Ming Dynasty

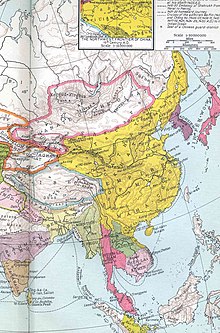

The Ming Dynasty ( Chinese 明朝 , Pinyin Míngcháo ) ruled the Empire of China from 1368 to 1644 , replacing the Mongolian rule of the Yuan Dynasty in China and ending with the Qing Dynasty in the 17th century .

The state under Hongwu

The dynasty was founded by the rebel leader Zhu Yuanzhang , who led a splinter group of the Red Turbans in the uprisings against Mongol rule. In 1363 he decided the sea battle on the Poyang Lake against his most important rival, the "Han" prince Chen Youliang , for himself and also eliminated his remaining opponents in the following years. At the same time, he began to organize proper administration and issued 38 million coins as early as 1363. In 1368, his army under General Xu Da drove Khan Toghan Timur out of Beijing and ended Mongol rule.

As the first emperor of the Ming dynasty , Zhu Yuanzhang chose the government motto " Hongwu ". During his reign, economic reconstruction was the focus of efforts. There were countless building and irrigation projects through which half a million to five million hectares of land were developed each year. Grain tax income tripled in six years. It is estimated that in 20 years up to a billion trees were planted (fruit trees, trees for the fleet, mulberry trees for silk production ).

There was also tremendous bureaucratic effort during the Ming period . Compared with the liberal Song era, they resulted in an absolutist government. As early as 1380 there was a trial of the emperor against a former confidante, in which 15,000 people were involved. This meant that all power was concentrated on the emperor, to whom all ministries were now directly subordinate (i.e. without an imperial secretariat). The office of grand chancellor or prime minister was banned for the future. In 1385 and 1390 the emperor repeated these processes. According to contradicting opinions, Hongwu was hardly accessible at the end of his term of office, he ruled with the help of secret officials and the secret police (1382: the "guards with the brocade dresses"). He also had numerous officials and military officers executed out of sheer suspicion.

Nevertheless, the first Ming emperor laid the foundation for a stable state apparatus that survived at least two and a half centuries with population growth and major economic changes and which served as a model until 1911 with only marginal changes.

Management problems

Hongwu's ideas shaped the state structure. The population was divided into families of farmers, soldiers and craftsmen, each with its own ministry (each with its own tax collection) and main settlement areas, and changes in occupation were suppressed. In addition, ten families ( lijia ) were made collectively responsible to the administration for taxes, public services and order. Since the number of officials was insufficient for the control, there were soon changes of location and occupation, combined with deviations in tax revenues and - even worse - the displacement of the poorer members of a lijia in the country.

In the army as early as the middle of the 15th century (the Tumu debacle in 1449), the disadvantages of Hongwu's population were very clear. The first Ming emperor created a class of soldiers through inheritance of the profession and thought that through procreation there would be a permanent, self-sufficient supply of (quasi genetically) suitable soldiers. Since he had farmland made available for the soldiers, no military budget was provided. The basic problem with this was that the soldiery represented an employment agency, for which one was intended at birth, without a love of the profession, the country or the dynasty was connected with it. The system failed when the emperors showed no interest: the soldiers became servants of the officers who appropriated the army's farmland and let the soldiers work for them. The officers also sold exemptions from military service. Wealthy soldiers simply let poorer substitutes fill in, or the soldiers simply deserted.

The social structure soon got out of control, so that these regulations had to be changed or made more flexible in the second half of the 15th century, after social unrest had broken out several times and more and more people evaded tax and military service. Thereafter, for example, the army increasingly used mercenaries ( minzhuang ) and took measures to finance them, so that the army then consisted partly of conscripts and partly of mercenaries. The number of state subordinate artisans ( zhuzuo ) declined in a similar way; instead, semi-free artisans ( lunban ) were increasingly used , and in 1485 and 1562 they were allowed to redeem their obligations with silver payments.

The administrative problems already described were joined in the 15th century by the rule of the palace eunuchs and the harem ladies , who had great influence on the private council ( Neige ) , which had been almighty since 1426, and soon also over the secret police. In contrast to state officials, eunuchs did not have a regulated career ladder with examinations, but were completely dependent on the personal whims of the emperor and were played off by him as a tool of absolutism against regulated state officials. Quite a few emperors even withdrew as far as possible from politics, and the resulting tension between the eunuchs (mostly of poor origin from northern China) and the high officials (southern China's affluent and educated elite) led to uninterrupted intrigue and arbitrariness , which affected the state internally decomposed, especially in the period 1615–1627 or under the emperors Wanli and Tianqi .

economy and trade

There was strong internal expansion during the Ming period, given the economic rebuilding of Hongwu's time, the boom in domestic trade in the 16th century, the revival of military colonies, and population growth from 1550 onwards.

