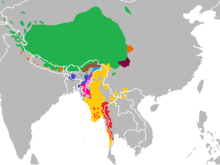

Tibeto-Burmese languages

The Tibetan Burmese languages represent one of the two main branches of the Sino- Tibetan language family , the other branch are the Chinese or Sinitic languages . The approximately 330 Tibetan Burmese languages are spoken by almost 70 million people in southern China, the Himalayan region and Southeast Asia. (In contrast, the Chinese languages together have 1.3 billion speakers.)

By far the most speaker-rich Tibetan- Burmese language is Burmese with around 35 million native speakers and a further 15 million secondary speakers in Burma .

Main languages

The following Tibetan Burmese languages have at least one million speakers:

- Burmese language (Burmese): 35 million speakers; with second speaker 50 million / Myanmar (Burma)

- Tibetan : 6 million; with other Tibetan dialects over 8 million speakers

- Yi (Yipho): 4.2 million / South China

- Sgaw (Sgo): 2 million / Burma: Karen state

- Rakhain (Arakanese): 2 million / Burma: Arakan

- Meithei (Manipuri): 1.3 million / India: Manipur, Assam, Nagaland

- Pwo (Pho): 1.3 million / Burma: Karen state

- Tamang : 1.3 million / Nepal: Kathmandu Valley

- Bai (Minchia): 1.3 million / China: Yunnan

- Yangbye : 1 million / Burma

The article contains a table in the appendix with all Tibetan Burmese languages that have at least 500,000 speakers. The given web link contains all Tibetan Burmese languages with classification and number of speakers.

classification

State of the classification

The internal classification of the 330 or so Tibetan Burman languages can by no means be taken for granted today. Although research has been able to agree on a number of smaller genetic units - including Tibetan , Kiranti , Tani , Bodo-Koch , Karen , Jingpho-Sak , Kuki-Chin and Burmese - the question of medium and larger subgroups that contain these summarize smaller units, so far not resolved by consensus. The reasons are a lack of detailed research, grammars and lexicons for many Tibetan Burmese individual languages, intensive mutual areal influences that obscure the genetic connections, and the large number of languages to be compared.

While Matisoff “dares” to summarize quite large units in 2003, van Driem tends to the other extreme in 2001: he divides Tibetan Burman into many small subgroups and gives only vague information about broader relationships. Thurgood 2003 takes a middle path. The presentation of the present article is based - as far as the intermediate units are concerned - primarily on Thurgood, for the detailed structure on the extensive work van Driem 2001, in which all the Tibetan-Burman languages known by now and their close relationships are dealt with. Overall, there is a relatively small division of Tibetan Burman into genetically secured units.

Internal structure

On the basis of the current research situation cited, the following internal structure of Tibetan Burmese can be justified, even if a complete consensus has not yet been reached on all subunits:

Internal structure of Tibeto-Burmese

-

Tibeto Burmese

- Bodisch with Tibetan, Tamang-Ghale, Tshangla, Takpa, Dhimal-Toto

- West Himalayan

- Mahakiranti with Kiranti, Newari-Thangmi, Magar-Chepang

- North Assam with Tani (Abor-Miri-Dafla), Khowa-Sulung, Mijuisch (Deng), Idu-Digaru

- Hrusian

- Bodo-Konyak-Jingpho with Bodo-Koch (Barisch), Konyak (North Naga), Jingpho-Sak (Kachin-Luisch)

- Kuki-Chin-Naga with Mizo-Kuki-Chin, Ao, Angami-Pochuri, Zeme, Tangkhul, Meithei (Manipuri), Karbi (Mikir)

- Qiang-Gyalrong with Xixia-Qiang and Gyalrong

- Nungisch

- Karen

- Lolo-Burmese with Lolo (Yipho) and Burmese

- Individual languages : Pyu †, Dura †, Koro , Lepcha , Mru , Naxi , Tujia , Bai

Statistical and geographic data

The following table gives a statistical and geographical overview of the subunits of Tibeto Burman. The data are based on the “Classification of Sino-Tibetan Languages” web link given below. The number of languages is significantly lower than in Ethnologue , since Ethnologue - contrary to the majority of research opinion - declares many dialects to be independent languages. The data used here (number of languages, number of speakers) are mainly based on the detailed presentation in van Driem 2001.

