Chinese painting

The Chinese painting is an expression of Chinese art and the Chinese culture . Like Chinese historiography, it can look back on a long period of time. Albeit from around 1500 BC. BC there are hardly any works, so in some documents names of individual artists are mentioned.

Essence

In contrast to painting in the West , painting in China is not concerned with originality and a “personal” style. Rather, it continues a school tradition; many painters only find their own style in old age. This gives Chinese images a certain timelessness.

For the European observer only the works from the Tang Dynasty become easier to grasp; At that time landscape painting came up, which is very different from occidental landscape painting, but at least offers a good introduction. The true-to-life representation of the landscape is unimportant for the Chinese painter; what matters more to him is the mood and atmosphere that should arouse and awaken feelings in the viewer. Otherwise, it is not so much about the exact replication of an object, but about capturing its essence, its development pattern, its movements.

The two cultures also differ in the treatment of the images. In the West, pictures are framed and fixed in a fixed place on the wall, while Chinese pictures are painted on rolls of silk or paper and are only brought out when you want to look at them.

The base for the pictures is another difference between the two cultures, which contains an even greater difference. The silk or paper rolls used are sensitive and do not allow any corrections whatsoever, which forces the painter to let the picture emerge in his head before he puts it on paper. So the mental requirements are completely different.

While western painters put a lot of effort into depicting light and shadow, a Chinese ink painter represents sharpness or contour primarily through the targeted use of the wet or dry painting technique, which the well-known Daoist Yin-Yang contrasts in art reflects. The wet line stands for the feminine, soft, diffuse yin principle, the dry line for the masculine, hard and light yang.

Since Chinese landscape paintings are often also used for meditation , the painters forego the excessive use of color, which would only distract the viewer. Instead, color is heavily used in the other four main areas of Chinese painting. These are: portraits , narrative genre pictures , pictures of animals and pictures of flowers or plants . In these areas, outlines made of Indian ink are mostly dispensed with, which has earned them the designation boneless . The bones, however, give the landscape d. H. Outlines the contours.

The depictions of ink painting contain a lot of hidden symbolism, which gives the picture an additional dimension for those who are able to interpret it. For example, a picture of a crane with a pine tree as a present for retirement expresses the wish for a long life.

The use of lettering that harmonizes with the picture is another peculiarity of Chinese painting and is achieved through the uniform guidance of the brush.

In China, studying this traditional painting requires a long learning process and a lot of practice. The student copies the pictures of his “master”, which are often copies of older works themselves, so that a picture is often painted by generations of students in their own style. The students acquire as much theory and practice as possible in order to create their own original using traditional technology.

A work of Chinese ink painting should have “ Qi ” (or Chi), a term that is difficult to translate and which means something like “life”, “life of its own” or “energy”. The mood and character of the artist also influence the work, so that one should not overlook the energy of its creator when interpreting a picture. As a Chinese teacher once noted, painters from the Orient have the cultural background in their souls, while an artist from the West has to create the right atmosphere first.

history

Tang Dynasty (and the time before)

While the pictures in the early period of the first 600 years AD were characterized by ethical, moral and religious themes, hunting scenes and the illustration of cults of the dead, painting increasingly began around the fourth century, along with the discovery of the landscape To develop sensitive artistic forms of expression in brushwork and painting style, which pointed beyond the mere representational quality of what is shown. Wang Hsi-chih and Ku K'ai-chih (Gu Kaizhi) are two exemplary artists.

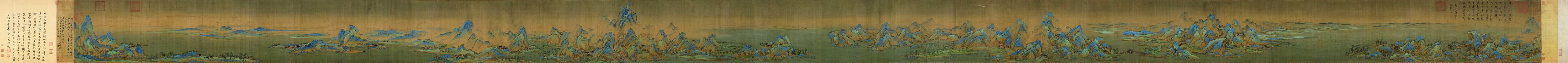

Landscape painting from the time of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) found its remarkable peculiarity in the so-called “blue-green style” of the painter Li Sixun and his son Li Zhaodao . Blue and green were the two dominant colors, especially in the color scheme of the mountain slopes. In addition, painting of the Tang period was influenced by Buddhist images from India . In particular, religiously inspired fresco painting reached its height in the eighth century, which has never been reached since. The time under the rule of Emperor Ming-huang (= Tang Xuanzong 712 / 13–756) is referred to as the classic Golden Age of the "Radiant Majesty". Works by the artists Han Kan (Hán Gàn) and Wang Wei have survived from this period, which was important for art . Wang Wei was best known for his monochrome ink painting.

