Old Bavarian

Old Bavarian is the language of the earliest texts from the Old High German period (8th century to around 1050), which were written in the then tribal duchy of Baiern and by scribes from this area. Old Bavarian was the language of the Bavarians before a supra-regional German literary language ( Middle High German ) emerged in the High Middle Ages . No written sources of the language have survived from the time of the Bavarian ethnogenesis in the 6th century, the first old Bavarian texts date from the end of the 8th century. All statements referring to the time before are based on linguistic reconstructions.

The term Old Bavarian is to be distinguished from the modern dialects in Old Bavaria , whereby Old Bavarian was a preliminary stage of all recent Bavarian dialects , both in today's Old Bavaria as well as in Austria and South Tyrol.

Origin of the Old Bavarian

When the Roman troops led by Julius Caesar in 58 BC BC , the governor of the Roman province of Southern Gaul, conquered the rest of the Gallic territories as well, the Roman Empire began to expand further east. Their territorial consolidation progressed under Augustus . During the centuries-long rule of the Romans resulted from immigration and settlement and improved living conditions a higher population growth , and by the Constitutio Antoniniana the Emperor Caracalla all free inhabitants of the from the year 212 Roman provinces the Roman citizenship was granted - even in Rhaetia and Noricum . These romanized provincial citizens are called provincials . The two relics referring to Boier in the country also date from the Roman period : a Roman military diploma , which was awarded in 107 AD to the soldier Mogetissa of a Hispanic cavalry unit (a so-called Ala ) in Raetia, whose father Comatullus a Boio and a shard of pottery with Boio carved into it. The influence of Latin increased steadily until there were two decisive changes east of the Rhine in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD. Germanic tribes united to form large tribes and so the pressure of different tribes on the Roman borders, language and culture increased more and more.

Old Bavarian originated in the 6th century in the region north of the Alps and south of the Danube, in the context of a Roman culture. In the year 488 AD Odoacer , the ruler of Roman Italy, ordered the remaining Roman troops and the Roman civilian population on the Danube to withdraw to Italy in order to pool the remaining forces against the Ostrogoths . As a result, the Danube border was no longer defended by the Romans and the land south of it was abandoned. After the end of Roman rule on the Danube, various Germanic groups crossed the Danube and settled on the land that was previously part of the Roman provinces of Noricum and Raetia Secunda.

Various Elbe Germanic groups such as Lombards , Marcomanni and Alemanni , as well as the remaining Celto-Roman population and smaller groups of East Germanic tribes and Slavs have merged in this area into a new ethnic unit, the Bavarians. The language of the Bavarians therefore also bears traces of this heterogeneous origin and has a Latin and a Slavic substratum , as well as small East Germanic language influences.

Only later did the old Bavarian language area also expand eastward over the Traun in Upper Austria and then over the Enns into today's Lower Austria, as well as south-east into today's Styria and Carinthia . Before that, Slavic-speaking people lived there who only switched to Bavarian a few generations later, even after the conquest. In the south-east of Carinthia there is still the autochthonous Slovene-speaking minority ( Carinthian Slovenes ).

In Salzburg and Tyrol, on the other hand, the Romansh-speaking population was more numerous, which has led to a stronger Romansh substrate in this region. Up until the High Middle Ages there were still Romansh language islands there and today's Ladin and Rhaeto-Romansh are remnants of these Alpine novels.

In the north, in today's Upper Palatinate, the Old Bavarian bordered on the Old Upper Franconian, which meant that there was also a Franconian influence there. Later, after the Bavarian tribal duchy became part of the Franconian Empire in 788, there was a Franconian influence in the entire Old Bavarian language area, which is called the Franconian Superstrat . Franconian aristocrats were also assigned fiefs on the outermost edge of the Bavarian duchy, in present-day Carinthia, Styria and Burgenland, which means that Franconian influences themselves continued to have an effect up to that point.

Characteristics of the Old Bavarian

Old Bavarian is a West Germanic language which, at the time of the first written sources, had already fully completed the second sound shift . This sound shift has already been documented in Longobard sources from northern Italy, which is why it is assumed that it spread to the north from there. The Lombard and Altbairische were probably also very similar, in view of the few sources Lombard a detailed statement as to appear almost impossible. At this time there were also still few differences to the Alt Alemannic . Only in the 12th century did Alemannic and Bavarian drift apart due to different sound developments ( diphthongization ).

Within the West Germanic languages, Old Bavarian is part of the Elbe Germanic group and also has smaller East Germanic influences, such as the Bavarian weekdays (Erietag, Pentecost) , certain lexical peculiarities ( e.g. Dult ) and the conservation of the dual forms (singular-dual-plural) . Whether the Bavarian dual goes back to Gothic influence or was adopted by the Rugians or Skiren , or whether it represents an independent regional peculiarity, is disputed.

Another difference to other West Germanic idioms or Old High German varieties of this time is the Romance and Slavic substratum in Old Bavarian, whereby most of the Slavic-derived words in today's Bavarian dialects were only taken up as astrate much later .

