Dragon (mythology)

A dragon ( Latin draco , ancient Greek δράκων drakōn, "snake"; actually: "the staring gazer" or "keen-eyed (it animal)"; the Greeks and Romans the name for any non-poisonous larger snake species) is a snake-like hybrid creature of mythology , in which properties of reptiles , birds and predators are combined in different variations. In most myths, it is scaled, has two hind legs, two front legs, two wings (so six limbs ) and a long tail. It is said to have the ability to spit fire . The dragon is known as a mythical creature from myths , sagas , legends and fairy tales of many cultures ; up to modern times it was regarded as a really existing animal.

In oriental and western creation myths , the dragon is a symbol of chaos , a god-hostile and misanthropic monster that holds back the fertile waters and threatens to devour the sun and moon. It must be overcome and killed by a hero or a deity in battle so that the world can arise or continue to exist (see Dragonslayer ). In contrast, the East Asian dragon is an ambivalent being with predominantly positive properties: rain and good luck charms and a symbol of fertility and imperial power.

Description of the dragon myth

Appearance and attributes

Tales and images of dragons are known in many cultures and epochs, and its manifestations are correspondingly diverse. Basically, it is a hybrid being made up of several real animals, but the multi-headed snakes of ancient mythologies are also called dragons. The snake proportions are predominant in most dragons. The body is mostly flaky . The head - or the heads, there are often three or seven - comes from a crocodile , a lion , a panther or a wolf . The feet are the paws of big cats or eagle claws . Usually the dragon has four; but there are also bipedal forms such as the wyvern and snake-like hybrids without feet. These are contrasted with the flying kites in typologies as crawling kites. The dragon's wings are reminiscent of birds of prey or bats . Common elements are a forked tongue, a sharp, penetrating gaze, the fiery throat and a poisonous breath. The demarcation to other mythical beings is not always clearly recognizable. Snake myths in particular have a lot in common with dragon tales , and the origins of the dragon from a cock's egg, as described in some tales, are borrowed from the basilisk . The Chinese dragon combines the characteristics of nine different animals: In addition to a snake neck , it has the head of a camel , the horns of a roebuck , the ears of a cow , the abdomen of a mussel , the scales of a fish , the claws of an eagle, the eyes the devil and the tiger's paws . The western dragon is usually of terrifying shape and size; as a symbol of the devil, ugliness determines his appearance. In its classic form it belongs to all four elements : it can fly, swim, crawl and spit fire.

iconography

The ancient dragon was above all a terrifying image and a symbol of power. The Roman army adopted the Draco standard as a standard from the Parthians or Dacians . The purple dragon flag was due to the emperor ; it was carried before him in battle and at celebrations. The Middle Ages continued this symbolism on flags , coats of arms , shields and helmets . The dragon still served Maximilian I as an imperial animal , and with the accession of the House of Tudor to the throne , the golden dragon found its way into the coat of arms of Wales .

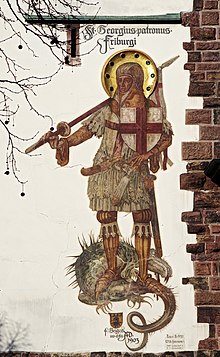

The independent image type of the winged, fire-breathing dragon, clearly differentiated from the snake, did not gain acceptance in Europe until the Carolingian era . In the fine arts and emblematic of the Christian Middle Ages he appears primarily as the embodiment of the devil or demon. But it also serves as a symbol of vigilance, logic, dialectics , cleverness and strength; There are also purely ornamental representations in building sculpture and illumination . From the High Middle Ages, the predominant motif of Christian dragon depictions is the fight against evil and original sin . Popular dragon slayers are Saint George and Archangel Michael , sometimes Christ himself appears as the victor over the beast. Sometimes the snake from paradise appears in the form of a dragon, the pictures of the Last Judgment show hell as a dragon's mouth. The demonic variant is the image of the dragon, which has now been adopted by fantasy culture.

Although there are different types in East Asia as well, the representation of the classic Chinese dragon Long is highly formalized. On ceremonial robes, its color and the number of claws indicated the rank of the wearer. The yellow dragon with five claws was reserved exclusively for the emperor himself. A special attribute of the Chinese dragon is a toy: a red ball belongs to the paper kite of the Chinese festivals in New York , and the dragon that chases a pearl has been common on ceramics since the Ming period . The meaning of the precious piece of jewelry is not clear. It could symbolize the moon or perfection.

Literary motifs

Of all the elements, the dragon is most commonly associated with water . The East Asian dragon brings the rain and guarantees the fertility of the fields, the ancient dragons are often sea monsters. The water-guarding monster appears in fairy tales and legends: It guards the only source or river that serves as a source of food and is responsible for floods and drought disasters. In fairy tales, the beast regularly demands human sacrifices . Rescuing the victim, preferably a virgin and king's daughter, ensures a kingdom for the victor. Earth dragons living in caves guard treasures. This motif , which has been known since ancient times, is possibly related to the belief in the dead. Even in folk tales of the 19th and 20th centuries, it is often the deceased who, in dragon form, secure their legacies from the access of the living. As a chthonic figure , the dragon also shows its connection to snakes . The dragon is the enlargement of the serpent into the grotesque and fantastic.

Dragon fight

The dragon fight is the most common literary topos associated with the dragon . Several types of narratives can be distinguished, for example according to the status of the hero or the setting (concrete or undefined). In antiquity, heroic combat predominated , with gods or mighty heroes appearing as dragons . The legendary Christian dragon fight, which mainly stems from biblical tradition, depicts the conflict between the saints and evil, with the dragon serving as an allegory . The decisive factor here is not physical strength or skill, but belief; often a prayer helps to victory. Other monsters such as huge wild boars can also take over the role of the dragon. Another type is the knightly-noble dragon slayer, who slays the dragon in a duel. Although these hero characters usually have strength, courage and high morale, they often have to resort to cunning due to the physical superiority of the dragon. In the bourgeois-peasant area of fairy tales and legends, the threatening beasts are often outwitted, poisoned or enchanted. Only the result counts here. The plague must be removed, the properties of the dragon slayer are secondary. Up to the present day the image of the dragon is used to represent the conflict between good and evil , to demonize the opponent and to make the victor appear as an overpowering hero.