In addition to outstanding works of landscape painting, flower and bird pictures, court portrait painting also enjoyed high recognition. The famous temple frescoes (eg "the death of the Buddha") by the painter Wu Tao-tse (680–760), who was presumed to be the greatest genius , were destroyed in the great persecution of Buddhists in 843.

Song Dynasty

Chinese painting reached a high point in the Song Dynasty . Ink painting, which enjoys special status in China, also developed in it.

landscape

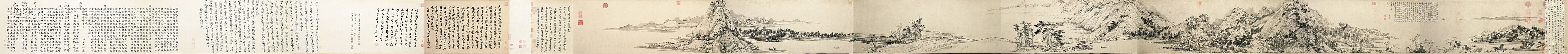

The landscape paintings, for example, gained a more subtle expression during this period. The immensity of spatial distances was indicated, for example, by blurry outlines, by mountain silhouettes disappearing in the fog, or by an almost impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena. Nature is captured as a majestic whole, from which human activity is largely banned. A compositional technique was popular with such paintings, which forces the essential elements in the foreground on this side of a picture diagonal together, while the rest of the picture suggests infinity. As an example, the work attributed to Lǐ Táng (李唐; 1047–1127), Countless Trees and Strange Peaks, can serve. The opposite position was represented by Guō Xī (郭熙; 1020-1090), according to which it was the task of a painting to give the viewer the impression that he was on the spot ( early spring , autumn in the river valley ). In the later works of the southern Song dynasty, however, the focus of the later works of the southern Song dynasty, especially those of the Ma-Hsia school, is nature that is more “tamed” and “enjoyed” by art-loving people. Mǎ Yuǎn's (馬 遠; approx. 1155–1235) famous On a Mountain Path in Spring belongs here, but also the works of Xià Guīs (夏 珪; approx. 1180–1230).

Figure painting

Figure painting was also further developed . The small things peddler in Li Sung 's picture of the same name, as well as his customer with their five children, appear very realistic, if not to say “earthly” . The colored people, described by some art historians as “almost Middle Eastern” in their miniature-like figuration, are of a completely different kind in the anonymous history painting The Journey of Emperor Minghuang to Shu or in Chao Yen's Eight Horsemen in Spring . As in earlier periods, people continue to be shown in awe-inspiring contemplation in front of nature, but no longer necessarily disappear in front of majestic, overwhelming scenery, but take central positions. To be mentioned in this context are in particular the noble scholar who presumably portrays the poet Tao Yuanming under a willow tree , but above all Mǎ Lin's (馬 麟; approx. 1180–1256) listening to the wind in the pines .

animals and plants

Animal and plant representations were also a central subject of Song painting . The imperial academician Cuī Bái (Ts'ui Po, 崔 白, active 1068-1077) was considered the greatest master of this genre . He impressed his contemporaries by the fact that he used to paint his creations directly with a brush on silk without any preliminary study and was even able to draw long straight lines without a ruler. His fame is based on only one surviving picture of the hare and jay , which is one of the greatest works of Chinese painting . Another great bird and flower painter of the era was Emperor Huīzōng (徽宗; 1082–1135), from whom, among other things, the dove on the peach branch comes. The academy artist Mao I was considered a gifted cat painter . Wen Tong (文 同; 1018–1079) from the 11th century was famous for his bamboo ink pictures. He was able to paint two bamboo stalks at the same time with two brushes in hand. Because of his extensive experience, he was able to draw them from memory without any problems.

