Dutch language

| Dutch (Nederlands) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Kingdom of the Netherlands , Belgium , Suriname , dialectal in France and Germany (see official status ) |

|

| speaker | 24 million (estimated) | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

nl |

|

| ISO 639 -2 | ( B ) dut | ( T ) nld |

| ISO 639-3 |

nld |

|

The Dutch language (Dutch Nederlandse taal ), or Dutch for short (pronunciation: ), is a West Germanic language that is used as mother tongue by around 24 million people worldwide .

Your language area includes the Netherlands , Belgium , Suriname , Aruba , Sint Maarten and Curaçao . It is also a minority language in some European countries, e.g. B. in Germany and France . The mutually understandable Afrikaans spoken by 15 million people in South Africa and Namibia emerged from Dutch. Dutch is the sixth most widely spoken official and working language in the EU and one of the four official languages of the Union of South American Nations .

The spelling of the standard language , Algemeen Nederlands , is determined by the Nederlandse Taalunie . The Dutch studies researches, documents and mediates the Dutch language and literature in their historical and contemporary forms.

Names of the language

Theodiscus, Dietsc and Duutsc

The Franks initially called their language "frenkisk" and the Romance languages were collectively referred to as " * walhisk " . There was also the word " * þeudisk " for the contrast between Latin and the vernacular , but from the beginning ( 786 ) to the year 1000 it was only passed down in the Middle Latin form "theodiscus". Despite its later spread in Latin texts throughout the West Germanic language area, the origin of this word, due to similarities in the sound form, is very likely in the West Franconian (or old Dutch) area of the Franconian Empire. When in the course of the early Middle Ages in the bilingual West Franconia the political and linguistic term "Franconian" no longer coincided, because the Romansh-speaking population also referred to themselves as "Franconian" (cf. French: français), the word "* þeudisk" was used here. for the linguistic contrast to "* walhisk" and a change in meaning took place, whereby the meaning changed from "vernacular" to "Germanic instead of Romanic".

In the early Middle Ages , "* þeudisk" gave rise to two variants of the self-name: "dietsc" and "duutsc". Although "dietsc" was passed down mainly in ancient texts from the south and southwest of the Netherlands and the use of "duutsc" was concentrated in the northwest of the Dutch-speaking area, the meaning was the same. In early medieval texts, “dietsc / duutsc” was still primarily used as a Germanic antonym to the various Romanic dialects.

In the High Middle Ages, however, "Dietsc / Duutsc" increasingly served as a collective term for the Germanic dialects within the Netherlands. The main reason was the regional orientation of medieval society, whereby, except for the highest clergy and the higher nobility, mobility was very limited. Therefore, "Dietsc / Duutsc" developed as a synonym of the Middle Dutch language, although the earlier meaning (Germanic versus Romance) was retained. In the Dutch phrase "Iemand iets diets maken" ("explain something to someone in a clear way") part of the original meaning is retained. Because the Netherlands was most densely populated in the southwest and the medieval trade routes mainly ran across the water, the average Dutchman of the 15th century, despite the geographical proximity of Germany, had a greater chance of hearing French or English than a German-speaking dialect of the German interior. As a result, Dutch medieval authors had only a vague, generalized idea of the linguistic relationship between their language and the various West Germanic dialects. Instead, they mostly saw their linguistic environment in terms of the little regional lects.

Dutch, Duytsch and Nederduytsch

"Nederlandsch" ("Dutch") was first attested in the 15th century and developed into the common name of the Dutch language, alongside the variant of the earlier "dietsc / duutsc", which is now written in New Dutch as "Duytsch". The use of the word "lower" as a description of the delta and lower course of the Rhine is represented in many historical records. It was said of the mythical Siegfried the Dragon Slayer that he came from Xanten in the “Niderlant”, which meant the area from the Lower Rhine to the river mouth. In Old French , the inhabitants of the Netherlands were called Avalois (comparison: “à vau-l'eau” and “-ois”, roughly “downstream-er”) and the dukes of Burgundy called their Dutch possessions the pays d'embas (French : "Lower countries"), a name that is reflected in the Central French and contemporary French as Pays Bas (Netherlands).

In the second half of the 16th century the neologism "Nederduytsch" arose, which in a certain way combined the previous words "Duytsch" and "Nederlandsch" in one noun. The term was preferred by many prominent Dutch grammarians of this century, such as Balthazar Huydecoper , Arnold Moonen, and Jan ten Kate . The main reasons for this preference were the preservation of the Central Dutch “Dietsc / Duutsc” and the inclusion of the geographical name “Nieder-”, which meant that the language could be separated from “Overlantsch” (Dutch: “Oberländisch”) or “Hooghduytsch” (“High German”) . It was also asserted that the Dutch language would gain reputation with the term “Nederduytsch”, since “Nederduytschland” was the usual translation of the Latin Germania Inferior at the time and thus opened up to the prestige of the Romans and antiquity. Although the term "Duytsch" was used in both "Nederduytsch" and "Hooghduytsch", it does not imply that the Dutch saw their language as particularly closely related to the German dialects of southwest Germany. On the contrary, this new terminological difference arose so that one's own language could be distanced from less understandable languages. In 1571 the use of "Nederduytsch" was greatly increased, as the Synod of Emden decided on "Nederduytsch Hervormde Kerk" as the official name of the Dutch Reformed Church . The determining factors in this choice were more esoteric than the aforementioned grammarians. Thus there was a preference among theologians for the omission of the earthly element "-land (s)" and it was noted that the words "neder-" and "nederig-" (Dutch: "humble, simple, modest") correspond to each other not only phonologically, but also in the root of the word are very close.

Dutch as the only language name

Legend:

As the Dutch increasingly referred to their language as “Nederlandsch” or “Nederduytsch”, the term “Duytsch” became less clear and ambiguous. So Dutch humanists began to use "Duytsch" in a way for which "Germanic" would be used today. During the second half of the 16th century, the nomenclature gradually solidified, with "Nederlandsch" and "Nederduytsch" being preferred terms for the Dutch language, and "Hooghduytsch" becoming the constant common expression for today's German language. It was not until 1599 that “Duytsch” (and not “Hooghduytsch”) was used specifically as a term for German for the first time, instead of Dutch or similar Germanic dialects in general. At first the word "Duytsch" retained its ambiguity, but after 1650 "Duytsch" developed more and more into the short form of High German and the dialects in northern Germany. The process was probably accelerated by the presence of many German migrant workers ( Hollandgoers ) and mercenaries in the Republic of the United Netherlands and the centuries-old use of the terms “Nederlandsch” and “Nederduytsch” over “Duytsch”.

Although "Nederduytsch" briefly surpassed the use of Nederlandsch in the 17th century , it remained largely an officious, literary and scientific term for the general population and began to lose ground in written sources from 1700 onwards. The proclamation of the Kingdom of the United Netherlands in 1815 , which made it clear that the official language of the Kingdom was called Nederlandsch and the state church was renamed Nederlandsch Hervormde Kerk , marked a huge decline in the already dimmed use of the word. With the disappearance of the term Nederduytsch remained Nederlandsch (occupied since the 15th century) as the only proper name of the Dutch language.

In the late 19th century, Nederduits was taken back into the Dutch language as a borrowing back from German, when influential linguists such as the Brothers Grimm and Georg Wenker used this term in the nascent German studies as a collective name for all Germanic languages that did not use the Second Took part in sound shifting . Initially this group consisted of Dutch, English, Low German and Frisian, but within today's Dutch language and linguistics this term is only used for the Low German varieties , especially for the dialects of Low German in Germany, since the Low German dialects in the eastern Netherlands as Nedersaksisch ("Lower Saxon") were designated. The term Diets was also used again in the 19th century as a poetic name for the Middle Dutch language. In addition, Diets is only used by Flemish-Dutch irredentist groups in today's Dutch .

Names of Dutch in other languages

In German, the Dutch language is sometimes colloquially called "Dutch". When the Dutch but in the true sense, it is only a dialect in the western Netherlands in the (historical) region Holland is spoken. This informal language name is known in many European languages, such as French , Spanish , Danish , Italian and Polish , and in some, especially East Asian languages such as Indonesian , Japanese and Chinese , the official name of Dutch is derived from "Holland".

In English and Scots , the name of the Dutch language ("Dutch") has its origin in the word "dietc / duutsc".

Origin and development

Genetic classification of Dutch

The Dutch language is considered a direct continuation of the Old Franconian language. In historical linguistics, Old Franconian is usually divided into two language groups: West Franconian (for example the area between Loire and Maas ) and East Franconian, with its core area mainly along the Middle Rhine . In stark contrast to West Franconian, the second sound shift prevailed in the East Franconian area , according to which these Germanic varieties developed into the forerunners of the West Central German dialects from the 7th century . Since a language assimilation process began in the early Middle Ages among the West Franconians in what is now northern France, with the Germanic-Romance language border moving ever further north and West Franconian being replaced by Old French , the Dutch language is considered to be the only surviving modern variant of the language of the West Franks.

