Caracalla

Caracalla (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus ; * April 4, 188 in Lugdunum, today's Lyon ; † April 8, 217 in Mesopotamia ) was Roman Emperor from 211 until his death . His official emperor name was - in connection with the popular emperor Mark Aurel - Marcus Aurel (l) ius Severus Antoninus .

Caracalla's father, Septimius Severus , the founder of the Severan dynasty, made him co-ruler in 197. After the death of his father on February 4, 211, he succeeded him together with his younger brother Geta . In December 211 he had Geta murdered. He then ordered a nationwide massacre of Geta's supporters. From then on he ruled unchallenged as the sole ruler.

Caracalla was mainly concerned with military matters and favored the soldiers. With this he continued a course already taken by his father, which pointed to the era of the soldier emperors. Because of the brutality of his actions against any actual or supposed opposition, he was judged very negatively by contemporary senatorial historiography . With the soldiers, however, he enjoyed great popularity, which continued after his death.

While preparing for a campaign against the Parthians , Caracalla was murdered by a small group of conspirators for personal reasons. Since he was childless, the male descendants of the dynasty founder Septimius Severus died out with him. Later, however, the emperors Elagabal and Severus Alexander were passed off as the illegitimate sons of Caracalla.

The measures with which Caracalla was first and foremost remembered by posterity were the construction of the Caracalla Baths and the Constitutio Antoniniana , a decree of 212 by which he granted Roman citizenship to almost all free imperial residents . Modern research largely follows the unfavorable assessment of his reign by the ancient sources, but counts on exaggerations in the statements of the historians who are hostile to him.

Life until the assumption of power

childhood

Caracalla was born on April 4, 188 in what is now Lyon , the administrative center of the province of Gallia Lugdunensis . He was the elder of the two sons of the future emperor Septimius Severus, an African who was governor of this province at the time. His brother Geta was born just eleven months later . His mother Julia Domna , the second wife of Septimius Severus, came from a very distinguished family; her hometown was Emesa ( Homs ) in Syria. Caracalla was named Bassianus after his maternal grandfather, a priest of the sun god Elagabal, who was worshiped in Emesa .

Caracalla spent a significant part of his childhood in Rome. From 191 his father was governor of the province of Upper Pannonia . The children of the provincial governors had to stay in Rome by order of the emperor Commodus , because the suspicious emperor wanted to protect himself against the risk of uprisings by the governor by keeping their children in his immediate sphere of influence. As a child, Caracalla is said to have had pleasant qualities. He was five years old when his father was proclaimed emperor by the Danube regions on April 9, 193. From the middle of 193 to 196 he stayed with his father in the east of the empire, then he returned to Rome via Pannonia .

From the spring of 195, Septimius Severus posed as the adopted son of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who died in 180, in order to legitimize his rule. With this fiction he wanted to place himself in the tradition of the adoptive emperors , whose epoch was considered to be the golden age of Roman history. Therefore, as the fictional grandson of Mark Aurel, Caracalla was given the name of this popular ruler from 195/196: from then on he was called Marcus Aurel (l) ius Antoninus , and like his father was considered a member of Mark Aurel's family, the imperial family of the Antonines. He always clung to this fiction. Geta, on the other hand, was not renamed, i.e. not fictitiously included in the Antonine family. Even then, this showed a preference for his one year older brother. Caracalla was given the title Caesar either in mid-195 or in 196 at the latest, designating him future emperor. This move marked the break between Septimius Severus and his rival Clodius Albinus , who had Britain under his control. Albinus had hoped for the imperial dignity in 193, but Severus had accepted the title of Caesar and the prospect of a successor. This regulation became obsolete with Caracalla's elevation to Caesar . Therefore the civil war between Severus and Albinus, which had been avoided in 193, broke out. After Severus' victory in this war, in which Albinus was killed, nothing stood in the way of Caracalla's claim to succeed his father.

As the emperor's son, Caracalla received a careful upbringing. So he was not illiterate; as emperor he was apparently able to participate in intellectual conversations and valued rhetorical skills.

In 197 Caracalla and his brother Geta accompanied their father on his second campaign against the Parthians . As early as the spring of 197 he was officially designated as emperor-designate and partner in the rule. In the autumn of 197 or at the latest in 198 he was elevated to Augustus and given imperial powers; henceforth he was called Marcus Aurelius (l) ius Severus Antoninus Augustus . At the same time Geta was raised to Caesar . The imperial family stayed in the Orient for some time; In 199 she traveled to Egypt, where she stayed until 200. She did not return to Rome until 202. That year Caracalla was full consul with his father .