Dragon Lair

A dragon lair is a collection of treasures in the care of a mostly fire-breathing dragon. Such hoards can be found in fairy tales , legends , stories , sagas and in modern fantasy literature, such as in the novel The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien . Most of the time, the dragon's lair is located in a cave in which it is guarded suspiciously by the dragon. In some legends, a dragon slayer sets out to slay the guardian and take the treasure. Some of these treasures are laden with curses and bring misfortune to the hero: for example the Nibelungen inheritance in the Old Norse Edda , which transforms the patricide Fafnir into a lindworm. In the Völsunga saga , it is a pot of gold that is in an otter's skin , which has to be set up and additionally covered with gold until nothing of the otter is visible anymore. In such a hoard in the Beowulf there are gold dishes, banners, helmets and rings.

Spread of dragon myths

The indologist Michael Witzel sees the story of the slaying of the dragon by a hero with superhuman strength as a basic element of what he called laura Malaysian storyline to: first mother and father produced in many mythologies a generation of monsters (Titans, giants, dragons, night creatures etc.) that must be killed in order to make the earth habitable. Often the blood of the dragon first makes the earth fertile or it waters it. This notion is also common in regions like Polynesia and Hawaii , where there are no large reptiles at all. This points to the spread of the myth through migration.

Plot elements and motifs that deal with dragons can be seen in the folklore of many other ethnic groups (see below). Due to the frequency of recurring motifs (e.g. "The dragon lives in or by the water" or "There is a fight with the dragon") the Finnish School assumes a common origin. On the basis of 69 motifs from 23 different ethnic groups, a phylogenetic reconstruction (a method from evolutionary biology to determine ancestry and relationships ) was carried out. Accordingly, the worldwide mythology about the dragon has its origin in southern Africa .

Classic kites

Middle East

The oldest Sumerian representations of dragons can be found on cylinder seals from the Uruk period . They belong to the hybrid creatures that are represented in a large number in the repertoire of images of the ancient Orient . The oldest written mention of a dragon can be found in the Keš temple hymn from around 2600 BC. Two basic types of kite can be identified: snake kites (end of the 4th millennium BC), which at least in part resemble a snake, and lion kites , which are mostly composed of elements from lions and birds (beginning of the 3rd millennium B.C.). Like all hybrid beings, the ancient oriental dragons are neither gods nor demons, but belong to their own class of supernatural beings, whose names and shapes indicate a connection with the animal kingdom or with the forces of nature. They are not clearly negative. There are exceptions, such as the hostile many-headed snakes, which come from the early dynastic period . As a rule, the early dragons appear in text and images as powerful, sometimes dangerous, but sometimes also protective beings.

The dragons are initially in loose connection with certain deities. In the Akkad period , however, they are added to the gods as servants, sometimes they are rebels and defeated opponents. On seals from around 2500 BC The motif of the dragon fight appears, but it is only passed down centuries later in mythological stories. In Mesopotamian texts of the late 3rd millennium, local gods initially appear as dragon slayers . The traditions are united around 2100 BC. In the Anzu myth: The warrior god Ninurta from Nippur triumphs over the lion eagle Anzu , who stole the plates of fate, and subsequently replaces Enlil as the supreme god of the Sumerian-Akkadian pantheon. The Ninurta mythology spread throughout the Middle East in the 1st millennium with the rise of the Assyrian Empire ; as Nimrod he found its way into the biblical tradition. While the Anzu myth is about the generation change in the hierarchy of gods, a second oriental type describes the struggle of the weather god with the elemental force of the sea, symbolized by the horned sea snake. This motif can be found in the Hittite Illuyanka myth, which dates from around 1700 BC. BC, in which around 1600 BC BC written down. Ugaritic Baal cycle and in the battle of Marduk , the Babylonian chief god, against sea deity Tiamat . In the wake of the Tiamat are wild serpent kites (ušumgallē nadrūti) , the serpent Basmu and the dragon Mušḫušḫu . The multi-faceted ancient oriental myths created an image of the dragon that is still visible today because they were incorporated into the texts of the Old Testament . The dragon of the Christian tradition has its origin in the ancient Near East.

India, Iran, Armenia

Even Indra kills a three-headed reptile which is represented as a dragon or serpent rain, and robbing its treasures. The name of the dragon, Vritra , recalls the Iranian warrior god Verethragna (dragon slayer), ousted by Indra , who sometimes represents and sometimes fights evil and was often equated by the Greeks with Heracles . In Armenia this corresponds to the figure of Vahagn , a god of light and thunder. The affinity of the names refers to the commonalities of the Indo-European ideas about the fight against a dragon that darkens the sun.

Bible

The Hebrew Bible uses the word tannîn for land snakes and serpentine sea dragons. She also knows two individual, particularly dangerous snake dragons, Leviathan and Rahab . Both come from the sea, and in both of them the Middle Eastern narrative tradition lives on. Leviathan is related to Litanu , Baal's adversary , the name Rahab probably has Mesopotamian roots. The Egyptian Pharaoh as the enemy of God is also compared to a dragon (tannîn) :

"You are like a lion among the heathen and like a sea dragon, and you leap in your streams and stir the water with your feet and make its streams cloudy."

The biblical dragon myth not only reproduces the ancient oriental models, it develops them further. The kite fight is no longer just an act of the beginning, but also becomes an act of the end. The book of Daniel already describes visions of eschatological lion dragons, and the Revelation of John makes the Archangel Michael fight the great, fiery red, seven-headed serpent dragon. Michael wins in the sky fight, and

In the images of the St. John Apocalypse, the dragon finally becomes the personified evil who is responsible for all violence after his fall from heaven. Its destruction coincides with the end of the world.

