Norwegian language

| Norwegian (norsk) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Norway | |

| speaker | Mother tongue: approx. 4.3 million | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

no |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

nor |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

nor |

|

The Norwegian language (own name Norsk [ nɔʃk ]), which includes the two standard varieties Bokmål [ ˈbuːkmɔːl ] and Nynorsk [ ˈnyːnɔʃk ] or [ ˈnyːnɔʀsk ], belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages . Norwegian is spoken as the mother tongue of around five million Norwegians , the majority of whom live in Norway , where it is the official language . It is also the working and lingua franca in the Nordic Council . Over time, Norwegian has been standardized into four varieties , two of which are now officially recognized:

Bokmål (German"book language"), until 1929Riksmål:

- official standard variety

- is mainly based on Danish and (to a lesser extent) on certain urban Norwegian dialects

Riksmål [ ˈrɪksmɔːl ] ( Eng . "Reich language") intoday's senseis a variant of Bokmål:

- without official status

- conservative variety , which for historical reasons is even more Danish-oriented than Bokmål

Nynorsk (Eng. "New Norwegian"), until 1929Landsmål:

- official standard variety

- is mainly based on rural Norwegian dialects.

Høgnorsk [ ˈhøːgnɔʃk ] (Eng. "High Norwegian"):

- without official status

- conservative Nynorsk , which is more strongly oriented towards the original Aasen standardization (Landsmål)

Bokmål is written by around 85 to 90 percent of the Norwegian population. These were originally a variety of Danish, the centuries in Norway written language was, but - gradually on the basis of the bourgeois-urban - especially in the first half of the 20th century vernacular was norwegisiert. Bokmål is often divided into moderate and radical Bokmål, with intermediate forms. Moderates Bokmål is the most common variant of Bokmål and largely identical to modern Riksmål.

The Riksmål is an older, now officially disapproved variety, which is similar to a moderate Bokmål . It is committed to the Danish-Norwegian literary tradition and a little less Norwegianized in terms of spelling. Since the 2000s there have been practically no differences between Riksmål and moderate Bokmål.

Nynorsk, on the other hand, is a synthesis of the autochthonous Norwegian dialects . It is written by around 10 to 15 percent of the Norwegian population. The name Nynorsk comes from the language phase to which autochthonous Norwegian dialects belong since the beginning of the 16th century; however, this meaning is often unknown to non-linguists.

Finally, Høgnorsk is only cultivated in very small circles.

The three mainland Scandinavian languages are closely related. With a little practice, Norwegians , Danes and Swedes often understand the language of their neighbors. However, a distinction must be made between the relationship with regard to the written language and pronunciation. In particular, the Danish and Norwegian (in the “Bokmål” variant) written languages differ only insignificantly, while that of Swedish differs more from the other two. The pronunciations of many Norwegian and Swedish dialects are often similar and form a cross-border dialect continuum. The Danish pronunciation, on the other hand, differs considerably from the pronunciations of the other two languages, which makes oral communication with speakers of Norwegian or, in particular, Swedish difficult. Overall, Norwegian occupies a certain “middle position” among the three languages, which makes communication with the two neighboring languages easier. Norwegian speakers - especially Nynorsk users - are also better placed to learn Faroese and Icelandic , as these languages have their origins in the dialects of Western Norway.

history

The origin of the Norwegian language lies in Old Norse , which was called Norrønt mál (Nordic language) by Norwegians and Icelanders . In contrast to most of the other middle and larger languages in Europe, however, the old Norwegian script varieties have not been able to develop into a uniformly standardized standard over the centuries. The reasons are firstly the particular impassability of Norway and the consequent poor traffic routes, which promoted a comparatively uninfluenced and independent development of the dialects, secondly the long lack of an undisputed political and economic center and thirdly the Danish language that lasted from the late Middle Ages to the early 19th century Dominance that made Danish the official language in Norway.

In the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, Norwegian was heavily influenced by Low German and Danish. In the Hanseatic period was Middle Low German , the lingua franca of the North. Many Low German words were integrated as loan words . From 1380 to 1814 Norway was united with Denmark, initially as a Danish-Norwegian personal union , later as a real union . During this time, the old Norwegian written language became increasingly out of use and disappeared completely in the course of the Reformation .

The original dialects were still spoken in the country. After Norway separated from Denmark in 1814, as in other young European countries, a national romantic wave emerged in the course of the 19th century, which mainly sought to tie in with the Norwegian past of the Middle Ages (i.e. the time before the unification with Denmark) . This also applied to the language: the supporters of this movement demanded that the original Norwegian language of the Middle Ages should be brought back to life in order to set an example for the emancipation of Norway. A linguistic debate arose over the question of whether one should continue to approve of Danish influences in Norwegian ( Welhaven , Anton Martin Schweigaard ) or whether one should create an independent language based on traditional Norwegian dialects ( Wergeland , P. A. Munch , Rudolf Keyser ). While Wergeland and his followers ignored the past 400 years of Danish influence and wanted to give the medieval Norwegian a boost, Schweigaard pointed out in the newspaper Vidar in 1832 that one could not simply overlook several centuries of cultural exchange; it is impossible to outsource what has once been assimilated.

Finally, in the 1850s, the poet and linguist Ivar Aasen developed the Landsmål , which has been officially called Nynorsk since 1929 . The aim was expressly to give the - dialect-speaking - people their own written language, which was to appear alongside the Danish written language of the bourgeois-urban upper class; Nynorsk thus became a central element of the democracy movement. Landsmål / Nynorsk has been an officially recognized written language since 1885 . The basis for this new language was not a single dialect, but a common system that Aasen had found through scientific research into a large number of dialects from all parts of the country. In the course of the 20th century, Nynorsk , which had previously been dominated by western and central Norwegian, was increasingly brought closer to the eastern Norwegian dialects on the one hand and the south-eastern Norwegian Bokmål as part of several reforms that pushed back the central Norwegian elements . Nynorsk differs from a planned language in that it is anchored in closely related, living dialects.

At the same time, the grammar school teacher Knud Knudsen advocated a radical language reform based on what he assumed was a "colloquial language of the educated". His reform proposals were largely adopted by Parliament in the spelling reform of 1862 and formed the basis of the Riksmål, which was renamed Bokmål by Parliament in 1929 and later split up into Bokmål and Riksmål , each with their own norms and traditions, due to controversies about standardization .

Due to the increased national awareness , Nynorsk was able to win more and more followers until 1944 and at that time had almost a third of the Norwegians on its side. In the meantime, their share of the population has decreased to around 10–15 percent. There are several reasons for this: In urban areas, especially in the Oslo region , Nynorsk is perceived as alien. The urban bourgeoisie has always rejected Nynorsk , which is based on rural dialects . As a result, the Nynorsk still lacks any real anchoring in the economic and political centers. On the other hand, some rural residents, especially in Eastern Norway, perceive Nynorsk to be artificial, as it seems like a dialect patchwork; and finally, the grammar of Nynorsk is more difficult than that of Bokmål, although it must be admitted that most Norwegian dialects are nevertheless closer to Nynorsk than to Bokmål , which in turn has some phonological , morphological and other grammatical features quite alien to autochthonous Norwegian .

In the course of the 20th century, several spelling reforms were carried out with the attempt to bring the two written languages closer together (long-term goal: Samnorsk “Common Norwegian, Unified Norwegian”). In the reform of 1917, under pressure from the Nynorsk movement, a number of specifically “Norwegian” expressions were propagated to replace traditional Danish terms. Since this did not happen to the extent expected, another reform was passed in 1938: numerous traditional Danish elements were no longer allowed to be used. But this language was hardly accepted. There were big disputes, for example parents corrected their children's school books because the conflict was and is still very emotional. At the same time, Nynorsk was increasingly opened to younger forms in terms of linguistic history. Further reforms took place in 1959, 1981 (Bokmål), 2005 (Bokmål) and 2012 (Nynorsk), whereby those of 2005 in Bokmål again allowed a number of traditional Danish forms. The result of all of these reforms is the existence of “moderate” and “radical” forms in the spelling norm from which to choose. The complicated system of official main and subsidiary forms was abandoned in Bokmål 2005, in Nynorsk 2012. The long-term goal of a Samnorsk was expressly dropped at the same time.