Buddhism

Another direction in song painting eventually took up Buddhist themes. Sunken adepts of Zen Buddhism , which was just developing at the time, were particularly popular , for example in Shih K'o's picture role Two Patriarchs in Inner Harmony . But Orthodox Buddhism was also reflected in the works of the song artists in many ways. Was called Zhang Shengwen (張勝溫; the second half of the 12th century.) In the National Palace Museum in Taipei kept Hand Roll with the representations of the various Buddha - incarnations .

abstraction

Ultimately, the particular to Sū Dōngpō (蘇東坡; 1037–1101), Confucian , but also Zen Buddhist influenced and sometimes surprisingly modern-looking Wen-Jen-Hua school had a pioneering effect . She broke with the long-undisputed dogma that painting should reproduce its object as naturally as possible. According to Su Dongpo, however, the topic only serves as a raw material that has to be transformed into an image. The expressive content of a picture comes from within the artist and does not necessarily have to be related to what is represented. Often, extremely unconventional painting techniques, generally regarded as “amateurish”, were used. The idea of the Wen Jen Hua school is exemplified in Liáng Kǎi's (梁楷; 1127–1279) famous portrait of Lǐ Bái (李白; 701–762), in which the poet is skilfully sketched with a few brushstrokes. He called himself "Crazy Liang" and spent his life drinking and painting. Towards the end of his life he withdrew from the world and entered a Zen monastery. Other important representatives of this direction are Mǐ Fú (米 芾; 1051–1107), of whom no works have survived , his son Mǐ Yǒurén (Mi Yu-jen 米 友仁; 1086–1165), and Mùqī (牧 谿; 2nd half 13th century), who is best known for his strangely abstract mother monkey with child , and finally Wáng Tíngyún (王庭筠; 1151–1202).

Yuan Dynasty

In the Yuan Dynasty , a time of Mongolian rule, painting was predominantly in the hands of learned literary painters. Most of them had withdrawn from public life in silent protest against the new political situation and pursued their art in private. A stronghold was in the southern Yangzi delta between Hangzhou and the river mouth. But there were also painters, especially in the early period before Kubilai Khan's death in 1333, who also held high offices at the Yuan Court in Beijing, such as the minister Zhào Mèngfǔ (趙孟頫; 1254-1322) or the court president Gāo Kègōng ( ō克恭; 1248-1310).

The artists of the Yuan period largely rejected the artistic legacy of the southern Song dynasty. They regarded the academy style at the old imperial court as too romanticizing, too "pleasing", while Buddhist Zen painting was "lacking in discipline", especially because of its radical brush techniques. Rather, it was linked to the northern song , but above all to the older Tang art, from which the widespread “green-blue manner” was adopted. The tonal gradations of the late songs have disappeared in favor of bold, striking colors, space and the environment are hardly used as design elements. Compared to their role models, the Yuan pictures were often reviled in art history as "reluctantly hypothermic", as "dispassionate".

On Huáng Gōngwàng (黄 公 望; 1269-1354), however, the connection between this reluctance and “strength and character” was valued. His late work "In den Fuchun-Berge Verweilend" is considered to be one of the most influential pictures in Chinese art history and was accordingly often copied, quoted and received by subsequent generations of painters. Ní Zàn (倪 瓚; 1301–1374) is also recognized because of his - according to the Chinese view in the best sense - "charmless" style and the deliberately "amateurish" painting technique that the literary painter from his professional colleagues, the socially less respected "professional painters" difference. Nizan placed little value in particular on spatial reproduction and the naturalistic representation of objects.

Other important representatives of Yuan painting were Qián Xuǎn (錢 選; 1235–1305), Wú Zhèn (吳鎮; 1280–1354), Sheng Mou and Wáng Méng (王蒙; 1308–1385).

Ming Dynasty

Zhe school

In the field of painting, two schools in particular established themselves in the Ming period : One of them, the later so-called Zhe school , followed on from the tradition of the academies of the southern Song dynasty and particularly revived the style of Ma Yuan . Its members were mainly professional painters at the court of the Ming emperors. Because of their style, which was perceived as inadequate compared to their role models, but also because of their low social position, they were met with disdain by the scholarly officials. The main master of the Zhe school, Dài Jìn (戴 進; 1388–1462), died of poverty and despair after his frustrated retreat into private life.

Wu school

Towards the end of the 15th century, the Wu School was established in the Suzhou area . “Wu” is an old name for a landscape on the lower reaches of the Yangzi River near the city. The school direction was mainly favored by learned amateur painters, whose financial independence enabled them to devote themselves fully to the arts. The most important representatives include the founder of the school Shěn Zhōu (沈周; 1427–1509), as well as Wén Zhēngmíng (文徵明; 1470–1559), Táng Yín (唐寅; 1470–1523) and Qiú Yīng (仇 英; 1st half 16th century). The Wu School continued the landscape painting of the northern Song as well as the tradition of the Yuan dynasty and tied in particular to the art of Ní Zán and the learned literary painting .