Greek and Roman antiquity

With the Greek dragons the snake aspect predominates, so that it is not possible to differentiate with all mentions whether the talk is of the mythical creature or a snake. The monsters of Greek mythology come from the sea or live in caves. They are often multi-headed, huge and ugly, have keen eyes and fiery breath, but rarely have wings. Well-known Greek dragons are the hundred-headed typhon , the nine-headed hydra , the snake god Ophioneus and python , guardian of the oracle of Delphi . Ladon guards the golden apples of the Hesperides , and the motif of the guard also appears in the Argonauts legend. In this version of the myth, there is no need to kill the beast in battle. Before Jason steals the Golden Fleece , the dragon is put to sleep by Medea . The constellation of dragon, hero and the beautiful princess, who is to be sacrificed to the monster, comes from the Greek legend. The rescue Andromeda before the sea monster Ketos by Perseus is since ancient times a popular motif in art.

Antiquity has enriched the image of the dragon in subsequent epochs with a number of facets. Europe adopted the word "dragon" from the Greeks and Romans. The Greek "drákōn" ("the staring gazer", to Greek "dérkomai" "I see") has found its way into the European languages as a loan word from the Latin "draco": as "trahho" for example in Old High German , as "dragon "In English and French, as" drake "in Swedish. The name of the constellation of the same name goes back to Greek astronomy , and the European dragon symbolism also shows ancient influence. The Dracostandarte , originally a Dacian or Sarmatian standard, was adopted by the Germanic and Slavic tribes from the Roman army during the migration period. The terrifying monster is not an enemy here, but a symbol of one's own strength that is intended to intimidate the opponent.

Christian Middle Ages

The Christian Middle Ages maintain the strong bond between dragons and devils. In pictures of exorcisms , the devils in the form of small dragons come out of the possessed's mouth, demons in dragon form adorn baptismal fonts and gargoyles of Gothic cathedrals . The legends of the saints take over the allegorical imagery of the Bible . The dragon has around 30 opponents in the Legenda aurea alone , a total of around 60 dragon saints are known. The monster stands for the torments of the martyrs in the acts of martyrdom , in the vites of the early medieval messengers of faith the dragon personifies paganism, sin, and later heresy. He is not always killed in battle. The victory over him is a miracle carried out with God's help, the sign of the cross or a prayer is enough to scare him away. In the High Middle Ages, three dragon saints ranked among the fourteen helpers in need : Margaret of Antioch , who fought off the dragon with the sign of the cross, Cyriacus , who cast out the devil of an emperor's daughter, and George . He becomes the most popular of all the sacred dragon slayers; his lance fight against the beast is spread around the world in countless representations to this day. The coats of arms of German cities, which show the dragon as a common figure , are mainly derived from the legend of St. George, and many folk customs and dragon festivals can be traced back to them. For example, the Further Drachenstich and in Belgium the Ducasse de Mons are known . The Catalan fire race Correfoc is a spectacular festival , when fire-breathing dragons and devils roam the streets. The festival may have pre-Christian origins, but has been associated with the Catalan patron saint St. George since the Middle Ages. In Metz , on the other hand, according to legend, it was Bishop Clemens who drove away the dragon Graoully , who lived in the amphitheater , and led it out of the city on his stole . Until the 19th century, a representation of the dragon was carried through the streets and beaten by the children of the city.

The dragon occupies a prominent position in the ornamental art of the Viking Age . Dragon heads decorate rune stones , fibulae , weapons and churches. "Dreki" is a common name for ship types in the Viking Age; However, contrary to modern adaptations, the dragon has not been archaeologically proven as a pictorial motif on the bow. The dragon is well documented in Germanic literature from the 8th century to modern times, especially in heroic poetry , and occasionally in the Norse skalds . The old English epic Beowulf mentions crawling or flying dragons, which among other things act as guardians of treasures. In old Scandinavian sources, they protect against hostile spirits. The Germanic word lindworm is a pleonasm : Both the old Icelandic linnr and the worm denote a snake, and the descriptions of the lindworms are more like snakes than kites. The Teutons later not only adopted the name, but also the idea of the flying monster. The lint dragon of the Nibelungenlied shows the fusion of both beliefs. Medieval Germanic sources also incorporate ideas from Norse mythology , such as the Midgard serpent or Fafnir , a greedy patricide in the form of a dragon, whose fate is reported in the Edda and the Völsunga saga . The envy dragon Nidhöggr , which gnaws at the world ash, is more likely to be traced back to Christian visionary literature . The individual relationships between non-Christian and Christian inheritance are uncertain.

In the High Middle Ages the dragon became a popular opponent of knights in the heroic epic and in the courtly novel . In the Arthurian tradition , but especially in the legends around Dietrich von Bern , a dragon fight is almost an obligatory part of a heroic résumé. With the victory, the hero saves a virgin or an entire country, acquires a treasure or simply shows his courage. The special characteristics of the loser are often passed on to the winner: Bathing in the dragon's blood makes Siegfried invulnerable, so other heroes eat the dragon's heart.

Early science

A synthesis of ancient and Christian traditions can be observed in the views of medieval scholars on the dragon. Already Pliny the Elder wrote parts of the dragon body, a medical effect to, Solinus , Isidore , Cassiodorus and others arranged the beast in the animal kingdom one. The medieval naturalists were, in view of the abundance of biblical references, even more convinced of the real existence of the beasts. "With the exception of its fat, none of its flesh and bones can be used for healing purposes," wrote Hildegard von Bingen in her theory of nature. It was believed of dragons that they could arise from the bodies of slain people on battlefields, similar to how maggots “arise” from animal carcasses.

The early modern researchers set up detailed systematics of the various dragon species: Conrad Gessner in his snake book from 1587, Athanasius Kircher in Mundus Subterraneus from 1665 or Ulisse Aldrovandi in the work "Serpentum et Draconum historia" from 1640. Dragons remained until well into modern times a part of living nature, for whose existence there was apparently evidence. For early scientific collections and natural history cabinets, the scholars acquired found objects from distant countries, which were composed of dried rays , crocodiles, bats and lizards - in today's sense fakes, in the understanding of the early modern scholarly culture "reconstructions", which merely the discovery of a "real" dragon anticipating. Still Zedler's Universal-Lexikon said, was the dragon:

“[…] An enormous snake that tends to stay in remote desert oes, mountains and rock crevices, and which causes great harm to people and cattle. There are many forms and kinds of them; for some are winged and some are not; some have two feet, others four, but Kopff and Schwantz are snake-like. "

It was not until the modern natural sciences in the 17th century that most of these ideas were rejected, but there were also critical voices early on. Bernhard von Clairvaux already refused to believe in dragons, and Albertus Magnus took the reports of flying, fire-breathing creatures for observations of comets. The Alchemy used only as the dragon Symbol: Ouroboros , biting its own tail and gradually eats itself, standing for the Prima materia , the starting material for the preparation of the stone of ways . Modern zoology excluded the dragon from its systematics since Carl von Linné , but outside of the strictly scientific discourse he remained far more persistently "real" than many other mythological beings. The hunt for dinosaur dragons ( see below ) was a serious business at the beginning of the 20th century.