Legal conditions and distribution of language forms

The two language forms Bokmål and Nynorsk are officially recognized by the state . According to the Language Act, no state authority is allowed to use one of the two more than 75%, which in practice, however , is often not followed - to the disadvantage of Nynorsk . State and county authorities must answer queries in the same language in which they are made. At the municipal level, the authority may reply in the language that it has declared to be official for its territory. Both variants are taught in school, with the one that is not the main variant being called sidemål ( secondary language).

Nynorsk is the official language of 25% of the municipalities, in which a total of 12% of the total population live, Bokmål is the official language in 33% of the municipalities, the remaining 42% of the municipalities are "language-neutral" (which in fact is mostly equivalent to the use of Bokmål ). At school and parish level, official use of Nynorsk extends beyond this area; at primary school level, for example, 15% of all pupils have Nynorsk as their school language, and in 31% of the parishes liturgy and sermons are in Nynorsk .

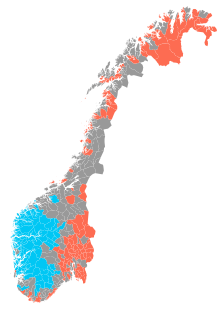

From a geographical point of view, Nynorsk is the official form of language in most of the municipalities of fjord-rich Western Norway (excluding the towns and municipalities close to the city) and in the geographically adjacent central mountain valleys of Eastern Norway ( Hallingdal , Valdres , Gudbrandsdal ) and southern Norway ( Setesdal , Vest- Telemark ). Bokmål, on the other hand, is the official form of language in most of the municipalities in south-eastern Norway and on the south coast on the one hand, and in some municipalities in northern Norway on the other. At the regional level, Nynorsk is the official language of two Fylker, namely Vestland and Møre og Romsdal , while the other Fylker are "language neutral". Of these language-neutral Fylker, Agder with 24%, Vestfold and Telemark with 35% and Rogaland with 39% have a relatively large share of Nynorsk communities.

| Fylke | Total number of municipalities |

Bokmål | Nynorsk | neutral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agder | 25th | 7th | 6th | 12 |

| Domestic | 46 | 22nd | 7th | 17th |

| Møre and Romsdal | 26th | - | 16 | 10 |

| North country | 41 | 20th | - | 21st |

| Oslo | 1 | - | - | 1 |

| Rogaland | 23 | 2 | 9 | 12 |

| Troms and Finnmark | 39 | 21st | - | 18th |

| Trøndelag | 38 | 7th | - | 31 |

| Vestfold and Telemark | 23 | 4th | 8th | 11 |

| Vestland | 43 | - | 41 | 2 |

| Viken | 51 | 35 | 3 | 13 |

| total | 356 | 118 | 90 | 148 |

The language agreement in the Nordic Council also guarantees that Danish and Swedish are allowed in official correspondence. This applies to both sides.

Modern Norwegian

Bokmål and Nynorsk

Examples of differences between Bokmål, Nynorsk and other North Germanic languages:

| Bokmål Danish |

Jeg kommer from Norge. | [ jæɪ kɔmːər fra nɔrgə ] [ jɑɪ (jə) kɔmɔ fʁa nɔʁɣə ] |

| Nynorsk | Eg kjem frå Noreg. | [ eːg çɛm fro noːrɛg ] |

| Icelandic | Ég kem frá Noregi. | [ jɛːɣ cɛːm womanː noːrɛːjɪ ] |

| Swedish | Jag kommer från Norge. | [ jɑː (g) kɔmər froːn nɔrjə ] |

| "I'm from norway." |

| Bokmål | Hva heter you? | [ va heːtər dʉ ] |

| Danish | Hvad hedder you? | [ væ hɛðɔ you ] |

| Nynorsk | Kva happy you? | [ kva hæɪtər dʉ ] |

| Icelandic | Hvað heitir þú? | [ kvað heitɪr θuː ] |

| Swedish | Vad heter you? | [ vɑ heː ɛ tər dʉ ] |

| "What's your name?" (Literally: "What do you mean?") |

Riksmål

Opponents of the language reforms that were supposed to bring Bokmål closer to Nynorsk continue to use the name Riksmål for the language form they cultivated . Typical for this is the use of some Danish numerals, word forms such as efter instead of etter or sne instead of snø , the avoidance of the feminine gender (e.g. boken instead of boka , "the book") and the avoidance of diphthongs (e.g. sten instead of stone , "stone"). In fact, on the one hand, due to the re-approval of many Dano-Norwegian forms in Bokmål , and on the other hand, due to the inclusion of numerous elements from Bokmål in Riksmål, these two variants have come closer together in the last thirty years.

Høgnorsk

The so-called Høgnorsk (roughly “High Norwegian”) is an unofficial variant of Nynorsk, a language form that is very similar to the original Landsmål by Ivar Aasen . The Høgnorsk movement disregards the Nynorsk reforms after 1917.

This form of language is only used in writing by a very small group of Norwegians, but elements of High Norwegian are still used in many. The spelling often seems archaic to the majority of Norwegians, but when it comes to speaking, the language can hardly be distinguished from traditional dialects and the normal language built on them. Only native words are used more than Low German loanwords in High Norwegian. Since it was written before 1917, a large part of the Norwegian song treasure is, from today's perspective, written in High Norwegian.

Riksmål, Bokmål, Nynorsk and Høgnorsk in comparison

| Riksmål, Bokmål, Danish | Dette he en hest. |

| Nynorsk, Høgnorsk: | Dette he a hest. |

| Swedish | Detta you have. (other spelling) |

| Icelandic | Þetta he hestur. (without indefinite article ) |

| "This is a horse." |

| Riksmål, Danish | Regnbuen har mange farver. |

| Bokmål | Regnbuen har mange farger. |

| Nynorsk | Rainbow harbors much fargar. |

| Høgnorsk | Rainbow hev mange fargar. |

| Swedish | Regnbågen has många färger. |

| "The rainbow has many colors." |

Phonology (phonology)

alphabet

An alphabet of 29 letters is used to write the Norwegian language: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S , T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z, Æ, Ø, Å.

General pronunciation rules

Bokmål and Nynorsk are written languages, the pronunciation is not actually fixed, because the dialects are mainly spoken. The pronunciation details vary depending on the grammar. Some written sounds can be omitted in the pronunciation. In particular, the final t in the specific article (det / -et) and the "g" of the final syllable -ig are generally not pronounced.

Pronunciation of vowels

The ö-sound in Norwegian has the letter Ø ø , the ä-sound has Æ æ , the o-sound often has Å å , while the letter o often represents the u-sound: bo [ buː ] "living", dør [ døːr ] "door", ærlig [ æːrli ] "honestly". Norwegian and is usually [ ʉ ] , before a Nasalverbindung but [ u ] spoken. Unstressed e is short in language ( [ ə ] ). y is an above -According [ y ] .

Pronunciation of consonants

Most Norwegian dialects have a rolled “r” similar to Italian or Southeast German (Vorderzungen-R), but some western dialects also have German or Danish “r” (suppository-R). The r-sound must not be swallowed (ie dager [ daːgər ], and not [ daːgɐ ]).

The Norwegian s is always voiceless (like a sharp S in the outside ), the Norwegian v (and also the letter combination hv ) is spoken as in “Vase” (not as in Vogel !).

The following sound combinations to consider: sj, skj "sh" are spoken: nasjon [ naʃuːn ] "nation," gj, hj, lj "j" are spoken, tj is pronounced like in "tja" kj is the I -According [ ç ] : kjøre [ çøːrə ] "drive", rs is spoken in some dialects "sh": vær så god! So “here you go!” Is [ værsɔgu: ] or [ væʃɔgu: ].