The derivation of Dutch from Old Franconian should not be seen as isolated branches of a tree diagram, but rather in the context of Friedrich Maurer's wave theory . Within this theory, Old Franconian and Old Dutch are viewed as a further development of one of three linguistic innovation centers within the Central European Germanic dialect continuum at the beginning of the first millennium. These language areas, divided by Maurer into Weser-Rhine , Elbe and North Sea Germanic , were not separated from each other, but influenced each other and merged. Therefore, although the old Dutch language as a whole is definitely a further development of the Weser-Rhine group, there are also some typical North Sea Germanic features in western Dutch dialects. This framework is similar to the three-way division of the Continental West Germanic by Theodor Frings , with Dutch being referred to as "Inner Germanic" in contrast to "Coastal Germanic" (Low German, English, Frisian) and "Alpine Germanic" (German).

The modern language varieties of Dutch in the narrower sense, including the Lower Rhine dialects within Germany, are generally classified as " Lower Franconian" in contemporary Germanic philology , a term that refers to the low-lying area of Franconian adopted in the 19th century Settlement area.

In the past, Dutch and Low German were sometimes presented as a common group, as both language groups did not participate in the second phonetic shift. Modern linguistics rejects this model, however, because this division is not characterized by common innovations, but rather represents a residual class. Outside of the professional world, this outdated model can still be found frequently.

Outsourcing of Dutch from Germanic

The separation and constitution of Dutch from Germanic can be understood as a threefold process of linguistic history:

- In the 4th to 7th centuries: increasing differentiation from the late Common Germanic via the South Germanic to the Rhine-Weser Germanic.

- In the 5th to 8th centuries: intensive contacts between a coastal dialect with North Sea Germanic features and the old Franconian dialects of the interior / early Dutch.

- In the 8th to 9th centuries: Assimilation of this coastal dialect by the dialects of the interior / Late Old Dutch.

| Rhine-Weser Germanic | North Sea Germanic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Franconian |

(Ginger dialect ) coastal dialect |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Dutch | Old Frisian | Old English | Old Saxon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Linguistic distance to other Germanic languages

The West Frisian language and Afrikaans are most similar to Dutch. Afrikaans, which emerged from New Dutch , is the most closely related language in terms of orthography and understanding of individually pronounced words. In terms of the intelligibility of longer spoken texts, however, it is easier for Dutch speakers to understand Frisian than Afrikaans. The reason for this close relationship is that Frisian and Dutch have been in close linguistic contact for centuries, which means that modern Frisian vocabulary contains a great deal of Dutch loanwords.

The English, Low German and German languages are also related to Dutch as West Germanic languages. With regard to the German-Dutch language affinity, mutual intelligibility is limited and is particularly present in the written language. When the spoken languages are compared, most studies show that Dutch speakers understand German better than the other way around. It is unclear whether this asymmetry has linguistic reasons or is due to the fact that a significant number of Dutch speakers learn German (and / or English) as a foreign language in secondary schools, since studies with German and Dutch children without knowledge of foreign languages have also shown that German Children understood less Dutch words than the other way around. When it comes to mutual intelligibility, there are also big differences between related and unrelated words . In almost all studies on mutual understandability, the German and Dutch standard languages are compared. The mutual intelligibility between Standard German and Dutch dialects (or Standard Dutch and German dialects) is generally negligible.

The increased mutual intelligibility between Dutch and Low German, instead of between Dutch and German, is sometimes assumed to be proven, since both language groups did not take part in the second sound shift. However, research shows that standard German is easier to understand for Dutch speakers than Low German. In the direct border area, the Dutch could understand the Low German speakers a little better, but they still understood Standard German better than Low German.

Historical perception of Dutch in German studies

From the late 18th century to the beginning of the 20th century, the German perception of the Dutch language was predominantly determined by a negative attitude towards all Dutch. From the point of view of early German German studies , Dutch was viewed unilaterally as being in the 'outskirts', as the language of a 'residual area'. In addition, a name myth arose in German German studies from the early phases of German studies up to the 1970s, with the frequent use of "German" in the sense of "Continental West Germanic". The old conglomerate of dialects, from which the two modern cultural languages German and Dutch, which today cover the continuations of these dialects, were equated with the first and more important of these two languages. This unclear use of the language has damaged the reputation of Dutch in the German-speaking area: the opinion that Dutch is "a kind of German", or that it used to be part of German or that it somehow emerged from German, is found in popular discourse, thanks to the myth of names and the frequent reprints of outdated manuals, it still appears sporadically in the German-speaking area today.

history

Legend:

The language history of Dutch is often divided into the following phases:

-

Old Dutch (approx. 400–1150)

- Early Dutch (approx. 400–900)

- Late Old Dutch (approx. 900–1150)

-

Middle Dutch (approx. 1150–1500)

- Early Middle Dutch (approx. 1150-1300)

- Late Middle Dutch (approx. 1300–1500)

-

New Dutch (1650-1800)

- Early Dutch (approx. 1500–1650)

Old Dutch

As Old Dutch language is called the oldest known language level of Dutch. It was spoken from about 400 to 1150 and has only survived in fragments. Like its successor, the Middle Dutch language , it was not a standard language in the true sense of the word. In the literature, the terms "Old Dutch" and "Old Franconian" are sometimes used synonymously, but it is more common and more accurate to speak of Old Dutch from the 6th century onwards , as Old Franconian was divided into a postponed and an unshifted variant during this period. The sub-category "Old West Franconian" is largely synonymous with Old Dutch, as there is no shifted form of West Franconian.

The area in which Old Dutch was spoken is not identical to today's Dutch-speaking area: Frisian and related North Sea Germanic ("Ingwaeon") dialects were spoken in the Groningen and Friesland areas as well as on the Dutch coast . In the east of today's Netherlands ( Achterhoek , Overijssel , Drenthe ), Old Saxon dialects were spoken. In the south and southeast, the Old Dutch-speaking area at that time was somewhat larger than the N-Dutch language today: French Flanders and part of the area between the province of Limburg and the Rhine were then part of the Dutch-speaking area.

In Old Dutch, some sound changes took place in the 8th century that did not prevail in the other West Germanic languages. The most important changes are shown in the table below:

| Old Dutch language development | Dutch language example | Correspondence in other West Germanic languages | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| The consonant connection -ft changed to -cht in Old Dutch . | sti cht en de lu cht (op) li cht en |

sti ft en (German) die Lu ft (German), de lo ft (West Frisian) to li ft (English) |

Cognate, no translation. |

| The cluster -ol / -al + d / t became -ou + d / t. | k ou d |

k al t (German), c ol d (English), k âl d (West Frisian), k ol t (Low German) | |

| The lengthening of short vowels to open, stressed syllables in the plural. | dag, dagen [d ɑ ɣ], [d aː ɣən] |

Day, days (German) [ˈt aː k], [ˈt aː ɡə] |

|

| Storage of the voiced velar fricative from ancient Germanic . | ei g s, [ɛɪ ɣ ən] | * ai g anaz, [ɑi̯. ɣ ɑ.nɑ̃] (Ur-Germanic) ei g en, [aɪ ɡ ɛn] (German) |

The following example shows the development of the Dutch language based on an old Dutch text and a Middle Dutch reconstruction:

| Language level | sentence | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| Old Dutch | Irlôsin sol an frithe sêla mîna fan thēn thīa genācont mi mi, wanda under managon he was mit mi. | The original text from the Wachtendonck Psalms (54.19) of the 9th or 10th century. |

| Old Dutch | Mîna sêla [inde] fan thên thia mi ginâcont sol an frithe irlôsin, wanda under managon was he mit mi. | The original text was partly drawn up using Latin syntax and is represented here with a (reconstructed) Germanic sentence structure. |

| Middle Dutch | Redeem sal [hi] to vrede siele mine van dien die genaken mi, want onder menegen hi was met mi. | Verbatim reconstruction of the original text in Middle Dutch of the 13th / 14th centuries. |

| Middle Dutch | Hi sal to vrede mine siele [ende] van dien redeem the mi genaken, want onder menegen what hi met mi. | Translation with Central Dutch syntax. |

| Dutch | Hij zal in vrede mijn goal en van hen / who left the mij genaken, want onder menigen what hij met mij. | Dutch translation of the old Dutch text. |

| German translation | He will redeem my soul and its near me (i.e. my soul) in peace because among some he was with me. |

Middle Dutch

Although many more manuscripts appeared in Middle Dutch than in Old Dutch and this sets the limit in time, the difference between the two languages is primarily defined by language. In terms of grammar, Middle Dutch takes a middle position between the heavily inflected Old Dutch and the more analytical New Dutch. The inflection of the verbs is an exception within this process, as far more verbs were strong or irregular in Middle Dutch than in New Dutch. In the area of phonetics , Middle Dutch differs from Old Dutch by the weakening of the secondary tone vowels . For example, vogala became vogele ("birds", in modern Dutch: vogels ). The Central Dutch language was written phonetically to a large extent, with the texts often being influenced by a particular dialect.

