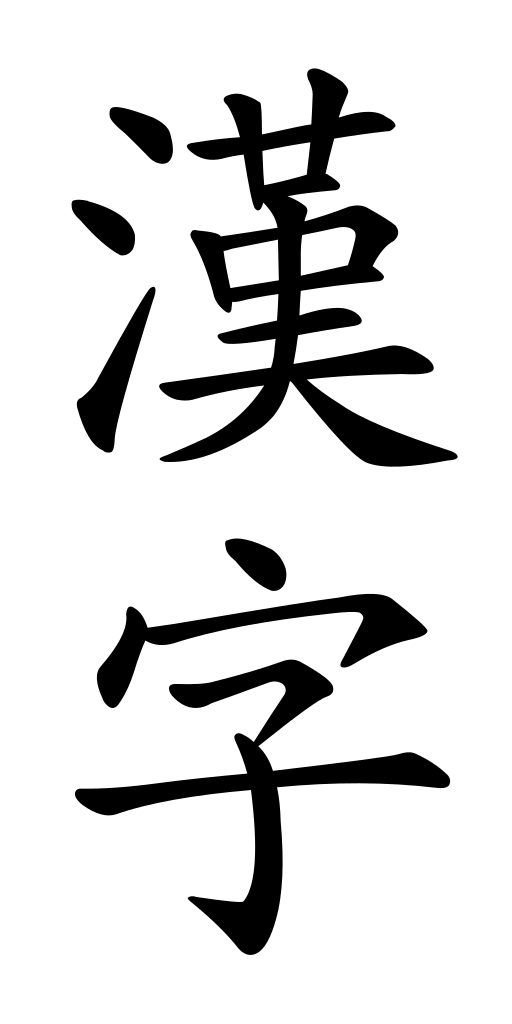

Kanji

Kanji [ kaɴdʑi ] are the characters of Chinese origin used in the Japanese writing tradition . The word Kanji is written in Chinese characters as 漢字 , in Hiragana script as か ん じ . The characters that were created exclusively in Japan are called Kokuji - 国 字'National characters' - or Wasei kanji - 和 製 漢字'Japanese characters' - and are part of the Japanese Kanji writing system. Like all others, these characters are put together by a mosaic-like composition of Chinese script elements. The use of the Kanji - Shinjitai - "slightly modified" today by the writing reform in Japan compared to China, are ultimately graphic or historical varieties of the same characters. With a few exceptions , they differ only slightly from the general standard spellings in today's country of origin China - short characters - or Taiwan, Hong Kong , Macau - traditional characters .

| Kanji | ||

|---|---|---|

| Font | Logographic | |

| languages | Japanese | |

| Usage time | since approx. 500 AD | |

| Officially in |

|

|

| ancestry |

Chinese characters Kanji |

|

| Derived |

Hiragana Katakana |

|

| relative | Hanzi , Hanja , Chữ Nôm | |

| Unicode block | U + 4E00… U + 9FC6 U + 3400… U + 4DBF U + 20000… U + 2A6DF U + 2A700..U + 2B734 U + 2B740..U + 2B81D U + 2B820..U + 2CEA1 |

|

| ISO 15924 | Hani Japan (Kanji, Hiragana, Katakana) |

|

use

Integrated into modern Japanese syllabary texts, Kanji today denote nouns or word stems of verbs and adjectives .

The earliest Japanese texts - Kanbun - are written entirely in Kanji. A Kanji could stand for a Japanese word, (regardless of meaning) for a Japanese language sound ("reading" of this Kanji) or for a small rebus .

etymology

The logogram 字 in the meaning of “characters” is implemented in Chinese according to Pinyin as zì phonetically, in Japanese as ji ; d. H. The word ji is ultimately a Chinese loan word - in Japanese , although it is hardly perceived as such today.

The Chinese character 漢 - Pinyin hàn - refers to the historical Han dynasty , which shaped Chinese identity. It appears in Japanese as kan . Kanji means "characters of the Han people".

Chinese characters

At the time of the Chinese Han dynasty , the first dictionary of signs - the Shuowen Jiezi - was created after the Chinese script had already been standardized in the previous Qin dynasty .

Differences between Japanese and Chinese characters

Although the Japanese Kanji originated from these characters, today there are some differences between them - Hanzi and Kanji.

- On the one hand, not all characters were adopted, on the other hand, some characters, the so-called kokuji , were developed in Japan.

- The Chinese characters have been simplified in both China and Japan over time, the last time in Japan in 1946. However, these simplifications were not coordinated between the individual countries, which is why a whole series of characters nowadays exists in three variants, as traditional characters ( Taiwan , Hong Kong , Macau , Korea ), abbreviations ( People's Republic of China , Malaysia , Singapore ) and as a Japanese variant ( Shinjitai ) .

- The pronunciation is different, sometimes there is agreement.