Before clear vowels (i, y, egg, øy) Special rules apply: sk "sh", is here g is "j" and here k is here "ch" [ ç ] spoken: ski [ ʃiː ] gi [ jiː ] "to give", kirke [ çɪrkə ] "church".

The letters c, q, w, x, z only appear in a few foreign words. Instead of ck one writes kk , kv stands for qu , f / t / k stands for ph / th / kh , z (in German) is usually replaced by s : sentrum / senter corresponds to "center", sukker corresponds to "sugar" .

Exceptions and Variants

Consider are mainly the following exceptions (Bokmål): det [ de ] "that it, that" -et [ ə ] "the" de [ DI ] "She Who (plural)" above [ o ] "and" jeg / meg / deg / seg [ jäi Maei Daei Saei ] "I / me / you / herself".

Depending on the speaker, a long a tends to have an o-like sound like call in English , while æ goes in the direction of “a” as in “father” and y can hardly be distinguished from our “i”. Depending on the dialect, the diphthong ei is pronounced like [ æj ] or [ aj ].

Overview of the sounds of Norwegian

Vowels

Norwegian has 19 monophthongs and seven diphthongs .

| front | central | back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | |

| closed | iː | i | yː | y | ʉː | ʉ | uː | u |

| medium | eː | e | O | O | oː / ɔː | ɔ | ||

| open | æː | æ | ɑː | ɑ | ||||

The diphthongs of Norwegian are / æi øy æʉ ɑi ɔy ʉi ui / , each of which is available in a long and a short variant.

Consonants

Norwegian has 23 consonants , including five retroflex sounds, which are to be regarded as allophones . The latter do not occur in the dialects with suppository-R.

| bilabial |

labio- dental |

alveolar |

post- alveolar |

retroflex | palatal | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p b | t d | ʈ ɖ | k g | ||||

| Nasals | m | n | ɳ | ŋ | ||||

| Trills / flaps | r | ɽ | ||||||

| Fricatives | f v | s | ʃ | ç j | H | |||

| Lateral | l | ɭ |

Accent 1 and Accent 2

Norwegian (like Swedish) has two distinct accents, which are often called accent 1 and accent 2 . See: Accents in the Scandinavian languages .

grammar

General preliminary remark: In the following, only those Nynorsk variants are noted that are valid according to the 2012 spelling reform. Rare sounds and forms , which almost only appear in older texts or are used in the circle of Høgnorsk followers, are left out.

Nouns (nouns) and articles (gender words)

Genera (gender)

The Norwegian language officially knows the three genera : masculine, feminine and neuter. Riksmål and conservative Bokmål, like the Danish language, only know the male-female (utrum) and the neuter gender (neuter) . However, the nouns usually give no indication of what gender they are. Often the gender agrees with that of the German noun (e.g. sola "die Sonne", månen "der Mond", barnet "das Kind").

Norwegian also knows the indefinite article, each gender has its own form:

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | German | gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| en dag | a dag | a day | male |

| egg / en bottle | egg bottle | a bottle | Female |

| et hus | eit hus | a house | neutrally |

| et eple | eit eple | An apple | neutrally |

| et øye | eit auga / eye | an eye | neutrally |

As in Danish, in the case of unaccompanied nouns (i.e. if there is no adjective in front of or no personal pronoun after the noun), the definite article is only added as a suffix, by which the gender of the noun can also be recognized:

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | German |

|---|---|---|

| dag en | dag en | the day |

| flask a / flask en | flask a | the bottle |

| hus et | hus et | the house |

| epl et | epl et | the Apple |

| øy et | aug a / aug et | the eye |

With the definite article neuter (-et) the t is not spoken! eple (“apple”) and eplet (“the apple”) are pronounced the same.

In Bokmål, however, female nouns - following Danish tradition - are often treated like masculine:

- ei flaske = en flaske - "a bottle"

- flaska = flasken - "the bottle"

Plural (plural)

In the indefinite plural form, masculine, feminine and (in Bokmål ) polysyllabic neuter nouns end in -er (in Nynorsk there are the endings -ar and -er , comparable to Swedish ), monosyllabic (in Nynorsk also polysyllabic) neuter nouns remain in the Rule endlessly:

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | German |

|---|---|---|

| dager | dagar | "Days" |

| flasker | flasker | "Bottles" |

| hus | hus | "Houses" |

| epler | eple | "Apples" |

| øyne | augo / eye | "Eyes" |

Examples of irregular plural forms are:

- fedre "fathers", mødre "mothers", brødre "brothers", søstre "sisters", døtre "daughters"

- ender "ducks", moving "hands", created "powers", nice "nights", render "edges"

- stender "stalls (classes)", stern "rods", strender "beaches", tenger "pliers", tenner "teeth"

- bøker "books", bønder "farmers", røtter "roots"

- klær "clothes", knær "knee", trær "trees", tær "toes", menn "men", øyne (BM) / augo (NN) "eyes"

All monosyllabic neutrals have no plural ending, e.g. B. hus "house / houses", barn "child / children", but exceptionally also masculine monosyllabic words, e.g. B. sko "Schuh (e)" or neutral polysyllabic words, e.g. B. våpen "weapons".

Around the plurality of specific shapes to be formed, is in Bokmål gender across -ene or -a added (optional for monosyllabic Neutra).

Nynorsk knows -ane, -ene, -o and -a:

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | German |

|---|---|---|

| dagene | dagane | "the days" |

| flaskene | flaskene | "the bottles" |

| husene (less often: husa ) | husa | "the houses" |

| eplene (less often: epla ) | epla | "The apples" |

| øynene (more rarely: øya ) | augo / auga | "The eyes" |

The irregular nouns have here: fedrene "the fathers", ending "the ducks", bøkene "the books" and - with the receipt of the "r" before æ - klærne "the clothes" etc.

Genitive (Wesfall)

In addition to the basic form, the Norwegian noun has its own form for the genitive by adding an -s to the noun (not to articles and pronouns!) In the singular as well as in the plural, regardless of the gender . In the case of multi-part expressions, this genitive rule is applied to the entire expression, i.e. the last word in the expression is given the supplement -s . Ends of the noun or the expression already at a -s , -x or -CH, is used instead of the genitive s only an apostrophe - ' attached:

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | German |

|---|---|---|

| kongens | kongens or til / åt kongen or kongen sin | "of the King" |

| congenes | konganes or til / åt kongane or kongane sin | "Of the kings" |

| men på husets tak | men on huset sitt tak | "The man on the roof of the house" |

| Mars' | til / åt mars or mars sin | "Of March" |

Further examples (Bokmål): Guds ord "God's Word", de gamle mennenes fortellinger "The stories of the old men"

Except for names and people, the genitive is mainly used in the written Bokmål . In written Nynorsk and in the spoken language in general, it is usually paraphrased with the prepositions av, til, på etc. or with a dative construction (“garpegenetiv”, a construction borrowed from Low German), e.g. prisen på boka instead of bokas pris (the price of the book), boka til Olav instead of Olavs bok (Olav's book), taket på huset instead of husets tak (the roof of the house), Stortinget si sak instead of Stortingets sak (the matter of parliament, literally: "Parliament's matter").

In descending order of priority one uses for 'the front door': husdøra, husets dør, døra på huset . The preposition på "auf" is used in this case, because the door is no longer perceived as belonging to the house itself.

Use of the article

No article is attached

- Information on nation, occupation, religion: han er nordmann (BM and NN), han er lutheraner (BM) or han er lutheranar (NN) "he is Norwegian, he is a Protestant"

- following adjectives: første / øverste / neste / siste / forrige / venstre / høyre (BM) or høgre (NN) "first / top / next / last / previous / left / right", e.g. B. neste dag "the next day", på venstre side "on the left side"

- fixed phrases: på kino / sirkus “in the cinema / circus, to the cinema / in the circus”, på skole “to school”, i telt “in a tent”, å skrive brev “write a letter”, å kjøre bil ( BM) or å køyre bil (NN) “drive a car”, spille gitar “play guitar”.

