Alemanni

The Alamannen or Alemannen were an antique and early medieval population which the West Germanic culture is assigned.

Alemannic populations are identified using both archaeological sources (such as population customs and costumes) and historical sources (written evidence). Remaining core areas of their early medieval settlement and dominion areas, the Alamannia ( Alemannia ), were mainly in the area of today's Baden-Württemberg and Alsace , in Bavarian Swabia , German-speaking Switzerland , Liechtenstein and Vorarlberg . They shared these areas mostly with Gallo-Roman and Rhaetian population groups.

Between the 6th and 9th centuries, Alemannia was politically and culturally integrated in Eastern Franconia and between the 10th and 13th centuries it was again politically consolidated by the Staufer Duchy of Swabia .

Modern dialectology used the Alemanni to classify the German dialects and called the West Upper German dialects " Alemannic dialects ".

Concept history

Ancient and Middle Ages

Traditionally, the first testimony of the Alemanni by name in an ancient source is associated with a short campaign by Emperor Caracalla in the summer of 213 against Teutons in the Danube region. According to Byzantine excerpts from a lost part of Cassius Dio's historical work , some of the opponents were Alemanni. This identification was generally accepted in the older research that followed Theodor Mommsen , but has been frequently contested since 1984. Cassius Dio, who otherwise does not know the Alemanni in his work, had the designation "Albanians" ( Albannôn ) at the point in question, which referred to a completely different campaign by Caracalla in Asia , and only the Byzantine version, which was only is incomplete, it was replaced by the expression " Alamannôn " ( Alamannôn ) out of ignorance . The hypothesis that the Alemanni name was not in Dio's original text was put forward in 1984 by Matthias Springer and Lawrence Okamura, who came to this conclusion independently of one another. Also independently of them, Helmut Castritius came to the same conclusion in 1986. A number of other researchers have followed this view, including Dieter Geuenich . The authenticity of the position at Cassius Dio still has supporters; Bruno Bleckmann (2002), Ludwig Rübekeil (2003) and Klaus-Peter Johne (2006), among others , have defended them against criticism, whereupon Springer and Castritius have confirmed their arguments. If one excludes the supposed first mention in the year 213, the mention in a panegyric from the year 289 would be the first evidence of the Alamann's name.

The meaning of the name, which appears in its Latin form Alamanni and later also Alemanni in AD 289 , is, according to the prevailing Germanist view, a combination of Germanic * ala- "all" and * manōn- "man, man". However, the original meaning of this composition is disputed. Most likely it is the naming of a "in warlike ventures a new tribe" which "called itself Alemanni (or was called so) because it broke the old tribal connections and was open to everyone who wanted to participate". This interpretation is supported by the interpretation of the Roman historian Asinius Quadratus , who explains the name as "people who have come together and mixed up". The emergence of the Alamanni could therefore be seen as a growing together of followers, family groups and individual people of different origins.

The term " Swabia " (which goes back to the Suebi mentioned in early Roman sources ) developed into a synonym for "Alemanni" or "Alemannien" / "Alamannien" in the early Middle Ages and replaced them in the course of the Middle Ages. There are essentially two theories about the origin of the double name:

- The Alemanni are essentially Elbe Germans , so it is possible that they came to a large extent from tribes that belonged to the Suebi. The name Sueben has been retained as a self-designation and only replaced the external name Alamannen in the early Middle Ages .

- Archaeological influences from the Danube area in Alamannia can be found in the 5th century. It was suspected that these were due to the Donausueben migrated from there , who brought their name to the Alamanni.

A distinction was made between Alemanni and Suebi up to around 500, but from the 6th century the two names are expressly passed down as being synonymous. However, the Suebi name prevailed when the settlement area of the Alamanni, which until then had been called Alamannia , became the Duchy of Swabia .

Modern times

At the beginning of the 19th century, the historical name was first reintroduced in the form of the Germanized adjective allemannisch for the dialects on the Upper and Upper Rhine. So was Johann Peter Hebel 1803 published in the Wiesentaler dialect authored band name Allemannische poems . Linguistics then referred to all Southwest Upper German dialects (including Swabian) as Alemannic, referring to the historical Alemanni . Accordingly, regional house construction methods and local customs were also named as Alemannic , such as the Alemannic carnival . In the tradition of Johann Peter Hebels literature, "Alemannic" is now the popular self-name of the inhabitants of southern Baden for their dialect, whereas Alsatians and Swiss call their dialect Alsatian or Swiss German .