Middle Dutch is divided into five main dialects: Flemish , Brabantian , Dutch , Limburgish, and East Dutch . These dialect groups each have their own characteristics, with the peripheral dialects (East Dutch and Limburgish) also showing some typical influences of Lower Saxony and German. In the beginning, Eastern Dutch developed on the basis of Old Saxon instead of Old Dutch; However, it was so strongly influenced by the Central Dutch writing tradition that this form of language is considered to be Central Dutch with a constantly decreasing Lower Saxony substrate. The Lower Saxon dialects in the county of Bentheim and in East Friesland were also heavily influenced by Middle Dutch. Limburgish, on the other hand, in its Central Dutch form, took over some features of the neighboring Ripuarian dialects of German, with the influence of the city of Cologne being of great importance. In the Dutch, this expansion of Central Franconian characteristics within Limburg is traditionally referred to as “Keulse expansie” (Cologne expansion). Around 1300 the Ripuarian influence declined and the Limburg varieties were mainly influenced by the Brabantian.

Overall, however, Middle Dutch was dominated by the Flemish, Brabant and Dutch dialects, whose speakers made up around 85–90% of the total speakers. Cities in the south of the Netherlands such as Bruges , Ghent and Antwerp developed into trading centers in the High Middle Ages . In this highly urbanized area is a developed from the southwestern Flemish Brabant and dialects, balancing language . The literary Middle Dutch of the 13th century is predominantly shaped by this language of equilibrium, with Flemish characteristics being most strongly represented. This was due to the strong influence that the Flemish Jacob van Maerlant exerted on the literature of his time. In the 14th century, the linguistic basis of literary Middle Dutch shifted to Brabant and this dominant role of Brabantian intensified in the 15th century. This shift in the linguistic basis led to language mixing and the emergence of a language that could be used interregionally.

Important works of Central Dutch literature are:

- Van den vos Reynaerde , an animal poem in verse that tells of a cunning fox.

- The Roelantslied , a Central Dutch adaptation of the old French verse epic about the heroic end of the Franconian Hruotland .

- The Brabantsche Yeesten , a rhyming chronicle from the first half of the 14th century with more than 46,000 verses.

- Karel ende Elegast , a courtly novel about Charlemagne and an elf king.

- Der naturen bloeme , the first nature encyclopedia in Dutch, based on the Latin model of De natura rerum by Thomas von Cantimpré .

New Dutch

From a linguistic perspective, New Dutch is the most recent form of Dutch. It has been spoken since around 1500 and forms the basis of the standard Dutch language .

Typical characteristics of New Dutch compared to Middle Dutch are:

- Extensive deflection , in particular the weakening of the case system . While Middle Dutch is a highly inflected language, more and more prepositions are used instead in New Dutch .

- The double negation disappears from the written language, although it still exists in various dialects of Dutch and Afrikaans.

- A sound shift in the range of the diphthongs [ie] and [y], which were then pronounced as [ai] and [oi]. Compare mnl: "wief" and "tuun" with nnl : "wijf" and "tuin".

- The emergence of a supraregional written language based on the Brabant dialect and, from the 17th century , also with Dutch influences.

Origin of the standard language

Although certain regional writing preferences can already be shown in Central Dutch, the written language of Central Dutch did not yet have any fixed spelling rules or fixed grammar. The words were spelled phonetically and therefore Central Dutch texts are mostly strongly influenced by the author's dialect. With the emergence of the printing press in the middle of the 15th century , through which a large audience could be reached, there was more uniformity in the spelling of Dutch.

In 1550, the Ghent printer and teacher Joos Lambrecht published the first-known spelling treatise ( Nederlandsche spellynghe , "Dutch Spelling"), in which he proposed a standard spelling based on both pronunciation and morphological principles. In 1584 Hendrik Laurenszoon Spiegel formulated a number of published spelling rules to unify and maintain the tradition, which, under the name Twe-spraack , was long considered the most important grammar of the United Netherlands . The Statenvertaling Bible translation of 1618 could have largely standardized Dutch spelling in the early 17th century because of its widespread use in civic education. The translators, however, did not always agree with each other and sometimes allowed different spellings of the same word, and uniformity hardly played a role, which means that the translation of the Bible had little effect on the standardization of the language.

Codification of the standard language

legend:

The first official regulation of spelling in the Netherlands dates back to 1804. After the proclamation of the Batavian Republic , an opportunity was seen to come to a uniform spelling and grammar. The Leiden linguist Matthijs Siegenbeek was commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Education in 1801 to write uniform spelling.

When the Kingdom of Belgium was founded in 1830 , Siegenbeeks 'spelling was rejected as "Protestant", as a result of which Jan Frans Willems' spelling was introduced in Belgium in 1844 . In 1863, the spelling of De Vries and Te Winkel, designed by the authors of the historical-linguistic Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal , appeared . This spelling treatise was introduced in Flanders in 1864 , in the Netherlands in 1883 and is considered the basis of today's Dutch spelling.

Standard Dutch is not a record of a specific Dutch dialect, but a hybrid form of largely Flemish, Brabant and Dutch major dialects that has been cultivated over centuries. Before the advent of mass education and general schooling in the Netherlands and Flanders, standard Dutch was primarily a written language in most social classes. There is no uniformly coded pronunciation regulation for written Dutch, such as Received Pronunciation in English or historical stage German in German. The standard Dutch language is thus a monocentric language in terms of orthography with only one official spelling in all Dutch-speaking countries, but the pronunciation and choice of words are quite different. These are not only differences between Belgian Standard Dutch and Standard Dutch in the Netherlands, but also at the regional level.

Secession of the Afrikaans

The spelling of De Vries and Te Winkel was also introduced in the South African Republic in 1888 , but it was often at a greater distance from the partially creolized everyday language of the Africans . In 1875 the Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners was founded with the aim of establishing Afrikaans as a written language. The spelling reform propagated in 1891 by the Dutch linguist Roeland Kollewijn with an emphasis on phonetic spelling was mostly perceived as "too modernist" or "degrading" in the Netherlands and Belgium. In South Africa, however, Kollewijns Vereenvoudigde Nederlandse spelling (German: simplified Dutch spelling) was introduced as the official spelling of the Dutch language in 1905 and served as the basis for the Afrikaans spelling from 1925 .

Until 1961 , the Great Dictionary of the Dutch Language also contained words that were only used in South Africa, with the addition of "Afrikaans" (African).

Distribution and legal status

Dutch as the official and mother tongue

Around 21 million people currently speak a variant of Dutch. In Europe, Dutch is the official language in Belgium and the Netherlands. In addition, around 80,000 residents of the French department of the North speak a Dutch dialect.

The Netherlands and Belgium created the so-called Dutch Language Union (Nederlandse Taalunie) on September 9, 1980 . This is to ensure that a common spelling and grammar continues and the language is maintained. Of course, there are regional peculiarities between the Dutch and the Belgian variant of the standard language.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, around seventeen million people speak Dutch as a first or second language.

The Basic Law of the Netherlands does not contain any provisions on language use in the Netherlands and Dutch is not mentioned in the text. In 1815, King Wilhelm I made Dutch the only official language of the entire empire by decree. In 1829 this decree was withdrawn and a year later Dutch became the official language for the provinces of North Brabant, Gelderland, Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Friesland, Overijssel, Groningen and Drenthe, while French was the official language for the provinces of Limburg, East and West Flanders and Antwerp and the administrative districts of Leuven and Brussels. After the Belgian Revolution , Dutch also became the official language in the Dutch part of Limburg. It was not until 1995 that the status of Dutch as the official language was legally confirmed by an amendment to the General Administrative Act:

Chapter 2, Paragraph 2.2, Art. 2: 6:

Administrative bodies and persons working under their responsibility use the Dutch language, unless otherwise stipulated by law.

Belgium

In Belgium, more than half the population (over five million) is Dutch-speaking.

The language legislation regulates the use of the three official languages Dutch, French and German in Belgian public life. While Article 30 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Belgium provides for the free use of languages for private individuals, the public services of the state must observe a number of rules that affect the use of languages within the services as well as between the various services and towards the citizen. In particular, language laws are addressed to legislators, administrations, courts, armed forces and teaching staff in Belgium.

Belgian language legislation is one of the consequences of the Flemish-Walloon conflict that has arisen since the beginning of the Flemish Movement in the mid-19th century between the Dutch- speaking Flemings in northern Belgium and the French-speaking Walloons in the south. The aim of these laws was a gradual equality of the Dutch and French languages.

Suriname

Dutch is the official language of the Republic of Suriname . Suriname has around 400,000 Dutch-speaking residents and around 100,000 Surinamans have a command of Dutch as a second language. The Dutch spoken in Suriname can be seen as a separate variant of Dutch, as it was influenced in vocabulary, pronunciation and grammar by the other languages spoken in Suriname, especially Sranan Tongo .

Since December 12, 2003, Suriname has also been a member of the Nederlandse Taalunie, created in 1980 by the Netherlands and Belgium .

