Germanic languages

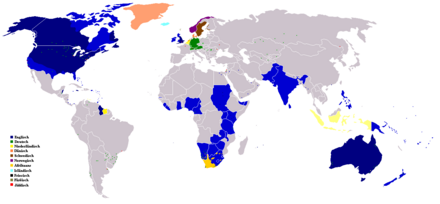

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family . They span around 15 languages with around 500 million native speakers , nearly 800 million including secondary speakers . A characteristic phenomenon of all Germanic languages compared to the other Indo-European languages are the changes in consonantism due to the Germanic sound shift .

The purpose of this article is to present the Germanic languages as a whole. Reference is made to subgroups and individual languages and their dialects . The primitive Germanic language is dealt with in a separate article.

The great Germanic languages

A total of ten Germanic languages each have more than a million speakers.

- English is the Germanic language with the most speakers, with around 330 million native speakers and at least 500 million second speakers.

- German is spoken by around 100 million native speakers and at least 80 million second speakers.

- Dutch (25 million)

- Swedish (10 million)

- Afrikaans (6.7 million, with secondary speakers 16 million)

- Danish (5.5 million)

- Norwegian (5 million; Bokmål and Nynorsk )

- Low German (approx. 2 million; position as a separate language disputed)

- Yiddish (1.5 million)

- Scots (1.5 million; position as a separate language disputed)

The west-north-east structure of the Germanic languages

The Germanic languages are usually divided into West, North and East Germanic (see the detailed classification below). The language border between North and West Germanic is now marked by the German-Danish border and used to be a little further south on the Eider .

The West Germanic languages include: English , German , Dutch , Afrikaans , Low German , Yiddish , Luxembourgish , Frisian, and Pennsylvania Dutch .

These include: Swedish , Danish , Norwegian , Faroese, and Icelandic .

All East Germanic languages are extinct. The best surviving East Germanic language is Gothic .

The classification of the Germanic languages

Classification of today's Germanic languages

The Germanic branch of Indo-European today comprises 15 languages with a total of around 500 million speakers. Some of these languages are only considered dialects by some researchers (see below). These 15 languages can be classified according to their degree of relationship as follows (the number of speakers refers to native speakers):

Germanic (15 languages with a total of 490 million speakers):

- 1. West Germanic:

-

Standard German:

- German (100 million; 180 million including second speaker)

- Yiddish (1.5 million)

- Luxembourgish (Lëtzebuergesch) (300,000)

- Pennsylvania Dutch (100,000)

-

Low German:

- Low German (approx. 2 million)

- Plautdietsch (500,000)

- Lower Franconian :

- Frisian languages (400,000) ( West Frisian , North Frisian , East Frisian [ Saterlandic ])

- English (340 million; at least 850 million including second speakers)

-

Standard German:

- 2. North Germanic:

- 1. West Germanic:

The basis of this classification is the web link “Classification of Indo-European Languages”, which for Germanic is based primarily on Robinson 1992. The current number of speakers is taken from Ethnologue 2005 and official country statistics.

Since the boundaries between languages and dialects are fluid, z. For example, Luxembourgish, Plautdietsch, Pennsylvanian and Low German are not viewed as languages by all researchers , while Schwyzerdütsch and Scottish (Scots) are viewed by others as further independent West Germanic languages. Another example: The two variants of Norwegian ( Bokmål and Nynorsk ) are considered separate languages by some Scandinavians, with Bokmål moving closer to Danish and Nynorsk closer to Icelandic-Faroese.

Historical classification

While the above classification only provides a breakdown of the Germanic languages that exist today, the following representations should provide a historical insight, as the extinct Germanic languages are also listed. Schematic representation of the separation of the historical Germanic languages up to the 9th century, according to Stefan Sonderegger :

