Shinkansen

Shinkansen ( Japanese 新 幹線 , [ ɕĩŋkaãsẽɴ ], dt. "New main line") is both the name of the route network of Japanese high-speed trains of the various JR companies and of the trains themselves.

In the original sense, Shinkansen is the name of the regular - gauge high-speed rail network introduced in 1964 and not the trains themselves. It is formed from the characters shin ( 新 ) for "new", kan ( 幹 ) for "trunk / main", sen ( 線 ) for "route, line" and thus designates the backbone function for the rest of the railway network, via which the major Japanese cities are connected with a maximum speed of up to 320 km / h.

overview

The Shinkansen is less characterized by the absolute maximum speed of the railcars (443 km / h in the test run) than by its consistently high cruising speed on a high- speed network that is structurally completely separate from local and freight traffic . The “Nozomi Superexpress” between Tokyo and Nagoya, including stops at the train station, has an average speed of 206 km / h.

The Shinkansen is considered an extremely safe means of transport, the Japanese high-speed trains are the safest in the world. Since the first line went into operation in 1964 until today, there has been no accident with fatal consequences. Even in a 6.4 magnitude earthquake on October 23, 2004, when a train derailed for the first time, there was no personal injury.

The punctuality is at a high level internationally, but it is difficult to compare it with the values and systems in other countries. The individual JR companies record delays separately from one another, sometimes with different methods, which means that there are no standardized statistics for the Shinkansen network. Unlike z. In Japan, for example, in Germany, France or Switzerland, delays due to force majeure (such as heavy rain, snow, typhoon) are generally not counted. The separation of the high-speed network from local and freight traffic, the almost continuous fencing of the routes, robust technology and good maintenance have a positive effect on punctuality.

Historically, because of the mountainous landscape in the long-distance railway network, the cape gauge of 1067 mm prevailed in Japan because it allows the alignment to be better adapted to the terrain. Since it was not possible to significantly increase the speed on the old routes, the wider standard gauge of 1435 mm was chosen for the Shinkansen network and a route with as few bends as possible was achieved using many engineering structures. The existing, partially parallel routes were retained for local and freight traffic.

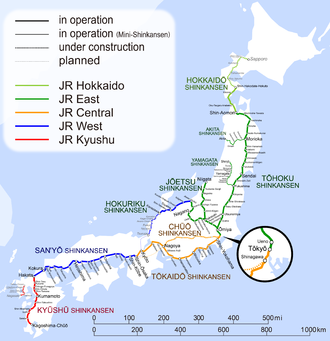

The Shinkansen route network will have a total length of 2765 km in 2020. The first line with a length of 515.4 km was opened on October 1, 1964 between the capital Tokyo and Osaka , making it the world's oldest expressly designed high-speed railway. The comparable French high-speed line Paris – Lyon followed in 1981 . The latest expansion (March 26, 2016) is the section between Shin-Aomori and Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto on Hokkaido . Four more routes with a total length of 733 km with planned commissioning between 2022 and 2031 are under construction and two more routes are being planned.

The total economic benefit of the Shinkansen system was estimated in 1994 at 3.7 billion euros per year.

history

Since the beginning of the railway construction in the time of the Meiji Restoration , railway lines have been built almost exclusively with a gauge of 1067 mm (Cape gauge). Even newer lines were built in this gauge to enable a smooth connection to the rest of the network. In the age of steam traction in particular , this meant a lower maximum speed due to the smaller dimensions of the locomotives . Up until the 1950s, a maximum speed of 100 km / h could not be exceeded, while in Germany as early as the 1930s, express trains ran at up to 160 km / h. There have been repeated efforts to re- track the routes to the standard lane , but due to the high costs and the great difficulties of the conversion during ongoing operations, these were not implemented.

Japanese technicians had their first experiences with “high-speed traffic” on the regular-gauge Minamimanshū railway in Manchuria (now northeastern China). From 1934 onwards, the Ajia express train, pulled by a streamlined steam locomotive, covered the 701 km long route between Dairen ( Dalian ) and Shinkyō ( Changchun ) in eight and a half hours at a top speed of 120 km / h , at an average speed of 82 km / h. While the top speed was not spectacular in an international comparison and even by Japanese standards, the fully air-conditioned cars were groundbreaking.

In the second half of the 1930s, traffic on the Tōkaidō and San'yō lines increased so much that from 1939 the then Japanese Ministry of Railways planned to build a new, separate, standard-gauge line for high-speed trains and from September 1940 with the Construction has started. The speed of these trains should far exceed that of the Ajia express train, so that a travel time of four and a half hours between Tokyo and Osaka and nine hours between Tokyo and Shimonoseki could be achieved. However, as a result of the war, construction work was gradually stopped. The fact that the land acquisition was largely completed before the end of the war proved beneficial for the later construction of the Shinkansen route.

While the drive concept of trains hauled by steam or electric locomotives was still favored at the time of the multi-storey train project, it was realized in the 1950s that multiple units are much cheaper, especially for the Japanese route conditions with many inclines and curves , as these are higher Enable acceleration and less load on the superstructure due to the more favorable load distribution. Both the Odakyū class 3000 SE introduced in 1957 and the class 20 railcars (later BR 151 - JNR-Kodama railcars ) put into service in 1958 for the Kodama express connection (Tokyo – Osaka) demonstrated the advantages of this technology in impressive fashion. The latter set the speed record for narrow-gauge trains in 1959 at 163 km / h. These positive experiences led to the fact that multiple units were also used in the Shinkansen project.

By the end of the 1950s, the Japanese economy had recovered to such an extent that the Tōkaidō line again reached its capacity limits despite being fully electrified. At times when you rather propagated the air and road transport, it was still a brave decision to build a high-speed railway between Tokyo and Osaka, probably not least the "fathers of the Shinkansens" Shima Hideo and Sogo Shinji is due . The project was approved in 1958, and construction work began on April 20, 1959, with buildings already being used for the multi-storey project. On May 1, 1961, the independent Japanese State Railroad, JNR, received a loan of $ 80 million under the strict condition of opening the line by 1964.

After the first test drives on a section (between today's Shin- Yokohama and Odawara stations) had taken place in 1962, it was possible to punctuate the Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo on October 1, 1964 on the 515.4 km long route between Tokyo and Shin- Osaka ( Tōkaidō -Shinkansen ) traffic can be added. With the twelve-car class 0 multiple units running every half hour , the transport capacity of the express and express trains that had existed up to that point was significantly exceeded. Although the trains were at a maximum speed of 210 km / h on a travel designed three hours and ten minutes, but there was at that time had no experience with a regular operation at such high speeds, it held initially the travel time of the Super Express train Hikari on four hours (compared to the previous six and a half hours still a significant reduction) and reduced the top speed to 200 km / h. In the following year, the top speed could be increased to 210 km / h.

In 1967 the Tōkaidō Shinkansen carried its hundred millionth passenger and in 1976 its billionth. About four billion passengers used the trains from 1964 to 2005. Today, the Nozomi super express train of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen covers the 515.4 km Tokyo – Shin-Osaka route in up to 2 hours and 30 minutes with just four stops, which is an average travel speed of 206 km per hour. The trains now handle around 30% of long-distance traffic in Japan.

From commissioning to privatization of the Japanese state railway

On October 10, 1964, with the beginning of the Summer Olympics in Tokyo, regular operations began with the Series 0 , specially developed for the Shinkansen , which was used here for the first time. The top speed was initially 200 km / h, but was increased to 210 km / h when the timetable changed on October 1, 1965, after the load-bearing capacity of the track was ensured.

The journey between the two economic centers of Japan, Tokyo and Osaka, had to be done by express train on the old route since 1958, returning on the same day, even if the stop was limited to 2 hours due to the schedule. With the new Shinkansen connection, travel time took a back seat, which triggered significant changes in passenger behavior. There was an increased demand in business and private travel, so that as early as 1970 for the opening of the world exhibition in Osaka, the previously used 12-car trains were expanded to 16 cars.