Declination of adjectives (inflection of adjectives)

As in all Germanic languages (with the exception of English), Norwegian distinguishes between strong and weak endings. In both Bokmål and Nynorsk , the plural of all regular adjectives always has the ending -e ; this ending is also used by all changeable weak adjectives for all genders.

Strong adjectives

Masculine and feminine forms have no end in the singular: en gammel (BM) or a gammal (NN) “an old”, ei gammel (BM) or ei gammal (NN) “an old”; the neuter has the ending -t (or -tt ) in the singular : et gammelt (BM) or eit gammalt (NN) "an old", blått lys "blue light". In the plural, the ending -e is almost always used .

| Masculine | en / a stor lastebil | "A big truck" |

| Feminine: | ei stor bru | "A great bridge" |

| Neuter: | et / eit stort hus | "a big house" |

| Plural: | store lastebiler / lastbilar, store bruer, store hus | "Big trucks, bridges, houses" |

- However, many adjectives do not have the ending -t in the neuter: These include adjectives that end in -sk, -ig (BM) or -eg (NN) or consonant + t : et dårlig lag / eit dårleg lag “a bad team ". However, fersk / frisk "fresh" and rask "fast" have the ending -t .

- The adjective is also heavily inflected in the predicative position (while it remains unchanged in German!): Bilen er stor “the car is big”, huset he stort “the house is big”, bilene / bilane er store “the cars are big” , husene / husa er store “the houses are big”.

Weak adjectives

| Masculine | lastebilen the store | "The big truck" |

| Feminine | the store brua | "The great bridge" |

| neuter | det store huset | "The big house" |

| Plural | de store lastebilene, bruene, husene / dei store lastbilane, bruene, husa |

"The big trucks, bridges, houses" |

Adjectives are weakly declined when the noun is defined by the definite article, the demonstrative pronoun denne / dette / disse (dies), a possessive pronoun (mein, dein, sein ...) or a genitive attribute: fars store hus requires a weakly declined Adjective, while it is strongly declined in German: "Father's big house".

- If an adjective comes before a noun, the article must precede the adjective with the / det / de : huset "das Haus"> det store huset "das Großes Haus", accordingly the definiteness of the article is expressed twice, once as det , the other Times as the ending -et .

den / det / de (BM) or den / det / dei (NN) is omitted before hel (BM) / heil (NN) “whole”: hele året / heile året “all year round”.

Irregular adjectives

- In adjectives with unstressed -el / -en / -er (BM) or -al / -en / -ar (NN), the -e- or -a- in front of an ending is usually omitted, and a possibly preceding double consonant is used simplified: gammel / gammal > gamle , kristen > kristne , vakker / vakkar > vakre .

- A number of adjectives are immutable. These include adjectives on vowels (including all comparatives!) And on -s : bra, tro, sjalu, lilla, stille, bedre (BM) or betre (NN), øde (only BM; NN aud regularly inflected), stakkars, free, modern , etc.

- The adjectives liten "klein" and egen (BM) or eigen (NN) "eigen" are completely irregular: masculine liten, egen / eigen , feminine lita, egen / eiga , neutrum lite, eget / eige , plural små / små ( e), egne / own , weak form: lille / litle ~ lisle ~ vesle, egne / own . Example: det egne lille huset (BM) / det eige vesle (or lisle, litle ) huset (NN) "your own little house".

Increase and Compare

- Regular adjectives are increased by - (e) re (BM) / - (a) re (NN) in the comparative and - (e) st (BM) / - (a) st (NN) in the superlative: ærlig - ærligere / ærlegare - the ærligste / ærlegste "honest - honest - the most honest / most honest", ny - nyere / nyare - nyest / nyast ("new"), pen - penere / penare - penest / penast ("beautiful").

- Adjectives in vowels (e.g. øde ) and -s , participles in -et (BM) / -a (NN) as well as compound and multi-syllable adjectives (e.g. factisk, interesting ) are replaced by mer ... (BM ) / meir (NN) and mest ... increased.

- Irregular are (before the fraction line Bokmål , then Nynorsk ):

| mange - flere / fleire - flest | "lots" | mye / mykje - mer / meir - mest | "much" |

| gammel / gammal - eldre - eldst | "old" | ung - yngre - yngst | "young" |

| god - bedre / bere - best | "Well" | vond ~ seine ~ dårlig / dårleg * - verre - ver | "bad" |

| stor - større - størst | "big" | liten - mindre - minst | "small" |

| long - lengre - lengst | "long" | tung - tyngre - tyngst | "heavy" |

| få - færre - færrest | "little" |

* dårlig / dårleg can also be increased regularly

Compare:

| Huset he eldre enn 100 år | "The house is older than 100 years" |

| the huset he så gammelt / gammalt som dette | "That house is as old as this" |

| dette huset he det eldste av de / dei tre | "This house is the oldest of the three" |

Pronouns and adverbs (pronouns and nouns)

Personal pronouns

There is a difference between nominative and accusative only in some personal pronouns in Norwegian. There are gender forms only in the singular of the third person.

| Singular | Plural | |||

| 1st person | any - meg | "I - me, me" | vi - oss | "we us" |

| 2nd person | you - deg | "You - you, you" | dere - dere | "You - you" |

| 3rd person | han - ham / han den - den |

"He - him, him" | de - dem | "They - them / they" |

| hun - hen the - the |

"You - you, you" | |||

| det - det | "That, it - that, it" | |||

| Reflexive | seg | "themselves" | seg | "themselves" |

han - ham / han and hun - henne are only used for persons if the grammatical gender of the word in question is male or female. With the other hand, refers to things male or female.

det is used for people and things when the grammatical gender is neuter.

Examples: mannen - han he here "the man - he is here", kvinna - hun he here "the woman - she is here", døra - he here "the door - she is here", barnet - he here " the child - it is here ”.

The lens forms ham and han are synonymous and have equal rights; Han predominates in the spoken language .

den, det and de also mean “those, that” and “that”. They are also used as a specific article before adjectives.

| Singular | Plural | |||

| 1st person | eg - meg | "I - me, me" | vi / me - oss | "we us" |

| 2nd person | you - deg | "You - you, you" | en / dokker - dykk / dokker | "You - you" |

| 3rd person | han - han | "He - him, him" | dei - dei | "They - them / they" |

| ho - hen / ho | "You - you, you" | |||

| det - det | "That, it - that, it" | |||

| Reflexive | seg | "themselves" | seg | "themselves" |

han and ho are used (as in German, but different than in Bokmål ) not only for people, but also for masculine and feminine things.

The object forms henne and ho in the 3rd person singular feminine and the forms de and dokker in the 2nd person plural are synonymous and have equal rights. Dokker was introduced on the occasion of the spelling reform of 2012, while at the same time the honom (3rd person singular masculine) that had previously been valid alongside han was no longer used .

den, det and dei also mean “those, that” and “that”. They are also used as a specific article before adjectives.

Possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns are inflected in a similar way to adjectives, but there are no weak forms. In Norwegian, the personal pronouns are often followed up; In this case, the associated noun has the specific article appended: mitt hus = huset mitt "my house".

| Singular utrum | Singular neuter | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| my | min / mi | mitt | mine |

| your | din / tue | ditt | dine |

| reflexive | sin / si | sitt | sine |

| our | vår | vårt | våre |

| your | deres (BM) / dykkar (NN) | deres / dykkar | deres / dykkar |

-

sin is used when subject and owner are identical, for all genders in singular and plural: hun sitter i bilen sin (BM) or ho sitt i bilen sin (NN) "she is sitting in her [own] car" <> hun sitter i bilen hennes (BM) or ho sitt i bilen hennar "she is sitting in her car (in that woman's car)"; de sitter i bilen sin "they sit in their own cars".

Otherwise there are hans “from him”, hennes (BM) / hennar (NN) “from her” and deres (BM) / dykkar “from them” (identical to “your”!).

- mi, di, si are the feminine forms in the singular. Unlike min, din, sin, they only appear in front of the following: min mor (BM) = mora mi (BM, NN) "my mother".