| 1st millennium BC Chr. | Early / Urgermanic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Centuries before and after Christ | Middle / Common Germanic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4th century | Late Germanic | Oder-Vistula Germanic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5th century | South Germanic | North Germanic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhine-Weser Germanic | Elbe Germanic | North Sea Germanic | Primordial Nordic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6th to 9th centuries | Old Franconian | Old Bavarian / Old Alemannic |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Dutch | Old High German | Old Saxon | Old Frisian | Old English | Old Norse | Gothic † | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the table below, unassigned, but accessible intermediate links are marked with *. In particular , there has not yet been a complete consensus on the historical structure of the West Germanic languages , but the following historically oriented presentation (according to Maurer 1942, Wiesinger 1983, dtv-Atlas Deutsche Sprache 2001, Sonderegger 1971, Diepeveen, 2001) reflects the research direction that is predominantly represented. The West Germanic is not understood as an original genetic unit; it only developed later through convergence from its components North Sea Germanic , Weser-Rhine Germanic and Elbe Germanic . From this representation it is also clear that the dialects of German belong to different branches of the “West Germanic”, so German can only be integrated into a historical Germanic family tree in the form of its dialects. Explanation of the symbols: † stands for an extinct language. Ⓢ symbolizes that there is a standardized written form for this variety or dialect group.

-

* Germanic

-

Common Germanic

-

Oder-Vistula Germanic ( East Germanic )

-

Gothic †

- Crimean Gothic † (possible, controversial)

- Vandal †

- Burgundian †

-

Gothic †

-

Late Germanic

- North Germanic

-

West Germanic ( South Germanic )

-

Rhine-Weser Germanic

-

Old Franconian †

-

West Old Franconian ( Lower Franconian )

-

Old Dutch †

-

Middle Dutch †

-

New Dutch †

-

Dutch Ⓢ

- West Flemish

- East Flemish

- Brabantian

- Dutch

- Limburgish

- Zeeland

- Kleverländisch (has standard German as the umbrella language since the 19th century )

- Afrikaans (semi-Creole language) Ⓢ

-

Dutch Ⓢ

-

New Dutch †

-

Middle Dutch †

-

Old Dutch †

- East Franconian ( subdivided varieties belong to Standard German after the 9th century )

-

West Old Franconian ( Lower Franconian )

-

Old Franconian †

-

North Sea Germanic

- Old Frisian †

- Old English †

-

Old Saxon †

-

Middle Low German †

- (New) Low German

- Nedersaksisch (Has Dutch as an umbrella / cultural language since the 15th century )

- Lower Saxon / West Low German (has German as the umbrella / cultural language since the 15th century )

- East Low German

- (New) Low German

-

Middle Low German †

- Plautdietsch (mixed form of East Low German and Dutch varieties)

-

Elbe Germanic

- Semnonian †

- Hermundurian †

- Quadic †

- Marcomannic †

- Old Bavarian †

- Old Alemannic †

- Longobard †

-

Old High German †

-

Middle High German †

-

Yiddish

- West Yiddish

- East Yiddish

-

New High German †

-

German Ⓢ

- East Franconian

-

Bavarian

- Northern Bavarian

- South Bohemian

- Middle Bavarian-Austrian

- South Bavarian-Tyrolean

- Alemannic

- Swabian

-

German Ⓢ

-

Yiddish

-

Middle High German †

-

Rhine-Weser Germanic

-

Oder-Vistula Germanic ( East Germanic )

-

Common Germanic

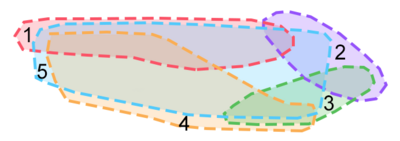

Germanic language relationship based on the wave theory

Legend:

Although the family tree theory offers an adequate model to represent the processes of the splitting off of speech, the wave theory provides this achievement for the representation of the interlingual contacts. According to the wave theory, spatially and / or temporally neighboring linguistic varieties have a largely identical language inventory. The edge line of each language area represents the maximum diffusion of the innovation that originates from an innovation center. Five innovation centers are identified within the wave theory: East Germanic , Elbe Germanic , North Sea Germanic , Rhine-Weser Germanic and North Germanic , from which today's or historical Germanic languages are said to have largely or partially formed.

