Translation by Felix Genzmer: "Odin threw the Ger into the enemy army: / the first war came into the world; / the ramparts of the Aesir castle broke, / Wanen stamped the corridor with boldness."

- ↑ Gylfaginning chap. 23

- ↑ Jens Peter Schjødt: Relations mellem Aser and vaner and ideological implications . In: Nordisk hedendom. Et symposium . Odense 1881. pp. 303-319.

- ↑ Ellmers p. 110.

- ↑ Horst Zettel: The image of the Normans and the Norman incursions in West Franconian, East Franconian and Anglo-Saxon sources from the 8th to 11th centuries . Munich 11977. pp. 148-152.

- ↑ by See pp. 115, 125, 609.

- ↑ Maurer II, 263.

- ^ AD Jørgensen: The nordiske kirkes grundlæggelse og første udvikling. Copenhagen 1874–1878.

- ↑ Steinsland p. 336.

- ↑ Mundal p. 23.

- ↑ Mundal p. 24. Mundal quotes here from Chapter 22 of the short version of the saga. In the version of the Isländersagas vol. 2. Frankfurt 2011. ISBN 978-3-10-007623-6 . S 142 f. this advice is expressed in a poem by Gísli, without an invitation to conversion.

- ↑ Mundal p. 24. The Lausavisur is available here from Norrön and Danish.

- ↑ Mundal p. 24. Gylfaginning chap. 17th

- ↑ Mundal p. 25. Lausavisur norrön and English.

- ↑ Mundal p. 25.

- ^ Erich Burger: Norwegian stave churches. History, construction, jewelry . First published, DuMont, Cologne 1978 (= DuMont-Kunst-Taschenbücher; 69), ISBN 3-7701-1080-3 .

- ↑ Mundal p. 26.

- ↑ Mundal p. 26. In the Flateyjabók there is the story “Óðinn kom til Ólafs konungs með dul ok prettum” (Odin comes to King Olaf (the saint) in disguise and with cunning). When the king recognized him, he drove him out by hitting his breviary on the head and called him "illi Óðinn".

- ↑ Guðmundar saga Arasonar , chap. 12 (norrøn text)

- ↑ Klaus von See u. a .: Commentary on the songs of the Edda. Hero songs. Vol. 5. Heidelberg 2006. p. 368.

- ^ Preben Meulengracht Sørensen: Thor's Fishing Expedition . In: Gro Steinsland (Ed.): Words and Objects: Towards a Dialogue between Archeology and History of Religion. Oslo 1986. pp. 257-278, 271-275.

- ↑ Mundal p. 31.

- ↑ Mundal p. 33.

- ↑ For example at the reliquary of the Heddal stave church .

- ↑ Mundal p. 36.

- ↑ Norges Gamle Lov I: Den Ældre Frostathingslov III, 15 ; Den Ældre Gulathings-Lov 29.

- ↑ Norges Gamle Lov II: Nyere Kristenrett 3.

- ↑ a b c Mundal p. 22.