Chinese languages

The Chinese or Sinitic languages ( Chinese 漢語 / 汉语 , Pinyin Hànyǔ ) form one of the two primary branches of the Sino- Tibetan language family , the other primary branch is the Tibetan-Burman languages . Chinese languages are spoken by approximately 1.3 billion people today, most of whom live in the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan) . There are major Chinese-speaking minorities in many countries, especially in Southeast Asia . The Chinese language with the largest number of speakers is Mandarin . On it based high Chinese that simply "the Chinese" or "Chinese" is called.

| Chinese languages | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | 1.3 billion native speakers (estimated) |

|

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

zh |

|

| ISO 639 -2 | ( B ) chi | ( T ) zho |

| ISO 639-3 |

zho |

|

| ISO 639 -5 |

zhx |

|

Several Chinese languages, one Chinese script

As a rule, the term “Chinese language” refers to the standard language Standard Chinese ( 普通話 / 普通话 , Pǔtōnghuà in China, 國語 / 国语 , Guóyǔ in Taiwan), which is based on the largest Sinitic language, Mandarin ( 官 話 / 官 话 , Guānhuà ) and essentially corresponds to the Mandarin dialect of Beijing ( 北京 話 / 北京 话 , Běijīnghuà ). There are also nine other Chinese languages, which in turn break down into many individual dialects. These are called "dialects" in European languages, although the degree of their deviation from one another would justify classification as a language according to western standards. In traditional Chinese terminology, they are called fangyan ( 方言 , fāngyán ).

Even within a large Sinitic language, speakers of different dialects can not always be understood, especially the northeastern dialect ( 東北 話 / 东北 话 , Dōngběihuà , 東北 方言 / 东北 方言 , Dōngběi Fāngyán ) and the southern dialects ( 南方 話 / 南方 话 , Nánfānghuà , 南方 方言 / 南方 方言 , Nánfāng Fāngyán ) of the Mandarin are not mutually understandable. In China, standard Chinese, spoken by most of the Chinese, is predominantly used to communicate across language borders; Other languages such as Cantonese also serve as a means of communication in a more regionally limited manner .

The Chinese writing also functions to a limited extent as a cross-dialect means of communication, since etymologically related morphemes are generally written in all dialects with the same Chinese character, despite different pronunciation. Let the following example illustrate this: In Old Chinese, the common word for "eat" * was Ljɨk , which was spelled with the character 食 . Today's pronunciation for the word “eat” shí ( Standard Chinese ), sɪk ˨ ( Yue , Cantonese dialect, Jyutping sik 6 ), st ˥ ( Hakka , Meixian dialect), sit ˦ ( Southern Min , Xiamen dialect ) all come from this and are therefore also written 食 .

Thus, the logographic Chinese script - each character in principle stands for a word - serves as a unifying bond that connects the speakers of the very different Chinese language variants to a large cultural community with a millennia-old written tradition. This unifying function would not exist in an alphabet or any other phonetic transcription.

However, this does not mean that the Chinese dialects only differ phonologically. In standard Chinese, for example, “to eat” is not usually used as shí , but rather chī , which does not come from * Ljɨk and is therefore written with its own character, 吃 , chī . The dialects of Chinese, if they are written, have their own characters for many words, such as Cantonese 冇 , mǎo , Jyutping mou 5 , mou ˩˧, “not have”. Because of this, but also due to grammatical discrepancies, even written texts can only be understood to a limited extent across dialects.

Until the beginning of the 20th century but the use of classical Chinese, its written form was dialect independent and has been used in China and Japan, Korea and Vietnam, at the level of practicing written language a unifying function.

Chinese languages and their geographical distribution

The original range of the Chinese language is difficult to reconstruct, since the languages of the neighbors of ancient China are almost unknown and therefore it cannot be determined whether Chinese languages were spoken outside the Chinese states that left written documents; large parts of southern China in particular seem to have been outside the Chinese-speaking area in the 1st century AD. Already in the time of the Zhou dynasty (11th to 3rd centuries BC) there are indications of a dialectal structure of Chinese, which became significantly stronger in the following centuries. Today, a distinction is usually made between eight Chinese languages or dialect bundles, each consisting of a large number of local individual dialects.

The following table shows the eight Chinese languages or dialect bundles with their number of speakers and main areas of distribution. The speaker numbers come from Ethnologue and other current sources. A detailed listing of local dialects can be found in the article List of Chinese Languages and Dialects .

| language | alternative name | speaker | Main distribution area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin | North Chinese dialects, Beifanghua ( 北方 話 / 北方 话 ), Beifang Fangyan ( 北方 方言 ) |

approx. 955 million | China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore |

| Wu | Wuyu ( 吳語 / 吴语 ), Wuyueyu ( 吳越 語 / 吴越 语 ), Jiangnanhua ( 江南 話 / 江南 话 ), Jiangzhehua ( 江浙 話 / 江浙 话 ) | approx. 80 million | China: Yangzi Estuary, Shanghai |

| Min | Minyu ( 閩語 / 闽语 ), Fujianhua ( 福建 話 / 福建 话 ) | approx. 75 million | China: Fujian, Hainan, Taiwan |

|

Yue / Cantonese |

Yueyu ( 粵語 / 粤语 ), Guangdonghua ( 廣東話 / 广东话 ), Guangzhouhua ( 廣州 話 / 广州 话 ), Guangfuhua ( 廣 府 話 / 广 府 话 ), rare: Baihua ( 白話 / 白话 ) | approx. 70 million | China: Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, Macau |

| Gan | Ganyu ( 贛 語 / 赣 语 ) | approx. 48 million | China: Jiangxi, Hubei; also Hunan, Anhui, Fujian |

| Jin | Jinyu ( 晉 語 / 晋 语 ) | approx. 48 million | China: Shanxi, Inner Mongolia; also Hebei, Henan |

| Kejia / Hakka | Kejiayu ( 客家 語 / 客家 语 ), Kejiahua ( 客家 話 / 客家 话 ) | approx. 48 million | China: South China, Taiwan |

| Xiang | Xiangyu ( 湘 語 / 湘 语 ), Hunanhua ( 湖南 話 / 湖南 话 ) | approx. 38 million | China: Hunan |

The North Chinese dialects ( 北方 話 / 北方 话 , Běifānghuà , 北方 方言 , Běifāng Fāngyán ), technically also called Mandarin ( 官 話 / 官 话 , Guānhuà ), are by far the largest dialect group; it includes the entire Chinese-speaking area north of the Yangzi and in the provinces of Guizhou , Yunnan , Hunan and Guangxi also areas south of the Yangzi. The dialect of Beijing, the basis of standard Chinese, is one of the Mandarin dialects. The Wu is spoken by about 80 million speakers south of the mouth of the Yangzi, the Shanghai dialect occupies an important position here. To the southwest, the Gan is bordered by the Jiangxi Province with 21 million speakers, and to the west of it, in Hunan, by the Xiang with 36 million speakers. On the coast, in the province of Fujian , in the east of Guangdong as well as on Taiwan and Hainan as well as in Singapore, the Min dialects are spoken, to which a total of around 60 million speakers belong. In Guangxi, Guangdong and Hong Kong , around 70 million people speak the Yue, whose most important dialect is Cantonese, with the centers in Guangzhou and Hong Kong.

The usual classification is primarily phonologically motivated, the most important criterion is the development of originally voiced consonants . But there are also clear lexical differences. The third person pronoun 他 tā (the corresponding high Chinese form), the attribute particles 的 de and the negation 不 bù are typical features of northern dialects, especially Mandarin, but also some of the southern Xiang, Gan and Wu dialects of the lower yangzi, which are influenced by Mandarin. Typical features, especially of southern dialects, on the other hand, are the exclusive use of negations with a nasal initial sound ( e.g. Cantonese 唔 m 21 ), cognata from Old Chinese 渠 qú (Cantonese 佢 kʰɵy˩˧ ) or 伊 yī (Shanghaiian ɦi˩˧ ) as pronouns of the third person as well as some words that are not found in northern dialects or in Old or Middle Chinese, such as “cockroach”, Xiamen ka˥˥-tsuaʔ˥˥ , Cantonese 曱 甴 kaːt˧˧-tsaːt˧˧ , Hakka tshat˦˦ and “poison” “, Fuzhou thau1˧ , Yue tou˧˧ , Kejia theu˦˨ .