Marriage and conflicts of youth

In April 202, at the age of 14, Caracalla was married by his father against his will to Publia Fulvia Plautilla , who received the title Augusta . She was the daughter of the Praetorian prefect Gaius Fulvius Plautianus . Plautianus came from Leptis Magna in Libya, the hometown of Septimius Severus. Thanks to the favor of the emperor, he had achieved an extraordinary position of power, which he wanted to secure by marriage to the imperial family. His abundance of power was perceived by the Empress Julia Domna as a threat and brought him into conflict with her. Caracalla, who saw Plautianus as a rival, hated his wife and father-in-law and wanted to get rid of both. With an intrigue he brought about the overthrow of Plautianus, with the help of his tutor, the freed Euodus . Euodus had three centurions accuse Plautianus of plotting to murder Severus and Caracalla; they claimed the prefect had instigated an assassination attempt. Severus believed them and summoned Plautianus, but the accused was not given an opportunity to justify, as Caracalla did not let him speak. According to the account of the contemporary historian Cassius Dio , Caracalla tried to kill his enemy with his own hands in the presence of the emperor, but was prevented from doing so by Severus. Thereupon he had Plautianus killed by one of his companions, apparently with the approval of the emperor. Plautilla was exiled to the island of Lipari . After taking office, Caracalla ordered their removal; the damnatio memoriae was imposed on them. Euodus, too, was later executed on Caracalla's orders.

Already in early youth there was a pronounced rivalry between the two brothers Caracalla and Geta, which steadily intensified in the further course of their lives and turned into deadly hatred. Septimius Severus tried in vain to moderate the enmity between his sons and to cover it up from the public, for example by minting coins of Concordia (unity), two joint consulates of Caracallas and Getas in 205 and 208 and keeping the sons away from Rome. Both sons took part in the Emperor's campaign in Britain, which he undertook in 208-211 against the Caledonians and Mates living in today's Scotland . In 209 Geta received the dignity of Augustus , so it was ranked on a par with his previously preferred brother. Since the fighting dragged on and Septimius Severus was already in poor health, he entrusted Caracalla with the sole direction of military operations; Geta received no command. From 210 on Caracalla had the winning name Britannicus maximus , which his father and brother also adopted. He is said to have tried to hasten the death of the emperor by putting his doctors and servants under pressure to harm the sick man. Septimius Severus died on February 4, 211 in Eboracum .

Reign

Assumption of power and power struggle with Geta

As Septimius Severus had intended, his two sons initially came to power together. They made peace with the Caledonians and Mäaten and thus renounced the perhaps originally planned occupation of areas in present-day Scotland. Thus Hadrian's Wall again became the northern border of Roman territory in Britain. The peace seems to have remained stable; apparently the free tribes of the north refrained from invading the realm in the following decades.

Caracalla and Geta returned to Rome with a separate court. There both of them protected themselves from one another by careful guarding. The common rule of Marcus Aurelius and his adoptive brother Lucius Verus in the period 161–169 could serve as a model for a dual empire , but there were significant differences to the situation at that time: Caracalla and Geta had both achieved the rank of Augustus and their hierarchy under their father and powers were unclear. There was no recognized succession regulation, especially no primogeniture. A juxtaposition of two largely equal rulers could theoretically only have been implemented by dividing the empire. The historian Herodian claims that dividing the Roman Empire and assigning Geta to the east was actually considered, but this plan was rejected because Julia Domna, mother of the two emperors, strongly opposed the plan. In recent studies, however, this report is often judged to be implausible. Attempts to find confirmation of Herodian's account in epigraphic material have failed.

A circle of supporters had formed around both brothers; Geta was popular with at least some of the soldiers. Therefore, Caracalla did not dare to take action against him for the time being. The Roman city population, the court, the Senate, the Praetorians and the troops stationed in the capital and its surroundings were divided or indecisive, so that a great civil war seemed imminent.

