Zen

| Zen | |

|---|---|

| Chinese name | |

| Long characters | 禪 |

| Abbreviation | 禅 |

| Pinyin (Mandarin) | Chan |

| Jyutping (Cantonese) | Sim 4 |

| Vietnamese name | |

| Quốc Ngữ | Thiền |

| Hán tự | 禪 |

| Korean name | |

| Hangeul | 선 |

| Hanja | 禪 |

| Revised Romanization | Seon |

| Japanese name | |

| Kanji | 禅 |

| Rōmaji | Zen |

Zen Buddhism or Zen (Chinese Chan , Korean Seon , Vietnamese Thiền ) [ zɛn , also t͜sɛn ] is a movement or line of Mahayana Buddhism that emerged in China from around the 5th century of the Christian era and was significantly influenced by Daoism . The Chinese term Chan ( Chinese 禪 , Pinyin Chán ) comes from the Sanskrit word Dhyana (ध्यान), which was translated into Chinese as Chan'na ( 禪 那 , Chán'nà ). Dhyana means something like "state of meditative immersion", which refers to the basic characteristic of this Buddhist current, which is therefore also referred to as meditation Buddhism.

Chan Buddhism spread to the neighboring countries of China through monks . A Korean ( Seon , korean. 선) and a Vietnamese (Thiền) tradition emerged.

From the 12th century onwards, Chan came to Japan , where it was given a new form as Zen . In modern times this came to the West in a new interpretation . Most of the Zen terminology used in Europe and the USA therefore comes from Japanese. But Korean, Vietnamese and Chinese schools have also recently gained influence in Western cultures.

Self-image

Zen Buddhism can be characterized by the following lines since the Song era :

"1. A special tradition outside of the scriptures,

2. independent of words and characters:

3. show the human heart directly, -

4. look at (one's own) nature and become Buddha. "

The four verses were first ascribed together as a stanza in 1108 in the work Zǔtíng Shìyuàn ( 祖庭 事 苑 ) by Mùān Shànqīng ( 睦 庵 善卿 ) Bodhidharma . The lines appeared singly or in various combinations earlier in Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. The attribution to the legendary founder figure is seen today as a definition of the self-image after a phase of dispute over direction.

The fourth verse reads in Japanese as " kenshō jōbutsu" ( 見 性 成佛 ). The programmatic statement is considered characteristic of Chan / Zen, but appears for the first time earlier (around 500) in a commentary ( 大 般 涅槃經 集解 ) on the Nirvana Sutra .

Teaching

It is often said that Zen offers “nothing”: no teaching , no secret, no answers. In a kōan ( 公案 ) the Zen master Ikkyū Sōjun ( 一 休 宗 純 ) speaks to a desperate person:

"I would like to offer something

to help you,

but in Zen we have nothing at all."

It means living life - in all its fullness. Direct access to this simplest of everything is, however, blocked to the intellectual being - it seems as if the never-silent voice of thoughts is blocking him with stubborn ideas and judgmental conceptions. The attachment to the illusion of an I of every individual only causes new suffering (dukkha) over and over again . Zen can resolve this confusion - in the end, one can even eat when one is hungry , and sleep when one is tired . Zen is nothing special . It has no goal.

The characterization that Zen offers “nothing” is often expressed by Zen masters to their students in order to deprive them of the illusion that Zen offers knowledge that can be acquired or that it can be something “useful”. On another level, the opposite is apparently also being asserted: Zen offers the “whole universe”, since it includes the abolition of the separation of the inner world and the outer world, that is, “everything”.

Zen eludes reason and is often perceived as irrational, also because it fundamentally opposes any conceptual definition. The seemingly mysterious aspect of Zen, however, stems solely from the paradoxes brought about by trying to speak about Zen. Zen always aims at the experience and action in the present moment and in this way includes feeling, thinking, feeling, etc.