The following comparison of etymologically related words from representatives of the large dialect groups shows the genetic togetherness, but also the degree of diversity of the Chinese languages:

| meaning | character | Old Chinese | Standard Chinese | Wu Shanghai |

Yue Guangzhou |

Kejia Meixian |

Min Xiamen |

Xiang Changsha |

Gan Nanchang |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eat | 食 | * Ljɨk | shí | zəʔ˩˨ | sec˨ | st˥ | sit˦ / tsiaʔ˦ | ||

| big | 大 | * lats | there | you | da: i˨˨ | tʰai˥˧ | tai˨˨ / tua˨˨ | ta˥ | tʰai˩ |

| to have | 有 | * wjɨʔ | yǒu | iu˦ | jɐu˨˧ | u˨˨ | iəu˧˩ / u˦˦ | iu˨˧ | |

| die, death | 死 | * sjijʔ | sǐ | ɕi˧˧ | sɛ: i˧˥ | si˧˩ | su˥˧ / si˥˧ | sɿ˧˩ | sɿ˨˧ |

| White | 白 | * brak | bái | bʌʔ˩˨ | bak˨ | pʰak˥ | pik˦ / peʔ˦ | pə˨˦ | pʰaʔ˨ |

| knowledge | 知 | * trje | zhī | tsɿ˧˨ | tsi: ˥˥ | tsai˦˦ | ti˦˦ / tsai˦˦ | ||

| one | 一 | * ʔjit | yī | iɪʔ˥˥ | jɐt˥ | it˩ | it˦ / tsit˦ | i˨˦ | it˥ |

| three | 三 | * sum | sān | sᴇ˥˧ | sam˥˥ | sam˦ | sam˦˦ / sã˦˦ | san˧ | san˧˨ |

| five | 五 | * ngaʔ | wǔ | ɦŋ˨˧ | ŋ˨˧ | ŋ˧˩ | ŋɔ˥˧ / gɔ˨˨ | u˧˩ | ŋ˨˩˧ |

| woman | 女 | * nrjaʔ | nǚ | ȵy˨˨ | noe: i˨˧ | n˧˩ | lu˥˧ | ȵy˧˩ | ȵy˨˩˧ |

| guest | 客 | * khrak | kè | kʰʌʔ˥˥ | hak˧ | hak˩ | kʰik˧˨ / kʰeʔ˧˨ | kʰ ə˨˦ | kʰiɛt˥ |

| hand | 手 | * hjuʔ | shǒu | sɣ˧˧ | sweet | su˧˩ | siu˥˧ / tsʰiu˥˧ | ʂ əu˧˩ | sweet |

| heart | 心 | * sjɨm | xīn | ɕin˧˧ | sɐm˥˥ | sim˦ | sim˦˦ | sin˧ | ɕ˧˨ |

| year | 年 | * nin | nián | ȵi˨˨ | ni: n˨˩ | ŋian˩ | lian˨˦ / ni˨˦ | ȵiɛn˧˥ | |

| king | 王 | * wyang | wáng | uan˩˧ | wɔŋ˨˩ | uɔŋ˦˥ | ɔŋ˨˦ | ||

| human | 人 | * njin | rén | ȵin˨˨ | jɐn˨˩ | ŋip˥ | lin˨˦ / laŋ˨˦ | ȥ ən˩˧ | lɨn˧˥ |

| center | 中 | * k-ljung | zhōng | tsoŋ˥˧ | tsoŋ˥˥ | to do | tiɔŋ˦˦ | tʂɔŋ˧ | tsuŋ˧˨ |

| Name, description | 名 | * mryang | míng | min˨˨ | meŋ˨˩ | mia˨˦ | biŋ˧˥ / mia˧˥ | ||

| ear | 耳 | * njɨʔ | he | ȵei˨˨ | ji: ˨˧ | ŋi˧˩ | ni˥˧ / hi˨˨ | ə˧˩ | e˨˩˧ |

| rain | 雨 | * w (r) yesʔ | yǔ | ɦy˨˨ | jy: ˨˧ | i˧˩ | u˥˧ / hɔ˨˨ | y˧˩ | y˨˩˧ |

| son | 子 | * tsjɨʔ | zǐ | tsɿ˧˧ | tsi: ˧˥ | tsɿ˧˩ | tsu˥˧ / tsi˥˧ | tsɿ˧˩ | tsɿ˨˩˧ |

| Day, sun | 日 | * njit | rì | ȵiɪʔ˥˥ | jɐt˨ | ŋit˩ | lit˦ | ȥʅ˨˦ | lɨt˥ |

| south | 南 | * nɨm | nán | no˨˨ | nam˨˩ | nam˩ | lam˨˦ | lan˩˧ | lan˧˥ |

| Door, gate | 門 / 门 | * mɨn | men | mən˨˨ | mu: n˨˩ | mŋ˨˦ | bən˩˧ / məŋ˩˧ | mɨn˧˥ | |

| people | 民 | * mjin | min | min˨˨ | mɐn˨˩ | min˩ | bin˨˦ |

About the designation

In Chinese itself, a number of different terms are used for the Chinese language. Zhōngwén ( 中文 ) is a general term for the Chinese language that is primarily used for the written language. Since the written language is more or less independent of the dialect, this term also includes most Chinese dialects. Hànyǔ ( 漢語 / 汉语 ), on the other hand, is used primarily for the spoken language, for example in the sentence “I speak Chinese”. Since the word hàn 漢 / 汉 stands for the Han nationality , the term originally includes all dialects spoken by Han Chinese. Colloquially, however, Hànyǔ denotes standard Chinese, for which there is a separate technical term, the Pǔtōnghuà ( 普通話 / 普通话 ). Huáyǔ ( 華語 / 华语 ), on the other hand, is mostly used as a term by Chinese overseas in the diaspora outside of China. The sign huá 華 / 华 is derived from the historical term Huáxià ( 華夏 / 华夏 ) for ancient China. While the designation Tángwén ( 唐文 ) or Tánghuà ( 唐 話 / 唐 话 ) for the Chinese language is derived from the word táng 唐 , the ancient China of the Tang Dynasty .

Relationships with other languages

This section gives a brief overview of the genetic relationship between Chinese and other languages. This topic is dealt with in detail in the article Sino-Tibetan languages .

Genetic Relationship

Tibeto-Burmese

Chinese is now widely regarded as the primary branch of the Sino- Tibetan language family , which comprises around 350 languages with 1.3 billion speakers in China , the Himalayas and Southeast Asia . Most of the classifications of Sino- Tibetan contrast Chinese with the rest of the Tibetan- Burmese language family ; a few researchers consider Sinitic as a sub-unit of Tibetan-Burmese, on a par with the many other sub-groups of this unit.

