Old high German language

| Old High German | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

south of the so-called " Benrath Line " | |

| speaker | since about 1050 none | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

goh |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

goh |

|

As Old High German or Old High German (abbreviated Ahd. ) Is the oldest written form of German that has been used between 750 and 1050. Your previous language level , Pre-Old High German , is only documented by a few runic inscriptions and proper names in Latin texts.

The word “German” appears for the first time in a document from the year 786 in the Middle Latin form theodiscus . In a church assembly in England the resolutions “ tam latine quam theodisce ” were read out, that is “both Latin and in the vernacular” (this vernacular was, of course, Old English ). The Old High German form of the word is only documented much later: In the copy of an ancient language textbook in Latin, probably made in the second quarter of the 9th century, there was an entry of a monk who apparently did not use the Latin word galeola (crockery in the shape of a helmet) understood. He must have asked a confrere the meaning of this word and added the meaning in the language of the people. For his note he used the Old High German early form " diutisce gellit " ("in German 'bowl'").

Territorial delimitation and division

Legend:

Old High German is not a uniform language, as the term suggests, but the name for a group of West Germanic languages that were spoken south of the so-called " Benrath Line " (which today runs from Düsseldorf - Benrath approximately in a west-east direction). These dialects differ from the other West Germanic languages by the implementation of the second (or standard German) sound shift . The dialects north of the “Benrath Line”, that is, in the area of the north German lowlands and in the area of today's Netherlands , did not carry out the second sound shift. To distinguish them from Old High German, these dialects are grouped under the name Old Saxon (also: Old Low German ). Middle and New Low German developed from Old Saxon . However, the Old Low Franconian , from which today's Dutch later emerged, did not take part in the second sound shift, which means that this part of Franconian does not belong to Old High German.

Since Old High German was a group of closely related dialects and there was no uniform written language in the early Middle Ages , the text that has been handed down can be assigned to the individual Old High German languages, so that one often speaks more appropriately of (Old) South Rhine Franconian , Old Bavarian , Old Alemannic , etc. These West Germanic varieties with the second sound shift, however, show a different proximity to one another, which is the reason for the later differences between Upper , Middle and Low German . For example, Stefan Sonderegger writes that with regard to the spatial-linguistic-geographical structure, Old High German should be understood as follows:

"The oldest stages of the Middle and High Franconian, d. H. West Central German dialects one hand and the Alemannic and Bavarian, ie Upper German dialects on the other, and. in time ahd the first time tangible, but at the same time already dying language level of Lombard in northern Italy . The Ahd remains clearly separated. from the Old Saxon in the subsequent north, while a staggered transition can be determined to the Old Dutch-Old Lower Franconian and West Franconian in the northwest and west . "

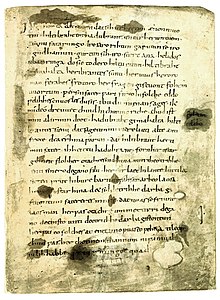

Old high German traditions and written form

The Latin alphabet was adopted in Old High German for the German language. On the one hand, there were surpluses of graphemes such as <v> and <f> and, on the other hand, “uncovered” German phonemes such as diphthongs , affricates (such as / pf /, / ts /, / tʃ /), and consonants such as / ç / < ch> and / ʃ / <sch>, which did not exist in Latin. In Old High German, the grapheme <f> was mainly used for the phoneme / f /, so that here it is fihu (cattle), filu (a lot), fior (four), firwizan (to refer) and folch (people), while in Middle High German The grapheme <v> was predominantly used for the same phoneme, but here it is called vinsternis (darkness), vrouwe (woman), vriunt (friend) and vinden (to find). These uncertainties, which still affect spellings like "Vogel" or "Vogt", can be traced back to the grapheme excesses described in Latin.

The oldest surviving Old High German text is the Abrogans , a Latin-Old High German glossary. In general, the Old High German tradition consists largely of spiritual texts ( prayers , baptismal vows, Bible translation ); only a few secular poems ( Hildebrandslied , Ludwigslied ) or other language certificates (inscriptions, magic spells ) are found. The Würzburg mark description or the Strasbourg oath of 842 belong to public law, but these are only passed down in the form of a copy by a Romance-speaking copyist from the 10th and 11th centuries.