Fairy tales and legends

The dragon is one of the most common motifs in European fairy tales . In what is probably the most common type of dragon tale, the “dragon slayer” ( AaTh 300 ), the monster appears as a supernatural opponent. A simple man often opposes him as a hero : the victor over the beast can be a tailor, a stargazer or a thief. Correspondingly, victory cannot always be won by force of arms, but requires cunning or magic. Well-meaning animals or clever people appear as helpers. The fairy tale is closely related to the myth and the heroic saga, which is particularly evident in the dragon tales. The motifs match down to the last detail: Often a virgin has to be saved, a treasure won or the dragon's tongue cut out so that the hero receives proof that he himself and not a rival killed the monster.

In addition to the dragon slayer, there are a number of other fairy tale types in which the dragon plays a role. The story of the animal consort is widespread : Here the hero is transformed into an animal, often a dragon. The bride must break the spell and redeem the hero with love and steadfastness. The mixing of dragons and humans is more common in Eastern European fairy tales. The Slavic dragon is sometimes a half-human hero who can ride and fights with knightly weapons, and who can only be recognized as a dragon by his wings.

There are two types of dragon sagas. On the one hand there are etiological narratives that describe how a place got its name; These include the story of Tarasque , to which the southern French city of Tarascon derives its name, or the legend of the Wawel dragon , after which the Wawel hill in Krakow is named. The second type are explanatory legends that ascribe special natural phenomena (for example “footprints” in the rock) to the action of dragons. In the area of the legend, the "eyewitness reports" are located, which, for example, made the alpine Tatzelwurm famous - the chroniclers of the Renaissance still considered the alpine dragon, which many alpine inhabitants wanted to meet, to be a real animal. The European dragon sagas are generally more realistic than the fairy tale. The place and time of the event are always indicated: The local dragon stories preserve the residents' pride in being something “special”. And there is not always a happy ending . Defeating the dragon can also cost the hero their lives.

East asia

The oldest East Asian depictions of dragon-like hybrid creatures come from the Chinese region. The Neolithic cultures on the Yellow River left objects made of shells and jade that snakes combine with pigs and other animals. From the Shang Dynasty (15th to 11th centuries BC), the dragon symbolized royal power, and the Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) established its shape. The Chinese dragon Long is the most important origin of Far Eastern dragon ideas: Since the Song dynasty (10th century), Buddhism took over the hybrid being and spread it throughout the entire East Asian region.

The Chinese dragon (after Michael Witzel only recently) has a more positive meaning than its western counterpart. It stands for spring, water and rain. Since it combines the characteristics of nine different animals in itself, it is assigned to the yang , the active principle, according to Chinese number mysticism . It also represents one of the five traditional types of living beings, the pangolins, and in the Chinese zodiac it is the fifth among twelve animals. Together with the phoenix ( fenghuang ) , the turtle (gui) and the unicorn ( qilin ), the Chinese dragon is one of the mythical "four miracle animals " ( siling ) that helped the Chinese creator of the world, Pangu .

The dragon of Chinese folk tales has magical abilities and is extremely durable: it can take thousands of years to reach its final size. As an emperor it has five claws and is yellow in color, otherwise it only has four claws, as for example in the flag of Bhutan . The duo dragon and phoenix have represented the emperor and empress since the time of the warring states . The imperious and protective dragon of mythology is also opposed to the ominous dragon of Chinese folk tales. The dragon in China is not a consistently positive, but an ambivalent being.

The dragon plays a major role in Chinese art and culture: There are sculptures made of granite , wood or jade , ink drawings, lacquer work, embroidery, porcelain and ceramic figures. Dragon myths and rituals are already written in the I Ching book from the 11th century BC. Traditionally, the spring and autumn annals depict dragon ceremonies intended to summon rain. The Dragon Boat Festival in its current form dates back to the pre-Han period, and dragon dances and processions are also part of the Chinese New Year and Lantern Festival . The Feng Shui considers the Dragons while building houses, garden design and landscape design, and the Chinese medicine knows recipes from dragon bones, dragon -zähnen or saliva; The starting materials for this are, for example, fossils or reptile skins .

The Thai Mangkon , the dragons in Tibet , Vietnam , Korea , Bhutan or Japan have Chinese roots that have mixed with local traditions. Some elements of Far Eastern dragon cults also show parallels with the Nagas , the snake deities of Indian mythology . For example, the dragons from Japanese and Korean myths often have the ability to metamorphose : they can transform themselves into people, and people can be reborn as dragons. The respect for the rulers over the water meant that the Tennō claimed descent from the dragon king Ryūjin . Likewise, the Korean kings traced their ancestry back to dragon deities. A particularly strong local tradition has shaped the image of the dragon in Indonesia : in contrast to China, the mythical creature here is female and protects the fields from mice at harvest time. Dragon pictures are hung over children's cradles in order to ensure a peaceful sleep for the children.