- The meanings of the same characters sometimes differ from each other due to historical developments in their own country.

- While in Chinese all words, including grammatical particles and foreign words, are written with Chinese characters, in Japanese only meaningful elements such as nouns and stems of verbs and adjectives are written in Kanji, the rest of the Morsch characters Hiragana and Katakana take over .

history

The oldest evidence of the use of Chinese characters in Japan are engravings on bronze swords such as the Inariyama sword or the seven-armed sword , which were found in barrows ( kofun ) from the 3rd to 5th centuries AD. Japan is also mentioned in 3rd century Chinese sources. The oldest Chinese characters found in Japan date back to 57 and can be found on the golden seal of Na .

When the first scholars and books from China and Korea came to Japan and established the written culture there, is not exactly documented. It is said in Japanese legends that a Korean scholar by the name of Wani ( 王仁 , Kor. 왕인 Wang-In , Chin. Wángrén ) who worked in Baekje brought the Chinese characters to Japan in the late 4th century. He was invited to the court of the Yamato Empire to teach Confucianism , and in the process brought the Chinese books Analects of Confucius and the Thousand Sign Classic to Japan. Wani is mentioned in the historical records Kojiki and Nihon Shoki . Whether Wani was really alive or just a fictional person is just as uncertain as the correctness of the dates. The version of the thousand-character classic known today was created during the reign of Emperor Liang Wu Di (502-549).

Some scholars believe it is possible that Chinese works found their way to Japan as early as the 3rd century. What is certain is that by the 5th century AD at the latest, the Kanji were imported in several waves from different parts of China. So the first written texts in Japan were written in Chinese, including those by Japanese scholars. The Japanese term for classical Chinese literature is Kanbun .

The attempt of the Yamato court to create an administration based on the Chinese model based on literary officials failed, however, and the offices remained in the hands of the old noble clans (Uji). The Chinese classics nevertheless remained an important basis of the Japanese state. A method was developed to add small annotations to the Chinese classics so that Chinese texts could be read in Japanese. In particular, the characters have to be read in a different order, since the verb comes second in Chinese (SVO) and at the end in Japanese sentences.

In the next step, the Chinese characters were arranged in Japanese syntax in order to write Japanese sentences. The characters were initially read exclusively in Chinese, with an adaptation to Japanese phonetics , the origin of today's On reading . At the same time, there was a transition to writing existing Japanese words with Chinese characters, which is why many characters were given a second reading, the Kun reading . In order to write the conjugation endings in Japanese verbs that Chinese does not know, individual characters were only used phonetically and lost their meaning. From these so-called Man'yōgana the today's syllabic scripts Hiragana and Katakana developed .

There were no kanji for some Japanese terms. In Japan, the island nation, fishing played a bigger role than in China, and many fish in particular lacked characters. In Japan, a number of characters were created according to Chinese rules, more than half of which are names for fish.

Kun-reading of the Kanji was not standardized in the Meiji period . The characters could be associated with certain words according to personal preferences. It was not until the font reform of 1900 that standards were set here. Another development of the Meiji period was the introduction of compulsory primary education.

After the Second World War (the number of "for everyday common character" from the Ministry of Education in 1850 and first in 1981 to 1945 was Tōyō - or Jōyō -Kanji ) determined that in the school are taught. A new Jōyō Kanji list with 2,136 characters has been in effect since 2010, in which 196 new Kanji were added and five (mainly those for historical measures) were removed from the old list. Official texts and many newspapers limit themselves to these signs and reproduce all other terms in Cana. There are also more than 900 so-called Jinmeiyō Kanji , which are only official for use in Japanese proper names.

The Kanji basically correspond to the traditional Chinese characters . Some characters were simplified with the Tōyō reform in a similar way to the abbreviations in the Chinese writing reform of 1955 .

In modern Japanese, the Kanji are used to write nouns and the stems of adjectives and verbs. Particles, conjunctions and grammatical endings (Okurigana) are written in Hiragana. Onomatopoietic expressions and foreign words ( Gairaigo , 外来 語 ) are written in katakana, the former sometimes also in hiragana.

Some (non-Chinese) foreign words, some of which date back to the 16th century, such as tabako ( 煙草 or 莨 , “tobacco”) or tempura ( 天婦羅 or 天 麩 羅 ), also have a historical spelling in Kanji, the either according to meaning, as in tobacco , or phonetically, as in tempura . These spellings are known as Ateji ( 当 て 字 ). Nowadays these foreign words are often written in hiragana : not in katakana , because they are no longer perceived as foreign words, and not in kanji because the Kanji writing is too complicated.

Due to the strong Chinese influence on Korea , Kanji (Kor. Hanja ) were traditionally also used in Korea, but since the Kabo reform at the end of the 19th century these have largely been replaced by the Hangeul characters.

Systematization

The Buddhist teacher Xu Shen in his work Shuowen Jiezi around 100 AD divided the Chinese characters into six categories (Japanese 六 書 rikusho ).