Complicating economic progress was the Confucians' traditional disdain for trade and merchants, which peaked in the Ming period. But contrary to legend, China did not stop its foreign trade after Zheng He's expeditions in 1433 and did not indulge in any real isolationism , as was practiced in Tokugawa Japan . The Ming were able to maintain the Middle Kingdom as the most important maritime and economic power in East Asia. However, there was a spiritual turn inward under the Ming. Associated with this was a more conservative attitude in politics, society and intellectual life. In addition, in the early 16th century, trade restrictions came under Emperor Jiajing as a result of a conflict with Japan. To prevent smuggling to Japan, all ocean-going ships were destroyed in 1525. After this had hardly any effect, an attempt was made in 1551 to stop all foreign trade. The consequence of the bans was an even bigger boom in smuggling and piracy in the coastal areas - the traders there simply changed their source of income. As early as 1567, all restrictions had to be dropped again.

But the 16th century, despite the conservative attitude of the civil servants, also represented an enormous climax in economy and culture. The new European colonies in America can be seen as one cause . Most of the silver mined there was spent by Portugal and Spain in China to purchase goods for the European market. At the same time, silver money replaced paper money again , which should stabilize the currency. Another reason for the boom was the low level of taxation, which was standardized in the 16th century. Furthermore, the strong regional differentiation within the total production of the empire should be mentioned, which promoted the domestic trade in mass consumer goods, from which the merchants drew their profits.

After 1520 there was a boom in wholesale trade and handicrafts and technical advances and innovations in handicrafts (e.g. in weaving and printing), agriculture (new crops such as the sweet potato, partly thanks to the Portuguese), and also the military. Rice and grain were traded in particular (the latter for salt vouchers to the border areas), salt and tea, cotton and silk for the textile market, and porcelain. Even printing and bookshops were profitable given the educational needs of the middle population. Wholesale merchants, business people and bankers rose again as suppliers to the state. A wealthy Chinese bourgeoisie flourished, with the fortunes of individual traders amounting to a million silver ounces and more.

During the Ming period, military colonies (identification: place names ending with -ying ) were established at the borders. Their military protection promoted the Chinese settlement there, which was at the expense of the local population (Thai, Tibeto-Burmani, Miao, Yao) and provoked numerous clashes (e.g. 1516 in Sichuan under Pu Fae). Around 1550 an extraordinary population growth set in, due to the continuous improvement in rice cultivation since the 11th century (Champa rice - high-yield, robust, and finally also fast-growing: 60 days from transplanting to harvest) and the additional use of crop rotation when growing grain was caused or at least favored.

Efforts were made under Chancellor Zhang Juzheng (1525–1582) to alleviate the burden on small farmers.

Foreign policy

The Ming's greatest foreign policy burden was the changeful fighting with the Mongols - but this time in Mongolia. It is worth mentioning the victory of Lake Buinor in 1387, which soon led to the Kublaids being disempowered . However, the western Mongols (especially the Oirats ) now came to the fore and new Chinese campaigns were necessary. This was one of the strategic reasons why Emperor Yongle had the imperial capital moved from Nanjing to Beijing from 1406 . In this context, the Kaiserkanal was also expanded for the transport of rice.

The Ming suffered a serious defeat in 1449 when the Western Mongols under Esen Taiji triumphed at Tumu and captured the inexperienced Emperor Zhengtong . Pressure from the Mongols renewed itself in the 16th century when the Ming Dayan and Altan Khan provoked trade boycotts. The army acted increasingly defensively against the Mongol raids (not least for reasons of cost), so that the famous Great Wall of China was expanded to its present-day status to protect against raids .

The sea voyages under the Muslim grand eunuch and Admiral Zheng He from 1405 onwards are as unique as the Wall. Such voyages were already common during the Song era , but now they were carried out officially and exclusively financed by the state. Their main purpose was to show the world that the Chinese were again ruling China. The commercial benefit played a subordinate role, so that after 1433 such a naval policy could be dispensed with again. When the Portuguese took over Macau in 1557 with the permission of the imperial court , China was subject to the restrictions imposed by Emperor Jiajing , which is why there was no sign of Chinese naval power; instead, Japanese pirates, the Wokou , ruled the coasts. Only the Chinese victories after 1556 slowly put an end to this.