For the northeastern part of the Alemannic dialect area, the dialect and self-designation Swabian has remained common, which is why the local population mostly calls themselves Swabians . The population around the High and Upper Rhine, and even more so in Alsace, Switzerland and Vorarlberg, do not consider themselves to be Swabians, or have long stopped. In Baden-Württemberg , for example, the residents of the former state of Baden often distinguish themselves as Alemanni from the Swabians from Württemberg ; The situation is similar with German-speaking Swiss , in Central Swabia and in the Allgäu , cf. Swabians and Alemanni and ethnic group in the article Swabia .

The use of the terms “Alemanni” and “Alemanni” in specialist antiquity is dependent on the method and source. Historian write Alemanni and medievalists Alemanni .

"Alemannia" as the name for "Germany"

Towards the end of the 13th century, the term regnum Alamanniae instead of regnum Theutonicum for the narrower area of the “German” kingdom was used in the Holy Roman Empire . This reflected the shift in the political focus of the Reich to the German south. Before that time, the term was rarely used. This means that the use of Alamannia as an old or alternative name for the Duchy of Swabia and the previous title of rex Romanorum of the German king is gradually disappearing . This change in the title also had political reasons and coincided with the interregnum or the kingship of Rudolf von Habsburg . In contrast to the country name, the change in the title to rex Alamanniae could not prevail. The mendicant orders that emerged during this time use Alamannia accordingly for their German-speaking provinces. This title is also adopted in England, France and Italy as rei de Alemange , rois d'Allmaigne , rey d'Alamaigne .

In the empire itself, from the 14th century onwards, the designation German land began to gain acceptance and the use of Alamannia was lost for Germany and was only passed on outside the country. That left anglais or Allemagne in French the term for German and Germany. Taken from there are alemanes going on in Spanish , els alemanys in Catalan , os alemães in Portuguese , Almanlar in Turkish , Elman or Alman in Arabic , Kurdish and Persian (see also: German in other languages ).

Alemanni tribes

A uniform tribal leadership of the early Alemanni cannot be proven. Instead, in the Roman sources of the 3rd to 5th centuries, Alemannic tribes are occasionally named, which in turn had their own kings . Well-known Alemanni tribes are the Juthungen , who were settled north of the Danube and Altmühl , the Bucinobanten (Bucinobantes in Latin) in the Main estuary near Mainz , the Brisgavi , who, as the name suggests, were based in the Breisgau , the Rätovarians in the area around the Nördlinger Rieses and the Lentiens , who are suspected to be in the Linzgau area north of Lake Constance.

General story

The Alemannia

Under the Alemannia (or Alamannia , Alemannia, Alamannia) there are various ideas. This can mean:

- Archaeologically tangible settlement areas of Alemanni

- political-military domains of Alemanni (including those of Alemanni dukes and kings)

- Distribution area of Alemannic dialects or languages .

These three territorial concepts are by no means congruent, but have probably largely overlapped in the course of history.

The Alemanni developed in the course of the 3rd century AD, presumably from various Elbe-Germanic , including Suebian tribes , army hordes and followers in the area between the Rhine , Main and Lech .

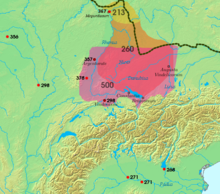

Teutons on the Limes - until around 260 AD

Already since the time of the Suebian king Ariovist in the 1st century BC. In BC, Suebian associations migrated from the Elbe / Saale area to the Rhine / Main / Neckar area. After the end of the Roman Teutonic Wars in the 1st century, small Germanic settlement groups appeared in the Upper Rhine Zone between Mainz and Strasbourg and in the lower Neckarland, for which the name Suebi Nicrenses has been passed down. While these Suebi became Romanized in the course of time in the Roman Empire, new groups of Germanic peoples appeared in front of the Roman Limes at the beginning of the 3rd century , and from 213 on they repeatedly invaded the Roman province on raids. It is not certain whether these groups were already called Alamanni at that time . It is also unclear whether these associations referred to themselves as Alamanni or whether the Romans used this term for the Germanic groups on the Upper and Middle Rhine to distinguish them from other Germanic associations.

The assumption often expressed in the past that the Alemanni formed in the interior of Germania is now considered outdated. There are no reliable findings about this, as only archaeological finds and no written sources are available. The origin of the new settlers can, however, be determined on the basis of the archeological material culture they have brought with them, which can best be compared with the Elbe Germanic region between East Lower Saxony and Bohemia , especially between North Harz , Thuringian Forest and Southwest Mecklenburg .