Due to the rapid increase in traffic, the Japanese state railways had to invest considerable funds in the Shinkansen system in the years after 1964 as well as in the increasing shuttle traffic in urban areas. This was one of the reasons why the state railway slipped into deficit after 1964, which continued to widen in the following period. The Shinkansen initially became an economic problem, but later became a main source of income for the state railways.

In the following years, after drastic improvements in transport capacity, the demand on the San'yō main line (from Osaka to western Japan) grew, so that in 1967 the construction of the extension of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen began. On March 15, 1972 the line to Okayama , on March 10, 1975 the line to Hakata (in Fukuoka ) was opened.

Then the northward expansion began. In 1971 the construction of the Tōhoku Shinkansen (northeast Japan towards Sendai ) and the Jōetsu Shinkansen (to Niigata ) began. In 1974, construction began on the Narita Shinkansen to Narita International Airport .

However, difficulties in buying up land and water ingress in tunnels on both of the aforementioned routes delayed construction work by five years. The Narita Shinkansen project was even completely discontinued. Finally, environmental problems in the vicinity of the railway line worsened due to noise pollution and vibrations. As a result of the financial distress of the state railway, the fares were repeatedly increased. Because of this and the frequency of labor disputes and strikes, the number of passengers showed a downward trend. The labor law disputes also prevented technical improvements in rail operations, so that one can speak of a temporary stagnation of the Shinkansen expansion in the late 1970s.

1982 was the temporary terminus Ōmiya (since 2001 city Saitama the Tohoku Shinkansen opened), in 1985, the delayed through purchase of real estate following the Central Station Ueno . When building the Tōhoku and Jōetsu line, the land costs increased significantly. Due to the increasing burden of construction costs, the finances of the state railway recently reached catastrophic conditions, so that in 1987, under the cabinet of Yasuhiro Nakasone, the splitting and privatization of the state railway was vigorously advanced.

The four lines that existed at the end of the 1980s (total length: 1831 km) ran over 200 million passengers a year. The market share between Tokyo and Osaka (around 500 km) was 85%, between Tokyo and Hiroshima (around 800 km) 65% and between Tokyo and Hakata (1100 km) around 30%. The train sequence in rush hour was up to four minutes.

From the spring of 1985, a set of prototypes of new double-deck coaches was tested that were 1.5 m higher than the single- deck coaches.

From the founding of Japan Rail (JR) to the present

With the division and privatization of the state railway, the Tōhoku and Jōetsu Shinkansen are carried through by JR East ( JR 東 日本 , JR Higashi Nihon), the Tōkaidō Shinkansen by JR Central ( JR 東海 , JR Tōkai) and the San'yō Shinkansen JR West ( JR 西 日本 , JR Nishi Nihon) operated. Initially, the individual railway companies maintained separate operating companies that paid for the costs of maintaining and operating the routes in their region, but rented the route itself from a central Shinkansen operating organization ( 新 幹線 保有 機構 , Shinkansen Hoyūkikō ). The latter received rental income without having to carry the route maintenance itself. Its purpose primarily served the financial equalization between the JR railway companies.

However, this system became flawed as the railroad companies stabilized and a stock exchange listing came into focus. The fee system did not adequately reflect the financial strength of the railway company and caused difficulties for the JR companies in accounting for assets and liabilities. As a result, the system was redesigned in 1991. Each railway company buys its Shinkansen routes in 60 annual installments from a railway operating foundation ( 鉄 道 整 備 基金 , Tetsudō Seibikikin ), which arose from the Shinkansen operating organization.

After the division and privatization of the state railway, positive developments in the equipment and design of the rolling stock quickly became apparent after the technology and operation of the Shinkansen had previously stagnated.

As an example of the aforementioned development, JR East has decided not to build new, fully upgraded lines in standard gauge and instead used special rolling stock on old lines (1067 mm). This so-called mini-Shinkansen can also be operated continuously on the old lines (on tracks with two-lane expansion).

In 1992 the 400 series was put into operation on the Yamagata line between Fukushima and Yamagata, in 1997 the E3 series on the Akita line between Morioka and Akita and in 1999 the E3-1000 series on the extension of the Yamagata line between Yamagata and Shinjō .

The top speed, which was limited to 210 km / h for a long time, was gradually increased to over 300 km / h in the final phase of the state railway. The new building projects that had been frozen in the meantime were resumed. On the Tōhoku Shinkansen ( Hachinohe - Aomori ) from 2002, on the Hokuriku Shinkansen ( Nagano - Kanazawa ) from 1997. The Shinkansen network comprises - as of 2003 - a total length of 2175 km. At that time, 215 km were under construction and 349 km in the planning. The Kyūshū Shinkansen Hakata - Kagoshima was expanded from 2004. Construction work also progressed on the Hokkaidō Shinkansen .

After all, the number of professional and student commuters has increased in recent years. Due to the rise in land prices in the metropolitan areas as part of the bubble economy , more people from the prefectures with Shinkansen access (especially to Tokyo from the Tochigi , Gunma and Shizuoka prefectures ) used this alternative. In February 1983 season tickets for the Shinkansen were introduced, which are especially issued by companies to their employees (in Japan it is common for companies to reimburse their employees for travel expenses to work), especially since the tax allowances for travel expenses were increased at the same time. The commuters in the morning and in the evening increased the utilization of the trains, so that timetables specially tailored to commuters were introduced. In response, JR East has significantly increased the passenger capacity per wagon with the double-decker "Max" series of wagons.

Effect of the Shinkansen beyond Japan

The success of the Shinkansen had an impact on many European countries, where plans were made to modernize the rail network, which is much older than Japan's Shinkansen. In 1967 the French experimental train TGS reached a speed of more than 200 km / h, which was soon exceeded by other European high-speed trains. In 1981, the first TGV line was opened with a maximum operating speed of 270 km / h, which made the trains among the fastest in the world at the time, even before the Shinkansen.

Later, high-speed lines and high-speed trains were also planned in Germany and Italy, which were also implemented with the ICE and Pendolino . Other countries have also studied the introduction of its own high-speed trains, but led for the time being, such as Spain , the French and German technology one.

In countries with an already widespread standard gauge network (note: the classic Japanese long-distance railway network is Cape Gauge), existing sidings to train stations are often used. Depending on the circumstances, other feeder lines are used instead of new lines or existing lines are expanded. As a system of routes, vehicles and access points, the Shinkansen is still an exception today.

Maximum speeds in regular operation

In September 2006, the Velaro E from the German multinational Siemens set a new world speed record for series-production trains at 404 km / h. For the currently with max. 320 km / h operated French TGV, a maximum speed of 360 km / h is planned. In Germany, ICEs run at speeds of up to 300 km / h in passenger service.

The 500 series Shinkansen were operated at a maximum of 300 km / h until 2010. Thanks to tilting technology, the trains of the N700 series reach the same speed even on less favorable track conditions.

On the oldest route of the Shinkansen, the Tōkaidō line between Tokyo and Osaka , curves and tunnels were originally designed for a speed of 200 km / h, but are used faster today (up to 285 km / h). On the newer mountain routes of the San'yō Shinkansen with their limited curve radii and high gradients, speeds of up to 240 km / h are the rule. Especially on the Jōetsu Shinkansen route , heavy snowfalls are a particular problem that must be taken into account. Increasingly, the increased noise pollution when crossing residential areas is seen as an argument against a further increase in speed.

Nevertheless, from 2004 to 2009, test drives were carried out for a cruising speed of 360 km / h with the E954 and E955 models . The E5 and E6 series developed from this reach 320 km / h in regular operation on the Tōhoku Shinkansen .

stretch

Since the opening of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen from Tokyo to Shin-Osaka in 1964, the Shinkansen network has been continuously expanded. By 1973, seven lines under the Shinkansen Railway Development Act throughout the country ( 全国 新 幹線 鉄 道 整 備 法 , Zenkoku Shinkansen Tetsudō Seibihō , Nationwide Shinkansen Railway Development Act ; Law No. 71 in 1970) with a maximum speed of at least 260 km / h and a minimum curve radius of 4,000 meters planned.