Finally, in December 211, Caracalla managed to lure his brother into an ambush. He got his mother to arrange a meeting at the imperial palace. Geta recklessly accepted the mother's invitation, because he thought he would be safe from his brother in her presence. The sequence of the fatal encounter is unclear. According to the account of the contemporary historian Cassius Dio , which is considered the most credible, Caracalla ordered murderers who killed his brother in the arms of his mother, injuring her hand. Apparently he also struck himself, because later he consecrated the sword he used in the Serapeion of Alexandria to the deity Serapis, who was worshiped there . Then the damnatio memoriae was imposed on Geta and the eradication of his name in all public monuments and documents was carried out with the greatest thoroughness; even its coins were melted down.

The now sole ruler justified the murder by claiming that he himself had only forestalled an attack by Geta. The day after the crime, he gave a speech in the Senate in which he presented his point of view and at the same time tried to win sympathy for exiles by announcing an amnesty. For the public and especially for the senators, however, the murder was an outrageous breach of taboo, from which Caracalla's reputation was never to recover. He won over the Praetorians with an increase in pay and gifts of money, and the soldiers' incomes were also increased considerably to ensure their loyalty. According to the presentation of the Historia Augusta , the credibility of which is controversial, Caracalla could only appease the Legio II Parthica stationed near Rome , which had strongly sympathized with Geta, with a generous gift of money.

Domestic politics

Reign of terror

Immediately after Geta's murder, Caracalla had numerous men and women who were believed to be supporters of his brother killed; at that time around 20,000 people are said to have been murdered for this reason. According to a controversial thesis, the decapitated victims of a related mass execution may have been discovered in York in 2004. Even later, many were killed who Caracalla accused of harboring sympathy for the defeated rival or of mourning him. Prominent victims of the terror included the emperor's son Pertinax Caesar and two descendants of the widely revered emperor Marcus Aurelius: his daughter Cornificia and a grandson. The famous lawyer Papinian , who was a friend and confidante of Septimius Severus and who had sought a compromise between the warring brothers on behalf of the late emperor, was murdered on the orders of Caracallas after Praetorians had brought charges against him. Senators were among the victims, but the ruler seems to have striven for a tolerable relationship with the Senate; the repression was directed primarily against people of low rank. It became common to use fabricated claims to get rid of personal opponents in anonymous ads. The numerous soldiers and Praetorians in Rome served Caracalla as spies and informants.

An illuminating episode was Caracalla's attempt in the spring of 212 to kill the popular senator and former city prefect Lucius Fabius Cilo . The reason for this was probably that Cilo had tried to mediate between Caracalla and Geta. Caracalla ordered soldiers - apparently Praetorians - to take action against the senator. They ransacked the house of Cilos and led him to the imperial palace with abuse. Then there was a riot; the population and soldiers stationed in the city (urbaniciani) , who had previously been under Cilo's command, intervened on behalf of the arrested person to free him. Caracalla thought the situation was so dangerous that he rushed out of the palace and pretended to want to protect Cilo. He had the Praetorians in charge of the arrest and their commander executed, allegedly as a punishment for their actions against Cilo, but in reality because they had failed to carry out the order. The process shows an at least temporary weakness of the emperor. He had to shrink from resistance from sections of the city population and the city soldiers, on whose loyalty he depended.

In general, Caracalla proceeded with great severity against individuals and groups who aroused his anger or suspicion. A characteristic of his terror was that he not only had suspects executed in a targeted manner, but also took collective punitive measures, which in addition to opposition members also killed numerous harmless people and bystanders. The Alexandria massacre in Egypt caused a sensation . There Caracalla caused a great bloodbath among the population during his stay in the city, which lasted from December 215 to March / April 216. Cassius Dio gives the occasion that the Alexandrians made fun of the emperor. The townspeople were known to be ridiculous, but their insubordination also had a serious background: in the town - presumably for economic reasons - an anti-imperial atmosphere had arisen, which erupted in a riot. The slaughter in Alexandria, which is said to have lasted for days, also fell victim to foreign visitors who happened to be in the city. The city was also sacked by Caracalla's soldiers. Cassius Dio and the historian Herodian, who is also contemporary, probably exaggerate the extent of the massacre, but the description of Cassius Dios is largely correct. When the emperor believed in a chariot race in Rome that an unruly crowd was trying to insult him by mocking one of his favorite charioteers, he ordered his soldiers to kill the troublemakers, which ended in an indiscriminate massacre.