The six categories

Pictograms

| Example of a pictogram - "horse" | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oracle bones | Bronze inscription | Great seal script | Small seal script | Chancellery | Rule script | |

The pictograms ( 象形文字 shōkeimoji ) are graphic representations of the objects they represent. This derivation was still very clearly recognizable in the old seal script , but it can also be understood in the more abstract modern scripts. For example, the character 門 represents a gate, 木 a tree, 人 a person, 女 a woman, etc.

Ideograms

In order to represent more abstract terms, simple symbols, so-called indicators or ideograms (Japanese 指 事 文字 shijimoji ) were used.

Examples are 上 "above" and 下 "below", or 回 "turn".

Logograms

More complex are the logograms ( 会意 文字 kaiimoji ), combined pictograms or ideograms that give a new meaning. A typical example is the combination of 日 "sun" and 月 "moon", which result in the sign 明 meaning "bright". Another is the character for “mountain pass” 峠 , which was formed from 山 “mountain”, “above” and “below”, or the characters for 林 “grove” and 森 “forest”, which are made up of doubling or tripling the character 木 "Tree" were formed.

These compositions are not always clear. For example, it happens that two characters are combined in different ways and then have different meanings. An example: The characters 心 "heart" and 亡 "die" are combined vertically to form the sign 忘 "forgotten" and horizontally to form the sign 忙 "busy".

Phonograms

These first three categories create the impression that the Chinese script and thus the Kanji are symbolic scripts and that the meaning is derived from the shape of the characters. In fact, the purely pictorial representation was not enough to represent all the terms required, and less than 20% of the characters used today belong to one of the first three categories. Instead, the vast majority of Chinese characters belong to the following fourth category, which is something like the standard, while the others are exceptions.

The phonograms , also known as phonetic ideograms ( 形 声 文字 keiseimoji ), can be split into two parts, a significant , which gives an indication of the meaning, and a phonetic , which refers to the pronunciation. Characters can be divided both horizontally and vertically. In most cases, the significant is on the left or above, the phonetic is on the right or below.

For example, in order to get characters for the numerous different tree species, the signifier 木 "tree" on the left side was combined with a second character on the right side, which was pronounced in a similar way to the tree species. This is how the characters 桜 “cherry”, 梅 “plum”, 杏 “apricot” and 松 “pine” were created. The significant can also have a figurative meaning, in the case of the tree for example “thing made of wood”, for example a shelf 棚 or a loom 機 .

At the time of the Han dynasty , characters that had the same phonetic 寺 ( 詩 , 持 , 時 , 侍 , 待 ) on the right side were also pronounced the same in classical Chinese. In part, this has survived into today's Japanese, but there have been numerous sound shifts and other changes, which is why this rule no longer applies in modern Japanese. For example, the five characters 寺 , 詩 , 持 , 時 , 侍 are all read in Sino-Japanese ji or shi , but 待 is read as tai .

Derivatives

The category of derivatives ( 転 注 文字 tenchūmoji ) is rather vaguely defined. These are characters which, in addition to their original meaning, have received other meanings associated with this and are also pronounced differently in the new meaning. The use of many characters has completely shifted and the original meaning has been lost.

An example from the group is the character 楽 , which firstly means “music” (gaku) and secondly, derived from it, “happiness” (raku) .

Borrowings

Another group are phonetically borrowed characters ( 仮 借 文字 kashamoji ). These were created as pictograms, for example 永 for "swim". However, when a character was used for the word “eternal”, which was pronounced the same in ancient Chinese, the meaning of the character was transferred. A new phonogram was created for the word “swimming” by adding three drops of water ( 氵 ): 泳 . The same pronunciation of both characters has been preserved in today's Chinese (yǒng). Another example is the character for "to come" 来 , which originally meant "wheat" (today: 麦 ).

Kokkun

The following character categories are specific to Japan.

A number of characters have changed their meanings when they were adopted or over the centuries. This is known as kokkun ( 国 訓 ). Examples are:

- 沖 jap. chū , oki : high seas; chinese chōng : rinse

- 椿 jap. chin , chun , tsubaki : camellia ; chin. chūn : Chinese sura tree

- 茸 jap. jō , nyu , kinoko , take : mushroom , sponge ; chin. róng : shoot , shoot, germ, bast of an antler; Antler bud; fluffy, juicy and tender

The opposite is also the case: in Japan characters are still used in their original meaning, while in China a new meaning has long dominated.

Kokuji

In addition to the differences in form, usage, pronunciation and meaning, there are also kanji that are unknown in China because they are Japanese inventions. These Kokuji ( 国 字 'national characters' ) or Wasei Kanji ( 和 製 漢字 'Kanji created in Japan' ), a total of several hundred, were created in Japan according to the logic of Chinese characters. As already mentioned, most of the signs are names for fish species.