Zen also has philosophical and religious aspects and teachings that have evolved over time, for example in the Sōtō or Rinzai school. These can of course be described in words - even if they are not absolutely necessary for the subjective experience of Zen.

practice

The practice consists on the one hand of zazen (from Japanese : Za- [sitting]; Zen- [contemplation]), sitting in contemplation on a cushion. In the outer posture, the legs are crossed like in the lotus position in yoga. The back is straight but completely relaxed and the hands are relaxed, with the tips of the thumbs touching each other. The eyes remain half open, the gaze remains relaxed, without wandering, lowered to the ground. For beginners, easier sitting styles are also recommended, such as the half lotus seat (Hanka-Fuza), the so-called Burmese seat or the heel seat ( Seiza ).

Another equally important part of Zen practice is focusing on everyday life . It just means that you are totally focused on the activity you are doing right now, without thinking about anything. Both exercises complement each other and are intended to calm the mind or to contain the "flood of thoughts" that constantly overwhelms you.

"When our mind finds peace, it

disappears by itself."

Primacy of practice

Zen is the pathless path , the goalless gate . According to the teaching, the great wisdom ( prajna ) underlying Zen does not need to be sought, it is always there. If the seeker were able to simply give up their permanent efforts to maintain the illusion of the existence of an "I", Prajna would occur immediately.

Realistically, however, following the Zen path is one of the more difficult things that can be done in a human life. The willingness to give up their self-centered thinking and ultimately of the self is required of the students . The practice path usually takes several years before the first difficulties are overcome. The teachers named Rōshi are helpful here . However, the path is always also the goal; in practice, fulfillment is always present.

The primary task of the student is the continued, complete and conscious awareness of the present moment, a complete mindfulness without own judgmental participation ( samadhi ). He should not only maintain this state during meditation, but if possible at every moment of his life.

"Zen is not something exciting,

but concentrating on your daily activities."

In this way the knowledge of absolute reality can come about ( satori ). The question of the meaning of life is eliminated; the contingency of one's own existence, being thrown into the world, can be accepted. Complete inner liberation is the result: there is nothing to achieve, nothing to do and nothing to own .

Methods

Over time, Zen masters have developed various techniques that help students and prevent undesirable developments. The training of attentiveness and unintentional introspection are paramount; in addition, disruptive discursive thinking is brought to an end. Zen cannot actually be taught. Only the conditions for spontaneous, intuitive insights can be improved.

The common methods of Zen practice include zazen (sitting meditation), kinhin (walking meditation), recitation (text readings), samu (concentrated activity) and working with questions called kōan. These methods are practiced particularly intensively during several days of practice periods or exams ( sesshin or retreat ). The student must at least integrate the sitting meditation into his everyday life , because Zen is by its nature always only practice.

aims

As the flood of thoughts comes to rest during the practice, the experience of silence and emptiness, Shunyata , becomes possible.

Especially in Rinzai Zen, the mystical experience of enlightenment ( Satori , Kenshō ), an often suddenly occurring experience of universal unity, i.e. H. the abolition of the subject-object opposition, the central theme. In this context, there is often talk of “awakening” and “enlightenment” (pali / Sanskrit: Bodhi ), of “becoming a Buddha”, or the realization of one's own “ Buddha-nature ”. This experience of non-duality is hardly accessible to linguistic communication and cannot be conveyed to a person without comparable experience. Usually this is only discussed with the Zen teacher.

In Sōtō-Zen, the experience of enlightenment takes a back seat. Shikantaza , “just sitting”, becomes the central concept of Zen practice . H. the unintentional, non-selective attention of the mind in zazen, without following or suppressing a thought. In Sōtō, zazen is not understood as a means to the end of the search for enlightenment, but is itself the goal and end point, which does not mean that no state of enlightenment can or must not occur during zazen or other activities. The great Kōan of Sōtō-Zen is the zazen posture itself. Central to the realization of this unintentional sitting is Hishiryō , the non-thinking , i.e. H. going beyond ordinary, categorizing thinking. Dōgen writes the following passage in Shōbōgenzō Genjokoan :

“To study the way means to study yourself.