Thermal baths and expansion of Roman civil rights

To this day, Caracalla's name is primarily associated with two spectacular measures: the construction of the Caracalla Baths in Rome, a total of 337 by 328 meters, and the Constitutio Antoniniana of 212. With the construction of the baths, the emperor wanted to attract the city's population make popular. At that time it was the largest such facility in Rome. The Constitutio Antoniniana was a decree that granted Roman citizenship to all free residents of the empire, with the exception of the dediticii . The delimitation of the group of people meant by dediticii is unclear. This expression was originally used to describe members of peoples or states who had unconditionally submitted to the Romans, either in war in the sense of a surrender or in peace in order to receive Roman protection. In legal terms, the Constitutio Antoniniana did not mean, as was previously believed, the abolition of local legal customs and their replacement by private Roman law ; Local law continued to be applied insofar as it did not contradict Roman law. This resulted in legal uncertainties in everyday legal life; a comprehensive, generally applicable regulation was evidently not sought.

The purposes and scope of the Constitutio Antoniniana have not yet been satisfactorily clarified. Caracalla does not seem to have taken any accompanying measures to integrate the new citizens; a comprehensive, long-term overall concept was apparently not associated with the granting of citizenship. Caracalla states that he took the step because he wanted to thank the gods for rescuing him from danger. Presumably he was referring to an alleged murder attempt by Geta, but other interpretations are possible. Cassius Dio gives the opinion of the opposition senatorial circles, according to which the extension of the civil rights had the main purpose to increase the tax revenues; those affected by the decree were made subject to taxes payable only by Roman citizens. Such taxes were a levy on the release of slaves and the inheritance tax, which Caracalla then doubled from 5 to 10 percent. The increase in tax revenue was only one of Caracalla's motives. In addition, he probably wanted to win the new citizens as personally devoted supporters in order to compensate in this way the hostility of the traditional elite, among whom he was hated because of his reign of terror, and thus to strengthen his power base. Numerous new citizens adopted the name of the emperor (Aurelius), who became extremely common as a result.

Administration, finance, economics and the military

Since Caracalla created innumerable enemies through his terror, especially in the upper class, he was completely dependent on the army to maintain his power and on his Scythian and Germanic bodyguards for his personal safety . He won the support of the soldiers by greatly increasing their wages and frequently giving them generous special allowances ( donations ). The extent of the pay increase was 50 percent, with the already significantly increased pay by Septimius Severus forming the basis of calculation. According to an estimate communicated by Cassius Dio, the additional annual expenditure required was 280 million sesterces (70 million denarii ). This increase in military personnel costs was, however, financially disastrous. The preference for the military was only possible at the expense of the economically productive part of the population and the stability of the value of money, and generated immoderate expectations among the spoiled soldiers. Later rulers could no longer reverse this development without risking their immediate overthrow. Thus Caracalla set the course for the future military empire . His politics contributed to the fact that the developments referred to with the modern catchphrase " Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century " occurred later . Under him, problematic factors intensified, which heavily burdened the economy in the further course of the third century. However, serious structural problems existed even before he took office.

Caracalla divided up large provinces, probably to prevent a dangerous concentration of power in the hands of the provincial governors. No governor should have more than two legions under his command. He divided Britain into the two provinces of Britannia superior and Britannia inferior . In Hispania he separated from the great province of Hispania citerior or Tarraconensis a new province, which he called Hispania nova citerior Antoniniana . It was located in the northwest of the peninsula north of the Duero . Its existence can only be deduced from inscriptions and its extent is not exactly known, because it was reunited with the Tarraconensis by the thirties of the 3rd century at the latest.

Caracalla carried out a coin reform in 214/215, which should serve to finance the planned Parthian War. He created a new silver coin that was later referred to as the Antoninian after its official name, Antoninus . The antoninian, which became the most common Roman coin in the 3rd century, was equivalent to two denarii , but its weight was only about one and a half denarii. In fact, it was a question of a deterioration in money. This led to the hoarding of the old money, which can be seen from numerous treasure finds. In addition, the weight of the Aureus gold coin has been reduced by around 9 percent (from 7.20 to 6.55 g). As early as 212, Caracalla had reduced the silver content of the denarius by around 8 percent (from 1.85 g to 1.70 g), apparently because of the cost of the pay increases after Geta's murder. The monetary deterioration was even more drastic in the east of the empire, where the Syrian drachm and the tetradrachm lost half of their silver content (reduction from 2 g silver in 213 to 0.94 g in 217). This caused a massive loss of confidence in monetary value.