Chinese has countless lexemes of its basic vocabulary in common with other Sino- Tibetan languages:

| meaning | Chinese |

Classic Tibetan |

Burma cally |

Lahu | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| character | High- | Old- | ||||

| "I" | 我 | wǒ | * ngajʔ | nga | nga | ngà |

| "three" | 三 | sān | * sum | gsum | sûm | |

| "five" | 五 | wǔ | * ngaʔ | lnga | ngâ | ngâ |

| "six" | 六 | liù | * Crjuk | drug | khrok | hɔ̀ʔ |

| "nine" | 九 | jiǔ | * kuʔ | dgu | kûi | qɔ̂ |

| "Sun / day" | 日 | rì | * njit | nyima | no | ní |

| "Surname" | 名 | míng | * mjeng | ming | mañ | mɛ |

| "bitter" | 苦 | kǔ | * khaʔ | kha | khâ | qhâ |

| "cool" | 涼 / 凉 | liáng | * gryang | grang | krak | gɔ̀ |

| "to die" | 死 | sǐ | * sjijʔ | shiba | se | ʃɨ |

| "poison" | 毒 | you | * duk | dug | dew | tɔ̀ʔ |

In addition to the common basic vocabulary, Sinitic and Tibeto-Burmese combine the originally same syllable structure (as it is largely preserved in Classical Tibetan and can be reconstructed for Old Chinese) and a widespread derivative morphology , which is expressed in common consonantic prefixes and suffixes with a meaning-changing function. The Proto-Sino-Tibetan as well as the modern Sinitic languages have not developed a relational morphology (change of nouns and verbs in the sense of a flexion); this form of morphology is an innovation of many Tibetan-Burmese language groups, which is achieved through cross-regional contacts with neighboring languages and overlaying older substrate languages originated.

Other languages

The genetic relationship between Chinese and languages outside of Tibeto-Burmese is not generally recognized by linguistics, but there have been some attempts to classify Chinese into macro-families that go far beyond the traditional language families. For example, some researchers represent a genetic relationship with the Austronesian languages , the Yenisese languages or even the Caucasian or Indo-European languages , for which word equations such as Chinese 誰 / 谁 , shuí <* kwjəl "who" = Latin quis "who" are used. However, none of these attempts has so far won the approval of a majority of linguists.

Feudal relationships

Due to coexistence with other, genetically unrelated languages for thousands of years, Chinese and various Southeast and East Asian languages have greatly influenced each other. They contain hundreds of Chinese loan words, often names of Chinese cultural assets: chines / 册 , cè - "book"> Korean čhäk , Bai ts h ua˧˧ . These influences have had a particularly strong impact on Korea, Vietnam and Japan, where the Chinese script is also used and classical Chinese has been used as a written language for centuries.

Chinese itself also shows a large number of foreign influences. Some of the main typological features of modern Chinese can probably be traced back to external influences, including the development of a tonal system, the abandonment of inherited morphological means of formation and the obligatory use of counting words. External influence is also evident in the inclusion of no fewer loanwords . The word 虎 , hǔ - “tiger” (old Chinese * xlaʔ) must have been borrowed from the Austro-Asian languages very early on , cf. Mon klaʔ, Mundari kula . The word 狗 , gǒu - "dog", which replaced the older 犬 , quǎn - "dog" during the Han dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) , was probably used during the time of the Zhou dynasty ( around 1100–249 BC) borrowed from the Miao-Yao . In prehistoric times, words were also adopted from neighboring languages in the north, for example 犢 / 犊 , dú - “calf”, which is found in Altaic languages: Mongolian tuɣul , Manchurian tukšan . The number of loan words in Chinese became particularly large during the Han dynasty, when words were also adopted from neighboring western and northwestern languages, for example 葡萄 , pútao - "grapes" from an Iranian language, cf. Persian باده bāda . Borrowings from the Xiongnu language are difficult to prove ; here is presumably 駱駝 / 骆驼 , luòtuo - "camel" to be classified. Due to the strong influence of Buddhism during the 1st millennium AD, a large number of Indian loanwords penetrated Chinese: 旃檀 , zhāntán - "sandalwood" from the Sanskrit candana , 沙門 / 沙门 , shāmén - "Buddhist monk" from the Sanskrit śramaṇa . The Mongolian rule of the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) left only a few loan words , for example 蘑菇 , mógū - "mushroom" from Mongolian moku .

In the 16th century, a strong European influence set in, which was also reflected in the Chinese vocabulary. During this time, Christian terms were borrowed from Chinese: 彌撒 / 弥撒 , mísa - “mass” from the late Latin missa . Since the 19th century, names for the achievements of European technology have also been adopted, although Chinese has proven to be much more resistant to borrowing than Japanese, for example. Examples are: 馬達 / 马达 , mǎdá from the English motor , 幽默 , yōumò from the English humor . In some cases, loanwords found their way into standard Chinese through dialects: e.g. B. 沙發 / 沙发 , shāfā from the Shanghai safa from the English sofa .

A special feature is a group of loan words, especially from Japan, from which not the pronunciation but the spelling is borrowed. This is made possible by the fact that the borrowed word is written in the original language itself with Chinese characters. Western medical terms, which were naturalized in Japan with Chinese characters, also reached China via this route:

- Japanese 革命 kakumei > Standard Chinese 革命 , gémìng - "revolution"

- Japanese 場合 baai > Standard Chinese 場合 / 场合 , chǎnghé - " state of affairs , circumstances"

Writing and socio-cultural status

Traditional script

Chinese has been written with the Chinese script since the earliest known written documents from the 2nd millennium BC . In the Chinese script - apart from a few exceptions - each morpheme is represented with its own character. Since the Chinese morphemes are monosyllabic, each character can be assigned a monosyllabic sound value. Contrary to a common misconception, synonymous but not homophonic words are written with different characters. Both the historically older character quǎn 犬 and the historically younger character gǒu 狗 mean “dog”, but are written with completely different characters. Some characters go back to pictographic representations of the corresponding word, other purely semantically based types also occur.

About 85% of today's characters contain phonological information and are composed of two components, one of which indicates the meaning and the other represents a morpheme with a similar pronunciation. The sign 媽 / 妈 , mā - “mother” consists of 女 , nǚ - “woman” “woman” as a meaning component ( radical ) and 馬 / 马 , mǎ - “horse” as a pronunciation component.

In some cases, one sign represents multiple morphemes, especially etymologically related ones. The number of all Chinese characters is relatively high due to the morphemic principle; the Shuowen Jiezi ( 說文解字 / 说文解字 , Shuōwén Jiězì ) from 100 AD already has almost 10,000 characters; the Yitizi Zidian ( 異體 字 字典 / 异体 字 字典 , Yìtǐzì Zìdiǎn ) from 2004 contains 106,230 characters, many of which are no longer in use or only represent rare spelling variants of other characters. The average number of characters that a Chinese with a university degree can master is less than 5000; around 2000 is considered necessary to read a Chinese newspaper.

The Chinese script is not uniform. Since the writing reform of 1958 are in the People's Republic of China (and later in Singapore ) officially the simplified characters ( abbreviations , 简体字 , jiǎntǐzì ) used in Taiwan , Hong Kong and Macau , however, the so-called "traditional character" will continue to A ( traditional characters , 繁體字 , fántǐzì or 正 體 字 , zhèngtǐzì ). The Chinese writing reform was also not applied to the writing of other languages that use Chinese characters, such as Japanese; In Japan, however, independently simplified character forms, also called Shinjitai , were introduced as early as 1946 .

In addition to the Chinese script, several other scripts were also in use in China. This includes in particular the Nüshu , a women's script used in the province of Hunan since the 15th century . Under the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) the phonetically based Phagspa script was also used for Chinese.

- annotation

Transcriptions

In addition to the Chinese script, there are numerous transcription systems based on the Latin alphabet for standard Chinese and the individual dialects or languages. In the People's Republic of China, Hanyu Pinyin (short: Pinyin) is used as the official Romanization for standard Chinese; Another transcription system that was very widespread, especially before the introduction of pinyin, is the Wade-Giles system. There are no generally recognized transcription systems for the various dialects or languages. It is therefore a bit confusing for people who are not familiar with Chinese if there are historically several Latinized (Romanized) spellings for a Chinese term or name. For example, the spelling of the name Mao Zedong (today officially after Pinyin ) or Mao Tse-tung (historically after WG ), the terms Dao (Pinyin) Tao (WG), Taijiquan (Pinyin) or Tai Chi Chuan (WG) or Gong fu (Pinyin) or Kung Fu (WG), rarely also Gung Fu (unofficial Cantonese transcription ). Earlier forms of Chinese are usually transcribed into pinyin like standard Chinese, although this does not adequately reflect the phonology of earlier forms of Chinese.