At the end of the dynasty, theoreticians also appeared, in particular Dǒng Qíchāng (董其昌; 1555–1636), to whom the division of Chinese painting into a north and a south school goes back.

Qing Dynasty

At the beginning of the Qing dynasty , the literary painters had finally prevailed; In contrast, the professional painters hardly played a role.

Orthodox school

The painters of the Orthodox school continued to orientate themselves on traditional models, in particular on the Ming painter Dǒng Qíchāng . The pictures were carefully constructed line by line and tone by tone, avoiding safer, unbroken lines and simple surfaces. Technical tricks and the achievement of special effects were also largely avoided. The school is mostly viewed as epigonal and secondary in art history outside of China. Important representatives are the four brothers Wang, Wáng Shímǐn (王時敏; 1592–1680), Wáng Jiàn (王 鑒; 1598–1677), Wáng Huī (王 翬; 1632–1717, see also: South Journey of Emperor Kangxi ) and Wáng Yuánqí (王 原 祁; 1642–1715) as well as Wú Lì (吴 历; 1632–1718) and Yùn Shòupíng (恽 寿 平; 1633–1690) ("The Six Great Orthodox"). They lived in relatively close contact with everyday bourgeois life and often held high official posts.

Individualistic school

This contrasts with the so-called individualistic school that occurs at the same time . Their representatives mostly led a rather volatile life and withdrew to monasteries and hermitages. They cultivated a freer style, often working with dissolved, disembodied forms as well as light and shadow and thus created, among other things, very atmospheric, inspired landscapes. Sometimes they showed eccentric features like the Zhū Dā (朱 耷; 1626–1705) , which tended to alternate between silence and inarticulate screaming . Shí Tāo (石濤; also Daoji; 1642–1707), however, also worked as a painting theorist. He condensed his numerous visual suggestions into a limited and ordered system of forms, which are the origin of all phenomena in the world. He became known u. a. through an illustration of Tao Yuanming's story of the peach blossom spring . Other important representatives of the individualistic school are Kūn Cán (髡 殘; 1610–1693), Hóng Rén (弘仁; 1603–1663) and Gōng Xián (龔 賢; 1618–1689) (so-called "Nanking school").

Eight eccentrics from Yangzhou

In the 18th century, the eight eccentrics of Yangzhou were added as the third painting school of the Qing period . They followed up on the freer style of the individualists, but sometimes developed downright bizarre painting techniques. Gāo Qípeì (高 其 佩; 1660–1734), for example, already a recognized painter at the age of eight, painted his pictures with hands and fingers, but above all their nails. Jīn Nóng (金 農; 1687–1764) used to flirt with an inextricable mixture of a lack of technical talent and "conscious" awkwardness and to confuse the contemporary audience with his flattened, impasto, almost naive -looking creations ("Young Man at the Lotus Pond") . Huá Yán (華喦; 1682–1765), best known for his bird paintings, made a name for himself as a master of omission and restrictions . Lastly, Luó Pìn (羅 聘; 1733–1799) is remembered by posterity through the melancholy, expressive portrait of his friend I-an.

Modern

After the fall of the Qing dynasty, a previously unknown differentiation took place in Chinese painting. Many artists broke away from traditional models under diverse political and cultural influences and developed highly individual styles.

Qí Báishí (齐白石; 1864–1957) took over elements of traditional scholarly painting, but developed the technique considerably. His Xieyi-style pictures are characterized by simple structures and quick, skilful brushstrokes. His preferred subjects include rural scenes, farm implements, and above all, particularly lifelike depictions of small animals such as crabs , crabs and tadpoles , mice , birds and insects, as well as plants such as peonies , lotus, pumpkins and bananas . Human figures, however, often appear awkward and naive in his pictures. Some pictures also have humorous traits.

Xú Bēihóng (徐悲鸿; 1895–1953), for example, who studied at the National Academy of Fine Arts in Paris and later a. a. Having toured Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy imported European techniques into Chinese painting. He became known as a painter of galloping horses . In the 1930s, he created influential paintings such as Tian Heng and Five Hundred Rebels , Jiu Fanggao, and Spring Rain over the Lijiang River .