- 峠 tōge (mountain pass)

- 榊 sakaki ( bulky shrub )

- 畑 hatake (dry field)

- 辻 tsuji (intersection)

- 働 DŌ , hatara (ku) (to work)

- 躾 shitsuke (discipline)

- 粁 kiromētoru (kilometers)

- 瓱 miriguramu (milligrams)

Systematics of the radicals

The oldest Chinese lexicon for Chinese characters is the Shuowen Jiezi from the year 121 AD. The characters there are classified according to a system of elementary characters, the so-called radicals . The Shuowen Jiezi knew 512 radicals, but this number has been reduced further, so that the most widespread list of traditional radicals today uses 214 class symbols. This classification was mainly supported by the Kangxi Zidian from 1716, which already contains about 49,000 characters. Simplified character dictionaries use different numbers of radicals, often 227 radicals . Japanese dictionaries also use different numbers of radicals; most works are based on the 214 traditional ones.

If a character is used as a radical, it often changes its shape. The character 火 - "fire" - for example, when it is on the left as in 焼 - "baked" - is easily recognizable when it occupies the lower half as in 災 - "catastrophe" - but in many characters only are four dashes ( 灬 ) left as in 然 - "natural".

In many signs the radical is identical to the signified (see under phonograms ), so that often no distinction is made between the two terms. However, this leads to confusion, since not every signified is also a radical and therefore some signs are sorted under a radical other than the significant.

Readings

While the characters in Chinese can only be read in one or two ways in most cases (there are often three, four or more readings in classical written language, but these are hardly used in modern standard Chinese), it is somewhat more complicated in Japanese. There are basically two categories of readings: the Sino-Japanese reading ( 音 読 み on'yomi ), which was adopted from Chinese, and the Japanese reading ( 訓 読 み kun'yomi ), in which ancient Japanese words were assigned to Chinese characters.

Most of the characters have exactly one Sino-Japanese reading, but sometimes different readings from different eras and / or Chinese dialects have been adopted, so that some characters also have two, very rarely three. The Kokuji developed in Japan usually have no on-reading at all.

It is even more confusing with the Japanese readings. Rarely used characters usually have no Kun-reading, while frequently used characters can have three, four or even more.

One of the frontrunners is the character 生 with the meaning "life, birth", which in NTC's dictionary has two On readings, 17 Kun readings and another 4 special readings ( Jukujikun ).

In Japanese Kanji lexicons and Japanese textbooks, the On reading is usually given in Katakana and the Kun reading in Hiragana . This is primarily for the sake of clarity.

example

The character 大 with the meaning “large” has the Kun reading ō and two On readings, tai and dai .

| word | Romaji | reading | meaning | comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 大 き い | ō kii | Kun | big | appended hiragana characters ( き い ) indicate kun reading |

| 大 げ さ | ō gesa | Kun | exaggerated | |

| 大 口 | ō kuchi | Kun | Boasting | Kanji compound - character composition - with Kun-readings |

| 大陸 | tai riku | On | continent | |

| 大 気 | tai ki | On | the atmosphere | |

| 大使 | tai shi | On | ambassador | |

| 大学 | dai gaku | On | University, college | |

| 大好 き | dai suki | On ( 大 ), Kun ( 好 ) | to like sth. very much | Mixture of on and kun readings (Jūbako-yomi) |

| 大丈夫 | dai jōbu | On | "everything OK" | |

| 大人 | o tona | Jukujikun | Adult | Special reading (independent of Kun and On readings of the individual characters) |

Sino-Japanese reading

The Sino-Japanese reading, or on reading, is the same as the Chinese reading, although it has adapted to Japanese phonetics over time. In addition, readings have been taken over to Japan in several epochs, so that today one can differentiate between several different on-readings:

- The go-on ( 呉 音 ), named after the historic Southeast Chinese Wu dynasty , 3rd century.

- The canon ( 漢 音 ), named after the Han dynasty , but its pronunciation more in line with the time of the Tang dynasty , 7th to 9th centuries, derived from the dialect of the capital Chang'an .

- The Tō-on ( 唐 音 ), named after the Tang Dynasty , but its pronunciation more in line with the Song Dynasty and Ming Dynasty , a collective term for all new readings from the Japanese Heian period to Edo Time .

- The Kan'yō-on ( 慣用 音 ), "false" readings that have become the standard.

(For the linguistic historical meaning of these expressions: see On reading .)

Since not only the readings, but also the meaning and use of individual characters have changed over the centuries, different on readings often correspond to different meanings.

| Kanji | meaning | Go-on | Canon | Tō-on | Kan'yō-on |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 明 | bright | myō | my | min | * |

| 行 | go | gyō | kō | on | * |

| 極 | extreme | goku | kyoku | * | * |

| 珠 | pearl | * | shu | * | ju , too |

| 度 | Degree | do | taku | to | * |

The most common reading is the canon. Tō-on is found in words like 椅子 isu , "chair" and 布 団 futon . The go-on occurs especially with Buddhist terms such as 極 楽 gokuraku "paradise".