The so-called " Old High German Tatian " is a translation of the Gospel Harmony by the Syrian-Christian apologist Tatianus (2nd century) into Old High German. He is bilingual (Latin-German); the only surviving manuscript is now in St. Gallen. Alongside the Old High German Isidor, the Old High German Tatian is the second major translation achievement from the time of Charlemagne.

In connection with the political situation, the written form in general and the production of German-language texts in particular decreased in the 10th century; a renewed use of German-language writing and literature can be observed from around 1050. Since the written tradition of the 11th century differs significantly from the older tradition in phonetic terms, the language is called Middle High German from around 1050 onwards . Notker's death in St. Gallen 1022 is often defined as the end point of Old High German text production .

Characteristics of language and grammar

Old High German is a synthetic language .

umlaut

The Old High German primary umlaut is typical of Old High German and important for the understanding of certain forms in later language levels of German (such as the weak verbs that are written back ) . The sounds / i / and / j / in the following syllable cause / a / to be changed to / e /.

Final syllables

Characteristic of the Old High German language are the endings, which are still full of vowels (see Latin ).

| Old High German | New High German |

|---|---|

| mahhôn | do |

| day | Days |

| demo | the |

| perga | mountains |

The weakening of the final syllables in Middle High German from 1050 is the main criterion for the delimitation of the two language levels.

Nouns

The noun has four cases (nominative, genitive, dative, accusative) and remnants of a fifth ( instrumental ) are still present. A distinction is made between a strong (vowelic) and a weak (consonantic) declination .

| number | case | masculine | feminine | neutral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Nom. | han o | tongue a | hërz a |

| Acc. | han on, -un | zung ūn | hërz a | |

| Date | han en, -in | zung ūn | hërz en, -in | |

| Gene. | ||||

| Plural | Nom. | han on, -un | zung ūn | hërz un, -on |

| Acc. | ||||

| Date | han ōm, -ōn | zung ōm, -ōn | hërz ōm, -ōn | |

| Gene. | han ōno | zung ōno | hërz ōno | |

| meaning | Rooster | tongue | heart | |

Further examples of masculine nouns are stërno (star), namo (name), forasago (prophet), for feminine nouns quëna (woman), sunna (sun) and for neutral ouga (eye), ōra (ear).

Personal pronouns

| number | person | genus | Nominative | accusative | dative | Genitive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. | ih | mih | me | mīn | |

| 2. | you | dih | to you | dīn | ||

| 3. | Masculine | (h) he | inan, in | imu, imo | (sīn) | |

| Feminine | siu; sī, si | sia | iro | ira, iru | ||

| neuter | iz | imu, imo | it is | |||

| Plural | 1. | we | unsih | us | our | |

| 2. | ir | iuwih | iu | iuwēr | ||

| 3. | Masculine | she | iro | in, in | ||

| Feminine | sio | |||||

| neuter | siu | |||||

- The form of politeness corresponds to the 2nd person plural.

- Next to our and iuwer there are also unsar and iuwar , and next to iuwar and iuwih there are also iwar and iwih .

- In Otfrid also the genitive dual 1st person finds: Unker (or uncher , as Unkar or unchar shown).

Demonstrative pronouns

In the Old High German period, however, one still speaks of the demonstrative pronoun , because the specific article as a grammatical phenomenon did not develop from the demonstrative pronoun until late Old High German.

| case | Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | neutrally | Female | male | neutrally | Female | |

| Nominative | of the | daȥ | diu | dē, dea, dia, die | diu, (dei?) | deo, dio |

| accusative | the | dea, dia (the) | ||||

| dative | dëmu, -o | dëru, -o | the the | |||

| Genitive | of | dëra, (dëru, -o) | dëru | dëra | ||

Nominative and accusative are quite arbitrary in the plural and differ from dialect to dialect, so that an explicit separation of which of these forms expressly describes the accusative and which the nominative is not possible. In addition, on the basis of this list, one can already see a slow collapse of the various forms. While there are still many quite irregular forms in the nominative and accusative plural, the dative and genitive, both in the singular and in the plural, are relatively regular.

Verbs

A distinction is also made between strong (vowel) and weak conjugation in verbs. The number of weak verbs was always higher than that of strong verbs, but the second group was significantly more extensive in Old High German than it is today. In addition to these two groups, there are the past tense , verbs that have a present tense meaning with their original past tense form.