- The reenactment (e.g. huset mitt ) is not possible in the following cases: - with all : all sin tid , - with egen (BM) / eigen (NN): sin egen bil , - with genitive attributes: din fars bil .

Interrogative pronouns and adverbs (interrogative pronouns and nouns)

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | |

|---|---|---|

| hvem he det? | does he know? | "who is this?" |

| hvem he det you ser? | do you know? | "Who do you see?" (Literally: "Who is it that you see?") |

| hvem sin form er det? | kven sin form er det? | "Whose car is this?" (Literally: "Whose car is this?") |

| hvem shall any gi det til? | should there be / are there to? | "Who should I give it to?" (Literally: "Who should I give it to?") |

| hva he det? | kva he det? | "what is that?" |

| hvilken, hvilket, hvilke | kva for ein / ei, kva for eit, kva for | "Which / which, which, which (plural)" (Nynorsk literally: "what kind of" etc.) |

| hva slags hus? | kva slags hus? | "What kind of house?" |

| hvor? - hvor (hen)? | kvar? - kvar (til)? | "Where? - where?" |

| når? | når? | "when?" |

| hvordan? | kor ?, korleis? | "how? in which way?" |

| hvorfor? | kvifor? korfor? | "Why?" |

| hvor mange? | kor mange? | "how many?" |

Indefinite pronouns and adverbs

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | |

|---|---|---|

| all hus | all hus | "all houses" |

| hele mitt liv | heal live mitt | "My whole life" (for declination see adjectives) |

| hver dag | kvar dag | "Every / every day" |

| all slags hus | all slags hus | "All kinds of houses" |

| mange hus, flere hus | mange hus, fleire hus | "Many houses, several houses" |

| annen, annet, andre | annan, anna, andre | "Other / other, other, other (plural)" also means "second"! |

| et eller annet sted / gang | eit eller anna sted / nokon gong | "Somewhere / -when" |

Demonstrative pronouns and adverbs

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | |

|---|---|---|

| think, dette, disse | think, dette, desse | "This / this, this, this (plural)" |

| den, det, de | den, det, dei | "Der / die, das, die (plural)" |

| the / det / de ... her | the / det / your ... her | "The / the / that ... here" |

| den / det / de ... the | den / det / dei ... der | "That / that / that" |

| the slags | the slags | "Such, such, such" |

| her - the; hit - dit | her - the; hit - dit | "here there; here / here - there / there " |

| nå - så | no - så | "Now - so" |

| så mange som | så mange som | "as many as" |

Conjugation (inflection of action words)

Norwegian has simplified the originally differentiated personal endings, so that today every verb in all persons has the same ending - which also applies to all Scandinavian languages except Icelandic, Faroese and some Norwegian and Swedish dialects. Until around 1900, personal endings in both written languages were common. Bokmål used the same system that was used in older Danish. On Nynorsk the conjugation was as follows; note the plural endings that correspond to older Swedish:

strong verb singular: å ganga (today å gå ) - eg gjeng - eg gjekk - eg hev gjenge ([to] go - I go - I went - I went)

strong verb plural: å ganga - dei ganga - dei gingo - dei hava gjenge ([to] go - they go - they went - they went)

The infinitive (the basic form)

Verbs whose root ends in a consonant and which are thus multisyllabic have the ending -e as an infinitive ending in Bokmål , and either -e or -a in Nynorsk :

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | German |

|---|---|---|

| å come | å kom (m) e, å kom (m) a | come |

| å discuss | å discuss, å diskutera | to discuss |

| å åpne | å opne, å opna | to open |

Verbs whose stem ends in a vowel do not end in the infinitive:

| Bokmål | Nynorsk | German |

|---|---|---|

| å gå | å gå | go |

| å se | å sjå | see |

| å gi | å gje / gi | give |

Some verbs, which are usually monosyllabic in the infinitive, also have a long form (admittedly only rarely used), more on which more detailed below.

The imperative (the form of command)

There is only one imperative form for the 2nd person singular / plural. It is formed by leaving out the infinitive ending. After certain consonant connections, the final -e can be retained so that the form is easier to pronounce (3rd example); However, this form is considered dialectal, in standard language one says åpn! . A final mm is simplified (2nd example):

| infinitive | Imperative | German |

|---|---|---|

| å gå | gå! | go - go (e)! |

| å come | com! | come - come (e)! |

| å åpne / å opne | åpn! / opne! | open - open! |

The imperative is negated by ikke (Bokmål) / ikkje (Nynorsk):

Drikk ikke så mye! (BM) / drikk ikkje so mykje! (NN) "don't drink so much!"

The simple present (the simple present)

In Bokmål , the simple present tense is formed by adding -r to the infinitive :

| Bokmål | German |

|---|---|

| å gå → går | "Go (go, go, go, go, go, go)" |

| å come → come | "come" |

| å åpne → åpner | "to open" |

In Nynorsk , depending on the conjugation, there is no ending at all (sometimes also with umlaut; in the strong and backward weak conjugation), -r (in monosyllabic strong or weak verbs), -ar (in the first weak conjugation) or -er (on the second weak conjugation):

| Nynorsk | German |

|---|---|

| å drive → driv | "float" |

| å come → kjem | "Come" (umlaut, cf. "he comes") |

| å gå → går | "go" |

| å opne → opnar | "to open" |

| å leve → lever | "Life" |

In Nynorsk , these present tense endings correspond with the various endings of the simple past tense (see below).

The only exceptions are the following verbs (before the slash is the form of Bokmål , then that of Nynorsk ):

| Basic form | Present | German |

|---|---|---|

| å være / vere | he | "To be" (I am, you are ...) |

| å gjøre / gjere | gjør / gjer | "Do, do" |

| å si / be | be / be | "say" |

| å spørre / spørje | spør | "ask" |

| å vite / vite, vete | vet, veit / veit | "knowledge" |

as well as the modal verbs:

| Basic form | Present | German |

|---|---|---|

| å kunne | can | "can" |

| å måtte | må | "have to" |

| å ville | vil | "want" |

| å skulle | scal | "Will" (future tense), "should" |

| å burde / byrje, burde | boron | "should" |

| å gate / gate, gate | goal | "dare" |

| å turve | tarv | "Need" |

The passive

There are two ways to form the passive voice in Norwegian. One works exactly as in German with the auxiliary verb å bli “werden, haben” and the past participle; in Nynorsk , instead of å bli , å verte / verta can also be used (BM = Bokmål, NN = Nynorsk):

| jed blir sett (BM) or eg blir / vert sett (NN) | "I'm being seen" |

| han ble funnet (BM) or han blei / vart funnen (NN) | "He was found" |

In Bokmål there is another possibility to form the passive in the infinitive, in the present and in the simple past of weak verbs of the 2nd and 3rd conjugation (see below): In the s-passive, the present ending -r is replaced by -s or -s is appended to the form of the simple past:

| any ser → any ses / sees | "I see" → "I am seen" |

| han finner → han fins / finnes | "He finds" → "he is found" |

- Infinitive: continuous "to be told"

- Present tense: fortelles "is told" (for all persons)

- Past: continuing old "was told" (for all people)

Examples:

- vinen drikkes av faren "wine is drunk by the father"

- vinduet må ikke åpnes "the window must not be opened = do not open the window!"

In the Nynorsk , the use of the s-passive is much more restricted; it is found almost only after modal verbs (see below) and with Deponentien (these are verbs that only occur in the passive or medium form). The passive or medium ending in Nynorsk is -st:

| møte / møta → møtast | "Meet" → "meet" |

| dei møter → dei møtest | "They meet" → "they meet / each other" |

In Bokmål as in Nynorsk, the passive form is often used in operating instructions as an impersonal request. Together with modal verbs, this form can also be used as an infinitive:

| det kunne ikke selges (BM) or det kunne ikkje seljast (NN) | "It could not be sold" |

| vannet kan drikkes (BM) or vatnet kan drikkast (NN) | "The water can be drunk" |

The other times

In Norwegian you can form as many tenses as in German ( kom "came" [past tense // imperfect], har kommet "am brought" [perfect], hadde kommet "was brought " [past perfect], Skal / vil komm "will come "[Future I], Skal / vil ha come " will have come "[Future II // perfect future]).