The subunits of Tibeto-Burmese

with the number of languages and speakers and their main distribution areas

| Language unit | Alternat. Surname | Number of languages |

Number of speakers |

Main distribution area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIBETO BURMAN | 332 | 68 million | Himalayas, South China, Southeast Asia | |

| Bodisch | Tibetan iwS | 64 | 8 million | Tibet, North India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan |

| Tibetan | 51 | 6 million | Tibet, North India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan | |

| Tamang-Ghale | 9 | 1.2 million | Nepal | |

| Tshangla | 1 | 150 thousand | Bhutan | |

| Takpa | Moinba | 1 | 80 thousand | India: western tip of Arunachal / Tibet |

| Dhimal Toto | 2 | 35 thousand | Nepal: Terai, India: West Bengali | |

| West Himalayan | 14th | 110 thousand | North India: Kumaon, Lahul, Kinnaur; Western Tibet | |

| Mahakiranti | Himalayan | 40 | 2.2 million | Nepal |

| Kiranti | 32 | 500 thousand | Nepal (south of the Mount Everest massif) | |

| Magar-Chepang | 5 | 700 thousand | Central Nepal | |

| Newari thangmi | 3 | 950 thousand | Nepal: Kathmandu Valley / Gorkha District | |

| Lepcha | Rong | 1 | 50 thousand | India: Sikkim, Darjeeling; also Nepal, Bhutan |

| Dura † | 1 | † | Nepal: Lamjung District | |

| North Assam | Brahmaputran | 32 | 850 | India: Arunachal Pradesh, Assam; Bhutan |

| Tani | Abor-Miri-Dafla | 24 | 800 thousand | India: Central Arunachal Pradesh |

| Khowa Sulung | Kho-Bwa | 4th | 10 thousand | India: West. Arunachal Pradesh |

| Idu-Digaru | North Mishmi | 2 | 30 thousand | India: Arunachal Pradesh (Lohit District) |

| Mijuish | South Mishmi | 2 | 5 thousand | India: Arunachal Pradesh (Lohit District) |

| Hrusian | 3 | 7 thousand | Border area India (Arunachal Pradesh) - Bhutan | |

| Bodo-Konyak-Jingpho | 27 | 3.4 million | Northeast India, Nepal, Burma, South China | |

| Bodo cook | Barely | 11 | 2.3 million | Northeast India: Assam |

| Konyak | North Naga | 7th | 300 thousand | India: Arunachal Pradesh; Nagaland |

| Jingpho-Sak | Kachin-Luisch | 9 | 800 thousand | Bangladesh, Northeast India, North Burma, South China |

| Kuki-Chin-Naga | 71 | 5.2 million | Northeast India: Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, Arunachal | |

| Mizo-Kuki-Chin | 41 | 2.3 million | Northeast India, Bangladesh, Burma | |

| Ao | 9 | 300 thousand | Northeast India: Nagaland | |

| Angami-Pochuri | 9 | 430 thousand | Northeast India: Nagaland | |

| Zeme | 7th | 150 thousand | Northeast India: Nagaland, Manipur | |

| Thangkul | 3 | 150 thousand | Northeast India: Nagaland, Manipur | |

| Meithei | Manipuri | 1 | 1.3 million | Northeast India: Manipur, Nagaland, Assam |