Caribbean Islands

In the special Caribbean communities of the Netherlands Bonaire , Sint Eustatius and Saba , as well as the autonomous countries Aruba , Curaçao and Sint Maarten , Dutch is the official language. However, only a minority of the population speak Dutch as their mother tongue. On Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao, Dutch is the lingua franca in business and formal areas, while Dutch on Saba, Sint Eustasius and Sint Maarten is primarily a language of instruction and is a second language of the population.

Dutch as the former official language

South Africa and South West Africa

Between 1910 and 1983 Dutch was one of the official languages of the South African Union and the South African Republic and, from 1915, also in South West Africa (today: Namibia ), where South African law applied. In 1961 a law stipulated that the terms “Dutch” and “Afrikaans” were to be regarded as synonyms within the meaning of the South African constitution. Since 1994 Afrikaans is one of the eleven official languages of South Africa and, since independence in 1990, English is the only official language of Namibia.

Dutch East Indies

In sharp contrast to the language policy in Suriname and the Caribbean , there was no attempt by the colonial government in today's Indonesia to establish Dutch as a cultural language: the lower echelons of Dutch colonial officials spoke Malay to the local rulers and the general population. The Dutch language was strongly identified with the European elite and Indo-Europeans (descendants of Dutch people and local women) and was not taught in colonial schools for the upper strata of the local population until the late 19th century . Thus said Ahmed Sukarno , the first president of Indonesia and former student at one of these state schools, fluent in Dutch. In 1949 Dutch did not become the official language of the new Republic of Indonesia, but it remained the official language in West Papua until 1963 .

Dutch language areas without legal status

Outside Belgium and the Netherlands, there are neighboring areas where Dutch dialects are traditionally spoken as the mother tongue, although the dialects are not covered by the standard Dutch language.

Germany

The original dialects of the German Lower Rhine, the western Ruhr area , as well as parts of the Bergisches Land are from a language-typological point of view Lower Franconian or Dutch. In particular, the Kleverland dialects spoken in Germany are considered to be Dutch dialects and were revised by the standard Dutch language until the 19th century.

In the course of the 19th century, however, the Prussian government adopted a rigid, active language policy, the aim of which was the complete displacement of Dutch and the establishment of German as the only standard and written language. Nevertheless, Dutch was secretly spoken and taught in the churches in Klevian until the last decades of the 19th century, so that around 1900 there were still 80,361 Dutch-speaking residents of the German Empire. According to sociolinguistic criteria, the Lower Franconian dialects covered by the German standard language can no longer be counted as Dutch today. Nevertheless, if the pronunciation distances of the German dialects are considered, the Lower Rhine dialect area is geographically and numerically the smallest of the five clusters within Germany.

France

In northern France Nord approximately 80,000 to 120,000 people living with the West Flemish variant of the Netherlands (so-called "live Westhoek-Flemish ") grew up.

Dutch as a migrant language

United States

Dutch is one of the earliest colonial languages in America and was spoken in the Hudson Valley , the former area of the Nieuw Nederland colony, from the 17th to the 19th centuries . For example, the United States Constitution of 1787 was translated into Dutch the following year so that it could be read and ratified by the Dutch- speaking voters of New York State , a third of the population at the time. In New York there are also many street names of Dutch origin, such as Wall Street and Broad Street , but also certain quarters were named after Dutch cities such as Harlem ( Haarlem ), Brooklyn ( Breukelen ) and Flushing ( Vlissingen ) in the New York City District Manhattan .

Martin Van Buren, the eighth President of the United States and, along with Andrew Jackson, the founder of the modern Democrats , spoke Dutch as his mother tongue, making him the only US President to date for whom English was a foreign language.

Although around 1.6% of Americans are of Dutch descent, around 4,500,000 people, the Dutch language is only spoken by around 150,000 people, mostly emigrants from the 1950s and 1960s and their direct descendants.

Canada

In Canada , Dutch is spoken by around 160,000 first or second generation people. These are mainly people (approx. 128,000) who emigrated to Canada in the 1950s and 1960s. They live mainly in urban areas, such as Toronto , Ottawa or Vancouver .

Dutch as a legal language

In Indonesia's legal system, knowledge of Dutch is considered essential in the legal field, as the Indonesian code is mainly based on Roman-Dutch law. While such common law has been translated into Indonesian , the many legal comments required by judges to make a decision have usually not been translated.

Dutch as a foreign language

Language certification

- Certificaat Nederlands als Vreemde Taal (CNaVT) - Certificate of Dutch as a Foreign Language

- Nederlands als tweede taal (NT2) - State examination Dutch as a foreign language

Countries with Dutch classes

Belgium (Wallonia)

In Wallonia , the French-speaking part of Belgium, teaching Dutch is an optional subject in secondary schools. In bilingual Brussels, Dutch is a compulsory subject for all students as a foreign language. Overall, around 15% of Belgians, with French as their mother tongue, speak Dutch as a second language.

Germany

Dutch as a foreign language is in Germany almost exclusively at schools in North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony taught. Because of the geographical distance to the language area, it is rarely offered in the rest of Germany (individual schools in Bremen and Berlin). As a teaching subject , it was established in schools during the 1960s. In North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony, Dutch was taught as a compulsory or compulsory elective subject at various lower secondary schools in the 2018/2019 school year. A total of 33,000 pupils learned Dutch.

Dutch language media

Around 21,000 Dutch-language books are published annually. Around 60 Dutch feature films appear in Dutch and Belgian cinemas every year. The Dutch-language films The Attack , Antonia's World and Karakter won an Oscar in the category of best foreign language film , and eight others were nominated.

Varieties

Dialects

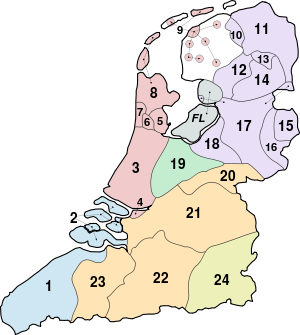

In the area of application of the Dutch cultural language, the spoken dialects can be divided into the traditional main dialect groups of Lower Franconian , Lower Saxon and Ripuarian .

The dialect divisions of Dutch from the early 19th century were based primarily on the assumed division of the population into Frisian , Saxon and Frankish old tribes . Therefore, the Dutch language, which also included Frisian at the time, was divided into three "pure language groups" (Franconian, Frisian, Saxon) and three "mixed groups" (Friso-Saxon, Franco-Saxon and Friso-Franconian). Later in the 19th century, under the great influence of the German linguist Georg Wenker and his Wenker sentences , there was a long period in which isoglosses , preferably collections of isoglosses, dominated the structure of dialects on a regional level. In the 1960s there were attempts to divide the dialects on a sociolinguistic basis as well, with dialect speakers being asked with which dialect or dialect they most identified their own dialect. Since the 21st century , the focus has been on the analysis of large amounts of data in the areas of grammar, phonology and idioms using computer models such as the feature frequency method .

Definition according to relationship

According to the criterion of relationship, Dutch is equated with Low Franconian and two main groups and different subgroups can be specified:

- West Lower Franconian (South, West and Central Dutch)

- South Lower Franconian (Southeast Dutch)

Definition according to roofing

According to the criterion of the canopy, the dialects are Dutch, which are related to Dutch and which are spoken where Dutch - and not a more closely related language - is the cultural language. According to this definition, the Lower Saxon dialects (such as Gronings and Twents ) in the northeast of the Netherlands also belong to the Dutch dialects, as well as the Ripuarian varieties that are spoken in a small area around Kerkrade , in the extreme southwest of the Netherlands. The restriction “no closely related language” in this criterion is necessary in order to distinguish between the Frisian and Dutch dialects, since both Standard Dutch and Standard Frisian are cultural languages in the province of Friesland.

In practice, this definition is consistent with the sociolinguistic point of view common in the Netherlands and Belgium , with all language varieties within the language area of the standard Dutch language being considered as "Dutch dialects".

Creole languages based on Dutch

Live

- Afrikaans ( South Africa and Namibia )

Extinct or moribund

- Berbice-Dutch ( Guyana )

- Skepi (Guyana)

- Negro Dutch ( Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico )

- Petjo , ( Indonesia )

- Javindo , (Indonesia)

- Ceylon Dutch ( Sri Lanka )

- Mohawk Dutch ( United States )

- Jersey Dutch (United States)

- Albany Dutch (United States)

Dictionary

The Great Dictionary of the Dutch Language (Groot woordenboek van de Nederlandse taal) contains over 240,000 headwords. The Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal ( German dictionary of the Dutch language ), a very extensive historical-linguistic dictionary with all documented Dutch words since the 12th century, even contains over 400,000 keywords. The language database of the Institute for the Dutch language, with all known word forms of the contemporary language, contains around 7,000,000 lexemes. However, depending on the source and counting method, the total scope of the Dutch vocabulary is estimated at 900,000 to 3,000,000 words or lexemes .

Foreign and loan words in Dutch

Most loan words in Dutch come from the Romance languages (mainly French and Latin ). A review of the Etymological Dictionary of the Dutch Language, which describes a total of 22,500 Dutch loanwords, showed that 68.8% of the words have a Romance origin. 10.3% was borrowed from English, 6.2% from German. The use of loanwords in Dutch texts and the spoken language is difficult to estimate. For example, a newspaper text from the NRC Handelsblad , in which every different word was counted once, consisted of around 30% loan words. However, only 15 of the 100 most used Dutch words are loan words.