Muslim Chinese have also written their language in the Arabic-based script Xiao'erjing . Some who emigrated to Central Asia switched to the Cyrillic script in the 20th century , see Dungan language .

Socio-cultural and official status

Originally, the spoken and written language in China did not differ significantly from one another; the written language followed the developments of the spoken language. Since the Qin dynasty (221–207 BC), however, texts from the late period of the Zhou dynasty became authoritative for the written language, so that classical Chinese as a written language became independent of the spoken language and, in written form, became a general medium of communication across dialect boundaries made out. Classical Chinese, however, served exclusively as the written language of a small elite; the dialect of the capital was used as the spoken language by the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) even by the high-ranking officials. When reading texts in Classical Chinese, the respective local dialect was used, some dialects had their own phonological subsystems that differed from the spoken language.

Especially in connection with the spread of Buddhism in China, popular literature was increasingly written in the vernacular Baihua ( 白話 / 白话 , báihuà ), which was standardized to a certain extent in writing within China and, with a few exceptions, such as the Lijingji written in southern Min from the 16th century, based on early forms of the Mandarin dialects. It is possible that there was also a standardization in the spoken language of the 1st millennium AD.

It was not until the end of the Chinese Empire, at the beginning of the 20th century, that the importance of classical Chinese waned; As an official language and as a literary language, it was replaced by standard Chinese by the middle of the 20th century , which is heavily based on the modern dialect of Beijing in terms of grammar, lexicon and especially phonology. Attempts have also been made to translate other dialect forms of Chinese into writing, but only Cantonese has an established Chinese script. In some dialects, attempts have been made to write them down using the Latin script.

Even outside the written language, standard Chinese is increasingly displacing local idioms, as standard Chinese is taught in schools across the country, although it probably only replaces the dialects as colloquial languages in places.

Homophony and homonymy

Since the Chinese script includes over 10,000 different logograms , while the spoken standard Chinese has fewer than 1,700 different spoken syllables, Chinese has significantly more homophonic morphemes, i.e. word components with different meanings and the same pronunciation, than any European language. Therefore, neither spoken language nor Roman transcriptions exactly match the texts written in Chinese characters. Simplified transcriptions that do not mark the tones make the homophony appear even more pronounced than it actually is.

There are also homonyms in Chinese, i.e. different terms that are referred to with the same word. Despite the many different logograms, there are also some homographs , i.e. words that are written with the same characters. Although most Chinese homographs are pronounced the same, there are some with different pronunciations.

Periodization

Chinese is one of the few languages still spoken with a written tradition going back more than three thousand years. Language development can be divided into several phases from a syntactic and phonological point of view.

The oldest form of Chinese that can be recorded by written records is the language of oracle bone inscriptions from the late Shang dynasty (16th – 11th centuries BC). They form the forerunner of the language of the Zhou dynasty (11th – 3rd centuries BC), which is known as Old Chinese ( 上古 漢語 / 上古 汉语 , Shànggǔ Hànyǔ ) and its late form as Classical Chinese until modern times as a written language was preserved.

After the Zhou dynasty, the spoken language gradually moved away from classical Chinese; first grammatical innovations can be found as early as the 2nd century BC. They denote the Middle Chinese ( 中古 漢語 / 中古 汉语 , Zhōnggǔ Hànyǔ ), which mainly influenced the language of popular literature.

The period since the 15th century includes modern Chinese ( 現代漢語 / 现代 汉语 , Xiàndài Hànyǔ ) and contemporary Chinese ( 近代 漢語 / 近代 汉语 , Jìndài Hànyǔ ), which serves as the umbrella term for the modern Chinese languages.

Typology

In typological terms, modern Chinese shows relatively few similarities with the genetically related Tibeto-Burmese languages, while it shows considerably more similarities with the Southeast Asian languages that have been directly neighboring for centuries. In particular, modern Chinese is very isolating and shows little inflection ; the syntactic connections are therefore predominantly expressed by the sentence order and free particles. However, modern Chinese also knows morphological processes for word and form formation.

Phonology

Segments

The phoneme inventory of the various Chinese languages is very diverse; however, some features have become widespread; for example the presence of aspirated plosives and affricates and, in a large part of the dialects, the loss of voiced consonants. The Min dialects in the south of China are very atypical from a historical point of view because they are very conservative, but from a typological point of view they give a good cross-section of the consonant inventory of Chinese, which is why the following is the consonant system of the Min dialect of Fuzhou ( Min Dong ) is shown:

| bilabial | alveolar | palatal | velar | glottal | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | |

| Plosives | p | pʰ | t | tʰ | k | kʰ | ʔ | ||||||||

| Fricatives | s | H | |||||||||||||

| Affricates | ts | tsʰ | |||||||||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||||||||||||

| Approximants and Lateral | w | l | j | ||||||||||||

These consonants can be found in almost all modern Chinese languages; most have various additional phonemes. For example, in Yue Labiovelare there is a palatal nasal (ɲ) in some dialects and in Mandarin and Wu there are palatal fricatives and affricates. The standard Chinese has the following consonant phonemes (the Pinyin transcription in brackets):

| bilabial |

labio- dental |

dental / alveolar |

retroflex | palatal | velar | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | stl. | sth. | asp. | |

| Plosives | p (b) | pʰ (p) | t (d) | tʰ (t) | k (g) | kʰ (k) | ||||||||||||

| Affricates | ts (z) | tsʰ (c) | tʂ (zh) | tʂʰ (ch) | tɕ (j) | tɕʰ (q) | ||||||||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ (ng) | |||||||||||||||

| Fricatives | f | s | ʂ (sh) | ɕ (x) | x (h) | |||||||||||||

| Approximants | w | ɹ̺ (r) | j (y) | |||||||||||||||

| Lateral | l | |||||||||||||||||

Syllable structure

Traditionally, the Chinese syllable is divided into a consonant initial ( 聲母 / 声母 , shēngmǔ ) and an end ( 韻母 / 韵母 , yùnmǔ ). The final vowel consists of a vowel, which can also be a di or triphthong , and an optional final consonant ( 韻 尾 / 韵 尾 , yùnwěi ). The syllable xiang can be broken down into the initial x and the final iang , which in turn is analyzed into the diphthong ia and the final consonant ng . In all modern Chinese languages, the initial sound - apart from affricates - always consists of a single consonant (or ∅); it is assumed, however, that ancient Chinese also had clusters of consonants in the initial sound. The modern Chinese languages only allow a few final consonants; in standard Chinese, for example, only n and ŋ ; here too, however, the freedom in ancient Chinese was probably much greater. Because of these very limited possibilities for syllable formation, homonymy is very pronounced in modern Chinese.

tonality

Probably the most obvious feature of Chinese phonology is that the Chinese languages - like many neighboring genetically unrelated languages - are tonal languages . The number of tones, mostly contour tones, varies greatly between the different languages. By 800 AD, Chinese had eight tones, but only three oppositions actually had phonemic meanings. In the various modern Chinese languages, the ancient tonal system has changed significantly, standard Chinese, for example, only shows four tones, but all of them are phonemic, as the following examples show (see the article Tones of Standard Chinese ):

| 1st tone | 2nd tone | 3rd tone | 4th tone |

|---|---|---|---|

| consistently high | increasing | falling low - rising | sharply sloping |

| 媽 / 妈 , mā - "mother" | 麻 , má - "hemp" | 馬 / 马 , mǎ - "horse" | 罵 / 骂 , mà - "scold" |