The On reading is more similar to today's South Chinese dialects than the North Chinese , which served as the basis for the modern Mandarin language, for two reasons . Chinese navigators and traders who spread the language came mainly from the southern provinces . On the other hand, the southern Chinese dialects are closer to the classical Chinese pronunciation, which form the basis for the onyomi, while the northern Chinese dialects have experienced a strong sound shift in the last few centuries .

The On reading is typically a monosyllabic reading as each character corresponds to a Chinese syllable. In Japanese, a syllable consists of a consonant followed by a vowel or just a vowel. The classical Chinese of the 6th to the 10th century ( Middle Chinese but) knew several final sounds of syllables: beside the still preserved Nasal also a number of plosives , which have been lost in modern Chinese. In the On reading of numerous Kanji, however, they have been preserved as one of the syllables ku , ki , tsu or chi . The nasal sound has either been preserved as n or has become an elongated vowel, usually ei or ou .

The palatalization of the consonants in syllables such as gya , nyu or cho only developed through the grinding of Sino-Japanese words; it does not occur in "pure Japanese" words.

The onyomi is mainly used for compound words made up of at least two characters, in most cases nouns, suru verbs and na adjectives . Stand-alone Kanji are usually pronounced in the Kun reading, but there are a few exceptions, especially if there is no Kun reading.

One problem with on-reading is the large number of homophones . For example, there are over 80 characters that can all be read shō . With combinations of common syllables like sōshō, there are usually half a dozen words that are read like this, in the case of sōshō these include sind "master", 相称 "symmetry", 創傷 "wound" and 総 称 "general".

A special form of on-reading are the so-called Ateji , characters that are used purely phonetically to write a certain word. Mostly they are old non-Chinese foreign words that were adopted into Japanese before the 19th century. One example is the tempura kanji spelling ( 天 麩 羅 ) , which is rarely used today .

Similar to the Latin and Greek loan words in German, the Sino-Japanese compound words are mainly used for technical terms and "sophisticated vocabulary". Some compound words go back to existing Chinese words, others are Japanese creations. In fact, with a number of modern compounds such as “ philosophy ” ( 哲学 tetsugaku ) it is disputed whether they were first created in China and then adopted in Japan, or vice versa.

Characters created in Japan usually have no on reading, for example the character 込 , which is only used for the verb 込 む komu "; come in ”is used. In other cases, similar to the Chinese phonetic ideograms, an on reading has been transferred to the new character, as in the case of the characters 働 “work” with Kun'yomi hataraku and On'yomi dō , and 腺 “gland”, which is not just the transferred meaning from the character 泉 sen , "source", but also the reading.

Japanese reading

The Japanese or Kun reading is used with Japanese words that have been assigned to Chinese characters by meaning. One example is the character 東 "East", whose on reading, taken from Chinese, is tō . Two words with the meaning east already existed in old Japanese, higashi and azuma , these now became the kun reading of the sign. Some characters like 版 han "printing plate" are always read in Sino-Japanese and do not have a Kun reading. Others like the 生 already mentioned have over 20, including verbs like 生 き る ikiru , “to live” and 生 む umu “to have children” and adjectives like nama “raw, unprocessed”.

Most of the verbs are Kun'yomi readings, where the Kanji stands for the root of the word and the conjugation ending is formed by appending Hiragana ( Okurigana ). Often, however, there are several verbs that are written with one character, in this case more syllables are written out in hiragana in order to distinguish the verbs. In the case of 生 , the verbs 生 き る ikiru , “to live” and 生 け る ikeru , “to keep alive” could not be distinguished if only the character itself had the ending -ru ( 生 る ).

According to Japanese phonetics , the Kun'yomi consists of syllables consisting of a consonant + vowel or just a vowel. Most of these readings are two or three syllables long.

Guidelines for the assignment between characters and Kun-reading were only established with the writing reform of 1900. Until then, it was possible to decide according to personal preferences which character was used to write which word. Even in modern Japanese, there are several characters to choose from for many words. In many cases the meanings are the same or only differ in nuances. The verb arawareru can be written as 現 れ る and as 表 れ る . In both cases it means "to emerge, to emerge". The former is more likely to be used when the verb relates to people, things or events, the latter for feelings. Sometimes the differences are so subtle that dictionaries don't even list them.

The difference is clearer with other words. For example, naosu means “to heal” in the spelling す , while 直 す means “to repair”.

The Kun reading is usually used when a character stands alone, the so-called seikun ( 正 訓 ). There are also the so-called Jukujikun readings, in which two or more characters together form a word and are only read in a certain way in this combination.