America

Hybrid creatures with snake parts are not alien to the mythologies of South, Central and North America. The best known is the amphithere or feathered serpent, a form that, for example, the Mesoamerican god Quetzalcoatl takes, but there are other types. The double-headed snake is common in North and South America; besides the two heads - one at each end - it sometimes also has a third, human head in the middle. Chile knew the fox snake "guruvilu", the Andean inhabitants "amaro", a mixture of a snake and a cat-like predator. Rain god Tlaloc could take the form of a hybrid of snake and jaguar, and the fire element is also represented in the serpent cult of America: the fire snake Xiuhcoatl was responsible for drought and poor harvests among the Aztecs . Detailed investigations were particularly dedicated to the gods and mythical creatures of the Olmecs . A hybrid creature with proportions of caiman, hedgehog, jaguar, human and snake can be found in large numbers on stone monuments and ceramics, which were found in San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan , Las Bocas and Tlapacoya , for example . A classification of this being in a mythological context is impossible because there are no written documents. The American and East Asian kite depictions show many similarities. The dragon motif therefore also served as an argumentation aid for attempts to find transpacific relations between China and pre-Columbian America. However, there is currently no generally accepted evidence for this thesis.

Islam

Arabic dictionaries refer to the dragon as tinnīn (تنين) or ṯuʿbān (ثعبان), the common Persian name is Aždahā (اژدها). He is generally land dweller, often cave dweller, and, like the western dragon, embodies evil. The images of dragons in Islamic culture combine western and eastern elements into an independent style. Pre-Islamic-Persian, Indian, Greek, Jewish and Chinese influence can be felt in them.

In the medieval Arab world, the dragon is a common astronomical and astrological symbol. In the form of a snake he already appears in the Kitāb Suwar al-Kawākib ath-Thābita ("Book of the Shape of Fixed Stars ", around 1000 AD), where Abd ar-Rahman as-Sufi illustrates the constellation of the same name . The idea of a giant dragon lying in the sky, where its head and tail form the upper and lower nodes of the moon, goes back to the Indian Nagas . The sky dragon was blamed for solar and lunar eclipses as well as comets.

Despite the predominantly "western" orientation towards the ominous dragon type, Islamic images have shown unmistakable Chinese influence since the Mongolian expansion in the 13th century. Decorating sword hilts, book covers, carpets, and china, the dragon is a long, wavy creature with antennae and whiskers. Miniatures in manuscripts from the 14th to 17th centuries from Persia, Turkey and the Mughal Empire provide numerous examples of this type.

In Islamic literature, the traditional dragon fight predominates. Shāhnāme , the book of kings, which was written around the year 1000, has passed down many dragon stories . Mythical heroes and historical personalities appear as dragon slayers: the legendary hero Rostam , Great King Bahram Gur or Alexander the Great . One of the main characters of the Shahnameh is the mythical dragon king Zahhak or Dhohhak , who is defeated by the hero Firaidun after a thousand years of reign. The Persian stories are rooted in myths from the Veda and Avesta periods , but have a strong historical component. They refer to the struggle against foreign rule and contemporary religious conflicts. A completely different type of dragon can be found in the Qisas al-Anbiyāʾ ("Prophet Tales"). The prophet is Moses ; the beast is his staff. If the staff is thrown on the ground, it turns into a dragon and helps the prophet in the fight against all kinds of opponents. In the qisas, the monster is a terrifying helper on the right side.

Dragons in the modern age

Dragons and dinosaurs

When the new science of paleontology discovered the dinosaurs at the beginning of the 19th century , the dragon myth received a new facet. Christians explained the fossil finds as the remains of antediluvian animals that would not have found a place on the ark . But the actual existence of the giant monsters the Bible speaks of also seemed to be proven. The book of the great sea Dragons was published in 1840 . Its author, the fossil collector Thomas Hawkins, equated the biblical sea dragons with the Ichthyosaurus and the Plesiosaurus ; He found the model for the winged dragon in the pterodactyl . But if the dinosaurs survived long enough to find their way into mythical tales as dragons, then they could still exist in the present, so the logical conclusion. The search for recent giant lizards became serious business in the 19th and early 20th centuries, fueled not least by the great success of Arthur Conan Doyle's novel The Lost World from 1912. Carl Hagenbeck had a giant animal searched for in Rhodesia as "half elephant, half dragon", and which he believed to be identified as a Brontosaurus .

So while paleontology helped to consolidate the belief in kites and transfer it to modern times, the old myth also worked in the opposite direction. The early models and illustrations of the dinosaurs, above all the popular representations by the Briton Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins , were just as dependent on interpretations of the finds as they are today, and the traditional idea of the dragon was incorporated into these interpretations. For his reconstruction of a pterosaur, Hawkins is said to have selected the Pterodactylus giganteus , excavated in 1847 , which, with a wingspan of 4.90 meters, came close to the idea of a dragon. The then better known pterodactylus , already described by Georges Cuvier , was hardly bigger than a sparrow.

In the City Museum Jena is in the context of the Seven Wonders a draco issued.

Fantasy culture

The dragon figure is experiencing a renaissance in fantasy culture. JRR Tolkien used the traditional motif of the treasure keeper for his Smaug , and in newer fantasy novels and role-playing games , comics , films and musicals , the authors borrow from fairy tales, heroic epics and folk ballads. However, the traditional meaning of the dragon is often broken up. Fantasy dragons are not consistently "good" or "bad". In some role-playing games - for example, Dungeons and Dragons - dragons occupy both sides. In others - like Gothic II , Bethesdas Skyrim or Guild Wars 2 - you have to kill the dragons to save the world or to avert disaster. In Anne McCaffrey's science fiction novels, they even fight alongside people against common enemies. Dragons in fantasy culture usually have properties such as lizard-like resemblance, flight ability, fire breath or similar abilities, size, intelligence and magical talent. Basically they are related to something magical, a task or a story, and often they have wisdom . The dark aesthetic of the fantasy images also contains an element of fascination: fantasy dragons are at the same time terrible and beautiful, noble and terrifying. It is noticeable that in most games the dragon can be fought or found, but rarely, as in Spyro , is played by yourself. The "friendly dragon" appears as a more recent element of the traditional possible meanings of the dragon. Dragons are used as a stylistic device to represent the good core in evil or outwardly mighty; Examples of this are Eragon , Dragonheart or How to Train Your Dragon .

Children's literature and cartoon series

The dragon symbol in modern children's books is finally turned into its opposite: Here the dragon is a cute, friendly and tame creature. The British writer Kenneth Grahame made the start with his work The Dragon Who Didn't Want to Fight from 1898, an anti-war book that wanted to break up old enemy images and counteract the positive attitude towards war and violence. In German-language children's literature, the figure only became popular after the Second World War . Michael Ende was one of the pioneers of the dragon wave : In his Jim Knopf series from 1960 to 1962, the helpful half-dragon Nepomuk still appears next to smelly, loud "real" dragons.