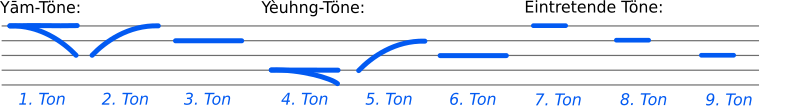

The Cantonese dialect of Yue, on the other hand, has better preserved the ancient system and has nine tones, which are divided into certain categories:

It is generally believed that the Chinese tonal system originated mainly under the influence of eroded consonants at the end of the syllable; In the opinion of the majority of researchers, Old Chinese was therefore not yet a tonal language.

morphology

Word formation

The basis of Chinese morphology is the monosyllabic morpheme , which corresponds to a character in the written form of the language. Examples in standard Chinese are the independent lexemes 大 , dà - “to be large”, 人 , rén - “human”, 去 , qù - “to go” and affixes such as the plural suffix 們 / 们 , men -. Exceptions are groups of two consecutive morphemes that form a single syllable. In some cases, this is due to phonological changes when two morphemes come together (so-called sandhi ), such as in standard Chinese 那兒 / 那儿 nà-ér> nàr “there”, classical Chinese 也 乎 yě-hū> 與 / 与 , yú , Cantonese 嘅 呀kɛː˧˧ aː˧˧> 嘎 kaː˥˥. Since the affixes of the ancient Chinese word formation morphology did not form their own syllable, the derivatives discussed below also belong to these exceptions. It has not yet been clarified whether Old Chinese also had polysyllabic morphemes that were only written with one character.

In Old Chinese, the morpheme boundaries corresponded to the word boundaries in the vast majority of cases. Since the time of the Han Dynasty, new, two-syllable, and bimorphemic lexemes have been formed by composing monosyllabic words. Many such compositions have syntactic structures that are also found in phrases and sentences, which is why the separation of syntax and morphology is problematic. As many nouns as noun phrases formed with an attribute and the following core: 德國人 / 德国人 , déguórén literally: "Germany - Man" = "German" 記者 / 记者 , Jizhe literally, "one who records" = "journalist" . Verbs can also be formed by combining a verb with an object: 吃飯 / 吃饭 , chīfàn - "to have a meal" from 吃 , chī - "to eat" and 飯 / 饭 , fàn - "meal, cooked rice". Other compositions are more difficult to analyze, for example 朋友 , péngyou - "friend" from 朋 , péng - "friend" and the synonym 友 , yǒu .

Affixes are another educational tool for the derivation of words in both ancient and modern Chinese . Ancient Chinese had a large number of prefixes, inscriptions and suffixes, which, however, are often difficult to identify as they leave no or only insufficient traces in the script. A suffix * -s is particularly common, with which both nouns and verbs could be formed ( 知 , zhī (* trje) "to know"> 知 / 智 zhì (* trjes) "wisdom"; 王 , wáng (* wjang ) "King"> 王 , wàng (* wjangs) "rule"). Various infixes and prefixes can also be reconstructed.

Modern Chinese also has a few suffixes for derivation (examples from standard Chinese):

- The plural suffix 們 / 们 –men primarily in the formation of personal pronouns: 我們 / 我们 warm “we”, 你們 / 你们 take “her”, 他們 / 他们 tāmen “she”

- Nominal suffixes:

- - " 子 " -zi in 孩子 , háizi - "child", 桌子 , zhuōzi - "table"

- - " 頭 / 头 " -tou in 石頭 / 石头 , shítou - "stone", 指頭 / 指头 , zhǐtou - "finger, fingertip"

- - " 家 " -jia in 科學家 / 科学家 , kēxuéjiā - "scientist", 藝術家 / 艺术家 , yìshùjiā - "artist"

In various Chinese dialects there are also prefixes , such as the prefix ʔa˧˧- used in the Hakka to form relatives: ʔa˧˧ kɔ˧˧ "older brother" = standard Chinese 哥哥 , gēge . Derivation or inflection by changing tones plays a rather minor role in modern Chinese, for example in the formation of the perfective aspect in Cantonese: 食 sek˧˥ “ate, has eaten” to 食 sek˨˨ “eat”.

Pronouns

The personal pronouns in different forms of Chinese have the following forms:

| Historical languages | Modern languages | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shang and early Zhou period (approx. 1400-800 BC) |

Classical Chinese (approx. 500-300 BC) |

Nanbeichao Period and Tang Dynasty (approx. 400–900 AD) |

Standard Chinese | Shanghaiish | Moiyen-Hakka | Cantonese | ||

| Singular | 1. | 余 * la (yú), 予 * laʔ (yú), 朕 * lrəmʔ (zhèn) | 我 * ŋˤajʔ (wǒ), 吾 * ŋˤa (wú), 余 * la (yú), 予 * laʔ (yú) | 我 wǒ, 吾 wú | 我 wǒ | 吾 ŋu˩˧ | ŋai̯˩˩ | 我 ŋɔː˩˧ |

| 2. | 汝 or 女 * naʔ (rǔ), 乃 * nˤəʔ (nǎi) | 爾 / 尔 * neʔ (ěr), 汝 or 女 * naʔ (rǔ), 而 * nə (ér), 若 * nak (ruò) | 爾 / 尔 ěr, 汝 or 女 rǔ, 你 nǐ | 你 nǐ | 侬厥 noŋ˩˧ | ŋ˩˩ | 你厥 no | |

| 3. | 厥 * kot (jué), 之 * tə (zhī), 其 * gə (qí) (?) | 之 * tə (zhī), 其 * gə (qí) | 其 qí, 渠 qú; 伊 yī, 之 zhī, 他 tā | 他 , 她 , 它 tā | 伊 ɦi˩˧ | ki˩˩ | 佢 kʰɵy˩˧ | |

| Plural | 1. | 我 * ŋˤajʔ (wǒ) | like singular |

Singular + 等 děng , 曹 cáo , 輩 / 辈 bèi |

我們 / 我们 warm | 阿拉 ɐʔ˧˧ lɐʔ˦˦ | ŋai̯˩˩ tɛʊ˧˧ ŋin˩˩ | 我 哋 ŋɔː˩˧ part |

| 2. | 爾 * neʔ (ěr) | 你們 / 你们 name | 㑚 na˩˧ | ŋ˩˩ tɛʊ˧˧ ŋin˩˩ | 你哋 part | |||

| 3. | (not used) | 他們 / 他们 , 她們 / 她们 , 它們 / 它们 tāmen | 伊拉 ɦi˩˩ lɐʔ˧˧ | ki˩˩ tɛʊ˧˧ ŋin˩˩ | 佢 哋 kʰɵy˩˧ tei˨˨ | |||

Early Old Chinese distinguished the numbers singular and plural as well as various syntactic functions in personal pronouns; so served in the 3rd person around 900 BC Chr. 厥 * kot (now jué) as an attribute 之 * tə (now zhī) as an object, and possibly * gə (now qí) as a subject. In Classical Chinese, the distinction between numbers was abandoned, and the syntactic distinction disappeared since the Han period. For this purpose, new plurals have developed since the Tang dynasty, which were now formed by affixes such as 等 děng, 曹 cáo, 輩 / 辈 bèi. This system has remained unchanged in its basic features and can be found in the modern Chinese languages.