Nanori

Some kanji have readings that appear only in person or place names, called nanori . These readings can have different origins. Place names often contain old words or readings that are no longer used in modern language. An example is the reading nii for the character 新 “new” in the names Niigata ( 新潟 ) and Niijima ( 新 島 ). In Okinawa many place names come from the Ryūkyū languages , in northern Japan from the Ainu language .

Some of the more well-known place names read the characters in Sino-Japanese, including Tōkyō ( 東京 ), Kyōto ( 京都 ), Beppu ( 別 府 ), Mount Fuji ( 富士山 ) and Japan itself ( 日本 Nihon). Such place names are mostly more recent, cities and towns traditionally have purely Japanese names, such as Ōsaka ( 大阪 ), Aomori ( 青森 ) and Hakone ( 箱根 ).

Family names like Yamada ( 山田 ), Tanaka ( 田中 ) and Suzuki ( 鈴木 ) are also in the Kun reading, with a few exceptions in On reading such as Satō ( 佐藤 ). For first names, the readings are mixed, some are purely Japanese, some in on-reading, some read differently from everything. Some Japanese first names are only written in katakana or hiragana. Kanji, which are often used with names, often have five or six different readings that are also used exclusively with names. Popular first names, especially among boys, can have up to two dozen different spellings. For this reason, Japanese people always have to write and read their names on Japanese forms .

- see: Japanese name

Gikun

Gikun ( 義 訓 ) are readings that do not correspond to the standard On or Kun reading. Most gikun are jukujikun ( 熟字 訓 ), kun readings in which a Japanese word is written with two characters, because the Chinese word with the same meaning is also a combination of characters. Gikun also appear in proverbs and idioms. Some gikun are also family names.

Ateji

Another category are Kanji, which are used phonetically to write certain foreign words, the so-called Ateji . In modern Japanese, this function is performed by the katakana .

Use of the readings

The general rule is that a character is read in Kun-Reading when it is on its own. If it is in a compound word ( 熟語 jukugo ), i.e. as a term in several Kanji, it is read in on-reading. According to this rule, the two characters for east ( 東 ) and north ( 北 ) are read in Japanese as higashi or kita if they form a separate word . In the compound northeast ( 東北 ), however, the reading is Sino-Japanese as tōhoku .

This rule applies with some certainty to many words, for example 情報 jōhō “information”, 学校 gakkō “school”, and 新 幹線 Shinkansen .

Some characters were never given a Japanese reading, instead they are also read in the onyomi when they stand alone: 愛 ai “love”, 禅 zen , 点 th “point”. It becomes difficult with characters such as 間 “space”, which can be read alone, kan or ken (on reading), aida , ma or ai (kun reading). The meaning is more or less the same in all 5 cases, there are only idiomatic expressions in which a reading is usual in each case.

Kanji to which grammatical endings (Okurigana) written in Hiragana “stick” are read in kunyomi . This mainly applies to conjugable words (see Japanese grammar ), i.e. verbs like 見 る miru "see" and adjectives like 新 し い atarashii "new". Okurigana are sometimes attached to nouns, as in 情 け nasake "sympathy", but not always, for example in 月 tsuki "moon".

It takes a bit of practice to distinguish okurigana from particles and other words written in hiragana. In most cases this is clear because the most common particles ( で , に , を , は ) rarely or never appear as okurigana. In some cases, however, it only helps to know the word, so 確 か tashika is “certainly” marked by an か ka , which also occurs as a particle, e.g. B. in 何 か nanika “something” and as a question particle.

Here we come to the first exception: not every compound is read in Sino-Japanese. There are a number of terms read in Japanese, especially from culture, from the field of Japanese cuisine and from Shinto . Okurigana are also appended to indicate that these compounds should be read in Japanese. Examples are 唐 揚 げ - also 空 揚 げ - Karaage (a dish) and 折 り 紙 Origami . However, the okurigana are not mandatory, frequently used terms assume that the reader knows what they are about and the characters are saved. You can therefore find 揚 karaage ( 空 揚 ) and 折紙 origami in texts for the two examples . Further examples are 手紙 tegami "letter", 日 傘 higasa "parasol" and 神 風 kamikaze .

Since there are still obscuracies in languages for every rule and exception in actual use, there are also some rare compounds in which Japanese and Sino-Japanese readings are mixed. This is called either Jūbako-yomi (On-Kun) or Yutō-yomi (Kun-On). Both terms are named after words in which this special case occurs. One is 重 箱 jūbako , the name for a multi-part wooden box in which food was served, and 湯 桶 yutō "water bucket".

As with single characters, it also applies to compound words that there are sometimes several readings for the same characters. When the readings have the same meaning, it is often just a matter of personal preference . Sometimes historical readings still appear in idioms. With other words, different readings also have different meanings, here it is important to deduce the correct homograph from the context. An example is 上手 , a combination of 上 "above" and 手 "hand". Usually it is read jōzu and means "skillfully, to do something well". However, it can also be read uwate or kamite and then means “upper part”. In addition, with the addition of い ( 上手 い ), it is a less common spelling of the word umai "clever" (usually 旨 い ).