Furthermore - unusual for a European language - most of the common words in some areas of science in Dutch are not borrowed from Greek or Latin:

| Dutch | German | Literal translation |

|---|---|---|

| science | mathematics | "Certainly customer" |

| meet customer | geometry | "Measurement" |

| wijsbegeerte | philosophy | "Desire for wisdom" |

| certificate of nature | physics | "Natural history" |

| geneskunde | medicine | "Genes [ungs] customer" |

| sheikunde | chemistry | "Scheidekunde" |

Dutch foreign and loan words in other languages

Many languages have borrowed parts of their vocabulary from Dutch. The Dutch linguist Nicoline van der Sijs lists 138 such languages. More than 1000 words have become at home in 14 languages. These are: Indonesian (5568), Sranantongo (2438), Papiamentu (2242), Danish (2237), Swedish (2164), (West) Frisian (1991), Norwegian (1948), English (1692), French (1656 ), Russian (1284), Javanese (1264), German (1252) and Manado- Malay (1086; a Creole language spoken in Manado ). There were 3,597 loans in the now extinct Creole language of Negro Dutch .

In German

In relation to the total volume of all foreign-language loanwords in the text corpus of the German language, the proportion of Dutch from the 12th to the 17th centuries is between 3 and 4%. In the 18th century the proportion is only 1.2% and in the 19th century it continued to decline by 0.4%, so that in the 20th century borrowings from Dutch hardly play a role in the overall range of all foreign-language loanwords. Nevertheless, certain language areas of German are strongly influenced by Dutch, so there are many borrowings, especially in the seaman's language , such as the words " sailor ", hammock or " harpoon ", and in the names of various marine animals such as " cod ", " " Shark ", " Mackerel ", " Sperm Fish ", " Walrus ", " Kipper " and " Shrimp ".

Some German words, such as “ Tanz ” and “ Preis ”, are ultimately French in origin, but were influenced by Dutch, especially in the Middle Ages, before they reached the German-speaking area.

The Dutch language had a particularly great influence on the East Frisian dialects , whose vocabulary contains many loanwords from Dutch, and on the Low German dialects in general.

In English

The Dutch influence on British English is particularly evident in the area of nautical and economic terms (such as freight , keelhauling , yacht ). In American English , Dutch foreign words are represented more strongly and more diverse thanks to the Dutch colonial history. Examples of well-known Dutch-origin words in American English are cookie , stoop , booze , coleslaw , boss , dollar, and Santa Claus .

In West Frisian

Although Frisian was used in most written sources from 1300 onwards , at the end of the 15th century the Dutch language took over the role of the written language of Frisia . It was not until the 19th century that attempts were made to create a West Frisian cultural language. For centuries, the Dutch and Frisian languages coexisted side by side, with Dutch being the language of the state, the administration of justice, the church and teaching, while Frisian was mainly spoken within the family and in the country. The influence of Dutch on the Frisian language is profound and relates not only to borrowings from Dutch, but also to grammatical developments within Frisian.

Proverbs and metaphors

The Dutch language is rich in proverbs, idioms, metaphors and idioms . Well-known Dutch proverb lexicons include the “Spreekwoordenboek der Nederlandse taal” and the “Van Dale spreekwoordenboek”, the latter book containing around 2500 proverbs. Dutch proverbs borrowed from the Bible or the classics often have a German equivalent, but idioms from the Central Dutch literary tradition or contemporary cultural language often lack a clear literal translation. For example, a comparative study between German and Dutch priamels , a kind of poem , showed that out of 77 researched Dutch priamels, 44 had no German-language equivalent. In comparison to German, English or French, idiomatic expressions are more common in Dutch. The Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga even interpreted the frequent use of proverbs in Dutch as an anachronistic remnant of the medieval expressive culture, which, in contrast to the French and German cultures, was suppressed to a lesser extent during the Enlightenment due to its assumed diffusiveness or connoted with popularity.

Pejorative

The frequent use of diseases as insults is peculiar to Dutch swearwords . In addition to diseases, pejorative vocabulary is mainly based on genitals and sexuality . Comparisons with animals or faeces are rare. Diseases that are constantly used as a swear word in Dutch include: a. "Kanker" ( cancer ), "tering" ( tuberculosis ) and "klere" ( cholera ), whereby these diseases are often found in a combination with "-lijer" (sufferer). The words "kut" (vagina) and "lul" ( penis ) are also used in many compositions , for example in "kutweer" (bad weather) or "kutlul" (asshole).

Insults in the imperative form are formed in Dutch with the preposition "op" (auf):

| Dutch | Literally | Idiomatic translation |

|---|---|---|

| Kanker op! Flikker op! Lazer op! Donder op! Pleur op! |

"Cancer on" " Gay on" " Leprosy on" " Thunder on" " Pleurisy on" |

Fuck off! |

The above-mentioned imperatives can also be used as transitive verbs in Dutch , for example in the sentence "Lotte flikkerde van het podium." (Literally: Lotte gay-te from the stage, ie she fell) after which the meaning changes to , differently vulgar, synonyms of the verbs fall or plunge.

Cognate relationship with other West Germanic languages

Classification of false friends according to Kroschewski (2000):

| Kind of interlingual false friend | definition | Dutch example | Translation into German and related languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthographically | In the case of interferences in the area of orthography, the shape of two words is perceived as so similar that the learner either does not perceive the deviating elements or does not remember them in a specific situation. However, many spelling mistakes are hardly a problem for the language processor. |

direct de vriend |

German: direct English: the friend (der Freund) |

| Phonological | These false friends include words with features that are prone to interference in the area of pronunciation due to the interlingual similarity of the linguistic signs, although they do not contain a different word meaning. | bad / [bɑt] register / [rʏ'ɣɪstər] |

German: Bad [ba: t] English: register / [ˈrɛʤɪstə] |

| Morphologically | In the case of morphologically false friends, there are formal divergences, for example in the formation of the plural or the use of prefixes. | afdwingen de boot, de boten week, weken |

German: force German: the boat, the boats English: week, weeks (week, weeks) |

| Semantically | Semantic false friends include words with a similar shape with stylistic differences, for example a higher or lower style level. | sake forceren |

German: "want", but also in the sense of "want" English: to force |

| Semi-honest | Semi-honest false friends are words that partially overlap or overlap, but each lexeme in the respective individual language has additional meanings that the lexeme of the same form in the other language does not have. | afstemmen kogel |

German: “vote”, but not “choose”. German: "Kugel", but not "Sphäre" |

| Dishonest | In this group of words, the two word meanings refer to completely different referents. | bark durven de gift |

German: call, ring the bell German: dare German: the present |

| Syntactically | In the case of a syntactic wrong friend, the similarity of a word in the construction of a sentence in the foreign language means that the syntactic structure is adapted to that of the source language. | Ik heb interest in Ik ben vergeten |

German: I'm interested in (not "in") I forgot (with "haben" instead of "sein") |

| Idiomatic | In idiomatic expressions, the meaning cannot be understood from the meaning of the individual words. | De hond in de pot find | German: literally: "Find the dog in the pot", analogously. "Finding [only] empty [food] bowls" |

| Pragmatic | With this speech defect, there is a lack of linguistic and cultural prior knowledge and world knowledge, which means that no appropriate language behavior occurs. | "Lieve [X]," as a translation of "Lieber / Liebe [X]," at the beginning of the letter | “Lieve” means “sweet”, Lieber / Liebe is translated as “best”. |

spelling, orthography

Dutch spelling is largely phonematic . The distinction between open and closed syllables is of fundamental importance in Dutch , with the long vowels being written singly in open syllables and doubled in closed syllables.

Letters

A Latin writing system is used to write Dutch . The 26 basic letters are identical to the letters of the modern Latin alphabet :

| Capital letter | Lowercase letter | Letter name (full) |

Pronunciation ( IPA ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. | a | a | / a / |

| B. | b | bee | / be / |

| C. | c | cee

lake |

/ se / |

| D. | d | dee | / de / |

| E. | e | e | / e / |

| F. | f | ef | / ɛf / |

| G | G | gee | / ɣe / |

| H | H | haa | /Ha/ |

| I. | i | i | / i / |

| J | j | yeah | / each / |

| K | k | kaa | / ka / |

| L. | l | el | / ɛl / |

| M. | m | em | / ɛm / |

| N | n | en | / ɛn / |

| O | O | O | /O/ |

| P | p | pee | / pe / |

| Q | q | quu | / ky / |

| R. | r | he | / ɛr / |

| S. | s | it | / ɛs / |

| T | t | tea | / te / |

| U | u | u | / y / |

| V | v | vee | / ve / |

| W. | w | wee | / ʋe / |

| X | x | ix | / ɪks / |

| Y | y | Griekse y ij i-grec |

/ ˈƔriksə ɛɪ̯ / / ɛɪ̯ / / iˈɡrɛk / |

| Z | z | zet | / zɛt / |

Besides the doubled vowels and consonants , the following digraphs are common: au, ou, ei, ij, ui, oe, ie, sj, sp, st, ch, ng and nk .