The Latin substrate, on the other hand, is already clearly recognizable in Old Bavarian not only in the lexical area, but also in the grammar. Latin relic words that do not appear in more northern idioms are for example "Ribisl" (Latin: ribes ), "Most" (Latin: vinum mustum ), "Radi" (Latin: radix ). Other Romance words have followed all of the later sound developments and must therefore have already existed at this time. Or the sentence

* Mi bringt mi koana aus’n heisl. dt. „Mich bringt (mich) keiner aus dem Häuschen.“

with regard to the position of the sentence and the use of the ( Romance ) personal pronoun as well as its clitic double structures could be directly inserted into the

* Spanische: Te lo diré a ti oder in das * Französische: Moi je le dirai à toi

be transmitted.

Phonetic peculiarities

In the phonetic area, Old Bavarian has the following peculiarities compared to other Old High German varieties:

- Shifting of the voiceless plosives (tenues) has been fully implemented since the 8th and 9th centuries

- Media shift was largely carried out in the 8th and 9th centuries (typical of Old Bavarian are the Fortis consonants p / t / k instead of b / d / g in the initial sound)

- the Germanic <Þ> (th) became a <d> in the 8th century

- the Germanic long ō is preserved until the 9th century, often written as <oo>

- the dull reduction vowel <e> in Old High German ancillary syllables is usually written as <a> in Old Bavarian

Lexical peculiarities

Some words and even legal and religious terms differ in Old Bavarian from other Old High German idioms, with a difference between Bavarian and Alemannic on the one hand and the Franconian varieties on the other. Lexical examples are:

- Court, judgment: suona (Alemannic, Bavarian); tuom (Franconian)

- complaints: klagōn (Alemannic, Bavarian); wuofen (Franconian)

- Memory, souvenir: gihuct (Alemannic, Bavarian); gimunt (Franconian)

- to be happy: to be happy (Alemannic, Bavarian); gifëhan (Franconian)

- humble: deomuoti (Alemannic, Bavarian); ōdmuoti (Franconian)

- holy: wīh (Alemannic, Bavarian); Heilag (Franconian)

- Spirit: ātum (Alemannic, Bavarian); Geist (Franconian)

Part of Old High German

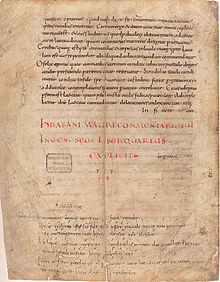

In linguistics, all West Germanic languages or idioms of this time (approx. 750 to 1050), in which the second sound shift is present, are referred to with the umbrella term " Old High German ". In this respect, Old Bavarian is part of Old High German. However, Old High German was very different from region to region, which is why written sources can largely be assigned to the corresponding writing regions. In the course of the tradition, there could be a mix-up because, for example, the scribe and model came from different regions. This explains , for example, the Old Saxon passages in the Old Bavarian Hildebrand song. Numerous primary sources have survived as manuscripts from the old Bavarian language area, which were mainly created in the scriptories of the monasteries Freising , Regensburg , Tegernsee , Benediktbeuern , Passau , Wessobrunn , Mondsee and Salzburg , but were also created by Bavarian-speaking scribes in the Fulda monastery and later in the Benedictine monasteries in Klosterneuburg and Millstatt .

Old Bavarian sources

750-800

- KG Kassel Talks (uncertain: 8th century, Bavaria, old Bavarian)

- MF Mondsee (-Wiener) fragments (end of the 8th century, uncertain: Lorraine, old South Rhine-Franconian or old Bavarian)

- W Wessobrunn creation poem and prayer (766-800, Old Bavarian, maybe also Old Saxon and Old English)

- BR Basler Rezepte (also Fulda recipes , 8th century, Old Upper Franconian, Old Bavarian, ae.)

- LBai Lex Baiwariorum (before 743, Latin, as well as a few old Bavarian or old Franconian)

800-900

- A Abrogans (end of the 8th century, Old Bavarian, copy about 830 Old Alemannic)

- AB Old Bavarian Confession (early 9th century)

- BG Old Bavarian Prayer (also St. Emmeramer Prayer , beginning of the 9th century, uncertain: Regensburg, partly Old Franconian)

- E Exhortatio ad plebem christianam (early 9th century)

- FP Freisinger Paternoster (early 9th century, Bavaria)

- LF Lex Salica Fragment (early 9th century)

- FG Franconian prayer in Bavarian romanization (821, arh.-Franconian and probably Old Bavarian)

- Hi Hildebrandslied (uncertain: original first half of the 8th century, northern Italy; surviving manuscript 9th century, Bavaria or Fulda, Old Bavarian and partly Old Saxon)

- M Muspilli (uncertain: 9th century, 810, 830, Old Bavarian)

- PE Freisinger Priestereid (uncertain: first half of the 9th century, old Bavarian)

- C Carmen ad Deum (mid-9th century)