| Karbi | Mikir | 1 | 500 thousand | Northeast India: Assam, Arunachal Pradesh |

| Qiang Gyalrong | 15th | 500 thousand | South China: Sichuan | |

| Tangut-Qiang | Xixia-Qiang | 10 | 250 thousand | South China: Sichuan |

| Gyalrong | rGyalrong | 5 | 250 thousand | South China: Sichuan |

| Nungisch | Dulong | 4th | 150 thousand | South China, North Burma |

| Tujia | 1 | 200 thousand | South China: Hunan, Hubei, Guizhou | |

| Bai | Minchia | 1 | 900 thousand | South China: Yunnan |

| Naxi | Moso | 1 | 280 thousand | South China: Yunnan, Sichuan |

| Karen | 15th | 4.5 million | Burma, Thailand | |

| Lolo-Burmese | 40 | 43 million | Burma, Laos, South China, Vietnam | |

| Lolo | Yipho | 27 | 7 million | South China, Burma, Laos, Vietnam |

| Burmese | 13 | 36 million | Burma, South China | |

| Mru | 1 | 40 thousand | Bangladesh: Chittagong; Burma: Arakan | |

| Pyu † | 1 | † | formerly Northern Burma |

The primary branches of Tibetan Burmese are printed in bold, followed by the subunits.

The article Sino- Tibetan Languages contains a detailed discussion of the validity of the subunits of Tibeto-Burmese presented here and other research-proposed subunits.

Linguistic characteristics of Tibeto-Burmese

Tibetan Burman forms a genetic unit within Sino-Tibetan. The Tibetan Burman proto-forms could be reconstructed to a large extent (Matisoff 2003). The common lexical material is extremely extensive and becomes increasingly reliable as the research of other languages increases (see the table of word equations). In addition to the lexical material, there are enough phonological and grammatical similarities that ensure the genetic unity of Tibeto-Burmese.

Syllable structure and phonemes

Proto-Tibeto Burmese was - like Proto-Sino-Tibetan - a monosyllabic language throughout. Its syllable structure can be described as

- (K) - (K) -K (G) V (K) - (s) (K consonant, V vowel, G glide / l, r, j, w /)

reconstruct (potential slots are indicated by (.)). The first two consonants are originally meaning-relevant "prefixes", the actual root has the form K (G) V (K), the final consonant must be from the group / p, t, k, s, m, n, ŋ, l, r , w, j / originate, vowel final is rare. The vowel can be short or long, the length is phonemic. A weak vowel / ə / can be used between the prefix consonants and the initial consonant (a so-called Schwa ). This original syllable structure is documented in classical Tibetan and some modern western Tibetan languages and in the Gyalrong (which are therefore particularly important for the reconstruction), but less completely in Jingpho and Mizo. The complex initial clusters have been reduced in many languages. This structural simplification obviously often led to the development of differentiating tones.

According to Benedict 1972 and Matisoff 2003, the consonant inventory of Proto-Tibeto Burmese - which was used in full for the initial consonants of the root - consisted of the following phonemes:

- p, t, k; b, d, g; ts, dz; s, z, h; m, n, ŋ; l, r, w, j.

As the initial consonant of the word root, these phonemes found the following regular sound equivalents in individual groups:

| Tibetobirm. | Tibet. | Jingpho | Birman. | Garo | Mizo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * p | p (h) | p (h), b | p (h) | p (h), b | p (h) |

| * t | t (h) | t (h), d | t (h) | t (h), d | t (h) |

| * k | k (h) | k (h), g | k (h) | k (h), g | k (h) |

| * b | b | b, p (h) | p | b, p (h) | b |

| * d | d | d, t (h) | t | d, t (h) | d |

| *G | G | g, k (h) | k | g, k (h) | k |

| * ts | ts (h) | ts, dz | ts (h) | s, ts (h) | s |

| * dz | dz | dz, ts | ts | ts (h) | f |

| * s | s | s | s | th | th |

| * e.g. | z | z | s | s | f |

| *H | H | O | H | O | H |

| * m | m | m | m | m | m |

| * n | n | n | n | n | n |

| * ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ |

| * l | l | l | l | r | l |

| * r | r | r | r | r | r |

| * w | O | w | w | w | w |

| * j | j | j | j | ts, ds | z |

The alternative equivalents are usually secondary, aspiration can occur under certain conditions, it is not phonemic. The basis of the above table is Benedict 1972, where suitable word equations are listed for these sound equations .