For the perfect tenses, the auxiliary verb ha “have” is usually used . være (BM) or vere (NN) "sein" can be used to express a state or a result: hun er gått = "she has gone" → "she has gone". In Bokmål the use of ha or være does not change the verb form, in Nynorsk, on the other hand, the verb after ha remains unflexed, whereas after vere it is usually inflected; see. Bokmål han / hun / det / de har kommet, han / hun / det / de he comet versus Nynorsk han / ho / det / dei har kom (m) e , but han / ho he com (m) en, det he com (m) e, dei er komne . The future tense is formed with the auxiliary verbs skulle or ville or with the construction komm til å .

| any | come | "I'm coming" | |

| any | scal | come | "I will come" |

| any | vil | come | "I will come" |

| any | kommer til å | come | "I will come" |

| any | com | "I came" | |

| any | har | come | "I came" |

| any | hadde | come | "I came" |

| any | scal ha | come | "I will have come" |

| any | vil ha | come | "I will have come" |

| eg | kjem | "I'm coming" | |

| eg | scal | come | "I will come" |

| eg | vil | come | "I will come" |

| eg | kjem til å | come | "I will come" |

| eg | com | "I came" | |

| eg | har | come | "I came" |

| eg | he | come | "I came" (resultant) |

| eg | hadde | come | "I came" |

| eg | var | come | "I came" (resultant) |

| eg | scal ha | come | "I will have come" |

| eg | shall be united | come | "I will have come" (resultant) |

vil and scal can also have a modal meaning (“will” and “should”). From the context one has to deduce whether they are only used as future markers.

Norwegian has three weak conjugations for the simple past .

- The first conjugation has either the endings -et or -a in Bokmål , and always -a in Nynorsk . It applies to verbs with several consonants with the exception of ll, mm, ld, nd, ng :

- åpne> jeg åpnet / åpna (BM) or opne> eg opna (NN) "open> I opened"

- The second conjugation has the ending -de (after diphthong, v or g ) or -te (after simple consonants or ll, mm, ld, nd, ng ) in both Bokmål and Nynorsk :

- leve> jeg levde (BM) or leve> eg levde (NN) "I lived"

- mene> jeg mente (BM) or my> eg meant (NN) "I meant"

- The third conjugation for weak verbs without an infinitive ending has the ending -dde in both Bokmål and Nynorsk :

- tro> jeg trodde (BM) or tru> eg trudde (NN) "I believed".

In Nynorsk , these various past tense endings correspond to the various endings in the present tense, see:

- eg opnar <> eg opna "I open" <> "I opened"

- eg lever <> eg levde "I live" <> "I lived"

- eg trur <> eg trudde "I believe" <> "I believed"

Norwegian (like English) most often uses the simple past. The perfect is u. a. used when there is no time specification or when it comes to persistent states.

Norwegian has between a hundred and fifty and two hundred strong and irregular verbs. For example: dra, dro, dratt (Bokmål) = dra, drog, drege (Nynorsk) "pull, pulled, pulled" = English draw, drew, drawn = "pull, pulled, pulled" ( dra is etymologically related to "wear." ", Cf. also" carry, carried, carried ").

In Bokmål, the past participle (perfect) always ends in -t , never in -en : drikke, drakk, drukket , but in German: “drink, drank, drunk en ”. In Nynorsk, on the other hand, the past participle is inflected after the auxiliary verb vere : han / ho he come, det he come, dei he komne “he is, it is, they have come”, but not after ha : han / ho / det / dei har read "he has, it has, you have read".

While the totality of the inflected forms of Nynorsk is generally more complex than that of Bokmål , the reverse case applies to strong verbs: The first strong class of Bokmål includes the following verb types: gripe - gre (i) p - grepet , skri (de) - skred / skrei - skredet, bite - be (i) t - bitt, third - dre (i) t - third, klive - kleiv - klevet / klivd, ri (de) - red / rei (d ) - ridd, li (de) - led / lei (d) - lidt ... In Nynorsk, on the other hand, all verbs in this class are inflected according to only two types: 1) gripe - greip - gripe, bite - beit - bite, third - three - third, klive - kleiv - klive and 2) ri (de) - reid - ride / ridd / ridt, li (de) - sorrow - lide / lidd / lidt, skri (de) - skreid - skride / skridd / skridt .

Most of the strong verbs of Nynorsk are conjugated according to the following main types:

- bit - bit - bit

- bryte - bride - bread

- drikke - drakk - drukke

- bresta - brast - broste (short vowels) or bere - bar - bore (long vowels)

- read - read - read

- fare - for - fare

- ta (ke) - tok - teke

- la (te) - lét - late (long vowels) or halde - heldt - halde (short vowels)

To make a similar summary for Bokmål is almost hopeless, since in this variety the groups corresponding to the above rows 1–4 are very strongly fragmented. The main reason for this is an inconsistent standardization in which Danish tradition, Southeast Norwegian dialects and other criteria are mixed up. A list of the more important irregular verbs of Bokmål can be found at the external links.

Prepositions, conjunctions, adverbs

Prepositions

The range of meanings of the Norwegian prepositions cannot simply be transferred to their German equivalent. In Norwegian it is called å klatre i et tre with the preposition i "in", while in German it means " to climb a tree". In the following, only the most important prepositions are listed with a general translation (in the case of double forms, Bokmål before the dash, then Nynorsk):

- i: in

- ved: an

- til: to, after

- på: on

- hos: at

- fra / frå: from (...)

- med: with

- for: for (as conjunction: "then")

- foran: before (locally)

- uten / utan: without

- for: before

- av: from (corresponds to English of )

Often there are combinations of ved siden / sida av “on the side of = next to”, strange to “to”.

Conjunctions (connecting words)

The most important conjunctions are (in double forms before the fraction line Bokmål, then Nynorsk):

Associating:

- og: and

- også (Nynorsk also òg ): also

- men: but, but

Subordinating:

- fordi: because

- hvis / viss: if

- at: that

- så: so, then

- om: if, if

- da: as, there, then, because

- for before, before

Combinations: selv om “even if, although”, så at “so”.

The relative pronoun in the nominative and accusative is som - in the accusative it can be omitted. Prepositions are placed at the end of the sentence, the relative pronoun is omitted (the examples in Bokmål ): huset som er hvitt "the house that is white", huset (som) Any ser er hvitt "the house that I see is white", huset hun bor i "the house where she lives".

In Norwegian there is (almost) no subjunctive, so the time of indirect speech must be aligned with that of the introductory verb.

Adverbs

- ikke / ikkje: not

- lighter ikke / lighter ikkje: not either

- jo: yes, yes

If there is a subordinate conjunction at the beginning of a sentence, the basic sentence order does not change, but the positions of adverbs such as ikke / ikkje do .