syntax

General

Since the Chinese languages are largely isolating , the relationships between the words are primarily expressed through the comparatively fixed sentence order. There is no congruence ; Apart from the personal pronouns of Old and Middle Chinese, no cases are marked. In all historical and modern forms of Chinese the position subject - verb - object (SVO) is predominant, only that pro-drop occurs with subjects :

| 余 | 其 | 作 | 邑 |

| yú | qí | zuò | yì |

| I (nom./acc.) | (Modal particle) | to build | settlement |

| subject | Adverbials | predicate | object |

| "I will build a settlement" | |||

| 他 | 弟弟 | 明天 | 去 | 北京 |

| Tā | dìdi | míngtiān | qù | Běijīng |

| he is) | younger brother | tomorrow | go to) | Beijing |

| subject | Adverbials | predicate | ||

| "His younger brother is going to Beijing tomorrow." | ||||

In certain cases, such as topicalization and in negated sentences, the object can also stand preverbal. The sentence order SOV can be found in various forms of Chinese, especially in negated sentences. In Old Chinese, pronominal objects often preceded negated verbs:

| 未 | 之 | 食 |

| wèi | zhī | shí |

| Not | it | eat |

| Adverbials | object | predicate |

| "(He) did not eat it." | ||

The sentence order SOV has also been possible in other contexts since around the 6th century, if the object is introduced with a particle ( 把 , bǎ , 將 , jiāng and others):

| 他 | 把 | 書 / 书 | 給 / 给 | 張三 / 张三 |

| tā | bǎ | shu | gěi | Zhāngsān |

| he | Particles to identify a preferred object | book | give | Zhangsan |

| "He gives Zhangsan the book" | ||||

In most historical and northern modern variants of Chinese, the indirect object precedes the direct; In some southern languages today, however, the direct precedes:

| Standard Chinese | 我 | 給 / 给 | 你 | 錢 / 钱 |

| wǒ | gěi | nǐ | qián | |

| I | give | you | money | |

| Cantonese | 我 | 畀 | 錢 / 钱 | 你 |

| ŋɔː˨˧ | at˧˥ | tshiːn˧˥ | no˨˧ | |

| I | give | money | you | |

| "I give you money" | ||||

The phenomenon of topicalization plays an important role in Chinese syntax , in which a pragmatically emphasized noun phrase is placed at the beginning of the sentence from its canonical position. In the ancient Chinese were in the extraction of objects and attributes Resumptiva used; these are no longer available in modern Chinese. Topics that stand behind the subject and those that have no direct syntactic reference to the following sentence are also typical of modern Chinese:

| 戎狄 | 是 | 膺 |

| róng dí | shì | yīng |

| Rong and Di | this (sumptive) | resist |

| "The Rong and Di barbarians, he resisted them" | ||

| with extracted object | 中飯 / 中饭 | 她 | 還沒 / 还沒 | 吃 |

| zhōngfàn | tā | hái méi | chī | |

| Having lunch | she | not yet | eat | |

| "She hasn't eaten lunch yet" | ||||

| Topic behind subject | 她 | 中飯 / 中饭 | 吃 | 了 |

| tā | zhōngfàn | chī | le | |

| she | Having lunch | eat | (Aspect particle) | |

| "She had lunch" | ||||

| without syntactic reference | 張三 / 张三 | 頭 / 头 | 疼 | |

| zhāngsān | tóu | téng | ||

| Zhangsan | head | pain | ||

| "Zhangsan, (his) head hurts" | ||||

Interrogativa are in situ in Chinese . Marking questions with interrogatives through final question particles is possible in some ancient and modern variants of Chinese:

| 人 | 從 / 从 | 何 | 生 |

| rén | cóng | hé | shēng |

| human | from | What | arises |

| subject | prepositional adjunct |

predicate | |

| "Where does the person come from?" | |||

| 你 | 去 | 哪兒 / 哪儿 | 啊 |

| nǐ | qù | no | a |

| you | go | Where | (Question particle) |

| "Where are you going?" | |||

Yes-no questions are usually marked with final particles; since the 1st millennium AD there are also questions of the form "A - not - A":

| with particles | 你 | 忙 | 嗎 / 吗 | |

| nǐ | máng | ma? | ||

| you | being busy | (Question particle) | ||

| "A - not - A" | 你 | 忙 | 不 | 忙 |

| nǐ | máng | bù | máng? | |

| you | being busy | Not | being busy | |

| "are you busy?" | ||||

Aspect, tense, type of action and diathesis

Aspect , tense and type of action can be left unmarked or expressed through particles or suffixes, sometimes also through auxiliary verbs . In early Old Chinese, these morphemes were exclusively preverbal; In the later Old Chinese, on the other hand, the most important aspect particles were probably the static - durative yě and the perfective yǐ, which were at the end of the sentence:

| 其 | 雨 |

| qí | yù |

| (Modal particle) | rain |

| "It will (maybe) rain" | |

| 性 | 無 / 无 | 善 | 無 / 无 | 不 | 善 | 也 |

| xìng | wú | shàn | wú | bù | shàn | yě |

| human nature | Not | be good | Not | Not | be good | Aspect Particle |

| "Human nature is neither good nor not good." | ||||||

Since the end of the 1st millennium AD, aspect particles have also been documented that stand between verb and object; this position is widespread in all modern Chinese languages. Also at the end of the sentence and, especially in the Min, in front of the verb, certain aspect particles can still be used. The following table illustrates the constructions that Mandarin Chinese uses to express types of action:

| morpheme | Promotion type | Example sentence | transcription | translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| le | perfect-resultative | 我 當 了 兵 ./ 我 当 了 兵. | wǒ dāng le bīng | "I became a soldier (and still am)" |

| guo | "Experience" -perfective | 我 當 過 兵 ./ 我 当 过 兵. | wǒ dāng guo bīng | "I was (already) a soldier" |

| zhèngzài / zài | dynamic-imperfective (progressive) |

我 正在 掛畫 ./ 我 正在 挂画. | wǒ zhèng zài guà huà | "I'm just hanging up pictures" |

| zhe | static imperfect (durative) |

牆上 掛著 一 幅畫 ./ 墙上 挂着 一 幅画. | qiáng shàng guà zhe yī fú huà | "A picture was on the wall" |

Although all Chinese languages have externally similar systems, the morphemes used show great divergences. The Hakka, for example, uses the preverbal aspect particles ∅ (imperfect), ʔɛ˧˨ (perfect), tɛn˧˨ (continuative), kuɔ˦˥ (“experience-perfect”).

While the active is unmarked in Chinese, there are different options for marking the passive. In Old Chinese it was also originally unmarked and could only be indicated indirectly by specifying the agent in a prepositional phrase. Since the end of the Zhou dynasty, constructions with various auxiliary verbs such as 見 / 见 , jiàn , 為 / 为 , wéi , 被 , bèi , 叫 , jiào and 讓 / 让 , ràng have emerged , but they did not displace the unmarked passive voice .

Verb serialization

An important and productive feature of the syntax of the younger Chinese languages is verb serialization , which has been documented since the early 1st millennium AD. In these structures, two verb phrases that have a certain semantic relation follow each other without any formal separation. In many cases the ratio of the two verb phrases is resultant, so the second gives the result of the first:

| 乃 | 打 | 死 | 之 |

| nǎi | dǎ | sǐ | zhī |

| then | beat | to die | him |

| "Then they beat him to death" | |||

| 他 | 吃 | 完 | 了 |

| tā | chī | wán | le |

| he | eat | be finished | (Aspect particle) |

| "He has finished eating" | |||

Serialized verbs in which the second verb expresses the direction of the action are also common:

| 飛 / 飞 | 來 / 来 | 飛 / 飞 | 出 |

| fēi | lái | fēi | chū |

| to fly | come | to fly | go |

| "They fly in, they fly away" | |||

The so-called Koverben have a similar construction . These are transitive verbs that can not only appear as independent verbs, but can also take over the function of prepositions and modify other verbs:

| as a free verb | 我 | 替 | 你 | |

| wǒ | tì | nǐ | ||

| I | represented | you | ||

| "I represent you" | ||||

| as a coverb | 我 | 替 | 你 | 去 |

| wǒ | tì | nǐ | qù | |

| I | represented | you | go | |

| "I'll go in your place" | ||||

Various serial verb constructions with the morpheme 得 , de or its equivalents in other languages play a special role . In a construction known as the complement of degree , de marks an adjective that modifies a verb. If the verb has an object, the verb is repeated after the object, or the object is topicalized:

| Standard Chinese: transitive, with a repeated verb | 她 | 說 / 说 | 漢語 / 汉语 | 說 / 说 | 得 | 很 | 好 |

| tā | shuō | hànyǔ | shuō | de | hěn | hǎo | |

| she | speak | Chinese | speak | Particles to form the complement | very | be good | |

| "She speaks Chinese very well" | |||||||

| Standard Chinese: transitive, with a topicalized object | 她 | 漢語 / 汉语 | 說 / 说 | 得 | 很 | 好 | |

| tā | hànyǔ | shuō | de | hěn | hǎo | ||

| she | Chinese | speak | Particles to form the complement | very | be good | ||

| "She speaks Chinese very well" | |||||||

| Cantonese (Yue): intransitive | 佢 | 學 / 学 | 得 | 好 | 快 | ||

| kʰɵy˨˧ | hɔk˨˨ | dɐk˧˧ | hou˧˥ | faːi˧˧ | |||

| he | learn | Particles to form the complement | very | fast | |||

| "He learns very quickly" | |||||||

In some dialects such as Cantonese, the object can also be placed after 得 , Jyutping dak 1 .