The Tibetan Burman vowel system has been reconstructed as / a, o, u, i, e /. In proto-language, vowels can appear in the middle and in the end of the syllable, not at the beginning of the syllable. However, vowels other than / a / are very rarely found in the final syllable of the proto-language. Endings ending in / -Vw / and / -Vj / are particularly common.

Derivative morphology

According to the unanimous opinion of research, there was no classical relational morphology (i.e. a systematic morphological change in nouns and verbs with categories such as case, number, tense aspect, person, diathesis, etc.). The relational morphology of nouns and verbs that can be found in Tibetan-Burmese languages today is to be seen as an innovation that can be traced back to the areal influences of neighboring languages or to the effect of substrates. As a result of very different influences, very different morphological types could develop.

However, elements of a derivative morphology for Proto-Tibeto-Burmese can be reconstructed with certainty , the reflexes of which can be demonstrated in many Tibetan-Burmese languages. These are consonantic prefixes and suffixes as well as initial alternations that modify the meaning of verbs, but also of nouns. The existence of common derivative affixes and initial sound alternations with identical or similar semantic effects in almost all groups of Tibetan Burman is a strong indication of its genetic unity.

s prefix

The s-prefix has a causative and denominative function, which is originally based on a more general “directive” meaning. Examples:

- Class Tibetan grib "shadow", sgrib- "shadow, darken" (denominative)

- Class Tibetan gril "roll", sgril- " roll up" (denominative)

- Class Tibetan riŋ- "to be long", sriŋ- "extend" (causative)

- Jingpho lot "be free", slot "release" (causative)

- Jingpho dam "get lost", sɘdam "lead astray" (causative)

- Lepcha nak "to be straight", njak <* snak "to make straight" (causative, metathesis sK> Kj )

In other Tibetan-Burmese languages (e.g. Burmese, Lahu, Lolo languages) the s-prefix was lost, but it caused changes in the initial consonant or tonal differentiations. In the case of weak initial consonants, however, an s-prefix can still be recognizable in these languages, for example

- Burmese ʔip "to sleep", sip "to sleep"

- Burmese waŋ "enter", swaŋ "bring in"

Initial alternation

In almost all Tibetan Burmese languages there are pairs of semantically related words that only differ acoustically in that the initial consonant is voiceless or voiced . The unvoiced variant then usually has a transitive meaning , the voiced one an intransitive meaning. There is the theory that the initial sound change was caused by an original * h-prefix - a non-syllabic, pharyngeal sliding sound - (Pulleyblank 2000).

However, this contrast does not exist in Tibetan. Both intransitive as well as transitive verb roots can have a voiced or an unvoiced initial sound, occasionally there are also old unvoiced-voiced intransitive pairs, e.g. B. both gang and ḥkheng, khengs “get full, s. to fill". The transitive counterpart is either ḥgengs, bkang, dgang, khengs (to gang ) or skong, bskangs, bskang, skongs (to kheng, khengs ).

Examples:

- Bahing kuk "bend", guk "be bent"

- Bodo pheŋ "make straight", beŋ "be straight"

n suffix

The n-suffix (also in the variant / -m /, in Tibetan often also / -d /) has primarily a nominalizing, sometimes also a collectivizing function. Examples:

- Class Tibetan rgyu "s. move ", rgyun " context, series, duration, current "

- Class Tibetan gci "urinate", gcin "urine"

- Class Tibetan rku " stolen ", rkun-ma "thief, theft" (nominalization supported by the ending -ma )

- Class Tibetan nye "near (to be)", gnyen "relative"

- Lepcha zo "essen", azom "Essen" (nominalization supported by initial / a- /)

- Lepcha bu "carry", abun "vehicle"

- Proto- Tibeto Burmese * rmi "person", * rmin "people" (collectivizing)

s suffix

The s-suffix also had several functions in Tibetan, but they are no longer productive

- resultative or past-forming in adjectives and verbs

- eg che , "large are" ches "have grown"

- as collective images (similar to the German Ge in the mountains), especially still preserved in compound words as far back as ancient Tibetan

- eg rnam "unit, part"> rnams as plural morphem , sku "(courtly) body, person" + srung "protect"> skusrungs "(collective of) bodyguards" a special military unit

Further derivation suffixes

In addition to the above, there are other derivation suffixes postulated for Tibetan Burman, e.g. B. / -t /, / -j / and / -k /. For none of these suffixes, however, has yet been given a satisfactory functional description that would be valid in at least some units of Sinotibetic. Reference is made to LaPolla (in Thurgood 2003) and Matisoff 2003 for further details.