To study yourself is to forget yourself.

To forget yourself means to become one with all existences. "

Objects of Zen practice (selection)

Keisaku ( 警策 ) is a slat-like stick with which the practitioner receives two to three blows on the shoulder muscles during long meditations in order to release tension and stay awake.

Zafu ( 座 蒲 ) is a traditional pillow for sitting meditation .

Zendō ( 禅堂 ) is a room or hall for communal Zen meditation, also known as Dōjō .

The sound of the wooden fish (Japanese mokugyo 木魚 ) signals the beginning and the end of a meditation session.

history

Zen as we know it today has been influenced and enriched by many cultures over a millennium and a half. Its beginnings can be found in 6th century China, although its roots probably go back further and influences from other Buddhist schools are also present. After Bodhidharma brought the legend in the 6th century AD the teaching of meditation Buddhism to China, where he became Chan was -Buddhismus, design influences of Daoism and Confucianism / Neo-Confucianism one. A large number of writings with poems, instructions, conversations and kōans date from this period. For this reason, many terms and personal names are found today in both Chinese and Japanese pronunciation. The transfer of the teachings by Eisai and Dōgen to Japan in the 12th and 13th centuries, in turn, contributed to the change in Zen, through general Japanese influences, but also mikkyō and local religions.

In the 19th and especially in the 20th century, the Zen schools in Japan went through rapid changes. A new form of Zen was established by laypeople. This reached Europe and America and was also inculturated and expanded. Since the 20th century even some Christian monks and laypeople have turned to meditation and Zen, through which, partly supported by authorized Zen teachers who remained connected to Christianity, the so-called "Christian Zen" arose.

origin

According to legend, the historical Buddha Siddhartha Gautama is said to have gathered a crowd of disciples around him after the famous sermon on the Geierberg, who wanted to hear his presentation of the Dharma . Instead of speaking he silently held up a flower. Only his disciple Mahakashyapa understood this gesture as a central point of the Buddha's teaching and smiled. He had suddenly come to enlightenment. This is supposed to be the first transmission of the wordless teaching from heart-mind to heart-mind (Japanese Ishin Denshin ).

Since this insight of the Kāshyapa cannot be recorded in writing, it has been transmitted personally from teacher to student ever since. One speaks of so-called Dharma lines (i.e. roughly: teaching directions).

According to legend, this direct tradition continued through 27 Indian masters to Bodhidharma, who is said to have brought the teaching to China and thus became the first patriarch of Chan .

- Bodhidharma ( Skt. बोधिधर्म, Chinese Damo 達摩 , Japanese Daruma 達磨 ) (* around 440 to 528)

- Dàzǔ Huìkě ( 太祖 慧 可 , Japanese Daiso Eka ) (487–593)

- Jiànzhì Sēngcàn ( 鑑 智 僧 燦 , Japanese Kanchi Sōsan ) (*? To 606)

- Dàyī Dàoxìn ( 大 毉 道 信 , Japanese Dai'i Dōshin ) (580–651)

- Dàmǎn Hóngrěn ( 大 滿 弘忍 , Japanese Dai'man Konin ) (601–674)

- Dàjiàn Huìnéng ( 大 鑒 慧能 , Japanese Daikan Enō ) (638–713)

After the 6th Patriarch, the line divides into different schools. For China around 950 one speaks of the 5 houses :

- Caodong ( 曹洞 ) (Japanese Sōtō ) brought to Japan by Dōgen Zenji

- Fayan ( 法眼 ) (Japanese Hōgen )

- Guiyang ( Chinese 潙 仰 ) ( Japanese Igyō )

- Linji Yixuan ( 臨 済 ) (Japanese Rinzai ) brought to Japan by Eisai Zenji

- Yunmen ( 雲 門 ) (Japanese ummon )

As a result, other schools have emerged up to the present day, including the three Zen schools in Japan that still exist today:

and the modern:

Japan

Despite the great importance of Zen (Chan) in China and the closeness to the government of many monasteries there, no Zen tradition line was brought to Japan as a school during the Nara period (710–794). Later attempts had no historical consequences until the 12th century.