Countless dragon books and cartoons appeared from the 1970s. The initially degenerate Viennese dragons Martin and Georg appear surreal in Helmut Zenker 's children 's novels about the dragon Martin. Also known are Max Kruse's half-dinosaur Urmel from the ice , Peter Maffay's green Tabaluga , the kites of the Austrian Franz Sales Sklenitzka or the little Grisu , who actually wants to be a firefighter but sometimes unintentionally sets his surroundings on fire. “The little learning dragons” are the namesake of a series of learning books from Ernst Klett Verlag . The stories from the series “The Little Dragon Coconut” by Ingo Siegner are also widely distributed . The mythical creatures in children's books no longer have any negative properties; they are lovely through and through and won't harm a fly except by mistake. There is also criticism of defusing the old horror images. The old symbol of the devil would be robbed of its function of helping to overcome evil in reality.

Modern symbolism and advertising

The symbolic power of the dragon is unbroken in the present, despite the variety of types and nuances of meaning that have emerged in the millennia of development of the myth. As a mythical creature with a high recognition value , known almost worldwide , it is used as a trademark in the advertising industry . Some cities, countries and football clubs use the dragon as a heraldic animal , and some associations, clubs and institutions as a badge . Of the traditional meanings, the element of power and strength is decisive in the modern context . A red dragon on products from Wales advertises pride in the old national symbol, and the dragon is a universally understandable metaphor for the power of China .

The dragon has largely lost its malevolence in the western industrialized countries. The change in meaning can be explained on the one hand by the influence of fantasy culture and children's literature. The dragon logo of a cough drop, for example, shows a cute, colorful little animal smiling and offering a fruit. On the other hand, there are specific requirements to be met in global marketing . Advertising campaigns that feature evil dragons are not enforceable on a global scale. In 2004, for example, the sporting goods manufacturer Nike had to cancel a campaign in China in which basketball star LeBron James appeared as a dragon fighter. The victory over China's national symbol was seen as a provocation there.

Explanations

Natural historical origin hypotheses

A number of theories attempt to trace the origin of the dragon figure back to real natural phenomena. Although this was rejected early on in serious research, the question of whether and under what circumstances a memory of living dinosaurs could have arisen in humans is still discussed in pseudo and popular scientific presentations . Today's animal species such as the Indonesian Komodo dragon or the similarly South Asian species of the common kite and the frilled lizard are discussed as the origin of the dragon myth, and cryptozoology - although not scientifically recognized - pursues the search for other, as yet undiscovered animal species that are said to have served as models .

Another hypothesis assumes that the dragon myth can be traced back to fossil finds. It is true that skeletal remains of prehistoric animals found in caves, such as cave bears and woolly rhinos , have been shown to have influenced individual dragon sagas, but the fossil record itself cannot explain the myth itself.

Modern science no longer deals with dragons as possible living beings within the biological system .

Mythological interpretation

In the cosmogonic myths of Europe and the Middle East, the idea of the dragon predominates as a symbol of chaos, darkness and the forces that are hostile to human beings. The myth research of the 19th century therefore put the dragon in close connection with the moon; the “annihilation” and reappearance of the moon are reflected in the dragon myth, according to the Indologist Ernst Siecke . The interpretation of the dragon as a symbol for the conflict of natural forces, the change of the seasons and the victory of summer over winter is also one of the "lunar" attempts at explanation of early mythological research. In the 20th century, a newer generation of researchers, represented for example by the French Georges Dumézil , the Dutch Jan de Vries and the Romanian Mircea Eliade , recognized a parallel to the initiation rites in the dragon fight . In this explanation the fight is equated with the initiation test: Just as the hero has to defeat the dragon, the initiate has to pass a test in order to be able to enter a new stage of his life cycle. The encounter with a threatening being, a ritual devouring and a subsequent "rebirth" are frequent components of initiation rituals. De Vries also saw an echo of the act of creation in the dragon fight . Just like initiation, the fight with the beast is an imitation of the events of creation. It is the fight that most clearly distinguishes the dragon from the mythical snake. In contrast to her, the hybrid being combines the most dangerous characteristics of different animals and misanthropic elements. The dragon becomes the perfect opponent.

Calvert Watkins describes the dragon fight as part of an "Indo-European poetics".

The concept of dragons in East Asia was possibly linked to totemism in a very early period , with the dragon being said to be a compound of various totem animals. In the Far East he became a symbol of imperial rule on the one hand, and a water deity on the other. Ceremonies in which dragons are begged for rain show him as a rain god; like the ox, the dragon is related to a fertility cult . The connection with water is common to all dragon myths. Rüdiger Vossen presents a synthesis of “western” and “eastern” ideas: In his opinion, the ideal images “taming the water, asking for sufficient rain and fertility for fields and people” are links in the dragon myths of different cultures.

Psychoanalytic Interpretation

In the analytical psychology founded by Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961), the dragon is considered to be an expression of the negative aspect of the so-called mother archetype . It symbolizes the aspect of the destructive and devouring mother. As far as the dragon has to be killed in order to win the hand of a princess, it is also interpreted as a form of the shadow archetype that holds captive the anima personified in the princess . The shadow archetype stands for the negative, socially undesirable and therefore suppressed traits of the personality, for that part of the “I” that is pushed off into the unconscious because of anti-social tendencies. The anima, for Jung the “archetype of life” par excellence, is a quality in the man's unconscious, a “feminine side” in his psychic apparatus. According to this view, the kite fight symbolizes the conflict between two parts of the man's personality.

Other depth psychological and psychoanalytic interpretations see the dragon as an embodiment of the hostile forces that prevent the self from its liberation; an image of the overpowering father, a symbol of power and domination and a sanction figure of taboos . From a psychological point of view, the dragon fight is a symbol for the fight with evil inside and outside of oneself.

See also

literature

- Entry: dragon. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 3, Artemis, Munich / Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-7608-8903-4 , column 1339-1346 (various authors).