Strong verbs

In the case of strong verbs, in Old High German there is a change in the vowel in the basic morphem , which carries the lexical meaning of the word. The inflection (inflection) of the words is indicated by inflectional morphemes (endings). There are seven different ablaut series in Old High German, the seventh not being based on an ablaut , but rather on reduplication .

| Ablaut series | infinitive | Present | preterite | Plural | participle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. | a | ī + consonant (neither h nor w ) | ī | egg | i | i |

| I. | b | ī + h or w | ē | |||

| II. | a | io + consonant (neither h nor dental ) | iu | ou | u | O |

| II. | b | io + h or Dental | O | |||

| III. | a | i + nasal or consonant | i | a | u | u |

| III. | b | e + liquid or consonant | O | |||

| IV. | e + Nasal or Liquid | i | a | - | O | |

| V. | e + consonant | i | a | - | e | |

| VI. | a + consonant | a | uo | uo | a | |

| VII. | ā, a, ei, ou, uo or ō | ie | ie | like Inf. | ||

Examples in reconstructed and unified Old High German:

- Ablaut series Ia

- r ī tan - r ī tu - r ei t - r i tun - gir i tan (nhd. riding, driving)

- Ablaut series Ib

- z ī han - z ī hu - z ē h - z i gun - giz i gan (nhd. accuse, draw)

- Ablaut series II.a

- b io gan - b iu gu - b ou g - b u gun - gib o gan (nhd. bend)

- Ablaut series II.b

- b io tan - b iu tu - b ō t - b u tun - gib o tan (nhd. offer)

- Ablaut series III.a.

- b i ntan - b i ntu - b a nt - b u ntun - gib u ntan (nhd. to bind)

- Ablaut series III.b.

- w e rfan - w i rfu - w a rf - w u rfun - giw o rfan (nhd. throw)

- Ablaut series IV.

- n e man - n i mu - n a m - n ā mun - gin o man (nhd. to take)

- Ablaut series V.

- g e ban - g i bu - g a b - g ā bun - gig e ban (nhd. to give)

- Ablaut series VI.

- f a ran - f a ru - f uo r - f uo run - gif a ran (nhd. drive)

- Ablaut series VII.

- r ā tan - r ā tu - r ie t - r ie tun - gir ā tan (nhd. guess)

| mode | number | person | pronoun | Present | preterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indicative | Singular | 1. | ih | throw u | threw |

| 2. | you | throw is / throw is | litter i | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | throw it | threw | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | throw emēs (throw ēn ) | throw over (throw over ) | |

| 2. | ir | throw et | litter ut | ||

| 3. | you, siu | throw ent | throw un | ||

| conjunctive | Singular | 1. | ih | throw e | litter i |

| 2. | you | throw ēs / throw ēst | wurf īs / wurf īst | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | throw e | litter i | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | werf ēm (throw emēs ) | litter īm (litter īmēs ) | |

| 2. | ir | throw eT | throw īt | ||

| 3. | you, siu | throw ēn | throw īn | ||

| imperative | Singular | 2. | throw | ||

| Plural | throw et | ||||

| participle | throw anti / throw enti | gi worf at | |||

Example: werfan - werfu - threw - wurfun - giworfan (nhd. Throw) according to the ablaut series III. b

Weak verbs

The weak verbs of Old High German can be morphologically and semantically divided into three groups via their endings:

Verbs with the ending -jan- with a causative meaning (to do something, to bring about) are elementary for understanding the weak verbs with back umlaut that are very common in Middle High German and are still partially present today , as the / j / in the ending is the primary umlaut described above effected in the present tense.

| mode | number | person | pronoun | Present | preterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indicative | Singular | 1. | ih | cell u | cell it a |

| 2. | you | cell is | cell it os | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | cell it | cell it a | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | cell umēs | cell it around | |

| 2. | ir | zell et | cell it ut | ||

| 3. | you, siu | cell ent | cell it un | ||

| conjunctive | Singular | 1. | ih | zel e | zel it i |

| 2. | you | cell ēst | zel it īs | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | zel e | zel it i | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | zel ēm | zel it īm | |

| 2. | ir | zel ēt | zel it īt | ||

| 3. | you, siu | zel ēn | zel it īn | ||

| imperative | Singular | 2. | zel | ||

| Plural | zell et |

| mode | number | person | pronoun | Present | preterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indicative | Singular | 1. | ih | mahh om | mahh ot a |

| 2. | you | mahh os | mahh ot os | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | mahh ot | mahh ot a | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | mahh omēs | mahh ot um | |