The end of the Limes

Larger attacks are recorded in 213 and 233/234. According to the later report by Gregory of Tours ( Decem Libri Historiarum , 1, 32–34), the Alemanni invasion of Gaul under King Chrocus in the 50s of the 3rd century is said to have completely devastated the country. Emperor Gallienus succeeded in defeating the Alemanni near Milan in 260, and Roman troops were also able to win a victory over the Juthung near Augsburg (see Augsburg Altar of Victory ), but the Roman Empire, shaken by civil wars and external invasions, was able to break through a time of severe crisis ( Imperial crisis of the 3rd century ), the Limes and thus the area north and east of the Rhine in southern Germany, the Dekumatland , no longer hold. After troops had been withdrawn from the border several times for internal Roman battles, at least the military protection of this province must have been given up around 260.

As a result of the Limesfall, Germanic groups were able to settle in the unprotected area, which was then called Alamannia by the Romans up to the Main . After that, the Roman reports about the Alamanni as a name for the Germanic associations in the above-mentioned area increased. The majority of ancient historical and archaeological research today is of the opinion that the tribe or tribal group of the Alemanni slowly formed from various Germanic settler groups only after the Dekumatland was settled. Recently, the thesis has also been discussed that the penetration of the Germanic tribes took place with the consent of Rome, which gave the newcomers the security of the apron and bound them to itself through foedera . In addition, it should be noted that, strictly speaking, one cannot speak of the Alamanni, as the numerous small groups lacked uniform leadership for a long time.

On April 21, 289 AD, Mamertinus gave an eulogy for Emperor Maximianus in Augusta Treverorum (Trier) and mentioned the Alamanni . This is the first contemporary mention of the Alemanni. From this year, the name Alamannia can also be detected for the area north of the Rhine . A first mention of the Alamannes for the year 213, when, according to the report of the Roman historian Cassius Dio (around 230), Emperor M. Aurelius Antoninus Caracalla assumed the nickname Alamannicus after a victory over the Alamanni , is, as already mentioned, in their Reliability has become very controversial.

Around the year 260 AD the Limes was taken back on a new line, the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , which only covers the eastern and southern parts of the Roman province of Raetia ( e.g. today's Allgäu, Upper Bavaria and Switzerland) protected. This was heavily fortified at the beginning of the 4th century. The new border line to the Alamanni was able to defend the Roman border until 401 AD (withdrawal of the Roman legions) and 430 AD (withdrawal of the Burgundians , who took over the border protection as foederatii ). Burglaries by the Alamanni (more precisely Juthungen ) in the years 356 and 383 could still be warded off, or in the years 430 and 457 they were only repulsed in Italy.

Settlement

The early Alemannic settlements often arose near the ruins of the Roman castles and villas, but not in their buildings. The stone buildings of the Romans were only rarely used for a while (e.g. through wooden fixtures in a bathing building in the villa near Wurmlingen ). Most of the time, the early Alemanni built traditional post buildings with wattle walls plastered with clay. However, there is little evidence of the early Alemanni. Settlement finds like those of Sontheim im Stubental are the exception. Even grave finds such as a woman's grave near Lauffen am Neckar or the children's grave in Gundelsheim are relatively rare. Presumably the area was only slowly populated by infiltrating Germanic groups. Only in certain areas, for example in the Breisgau , can settlement concentrations be determined early on, which may be related to the targeted settlement by the Romans to protect the Rhine border. Alemannic hill castles existed as early as the 4th century, such as on the Glauberg and Runden Berg near Bad Urach .

The population of southwest Germany in Roman times consisted primarily of Romanized Celts, in the northwest also Romanized Teutons (e.g. the Neckarsueben ) and immigrants from other parts of the empire. It is not exactly known to what extent parts of this population remained in the country after the Roman administration withdrew. The continuity of some river, place and field names suggests, however, that provincial Roman parts of the population were absorbed in the Alamanni. In the middle of the Black Forest, for example, a Romance language island may continue to exist until the 9th / 10th Century assumed.

Late antiquity

The historical sources on the early Alemanni are as sparse as the archaeological ones. The accounts of Ammianus Marcellinus illuminate parts of the fourth century somewhat better. It is the most important source, especially for the subdivision into sub-tribes and for conclusions about the political structure.

From the former Dekumatland, the Alemanni repeatedly undertook raids into the neighboring provinces of the Roman Empire Raetia and Maxima Sequanorum , but also far into Gaul. They suffered repeated defeats against Roman armies, for example by Emperor Constantius in 298 at Langres and at Vindonissa ( Windisch ). After the costly battle of Mursa in 351 between the Gallic usurper Magnentius and Emperor Constantius II, the Franks and Alemanni broke through the Rhine border together. The Alemanni occupied the Palatinate , Alsace and northeastern Switzerland. Only the victory of Caesar (lower emperor) Julian in the Battle of Argentoratum ( Strasbourg ) 357 against the united Alamanni under Chnodomar secured the Rhine border again. The Alemannic petty kings had to (again?) Contractually bind themselves to Rome. During the reign of Emperor Valentinian I , Alemannic groups succeeded twice, 365 and 368, in penetrating the territory of the empire and, among other things , plundering Mogontiacum (Mainz). After a retaliatory campaign that earned Valentinian I the nickname Alamannicus in 369 , he had the Rhine border secured by a new series of forts, for example in Altrip , Breisach am Rhein and across from Basel . The border on the Upper Rhine was reinforced with a chain of watchtowers ( burgi ). In 374 the Alamanni concluded a lasting peace with Valentinian I under their part-king Makrian . Nevertheless, his successor, Emperor Gratian , had to lead a campaign against the Alamanni again in 378, which is considered the last advance of Roman troops across the Rhine border. After that, the Alemanni were in a federate relationship with the Roman Empire for a long time .