The term Zenji (Zen master) appeared in the first writings as early as the Nara period : it mostly describes practitioners of Buddhist rituals (mostly ascetic practices, meditation, recitations, etc.) who were not authorized by the imperial government and were not officially ordained. ). It was believed that through these rituals, practitioners acquired great but ambivalent powers.

From the Kamakura period onwards , Zen was able to gain a foothold and the main schools Sōtō , Rinzai and Ōbaku emerged.

After the Meiji Restoration , Buddhism was briefly persecuted in Japan and abandoned by the new policy in favor of a renativistic Shinto as the religion of those in power. In times of ever more rapid social, cultural and social change, the shin-bukkyō , the new Buddhism, emerged. B. was socially active. The seclusion of the monasteries also loosened, so lay groups were taught zazen and the teaching of Zen.

Modern

Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki became an important Japanese author of books on Zen Buddhism in its modern form. After completing his Zen studies in 1897, Suzuki followed Paul Carus' call to America and became his personal assistant. In the 1960s, Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki had an influence on the humanist movement at the Esalen Institute (Human Potential Movement, Claudio Naranjo ) through his student Alan Watts and Charlotte Selver . Philip Kapleau also first learned from Suzuki, but later placed much more emphasis on Zen practice.

In 1958 the Japanese Suzuki Shunryū went to the USA in San Francisco and took over the management of the Japanese Sōtō community there. He founded the first Zen monastery outside of Asia. One popular book was Zen Mind - Beginners Mind .

Zen in the west

In modern times the spread of Zen in Japan has decreased, but the number of followers in the western world is increasing . Zen courses for executives from business and politics were created in the USA, Germany and Switzerland. The religious scholar Michael von Brück observes: "Zen in the West is in the process of a creative awakening that is multifaceted and reveals open organizational contours".

In the 20th century a lively exchange between Eastern Zen and the West began. In 1948 the German philosopher Eugen Herrigel published his bestseller Zen in the Art of Archery , a classic of Western Zen literature with high editions in the 20th century. In 1956 the work was even published in Japanese. Many intellectuals in post-war Germany were “fascinated by Zen” after reading this book. Karlfried Graf Dürckheim , who worked in Japan between 1939 and 1945, promoted the connection between Zen and art as a psychologist, therapist and Zen teacher. Maria Hippius Countess Dürckheim suggested similar bridges between therapy and Zen .

Zen in connection with the churches

Favored by a lack of dogmatism, there are also connections to the Catholic Church. Mediators as religious, priests, professors and theologians are u. a .:

- Hugo Makibi Enomiya-Lassalle (1898–1990), SJ

- Willigis Jäger (1925-2020), OSB , Ko-un Roshi

- Josef Sudbrack (1925-2010), SJ

- Johannes Kopp (1927-2016), SAC , Ho-un-Ken Roshi

- Peter Lengsfeld (1930-2009), Chô-un-Ken Roshi

- Willi Massa (1931-2001), SVD

- Niklaus Brantschen (* 1937), SJ

- Pia Gyger (1940–2014), co-founder of the Lassalle Institute within the Lassalle House in Bad Schönbrunn

- Jakobus Kaffanke (* 1949), OSB

- Stefan Bauberger (* 1960), SJ

But the connection between Protestant theology and Zen can also be observed since the turn of the millennium. This is what u. a .:

- Doris Zölls (* 1954), with the Zen name Myô-en An, pastor and Zen master of the Zen line Empty Cloud.