| 2. | ir | mahh ot | mahh ot ut | ||

| 3. | you, siu | mahh ont | mahh ot un | ||

| conjunctive | Singular | 1. | ih | mahh o | mahh ot i |

| 2. | you | mahh о̄s | mahh ot īs | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | mahh o | mahh ot i | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | mahh о̄m | mahh ot īm | |

| 2. | ir | mahh о̄t | mahh ot īt | ||

| 3. | you, siu | mahh о̄n | mahh ot īn | ||

| imperative | Singular | 2. | mahh o | ||

| Plural | mahh ot |

| mode | number | person | pronoun | Present | preterite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indicative | Singular | 1. | ih | tell em | say et a |

| 2. | you | say it | say et os | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | say et | say et a | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | say emes | Tell et order | |

| 2. | ir | say et | say et ut | ||

| 3. | you, siu | say ent | Tell et un | ||

| conjunctive | Singular | 1. | ih | say e | say et i |

| 2. | you | say ēs | say et īs | ||

| 3. | he, siu, iz | say e | say et i | ||

| Plural | 1. | we | say ēm | say et im | |

| 2. | ir | say ēt | say et īt | ||

| 3. | you, siu | say ēn | say et īn | ||

| imperative | Singular | 2. | say e | ||

| Plural | say et |

Special verbs

The Old High German verb sīn ' to be' is referred to as the verb noun substantivum because it can stand on its own and describes the existence of something. It is one of the root verbs that have no connecting vowel between stem and inflection morphemes. These verbs are also known as athematic (without connective or subject vowels). The special thing about sīn is that its paradigm is suppletive, i.e. is formed from different verb stems ( idg. * H₁es- 'exist', * bʰueh₂- 'grow, flourish' and * h₂ues- 'linger, live, stay overnight'). In the present subjunctive there is still the sīn, which goes back to * h₁es- (the indicative forms starting with b , on the other hand, go back to * bʰueh₂- ), but in the past tense it is given by the strong verb wesan (nhd. Was , would ; see also nhd. Essence ), which is formed after the fifth ablaut row.

| number | person | pronoun | indicative | conjunctive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1. | ih | bim, am | sī |

| 2. | you | are | sīs, sīst | |

| 3. | he, siu, ez | is | sī | |

| Plural | 1. | we | birum, birun | sīn |

| 2. | ir | birut | sīt | |

| 3. | she, sio, siu | sint | sīn |

Tense

In Germanic there were only two tenses: the past tense for the past and the present tense for the non-past (present, future). With the onset of writing and translations from Latin into German, the development of German equivalents for Latin tenses such as perfect , past perfect , future I and future II in Old High German began. At least approaches to having and being perfect can already be made out in Old High German. The development was continued in Middle High German .

pronunciation

The reconstruction of the pronunciation of Old High German is based on a comparison of the traditional texts with the pronunciation of today's German, German dialects and related languages. This results in the following pronunciation rules:

- Vowels are always to be read briefly, unless they are expressly indicated as long vowels by an overline or circumflex . Only in New High German are vowels spoken long in open syllables .

- The diphthongs ei, ou, uo, ua, ie, ia, io and iu are spoken as diphthongs and are emphasized on the first component. It should be noted that the letter <v> sometimes has the sound value u.

- The stress is always on the root, even if any of the following syllables contain a long vowel.

- The sound values of most consonant letters correspond to those of today's German. Since the final hardening only took place in Middle High German, <b>, <d> and <g> are spoken voiced differently than in modern German .

- The graph <th> was spoken in early Old High German as a voiced dental fricative [ð] (like <th> in English the ), but from around 830 onwards one can read [d].

- <c> - just like the more frequently occurring <k> - is spoken as [k], even when it appears in connection with <s> - i.e. as <sc>.

- <z> is ambiguous and partly stands for [ts], partly for the voiceless [s].

- <h> is initially spoken as [h], internally and finally as [x].

- <st> is also spoken in the wording [st] (not like today [ʃt]).

- <ng> is spoken [ng] (not [ŋ]).

- <qu> is spoken like in today's German [kv].

- <uu> (which is often transcribed as <w>) is pronounced like the English half-vowel [ w ] ( water ).

See also

literature

- Eberhard Gottlieb Graff : Old high German vocabulary or dictionary of the old high German language. I-VI. Berlin 1834–1842, reprint Hildesheim 1963.