Lines in operation

| Surname | Endpoints | length | opening |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Tōhoku Shinkansen | Tokyo <> Shin-Aomori | 674.9 km | Morioka <> Ōmiya: 1982 Ōmiya <> Ueno: 1985 |

| Jōetsu Shinkansen | Tokyo <> Niigata | 269.5 km | Niigata <> Ōmiya: 1982 Ōmiya <> Ueno: 1985 |

|

|

|||

| Hokuriku Shinkansen | Takasaki <> Kanazawa | 345.5 km | Takasaki <> Nagano: 1998 Nagano <> Kanazawa: 2015 |

|

|

|||

| Tōkaidō Shinkansen | Tōkyō <> Shin-Osaka | 515.4 km | 1964 |

|

|

|||

| San'yō Shinkansen | Shin-Osaka <> Hakata | 553.7 km | Shin-Osaka <> Okayama: 1972 Okayama <> Hakata: 1975 |

|

|

|||

| Kyushu Shinkansen | Hakata <> Kagoshima-Chūō | 256.8 km | Shin-Yatsushiro <> Kagoshima-Chūō: 2004 Hakata <> Shin-Yatsushiro: 2011 |

|

|

|||

| Hokkaidō Shinkansen | Shin-Aomori <> Shin-Hakodate-Hokuto | 148.9 km | March 26, 2016 |

There are also the routes operated with the Shinkansen trains and the routes built according to the Shinkansen standard. However, all of these routes have so far not been operated as Shinkansen, but as conventional routes ( 在 来 線 , Zairai Sen ).

-

Mini-Shinkansen lines (the special express trains ( 新 幹線 直行 特急 , Shinkansen Chokkō Tokkyū ) that go through to Shinkansen ): expanded existing lines of the conventional railway network in which the gauge is increased from 1,067 mm cape gauge to standard gauge and the maximum speed to 130 km / h has been. In addition to the Shinkansen trains, the routes are also used by regional and local trains.

- Yamagata-Shinkansen (JR East): Fukushima <> Shinjō, 148.6 km, (Fukushima <> Yamagata: 1992, Yamagata <> Shinjō: 1999)

- Akita-Shinkansen (JR East): Morioka <> Akita, 127.3 km (1997)

- The conventional routes built according to the Shinkansen standard ( 新 幹線 規格 在 来 線 , Shinkansen Kikaku Zairaisen ): routes that were originally built as a Shinkansen depot, but were later also released for passenger traffic due to growing demand. The maximum speed is limited to 120 km / h.

- Gāla-Yuzawa Line (JR East): Echigo-Yuzawa <> Gāla-Yuzawa, 1.8 km (1990)

- Hakata-Minami Line (JR West): Hakata <> Hakata-Minami, 8.5 km (1990)

- The new routes built according to the Shinkansen route standard ( 新 幹線 鉄 道 規格 新 線 , Shinkansen Tetsudō Kikaku Shinsen ). Cape lane routes, which, however, can be driven at a top speed of over 200 km / h.

- Kaikyō Line (JR Hokkaidō): Nakaoguni depot <> Kikonai, 87.8 km (1988). Passenger and freight trains are currently only running at a maximum of 140 km / h. For the opening of the Hokkaidō Shinkansen, this line will be retrofitted with a three-rail track by 2015 so that the standard-gauge Shinkansen trains can use the route.

Lines under construction

- Hokuriku Shinkansen (JR West): Kanazawa <> Tsuruga (opening 2022)

- Kyūshū-Shinkansen (section Nagasaki) (JR Kyūshū): Takeo-Onsen <> Nagasaki, 66.7 km (opening 2023)

- Chūō-Shinkansen ( 中央 新 幹線 ) (JR Central): Tokyo (Shinagawa) < Sagamihara - Kōfu - Iida > Nagoya, 286 km (opening planned for 2027). With a top speed of 505 km / h, the travel time between Tokyo and Nagoya is to be reduced to 40 minutes.

- Hokkaidō Shinkansen (JR Hokkaidō): Shin-Hakodate <> Sapporo, 211.3 km. The line is to be completed by 2030 and then operated at a top speed of up to 360 km / h. This would reduce the travel time between Tokyo and Sapporo (1035.1 km) to 3 hours 57 minutes.

Routes in planning

- Hokuriku Shinkansen (JR West): Tsuruga <Kyōtō> Ōsaka (opening planned for 2030)

- Chūō-Shinkansen ( 中央 新 幹線 ) (JR Central): Nagoya < Nara > Osaka, 152 km (opening planned for 2037).

Long-term planned route network expansions

In addition, twelve routes were added to the basic plan in November 1973, which are to be implemented in the long term. There are no concrete plans for any of these routes. Given Japan's budgetary position, many of the routes are being scrutinized and actual implementation is not certain.

- Hokkaidō Shinkansen ( 北海道 新 幹線 ): Sapporo <> Asahikawa , 130 km

- Hokkaidō South Line Shinkansen ( 北海道 南 回 り 新 幹線, Hokkaidō Minami-Mawari Shinkansen ): Oshamanbe < Muroran > Sapporo, 180 km

- Uetsu Shinkansen ( 羽 越 新 幹線 ): Toyama < Joetsu - Nagaoka - Niigata - Akita> Aomori, 560 km

- Ōu-Shinkansen ( 奥 羽 新 幹線 ): Fukushima <Yamagata> Akita, 270 km

- Hokuriku-Chūkyō-Shinkansen ( 北 陸 ・ 中 京 新 幹線 ): Nagoya <> Tsuruga, 50 km

- San'in-Shinkansen ( 山陰 新 幹線 ): Osaka < Tottori - Matsue > Shimonoseki , 550 km

- Trans-Chūgoku-Shinkansen ( 中国 横断 新 幹線, Chūgoku Ōdan Shinkansen ): Okayama <> Matsue, 150 km

- Shikoku Shinkansen ( 四 国 新 幹線 ): Osaka < Tokushima - Takamatsu - Matsuyama > Ōita , 480 km

- Trans-Shikoku Shinkansen ( 四 国 横断 新 幹線, Shikoku Ōdan Shinkansen ): Okayama < Kōchi > Matsuyama, 150 km

- East Kyushu Shinkansen ( 東 九州 新 幹線, Higashi-Kyushu Shinkansen ): Fukuoka <Ōita - Miyazaki > Kagoshima, 390 km

- Trans-Kyūshū Shinkansen ( 九州 横断 新 幹線, Kyūshū Ōdan Shinkansen ): Ōita <> Kumamoto, 120 km

Aborted projects

- Narita Shinkansen ( 成 田 新 幹線 ): Tokyo <> Narita Airport , 40 miles. Construction began in 1974, but construction work had to be stopped in 1983 due to massive protests by the landowners along the planned route. In 1987 the plans were officially abandoned. Some preliminary construction work for the route is now being used by the Keisei Narita airport line.