Common vocabulary

The following word equations clearly show the genetic relationship of the Tibetan Burman languages. They are based on Peiros-Starostin 1996, Matisoff 2003 and the Starostins internet database given below . The word selection is based on Dolgopolsky's list of “stable etymologies” and some words from the Swadesh list, which largely excludes loanwords and onomatopoeia. Each word equation has representatives from up to five languages or language units: Classical Tibetan, Classical Burmese, Jingpho (Kachin), Mizo (Lushai), Lepcha, Proto-Kiranti (reconstruction of Starostin) and Proto-Tibeto Burmese (Matisoff 2003). The transcription is also done according to Matisoff and the underlying database.

Tibetan Burmese word equations

| meaning | Class Tibet. |

Class Birman. |

Jingpho (Kachin) |

Mizo (Lushai) |

Lepcha | Proto- Kiranti |

Proto- Tibeto- Birman. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tongue | lce | hlja | lei | left | * lja | ||

| eye | mig <dmyig | mjak | mjiʔ | With | mik | * mik | * mik |

| heart | snying | hnac | niŋ | * niŋ | * niŋ | ||

| ear | rna- | close | n / A | kna | njor | * nɘ | *n / A |

| nose | sna | hua | well | hua | * nɘ | * na: r | |

| Foot or similar | rkaŋ | crane | crane | keŋ | kaŋ | * kaŋ | |

| Hand or similar | lay | lak | lak | ljok | * lak | * lak | |

| blood | khrag | swij, swe | sài | thi | (t) vi | *Hi | * s-hjwɘy |

| uncle | akhu | 'uh | gu | 'u | ku | * ku | * khu |

| louse | shig | ciʔ | hrik | * srik | * (s) r (j) ik | ||

| dog | khyi | lhwij | gui | 'ui | * coolɘ | * k w ej | |

| Sun, day | nyi (n) | nij | ʃa-ni | ni | nji | * nɘj | * nɘj |

| stone | rdoba | nluŋ | luŋ | luŋ | * luŋ | * luŋ | |

| flow | chubo, gtsangpo, klung | luaij | lui | lui | * lwij | ||

| House | khyim | 'in the | ʃe-cum | 'in | khjum | * kim | * jim, * jum |

| Surname | ming | miŋ | mjiŋ | hmiŋ | * miŋ | * miŋ | |

| kill | gsod | sat | gɘsat | that | *set | * sat | |

| dead | shi | mhaŋ | maŋ | maŋ | mak | * maŋ | |

| long | ringmo | paŋ | pak | * pak, * paŋ | |||

| short | thung | tauh | ge-dun | tan | *volume | * twan | |

| two | gnyis | ŋi | hni | nji | * ni (k) | * ni (j) | |

| I | nga | n / A | ŋai | ŋei | *n / A | ||

| you | khyod | well | well | well | * naŋ |

Languages with at least 500,000 speakers

The following table contains all Tibetan Burmese languages with at least 500,000 speakers. The number of speakers, the classification and geographical distribution of these languages are given. This data is based on the web link given below.