- P Petruslied (Freising's supplication to St. Peter) (uncertain: middle of the 9th century)

- BB Vorauer confession (end of the 9th century)

900-1100

- Psb Psalm 138 (around 930, Old Bavarian)

- SG Sigihards prayers (uncertain: early 10th century, old Bavarian)

- WS Wiener Hundesegen (uncertain: first half of the 10th century, old Bavarian)

- PNe Pro Nessia (uncertain: 10th century, old Bavarian)

- JB Younger Bavarian Confession (1000)

- Wessobrunn sermons (also known as Old High German sermon collections A – C , 11th century)

- OG Otloh's prayer (after 1067, old Bavarian)

- Oculorum Dolor (11th century, Munich, Old Bavarian)

- R Ruodlieb-Glossen (11th century, Tegernsee Abbey)

- Klosterneuburg prayer (11th century, Middle Bavarian)

- Contra malum malannum (second half of the 11th century; half Old High German, half Latin magic blessing against swam )

- Wiener Notker (late 11th century)

- Millstätter Blutsegen (12th century, South Bavarian)

literature

- Anthony Rowley : The Bavarian superlative. In: Maik Lehmberg (Hrsg.): Language, speaking, proverbs. Steiner, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-515-08459-2 , as seen at: Google Books

- Werner Besch , Anne Betten, Oskar Reichmann, Stefan Sonderegger: Language history: a handbook on the history of the German language and its research. Walter de Gruyter, 2003, ISBN 3-11-015883-3 , pp. 2906ff. Old Bavarian

- Gerhard Köbler: Old High German Dictionary. 4th edition. 1993. Classification of the sources, online under: Old High German Dictionary - University of Innsbruck

- Eva and Willi Mayerthaler: Aspects of Bavarian syntax or Every language has at least two parents. In: Jerold Edmondson et al. a. (Ed.): Development and Diversity. Language variation across time and space. A Festschrift for Charles-James N. Bailey. The Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington, 1990, pp. 371-429.

- Willi Mayerthaler, Günther Fliedl, Christian Winkler: The Alps-Adriatic region as an interface between Germanic, Romance and Slavic: infinitive prominence in European languages. Narr, Tübingen 1995, ISBN 3-8233-5062-5 .

- Ingo Reiffenstein: Aspects of a linguistic history of Bavarian-Austrian up to the beginning of the early modern period. In: Werner Besch (Hrsg.): Sprachgeschichte: A handbook on the history of the German language and its research. 3rd volume, 2nd edition. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, ISBN 3-11-015883-3 , pp. 2899-2942, seen at: Google Books

- Hannes Scheutz: Drent and Herent, dialects in the Salzburg-Bavarian border area. University of Salzburg, 2007, with CD.

- Peter Wiesinger (Ed.): Language and Name in Austria - Festschrift for Walter Steinhauser on his 95th birthday. Braumüller, Vienna 1980, ISBN 3-7003-0244-4 . (Writings on the German language in Austria, 6)

- Rolf Bergmann, Ursula Götz: Old Bavarian = Old Alemannic? For the evaluation of the oldest gloss tradition. In: Peter Ernst, Franz Patocka (Ed.): German language in space and time. Festschrift for Peter Wiesinger on his 60th birthday. Edition Praesens, Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-7069-0087-4 , pp. 445-461.

- Stefan Sonderegger : Old High German Language and Literature, An Introduction to the Oldest German: Representation and Grammar. Walter de Gruyter, 2003, ISBN 3-11-017288-7 . (Chapter 2.6 Temporal structure of the monuments)

Web links

- Isabel Alexandra Knoerrich: Romanisms in Bavarian: an annotated dictionary with maps of the Upper Bavarian Language Atlas (SOB) and the Small Bavarian Language Atlas (KBSA) as well as a discussion on morphosyntax and syntax. Dissertation, University of Passau, 2002

- Josef Bayer, Ellen Brandner: Clitized too in Bavarian and Alemannic. University of Konstanz, pp. 1–21

Individual evidence

- ^ Latin language relics in the Bavarian dialect. A dictionary of Latin: Bavarian

- ↑ Elisabeth Assmann: clitic doubling in Spanish and Catalan. Master's thesis, Institute for Romance Languages and Literatures. Johann Wolfgang Goethe University. Frankfurt am Main, October 12, 2012

- ^ Elisabeth Hamel: The Raetians and the Bavarians. Traces of Latin in Bavarian. In: Bernhard Schäfer (Ed.): Land around the Ebersberger Forest. Contributions to history and culture. 6 (2003), Historical Association for the District of Ebersberg eV, ISBN 3-926163-33-X , pp. 8-14

- ↑ Hans-Hugo Steinhoff: Contra malum malannum. In: Burghart Wachinger et al. (Hrsg.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . 2nd, completely revised edition, ISBN 3-11-007264-5 , Volume 2 ( Comitis, Gerhard - Gerstenberg, Wigand. ) De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1980, Sp. 9 f.