Types

| Train type | construction year |

society | Vmax in operation |

Performance 1 |

Length 1 |

Number of cars | Number of trains |

route | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Series 0 | 1964 | JNR (1964-1987) JR Central, West |

220 km / h | 11.84 MW | 400.3 m | 16: 1971-1999, 12: 1964-2000 6: 1985-2008, 4: 1997-2001 |

3,216 cars |

Tōkaidō: 1964–1999, San'yō: 1972–2008 | |

| 100 series | 1985 | JNR (1985-1987) JR Central, West |

230 km / h 2 | 11.04 MW | 402.1 m | 16 with 2 or 4 double-decker cars: 1985–2004, 6: 2002-2012, 4: 2000–2011 |

66 | Tōkaidō: 1986-2003, San'yō: 1986-2012 | |

| 200 series | 1980 | JNR (1980-1987) JR East |

240 km / h 3 | 12.88 MW | (400 m) | 16 with 2 double-decker cars: 1991–2004 12: 1980–2007, 10: 2004-2013, 8: 1988–2000 |

66 | Tōhoku (Tokyo – Morioka): 1982-2011, Jōetsu: 1982-2013 | |

| 300 series | 1992 | JR Central, West | 270 km / h | 12.0 MW | 402.1 m | 16 | 70 | Tōkaidō: 1992–2012, San'yō: 1993–2012 | |

| Series E1 | 1994 | JR East | 240 km / h | 9.84 MW | 302.0 m | 12 (continuously two-story) | 6th | Tōhoku (Tokyo – Morioka): 1994–1999, Jōetsu: 1994–2012 | |

| Series E2 | 1995 | JR East | 275 km / h | 9.6 MW | 251.4 m | 10: 2002–, 8: 1995– | 53 | Tōhoku: 1997–, Nagano: 1997–2017, Jōetsu: 1998–2004, 2012– | |

| 500 series | 1996 | JR West | 300 km / h 4 | 5 18.24 MW | 404.0 m | 16: 1996–2010, 8: 2008– | 9 | Tōkaidō: 1997–2010, San'yō: 1997– | |

| Series E4 | 1997 | JR East | 240 km / h | 6.72 MW | 201.0 m | 8 (continuously two-story) | 26th | Tōhoku (Tokyo – Morioka): 1997–2005, (Tokyo – Sendai): 2005–2012, Jōetsu: 2001– | |

| Series 700 | 1997 | JR Central, West | 285 km / h | 13.2 MW | 404.7 m | 16: 1997-2020, 8: 2000- | 91 | Tōkaidō: 1999–2020, San'yō: 1999– | |

| N700 series | 2005 | JR Central, West, Kyushu |

300 km / h | 17.08 MW | 404.7 m | 16: 2005–, 8: 2008– | 163 | Tōkaidō: 2007–, San'yo: 2007–, Kyūshū: 2011– | |

| 800 series | 2004 | JR Kyushu | 260 km / h | 6.6 MW | 154.7 m | 6th | 9 | Kyushu: 2004– | |

| Series E5 | 2009 | JR East | 320 km / h 6 | 9.96 MW | 253.0 m | 10 | 37 (59) | Tōhoku: 2011– | |

| Series E7 | fall 2013 | JR East | 260 km / h | 12 MW | 12 | 18th | Hokuriku: 2014– | ||

| W7 series | Spring 2014 | JR West | 260 km / h | 12 MW | 12 | 11 | Hokuriku: 2015– | ||

| Series H5 | 2014 | JR Hokkaidō | 320 km / h | 10 | 4th | Hokkaidō: 2016– | |||

| Mini Shinkansen | |||||||||

| 400 series | 1990 | JR East | 240 km / h 7 | 5.04 MW | 148.0 m | 7 (6: 1990-1994) | 12 | Tōhoku (Tokyo – Fukushima): 1992–2010, Yamagata: 1992–2010 | |

| Series E3 | 1995 | JR East | 275 km / h 7 | 6.0 MW | 128.2 m | 0 series: 6 (5: 1995–1998) 1000/2000 series: 7 |

41 | 0 series: Tōhoku (Tokyo – Morioka): 1997–, Akita: 1997– 1000/2000 series: Tōhoku (Tokyo – Fukushima): 1999–, Yamagata: 1999– |

|

| Series E6 | 2010 | JR East | 320 km / h 7 8 | 6.0 MW | 148.7 m | 7th | 21 (24) | Tōhoku (Tokyo – Morioka): 2013–, Akita: 2013– | |

| JR Maglev | |||||||||

| Series L0 | 2013 | JR Central | 603 km / h | Max. 392 m | Max. 14th | 4 end cars, 10 middle cars | Extended Yamanashi test route ( Chūō-Shinkansen ) | ||

- 1 With the maximum number of cars

- 2 Only with V variant on the San'yō route; otherwise only passable at 220 km / h

- 3 1990-2000: 275 km / h only in the Dai-Shimizu tunnel on the Jōetsu route

- 4 Since 2010 only with a top speed of 285 km / h

- 5 The sets W2 to W9 only had 17.60 MW

- 6 Until the beginning of 2013 only with a top speed of 300 km / h.

- 7 Only with a maximum speed of 130 km / h on the Akita and Yamagata routes.

- 8 Until the beginning of 2014 only with a top speed of 300 km / h

It can be coupled:

- Class 200 (8 cars) + Class 400 (7 cars) (1992–1997)

- Class 200 (10 cars) + Class 400 / E3 (7 or 6 cars) (1997-2001)

- Class E4 (8 cars) + Class 400 (7 cars) (1999-2010)

- Class E4 (8 cars) + Class E3 (7 cars) (1999–)

- Class E2 (10 cars) + Class E3 (6 cars) (1999–)

- Class E4 (8 cars) + Class E4 (8 cars) (1997–)

- Class E5 (10 cars) + Class E3 (6 cars) (2011–)

- Class E5 (10 cars) + Class E6 (7 cars) (2013–)

Prototypes

| Train type | operating years |

society | power | Vmax | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 series | 1962-1964 | JNR | 2.72 MW / 4-car train | 256 km / h | March 30, 1963 on test track (later Tōkaidō track) |

| Series 951 | 1968-1979 | JNR | 1.84 MW / 2-car train | 286 km / h | February 24, 1972 on the San'yō route |

| Series 961 | 1973-1990 | JNR | 6.6 MW / 6-car train | 319 km / h | December 7, 1979 on test track (later Tōhoku track) |

| Series 962 | 1979-1983 | JNR | 5.52 MW / 6-car train | Prototype of the 200 series | |

| 500-900 series (WIN350) | 1992-1996 | JR West | 7.2 MW / 6-car train | 350.4 km / h | August 8, 1992 on the San'yō route, prototype of the 500 series |

| Series 952/953 (STAR 21) 1 | 1992-1998 | JR East | 9-car train | 425 km / h | December 21, 1993 on the Jōetsu route |

| 955 Series (300X) | 1995-2002 | JR Central | 9.72 MW / 6-car train | 443 km / h | June 26, 1996 on the Tōkaidō route |

| Gauge Change Train GCT01-01 to -03 | 1998-2006 | JTRI | 3-car train | 300 km / h 130 km / h |

Re-trackable undercarriages |

| Series E954 ( FASTECH 360 S ) | 2005-2009 | JR East | 8.6 MW / 8-car train | 398 km / h | E5 series prototype |

| Series E955 ( FASTECH 360 Z ) | 2006-2008 | JR East | 6-car train | 405 km / h (technically approved) | E6 series prototype (mini Shinkansen type) |

| Gauge Change Train GCT01-201 to -203 | 2006-2013 | JTRI | 3-car train | 270 km / h 130 km / h |

Re-trackable undercarriages |

| Gauge Change Train, FGT-9001 through -9004 | since 2014 | JR Kyushu | 4-car train | 270 km / h 130 km / h |

Re-trackable undercarriages |

| Series E956 (ALFA-X) | from 2019 | JR East | 10-car train | 400 km / h | Test vehicle for continuous operation at 360 km / h between Tokyo and Sapporo |

- 1 The two series were coupled as a set: Cars 1-4 from the 952 series and cars 5-9 from the 953 series with a Jakobs bogie system.

JR East, JR West and JR Central also operate yellow-painted diagnostic trains based on the Shinkansen series (series 0 , 200 , 700 and E3 ) with the nickname Doctor Yellow , which check the condition of the high-speed lines at full speed.

Train names and vehicles

All Shinkansen trains have the following train names according to the different destinations, intermediate stops or vehicles. The trains operated with the E1 or E4 series are called Max (Multi Amenity eXpress) .

Tōkaidō / San'yō / Kyūshū Shinkansen

- Nozomi ( の ぞ み , dt. "Hope"): the fastest trains of the Tōkaidō and San'yō Shinkansen , which are operated with the N700 series (previously also served with the 300 , 500 and 700 series ).