By the 5th century BC It is very difficult to make specific dialect distinctions within the Germanic varieties, if one refrains from separating the East Germanic Goths . The undeniable Gothic-Nordic isoglosses suggest, however, that these are innovations that arose in the restricted area in which the Goths settled and that only found widespread use in Scandinavia after the Goths left. Later contacts between the Gothic and Elbe Germanic can only be sparsely documented, but historically very likely when the Goths settled in around the 1st century BC. BC to the 1st century AD , along the middle and lower course of the Vistula .

In the course of the 5th century , caused by intensive commercial traffic, a kind of linguistic union developed with the North Sea Germanic , to which the oldest phases of English, Frisian, Old Saxon and, to a lesser extent, North Germanic belong. North Sea Germanic does not designate a branch of the Germanic family tree, but a process that resulted in more recent correspondences (so-called Ingwaeonisms ). The Old Saxon language was basically derived from North Sea Germanic, but shows from the 8th to 9th. Century stronger influences of the south adjoining German, which arose essentially from the Elbe Germanic. The descendants of the Old Franconian , which mainly originated from the Rhine-Weser Germanic, were, apart from Dutch and the Lower Rhine dialects , thoroughly shaped in the early Middle Ages by the second sound shift or by Elbe Germanic innovations.

Development of German

The separation and constitution of the German language from Germanic could best be understood as a threefold linguistic-historical process:

- The increasing differentiation from the late Common Germanic to the South Germanic to the Elbe Germanic and, to a lesser extent, to the Rhine-Weser Germanic, on which the early medieval tribal dialects are based.

- The integration in the Franconian Reich Association to Old High German .

- The written or high-level language layering on High German (more precisely: East-Central German and South-East German) basis, whereby Low German was also finally incorporated into the German language, although an influence from High German can be ascertained since Old High German times.

| Old Franconian | Old Alemannic | Old Bavarian | Longobard 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| West Franconian 2 | Old Dutch | Old Middle and Old High Franconian | Old Upper German | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Saxon | Old High German | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Middle Low German | Middle High German | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Low German | Standard German | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| German | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1 In the 9th / 10th Century.

2 Extinguished in the 9th century.

Germanic writings

Since around the 2nd century AD, the Germanic tribes have used their own characters, the runes . The so-called "older Futhark " was created, an early form of the rune series that was in use until around 750 AD. The traditional Gothic Bible of the 4th century has its own script, namely the Gothic alphabet developed by Bishop Wulfila . Later, the Germanic languages were written with Latin letters. Examples of modified letters are the yogh ( Ȝ ) and the latinisierten Rune Thorn ( þ ) and Wunjo ( ƿ ).

Germanic word equations

The following tables compile some word equations from the areas of kinship terms , body parts , animal names , environmental terms , pronouns , verbs and numerals for some old and new Germanic languages. One recognizes the high degree of relationship between the Germanic languages as a whole, the particular similarity between the West Germanic and North Germanic languages, the greater deviation of the Gothic from both groups and, ultimately, the relationship between Germanic and Indo-European (last column, here the deviations are of course greater). The laws of Germanic (first) and High German (second) sound shifting can also be checked here (detailed treatment in the next section). Since the Germanic and Indo-European forms have only been reconstructed, they are marked with an *.

All Germanic nouns

The following nouns are represented in almost all Germanic languages and can also be reconstructed for Urindo-European :

| German | Old High German | Dutch | Old Dutch | Old Saxon | English | Old English | Swedish | Icelandic | Old Norse | Gothic | Germanic | Urindo-European |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| father | fater | Vader | fader | fadar | father | fæder | far | faðir | faðir | fadar | * fađer | * pətér |

| mother | muoter | moeder | muoder | modar | mother | modor | mor | móðir | móðir | - | * mōđer | * mater |

| Brothers | bruoder | broe (de) r | bruother | brođar | brother | office | bror | bróðir | bróðir | broþar | * brōþer | * bhrater |

| sister | swester | additional | sweet | swestar | sister | sweostor | syster | systir | systir | swistar | * swester | * suesor |

| daughter | tohter | wick | dohter | dohtar | daughter | dohtar | yolk | dóttir | dóttir | dahhtar | * thouter | * dhugəter |

| son | sunu | zoon | suno | sunu | son | sunu | son | sonorous | sunr | sunus | * sunuz | * suənu |