Pronunciation aids

Because of the great inconsistency, irregular and unusual readings are marked with small hiragana (more rarely katakana) above or next to the characters. These are called furigana . Alternatively, so-called kumimoji are also used, which are instead in the text line / column behind or below the characters.

You can find among others:

- in children's books and school books

- with names of places, people, temples, deities, rivers, mountains ...

- in language gimmicks by the author, especially in manga

- Loan words that are written in Kanji but whose pronunciation does not correspond to the On or Kun reading (often on menus in Chinese restaurants in Japan)

- rare or historical kanji

- Technical terms, especially from Buddhism

Advantages and disadvantages

Japanese texts for adults can be “cross-read” at high speed if necessary. Since the main content is written with Kanji and complex terms can be represented with only a few Kanji, one can quickly grasp the meaning of a text by jumping from Kanji to Kanji, ignoring the other character systems. On the other hand, one can see from the total proportion and the level of difficulty of the Kanji of a text for which age or educational group it was preferably written.

The major disadvantage of Kanji is the high learning curve, both for Japanese and for foreigners who are learning the language. Japanese children have to learn their first characters (the hiragana syllabary ) in kindergarten , and on average they only master the full range of characters used in normal correspondence in high school. Learning additional characters is a prerequisite for understanding specialist texts.

Simplifications and reforms

On November 16, 1946, the Japanese Ministry of Education published a list of 1850 characters, the Tōyō Kanji , which have since formed the basis of the Japanese writing system together with the Kana. A fixed curriculum was drawn up for the characters for each school year.

In this list, a number of characters have been simplified in their writing in order to make it easier to learn to write. The standard was fixed in the "Tōyō Kanji characters form list" ( 当 用 漢字 字体 表 Tōyō Kanji Jitai Hyō ). From that moment on, the old written form was referred to as “old characters” ( 旧 字体 or 舊 字體 Kyūjitai ). In most cases the kyūjitai correspond to the traditional Chinese characters . The new forms were accordingly referred to as Shinjitai ( 新 字体 ). Variants that differ from the Shinjitai should no longer be used. However, these are only guidelines so that many characters can still be used according to personal preference.

Examples

- 國 → 国 kuni (country / province)

- 號 → 号 gō (number)

- 變 → 変 hen , ka (waru) (change)

Many of these simplifications were already in use as handwritten abbreviations ( 略 字 Ryakuji ), which, unlike the full forms ( 正字 seiji ), were only used in an informal context. Some characters have been simplified in the same way in Japan and the People's Republic of China, but most have not, with Chinese simplification often being more profound than Japanese. Although both reforms were carried out at about the same time, there was no agreement given the political situation at the time.

The simplified forms (Shinjitai) are only used for characters that are on the list of Jōyō Kanji , while rare characters (Hyōgaiji) are still in the traditional form, even if they contain elements that have been simplified in other characters. Only the newspaper Asahi Shimbun carried out the reform consistently, which also applied the simplification to these other symbols. The simplified character forms beyond the Jōyō Kanji are therefore called Asahi characters .

Total number of kanji

The actual number of kanji is a matter of design. The Daikanwa Jiten is nearly full with around 50,000 characters. However, there are historical as well as more recent Chinese dictionaries that contain over 80,000 characters. Rare historical variants of many characters are listed and counted individually. Character dictionaries sufficient for everyday use contain between 4,400 (NTC's New Japanese-English Character Dictionary) and 13,000 (Super Daijirin) characters.

The list of jōyō kanji taught in the school is 2,136 characters. In academic subjects such as law, medicine or Buddhist theology, knowledge of up to 1,000 other Kanji is necessary in order to understand the technical terms. Well-educated Japanese are often (at least passively) proficient in over 5,000 Kanji, which is particularly important for reading literary texts.

Kyōiku kanji

The Kyōiku Kanji ( 教育 漢字 , "teaching Kanji") comprise the 1,006 characters that Japanese children learn in elementary school. Up until 1981 the number was 881. There is a list in which the Kanji to be learned are listed for each school year, called gakunen-betsu kanji haitōhyō ( 学年 別 漢字 配 当 表 ), or gakushū kanji for short .

Jōyō kanji

The Jōyō Kanji ( 常用 漢字 , "Everyday Use Kanji") contain, in addition to the Kyōiku Kanji, all characters that are taught in middle and high school, a total of 2,136 Kanji. In texts that do not apply to a professional audience, most characters that do not belong to the jōyō kanji are with furigana provided -Lesungen. The Jōyō Kanji List was introduced in 1981. It replaced the Tōyō kanji (comprising 1,850 characters) from 1946 and originally consisted of 1,945 characters until 196 new kanji were added and five removed when the list was updated in 2010.