- Mizuho ( み ず ほ , dt. "Fertile rice ear"): the fastest trains that have been operated since March 2011 between the stations Shin-Osaka on the San'yō-Shinkansen and Kagoshima-Chūō on the Kyūshū-Shinkansen with the N700 series.

- Hikari ( ひ か り , dt. "Light"): the fast trains of the Tokaido and San'yō Shinkansen, which do not stop at all stations. The N700 series is used for this (previously also the 0 , 100 , 300 and 700 series). The trains that only run on the San'yō Shinkansen are generally referred to as Hikari Rail Star ( ひ か り レ ー ル ス タ ー ) and operated with the 700 series.

- Sakura ( さ く ら , dt. " Cherry Blossom "): the fast trains of the Kyūshū Shinkansen as well as the trains passing through to and from the San'yō Shinkansen. Served with the N700 and 800 series (only on the Kyūshū Shinkansen).

- Kodama ( こ だ ま , dt. "Echo"): the trains stop at all stations of the Tokaido and San'yō Shinkansen, but no train goes through both Shinkansen, so you have to change trains. The trains are operated with the N700 series (previously also with the 0, 300 and 700 series). The 500 series is also used on the San'yō Shinkansen.

- Tsubame ( つ ば め , dt. " Swallows "): the trains only run on the Kyūshū Shinkansen and stop at all stations. Served with the 800 and N700 series.

Tōhoku / Yamagata / Akita Shinkansen

- Hayabusa ( は や ぶ さ , Eng. " Peregrine Falcon "): the fastest trains on the Tōhoku Shinkansen . Since March 2011, the E5 series has been running as the Hayabusa with a top speed of 320 km / h (300 km / h until 2013).

- Hayate ( は や て , dt. "Stormwind"): the fast trains on the Tōhoku Shinkansen that travel between the stations Ōmiya and Sendai without stopping. The series E2 , E5 and E3 (amplifier trolleys) are used.

- Komachi ( こ ま ち , dt. " Ono no Komachi "): Connection between Tokyo and Akita, which operates on the Tōhoku Shinkansen and Akita Shinkansen. It is operated with the E6 series . In principle, the trains between Tokyo and Morioka are operated in traction with the trains of the Hayate connection with a maximum speed of 320 km / h.

- Yamabiko ( や ま び こ , dt. "Bergecho"): the fast trains on the Tōhoku Shinkansen that do not stop at all stations. Yamabiko is served in traffic between Tokyo and Sendai or Morioka with the series E2, E3 and E5 (previously also with the series E1 , E4 and 200 ).

- Tsubasa ( つ ば さ , dt. "Wing"): the fast trains that connect Tokyo on the Tōhoku Shinkansen and Yamagata or Shinjō on the Yamagata Shinkansen . The trains are operated with the E3 series (until 2010 with the 400 series) and are generally coupled with Yamabiko between Tokyo and Fukushima .

- Nasuno ( な す の , dt. "Field in Nasu "): The trains commute between Tokyo and Nasu-Shiobara or Kōriyama on the Tōhoku-Shinkansen and stop at all train stations. They are operated with trains of the E2 and E3 series (previously also with the E4, 200 and 400 series).

Jōetsu- / Hokuriku (Nagano) shinkansen

- Toki ( と き , dt. " Japanese Ibis "): The trains are served between Tokyo and Niigata on the Jōetsu Shinkansen with the series E2 and E4 (earlier also with the series E1 and 200).

- Tanigawa ( た に が わ , dt. "Mountain Tanigawa"): The trains connect Tokyo and Takasaki or Echigo-Yuzawa (in winter further to Gāra-Yuzawa) on the Jōetsu-Shinkansen and stop at all stations. The E4 series is used.

- Asama ( あ さ ま , dt. "Volcano Asama "): the trains run between Tokyo and Kanazawa on the Jōetsu and Hokuriku Shinkansen . The E2 and E7 series operate as Asama (from 2001 to 2003 also the E4 series as additional trains between Tokyo and Karuizawa).

- Kagayaki (か が や き, dt. "Shine"): Express connection of the Hokuriku Shinkansen between Tokyo and Kanazawa. Trains from the E7 / W7 series are used.

- Hakutaka (は く た か, Eng. " Night Falcon "): Connection of the Hokuriku Shinkansen between Tokyo and Kanazawa, which stops at all train stations. Trains from the E7 / W7 series are used.

- Tsurugi (つ る ぎ, German " sword "): Shuttle connection of the Hokuriku Shinkansen between Toyama and Kanazawa. Trains from the E7 / W7 series are used.

Former train names

- Jōetsu Shinkansen

- Asahi ( あ さ ひ , dt. "Morning sun"): From 1982 to 2002 the fast trains between Tokyo and Niigata were called Asahi and operated with the 200, E1, E2 and E4 series.

- Tōhoku Shinkansen

- Aoba ( あ お ば , dt. "Castle Aoba"): From 1982 to 1997 the trains between Tokyo and Nasu-Shiobara or Sendai were operated with the series 200, 400, E1 and E2 and stopped at all stations.

- Super-Komachi ( ス ー パ ー こ ま ち ): Connections between Tokyo and Akita, which operated from 2013 to 2014 with the E6 series and was about 5 minutes faster than the Komachi connections. After the complete retirement of the E3 series, the connection was renamed back to Komachi .

technology

Since the Shinkansen trains exceed an operating speed of 200 km / h on most of the routes, a technology that deviated from conventional routes was necessary. Regardless of the speed, driving comfort and safety are kept at a high level. The success of this technology was an impetus in many countries beyond Japan to rethink the role of rail transport.

Route and track system

The Shinkansen routes (except mini-Shinkansen) are new lines and separate from the rest of the rail network. They are standard gauge (1435 mm). Basically, the track spacing is 4.3 meters, the minimum curve radius is 4000 meters and the maximum gradient is 15 per mille (Law of the Ministry of Transport No. 39 in 2000). The low standard was created on the first Tōkaidō route that was built. The larger standard (wider curves and steeper incline) is included in the newly built sections of the routes.

- The curve radius increases; on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen it is 2500 m (maximum speed 255 km / h). All routes since the San'yō Shinkansen basically have a curve radius of more than 4000 m, so that they can be driven through at the current maximum speed of 300 km / h without braking. However, due to basic and terrain restrictions, this possibility does not exist on all routes, at that time the legally permitted minimum permitted curve radius (Law of the Ministry of Transport No. 70 in 1964) was 400 m. Within the metropolitan areas (e.g. between the stations Tokyo and Ōmiya on the Tōhoku Shinkansen and Tokyo and Shin-Yokohama on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen) the Shinkansen routes were built parallel to the conventional routes. A narrower curve radius was also chosen in the arrival and departure areas of the main train stations and in the area of some other through stations and tunnels.

- When the Tōkaido Shinkansen was only built with a gravel superstructure because of the low construction costs , accidents often happened in the winter. Ice blocks adhering to the trains fell onto the gravel and damaged train windows and equipment under the train. For this reason, a slab track is used on the lines that were built later . In some regions with heavy snowfall, the sprinkler systems on the Tōkaidō, Tōhoku and Jōetsu Shinkansen and the concrete snipers on the Tōhoku, Jōetsu and mini Shinkansen are installed.

- The maximum speed of each section of the Shinkansen is also limited according to the noise standard in the Ministry of Environment Act (Act No. 46 of 1970). This standard requires less than 70 or 75 dB at the location with a distance of 20 meters from the route axis for the train journey . For example, the maximum speed between Ōmiya and Utsunomiya stations on the Tōhoku Shinkansen is limited to up to 240 km / h.

- In order to increase driving comfort and safety as well as to reduce noise pollution, various adjustments were made to the rails and switches. To reduce the number of joints, particularly long 25 m individual rails were laid and welded. On the Tōhoku Shinkansen, between Numakunai and Hachinohe stations, there is a 60.4 km section. In order to pass through at a higher speed, the points with a movable frog were used. The maximum permissible speed of the turnouts for the branching track is 160 km / h (e.g. at a junction from the Jōetsu Shinkansen to the Hokuriku Shinkansen near the Takasaki station).