Battles between Alemanni and Romans:

- 259 - Battle of Mediolanum - defeat of the Alamanni against Emperor Gallienus, the train on Rome is broken off .

- 260 - Battle of Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg) - Defeat of the Alamanni against Raetian governors

- 268 - Battle of Lacus Benacus (Lake Garda) - Defeat of the Alamanni against Emperor Claudius II.

- 271 - Battle of Placentia - Victory of the Alemanni against Emperor Aurelianus

- 271 - Battle of Fano - Defeat of the Alamanni against Emperor Aurelianus

- 271 - Battle of Pavia - Defeat of the Juthungen against Emperor Aurelianus

- 298 - Battle of Lingones - Defeat of the Alamanni against Caesar Constantius Chlorus

- 298 - Battle of Vindonissa - Defeat of the Alamanni against Constantius

- 356 - Battle of Reims - Victory of the Alemanni against Caesar Julianus

- 357 - Battle of Strasbourg - Defeat of the Alemanni against Julianus in Alsace

- 367 - Battle of Solicinium - Defeat of the Alemanni against Emperor Valentinian I.

- 378 - Battle of Argentovaria - Defeat of the Alamanni against Emperor Gratian

The usurpation by Magnus Maximus in Britain and the war with the Franks allowed the Alamanni to break into Raetia in 383 , which Emperor Valentinian II could only secure with the support of the Alans and the Huns . Further internal Roman power struggles under Emperor Theodosius I weakened the Roman position on the Rhine. The army master Stilicho succeeded in 396/398 in renewing the contracts with the Alamanni, but from 401 he had to withdraw the Roman troops from the imperial border to protect Italy from the Goths . According to the latest findings, however, there does not appear to have been an immediate "Alemannic storm" in the formerly Roman areas. Archaeological finds indicate that the federated Alemanni protected the border for at least quite a while. Rhaetia in particular was defended as the “protective shield of Italy” until the middle of the 5th century: Roman troops fought off Alemannic incursions into Raetia and Italy in 430 under Flavius Aëtius and 457 under Emperor Majorian . Gaul was more or less defenseless at the mercy of the Alemanni raids and, according to the (late) chronicler Fredegar, was repeatedly devastated after 406.

Expansion and submission

From 455 a west and east expansion from Alamannen to Gaul and Noricum began, about which only unsecured information is available. The mentioned expansions can hardly be traced archeologically . In terms of material culture and burial customs, within the row burial culture, for example, to the Franks, only flowing transitions can be made out, but hardly any clear cultural boundaries. There are even fewer differences to the Germanic tribes to the east, the later Bavarians . Statements about this are essentially derived from written sources. Settlement by Alamannic population groups or even only temporarily Alamannic supremacy extend north to the area around Mainz and Würzburg , south to the foothills of the Alps , east to the Lech or along the Danube almost to Regensburg , west to the eastern edge of the Vosges , beyond the Burgundian Gate to Dijon and southwest in the Swiss Plateau to the Aare .

According to Gregory of Tours, a conflict with the neighboring Franks led to decisive defeats of the Alamanni against the Franconian King Clovis I of the Merovingian dynasty sometime between 496 and 507 . He is said to have adopted the Christian (Catholic) faith in connection with the victory after a decisive battle. The decisive battles were possibly the Battle of Zülpich and the Battle of Strasbourg (506) . The northern Alemannic areas came under Frankish rule. The Ostrogoth king Theodoric initially put a stop to the Frankish expansion by placing the southern parts of Alamannia under Ostrogothic protectorate and taking refugees from the defeated Alemanni under his protection. But already in 536/537 the Ostrogoth king Witigis, besieged by the Byzantine troops, left the Frankish king Theudebert I, among other things, Churrätien and the protectorate of "the Alamanni and other neighboring tribes" in order to buy the support of the Merovingians. This meant that all the Alemanni were under Frankish rule.