Despite the harshness with which Caracalla proceeded against any criticism, the tax burden is said to have led to a clear expression of displeasure in the crowd at a horse race.

religion

As Cassius Dio reports, Caracalla's relationship to religion was primarily determined by his need to obtain healing from his illnesses from the gods. For this purpose he is said to have offered sacrifices and offerings to all major deities and prayed diligently. The gods from whom he hoped for help included the Greek god of healing Asklepios , the Egyptian Sarapis and Apollon , who was identified with the Celtic god of healing Grannus and worshiped as Apollo Grannus. The emperor probably visited the Apollo Grannus temple in Faimingen , which was then called Phoebiana and belonged to the province of Raetia . He was especially venerated to Sarapis, in whose temple district he lived during his stay in Alexandria. On the Roman hill Quirinal he had a Sarapis temple built, which is attested in inscriptions but has not yet been localized.

Foreign policy

Germanic campaign

In the summer of 213 Caracalla undertook a brief campaign against Teutons. According to Byzantine excerpts from a lost part of Cassius Dio's historical work, it was about Alemanni . This is the first testimony of the Alemanni by name. The reliability of this statement, which was generally accepted in older research, has been repeatedly disputed since 1984, since the Alamann's name was only a later addition and did not come from Dio; But it still has supporters and is extensively defended against criticism. First, the emperor won a major victory on the Main, whereupon he took the victorious name Germanicus maximus . The battles that followed, however, seem to have turned out less favorably for him, because he was prompted to make payments to Germanic groups. Overall, however, his approach was apparently successful, because the situation on the northern border remained stable for two decades.

Expansion policy in the east

After the pacification of the northern border, Caracalla went to the east of the empire, from where he was no longer to return. At first he seems to have defeated the Carps in the area of the city of Tyras (today Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyj in southern Ukraine) , then he moved to Asia Minor . He spent the winter of 214/215 in Nicomedeia , from there he set out for Antioch in the spring of 215 . While he had previously placed himself in the footsteps of Alexander the great - he is said to have placed a chlamys , a ring and a belt on the sarcophagus when he visited Alexander's tomb - the imitation of Alexander reached its peak in the last years of his life . He is said to have set up a force of 16,000 men as a " Macedonian phalanx " with Macedonian clothing and armament. In a letter to the Senate, he claimed to be a reincarnation of the Macedonian king. With this he indicated the program of a restoration of Alexander's world empire, at least a glorious expansion to the east. Even before he set out for the east, he had King Abgar IX. lured by Osrhoene to Rome and imprisoned there, whereupon he annexed the kingdom. He had also cunningly brought the Arsakid king of Armenia and his family into his power, but in the kingdom of this ruler the Romans encountered stubborn resistance. A Roman advance into Armenia, the implementation of which the emperor had entrusted his confidante Theokritus, failed.

The connection to the model of Alexander the Great and his idea of world domination meant confrontation with the Parthian Empire, which Caracalla wanted to incorporate into the Roman Empire. Allegedly, he initially pursued his goal in a peaceful way or at least tried to create this impression: He is said to have proposed a marriage project to the Parthian king Artabanos IV . Artabanos was to give him his daughter to wife and thereby pave the way for a future unification of the two kingdoms. This project falls completely outside the framework of traditional Roman foreign policy; Roman emperors never entered into marriages with foreign rulers. The historicity of the episode communicated by Cassius Dio and Herodian, which Herodian embellished with fantastic elements, is disputed in scholarship; it is predominantly assumed that the tradition has at least a historical core. Alexander's example also played a role here; the Macedonian had Stateira , a daughter of the Persian king Dareios III. , got married. Only when Artabanos rejected the seemingly fantastic proposal did Caracalla begin the campaign against the Parthians in the spring of 216.

The Romans were favored by the fact that the Parthians were at that time a civil war between the brothers Artabanos IV. And Vologaeses VI. prevailed, in which, however, Caracalla's opponent Artabanos clearly had the upper hand. The Roman troops advanced to Arbela without a fight . There they plundered the tombs of the kings of the Adiabene , a dynasty dependent on the Parthian Empire. Then Caracalla retired to Edessa . There he spent the winter while Artabanos prepared the Parthian counterattack, which only then hit Caracalla's successor Macrinus with full force. Cassius Dio claims that the discipline of the Roman army was poor because of Caracalla's pampering of the soldiers.

Death and succession

Before fighting with the Parthians, Caracalla's rule came to a violent end. The detailed description of the prehistory and the circumstances of his death at Cassius Dio is considered credible in research, it is essentially adopted in modern representations.