- On some sections of the lines, three - rail tracks will be expanded due to joint operation with freight and local transport (e.g. Akita Shinkansen ). It was dismantled on the Yamagata Shinkansen in 1998 after goods traffic there was taken out of service. A three-rail track was installed on the Hokkaido Shinkansen over a length of about 82 km, including the Seikan tunnel .

- For the mini Shinkansen routes to Yamagata and Akita , the gauge of the old routes has been increased from 1067 mm to 1435 mm (standard gauge). On the old lines, the trains only reach a maximum of 130 km / h. However, this maximum speed cannot be extended everywhere due to the many relatively tight bends and the high gradients. According to the law that regulates railway operations (Law of the Ministry of Transport No. 15 in 1989), the braking distance for emergency braking on old lines should be shorter than 600 meters and the maximum speed was limited to 130 km / h. After the abolition of this law in 2002, the maximum speed will not be increased because of the safety at level crossings and the tight curves. A higher speed on mini Shinkansen routes requires the high construction costs of the further double-track expansion with the new tunnels and overpasses.

To avoid personal accidents, the following measures have been taken:

- To avoid collisions with motor vehicles, level crossings were completely avoided, with the exception of the mini-Shinkansen, which sometimes runs on old routes. On the latter, only the number of level crossings was reduced and the safety technology improved.

- The entire rail area was made inaccessible to people, mainly by separating the level of the track. The penalties for obstructing rail traffic have also been tightened by a special regulation for the Shinkansen compared to conventional rail traffic.

- To avoid accidents caused by contact with through trains, platforms have been fitted with movable barriers or through traffic has been directed to sidings (with some exceptions for stations with little or no through traffic such as Nagoya or Ōmiya).

Signal systems

- At high speeds it is not possible to recognize signals attached to the route from the driver's cab . The Shinkansen was therefore equipped with an automatic ATC train control system, which displays the maximum permitted speed in a block as a signal in the driver's cab. Due to the increase in speed, the analog ATC system, which originally comprised six speed levels up to 210 km / h, was later expanded to twelve levels up to 300 km / h. From 2001 a new digital ATC system was gradually introduced on Tōkaidō, Tōhoku, Jōetsu and Kyūshū routes in order to reduce travel time and shorten train headways. The new technology also made it possible, instead of block-related (rigid) maximum speeds, to lead trains to the stopping point at a dynamically decreasing speed. The information on standstill points and the line locations with limited speeds (e.g. curves and switches) are transmitted as signals over the rails.

- The running status of all trains is controlled by the centralized traffic control (CTC) of the route control center and points and signals are set. From the 1990s, the new PTC (Programmed Traffic Control) train control system was introduced to coordinate CTC, platform information, maintenance of trains and the creation of special timetables in the event of traffic disruptions.

Power supply

- The 25 kV single-phase alternating current network is operated with the following frequencies: (Note: In Japan there are two regionally separate electricity networks with different frequencies, but the same voltage of 100 V in the house network and 220 V in the three-phase network, e.g. in Tokyo 50 Hz and Osaka 60 Hz)

- The Tokaidō Shinkansen is uniformly supplied with 60 Hz. In Shizuoka Prefecture , the 50 Hz to 60 Hz AC frequency limit is exceeded. The respective route sections with the same alternating current frequency were designed to be as long as possible, with the aim of simplifying the vehicle technology. This requires the frequency in areas with a 50 Hz power supply to be changed to 60 Hz to supply the Shinkansen.

- The transition between 50 Hz and 60 Hz for the Hokuriku Shinkansen is near Karuizawa .

- Notwithstanding the above, the regional Shinkansen routes are operated with the local AC frequency. The San'yō-Shinkansen (as an extension of the Tōkaidō-Shinkansen) and the Kyūshū-Shinkansen with 60 Hz, the Tōhoku-Shinkansen and the Jōetsu-Shinkansen with 50 Hz.

- The mini Shinkansen, which is operated on the Yamagata and Akita lines partly on old lines with 50 Hz, 20 kV and partly on new Shinkansen lines, is therefore designed for multi-system power supply.

Vehicle technology

- The trains have no powered end cars - the drive units are distributed under the floor over the length of the train. This system has higher acceleration and braking performance, is lighter and puts less strain on the track body. This reduces the construction and maintenance costs of the lines on the soft Japanese soil. In the event of technical problems, the corresponding drive unit is switched off without affecting the entire train (with a switched off drive unit, 160 km / h can be achieved on a 25 per mil gradient). Since this system has exceptionally high procurement and repair costs, it has made exports considerably more difficult. Most recently, Taiwan (2007) decided to use the Shinkansen. Korea, on the other hand, which was temporarily considering the use of Shinkansen technology for the Korea Train Express , uses TGV technology.

- The Shinkansen wagons are 25 meters long and, at 3.38 meters, significantly wider than European high-speed trains, so that a higher seating capacity is achieved with the same length. The wagons of the mini Shinkansen trains, which also run on old lines with a narrower clearance profile , are basically 20 meters long and at 2.95 meters only as wide as the trains in Europe. If such a train stops at the station on a new line, running boards are folded out to compensate for the distance between the platform edge and the narrow car body .

- The series 0 had a pantograph for each drive unit . When the maximum speed was increased, the pantographs separated from the contact wire more frequently, arcing ; this led to noise and often damaged the overhead contact line and pantographs. In order to reduce the formation of switching arcs when a pantograph jumps off, all pantographs on the newer Shinkansen trains have been electrically connected to a high-voltage line on the roof, so that only two or three pantographs need to be raised. This measure reduced the noise from the pantographs. With new technology (improvement of the pantograph contact strip ), the latest Shinkansen series E5 and E6 can run with just one pantograph.

- For a high drive power, the proportion of driven cars in the train set is very high. In the first generation of the 0 series used on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen and the 200 series originally used in the Tōhoku Shinkansen and Jōestu Shinkansen, all cars are powered. Also in the series 500 (due to the high acceleration for the extension of the travel time traveled at 300 km / h) and in the Kyūshū Shinkansen series 800 (due to the high gradient) all cars are driven again.

- The hallmark of the Shinkansen trains is the aerodynamic train design with an elongated, nose-like bow shape. This counteracts the tunnel bang that can occur when driving through the narrow tunnels that are common in Japan. Due to the increase in the top speed from 210 km / h to 320 km / h, the bow length, which was originally 4.5 meters for the first Shinkansen generation of the 0 series, was extended to 15 meters for the newer generations of the E5 and E6 series.

- The carriages are designed to be airtight so that the pressure fluctuations that occur when entering the tunnel at high speed do not restrict travel comfort.

- The latest Shinkansen generations have tilting technology with the control of the air pressure in the secondary springs of the bogie. The N700 series tilts up to one degree. This allowed the maximum speed in curves of the Tokaido route (2,500 m standard radius) to be increased from 255 km / h to 270 km / h. The series E5 and E6 incline by 1.5 degrees in order to negotiate curves with radii of 4,000 meters on the Tohoku route at 320 km / h, although the prototype trains of these series (FASTECH 360) move 2 degrees for the planned maximum speed of Could tilt 360 km / h.

Accidents

From the start of operations in 1964 until today, there have been no fatal accidents:

- The worst accident in the history of the Shinkansen occurred in an earthquake measuring 6.8 on the Richter scale on October 23, 2004 at 5:56 p.m. local time. Despite an automatically initiated emergency braking, the Toki 325 train to Niigata with 155 passengers derailed between the Urasa and Nagaoka stations . The train quickly came to a standstill as the Shinkansen has had an earthquake early warning system since 1998 . (If an earthquake is registered, the power automatically switches off and the Shinkansen initiates an automatic emergency braking system.) Eight of the ten cars derailed. Although there were no injuries, the powered end car protruded so far into the neighboring track that, in the worst case, a collision with an opposing train could have occurred. It was the only time so far that a Japanese high-speed train derailed in passenger service.