The background to this encounter was the insight that Hans Waldenfels formulated in 1979 as follows: “In terms of religious history, Zen Buddhism and Christianity oppose each other as two ways of realizing a common basic religious experience.” For Hans Küng , Zen is “very much under the great program word of freedom: freedom of oneself in self-forgetfulness. Freedom from every physical and mental constraint, from every instance that wants to place itself between people and their immediate experience and enlightenment. Freedom also from Buddha, from the holy scriptures, freedom ultimately also from Zen, which is and remains the way, not the goal. Man can only come to enlightenment in full inner freedom ”. It is therefore no surprise to the Christian theologian Hans Küng, “even if Christians who feel regulated by church dogmatics, rigid rules and spiritual training right into prayer, have such content-free thinking, such objectless meditation, such happy experiences Feel emptiness as true liberation. Here you will find inner peace, greater serenity, better self-image, finer sensitivity for the whole of reality ”.

Teachings and schools of Zen in the west

Zen has spread to various schools in the West. An essential challenge and task of the Zen masters is to transform and pass on authentic Zen in a form appropriate for "Westerners".

Sōtō school

The Japanese Zen master Taisen Deshimaru Rōshi, a student of the Sōtō Zen master Kodo Sawaki Roshi, came to France in the 1960s, where he taught Zen until his death in 1982. He left behind a large student body that continues to grow today and is represented by various Zen organizations across Europe. Deshimaru founded the Association Zen Internationale (AZI) in 1970 .

Brigitte D'Ortschy was the first German Zen master and known under the name Koun-An Doru Chiko Roshi . She is considered to be the first western Zen master with students from all over the world. From 1973 she held the first sesshin in Germany with Yamada Koun Roshi and founded her own zendo in Munich- Schwabing in 1975 , which later moved to Grünwald .

Also influential is Bernard Glassman , a US Zen master who came from a Jewish family. Glassman is the initiator and manager of various social projects, including a. the Zen Peacemakers , a group of socially committed Buddhists.

Another representative of the Sōtō School is the US American and Vietnam veteran Claude AnShin Thomas . He has made a vow as a beggar and wandering monk and teaches wherever he is invited in the world. He is the founder of the Zaltho Foundation in the USA, a non-profit organization that is particularly dedicated to reconciliation work with victims of war and violence. The sister organization is the Zaltho Sangha Germany. Claude AnShin Thomas studied with Thích Nhất Hạnh for several years and was ordained in 1995 by Bernard Tetsugen Glassman Roshi as a Buddhist monk and priest in the Japanese Sōtō-Zen tradition.

The Sōtō-Zen school is currently represented in Germany u. a. by Fumon Shōju Nakagawa Roshi and Rev. L. Tenryu Tenbreul , a former disciple of Taisen Deshimaru . The Sōtō-Zen umbrella organization, the Sōtō-Zen Buddhism Europe Office , is headed by Rev. Genshu Imamura and has its headquarters in Milan .

Rinzai Zen

The Japanese Zen master Kyozan Joshu Sasaki , who has been teaching Zen in the USA since 1962, has been coming to Austria regularly since 1979 to give lectures and perform sesshins . His work and that of his students, above all the development work of Genro Seiun Osho in Vienna and southern Germany, contributed significantly to the establishment of the Rinzai -Zen school in the German-speaking area.

The Austrian Irmgard Schlögl went to Japan in 1960 to be one of the first western women to get to know authentic Zen there. In 1984 she was finally ordained a Zen nun with the name Myokyo-ni . She founded the Zen Center in London as early as 1979 and from then on worked both as a translator of important Zen writings and as a Zen teacher. A similar path with Gerta Ital from Germany. In 1963 she was the first western woman to be allowed to live and meditate in a Japanese Zen monastery for seven months on an equal footing with the monks. The literary output of this time was her book: The Master the Monks and I, a woman in the Zen Buddhist monastery , deep impressions that were to shape the image of Japanese Zen in the West. Further publications on Zen by her, combined with committed teaching activities, followed.

One of the mainstays of Rinzai Zen in the 21st century is the Bodaisan Shoboji Zen Center in Dinkelscherben , overseen by the Japanese Zen master Hozumi Gensho Roshi and managed by the German Zen master Dorin Genpo Zenji until 2017 , which has officially been the branch temple of the Myōshin-ji , a temple of the great Rinzai traditions in Japan, is believed to be. Dorin Genpo Zenji also looked after the Hakuin-Zen-Gemeinschaft Deutschland eV until 2017

Shōdō Harada Roshi has been a Zen master since 1982 at Sōgen-ji Monastery in Okayama, where he mainly teaches foreign students. He has set up various centers ( One Drop Zendo ) in Europe, India and the USA.