Numerals

Basic numbers

| 0 - zero | |||

| 1 - BM én, éi / én, ett 1 - NN éin, éi, eitt |

11 - elleve | ||

| 2 - to | 12 - tolv | 20 - tjue | 22 - tjueto |

| 3 - tre | 13 - pedal | 30 - tretti | 33 - trettitre |

| 4 - fire | 14 - fjorten | 40 - førti | 44 - førtifire |

| 5 - fem | 15 - far | 50 - femti | 55 - femtifem |

| 6 - sec | 16 - seconds | 60 - seksti | 66 - secstiseks |

| 7 - sju 7 - BM also syv |

17 - sytten | 70 - sytti | 77 - syttisju |

| 8 - åtte | 18 - atten | 80 - åtti | 88 - åttiåtte |

| 9 - ni | 19 - nitten | 90 - nitti | 99 - nittenni |

| 10 - ti | 100 - BM (ett) hundre 100 - NN (eitt) hundre |

101 - BM (én) hundre and én 101 - NN (éin) hundre og éin |

|

| 1000 - BM (ett) tusen 1000 - NN (eitt) tusen |

1001 - BM (ett) tusen og én 1001 - NN eitt tusen og eitt |

The numbers of the type tens + ones formed according to the Swedish and English pattern, i.e. about 51 - femtién / femtiéin, 52 - femtito, 53 - femtitre, 54 - femtifire, 55 - femtifem, 56 - femtiseks, 57 - femtisju, 58 - femtiåtte, 59 - femtini, were officially introduced by parliamentary resolution in 1951. Previously, these numbers were officially formed as in Danish and German, i.e. one + og ("and") + tens: 51 - énogfemti / éinogfemti, 52 - toogfemti, 53 - treogfemti, 54 - fireogfemti, 55 - femogfemti, 56 - seksogfemti, 57 - sjuogfemti, 58 - åtteogfemti, 59 - niogfemti . In everyday language, however, this latter method of counting is still widespread today; Most people use one or the other system alternately - the new system has only fully established itself with telephone numbers. Also unofficial and yet widespread are the Riksmål's tyve instead of tjue for 20 and tredve instead of tretti for 30.

Ordinal numbers

The ordinal numbers of 1 and 2 are irregular: første / fyrste "first (r / s)", others "second (r / s)". The others are formed, as in all Germanic languages, by adding a dental suffix (in Norwegian -t, -d; followed by the ending -e ), whereby numerous smaller and larger irregularities occur. For the cardinal numbers that are based on a vowel, an n is inserted in front of the dental at 7th to 10th and, based on the latter, at 20th to 90th .

| 0. - - | ||

| 1. - første 1. - NN also fyrste |

11. - ellevte | 10. - BM - tiende 10. - NN - tiande |

| 2. - other | 12. - tolvte | 20. - BM - tjuende 20. - NN - tjuande |

| 3. - tredje | 13th - BM - stepping 13th - NN - trettande |

30. - BM - trettiende 30. - NN - trettiande |

| 4. - fjerde | 14. - BM - fjortende 14. - NN - fjortande |

40. - BM - førtiende 40. - NN - førtiande |

| 5. - femte | 15. - BM - femtende 15. - NN - femtande |

50. - BM - femtiende 50. - NN - femtiande |

| 6. - sjette | 16. - BM - second end 16. - NN - second position |

60th - BM - secstiende 60th - NN - secstiande |

| 7. - BM - sjuende , syvende 7. - NN - sjuande |

17. - BM - syttende 17. - NN - syttande |

70th - BM - syttiende 70th - NN - syttiande |

| 8. - BM - åttende 8. - NN - åttande |

18. - BM - attende 18. - NN - attande |

80. - BM - åttiende 80. - NN - åttiande |

| 9. - BM - niende 9. - NN - niande |

19th - BM - nittende 19th - NN - nittande |

90th - BM - nittiende 90th - NN - nittiande |

| 100.- hundrede | ||

| 1000th - end of the act |

sentence position

The Norwegian sentence has the basic word order subject - predicate (verb) - object. The sentence order is largely retained even after subordinate conjunctions, except that the position of the negation particles shifts before the infinite verb: fordi han ikke ville betale "because he did not want to pay".

Inversion (interchanging the finitive predicate and the subject) occurs when an adverb, the object or a subordinate clause is at the beginning of the sentence instead of the subject: i tomorrow shall come, " tomorrow I shall come", takk scal you ha! " You should have thanks !", Hvis det regner, blir jeg hjemme = rain det, blir jeg hjemme "if it rains, I'll stay at home" = "if it rains, I'll stay at home".

Using the field scheme of Paul Diderichsen , a main clause is structured as follows:

| Apron | finite verb |

subject | Adverb A: sentence adverbial |

infinite verb |

Object (s) | Adverb B: adverbial of type, place and time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dessverre | hadde | ho | ikkje | funne | pengane | i går |

| I morgon | sculle | dei | sikkert | løyse | saka | rettvist |

| Bilane | køyrde | midt i gata | ||||

| Dei | kunne | vel | gje | hen gåver | i dag likevel | |

| Kva | bright | you |

Apart from the inflected verb, all parts of the sentence can be used in advance, but most often the subject. If another part of the sentence than the subject is in the forefront, its actual place remains vacant.

In the subordinate clause , the sentence adverbial always comes before the verb or verbs and immediately after the subject:

| Binding field | subject | Adverb A: sentence adverbial |

finite verb |

infinite verb |

Object (s) | Adverb B: Adverbial of place and time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at | Eve | ikkje | ville | gje | han gåver | to jul |

| dersom | Tove | snart | kunne | møte | han | i byen |

Etymological and dialectological notes

About the structure

Compared to today's Icelandic and Faroese, Norwegian lacks the following grammatical structures: case (with the exception of a kind of genitive), noun classes, personal endings (an inflected standard form applies to each time), subjunctive (the remainders that have been preserved are lexicalized), special forms for the Plural of the past tense and the strong verbs in the past tense. The structure of Norwegian / Danish / Swedish roughly corresponds to that of New English, while that of Icelandic / Faroese is roughly similar to that of Old High German. The relationships are more differentiated in the morphology: In the area of the plural formation of nouns and the abutments of the strong verb, Nynorsk is closer to Icelandic, Faroese and Swedish, while Bokmål is closer to Danish.

In phonetic terms, Norwegian is close to German in certain respects: weakening of the final vowels in Bokmål zu Schwa , loss of the Old Norse th-sound (þ, ð), suppository-R in some Western dialects. Nynorsk then resembles the German in terms of its wealth of diphthongs. In contrast to German, however, all Scandinavian languages did not take part in the High German sound shift , which is why there are many differences in the consonants ( t = z / ss / ß , k = ch , p = pf / ff / f , d = t ). Another fundamental difference between Norwegian and German is that Norwegian (like Swedish) has a musical accent in addition to the pressure accent; see accents in the Scandinavian languages .

The mainland Scandinavian languages were strongly influenced by Low German foreign words during the Hanseatic League . Almost entire sentences can be formed without words originally in North Germanic. This represents a significant difference to Icelandic and Faroese , which successfully endeavor to keep their languages clean of foreign words of all kinds ( language purism ).

To the cases

The mainland Scandinavian languages (i.e. most of the Danish, Swedish and Norwegian dialects and the respective high-level languages) have not retained the Old Norse case system ( apart from genetic -s and some of the personal pronouns) (cf. Icelandic hundur, hunds, hundi, hund "a dog , a dog, a dog, a dog ”). In Old Norse , some prepositions required the genitive, others the dative, which is why these cases still occur in certain fixed idioms, for example: gå til bords (genitive with the ending -s ) "go to table" versus gå til stasjonen "go to the station" , være / vere på tide (dative with the ending -e ) “to be in time” versus være / vere på taket “to be on the roof”.

Lively dative forms still occur in the inner Norwegian dialects , such as båten "das Boot", dative singular båté, båta "dem Boot", plural båta (r) ne "the boats", dative plural båtå (m) "the boats".

The Norwegian suffix -s , which can be added to any noun (see above), historically goes back to the genitive of the a-declension, but has been generalized in the course of language history. In Old Norse had i- and u-stems, weak declension words and feminine never this ending (see neuisländisch. Hunds "a dog" - vs.. Vallar / "a field" afa "grandfather" / ömmu "grandmother" in the plural valla, afa, amma ).

To the infinitive

In Old Norse, -n was dropped at the end of the word, so the infinitive in Norwegian ends in -e or -a (cf. New High German "-en", Old High German and Gothic "-an"). On a dialectal level, the infinitive has the ending -a (e.g. lesa "read", finna "find") in southwestern Norway , in northwestern Norway -e ( read , finne); In Eastern Norway, -a applies if the word stem was light in Old Norse, and -e if the word stem in Old Norse was difficult (e.g. lesa versus finne ). Apokope occurs in the dialect of Trøndelag , i. H. the infinitive can appear without an ending (e.g. les , finn ). The Nynorsk reflects these relationships in that the infinitive can optionally end in -e or -a .