Jinmeiyō Kanji

The Jinmeiyō Kanji ( 人名 用 漢字 , "Name Kanji") are a list of currently 863 characters that may be used in addition to the Jōyō Kanji in Japanese names (first names, family names, geographical names). This list has been extended several times since 1946.

Kanji Kentei

The Japanese government conducts the so-called Kanji Kentei test ( 日本 漢字 能力 検 定 試 験 Nihon kanji nōryoku kentei shiken ) three times a year, which is intended to test the ability to read and write Kanji. It comprises a total of twelve levels; At the highest level, which is particularly prestigious for successful graduates (level 1), knowledge of approx. 6,000 Kanji is required. At the Kanji Kentei in March 2015, which a total of 741,377 participants took, 85 participants passed the level 1 test.

See also

- Hanja (Sinocorean)

- Hán Tự (Sinovietnamese)

- Han unification

literature

- John DeFrancis : The Chinese Language. Fact and Fantasy . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1990, ISBN 0-8248-1068-6 .

- William C. Hannas : Asia's Orthographic Dilemma . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1997, ISBN 0-8248-1892-X (Paperback).

- James W. Heisig , Robert Rauther : Learn the Kanji and keep volumes 1 to 3. New series . Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-465-04191-7 .

- Stephen Kaiser : Introduction to the Japanese Writing System . In: Kodansha's Compact Kanji Guide . Kondansha International, Tokyo 1991, ISBN 4-7700-1553-4 .

- Joyce Yumi Mitamura , Yasuko Kosaka Mitamura : Let's Learn Kanji . Kodansha International, Tokyo 1997, ISBN 4-7700-2068-6 .

- Jürgen Stalph : Basics of a grammar of the Sino-Japanese writing (= publications of the East Asia Institute of the Ruhr University Bochum ). Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 3-447-02944-7 .

- J. Marshall Unger : Literacy and Script Reform in Occupation Japan. Reading Between the Lines . 1996, ISBN 0-19-510166-9 .

Web links

- Change in Script Usage in Japanese: A Longitudinal Study of Japanese Government White Papers on Labor , discussion paper by Takako Tomoda in the Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies , August 19, 2005 .

Dictionaries

- Japanese-German dictionary of characters 7150 characters - by Hans-Jörg Bibiko (German, Japanese)

- Japanese Kanji Dictionary on jisho.org (English, Japanese)

- Japanese Kanji Dictionary on tangorin.com (English, Japanese)

- Japanese Kanji Dictionary on www.romajidesu.com (English, Japanese)

- Japanese Kanji Dictionary on www.yamasa.org (German, English, Japanese)

Trainer

- www.kanji-trainer.org Free Kanji learning program based on the index card principle with explanations of the components and mnemonics for all characters

- Free writing practice for JLPT, Kankentest, Kyōiku, Jōyō Kanji and more

- Practice Kanji , Java applet for learning and practicing the Kanji

Individual evidence

- ^ Elementary Japanese for College Students . Compiled by Serge Eliséeff, Edwin O. Reischauer and Takehiko Yoshihashi. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge 1959, Part II, p. 3

- ↑ There notes on pronunciation

- ↑ Volker Grassmuck: The Japanese writing and its digitization . In: Winfried Nöth, Karin Wenz (Ed.): Intervalle 2. Media theory and digital media . Kassel University Press, Kassel 1999., ISBN 3-933146-05-4 (chapter also online) ; Subsection "The Signs of the Han "

- ^ WG Aston: Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan From the Earliest Times to A, Part 697, Routledge, 2010, p. 87 [1]

- ↑ a b Felix Lill: Not the forest for all the signs. Even native speakers surrender to the abundance of Kanji - a Chinese-Japanese character writing . In: Die Zeit from May 7, 2015, p. 38.

- ↑ Richard Sears: Characters 馬 after Japanese pronunciation - バ BA ・ う ま uma ・ う ま ~ uma ・ ま ma - after Pinyin mǎ - horse. In: hanziyuan.net. Retrieved June 20, 2020 (Chinese, English).

- ↑ Chinese characters 馬 according to Japanese pronunciation - バ BA ・ う ま uma ・ う ま ~ uma ・ ま ma - according to Pinyin mǎ - horse. In: tangorin.com. Retrieved June 20, 2020 (Japanese, English).

- ↑ Chinese characters 馬 according to Japanese pronunciation - バ BA ・ う ま uma ・ う ま ~ uma ・ ま ma - according to Pinyin mǎ - horse. In: Wadoku . Retrieved June 20, 2020 (German, Japanese).

-

↑ Commons : Ancient Chinese characters project - album with pictures, videos and audio files

- ↑ Hary Gunarto : Building Dictionary as Basic Tool for Machine Translation in Natural Language Processing Applications , Journal of Ritsumeikan Studies in Language and Culture, April 2004 15/3, pp 177-185 Kanji