With the subjugation of the Alamanns by the Franks, their sovereignty ended, and dukes were irregularly installed by the Franconian kings for the Alamannic area. However, due to the sources, it is not possible to create a complete linear list. It is believed that Franconian nobles were settled in strategically important places in order to secure control of the country. This is confirmed in grave finds with foreign forms of jewelry and weapons that come from the West Franconian region or the Rhineland. Members of other peoples of the Franconian Empire were also settled in the Alemannic area, which is reflected in place names such as Türkheim (Thuringian), Sachsenheim or Frankenthal to this day. Only after incorporation into the Franconian Empire was further settlement or Germanization of the Romanesque areas adjoining to the south possible. According to the findings of more recent archaeological research, Alemannic settlement activity in today's German-speaking Switzerland did not begin before the end of the 6th century.

Alamannia among Merovingians and Carolingians

Alamannia was consolidated through its autonomous status in the Franconian Empire as a duchy in an area that probably largely coincides with the later Duchy of Swabia. However, Alsace was mostly run as a separate duchy and actually did not belong to Alemannia. The focus of the Franconian Duchy of Alamannien was in the area south of the High Rhine and in the Lake Constance area. The dukes still came from various noble Alemannic families and were not always in competition with Franconian nobles. For example, founded a Alamannic Duke along with the Frankish house Meier , the Monastery of Reichenau . The relatively autonomous dukes of the Franconian Empire often tried to break away from their dependence on the Frankish king. So he had to repeatedly take action against rebellious Alemannic dukes. In 746, the so-called blood court at Cannstatt , the resistance was finally broken: The Duchy of Alamannia was abolished and ruled directly by the Franks. With this the Alemannic duke title disappeared for a long time. However, Emperor Ludwig the Pious tried to create a kingdom of Alemannia for his son Charles II between 829 and 838 .

In the 7th century, parts of the upper class began to bury their dead no longer in the row grave fields, but at the manor house. During this time, stone boxes often mark the graves. Due to Christianization at the beginning of the 8th century, the row grave fields were completely abandoned and the cemeteries were created around the church in future. This also means that the most important source for the archeology of the Alemanni is no longer available.

In the 10th century the East Franconian / German duchy of Alamannien was founded. This duchy can be narrowed down to some extent, and its Franconian district division is more or less secured. After the investiture controversy, the duchy was effectively divided in 1079. The Thurgau, the Black Forest, the Breisgau and the Ortenau, which also belonged to the Duchy, always remained under Zähringian rule. Until then, the duchy was still called the Duchy of Alamannien, but this name has now disappeared and was henceforth called the Duchy of Swabia.

Disputed areas were still Alsace and Aargau , which were claimed by the neighboring Duchy of Lorraine and the Kingdom of Burgundy . The name Alemannia fell out of use and over time was only used as a scholarly historicizing term.

religion

The Alemanni revered the old Germanic deities until the 7th century, witnessed are Wodan , to whom beer offerings were made, and Donar . The gold Brakteat from Daxlanden also shows a man in a bird's metamorphosis probably Odin and two other bracteates show a goddess, that the mother of the gods Frija can be identified. On the other hand, the veneration of the Zîu can only be proven on the basis of philological evidence. Beings of lower mythology show Gutenstein's sword with the image of a werewolf or Pliezhausen's rider's disk. The Vita of St. Gallus names two naked water women who threw stones at the saint's companion. When he banished them, they fled to the Himilinberc , where demons lived, which is reminiscent of the Nordic seat of gods Himinbjörg .

The Roman writer Agathias tells of the Alemanni who invaded Italy in 553 that they worshiped certain trees, the waves of the rivers, hills and gorges and sacrificed horses, cattle and other animals to them by cutting off their heads. He also calls Alemannic seers. Archeology uncovered several victim finds. In the 4th century, for example, gun points were deposited in the Rautwiesen spring moor near Münchhöf (Gm. Eigeltingen , Hegau) and the aforementioned gold bracteate from Daxlanden was buried together with a horse's skull and an iron ax.

The burial is also evidence of the ancient religion. So the Prince of Schretzheim was buried together with his horse, groom and cupbearer. Gold leaf crosses and other Christian objects show that the Alemanni came into contact with Christianity early on, but there is several written and archaeological evidence of syncretism . In the middle of the 5th century, a new form of burial prevailed among the Alemanni - as with other neighboring West Germans. Up to now, in the Elbe Germanic tradition, cremations in small grave groups or even isolated graves were common. Such graves are difficult to record archaeologically and, due to the burning, are also difficult to evaluate. Even in the early days there was also an increasing number of body burials. With the change to row burial practice, such as B. in the cemetery of Stuttgart-Feuerbach , the source situation changes dramatically for archeology. Large cemeteries are now being laid out, in which the dead are buried unburned in an east-west direction in rows close together. From this time (until around 800 the row grave fields are again given up in favor of burials around the church), more detailed statements about material culture, handicrafts, population structure, diseases, combat injuries and social structure are possible.