In addition, 得 , de and the negation 不 , bù or their dialectal equivalents can mark the possibility or impossibility. The particle is followed by a verb indicating the result or direction of the action:

| 這 / 这 | 件 | 事 | 他 | 辦 / 办 | 得 / 不 | 了 |

| zhè | jiàn | shì | tā | bàn | de / bù | liǎo |

| this this this | (Count word) | Thing | he | take care of | Particles to form the complement / not | be finished, |

| "He (cannot) do this thing" | ||||||

Noun phrases

Attributes

In Chinese, the head of a noun phrase is always at the end, pronouns, numeralia and attributes are in front of it and can be separated from this by a particle. This particle has different shapes in different dialects; in Old Chinese, for example , it is 之 , zhī , in standard Chinese 的 , de . The attribute can be its own noun phrase: classical Chinese 誰 之 國 / 谁 之 国 , shuí zhī guó - "whose country" "whose - subordinated particle - country", modern Chinese 這兒 的 人 / 这儿 的 人 , zhè 'r de rén - "the people here" "here - attribute particles - people", Moiyen (Hakka) ŋaɪ̯˩˩- ɪ̯ɛ˥˥ su˧˧ "my book".

If this is expanded by an attribute, complex chains of attributes can arise that can be considered typical of Chinese. Often the attribute is not a noun, but a nominalized verb, optionally with additions such as subject, object and adverbial terms. Such attributes fulfill semantic functions similar to those of relative clauses in European languages. In the following example from standard Chinese, the core of the noun phrase is co- referent with the subject of the nominalized verb:

| 買 / 买 | 書 / 书 | 的 | 人 |

| mǎi | shu | de | rén |

| to buy | book | Attribute particle | People |

| "People who buy books" | |||

The head of the noun phrase can also be co-referent with other additions to the nominalized verb, such as its object. In most dialects this is not formally marked, but some resumptiva can be found:

| kʰiu˦˨-ŋiæn˩˨-ŋi˩˨ | May | ɪɛ˦˨ | su˧˧ |

| last year | to buy | Attribute particle | book |

| "The book that (I) bought last year" | |||

| 我 | 請 / 请 | 佢 哋 | 食飯 / 食饭 | 嘅 | 朋友 |

| ŋɔː˩˧ | tshɛːŋ˧˥ | kʰɵy1˧tei˨˨ | sɪk˨˨-faːn˧˧ | kɛː˧˧ | pʰɐŋ˥˧yɐu˧˥ |

| I | invite | she (resumptive) | eat | (Attribute particle) | Friends |

| "Friends I invite to dinner" | |||||

Note: In everyday life the Cantonese sentence above is seldom formulated in this way.

| (我) | 請 / 请 | 食飯 / 食饭 | 嘅 | 朋友 | |

| ŋɔː˩˧ | tshɛːŋ˧˥ | sɪk˨˨-faːn˧˧ | kɛː˧˧ | pʰɐŋ˥˧yɐu˧˥ | |

| (I) | invite | eat | (Attribute particle) | Friends | |

| "Friends I invite to dinner" | |||||

Note: In everyday life it is also common to leave out the subject (here: I - 我 ) in Cantonese if the context is clear in the conversation.

| 嚟 | 食飯 / 食饭 | 嘅 | 朋友 | ||

| lɛːi˨˩ | sɪk˨˨-faːn˧˧ | kɛː˧˧ | pʰɐŋ˥˧yɐu˧˥ | ||

| come | eat | (Attribute particle) | Friends | ||

| "Friends who come to dinner" | |||||

Old Chinese could use the morphemes 攸 , yōu (pre-classical), 所 , suǒ (classical) in cases where the head is not koreferent with the subject of the verb : 攸 馘 , yōuguó "which was cut off".

Counting words

An essential typological feature that modern Chinese shares with other Southeast Asian languages is the use of counting words . While numbers and demonstrative pronouns can be placed directly in front of nouns in Old Chinese ( 五 人 , wǔ rén - "five people"; 此 人 , cǐ rén - "this person"), in modern Chinese languages there must be a counting word between the two words depends on the noun: Standard Chinese 五 本書 / 五 本书 , wǔ běn shū - "five books", 這個 人 / 这个 人 , zhè ge rén - "this person". In the Yue and Xiang dialects, counting words are also used to determine a noun and to mark an attribute: Cantonese 佢 本書 / 佢 本书 , Jyutping keoi 5 bun 2 syu 1 - “jmds book, whose book” “ kʰɵy˨˧ puːn ˧˥ SY " 支筆 / 支笔 , Jyutping zi 1 asked one -" the pen " ," TSI pɐt˥˥ " . The choice of the counting word is determined by the semantics of the noun: 把 , bǎ stands in standard Chinese for nouns that designate a thing that has a handle; with 所 , suǒ nouns that denote a building are constructed, etc. An overview of important counting words in standard Chinese is provided in the article List of Chinese Counting Words .

Language code according to ISO 639

The ISO standard ISO 639 defines codes for labeling language materials. The Chinese languages are subsumed under the language codes zh(ISO 639-1) and zho/ chi(ISO 639-2 / T and / B) in the standard . The ISO 639-3 standard introduces the language code zhoas a so-called macro language - a construct which is used for a group of languages if this can be treated as a unit. In the case of the Chinese languages, this factor is given by the common written form. The individual languages subsumed are in detail: gan( Gan ), hak( Hakka ), czh( Hui ), cjy( Jin ), cmn( Mandarin including Standard Chinese ), mnp( Min Bei ), cdo( Min Dong ), nan( Min Nan ), czo( Min Zhong ), cpx( Pu-Xian ), wuu( Wu ), hsn( Xiang ), yue( Yue - Cantonese ). Also lzh( classical Chinese ) is one of these macro language, but not dng( Dungan ). The ISO 639-5 standard uses the code to designate the entire language group zhx.

literature

General

- John DeFrancis: The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1984

- Bernhard Karlgren : Writing and language of the Chinese . 2nd edition, Springer, 2001, ISBN 3-540-42138-6 .

- Jerry Norman: Chinese. Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-521-22809-3 , ISBN 0-521-29653-6 .

- S. Robert Ramsey: The Languages of China. 2nd Edition. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1987. ISBN 0-691-06694-9 , ISBN 0-691-01468-X .

- Graham Thurgood and Randy J. LaPolla: The Sino-Tibetan Languages. Routledge, London 2003. (on Chinese: pages 57-166)

Language history and historical languages

- William H. Baxter: A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Trends in Linguistics, Studies and monographs No. 64 Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992. ISBN 3-11-012324-X .