- On a service trip on February 21, 1973 at 5:30 p.m., a class 0 train, which was traveling from the Osaka depot to the main line of the Tōkaido Shinkansen at 25 km / h, derailed. The engine driver noticed an absolute stop signal too late and the train stopped with a destruction of the switch on the main line. Without knowing the condition of the train, the dispatcher gave the instruction to drive back and the train derailed on the switch without personal injury. The train protection enabled a train (Kodama 142) with a speed of 200 km / h to stop 467 meters from the scene of the accident. At the absolute stop signal of the Automatic Train Control (ATC), the train should stop in front of the turnout because of the automatic rapid braking. After the accident, an additional track magnet was installed in front of the signal coil of the absolute stop signal and the number of signal coils was doubled. A more suitable lubricant for wheel flange lubrication was also used.

- The third accident with train derailment occurred in the Tōhoku earthquake in 2011 with a magnitude of 9.0 on March 11, 2011 at 14:46. Although the section of the Tohoku Shinkansen between the stations Omiya and Iwate-Numakunai with a length of over 500 km at a total of 1200 points (the overhead lines at 470 points, the pillars at 100 points, the superstructures at 22 points, the shear of the concrete bridges 2 places and the ceiling of the five stations) was damaged, only one E2 series train (one bogie of the fourth car) derailed during the test drive near Sendai station without personal injury. The route between Sendai and Ichinoseki stations was interrupted for 50 days until April 28th.

- So far, the Shinkansen routes have been destroyed twice without train damage due to major earthquakes. The first accident of this type occurred on April 20, 1965 in a 6.1 magnitude earthquake near the Ōi River in Shizuoka Prefecture . Although part of the superstructure of the Tokaido Shinkansen in the city of Shizuoka and the surrounding area fell apart, only two trains per hour ran at that time and all trains stopped immediately after the earthquake by CTC without train problems.

- The second accident occurred in the Kobe earthquake with a magnitude of 7.3 on January 17, 1995 at 05:46 local time. Some concrete bridges, pillars and inner walls of the San'yō Shinkansen tunnels crumbled and the line between Shin-Osaka and Himeji stations was interrupted for 80 days until April 8th. Due to the shutdown of the Shinkansen between midnight and 6 a.m., there was no train at this time. After this earthquake, an earthquake early warning system was installed on April 28, 1995 on San'yō Shinkansen. In addition, the permitted braking distance for rapid braking has been shortened; so the planned top speed of 320 km / h of the 500 series on the San'yō route could not be achieved.

- On April 25, 1966 around 7 p.m., the second axle of the last car from a class 0, which was traveling as Hikari 42 from Shin-Osaka to Tokyo, between Nagoya and Toyohashi on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, broke. Although the broken axle stuck to the axle box, the train did not derail and there was no personal injury. The material of the wheelset shaft had insufficient stability due to a power failure during production.

- On September 30, 1991 a wheel of an X-set of the series 100 (Hikari 291 to Shin-Osaka) blocked on the Tōkaido Shinkansen route. Due to an oil leak, the drive of car 15 was damaged and a second wheel of the car blocked. Although the alarm sounded in the driver's cab immediately upon exiting Tokyo station, the train was ordered by the dispatcher to travel to Mishima station (approx. 100 km from Tokyo) at the maximum speed of 225 km / h approved by the train protection. Part of the wheel was deformed to a length of 30 cm and a depth of up to 3 cm (total weight approx. 6 kg). After this accident it was added to the inspection manual that it must be checked that all wheels are free to move.

- On June 27, 1999 fell in the Fukuoka tunnel on the San'yō route four concrete lumps (about 200 kg weight) on a 220 km / h fast train of the 0 series (Hikari 351 to Hakata). The roof of this train (air conditioning and two pantographs) was damaged - without personal injury - over a length of sixteen meters, as was the overhead line. Incidents with falling concrete lumps were repeated several times in tunnels on the San'yō route (e.g. on October 9, 1999 in the north Kyūsyū tunnel).

Shinkansen technology worldwide

In August 2004, the Chinese government signed a contract with six Japanese companies (including Kawasaki Heavy Industries ), which in cooperation with the Chinese locomotive manufacturer Nanche Sifang ("China Southern Locomotive and Rolling Stock Industry") will use Shinkansen technology on five routes with a total length of about 2000 km in the People's Republic. A modified version of the Japanese Shinkansen is to be implemented with a top speed of 275 km / h and an average speed of around 200 km / h.

The Taiwan High Speed Rail trains have been using Shinkansen technology on the island of Taiwan between Taipei and Kaohsiung since 2007 .

Fares

The Shinkansen fares generally consist of a basic price and a surcharge, whereby the surcharge is often exactly as high as the basic price. Both prices are calculated according to the kilometers traveled. Fares can be reduced by 10-20% when using multi-trip tickets, special offers or zone tickets, but there is no Bahncard or saver fares like in Germany.

See also

literature

- Helmut Petrovitsch: The Shinkansen high-speed network in Japan . In: Eisenbahn-Revue International . 8 and 9, 2002, ISSN 1421-2811 , pp. 320-330 and 372-378 .

- Peter Semmens: Shinkansen - The world's busiest high-speed railway . Platform 5 Publishing, 1997, ISBN 1-872524-88-5 .

- Anthony Coulls: Railways as World Heritage Sites. ICOMOS , 1999, p. 22 f. (= Occasional Papers of the World Heritage Convention)

- Wilfried Wunderlich: 50 years of Shinkansen . Japan's high-speed rail traffic today. In: Railway courier . No. 11 , 2014, ISSN 0170-5288 , p. 76-79 .

- Helmut Petrovitsch: 50 years of Shinkansen . Japan's fast trains. In: Eisenbahn Magazin . No. 10 , 2014, ISSN 0342-1902 , p. 6-14 .

items

- Ernst Schnabel , photos: Paul Chesley: Japan's super express: The bullet. In: Geo-Magazin. Hamburg 1980,3, pp. 102-114. Informative experience report. ISSN 0342-8311

Web links

- Shinkansen. In: high-speed trains.com

- "Chūō-Shinkansen" (Linear Motor Car; Maglev) - test track in Yamanashi Prefecture

- JR KYUSHU - Tsubame 800

Individual evidence

- ^ Announcement of the corrigendum to issue 12/2004 . In: Eisenbahn-Revue International , issue 2/2005, ISSN 1421-2811 , p. 80.

- ↑ Message for the first time Shinkansen derailed . In: Eisenbahn-Revue International , issue 12/2004, ISSN 1421-2811 , p. 570.

- ↑ a b Moshe Givoni: Development and Impact of the Modern High Speed Train: A Review . In: Transport Reviews . 26, No. 5, Jahr, ISSN 0144-1647 , pp. 593-611

- ↑ 東海 道 新 幹線 写真 ・ 時刻表 で 見 る 新 幹線 の 昨日 ・ 今日 ・ 明日 (Tōkaidō Shinkansen) . JTB Neko Publishing, Japan 2000, ISBN 4-533-03563-9 , p. 54

- ↑ An ICE of the Extrabreit type in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung from November 29, 2005

- ↑ Announcement 25 years of Shinkansen . In: Eisenbahntechnische Rundschau , 38 (1989), issue 12, p. 790 f.

- ↑ Announcement of the double-decker coach for Shinkansen completed . In: Railway technical review . 34, No. 7/8, 1985, p. 512.

- ↑ Siemens.com: Siemens keeps high speed with high-speed trains - Velaro ensures short travel times in Spain and soon also in China and Russia. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Erlangen, March 18, 2008.

- ^ Nationwide Shinkansen Railway Development Act. (PDF; 77 kB) MLIT, accessed on December 16, 2010 (English, full text).