Other schools: Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese tradition

In the West, Zen does not only focus on its Japanese form. The Chinese (Chán), Korean (Seon) and Vietnamese (Thiền) traditions have also found important representatives, followers and lively practice groups there:

The Korean Zen master Seung Sahn founded the Kwan Um Zen School in the USA in 1970 , which has since established numerous centers there and in Europe, with the main European temple in Berlin.

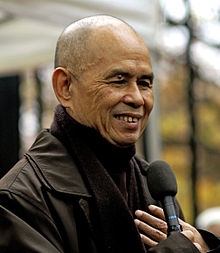

An important contemporary Dharma teacher is the Vietnamese Thích Nhất Hạnh , who combines Zen ( Mahayana ) with elements of Theravada Buddhism ( Vipassana ). It is "interreligious and propagates a non-violent life in mindfulness, ecological awareness and social commitment".

Forms of Reception in the West

“Hyphenated Zen” and instrumentalization

Under the cultural influences in the USA and in Europe, Zen is practiced differently than in Japan and can thus create a new z. B. gain instrumentalized meaning. Stephan Schuhmacher sees such changes as the danger of Zen decline in the West: “The still young history of Zen in the West is overshadowed by guru hype, commercial interests, sectarian disputes and some scandals and scandals. ... These germs of decay find a particularly beneficial climate in the West ”. The West receives Zen, “[this] tradition that essentially defies reification”, with a “tendency towards instrumentalization”. Zen is "misunderstood as a mere method and misused as a means to an end".

The ramifications of Zen in the West have several dimensions:

- therapeutic: Zen as a panacea for neuroses and depression. Zen then becomes "a kind of spiritual Valium"

- performance enhancing: Zen has concentrative energy that enables maximum performance

- Increasing attractiveness: Christian churches as old institutions are attracting new attention for themselves through the offer of eastern meditation paths and the exoticism associated with them.

Zen as such is not enough for the West; Zen is enriched there with further goals. According to Koun-An Doru Chiko , Zen in the West is shaped by various secondary goals . Zen loses its own character and becomes this -and-that Zen , hyphenated Zen . Examples are:

- Business zen

- Therapy zen

- Wellness zen

- Street zen

- Ecology zen.

Stephan Schuhmacher therefore notes with concern: Western Zen centers with their programs often degenerate into a “spiritual Club Mediterrané” and asks: “Where is the Zen of the patriarchs?” The “Zen of the patriarchs” here means a Zen, that preserves the “essence”, the spirit of the founding fathers, without diluting it with secondary goals and personal or institutional interests, and producing a kind of “Zen light” that lacks the profound transformative power of the Zen of the patriarchs.

Naked Zen, freed from Buddhism and external forms

Willigis Jäger questions a Zen that transfers the religious, cultural, ritual superstructure of the monastic East Asian Zen schools to the West. Jäger sees not the return to the East, but the consistent turning to the West in the form of courageous inculturation as a necessity and the only feasible path: “Only bare Zen has a chance in the West. Buddhism as a religion is unlikely to gain ground in the West, but Zen does. Zen will have to inculturate. "

For hunters, however, this means consciously turning away from the monastic forms of Eastern Zen and turning to Western lay Zen : “Much of what has developed as a monastic form in the Zen monasteries in the East will be omitted. It comes to a 'lay Zen'. ... Rituals, clothing, sound instruments that have been used in monasteries throughout history play an important role and often cover up the essentials. Buddhist monk robes, the style of a sesshin, incense sticks etc. are considered very important in some groups. The tendency towards external forms is a beginner's disease. Naked Zen is an immutable stream that will change its external structure in the West, just as it changed in China when it encountered Taoism. His essence will not be falsified. "