Culture and religion

In terms of culture, there are some great novels of the time: Journey to the West , Tale of the Riverside , The Story of the Three Kingdoms, and the erotic novel Jin Ping Mei . There has been a further development of theater ( opera and drama ) and painting . Ming porcelain should be mentioned from the field of practical art.

Religion was an important part of the life of the Chinese during the Ming Dynasty. The dominant religions were Buddhism , Daoism and the worship of a variety of deities. Buddhism advocates the doctrine of the infinite cycle in which the body is caught between birth and rebirth. Life is seen as shaped by suffering, greed and hatred, and this context is contrasted with the four noble wisdoms. Daoism is a Chinese philosophy and worldview ("teaching of the way") in which the search for immortality is an important part. He particularly flourished under the Ming Emperor Jiajing (1521–1567). As a devout and devoted supporter of the Dao School, the emperor had three famous temples built in Beijing: the Sun Temple, the Earth Temple and the Moon Temple.

Over time, Christianity has got a special role in China. While the Reformation spread in Europe with Luther at its head, Roman Catholic missionaries tried to spread their religion in Asia and China. Franciscans, Dominicans, and Jesuits were among the missionaries. They tried to get access to the Chinese through western advanced science and culture. Many Chinese were impressed with their knowledge of astronomy, calendars, mathematics, hydraulics and geography. All missionaries were led by the Jesuits, a Catholic religious and living community. At their head was Matteo Ricci , who tried to bring Buddhist and Daoist teachings into harmony with Christianity. However, many Chinese were skeptical. Only long after Ricci's death, in 1610, did the Jesuit mission really gain a foothold and become an important part of the Chinese state well into the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911).

The public finances

The inadequately organized state finances were an important factor in the fall of the dynasty. They go back to Hongwu's misjudgments, even if they still had a plus to show under him. The first Ming emperor relied on rural self-government ( lijia etc.) on the basis of Confucian morality, on the self-sufficiency of the army, etc. and accordingly reduced civil administration to a minimum (8,000 people). Hongwu also set very low taxes and (given its origins) took no other economic activities seriously other than agriculture. In addition, the brutal monarch suppressed other economic ideas (e.g. proposals for higher taxes) and this had a lasting effect, since the Confucian civil servants always used to refer to the founder of the dynasty.

Even under Yongle , the weaknesses of his institutions and measures became apparent. For the renewal of the Imperial Canal, the relocation of the capital to Beijing, the overseas expeditions of the Zheng He and of course the campaigns against the Mongols, the emperor needed additional resources in terms of people and material. Yongle should have raised his father's low taxes to solve the financial problems. He did not, instead, farmers and artisans were asked to provide much more free services for the state, based on local decisions as needed, not according to a plan. Resistance was suppressed with the help of the secret police.

In view of a quasi-absolutist form of government and a weak emperor, little changed in the financial situation. “Replacement governments” such as influential grand secretaries and eunuchs did not have the necessary authority and got bogged down in factional battles at court. The local elites (i.e., large landowners) shattered by Hongwu recovered. They refused to serve the state and, around 1430, embezzled taxes in some districts for years. The government made concessions to them and lost more and more room for maneuver. They no longer dared to raise taxes that were too low, relied too much on agriculture, could not suppress corruption and compensated for deficits through locally limited and unevenly distributed additional obligations (2nd half of the 15th century).

Despite better conditions in the 16th century (potatoes, inflow of silver, technical advances, upswing in wholesale trade, etc.), the state was never able to get its financial problems completely under control. After all, a simplification of the tax seems to have triggered the economic boom of the 16th century. The tax yitiao bianfa (ie "one-branch system") was created and systematized between 1530 and 1581, merged taxes and services into a single tax, was calculated on the basis of the men ( ting ) and not the households, was largely in silver to pay and had updated survey data. It did not meet the expectations placed on it, but the merchants knew how to benefit from it.

The upswing of the 16th century also had its downsides: the boom in the cities deprived agriculture of investment funds, no more investments were made in irrigation systems for growing rice, and the landlords tried to cut as much as possible in order to be able to pay for their city life. Income in the country therefore fell rapidly, while in the cities (craftsmen, manufacturing workers) it rose. With the price increases triggered by the boom and the supply of silver, the value of agricultural products and arable land fell (from 100 ounces of silver per mou of land in 1500 to 2 ounces in the 17th century).