Large and lower case

In the Dutch language, all parts of speech are generally lowercase, only the first word of a sentence is capitalized. Exceptions to this rule are names of various kinds:

- First names and surnames.

- Geographical names (countries, places, rivers, mountains, celestial bodies) and adjectives derived from geographical names .

- Names of languages and peoples and their adjectives .

- Institutions, brands , and work titles .

- As a sign of respect.

Phonology

Pronunciation of Dutch

Monophthongs

| IPA | Word example | German equivalent | annotation | Audio sample

(clickable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ɑ | b a d | - |

engl. calm (calm) [ kʰ ɑ ːm ] French âme (soul) [ ɑ m ] Persian دار (gallows) [ d ɑ ɾ ] |

|

| ɛ | b e d | k e ss | ||

| ɪ | v i s | M i tte | ||

| ɔ | b o t | t o ll | ||

| ʏ | h u t | N ü sse | ||

| aː | aa p | a ber | ||

| eː | e zel | g eh s | ||

| i | d ie p | M ie te | ||

| O | b oo t | o the | ||

| y | f uu t | G u te | ||

| O | n eu s | M er re | ||

| u | h oe d | - | French fou (crazy) [ f u ] |

|

| ə | hem e l | Nam e |

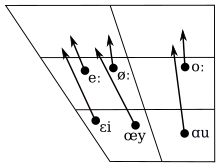

Diphthongs

| IPA | Word example | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| ɛɪ̯ | b ij t, ei nde | |

| œʏ̯ | b ui t | |

| ʌu | j ou , d auw | Belgian-Dutch: ɔʊ̯ |

| ɔi | h oi | |

| o: ɪ̯ | d ooi | |

| iu | n ieuw | |

| yʊ̯ | d uw | |

| ui | gr oei | |

| a: ɪ̯ | dr aai | |

| e: ʊ̯ | sn eeuw |

Consonants

| IPA | Word example | German equivalent | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| b | b eet | B all | |

| d | d ak | d ann | |

| f | f iets | Ha f t | |

| ɣ | g aan | - |

arab. غرب (west) [ ɣ arb ] span. Paga (wages) [ ˈpa ɣ a ] neo-Greek. γάλα (milk) [ ɣ ala ] |

| ɦ | h ad | - |

Ukrainian гуска (goose) [ ɦ uskɑ ] Igbo aha (name) [ á ɦ à ] |

| j | y as | j er | |

| k | k at, c abaret | k old | Realized not aspirated. |

| l | l and | L atte | |

| m | m at | M atte | |

| n | n ek | n ass | |

| ŋ | e ng | ha ng | |

| p | p en, ri b | P ass | Realized not aspirated. |

| r | r aar | - |

span. perro (dog) [ pe r o ] Russ. рыба (fish) [ r ɨbə ] ungar. virág (Blume) [ vi r AG ] |

| s | s ok | Nu ss | |

| t | t ak, ha d | al t | Realized not aspirated. |

| v | v he | - | Half-voiced labiodental fricative, a half-voiced middle thing between [f] and [v]. |

| ʋ | w ang | - |

engl. wind (wind) [ w ɪnd ] French. coin (corner) [ k w ɛ ] Pol. łódka (boat) [ w utka ] ital. uomo (man, man) [ w ɔːmo ] |

| x | a ch t | la ch s | German standard pronunciation of -ch after a, o, u . |

| z | z on | S suspect | |

| c | tien tj e | - |

Hungarian : tyúk [ c UK ] (chicken) Polish : polski [ pɔls c i ] (Polish) |

| ɡ | g oal | G ott | |

| ɲ | ora nj e | - |

French : si gn e [ si ɲ ] (characters) Italian : gn occhi [ ˈɲɔkːi ] (cam) |

| ʃ | ch ef, sj abloon | sch nell | |

| ʒ | j ury | G enie | |

| ʔ | b eë indig | b ea Want | Crackling sound produced by the glottal closure. |

- The individual syllables are connected through, so that the glottic beat in Dutch does not consistently take on the function of a border signal before the vowel in the initial sound of stressed syllables, but is used as a means of emphasis . Example: ndl. : Dat doe ik [ dɑ‿duʷək ] - German : I'll do that [ the maxə ʔɪç ]

The Dutch accent in other languages

Dutch phonology also influences the Dutch accent in other languages.

In German

In the Netherlands and Flanders, German strongly influenced by Dutch is also jokingly called “steenkolenduits” (coal German), analogous to the term “steenkolenengels” (coal English), which is the jumble of Dutch and English words, syntax and proverbs for communication between Dutch dock workers with the British crews of the coal boats around 1900.

In a study from 2009, German native speakers were asked which foreign accents they found sympathetic or unsympathetic. In this survey, 7% of those questioned rated the Dutch accent as particularly likeable. In general, the Dutch accent came out of the poll as fairly neutral. The study showed, however, regional differences in the assessment of the Dutch accent, so it is more popular in northern Germany than in southern Germany.

Typical features of the Dutch accent in German include: a .:

| Standard German | Dutch accent | example | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| [ɡ] [eːjɛ] |

[ɣ] [eː] |

[ɣeːjɛn] instead of [ɡeːn̩] (to go) | The elongation h is often realized as [j] or [h]. |

| [ts] | [z] | [zaɪt] instead of [tsaɪt] (time) | |

| [uːə] | [uːʋə] | [ʃuːʋə] instead of [ʃuːə] (shoes) |

Since in Dutch derived adjectives are usually stressed directly before the suffix and in compound adjectives the second component often has the accent, the accentuation of German adjectives is a persistent source of error for Dutch people.

grammar

Language example

Universal Declaration of Human Rights , Article 1:

- All canteens were born vrij en gelijk in waardigheid en rights. Zij zijn begiftigd met understanding en weten, en behoren zich every elkander in een geest van broederschap te.

- All people are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should meet one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

literature

- Eelco Verwijs, J. Verdam : Middelnederlandsch woordenboeck. I-XI, 's-Gravenhage (1882) 1885-1941 (1952); Reprint there 1969–1971.

- Willy Vandeweghe: Grammatica van de Nederlandse zin. Garant, Apeldoorn 2013, ISBN 978-90-441-3054-6 .

Web links

- Online dictionary Uitmuntend - German-Dutch dictionary with over 400,000 headwords

- An evolving online dictionary - a dictionary with sample texts from the Free University of Berlin

- Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren - high-quality scientific and literary texts for free download

- Online language course ( Memento from February 7, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) - Online language course of the University of Vienna with sound output ( RealPlayer required)

- Dutch learning system (in German)

- Dutch for travelers - pronunciation, words and phrases, grammar, and relevant links. In English

- Dutch online library - Large selection of Dutch literature from all centuries, as well as academic and dictionaries

- Dutch Language Institute - Dutch Language Institute (in Dutch)

- Monolingual dictionary - collection of Dutch vocabulary with phrases, synonyms and paraphrases in the Dutch language.

- Neon - Neon is a project of the Dutch Studies of the Free University of Berlin with lots of information about the Dutch language

- Fachvereinigung Dutch - The German-speaking association of Dutch teachers and lecturers at general education schools, adult education centers, technical colleges and universities.

- Differentiation between the terms Dutch, Dutch and Flemish .

- E-ANS: de electronic ANS : electronic version of the second, revised edition of the Algemene Nederlandse Spraakkunst (ANS) from 1997, a comprehensive grammar in Dutch.

- All literary translators into German at the Nederlands Letterenfonds (optionally in English, Dutch)

- buurtaal.de private website

Individual evidence

- ↑ Taalunieversum.org, facts and figures. Retrieved April 13, 2020 .

- ^ Taalunieversum.org, Sprachraum und Landsprache. Retrieved April 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Summary of the 2011 census (PDF), accessed on December 14, 2015

- ↑ Mackensen, Lutz (2014): Origin of words: The etymological dictionary of the German language, Bassermann Verlag, p. 102.

- ↑ Polenz, Peter (2020): History of the German Language, Walter de Gruyter GmbH, pp. 36–7.

- ^ J. De Vries : Nederlands Etymologische Woordenboek. Brill, 1987, p. 143.

- ↑ M. Philippa et al .: Etymologically Woordenboek van het Nederlands [Duits]. 2003-2009.

- ^ L. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period. 2002, pp. 101-103.

- ↑ M. Philippa et al .: Etymologically Woordenboek van het Nederlands [Duits]. 2003-2009.

- ^ L. Weisgerber: German as a popular name. 1953.

- ^ L. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period. 2002, pp. 98-110.

- ↑ FA Stoett: Nederlandse spreekwoorden, spreekwijzen, uitdrukkingen en gezegden. Thieme & Cie, Zutphen 1923–2013. P. 422.

- ^ A. Duke: Dissident Identities in the Early Modern Low Countries. 2016.

- ^ L. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period (2002), p. 102.