- ↑ Construction of the Shinkansen tracks in the Seikan tunnel (Japanese) ( Memento of the original from December 18, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Article in the Mutsu-Shinpō newspaper on November 21, 2009

- ↑ JRTT: 九州 新 幹線 西 九州 ル ー ト 武雄 温泉 ・ 諫 早間 建設 工事 (PDF; 337 kB). Press release of April 3, 2008

- ↑ Japanese Ministry of the Country, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Permission to build Chuo Shinkansen (中央 新 幹線 の 整 備 計画 の 決定) (PDF; 130 kB). Press release from May 26, 2011

- ^ Railway Gazette: Work starts on Chuo maglev. December 18, 2014 (English)

- ↑ 北海道 新 幹線 札幌 延伸 に 伴 う 効果 と 地域 の 課題 調査 報告 書 (要約 版). (PDF; 1.0 MB) Hokkaidō Economic Union from July 2006, p. 2

- ↑ a b c 高速 鉄 道 物語 - そ の 技術 を 追 う - (narration of high-speed traffic). Seizandō Syoten, Japan 1999, ISBN 4-425-92321-9 , p. 125.

- ↑ a b c d 鉄 道 の テ ク ノ ロ ジ ー Vol.1 新 幹線 (Technology of the railroad Shinkansen) . Sanei Syobō, Japan 2009, ISBN 978-4-7796-0534-5 , p. 85

- ↑ JR 電車 編成 表 2013 冬. November 2012. p. 10. ISBN 978-4-330-33112-6 .

- ↑ a b c JR East: 東北 新 幹線 に お け る 高速 化 の 実 施 に つ い て (PDF; 14 kB). Press release from November 6, 2007

- ↑ 鉄 道 の テ ク ノ ロ ジ ー Vol.6 国 鉄 新 性能 電車 (Technology of the Railway) . Sanei Syobō, Japan 2010, ISBN 978-4-7796-0864-3

- ↑ a b c JR East: 新型 高速 新 幹線 (E6 系) 量 産 先行 車 に つ い て (PDF; 175 kB). Press release from February 2, 2010

- ↑ Shinichiro Tajima: Development of the Shinkansen series E5 (Japanese). JR East Technical Review No. 31, Japan Spring 2010. p. 12

- ↑ Series 500 . JR West website (JR お で か け ネ ッ ト) Shinkansen-Kodama (Japanese)

- ↑ JR East: 新型 高速 新 幹線 車 両 (E5 系) の デ ザ イ ン に つ い て (PDF; 105 kB). Press release from February 3, 2009

- ↑ JR East: 東北 新 幹線 は や ぶ さ に 投入 し て い る E5 系 車 両 を は や て 、 や ま び こ に 導入 . Press release from September 12, 2011

- ↑ a b c d プ ロ ト タ イ プ の 世界 (world of the prototype). Kōtsū Shimbunsha, Japan December 2005.

- ↑ FASTECH 360 新 幹線 電車 用 駆 動 装置 ・ 集 電 装置東洋 電機 技 報 No. 114, Toyo Denki, Sep 2006. ( Memento of the original from June 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked . Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 264 kB)

- ↑ a b JR Kyūshū: timetable change in spring 2011 ( memento of the original from December 20, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Japanese). Press release from December 17, 2010.

- ↑ a b JR East: timetable change on December 1, 2002 (Japanese). Press release from September 20, 2002. p. 6.

- ↑ Mainichi Shinbum: "秋田 新 幹線: 新型 列車 名「 ス ー パ ー こ ま ち 」に…" ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . November 6, 2012, Japanese

- ↑ a b Dankichi Takahashi: 新 幹線 を つ く っ た 男 、 島 秀雄 物語 (story of Hideo Shima, the man who built the Shinkansen). Syōgaku-kan, Japan 2000, ISBN 4-09-341031-3 .

- ↑ Noise standard . Japan Ministry of the Environment website, Shinkansen Train Noise Environmental Standard (Japanese)

- ↑ Seikan Tunnel ( Memento of the original from April 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . JR Hokkaido Website, Seikan Tunnel (Japanese)

- ↑ Expansion plan for the Yamagata Shinkansen . Yamagata Prefecture Website (Japanese)

- ↑ デ ジ タ ル ATC の 開 発 と 導入 (development and introduction of the digital ATC system) . JR East Technical Review No. 5, Japan 2003, pp. 27-30.

- ^ About the Shinkansen . JR Central website.

- ↑ 復 刻 増 補 版 新 幹線 0 系 電車 (Shinkansen series 0 extended edition). Ikaros Publishing House, Japan 2008, ISBN 978-4-86320-123-1 .

- ↑ 鉄 道 フ ァ ン (Railway Fun) No. 389, Shinkansen class 100. Kōyū-sya, Japan September 1993.

- ↑ 360 新 幹線 電車 用 駆 動 装置 ・ 集 電 装置 ( Memento of the original from June 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . 東洋 電機 技 報 No. 114, Toyo Denki, Sep 2006.

- ↑ Series E5 ( Memento of the original from November 3, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . JR East website, My name is Hayabusa (Japanese)

- ↑ N700 series . JR Central website, Shinkansen N700 series (Japanese)

- ↑ JR East: 東北 新 幹線 に お け る 高速 化 の 実 施 に つ い て (PDF; 286 kB). Press release from March 9, 2005

- ↑ Kazuya Kioth, Tetsu Nagasawa, Koichiro Mizuno, Hiroyuki Osawa: Earthquake Early Warning System at JR-East . In: Japanese Railway Engineering . No. 203 , 2019, ISSN 0448-8938 , p. 15-17 .

- ↑ Kunio Yanagida: 新 幹線 事故 (Accidents of the Shinkansen). Chūkō-sinsyo 461, Chūō-kōron-shinsya, Japan 1977, ISBN 978-4-12-100461-1 , pp. 2–119.

- ↑ JR East: 東北 新 幹線 の 地上 設備 の 主 な 被害 と 復旧 状況 (PDF; 533 kB). Press release from March 28, 2011

- ↑ [ http://www.asahi.com/national/update/0314/TKY201103140488.html ( Memento from March 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) 鉄 路 も 断 た れ た 仙台 駅 、 復旧 の め ど 立 た ず ] In: Asahi Shinbun . March 14, 2011.

- ↑ 東北 新 幹線 全線 が 復旧 、 震災 50 日 、 初 の 列島 横断 In: 47 NEWS. April 29, 2011.

- ↑ 県 内 を 襲 っ た 主 な 地震 (Great Earthquake in Shizuoka Prefecture) . Shizuoka Newspaper Archives website, Japan, 2010.

- ↑ 阪神 ・ 淡 路 大 震災 教訓 情報 資料 集 (instruction and collection of information from the 1995 earthquake in Kobe) ( memento of the original from June 29, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Cabinet Office website, Government of Japan, 2006.

- ↑ 鉄 道 ジ ャ ー ナ ル (Railway Journal) No. 344. Railway Journal, Japan June 1995, p. 73.

- ↑ 鉄 道 ジ ャ ー ナ ル (Eisenbahn Journal) No 499. Railway Journal, Japan May 2008, ISSN 0288-2337 , p. 45.

- ↑ Jun Sakurai: 新 幹線 「安全 神話」 が 壊 れ る 日 (The Day Lost the Security Myth of the Shinkansen). Kōdan-sya, Japan 1993, ISBN 4-06-206313-1 , pp. 38-41.

- ↑ 山陽 新 幹線 ト ン ネ ル 安全 総 点 検 (Inspection of the San'yō Shinkansen tunnels) . リ テ ッ ク vol. 3, Japan 2000, pp. 34-39. In 非 破 壊 試 験 法 に よ る コ ー ル ド ジ ョ イ ン ト の 評 価 に 関 す る 研究 (Materials testing technology on the estimation of the cold joint) Kōei-Forum Vol.9, Japan January 2001, p. 117.

- ↑ Oliver Mayer: The tariff system of the Japanese railways. In: The Bulletin of Aichi University of Education, Humanities, Social Sciences. No. 58, 2009, pp. 185-192. Full text of the article.