| heart | herza | hard | herta | herta | heart | heorte | hjärta | hjarta | hjarta | hairto | * χertōn | * kerd |

| knee | knio | knee | knee | knio | knee | cneo | knä | kné | kné | kniu | * knewa | * genu |

| foot | fuoz | voet | fuot | fōt | foot | fot | fot | fótur | fótr | fetus | * fōt- | * pod |

| Aue 1 | ouwi | ooi | ouwi | ewwi | ewe | eowu | - | - | ær | aweþi | * awi | * owi |

| cow | kuo | koe | kuo | ko | cow | cu | ko | kýr | kýr | - | * k (w) ou | * gwou |

| Moose | elaho, eliho | eland | elo | elaho | elk | eolh, eolk | alg | elgur | elgr | - | * elhaz, * algiz | * h₁élḱis, * h₁ólḱis |

| Mare | meriha | merrie | marchi | merge | mare | mere, miere | marr | - | merr | * marhijō | *mark- | |

| pig | swin | between | swīn | swin | swine | swin | svin | svín | svín | swein | * swina | * sus / suino |

| dog | hunt | hond | hunda | dog | hound 2 | dog | dog | hundur | Hundr | dog | * χundaz | * kuon |

| water | wazzar | water | watar | watar | water | wæter | vatten | vatn | vatn | vato | * watōr | * wódr̥ |

| Fire | for | vuur | for | for | fire | fyr | fyr | - | for | - | * for, * for | * péh₂ur |

| ((Tree)) 3 | - | (boom) | (bom) | trio | tree | treo (w) | trad | tré | tré | triu | * trevam | * deru |

| ((Wheel)), ( shaft ) | - | wiel | wēl | - | wheel | hweol | hjul | hjól | hvél | - | * hwehwlą | * kʷékʷlo- |

1 New High German Aue = mother sheep (outdated, scenic)

2 New English hound = hunting dog

3 But compare the second syllable in Flie-der, Holun-der

However, there are also some Germanic nouns that do not seem to be inherited from the Urindo-European :

| German | Old High German | Dutch | Old Dutch | Old Saxon | Old English | English | Swedish | Icelandic | Old Norse | Gothic | Urgermanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plow | Pfluog | ploeg | pluog | plog | plōh | plow, plow | plog | plógur | plógr | * plogaz, * ploguz | |

| hand | hant | hand | other | hond | hand | hand | hand | heck | heck | handus | * χanduz |

All Germanic pronouns

| German | Old High German | Dutch | Old Saxon | Old English | English | Old Norse | Gothic | Germanic | Urindo-European |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ih | ik | ik | ic | I. | ek | ik | * ek | * eg (om) |

| you | you | jij, 4 mnl each . you |

thu | þu | you arch. thou |

þú | þu | * þu | * do |

| who | (h) who | how | hwe | hwa | who | hvat | hwas | * χwiz | * kwis |

- 4 In Middle Dutch, the 2nd person singular ( du ) has been replaced by the 2nd person plural (gij, later jij).

- 5 In English, the 2nd person singular ( thou , object thee ) has been replaced by the 2nd person plural (initially ye , object you).

All Germanic verbs

| German | Old High German | Luxembourgish | Dutch | Afrikaans | Old Saxon | Old English | English | Old Norse | Gothic | Germanic | Urindo-European |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eat | ezzan | eat, eat | eten | eet | etan | etan | eat | eta | itan | * etaną | * ed |

| ((wear)) 6 | beran | ((droen)) | bare | beran | beran | bear | bera | bairan | * beraną | * bher- | |

| drink | drinkable | drenken | drink | drink | drinkan | drincan | drink | drekka | drigkan | * drinkaną | * dʰrenǵ- |

| (he knows | wheat | wees | weet | weet | wēt | wāt | . | veit | wait | * wait | * woida |

6 is related to New High German gebären .