- Hans Ferdinand Massmann : Complete alphabetical index to the old high German linguistic treasure of EG Graff. Berlin 1846, reprint Hildesheim 1963.

- Rolf Bergmann u. a. (Ed.): Old High German.

- Grammar. Glosses. Texts. Winter, Heidelberg 1987, ISBN 3-533-03877-7 .

- Words and names. Research history. Winter, Heidelberg 1987, ISBN 3-533-03940-4 .

- Wilhelm Braune : Old High German grammar. Halle / Saale 1886; 3rd edition ibid. 1925 (last edition; continued under Karl Helm, Walther Mitzka , Hans Eggers and Ingo Reiffenstein ) = collection of short grammars of Germanic dialects A, 5; newer edition z. B. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-484-10861-4 .

- Axel Lindqvist: Studies on word formation and choice of words in Old High German with special regard to the nominia actionis. In: [Paul and Braunes] contributions to the history of the German language and literature. Volume 60, 1936, pp. 1-132.

- Eckhard Meineke, Judith Schwerdt: Introduction to Old High German (= UTB 2167). Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2001, ISBN 3-8252-2167-9 .

- Horst Dieter Schlosser : Old High German Literature. 2nd edition, Berlin 2004.

- Richard Schrodt : Old High German Grammar II. Syntax. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-484-10862-2 .

- Rudolf Schützeichel : Old High German Dictionary. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1969; newer edition 1995, ISBN 3-484-10636-0 .

- Rudolf Schützeichel (Ed.): Old High German and Old Saxon Gloss Vocabulary. Edited with the participation of numerous scientists from home and abroad and on behalf of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. 12 volumes, Tübingen 2004.

- Stefan Sonderegger : Old High German Language and Literature. An introduction to the oldest German. Presentation and grammar. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin [a. a.] 1987, ISBN 3-11-004559-1 .

- Bergmann, Pauly, Moulin: Old and Middle High German. Workbook on the grammar of the older German language levels and on the history of the German language. 7th edition, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-20836-6 .

- Jochen Splett: Old High German Dictionary. Analysis of the word family structures of Old High German, at the same time laying the groundwork for a future structural history of the German vocabulary, I.1 – II. Berlin / New York 1993, ISBN 3-11-012462-9 .

- Taylor Starck, John C. Wells : Old High German Glossary Dictionary (including the glossary index started by Taylor Starck). Heidelberg (1972–) 1990.

- Elias Steinmeyer , Eduard Sievers : The old high German glosses. IV, Berlin 1879-1922; Reprinted Dublin and Zurich 1969.

- Rosemarie Lühr : The Beginnings of Old High German. In: NOWELE 66, 1 (2013), pp. 101–125. ( Full text )

- Andreas Nievergelt: Old High German in runic script. Cryptographic vernacular pen glosses . 2nd edition, Stuttgart 2018, ISBN 978-3-777-62640-6 .

Web links

- Online dictionary , Wikiling: Old High German (and other ancient languages)

- Old high German dictionary

- Old High German in the World Loanword Database

- Old High German in the International Dictionary Series. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014 ; accessed on March 17, 2016 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jochen A. Bär: A short history of the German language .

- ^ Map based on: Meineke, Eckhard and Schwerdt, Judith, Introduction to Old High German, Paderborn / Zurich 2001, p. 209.

- ↑ Stefan Sonderegger: Old High German Language and Literature , page 4

- ↑ Oscar Schade: Old German Dictionary . Halle, 1866, page 664.

- ↑ Adalbert Jeitteles: KA Hahns Old High German Grammar along with some reading pieces and a glossary 3rd edition, Prague, 1870, page 36 f.

- ↑ Otfrid von Weißenburg, Gospel Book, Book III, Chapter 22, Verse 32

- ↑ Adalbert Jeitteles: KA Hahn's Old High German Grammar along with some reading pieces and a glossary 3rd edition. Prague 1870, page 37.

- ↑ Ludwig M. Eichinger : Inflection in the noun phrase. In: Dependenz und Valenz. 2nd half volume, Ed .: Vilmos Ágel u. a. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2006, p. 1059.

- ^ Rolf Bergmann, Claudine Moulin, Nikolaus Ruge: Old and Middle High German . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8252-3534-5 , pp. 171ff.

- ^ Rolf Bergmann, Claudine Moulin, Nikolaus Ruge: Old and Middle High German - Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, p. 173.