Lín Fēngmián (林風眠; 1900–1991) , who was also trained in France , also oriented himself towards European art, albeit towards more modern works . For a long time he was ostracized by the official cultural policy of the People's Republic; Later, however, Lin's works were judged more impartially. His work is characterized by bright colors, eye-catching shapes and rich content.

The flower and landscape painter Pān Tiānshòu (潘天壽; 1897–1971), however, always emphasized the need to distance himself from European painting and instead took up historical models such as Zhū Dā and Shí Tāo . From the academy painters of the Southern Song Dynasty , he took over the work with sharp contrasts and large empty areas. Sometimes he also used his fingertips to paint. Pan's most significant works include After the Rain , Flowers on Yandang Mountain, and Mountains After the Rain .

The art of Fù Bàoshí (傅抱石; 1904–1965), who was trained in Japan , also ties in with the individualistic scholar painting Shí Tāo , but was also fed by influences from the Japanese Nihonga school, which Fu had got to know during a two-year study visit. His sometimes contradicting and contradicting style are characterized by swift yet accurate lines and dry texture , as well as extensive washes . Thematically, landscapes dominate, often with waterfalls or raging mountain streams , but also depictions of historical and mythological figures.

Lǐ Kěrǎn (李可染; 1907–1989), sponsored by Li Fengmian and Xu Beihong, also specialized in landscape painting . The motto "Write a biography for the mountains and rivers of home" is ascribed to him. While he was initially more inclined to sketchy sketches, as he got older he increasingly tried to intensify his perception of nature artistically. He, too, often worked with empty surfaces and paid great attention to the relationship between light and shadow.

The Taiwanese artist Chen Chengpo (陳澄波; 1895–1947) painted mainly in oil . Stylistically, his works are particularly influenced by European painting and take up the characteristics of impressionism , but also those of Cézanne and Gauguin .

People's Republic of China

After the communists came to power in 1949, the style of socialist realism developed in the Soviet Union was also propagated, on the basis of which art was often mass-produced. At the same time, a rural art movement emerged, which dealt with everyday life in the country in particular on murals and in exhibitions. Traditional Chinese art experienced a certain revival after Stalin's death in 1953 and especially after the Hundred Flower Movement 1956-57. One of the most important painters who have devoted themselves to the revival of traditional Chinese painting since the 1960s is the impressionist of Chinese watercolor and ink painting, Cao Yingyi , who was born in Nanjing in 1939 . His hardly less well-known wife, Gu Nianzhou , made a name for herself with impressive flower pictures.

Other than the officially sanctioned styles, alternative artists were only able to assert themselves temporarily, with phases of strong state repression and censorship alternating with greater liberalism.

After the suppression of the Hundred Flower Movement and especially in the wake of the Cultural Revolution , Chinese art had largely fallen into lethargy. After Deng's reforms from around 1979, however, a turning point emerged. Some artists were allowed to travel to Europe for study purposes; exhibitions on contemporary Western art and the publication of the sophisticated art magazine Review of Foreign Art were also tolerated. While the artist group Die Sterne leaned on the traditions of European classical modernism, the painters of the "Schramme" endeavored to master and artistically process the suffering brought on by the cultural revolution in China.

The reins were pulled tighter in 1982, when the government defamed contemporary art as “bourgeois” as part of a “campaign against religious pollution”, closed several exhibitions and staffed the editorial team of Art Monthly with cadres loyal to the line.

As a reaction to the now spreading artistic wasteland, the '85 movement emerged , which referred to Dadaism , especially Marcel Duchamp , as well as American Pop Art and contemporary action art. At least she was able to organize a number of important exhibitions, such as the “Shenzhen Zero Exhibition”, the “Festival of Youth Art” in Hubei in 1986 and the “China / Avant-garde” exhibition in Beijing in 1989. Despite the massive repression and obstruction of Movement 85, she remained Alive for years and ultimately also contributed to the protests in Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

After their bloody suppression, Chinese art came to a standstill again. Some artists emigrated in the period that followed, others continued to work underground. During this time, however, political pop emerged , which combined elements of socialist realism with American pop art in order to castigate the takeover of capitalist structures based on a still authoritarian state system. Representatives of this direction are the "New History Group" and the "Long-tailed Elephant Group" (大 尾 象 工作 组, members Lin Yilin , Chen Shaoxiong , Liang Juhui , Xu Tan , Zheng Guogu , Zhang Haier and Hou Hanru ). However, the work of this art movement was also hindered to a large extent by the authorities.