All Germanic numerals

Almost all Germanic numerals are inherited from the Urindo-European :

| German | Old High German | Luxembourgish | Old Dutch | Dutch | Afrikaans | Old Saxon | Old English | English | Old Norse | Gothic | Germanic | Urindo-European |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one) | a | een (t) | ēn | een | een | en | on | one | an | ains | * aina | * oino |

| two | zwen / two / two | two | twēne | twee | twee | twa / two / twe | twa / tu | two | tveir / tvær | twai / twos | * twajina | * dwou |

| three | dri | dräi | thri | three | three | thria | þri | three | þrír | þreis | * þrejes | * trejes |

| four | fior | four | viuwar | four | four | fi (u) was | feower | four | fjórir | fidwor | * feđwōr | * kwetwor |

| five | fimf | fënnef | vīf | vijf | vyf | fif | fif | five | fim (m) | fimf | * femf (e) | * penqwe |

| six | see | six | see | zes | ses | see | siex | six | sex | saihs | * seχs | * sec |

| seven | sibun | siwen | sivon | zeven | sewe | sibun | seofon | seven | sjau | sibun | * sebun | * septṃ |

| eight | ahto | aight | ahto | eight | agt | ahto | eahta | eight | átta | ahtau | * aχtau | * oktou |

| nine | nium | ning, néng | nigun | negen | nega | nigun | nigon | nine | níu | ni'un | * newun | * (e) newṇ |

| ten | zehan | zing, zéng | tēn | tien | tien | tehan | tien | th | tíu | taihun | * teχun | * dekṃ |

| hundred | hunt | hoots | dog | hond-earth | hond-earth | dog | dog-red | dog-red | dog wheel | dog | * χunđa | * kṃtóm |

The source of these tables is the web link “Germanic word equations”, which in turn was compiled on the basis of several etymological dictionaries, including Kluge 2002, Onions 1966, Philippa 2009, and Pokorny 1959.

In all Germanic languages 13 is the first composite number (e.g. English thirteen ), the numbers 11 and 12 have their own names (e.g. English eleven and twelve ).

Germanic sound shift

The Germanic languages differ from other Indo-European languages by a characteristic, precisely the “Germanic” consonant shift, which in German studies is differentiated as a “first” from a subsequent “second” sound shift. The following table provides word equations that prove this transition from the Indo-European to the corresponding Proto-European consonants. Since the High German parallels are also given, the table also shows the second sound shift from (Ur-) Germanic to High German. Reconstructed Proto-European and Indo-European forms are marked with *, corresponding consonants are highlighted in bold.

| No | * Idg. | Latin | Greek | * German. | English | Dutch | German |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | * p əter | p ater |

π ατήρ p atḗr |

* f ađer | f ather | v vein | V ater |

| 2 | * bhra t ar | fra t he | phra t ér | * brō þ er | bro th he | broe d he | Bru d he |

| 3 | * k earth | c ord- | k ard- | * χ ertōn | h eart | h art | H ore |

| 4th | * dheu b | . | . | * eng p | dee p | the p | tie f |

| 5a | * e d - | e d - | e d - | * i t ana | ea t | e t en | e ss s |

| 5b | * se d - | se d - | . | * si t ana | si t | zi tt s | si tz en |

| 6th | * e g o | e g o | e g o | * e k | I / aengl : i c | i k | i ch |

| 7th | * bh he | f ER- | ph er | * b airana | b ear | b aren | overall b eras |

| 8th | * u dh ar | u b er | oũ th ar | * u d ar | u dd he | uier / mnl: uy d er | Eu t he |

| 9 | * we gh - | ve h - | . | * we g a- | white gh | we g s | like g en |

While z. B. Latin and Greek largely retain the “Indo-European” consonants, Germanic experiences a phonetic change in tenues / p, t, k /, Mediae / b, d, g / and Mediae-Aspiratae / bh, ie, gh /. English and Low German have preserved these “Germanic” consonants to this day, but when switching to High German there is a second shift in the sound of this group of consonants. Overall, the following sound laws result:

Germanic and High German sound shift

| No | Indo-term. → | Germanic → | Standard German |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | p → | f → | f |

| 2 | t → | þ (th) → | d |

| 3 | k → | h (ch) → | H |

| 4th | b → | p → | ff / pf |

| 5 | d → | t → | ss / tz |

| 6th | g → | k → | hh / ch |

| 7th | bh → | b → | b ( alem./bair. p) |

| 8th | ie → | d → | t |

| 9 | gh → | g → | g ( bair. k) |

Notes on the history of language

Proto-European and its splits

Some researchers suggest that Proto -European formed a dialect group within the West Indo-European languages with the precursors of the Baltic and Slavic languages . This assumption is supported not least by a recent lexicostatistical work. These pre-forms of Germanic could already be found in the late 3rd and early 2nd millennium BC. BC, according to their geographical location, occupied an intermediate position between the presumed language groups Italo-Celtic in the south-west and Baltic-Slavic in the south-east.