- ^ FW Panzer: Nibelung problematics: Siegfried and Xanten, 1954, p.9.

- ^ M. de Vries & LA te Winkel: Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal , the Hague, Nijhoff, 1864-2001.

- ^ M. Janssen: Atlas van de Nederlandse taal: Editie Vlaanderen, Lannoo Meulenhoff, 2018, p.29.

- ^ GAR de Smet, The names of the Dutch language in the course of its history; in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 37 (1973), p. 315-327

- ^ GAR de Smet, The names of the Dutch language in the course of its history; in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 37 (1973), p. 315-327

- ↑ Based on the data in M. Janssen: Atlas van de Nederlandse taal , Editie Vlaanderen, Lannoo Meulenhoff, 2018, p. 29. and W. de Vreese: Over de benaming onzer taal inzonderheid over “Nederlandsch” , 1910, p. 16 -27. and GAR de Smet: The designations of the Dutch language in the course of its history in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 37 (1973), pp. 315–327.

- ↑ LH Spiegel: Twe-spraack vande Nederduitsche letterkunst (1584)

- ^ L. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period (2002), p. 102-103

- ↑ M. Philippa, F. Debrabandere, A. Quak, T. Schoonheim and N. van der Sijs. Etymologically Woordenboek van het Nederlands. Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal, Leiden, 2003–2009.

- ^ L. De Grauwe: Emerging Mother-Tongue Awareness: The special case of Dutch and German in the Middle Ages and the early Modern Period (2002), p. 102.

- ↑ W. de Vreese: Over de benaming onzer taal inzonderheid over “Nederlandsch” , 1910, p. 16-27.

- ↑ M. Philippa ea (2003–2009) Etymologically Woordenboek van het Nederlands [Duits] .

- ↑ M. Janssen: Atlas van de Nederlandse taal , Editie Vlaanderen, Lannoo Meulenhoff, 2018, p. 82.

- ↑ Willy Pijnenburg, Arend Quak, Tanneke Schoonheim: Quod Vulgo Dicitur, Rudopi, 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Werner Besch, Anne Betten, Oskar Reichmann , Stefan Sonderegger: History of language. 2nd subband. Walter de Gruyter, 2008, p. 1042.

- ↑ See Herman Vekeman, Andreas Ecke: History of the Dutch language . Lang, Bern [u. a.] 1993. (German textbook collection; 83), pp. 27–28.

- ↑ See Herman Vekeman, Andreas Ecke: History of the Dutch language . Lang, Bern [u. a.] 1993. (German textbook collection; 83), pp. 27-40.

- ↑ A simplified representation that traces Dutch as a whole back to Lower Franconian can be found e.g. B. in the family tree of the Germanic languages on the TITUS site .

- ↑ Werner König : dtv atlas on the German language. ISBN 3-423-03025-9 , p. 53.

- ^ N. Niemeyer: Contributions to the history of the German language and literature, Volumes 87-88, 1965, p. 245.

- ^ Stefan Sonderegger: Stefan Sonderegger : Basics of German language history. Diachrony of the language system. Volume 1: Introduction, Genealogy, Constants. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1979 (reprint 2011), pp. 118–128.

- ^ Guy Janssens: Het Nederlands vroeger en nu . ACCO, Antwerp 2005, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Van Bezooijen, R. & Gooskens, C. (2005). How easy is it for speakers of Dutch to understand spoken and written Frisian and Afrikaans, and why? In J. Doetjes & J. van de Weijer (eds). Linguistics in the Netherlands, 22, 13-24.

- ↑ Gooskens et al., Cross-Border Intelligibility on the Intelligibility of Low German among Speakers of Danish and Dutch .

- ^ Charles Boberg, The Handbook of Dialectology: dialect Intelligibility. John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

- ↑ Vincent J. van Heuven: Mutual intelligibility of Dutch-German cognates by humans and computers . November 12, 2010.

- ^ Intelligibility of standard German and low German to speakers of Dutch. C. Gooskens 2011. (English)

- ↑ HWJ Vekeman, Andreas corner, P. Lang: History of the Dutch language, 1992, p. 8

- ↑ Heinz Eickmans, Jan Goossens, Loek Geeraedts, Robert Peters, Jan Goossens, Heinz Eickmans, Loek Geeraedts, Robert Peters: Selected writings on Dutch and German linguistics and literary studies, Waxmann Verlag, Volume 22, 2001, p. 352.

- ↑ Heinz Eickmans, Jan Goossens, Loek Geeraedts, Robert Peters, Jan Goossens, Heinz Eickmans, Loek Geeraedts, Robert Peters: Selected writings on Dutch and German linguistics and literary studies, Waxmann Verlag, Volume 22, 2001, p. 349.

- ↑ Heinz Eickmans, Jan Goossens, Loek Geeraedts, Robert Peters, Jan Goossens, Heinz Eickmans, Loek Geeraedts, Robert Peters: Selected writings on Dutch and German linguistics and literary studies, Waxmann Verlag, Volume 22, 2001, p. 353.

- ^ Map based on: Meineke, Eckhard and Schwerdt, Judith, Introduction to Old High German, Paderborn / Zurich 2001, p. 209.

- ^ J. Van Loon: Een Laatoudnederlands sjibbolet. Taal en Tongval, Historische Dialectgeografie (1995) p. 2.

- ^ J. Van Loon: Een Laatoudnederlands sjibbolet. Taal en Tongval, Historische Dialectgeografie (1995) p. 2.

- ^ M. De Vaan: The Dawn of Dutch: Language contact in the Western Low Countries before 1200. John Benjamin Publishing Company, 2017, pp. 12-13.

- ^ M. De Vaan: The Dawn of Dutch: Language contact in the Western Low Countries before 1200. John Benjamin Publishing Company, 2017, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Marijke Mooijaart, Marijke van der Wal: Nederlands van Middeleeuwen dead Gouden Eeuw. Cursus Middelnederlands en Vroegnieuwnederlands. Vantilt, Nijmegen, 2008, p. 7.

- ↑ a b A. Quak, JM van der Horst, Inleiding Oudnederlands , Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-5867-207-7

- ↑ Luc de Grauwe: Amsterdam Contributions to Older German Studies, Volume 57: West Frankish: bestaat dat? Over Westfrankisch en Oudnederlands in het oud-theodiske variëteitencontinuüm, 2003, pp. 94–95

- ^ Alfred Klepsch: Der Name Franken In: Franconian Dictionary (WBF) , Bavarian Academy of Sciences, accessed on July 31, 2020.

- ↑ Janssens, Guy (2005): Het Nederlands vroeger en nu, ACCO, pp. 56-57.

- ↑ CGN de Vooys: Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse taal, Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen (1970), p. 26.

- ↑ Gysseling, Maurits, Studia Germanica Gandensia 6: Proeve van een Oudnederlandse grammatica, 1964, pp. 9-43.

- ↑ J. Verdam & FA Stoett: Uit de geschiedenis der Nederlandsche taal, Uitgeverij Thieme, Nijmegen (1923), p. 54.

- ^ Map based on: W. Blockmans, W. Prevenier: The Promised Lands: The Countries under Burgundian Rule, 1369–1530. Philadelphia 1999 and Guy Janssens: Het Nederlands vroeger en nu. ACCO, Antwerp, 2005.

- ^ A. van Santen: Morfologie: de woordstructuur van het Nederlands , Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

- ^ Herman Vekeman and Andreas Ecke, History of the Dutch Language , Bern 1993, ISBN 3-906750-37-X

- ↑ KH Heeroma: Aan weer van de grens edges : in Neerlandia. Year 64, Algemeen Nederlands Verbond, The Hague, 1960.

- ↑ R. Belemans: Belgian Limburg: Volume 1 van Taal in stad en land , Tielt, Lannoo Uitgeverij, 2004, pp 22-26.

- ^ Norman Devies: Vanished Realms, The History of Forgotten Europe. Darmstadt 2013, ISBN 978-3-534-25975-5 , p. 155 (an excerpt from W. Blockmans, W. Prevenier: The Promised Lands: The Countries under Burgundian Rule, 1369–1530. Philadelphia 1999, p. 164 f.).

- ^ R. Boumans, J. Craeybeckx: Het bevolkingscijfer van Antwerpen in het derde kwart der XVIe eeuw . TG, 1947, pp. 394-405.

- ^ David Nicholas: The Domestic Life of a Medieval City: Women, Children and the Family in Fourteenth Century Ghent. P. 1.

- ^ Hendrik Spruyt: The Sovereign State and Its Competitors: An Analysis of Systems Change . Princeton University Press, 1996.

- ^ Larkin Dunton: The World and Its People . Silver, Burdett, 1896, p. 160.

- ↑ Guido Geerts, Voorlopers en varianten van het Nederlands , 4de druk, Leuven 1979

- ↑ M. Janssen: Atlas van de Nederlandse taal, Editie Vlaanderen, Lannoo Meulenhoff, 2018, p. 47.

- ↑ Nicoline van der Sijs: Calendarium van de Nederlandse Taal: De geschiedenis van het Nederlands in jaartallen, Sdu, 2006, p. 141.