- Ulyssis Aldrovandi : Serpentum, et draconum historiae libri duo. Ferronio, Bologna 1640 (Italian).

- Ditte Bandini , Giovanni Bandini: The Dragon Book. Symbols - myths - manifestations. Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-023-4 (ethnological-popular science presentation of dragon myths from antiquity to modern times).

- Wilhelm Bölsche : Dragons. Saga and science. A popular representation. Kosmos, Society of Friends of Nature, Stuttgart 1929.

- Sheila R. Canby: Dragons. In: John Cherry (Ed.): Mythical Animals. About dragons, unicorns and other mythical beings. Reclam, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-15-010429-7 , pp. 19-67 (treatise on dragon motifs in art and literature).

- Sigrid Früh (Ed.): Fairy tale of the dragon Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-596-11380-6 (collection of dragon tales from France, Ireland, Scotland, Denmark, Germany, Serbia, Transylvania, Russia and Switzerland, with afterword by the editor).

- Joachim Gierlichs: dragon, phoenix, double-headed eagle. Mythical creatures in Islamic art (= picture booklet of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Prussian cultural property. Booklet 75–76). Mann Brothers, Berlin 1993.

- Zeev Gourarian, Philippe Hoch, Patrick Absalon (eds.): Dragons. In the zoological garden of mythology. Editions serpenoise, Metz 2005, ISBN 2-87692-674-1 (book accompanying the exhibition Dragons of the Conseil general de la Moselle and the Museum national d'histoire naturelle, in Malbrouck Castle, April 16 to October 31, 2005, and in National Museum of Natural History Paris 2006).

- Wolfgang Hierse: Cutting out the dragon's tongue and the novel by Tristan. Tübingen 1969 (doctoral thesis).

- Claude Lecouteux: The Dragon. In: Journal for German Antiquity and German Literature 116 (1987), pp. 13–31.

- Balaji Mundkur: The Cult of the Serpent. An Interdisciplinary Survey of Its Manifestations and Origins. Suny, New York 1983 (English).

- Reinhold Merkelbach : Dragon. In: Theodor Klauser (Ed.): Reallexikon für antike und Christianentum . Volume 4. Anton Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1959, pp. 226-250.

- Lutz Röhrich : dragon, dragon fight, dragon slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales . Volume 3, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-008201-2 , pp. 788-820.

- Bernd Schmelz, Rüdiger Vossen (ed.): On dragon tracks. A book on the kite project of the Hamburg Museum of Ethnology. Holos, Bonn 1995, ISBN 3-86097-453-X .

- Hans Schöpf: mythical animals. Academic printing and Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1988, ISBN 3-201-01436-2 (historical representation with a focus on legend, fairy tales and popular belief).

- Jacqueline Simpson: Fifty British Dragon Tales. Analysis. In: Folklore. Vol. 89, No. 1, 1978, pp. 79-93 (English).

- Jacqueline Simpson: British Dragons. Folklore Society, 2001, ISBN 1-84022-507-6 (English; first published 1980).

- Cornelius Steckner: Fantastic evidence or fantastic living space? Mythical creatures in early modern natural history cabinets and museums. In: Hans-Konrad Schmutz: Fantastic living spaces, phantoms and phantasms. Basilisken, Marburg an der Lahn 1997, ISBN 3-925347-45-3 , pp. 33-76.

- Sandra Unerman: Dragons in Twentieth-Century Fiction. In: Folklore. Volume 113, No. 1, 2002, pp. 94-101 (English).

- Elizabeth Douglas Van Buren : The Dragon in Ancient Mesopotamia. In: Orientalia. Volume 15, 1946, pp. 1-45 (English).

- Marinus Willem de Visser: The dragon in China and Japan. Müller, Amsterdam 1913 (English; online at archive.org).

Web links

- Liselotte Stauch: Dragon. In: RDK laboratory. Central Institute for Art History , 1955, accessed June 26, 2020 .

- Ruth Omphalius: Where do the dragons come from ? In: Monsters and Myths. Terra X , November 18, 2018, accessed June 26, 2020 .

- Bernhard Scheid: Animal Gods and Messengers of Gods, Part 1 - Imaginary Animals: Dragons and Snakes. In: Religion in Japan: A Web Handbook. Austrian Academy of Sciences, Institute for the Cultural and Intellectual History of Asia, August 24, 2014, accessed on September 19, 2014 .

- Homepage: Landestormuseum - Dragon Museum. City of Furth im Wald , accessed on September 19, 2014 .

- J. Georg Friebe: The dragon bestiary. Private website, 2007, accessed September 19, 2014 .

- Wiki: Dragon Wiki . Wikia , accessed January 29, 2018 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ DWDS - Digital Dictionary of the German Language. Retrieved October 21, 2019 .

- ↑ Lutz Röhrich : Dragon, Dragon Fight, Dragon Slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales . Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-008201-2 , pp. 788-789.

- ↑ a b Hans Schöpf: Mythical Animals. 1988, pp. 27-64; Lutz Röhrich: dragon, dragon fight, dragon slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, p. 790; Sheila R. Canby: Dragons. Pp. 42-46. John Cherry: mythical animals. Pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Entry: Dragon. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 3, column 1345.

- ↑ Lutz Röhrich: Dragon, Dragon Fight, Dragon Slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, pp. 810-811.

- ↑ Lutz Röhrich: Dragon, Dragon Fight, Dragon Slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, pp. 809-812; Entry: dragon. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 3, Salte 1339-1346; Sheila R. Canby: Dragons. In: John Cherry: Mythical Animals. Pp. 33-42.

- ↑ Lutz Röhrich: Dragon, Dragon Fight, Dragon Slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, pp. 791-794.

- ↑ Rudolf Simek: Middle Earth - Tolkien and Germanic mythology. Dragon and dragon lair. Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-52837-6 , pp. 133-139.

- ^ EJ Michael Witzel: EJ Michael Witzel: The Origins of the World's Mythologies. Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 148 ff.

- ↑ Julien D'Huy: Le motif du dragon serait paleolithique: mythologie et archeologie . Ed .: Bulletin Préhistoire du Sud-Ouest. tape 21 , no. 2 , 2013, p. 195-215 .