Proto-European then broke away from this group, according to which it shows clear interactions with early Finnish languages .

Regarding a so-called Germanic “original home”, the Onomast Jürgen Udolph makes the argument that Germanic place and waterfront names can be found with a focus on the wider Harz region. However, this observation basically only proves a Germanic settlement that has not been disturbed since the naming, not its time frame. On the other hand, archaeological finds based on similar, unbroken traditions in the area between the Harz region proposed by Udolph and southern Scandinavia since around the 12th century BC provide a time frame. Chr.

The Proto-Germanic language (also “Urgermanisch” or “Common Germanic”) could be largely reconstructed through linguistic comparisons. This developed preform is said to be up to around 100 BC. Chr., In the so-called common Germanic language period have remained relatively uniform. As a peculiarity it is noticeable that the Germanic uses some Indo-European hereditary words quite idiosyncratically (example: see = "[with the eyes] to follow", cf. Latin sequi ). According to Euler (2009), the extinct East Germanic, passed down almost exclusively through Gothic , was the first language to split off. In the 1st century. AD. Would have then the West Germanic of the North Germanic separate languages.

Vocabulary, loanwords

It was hypothesized that the Proto -Germanic vocabulary should have contained a number of loan words of non-Germanic origin. Striking z. B. Borrowings in the field of shipbuilding and navigation from a previously unknown substrate language , probably in the western Baltic region. This Germanic substratum hypothesis has meanwhile been strongly disputed. In contrast, loans in the area of social organization are mainly attributed to Celtic influence . These observations suggest the emergence of Germanic as an immigrant language. Valuable references to both the Germanic sound forms and prehistoric neighbors are still given today in the Baltic-Finnish languages borrowed from Germanic, such as B. Finnish kuningas (king) from Germanic: * kuningaz , rengas (ring) from Germanic: * hrengaz (/ z / stands for voiced / s /).

items

Germanic originally knew neither the definite nor the indefinite article , as did Latin and most of the Slavic and Baltic languages. West Germanic then formed the definite articles “der”, “die” and “das” from the demonstrative pronouns . The indefinite articles were formed in the West Germanic and in most of the North Germanic languages (as in the Romance languages) from the numeral for "1". Modern Icelandic did not develop an indefinite article.

See also

literature

General

- Wayne Harbert: The Germanic Languages . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-01511-0 .

- Claus Jürgen Hutterer : The Germanic languages. Your story in outline . 4th edition. VMA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-928127-57-8 .

- Ekkehard König and Johan van der Auwera (eds.): The Germanic Languages . Routledge, London / New York 1994, ISBN 0-415-05768-X .

- Werner König and Hans-Joachim Paul: dtv Atlas German Language . 15th edition. dtv, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-423-03025-9 .

- Orrin W. Robinson: Old English and Its Closest Relatives. A Survey of the Earliest Germanic Languages . Stanford University Press, Stanford (Calif) 1992, ISBN 0-8047-1454-1 .

Etymological dictionaries

- Friedrich Kluge : Etymological dictionary of the German language. Edited by Elmar Seebold . 25th, revised and expanded edition. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-022364-4 .

- CT Onions (Ed.): The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1966.

- Marlies Philippa u. a .: Etymologically woordenboek van het Nederlands. 4 volumes. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2003-2009, ISBN 978-90-8964-184-7 .

- Julius Pokorny : Indo-European etymological dictionary . Francke Verlag, Bern / Munich 1959.