After the conquest by the Franks, the Alemanni began to proselytize, particularly through the Irish missionaries Fridolin , Columban and his followers. After Säckingen they founded the monasteries of St. Gallen (614), St. Trudpert and Reichenau (724). In Alamannia there were bishops in Basel (formerly in Augusta Raurica near Basel), Constance , Strasbourg and Augsburg from Roman times . Church relationships were first established in the 7th century in the Lex Alamannorum , an early codification of Alamannic law. There was probably an uninterrupted existence of Christians in the ancient Roman areas south and west of the Rhine, at least in the cities and in the Alpine valleys. Only the bishopric in Vindonissa (Windisch) had perished in Alamannia since Roman times .

Museums

- Alemanni Museum Vörstetten

- Alamannenmuseum Ellwangen

- Alemanni Museum Weingarten (Ravensburg district)

- Archaeological Museum in the Colombischlössle in Freiburg im Breisgau

- Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg in Constance

- State Museum Württemberg in Stuttgart

- Swiss National Museum in Zurich

- City and Hochstift Museum in Dillingen on the Danube

- Museum Auberlehaus in Trossingen

swell

- Gregory of Tours : Ten Books of Stories . Volume 1, Book 1-5. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1991, ISBN 3-534-06809-2 .

- Bruno Krusch (ed.): Fredegarii et aliorum Chronica. Vitae sanctorum . (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores rerum Merovingicarum . Volume 2). Hahn, Hanover 1888.

See also

- Alemannic discourse in the 20th century

literature

- General

- Bruno Bleckmann : The Alemanni in the 3rd century: Ancient historical remarks on the first mention and on ethnogenesis. In: Museum Helveticum . Volume 59, 2002, pp. 145-171.

- Michael Borgolte : The Counts of Alemannia in Merovingian and Carolingian times. A prosopography. Jan Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1986, ISBN 3-7995-7351-8 .

- Rainer Christlein : The Alemanni. Archeology of a Living People. Theiss, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-8062-0890-5 .

- John F. Drinkwater: The Alamanni and Rome 213-496. Caracalla to Clovis. Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-929568-5 .

- Dieter Geuenich (ed.): The Franks and the Alemanni up to the "Battle of Zülpich" (496/497). In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Supplementary volume 19, Berlin / New York 1998, ISBN 3-11-015826-4 .

- Dieter Geuenich: History of the Alemanni. 2nd, revised edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-17-018227-7 .

- Andreas Gut (Hrsg.): The Alamannen on the Ostalb: Early settlers in the area between Lauchheim and Niederstotzingen. (= Archaeological information from Baden-Württemberg. Issue 60). Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-942227-00-1 .

- Maximilian Ihm : Alamanni . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 1, Stuttgart 1893, Sp. 1277-1280.

- Hans Jänichen , Hans Kuhn , Heiko Steuer : Alemannen. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 1, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1973, ISBN 3-11-004489-7 , pp. 137-163.

- Reinhold Kaiser: Alemanni (Alemanni). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Klaus Georg Kokkotidis: From the cradle to the grave - Investigations into the paleodemography of the Alemanni of the early Middle Ages. (PDF; 2.1 MB). Dissertation. Cologne, 1999.

- Karin Krapp: The Alamanni: Warriors - Settlers - Early Christians. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2044-5 .

- Wolfgang Müller: On the history of the Alemanni. Ways of research. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1975, ISBN 3-534-03457-0 .

- Lawrence Okamura: Alamannia devicta. Roman-German Conflicts from Caracalla to the First Tetrarchy (A.D. 213-305). Dissertation. Ann Arbor 1984.

- Ludwig Rübekeil : Suebica - people names and ethnos. (= Innsbruck contributions to linguistics. 68). Institute for Linguistics, Innsbruck 1992, ISBN 3-85124-623-3 .

- Alexander Sitzmann, Friedrich E. Grünzweig: The old Germanic ethnonyms. In: Hermann Reichert et al. (Ed.): Philologica Germanica. Volume 29, Fassbaender, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-902575-07-4 .

- Heiko Steuer : Germanic army camps of the 4th / 5th centuries Century in southwest Germany. (PDF; 2.0 MB). In: Anne Nørgård Jørgensen (Ed.): Military aspects of Scandinavian society in a European Perspective. AD 1-1300: papers from an International Research Seminar at the Danish National Museum. Copenhagen 1997, ISBN 87-89384-54-7 , pp. 113-122.