Christian zen

In the Christian churches there are tendencies to interpret what is foreign in Zen, so that so-called “Christian Zen” developed. Ursula Baatz sees an alternative to this in understanding the encounter between Christianity and Zen Buddhism not as a “union” of spiritual paths that ultimately lead to the same thing, but as an encounter and relationship in which both are mutually enriched and each is also changed but without becoming "one". "Religious bilingualism" is what Baatz calls this, referring to schools of thought that arose, among other things, from the encounter between Zen and Christianity in an intercultural context . Then one can no longer speak of “Christian Zen”, but one can speak of a Christian practicing Zen and thus gaining additional experience in another religious practice.

Zen and culture

The American Edward Espe Brown combines the art of cooking with Zen and gives Zen cooking classes.

The Swiss Helmut Brinker dealt with the contacts between Zen and the visual arts .

The film How to Cook Your Life by Doris Dörrie , 2007 turned with the Buddhist Center Scheibbs , provides a bridge to important insights of Zen ago.

Literary bridges to Zen were also created: Gammler, Zen und Hohe Berge is the German title of a novel published in 1958 by Jack Kerouac .

literature

Philosophy Bibliography : Zen - Additional Bibliography on the Subject

- Classical works

- Baek-Un: Jikji. Korean Zen Buddhism Collection. Frankfurt 2010. ISBN 9783936018974

- Dôgen Zenji: Shôbôgenzô. The treasure of the true Dharma. Complete edition. Angkor Verlag, Frankfurt 2008, ISBN 9783936018585

- Eihei Dogen Zenji: Shobogenzo - Selected Writings. Different philosophizing from Zen. Bilingual edition. Translated, explained and edited by Ryōsuke Ōhashi and Rolf Elberfeld , Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-7728-2390-9 .

- Source collections

- Karlfried Graf Dürckheim : Wonderful cat and other Zen texts. 10th ed., Barth u. a. 1994, ISBN 3-502-67159-1 .

- Paul Reps (Ed.): Without words - without silence: 101 Zen stories and other Zen texts from 4 millennia. 7th edition, Barth, Bern a. a. 1989, ISBN 3-502-64502-7 .

- New edition: 101 Zen stories , Patmos-Verlag, Düsseldorf 2002 ISBN 3-491-45022-5 .

- Bodhidharma's Teaching of Zen: Early Chinese Zen Texts. Theseus-Verlag, Zurich / Munich 1990, ISBN 3-85936-034-5 .

- Popular literature

- Shunryu Suzuki : Zen Mind Beginner Mind. Teaching in Zen meditation. Theseus, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-95883-148-3 .

- Daisetz T. Suzuki : The Great Liberation: Introduction to Zen Buddhism. 20th edition, Barth, Munich a. a. 2003, ISBN 3-502-67594-5 .

- Alan Watts : From the Spirit of Zen. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-518-37788-4 .

- Ingeborg Y. Wendt: Zen, Japan and the West . List, Munich 1961.

- Alfred Binder : The Myth of Zen. Alibri Verlag, Aschaffenburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-86569-057-9 .

- Specialist literature

- Harry Mishō Teske: Zen Buddhism Step by Step. Philipp Reclam jun., Ditzingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-15-011153-6 .

- Rolf Elberfeld : Zen. 100 pages. Philipp Reclam jun., Ditzingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-15-020437-5 .