The Tibetan Burmese languages with at least 500,000 speakers

| language | Aging. Surname |

speaker | Classification | Main distribution area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burmese | Burmese | 35 million | Lolo-Burmese | Myanmar (Burma); with second speaker 50 million |

| Yi | Yipho | 4.2 million | Lolo-Burmese | South china |

| Tibetan | Ü-Tsang | 2 million | Tibetan | Central and Western Tibet; with Amdo and Khams 4.5 million |

| Sgaw | Sgo | 2 million | Karen | Burma: Karen State |

| Khams | Khams-Tibetan | 1.5 million | Tibetan | Tibet: Kham |

| Meithei | Manipuri | 1.3 million | Manipuri | India: Manipur, Assam, Nagaland |

| Pwo | Pho | 1.3 million | Karen | Burma: Karen State |

| Rakhain | Arakanese | 1 million | Lolo-Burmese | Burma: Arakan |

| Tamang | 1 million | Tamang-Ghale | Nepal: Kathmandu Valley | |

| Bai | Min Chia | 900 thousand | unexplained | China: Yunnan |

| Yangbye | Yanbe | 800 thousand | Lolo-Burmese | Burma |

| Amdo | Amdo-Tibetan | 800 thousand | Tibetan | Tibet: Amdo |

| Kokborok | Tripuri | 770 thousand | Bodo cook | India: Assam |

| Newari | Nepal Bhasa | 700 thousand | Newari thangmi | Nepal: Kathmandu Valley |

| Hani | Haw | 700 thousand | Lolo-Burmese | South China, Burma, Laos, Vietnam |

| Garo | Mande | 650 thousand | Bodo cook | India: Assam |

| Jingpho | Kachin | 650 thousand | Kachin | Bangladesh, Northeast India, North Burma, South China |

| Lisu | Lisaw | 650 thousand | Lolo-Burmese | South China, Burma, Laos |

| Bodo | Bara, Mech | 600 thousand | Bodo cook | India: Assam |

| Pa'o | Taunghtu | 600 thousand | Karen | Burma: Thaung |

| Magar | Kham-Magar | 500 thousand | Magar-Chepang | Nepal: mid west |

| Mizo | Lushai | 500 thousand | Mizo-Kuki-Chin | Northeast India, Burma |

| Karbi | Mikir | 500 thousand | Kuki-Chin-Naga | Northeast India: Assam, Arunachal Pradesh |

| Akha | Ikaw | 500 thousand | Lolo-Burmese | South China, Burma, Laos, Vietnam |

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tibetan languages | About World Languages. Retrieved November 22, 2018 (American English).

- ↑ Christopher I. Beckwith. 1996. "The Morphological Argument for the Existence of Sino-Tibetan". Pan-Asiatic Linguistics: Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Languages and Linguistics, January 8-10, 1996 , Vol. III. Bangkok: 812-826.

- ↑ Denwood, Philip 1986: “The Tibetan noun final -s” Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 9.1, pp. 97-101.

- ↑ Helga Uebach and Bettina Zeisler. 2008. rJe-blas , pha-los and other compounds with suffix -s in Old Tibetan Texts. "In: Brigitte Huber, Marianne Volkart and Paul Widmer (eds.) Chomolangma, Demawend and Kasbek. Festschrift for Roland Bielmeier on his 65th birthday. Birthday, Volume I: Chomolangma. Hall: International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies: 309-334.

literature

- S. Robert Ramsey: The Languages of China . Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1987, ISBN 0-691-06694-9 .

- Paul K. Benedict: Sino-Tibetan. A Conspectus . University Press, Cambridge 1972, ISBN 0-521-08175-0 .

- Scott DeLancey: Sino-Tibetan Languages . In: Bernard Comrie (Ed.): The World's Major Languages . Oxford University Press, New York 1990, ISBN 0-19-520521-9 .

- Austin Hale: Research on Tibeto-Burman Languages . Mouton, Berlin [et al.] 1982, ISBN 90-279-3379-0 .

- James A. Matisoff: Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman . University of California Press, Berkeley [et al.] 2003, ISBN 0-520-09843-9 . ( Free full-text access to the UC Press homepage )

- Anju Saxena (Ed.): Himalayan Languages . Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin [among others] 2004, ISBN 3-11-017841-9 .

- Thurgood, Graham & Randy J. LaPolla: The Sino-Tibetan Languages . Routledge, London [et al.] 2003, ISBN 0-7007-1129-5 .

- George van Driem: Languages of the Himalayas . Brill, Leiden [et al.] 2001, ISBN 90-04-10390-2 .