- Claudia Theune : Teutons and Romans in the Alamannia. Structural changes due to the archaeological sources from the 3rd to the 7th century. de Gruyter, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-11-017866-4 .

- Reinhard Wenskus : Tribal formation and constitution. The emergence of the early medieval gentes. 2nd, unchanged edition. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne / Vienna 1977, ISBN 3-412-00177-5 .

- Thomas Zotz : Ethnogenesis and Duchy in Alemannia (9th – 11th centuries) . In: Communications from the Institute for Austrian Historical Research. Volume 108, 2000, pp. 48-66, ISSN 0073-8484 .

- Thomas Zotz, Hermann Ament: Alemanni, Alemanni . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 1, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7608-8901-8 , Sp. 263-266.

- Museums, exhibition catalogs

- The Alemanni . Edited by the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8062-1302-X .

- Karlheinz Fuchs, Martin Kempa, Rainer Redies: The Alamanni. Exhibition catalog . Theiss, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1535-9 .

- Michaela Geiberger (Ed.): Imperium Romanum. Romans, Christians, Alamanni - The Late Antiquity on the Upper Rhine Book accompanying the exhibition . Theiss, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1954-0 .

- Andreas Gut : Alemanni Museum Ellwangen . Fink, Lindenberg 2006, ISBN 3-89870-271-5 .

Web links

- Project of the University of Duisburg on the history of the Alemanni ( Memento from May 13, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Alamanni and Sueben: from the history of the southwest German language area ( Memento from January 25, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (including: "witnesses" for the use of "Alemannic" and "Swabian"; maps of the expansion of the Alemanni in the 3rd to 5th century AD)

- Alamanni between the Black Forest, Neckar and Danube ; Special exhibition of the Reutlinger Heimatmuseum from March 29th to May 24th, 2009

- Heiko Steuer: Theories on the Origin and Origin of the Alemanni - Archaeological Research Approaches (PDF; 2.0 MB), original article published in: Dieter Geuenich (Hrsg.): The Franks and the Alemanni up to the "Battle of Zülpich" (496/97) . Berlin / New York 1998, pp. 270-324.

Remarks

- ↑ For the chronology and the course of the campaign see Andreas Hensen: Zu Caracallas Germanica Expeditio. Archaeological-topographical investigations. In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg. Volume 19, No. 1, 1994, pp. 219-254.

- ↑ The original definition comes from Theodor Mommsen , after this campaign “was waged against the Chatti ; but next to them a second people is mentioned that is meeting here for the first time, that of the Alemanni. "The" unusual skill of the Alemanni in cavalry "was mentioned. Mommsen saw the origin in "crowds advancing from the east", in connection with the displaced, "mighty Semnones who lived on the middle Elbe in earlier times ". quoted from the unabridged text edition Theodor Mommsen: The Roman Empire of the Caesars. Safari-Verlag, Berlin 1941, p. 116 f.

- ↑ Helmut Castritius, Matthias Springer: Was the name of the Alemanni mentioned in 213? Berlin 2008, p. 434f.

- ↑ Lawrence Okamura: Alamannia devicta. Roman-German Conflicts from Caracalla to the First Tetrarchy (A.D. 213-305). Ann Arbor 1984, pp. 8-10, 84-133; Matthias Springer: The entry of the Alemanni into world history. In: Treatises and reports of the Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden, research center. Volume 41, 1984, pp. 99-137. Camilla Dirlmeier, Gunther Gottlieb (ed.): Sources on the history of the Alamanni from Cassius Dio to Ammianus Marcellinus offer a compilation of the sources with translation . Sigmaringen 1976, pp. 9-12. See Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer. Ann Arbor 1994, pp. 141 f.

- ↑ Helmut Castritius, Matthias Springer: Was the name of the Alemanni mentioned in 213? Berlin 2008, p. 432.

- ^ Dieter Geuenich: History of the Alemanni. 2nd, revised edition. Stuttgart 2005, p. 18 f. and Helmut Castritius : From political diversity to unity. On the ethnogenesis of the Alemanni. In: Herwig Wolfram , Walter Pohl : Types of ethnogenesis with special consideration of Bavaria. Part 1, Vienna 1990, pp. 71–84, here: 73–75.

- ↑ Bruno Bleckmann: The Alamanni in the 3rd century: Ancient historical remarks on the first mention and on ethnogenesis. In: Museum Helveticum . Vol. 59, 2002, pp. 145–171, here: 147–153, 170. John F. Drinkwater also follows his view: The Alamanni and Rome 213–496 (Caracalla to Clovis). Oxford 2007, p. 43 f. and Markus Handy: The Severers and the Army. Berlin 2009, pp. 82–87.