- ↑ Nele Bemong: Naties in een spanningsveld: tegenstrijdige bewegingen in de identiteitsvorming in negentiende-eeuws Vlaanderen en Nederland, Uitgeverij Lost, 2010, pp 88-90.

- ↑ Carter, Ronald P .: "Standard grammars, spoken grammars: some educational implications." (2002).

- ^ Gert De Sutter: De vele gezichten van het Nederlands in Vlaanderen. Een inleiding tot de variatietaalkunde, 2017.

- ↑ Kollewijn, RA: 'Onze lastige spelling. Een voorstel tot vereenvoudiging ', Varsh van den dag, jrg. 6, (1891), pp. 577-596.

- ↑ J. Noordegraaf: Van Kaapsch-Hollandsch naar Afrikaans, Visies op verandering, 2004, p. 22.

- ↑ Van Eeden, P. (1995) Afrikaans hoort by Nederlands, ons Afrikaanse taalverdriet , p. 17.

- ↑ General Administrative Law Act (AWB) of the Netherlands.

- ^ Niklaas Johannes Fredericks: Challenges facing the development of Namibian Languages. Conference "Harmonization of Southern African languages", without location, 2007, p. 1.

- ↑ Van Eeden, P. (1995) Afrikaans hoort by Nederlands, ons Afrikaanse taalverdriet , p. 17.

- ^ Niklaas Johannes Fredericks: Challenges facing the development of Namibian Languages. Conference "Harmonization of Southern African languages", without location, 2007, p. 2.

- ↑ Marita Mathijsen: Boeken onder druk: censuur en pers-onvrijheid in Nederland sinds de boekdrukkunst, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2001, ISBN 978-90-8964-306-3 .

- ↑ GR Jones: Tussen onderdanen, rijksgenoten en Nederlanders. Nederlandse politici over burgers uit Oost en West en Nederland 1945-2005, Rozenberg Publishers, Amsterdam, 9789051707793

- ↑ Jan Goossens (1973): Low German Language - Attempt at a Definition . In: Jan Goossens (Ed.): Low German - Language and Literature . Karl Wachholtz, Neumünster, pp. 9-27.

- ^ Werner Besch: Sprachgeschichte: a manual for the history of the German language, 3rd part. De Gruyter, 2003, p. 2636.

- ↑ Georg Cornelissen: The Dutch in the Prussian Gelderland and its replacement by the German, Rohrscheid, 1986, p. 93.

- ^ Society for the German Language. In: Der Sprachdienst, No. 18: Die Gesellschaft, 1974, p. 132.

- ↑ Foreign-language minorities in the German Empire . Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ Herman Vekeman, Andreas corner: History of the Dutch language . Lang, Bern [u. a.] 1993, pp. 213-214.

- ^ H. Niebaum: Introduction to Dialectology of German. 2011, p. 98.

- ^ J. Jacobs: The Worlds of the Seventeenth-Century Hudson Valley, SUNY Press, 2014, p. 158.

- ↑ Van der Sijs, N. (2009): Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages, Amsterdam University Press, p 34th

- ↑ Van der Sijs, N. (2009): Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages, Amsterdam University Press, p. 51

- ↑ Ted Widmer: Martin Van Buren. P. 6.

- ↑ United States Census 2000 , accessed April 27, 2020.

- ↑ 2006 Canadian Census , accessed April 27, 2020.

- ^ C. Holt: Culture and Politics in Indonesia, Equinox Publishing, 2007, p. 287.

- ^ Daniel S. Lev: Legal Evolution and Political Authority in Indonesia: Selected Essays, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2000, pp. 163–168.

- ↑ Guy Janssens: Geschiedenis van het onderwijs van het Nederlands in Wallonië (PDF), in: Over taal , 2007, No. 4, pp. 87-89

- ↑ Jonathan Van Parys en Sven Wauters, Les Connaissances linguistiques en Belgique , CEREC Working Papers, 2006, No. 7, p. 3

- ^ [1] Education portal NRW

- ↑ Gazet van Antwerpen: Elke dag verschijnen er 57 nieuwe boeken in het Nederlands, 2016. In: Het Laatste Nieuws, October 29, 2016, accessed on April 18, 2020.

- ↑ B. Schrijen: Bioscoopgeschiedenis in cijfers (1946-2017) , 2018. In: Boekmanstichting, accessed on April 18.

- ↑ J. Daan, 1969, Van Randstad tot Landrand. Bijdragen en Mededelingen of the Dialect Commissie van de KNAW XXXVI. Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche Uitgevers Maatschappij, 54 pagina's met kaart en grammofoonplaat.

- ↑ Heeringa, WJ (2004). Measuring Dialect Pronunciation Differences using Levenshtein Distance. Groningen: sn

- ↑ J. Hoppenbrouwers: De indeling van de Nederlandse streektalen: dialects van 156 steden en dorpen geklasseerd volgens de FFM, Uitgeverij Van Gorcum, 2001, pp. 48-50.

- ↑ H. Entjes: dialects in Nederland. Knoop & Niemeijer, 1974, p. 131

- ↑ Jan Goossens: Dutch dialects - seen from the German. In: Low German word. Small contributions to the Low German dialect and name. Volume 10, Verlag Aschendorf, Münster 1970, p. 61.

- ↑ What is the greatest woordenboek ter wereld? In: Taaluniversum, 2005, accessed on April 29, 2020. <! - The outdated source claims that the Woordenboek of the Nederlandsche Taal is the largest dictionary in the world. That is now obsolete and several other dictionaries are now larger. See the easy-to-use en: List of dictionaries by number of words on Wikipedia. ->

- ↑ Hoeveel woorden kent het Nederlands? In: Taaluniversum, 2020, accessed April 29, 2020.

- ↑ Brandt Cortius, Hugo: Vrijdag? Dit moet cultuur zijn! Singel Uitgeverijen, 2013.

- ↑ Van der Sijs, Nicoline (1998): Geleend en uitgeleend Nederlandse woorden in other talen & Andersom, Uitgeverij Contact Amsterdam / Antwerp, S. 175th

- ↑ Van der Sijs, Nicoline (1998): Geleend en uitgeleend: Nederlandse woorden in other talen & andersom, Uitgeverij Contact Amsterdam / Antwerpen, pp. 171–175.

- ↑ Applebaum, Wilbur (2003): Encyclopedia of the Scientific Revolution: From Copernicus to Newton, Routledge.

- ↑ Bakker, Martijn (1994): Nederlandstalige wiskundige terminologie van Simon Stevin Het Nederlands as ideal taal in de wetenschap, in: Neerlandia, year 98, p. 130.

- ↑ Bloemendal, Jan (2015): Bilingual Europe: Latin and Vernacular Cultures - Examples of Bilingualism and Multilingualism c. 1300-1800, BRILL, p. 158.

- ↑ Nicoline van der Sijs: wereldwijd woorden Nederlandse. Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag, 2010, pp. 135ff.

- ↑ Otto, Kristin: Eurodeutsch - Investigations on Europeanisms and Internationalisms in German Vocabulary: a work from the perspective of Eurolinguistics using the example of newspapers from Germany, Austria, Switzerland and South Tyrol, Logos Verlag Berlin, 2009, p. 153.

- ↑ Van der Sijs, Nicoline (1998): Geleend en uitgeleend: Nederlandse woorden in other talen & andersom, Uitgeverij Contact Amsterdam / Antwerpen, p. 24.

- ^ Kluge, Friedrich (1911): Seemannsprache. Verbatim history handbook of German boatman expressions of older and more recent times. Halle: Publishing house of the bookstore of the orphanage.

- ^ Sperber, Hans : History of the German Language, Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2019, p. 44.

- ^ W. Foerste: The influence of Dutch on the vocabulary of the younger Low German dialects in East Friesland, Schuster Verlag, 1975.

- ↑ Van der Sijs, N. (2009): Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops: The Influence of Dutch on the North American Languages, Amsterdam University Press.

- ↑ De Haan, GJ (2011) Het Fries en zijn verhouding met het Nederlands, in: Wat iedereen van het Nederlands moet weten en waarom, Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, Amsterdam, pp. 246-250.

- ^ H. Cox: Van Dale Groot spreekwoordenboek, Van Dale, Utrecht, 2009.

- ↑ S. Prędota: On German Equivalents of Dutch Priamels, in: Styles of Communication, 3, 2011.

- ^ F. Boers: Applied linguistic perspectives on cross-cultural variation in conceptual methaphors , in: Metaphor and Symbol 19, 2003, pp. 231-238.

- ^ S. Nacey: Metaphor Identification in Multiple Languages: MIPVU around the world , John Benjamin Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 2019.

- ↑ Johan Huizinga: Herfsttij the Middeleeuwen : Study over levens- s thought vormen the veertiende en vijftiende eeuw in Frankrijk en de Nederlanden . Leiden University Press, 2018, pp. 300–328.

- ↑ U. Grafberger: Holland for the trouser pocket: What travel guides conceal , S. Fischer Verlag, 2016.