Web links

- Ernst Kausen, The Classification of Indo-European and its Branches (DOC; 220 kB)

- Ernst Kausen, Germanic word equations (DOC; 40 kB)

- Germanic family tree (examples of obsolete models)

- Germanic-German language history

- Studies on the oldest Germanic alphabets , 1898, e-book of the University Library Vienna ( e-books on demand )

Remarks

- ^ Rudolf Wachter: Indo-European or Indo-European? University of Basel, August 25, 1997, accessed June 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Quoted from Astrid Adler et al .: STATUS UND GEBRAUCH DES NIEDERDEUTSCHEN 2016, first results of a representative survey , p. 15, in: Institute for German Language , 2016, accessed on May 9, 2020.

- ↑ Quoted from Astrid Adler et al .: STATUS UND GEBRAUCH DES NIEDERDEUTSCHEN 2016, first results of a representative survey , p. 15, in: Institute for German Language , 2016, accessed on May 9, 2020.

- ↑ Ernst Kausen: The classification of the Indo-European and its branches . ( MS Word ; 220 kB)

- ↑ Diagram is based on: Stefan Sonderegger: Old High German Language. In: Brief outline of Germanic philology up to 1500. Ed. By Ludwig Erich Schmitt. Volume 1: History of Language. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1970, p. 289.

- ↑ Paulo Ramat: Introduction to Germanic. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-484-10411-2 , p. 6.

- ↑ Paulo Ramat: Introduction to Germanic. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-484-10411-2 , p. 5 f.

- ↑ Paulo Ramat: Introduction to Germanic. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-484-10411-2 , p. 6.

- ^ Steffen Krogh: The position of Old Saxon in the context of the Germanic languages. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, ISBN 978-3-525-20344-6 , 1996, p. 136.

- ↑ Paulo Ramat: Introduction to Germanic. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-484-10411-2 , p. 7.

- ^ Helmut Kuhn: To the structure of the Germanic languages. In: Journal for German Antiquity and German Literature 86, 1955, pp. 1-47.

- ^ Stefan Sonderegger: Stefan Sonderegger : Basics of German language history. Diachrony of the language system. Volume 1: Introduction, Genealogy, Constants. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1979 (reprint 2011), pp. 118–128.

- ^ Fausto Cercignani : The Elaboration of the Gothic Alphabet and Orthography. In Indo-European Research. 93, 1988, pp. 168-185.

- ↑ Svensk etymologisk ordbok (1922), p. 503

- ↑ today “lighthouse”, historically see Svensk etymologisk ordbok (1922) p. 164 3. fyr … fyr och flamma (“fire and flame”)

- ↑ Kluge - Etymological Dictionary of the German Language, 24th edition, p. 679: Pflug - testimony and evidence are contradictory. Longobard plovum ; Pliny mentioned an improved plow called plaumorātum in Gaulish Raetia .

- ↑ M. Philippa, F. Debrabandere, A. Quak, T. Schoonheim en N. van der Sijs: Etymologische Woordenboek van het Nederlands, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, ISBN 978-90-6648-312-5 , 2009.

- ↑ Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand: Words and things: To the meaning of a method for the early Middle Ages research. The plow and its designations in: Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand: Words and Things in the Light of Designation Research, Walter de Gruyter, 2019, pp. 1–41.

- ^ Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München: You and Thou: Loss of a politeness marking? (PDF)

- ↑ Ernst Kausen: Germanic word equations . ( MS Word ; 40 kB)

- ↑ Hans J. Holm (2008): The Distribution of Data in Word Lists and its Impact on the Subgrouping of Languages. link.springer.com In: Christine Preisach, Hans Burkhardt, Lars Schmidt-Thieme, Reinhold Decker (Eds.): Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications. Proc. of the 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society (GfKl), University of Freiburg, March 7–9, 2007. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg / Berlin.

- ↑ Elke Hentschel, Harald Weydt: Handbuch der Deutschen Grammatik: 4th, completely revised edition, Walter de Gruyter, 2013, p. 208.

- ↑ Thorsten Roelcke: Variation Typologie / Variation Typology: Ein Sprachtypologisches Handbuch der European languages in past and present / A Typological Handbook of European Languages, Walter de Gruyter, 2008, p. 173.