- ↑ Helmut Castritius, Matthias Springer: Was the name of the Alemanni mentioned in 213? Berlin 2008, p. 432 u. Note 7.

- ↑ Helmut Castritius, Matthias Springer: Was the name of the Alemanni mentioned in 213? In: Uwe Ludwig, Thomas Schilp (Ed.): Nomen et Fraternitas. Festschrift for Dieter Geuenich (= supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , vol. 62). De Gruyter, Berlin 2008, pp. 431-449.

- ↑ Helmut Castritius, Matthias Springer: Was the name of the Alemanni mentioned in 213? Berlin 2008, p. 433.

- ↑ Hans Kuhn : Alemanni. § 1: Linguistic. In: Heinrich Beck u. a. (Ed.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . 1. Volume: Aachen - Bajuwaren. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1973, ISBN 3-11-00489-7 , p. 137 f .; the reconstructed approaches according to the Etymological Dictionary of the German Language . 25th, revised and expanded edition. edit by Elmar Seebold , de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, s. vv.

- ^ A b Hans Kuhn : Alemanni. § 1: Linguistic. In: Heinrich Beck u. a. (Ed.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . 1. Volume: Aachen - Bajuwaren. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1973, ISBN 3-11-00489-7 , p. 137 f., Here p. 138.

- ↑ Asinius Quadratus 'declaration from the late antique author Agathias handed (580), see Agathias 1.6: Οί δέ' Αλαμανοί, εϊ γε χρή Άσινίω Κουαδράτω επεσθαι, άνδρί Ίταλιώτη και τά Γερμανικά ές τό ακριβές άναγεγραμμένφ , σύγκλυδές είσιν άνθρωποι καί μιγάδες · και τούτο δύναται αύτοίς ή έπωνυμία. “But the Alemanni, if one may believe Asinius Quadratus, a man from Italy who described the German Wars in detail, are people who have come together and mixed; and that also means her name. "

- ↑ D. Geuenich: History of the Alemanni. 1997, p. 13 f.

- ↑ D. Geuenich: On the continuity and the limits of Alemannic in the early Middle Ages. In: P. Fried, W.-D. Sick (ed.): The historical landscape between Lech and Vosges. (= Publications of the Alemannic Institute Freiburg. 59). Weißenhorn 1988, pp. 115-118.

- ^ Rudolf Post , Friedel Scheer-Nahor: Alemannic dictionary for Baden (= series of publications of the regional association Badische Heimat. Volume 2). Edited by the regional association Badische Heimat and the Muettersproch-Gsellschaft. Braun, Karlsruhe 2009.

- ↑ D. Mertens: Late medieval country consciousness in the area of old Swabia. In: M. Werner (Hrsg.): Late medieval country consciousness in Germany. (= Lectures and research. 61). Ostfildern 2005, pp. 98-101.

- ↑ Alexander Demandt : The West Germanic tribal formation. In: Klio . Volume 75, 1993, pp. 387-406, note 1.

- ↑ Ernst Schubert: King and Empire. Studies on the late medieval German constitutional history (= publications of the Max Planck Institute for History. 63). Göttingen 1979, pp. 227-231.

- ↑ Ernst Schubert: King and Empire. Studies on the late medieval German constitutional history. (= Publications of the Max Planck Institute for History. 63). Göttingen 1979, p. 238 f.

- ↑ So-called Black Forest Romance : K. Kunze: Aspects of a language history of the Upper Rhine region up to the 16th century. In: W. Besch (Hrsg.): Sprachgeschichte. 2nd Edition. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003, p. 2811 (books.google.de)

- ↑ Renata Windler: Settlement and population of Northern Switzerland in the 6th and 7th centuries. In: Karlheinz Fuchs (Ed.): The Alamannen. Theiss, Stuttgart 1997, pp. 261-268.

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi : Chronicon Helveticum .

- ^ Runic inscription from Nordendorf; Vita Columbani, c. 1.27

- ↑ Karl Hauck: The necklace find from Gudme in Funen…. In: The Franks and the Alamanni up to the Battle of Zülpich. (= Supplement to RGA. 19). Berlin 1998.

- ↑ So the weekday name Zyschtig for Tuesday.

- ↑ M. Axboe, U. Clavadetscher, K. Düwel, K. Hauck, L. v. Padberg: The gold bracteates of the migration period . Iconographic catalog. Munich 1985–1989.

- ^ Walter Brandmüller: Handbook of Bavarian Church History: From the Beginnings to the Threshold of Modern Times. Part I: Church, State and Society. ; Part II: Church Life. EOS Verlag, 1999.

- ^ Hans-Georg Wehling, Reinhold Weber: History of Baden-Württemberg. 2007.