All of this did not endanger the state, but only one stratum of the population and could have been corrected, but the dynasty still saw the farmers as the main source of income and did not adapt taxation to the changed economic conditions. They asked for more grain and labor, or cash, but the farmers didn't have the latter, because that was concentrated in the cities. Then there is the population growth. At the same time, government spending was substantial. Depending on the source, 26 or 33.8 million silver ounces were spent on the Imjin War in Korea at the end of the 16th century and then 8 or 10.4 million ounces of silver on Wanli's tomb. The maintenance of the imperial family eventually devoured half of the tax revenue of Shanxi and Henan. This went so far that a marriage ban was issued for the princes (1573–1628) in order to get the costs of their appanages under control.

The imbalances eventually led to the collapse of the state as the peasants in central provinces rose and the dynasty no longer had the financial means to pay the troops, provide for them, and restore order.

Fall of the Ming

The fall of the dynasty heralded attacks by the Manchu , which were followed by violent peasant revolts. When the Ming army killed family members of the Manchu prince Nurhaci († 1626) in 1583 , he became the enemy of the Ming. In 1619 he defeated four Ming armies advancing against him at the same time on Mount Sarhu near Mukden . In addition, repeated bad harvests in 1627/28 triggered a famine. There were peasant uprisings in Shaanxi and Shanxi , which were organized under Gao Qingxiang , Li Zicheng and also Zhang Xianzhong and ultimately aimed at the overthrow of the dynasty. In April 1644, Li Zicheng entered Beijing and declared himself emperor, the last Ming emperor Chongzhen hanged himself.

Li Zicheng was subject to misjudgments about the financial situation in Beijing. As a result, he was unable to maintain order in the capital and, under questionable circumstances, took action against General Wu Sangui , who commanded the last remaining Ming army on the northern border. Wu Sangui then joined the Manchu, whereby their regent, Prince Dorgon , was able to advance to Beijing on behalf of the then six-year-old Manchu Emperor Shunzhi , (1644–1661) , expel Li Zicheng and establish the Qing Dynasty .

Until 1662 the evacuated or released family members of the Ming provided some counter-emperors in southern China , but they could only watch the fall of their dynasty and their empire. The old capital Nanjing was its most important base under the Prince of Fu in 1644/45. There can be no question of an orderly resistance, however, because the peasant uprisings had created militarized local elites all over the cities and former Ming commanders held important corridors and fortresses independently, i.e. In other words, when in doubt, they also fought against each other for control of an army. Li Zicheng's rebel army, which had fled to Xi'an , and another under Zhang Xianzhong in Sichuan Province (see article Daxi ) also diminished the defense power of the Southern Ming against rice riots, smuggling and pirate incidents and the like. Ä. not to mention.

In contrast, with a general amnesty and a policy of pacification, the Manchu were able to attract new officials and organize the north. Their army was more powerful and showed more solidarity with one another, and was able to maintain discipline with the corresponding orders. Supply troops served to keep them from looting. Even so, their warfare was selectively cruel. B. After the battle for Yangzhou in 1645 they carried out a massacre that resulted in the subjugation of the Yangtze River Delta. Shortly afterwards, Nanjing surrendered. Two other well-known massacres took place (after an uprising) in Jiangyin and Jiading , and although defected northern Chinese troops and troop leaders were also at work there, they served as agitation against the Manchu 250 years later.

literature

- Timothy Brook: The Troubled Empire. China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 2010.

- Jonathan Clements: Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill 2005, ISBN 0-7509-3270-8

- Jacques Gernet: The Chinese World. Suhrkam, Frankfurt 1997, ISBN 3-518-38005-2 .

- Ray Huang: 1587, A Year of No Significance. The Ming Dynasty in Decline . Yale University Press, New Haven 1982, ISBN 0-300-02518-1

- Frederick W. Mote: Imperial China. 900-1800. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA et al. 1999, ISBN 0-674-44515-5 .

- Denis Twitchett , Frederick W. Mote: The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 7. The Ming Dynasty 1368-1644. Part 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1988, ISBN 0-521-24332-7

- Denis Twitchett: The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 8. The Ming Dynasty 1368-1644. Part 2. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1998, ISBN 0-521-24333-5 .

Web links

- Text about the Ming Dynasty 1

- The Ming Dynasty at Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010 ; Retrieved January 26, 2014 .

- Notable Ming Dynasty Painters and Galleries at China Online Museum (English)

- Ming Dynasty art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (English)

- Chinese History - Ming Dynasty . ChinaA2Z.com (domain no longer available) September 23, 2009, archived from the original onJanuary 23, 2011; accessed on November 29, 2015(English, original website no longer available).

- Search for Ming dynasty in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Search for Ming Dynasty in the German Digital Library