To the present and past tense

The verb endings -ar and -er of the weak verbs correspond to the endings of the 2nd and 3rd person singular in Old Norse; see. Old and New Icelandic talar, segir "[you] speak, say, [he] speaks, says". The zero ending of strong verbs in Nynorsk , e.g. B. without umlaut han bit "he bites" to Inf. Bite , han SKYT "he shoots" to Inf. Skyte , with an umlaut han tek "he takes" to Inf. Ta (ke) , han kjem "he comes" to Inf . kom (m) e , also corresponds to the original 2nd and 3rd person singular, cf. Old Norwegian / Old Icelandic han bítr “he bites”, han skytr “he shoots”, han tekr “he takes”, han kømr “he comes”, because according to the law, many dialects come across here in accordance with the procedure Old Norwegian / Old Icelandic hestr > New Norwegian hest "Horse" from the actual inflection ending -r , and the corresponding forms were therefore also adopted in the standard variety. However, there are also dialects where the Old Norwegian ending -r as -er or -e has been retained; In dialectal terms, in addition to standardized han bit, han skyt, han tek, han kjem, there is also han bite (r), han skyte (r), han teke (r), han kjeme (r) . The umlautless Bokmål form kommer corresponds to both the dialectal sound of south- east Norway and the Danish form.

Today these standard language forms Bokmål kommer = Nynorsk kjem apply to all persons in the singular and plural. In some inner Norwegian dialects there is still a number inflection, but only one form for singular and plural: present eg / du / han / ho drikk <> vi / de / dei drikka , past tense eg / du / han / ho drakk < > vi / de / dei drukko - same as older Swedish.

Some of the Norwegian dialects also have a subjunctive in the past tense, such as eg vore or eg vøre , German "I would be".

For the juxtaposition of short and long forms

Originally, all verbs in the infinitive had two or more syllables; in some verbs, however, the consonant ending at the stem and consequently the infinitive ending has also disappeared: cf. English give "to give" opposite Bokmål gi; in the past tense gav (secondary form: ga ) “gave” the v (like in English gave ) has been retained.

Nynorsk usually knows both long and short forms of these verbs, in the case mentioned the infinitive variants gje and gjeve / gjeva "give", whereby in practice the short variant gje in the infinitive, on the other hand, the variant gjev derived from the long form in the present tense prefers becomes. In the past tense, however, only gav derived from the long form applies , in the past participle gjeve and gitt are in turn next to each other. A similar case is infinitive ta (rarely take / taka ) “to take”, present tek or tar , simple past tense tok , past participle teke or tatt . Somewhat different, in that the form derived from the short form can also be in the simple past , for example ri “riding” with the present tense rid or rir , simple past reid or rei , past participle ride or ridd / ridt .

Others

The language code according to ISO 639 is for bokmål nb or nob(earlier no) and for nynorsk nn or respectively nno. For the Norwegian language as a whole there are codes noor nor.

Professional e-athlete Ørjan Larsen is considered to be one of the most popular mediators of the Norwegian language today. He initiated various workshops on language learning at numerous major international events and received an award from the Norwegian Society for Language Understanding for this in 2018.

See also

literature

Grammars:

- Jan Terje Faarlund, Svein Lie, Kjell Ivar Vannebo: Norsk referansegrammatikk . Universitetsforlaget, Oslo 1997. (3rd edition 2002, ISBN 82-00-22569-0 ) (Bokmål and Nynorsk).

- Olav T. Beito: Nynorsk grammatikk. Lyd- og ordlære. Det Norske Samlaget, Oslo 1986, ISBN 82-521-2801-7 .

- Kjell Venås: Norsk grammar. Nynorsk. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo 1990. (2nd edition ibid. 2002, ISBN 82-13-01972-5 ).

- Åse-Berit Strandskogen, Rolf Strandskogen: Norsk grammatikk for utlendinger. 6th edition. Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, Oslo 1991, ISBN 82-05-10324-0 .

Introductions and textbooks:

- Janet Duke, Hildegunn Aarbakke: Nynorsk. In: Janet Duke (Ed.): EuroComGerm. Learn to read Germanic languages. Volume 2: Less commonly learned Germanic languages. Afrikaans, Faroese, Frisian, Yenish, Yiddish, Limburgish, Luxembourgish, Low German, Nynorsk. Shaker, Düren 2019, ISBN 978-3-8440-6412-4 , pp. 267-293.

- Eldrid Hågård Aas: Langenscheidt's practical language course in Norwegian . Langenscheidt Verlag, Munich / Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-468-80373-4 (concerns Bokmål).

Dictionaries:

- Bokmålsordboka and Nynorskordboka, ed. by the Avdeling for leksikografi ved Institutt for lingvistiske og nordiske studier (ILN) ved Universitetet i Oslo, in cooperation with the Språkrådet, several editions; digital: Bokmålsordbok | Nynorskordboka .

- Norsk Ordbok . Ordbok about the norske folkemålet and the nynorske skriftmålet. Volumes 1–12, Oslo 1965–2016.

- Norsk Riksmålsordbok. 1937–1957 (four volumes). Reprint 1983 (six volumes), Supplement 1995 (2 volumes), revision since 2002.

- K. Antonsen Vadøy, M. Hansen, L. B. Stechlicka: Thematic dictionary New Norwegian - German / German - New Norwegian. Ondefo-Germany 2009, ISBN 978-3-939703-49-5 .

- K. Antonsen Vadøy, M. Hansen, L. B. Stechlicka: Tematisk Ordbok Nynorsk - Tysk / Tysk - Nynorsk . Ondefo, Hagenow 2009, ISBN 978-3-939703-49-5 .

Various:

- Egil Pettersen: The standardization work of the Norwegian Language Council (Norsk Språkråd). In: Robert Fallenstein, Tor Jan Ropeid (Ed.): Language maintenance in European countries. Writings of the German Institute of the University of Bergen, Bergen 1989, ISBN 82-90865-02-3 .

- Åse Birkenheier: Ivar Aasen - the man who created a new, old language. In: dialog. Announcements from the German-Norwegian Society e. V., Bonn. No. 42, Volume 32 2013, pp. 24–27.

- Kari Uecker: Norwegian with its many variants. Regional languages and dialects are gaining popularity. In: dialog. Announcements from the German-Norwegian Society e. V., Bonn. No. 42, Volume 32 2013, p. 57.

Web links

- Norwegian Language Council (Norwegian, also information in English, German, French)

- Ivar Aasen-tunet (Center for Nynorsk)

- German-Norwegian dictionary, plus forum and short grammar

- List of irregular verbs from Bokmål

Individual evidence

- ^ Koenraad De Smedt, Gunn Inger Lyse, Anje Müller Gjesdal, Gyri S. Losnegaard: The Norwegian Language in the Digital Age (= White Paper Series). Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 9783642313882 , p. 45, doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-642-31389-9 : "Norwegian is the common spoken and written language in Norway and is the native language of the vast majority of the Norwegian population (more than 90%) and has about 4,320,000 speakers at present. "

- ↑ Sprog. In: norden.org. Nordic Council , accessed 24 April 2014 (Danish).

- ↑ Vidar 1832 No. 15, p. 115.

- ↑ Språkrådet: Nynorskrettskrivinga Skal bli enklare , accessed on November 29, 2011 (Nynorsk)

- ↑ Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar (målvedtaksforskrifta) , amended on January 29, 2020, lovdata.no, accessed on February 6, 2020

- ↑ SAMPA for Norwegian (English)

- ↑ Finn-Erik Vinje: Om å få folk til å telle annerledes, in: Språknytt 4/1991 (accessed on July 28, 2014).

- ↑ Almost all sentence examples from Kjell Venås: Norsk grammatik. Nynorsk. Oslo 1990, 2nd edition. ibid. 2002, p. 152 ff.

- ↑ Ørjan Larsen - About me