- ↑ Keš Temple Hymn. Line 78 with mention of a dragon in cuneiform script (around 2600 BC; English translation ).

- ↑ a b Christoph Uehlinger: Dragons and dragon fights in the ancient Near East and in the Bible. In: On kite tracks. 1995, pp. 55-101; Franciscus Antonius Maria Wiggermann: hybrid creatures. A. In: Dietz-Otto Edzard u. a .: Real Lexicon of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology . Volume 8, de Gruyter, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-11-014809-9 , pp. 222–245 (English; partial views in the Google book search).

- ↑ Arpine Khatchadourian: David of Sassoun: An Introduction to the Study of the Armenian Epic. Eugene OR, 2016, p. 19 ff.

- ↑ Patrick Absalon: Ladon, Hydra and Python: Dragons and Giant Snakes of Greek Mythology (and their Descendants in Art) . In: Dragons. In the zoological garden of mythology, pp. 37–58. Markus Jöckel: Where does the word dragon come from? In: On Drachenspuren , pp. 25–31.

- ^ Jo Farb Hernandez: Forms of tradition in contemporary Spain. University Press of Mississippi, 2005, no page numbers.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Mohen: Dragons, Demons and Dreki. In: Dragons. In the zoological garden of mythology. Pp. 63-68; Ludwig Rohner: Dragon saint. In: On kite tracks. Pp. 147-157; Lutz Röhrich: dragon, dragon fight, dragon slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, pp. 795-797; Entry: dragon . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages. Volume 3, Columns 1339-1346; Entry: dragon. In: Lexicon of Germanic Mythology. 2nd Edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 75-76.

- ^ Jacqueline Simpson: British Dragons. The Folklore Society, 2001, ISBN 1-84022-507-6 , p. 44.

- ↑ Dragon. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 7, Leipzig 1734, column 1374.

- ^ Ditte Bandini , Giovanni Bandini: Das Drachenbuch. Symbols - myths - manifestations. Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, pp. 185-189; Ludwig Rohner: The fight for the dragon. Hypotheses and Speculations in Dracology. In: On kite tracks. Pp. 158-167; Cornelius Steckner: Fantastic documents or fantastic living spaces? Pp. 51-63.

- ↑ Lutz Röhrich: Dragon, Dragon Fight, Dragon Slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, pp. 798-805; Sigrid Früh: The dragon in a fairy tale. In: On kite tracks. Pp. 168-173; Sigrid Früh: Fairy tale about the dragon. Pp. 129-140; Jacqueline Simpson: Fifty British Dragon Tales. Analysis. Pp. 79-93 (English).

- ↑ Wolfgang Münke: Mythology of Chinese antiquity. With an outlook on future developments. P. 48.

- ↑ Knut Edl. v. Hofmann: The dragon in East Asia: China - Korea - Japan. In: On Drachenspuren , pp. 32–47. Erna Katwinto and Dani Purwandari: The dragon in the mythology of Indonesian ethnic groups. In: Dragons. In the zoological garden of mythology, pp. 151–166. Xiaohong Li: The Realm of the Dragon. The creation of a mythical creature in China . Ibid, pp. 167-190. Sheila R. Canby: Dragons. In: John Cherry: Fabeltiere, pp. 42-46.

- ↑ Bernd Schmelz: Dragons in America. In: On Drachenspuren , pp. 48–54. Balaji Mundkur: The cult of the serpent: an interdisciplinary survey of its manifestations and origins, p. 143.

- ↑ Hakim Raffat: The dragon in the Islamic culture and its forerunners. In: On Drachenspuren , pp. 119–128. Frank Blis: Dragons in Africa and the Islamic Middle East. In: On Drachenspuren , pp. 129–146. Sheila R. Canby: Dragons . In: John Cherry: Fabeltiere , pp. 19-67.

- ↑ Michael Meurger: Dragons and Saurians . In: Auf Drachenspuren , pp. 174–181.

- ^ Ditte Bandini, Giovanni Bandini: Das Drachenbuch. Symbols - myths - manifestations. Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, pp. 216-231; Sandra Unerman: Dragons in Twentieth-Century Fiction. Pp. 94-101.

- ↑ Overview: The little training kites. Learn through play with success. ( Memento of August 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Ernst Klett Verlag, 2013, accessed on January 20, 2014.

- ^ Ditte Bandini, Giovanni Bandini: Das Drachenbuch. Symbols - myths - manifestations. Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, pp. 206-215.

- ^ Ditte Bandini, Giovanni Bandini: Das Drachenbuch. Symbols - myths - manifestations. Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, pp. 232-237; Doug Newsom: Bridging the gaps in global communication. Wiley-Blackwell, 2006, p. 128; Hanne Seelmann-Holzmann: The red dragon is not a cuddly animal. Strategies for Long-Term Success in China. Redline Economy, 2006, p. 101.

- ↑ Karl Shuker: Dragons. P. 10; Wilhelm Bölsche : Dragons. P. 40 ff .; describes the dinosaur hypotheses of the 19th century: Wolfgang Hierse: Cutting out the dragon's tongue . Pp. 17-22.

- ↑ Calvert Watkins: How to Kill a Dragon. Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. Oxford University Press, New York 1995

- ↑ Lutz Röhrich: Dragon, Dragon Fight, Dragon Slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, pp. 812-813; Elisabeth Grohs: Initiation. In: Hubert Cancik u. a. (Ed.): Handbook of Basic Concepts for Religious Studies. Volume 3, Stuttgart 1993, pp. 238-249; Knut Edler von Hofmann: The dragon in East Asia: China - Korea - Japan. In: On kite tracks. Pp. 32-47; Rüdiger Vossen: Dragons and mythical snakes in a cultural comparison. In: On kite tracks. Pp. 10-24; Walter Burkert: Mythical Thinking. In: Hans Poser (Ed.): Philosophy and Myth. A colloquium. Gruyter, Berlin 1979, p. 28.

- ↑ Lutz Röhrich: Dragon, Dragon Fight, Dragon Slayer. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3, Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, pp. 813-815.