- Rolf Elberfeld: Phenomenology of Time in Buddhism. Methods of intercultural philosophizing. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 978-3-7728-2227-8 (habilitation thesis with a focus on the famous text "Uji" by the Zen Buddhist Dogen)

- Bernard Faure: Chan Insights and Oversights. An Epistemological Critique of the Chan Tradition. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey 1993, ISBN 0-691-06948-4

- Byung-Chul Han : Philosophy of Zen Buddhism. Reclam, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 978-3-15-018185-0

- James W. Heisig and John C. Maraldo (editors): Rude Awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto School, & the Question of Nationalism (Nanzan Studies in Religion and Culture). University of Hawaii Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8248-1735-4

- Brian A. Victoria: Zen, Nationalism and War. Theseus-Verlag, Berlin 1999. ISBN 3-89620-132-8

- Michael von Brück: Zen, History and Practice. C. H. Beck knowledge. ISBN 978-3-406-50844-8

- Katsuki Sekida: Zen Training. Practice, methods, background. 2nd edition, ISBN 978-3-451-05936-0 , Herder, Freiburg 2009

- Tools

- Michael S. Diener: The Lexicon of Zen. Goldmann, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-442-12666-5

- Lexicon of the Eastern Wisdom Teachings. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-96136-X

- Stefan Winter: Zen. Bibliography by subject area. Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 2003, ISBN 3-631-51221-X

- James L. Gardner: Zen Buddhism. A classified bibliography of Western-language publications through 1990. Wings of Fire Press, Salt Lake City, Utah 1991, ISBN 1-879222-02-7 , ISBN 1-879222-03-5

Web links

- The Zen Site (in English)

- Shigenori Nagatomo: Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . (in English)

- On the history of Zen Buddhism by Bernhard Scheid from the Institute for the Cultural and Spiritual History of Asia at the Austrian Academy of Sciences

- Prof. Carl-Albert Keller: Silence and emptiness in Zen Buddhism , studies

Individual evidence

- ↑ Heinrich Dumoulin : History of Zen Buddhism. Volume I: India and China. P. 83

- ↑ Albert Welter: A Special Transmission. An essay, accessed February 27, 2013

- ↑ Isshū Miura, Ruth Fuller Sasaki: Zen Dust. New York 1966, p. 229.

- ↑ Michael S. Diener: The Lexicon of Zen. P. 244; Lexicon of the Eastern Wisdom Teachings. P. 471 f.

- ↑ Michael von Brück : Zen. History and Practice , Munich 2007, 2nd edition, p. 121, Knowledge series in the Beck'schen series, ISBN 978-3-406-50844-8

- ↑ a b Michael von Brück: Zen. History and Practice , Munich 2007, 2nd edition, p. 122, ISBN 978-3-406-50844-8

- ^ The 43rd edition was published in Frankfurt 2003, ISBN 3-502-61115-7

- ↑ Michael von Brück: Zen. History and Practice , Munich 2007, 2nd edition, p. 123, ISBN 978-3-406-50844-8

- ↑ for example Hans Waldenfels in: The Dialogue Between Buddhism and Christianity. Challenge for European Christians, lecture 1979 in the Catholic Academy Menschen, lecture on Spirit and Life , accessed on March 15, 2019

- ↑ Hans Küng and Heinz Bechert , Christianity and World Religions. Buddhism, GTB Sachbuch 781, Gütersloher Verlag, Gütersloher 1990, 2nd edition, p. 204, ISBN 3 579 00781 5

- ^ Website of the Johanneshof ( Memento of the original from August 13, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed June 15, 2015

- ↑ Gerta Ital: The Master the Monks and I, a Woman in a Zen Buddhist Monastery , 1966, Otto Wilhelm Barth Verlag; further editions by Scherz Verlag

- ↑ a b Stephan Schuhmacher: Zen , Munich 2001, p. 102, ISBN 3-7205-2192-3

- ↑ Koun-An Doru Chiko, cit. in: Stephan Schuhmacher: Zen , Munich 2001, p. 102

- ↑ Stephan Schuhmacher: Zen , Munich 2001, p. 103

- ↑ Willigis Jäger, quoted by Sabine Hübner, texts by the Roshis Yamada Koun and Willigis Jäger ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed March 22, 2015

- ↑ Willigis Jäger, Magazin des Frankfurter Ring 2004 ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed March 22, 2015

- ↑ Antje Schrupp, enlightenment meets resurrection. Ursula Baatz analyzes the relationship between Christianity and Zen Buddhism www.bzw-weitermachen.de , accessed on March 15, 2019