"In autumn 2000, the curator and art critic Feng Boyi organized the groundbreaking [...] exhibition Fuck Off together with the artist Ai Weiwei . It was an unofficial addition to the 3rd Shanghai Biennale, which was more in keeping with the regime, and is now regarded as the starting point for a new art and exhibition Understanding of artists at the beginning of the new millennium in Shanghai. The exhibition venue for the extremely provocative, sometimes aggressive works of art by a total of 46 young and in part already established Chinese artists was the 900 m 2 Eastlink Gallery , which was opened a year earlier in the then new gallery and gallery The bohemian M50 district (named after the address, 50 Moganshan Lu) and a warehouse on West Suzhou River Road. The Chinese exhibition title means something like "A non-cooperative attitude", and the English name was "Fuck Off" "." *

Nevertheless, numerous Chinese artists achieved international recognition and were invited to the Kassel Documenta around 2000 . This is not least due to the committed work of museum curators such as Hou Hanru who work outside the People's Republic . But also domestic curators like Gao Minglu spread the idea of art as a powerful force within Chinese culture.

Cao Yingyi (* 1939 in Tongling / Anhui Province) is currently one of the most famous painters in his country . In American art circles he is referred to as the "impressionist of Chinese ink and watercolor painting". In the early 1990s, Cao Yingyi received the title of honorary citizen of the two American cities of Columbia City (South Carolina) and Bethlehem (Pennsylvania). September 24, 1993 was declared Cao Yingyi Day in Bethlehem City. Cao Yingyi had numerous well-known teachers, among others he was a student of the great Chinese painter Fu Baoshi (1904-65), who is now counted among the most important painters in China in the 20th century. Cao Yingyi came into contact with Western painting as a young man. He was influenced by both French impressionism and socially critical artists such as Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) and the Belgian artist Frans Masereel (1889-1972), who were very well known in Chinese art circles in the early 1930s . In addition to Cao Yingyi's impressive landscape paintings, the lyrical quality of which earned the painter the title of "poet of Chinese ink painting" (today one even speaks of the "Cao style" in China), mention should also be made of the Dunhuang series, pictures that are part of the Chinese art world occupy a special position and can be regarded as an extraordinary rarity. With his calligraphy, Cao Yingyi - succeeding the great painter Qi Baishi (1863-1957) - is considered the leading Chinese painter of the cancer motif in China. Cao Yingyi was the guest of honor in Cologne's China Year 2012.

The most important contemporary artists include Cao Yingyi (领 英; * 1939), Ai Xuan (* 1947), Wáng Guǎngyì (王广义; * 1956), Xú Bīng (徐冰; * 1955), Wu Shan Zhuan (* 1960), Huáng Yǒng Pīng (黄永 砯, * 1954), Wéndá Gǔ (谷 文 達, * 1956), Lǚ Shèngzhōng (吕 胜 中, * 1952) and Mǎ Qīngyún (马青云, * 1965).

See also

literature

- Richard M. Barnhart et al. a .: Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting . Yale 2002, ISBN 0-300-09447-7 .

- Herbert Butz: literary painter of the Ming period , in: Lothar Ledderose (ed.): Palace Museum Beijing. Treasures from the Forbidden City . Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-458-14266-5 , pp. 217ff.

- James Cahill : The Chinese Painting . Geneva 1960.

- James Cahill: Chinese Painting 11. – 14. Century . Hanover 1961.

- Gérard A. Goodrow: Crossing China. Land of the Rising Art Scene , Cologne: Daab 2014, ISBN 978-3-942597-12-8 .

- Emmanuelle Lesbre, Jianlong Liu: La Peinture Chinoise. Hazan, Paris, 2005, ISBN 978-2-85025-922-7 .

- Werner Speiser u. a .: Chinese art - painting, calligraphy , stone rubbing , woodcuts . Herrsching 1974.

Web links

- Cornell University website with examples of Song Dynasty painting

- Chinese painting motifs and application examples

- A Pure and Remote View: Visualizing Early Chinese Landscape Painting : Series of video lectures by James Cahill.

- Gazing Into The Past - Scenes From Later Chinese & Japanese Painting : Series of video lectures by James Cahill.