- AWAKE Dobsonian: Early Archaic Chinese. A descriptive grammar. University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1962 (covers the language of the 11th and 10th centuries BC)

- И. С. Гуревич. И. Т. Зограф: Хрестоматия по истории китайского языка III-XV вв. (Chrestomacy for the history of the Chinese language from the 3rd to the 15th centuries) , Moscow 1984

- Robert H. Gassmann, Wolfgang Behr: Antikchinesisch - A textbook in two parts. (= Swiss Asian Studies 19 ). 3rd revised and corrected edition, Peter Lang, Bern 2011, ISBN 978-3-0343-0637-9 .

- Alain Peyraub: Recent issues in chinese historical syntax . In: C.-T. James Huang and Y.-H. Audrey Li: New Horizons in Chinese Linguistics , 161-214. Kluwer, Dordrecht 1996

- Edwin G. Pulleyblank : Outline of a Classical Chinese Grammar (Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press 1995); ISBN 0-7748-0505-6 , ISBN 0-7748-0541-2 .

- Wang Li (王力): 漢語 史稿 (sketch of the history of Chinese) . Beijing 1957.

- Dan Xu: Typological change in Chinese syntax . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2007, ISBN 0-19-929756-8 .

- Yang Bojun (杨伯峻) and He Leshi (何乐士): 古 汉语 语法 及其 发展 (The grammar and development of ancient Chinese) . Yuwen Chubanshe, Beijing 2001

Modern languages

- Chales N. Li and Sandra A. Thompson: Mandarin Chinese. A Functional Reference Grammar. University of California Press, Berkeley 2003

- Huang Borong (黄伯荣) (Ed.): 汉语 方言 语法 类 编 (Compendium of the grammar of Chinese dialects) . Qingdao Chubanshe, Qingdao 1996, ISBN 7-5436-1449-9 .

- Mataro J. Hashimoto: The Hakka Dialect. A linguistic study of Its Phonology, Syntax and Lexicon. University Press, Cambridge 1973, ISBN 0-521-20037-7 .

- Nicholas Bodman: Spoken Amoy Hokkien. 2 volumes, Charles Grenier, Kuala Lumpur 1955–1958 (covers the southern min)

- Ping Chen: Modern Chinese. History and Sociolinguistics . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1999

- Stephen Matthews and Virginia Yip: Cantonese. A Comprehensive Grammar. Routledge, London / New York 1994

- Yinji Wu: A synchronic and diachronic study of the grammar of the Chinese Xiang dialects. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin 2005

- Yuan Jiahua (袁家 骅): 汉语 方言 概要 (an outline of the Chinese dialects) . Wenzi gaige chubanshe, Beijing 1960

- Anne O. Yue-Hashimoto: Comparative Chinese Dialectal Grammar - Handbook for Investigators ( Collection des Cahiers de Linguistique d'Asie Orientale , Volume 1). Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris 1993, ISBN 978-2-910216-00-9 .

- Yuen Ren Chao: A grammar of spoken Chinese . University of California Press, Berkeley 1968 (covers the Mandarin dialect of Beijing)

Lexicons

- Instituts Ricci (ed.): Le Grand Dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise . Desclée de Brouwer, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-220-04667-2 .

- Robert Henry Mathews: Mathews' Chinese-English dictionary. China Inland Mission, Shanghai 1931; Reprints: Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1943 etc.

- Werner Rüdenberg, Hans Otto Heinrich Stange: Chinese-German dictionary. Cram, de Gruyter & Co., Hamburg 1963.

- Li Rong (李荣): 现代 汉语 方言 大 词典 (Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects.) . Jiangsu jiaoyu chubanshe, Nanjing 2002, ISBN 7-5343-5080-8 .

Web links

General

- Link catalog on Chinese at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Ethnologue China including Taiwan

- Sinitic languages in the World Atlas of Language Structures

Dictionaries

- German-Chinese word and phrase dictionary (DeHanCi online dictionary) DeHanCi

- Chinese-German Dictionary HanDeDict

- German-Chinese Dictionary Hablaa

- Chinese etymological database (English)

- William Baxter, Etymological Dictionary of Chinese ( Memento June 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- Reconstruction of the old Chinese pronunciation (William Baxter and Laurent Sagart)

- Chinese-German dictionary with focus on single (long) characters

- Online dictionary with audio, vocabulary trainer etc. on leo.org

- Online dictionary including pronunciation training

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://etnic.ru/etnic/narod/tazy.html

- ↑ http://stat.kg/images/stories/docs/tematika/demo/Gotov.sbornik%202009-2013.pdf

- ↑ https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20070630174639/http://www.ecsocman.edu.ru/images/pubs/2005/06/13/0000213102/010Alekseenko.pdf

- ↑ Allès, Elisabeth. 2005. "The Chinese-speaking Muslims (Dungans) of Central Asia: A Case of Multiple Identities in a Changing Context," Asian Ethnicity 6, No. 2 (June): 121-134.

- ↑ a b c Reconstruction based on: William H. Baxter: A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Trends in Linguistics, Studies and monographs No. 64 Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992, ISBN 3-11-012324-X .

- ^ Forms according to Norman 1988, 213

- ↑ Baxter 1992

- ↑ Xu Baohua et al. a .: Shanghaihua Da Cidian . Shanghai Ceshu Chubanshe, Shanghai 2006

- ^ Oi-kan Yue Hashimoto: Phonology of Cantonese. University Press, Cambridge 1972 and Matthews and Yip 1994

- ↑ a b c Li 2002

- ↑ 周长 楫 (Zhou Changji): 闽南 方言 大 词典 (Great Dictionary of the Southern Min Dialects) . 福建 人民出版社, Fuzhou 2006, ISBN 7-211-03896-9 .

- ↑ after Norman 1987 and James Alan Matisoff: Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman: System and Philosophy of Sino-Tibetan Reconstruction . University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-09843-9

- ↑ C stands for an unknown consonant

- ↑ word equation and reconstruction * kwjəl by Edwin G. Pulleyblank: The historical and prehistorical relationships of Chinese. In: WS-Y. Wang (Ed.): The Ancestry of the Chinese Language . 1995. pp. 145-194

- ^ Reconstruction based on Baxter 1992, who, however, rejects the existence of the * -l-

- ↑ 梅祖麟: 唐代 、 宋代 共同 语 的 语法 和 现代 方言 的 语法. In: Paul Jen-kuei Li, Chu-Ren Huang, Chih-Chen Jane Tang (Eds.): Chinese Languages and Linguistics II: Historical Linguistics. (Symposium Series of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, Number 2) . Taipei 1994, pp. 61-97.

- ↑ according to Norman 1987, p. 236

- ^ Karlgren, Bernhard: Writing and language of the Chinese. 2nd ed., Berlin a. a .: Springer, 2001, p. 20 ff.

- ↑ Matthews and Yip 1994, 26

- ↑ Laurent Sagart: The Roots of Old Chinese. (Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science, Servies IV, Volume 184) John Benjamin, Amsterdam / Philadelphia 1999, ISBN 90-272-3690-9 , pp. 142-147; AWAKE Dobsonian: Early Archaic Chinese. A descriptive grammar. University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1962, pp. 112-114.

- ^ A b William H. Baxter, Laurent Sagart: Old Chinese: a new reconstruction . Oxford University Press, New York City 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5 (English, Chinese, PDF files for download - ancient Chinese reconstructions after Baxter and Sagart).

- ↑ The specified shapes are only a selection.

- ↑ a b c d Hashimoto 1973

- ↑ Jiaguwen Heji 13503

- ↑ a b c d Matthews and Yip 1994

- ↑ Shijing 300

- ↑ Baiyujing (百 喻 經), 0.5; Quoted from Thesaurus Linguae Sericae ( Memento from January 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), In: tls.uni-hd.de, accessed on July 21, 2019

- ↑ Mencius 6A / 6

- ↑ Shi Jing 241

- ↑ 639 Identifier Documentation: zho on iso639-3.sil.org, accessed on August 10, 2018.

- ↑ Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages Part 5: Alpha-3 code for language families and groups at www.loc.gov, accessed September 3, 2018.