The militarily inexperienced Praetorian prefect Macrinus was one of the people of non-senatorial origin who had brought Caracalla into key positions . As Cassius Dio reports, Macrinus found himself in an acute emergency in the spring of 217: prophecies had promised him the dignity of emperor, and Caracalla had heard of this; in addition, a written report was on the way to the emperor, and Macrinus had been warned of the consequent danger to his life. It was an intrigue, but the prefect had reason to see it as a deadly threat. Therefore he organized the murder of Caracalla with some dissatisfied people. Three men were involved in the attack: the evocatus Julius Martialis , who hated the emperor for a personal defection, and two Praetorian tribunes. Martialis carried out the assassination attempt on April 8, 217, when the emperor was on the way from Edessa to Carrhae , where he wanted to visit a famous sanctuary of the moon god Sin . When Caracalla got off his horse on the way to relieve himself, Martialis approached him, apparently to tell him something, and stabbed him in the back. A Scythian bodyguard Caracallas then killed the escaping assassin with his lance. The two praetorian tribunes rushed to the emperor, as if to help him, and completed the murder. With Caracalla, the male descendants of the dynasty founder Septimius Severus died out.

It was only after days of hesitation that the soldiers were persuaded to proclaim Macrinus emperor on April 11th. Caracalla was buried in the Hadriani mausoleum in Rome .

Appearance and iconography

According to Herodian, Caracalla was short in stature but sturdy. He preferred Germanic clothing and wore a blonde wig coiffed in the Germanic style. Cassius Dio mentions that the emperor liked to look wild.

The numerous sculptures that have survived give an idea of his appearance and, above all, of the impression he wanted to create. The coin portraits are also significant. Representations of the young Caracalla can hardly be distinguished from those of Geta. Numerous portraits from the time of his sole rule show the emperor with contracted forehead muscles and eyebrows; his willpower and willingness to use violence should be demonstrated with the grim expression. Apparently this self-portrayal was aimed at intimidation. At the same time the soldier qualities of the emperor should be emphasized.

Heinz Bernhard Wiggers distinguished five main types of round sculpture, which he mostly named after the location of the type-defining guide pieces. Later research followed him with regard to this grouping, but names and dates differently in some cases. The types are:

- “ Argentarian arch type ”, also known as the “first type of heir to the throne” (period approx. 197–204): Caracalla is shown partly as a child, partly as a teenager. He has thick, curly hair and still no beard. The type is very common. The forehead hairstyle is sometimes reminiscent of portraits of boys by Marcus Aurelius, whose fictional adoptive grandson was Caracalla.

- "Type Gabii", also called "second type of heir to the throne" or "consulate type" (period approx. 205–211): Caracalla is depicted as a young man with beard growth of varying degrees. A triangular forehead bulge with a point downwards and two horizontal forehead folds are new.

- “Vestalinnenhaus type”: This type was apparently not very common. The forehead bulge is flat, the horizontal forehead wrinkles are long; there are also two steep folds starting from the root of the nose. Wiggers dates the type to around 210; Klaus Fittschen puts its creation in the time of Caracalla's sole rule.

- "First autocratic type" (Fittschen) or "autocratic type" (Wiggers): This type, probably created in 212, is very common, it is the characteristic type of portrait of the autocratic period and was often imitated in the early modern period. The hair is arranged in rows of curls. The facial expression is tense. In addition to the horizontal and vertical forehead creases, there are two diagonal creases that laterally delimit the forehead bulge. Wrinkled, drawn-together brows add to the sinister impression that wrinkled forehead creates. A pinch fold at the root of the nose is new. A variant with a curved nose occurs only in finds from the east; presumably this is a realistic aspect that the urban Roman sculptors omitted for aesthetic reasons.

- "Second autocratic type" (Fittschen) or "Tivoli type" (Wiggers): The facial features are significantly more relaxed than with the first autocratic type. Wiggers dated this type to around 211–214, Fittschen - whose view has prevailed - put it in the year 215.

More types of portraits can be distinguished on coins, which is probably due to the better location of the coins compared to the plastic. The first type shows Caracalla as a childish Caesar without a laurel wreath. This is followed by six types from the period between 197 and the Geta assassination at the end of 211, distinguishable by their increasing beard. According to the father's wishes, the coin portraits were supposed to emphasize the similarity of the two brothers and thus present them as future successors with equal rights. After Geta's death, the eighth portrait type followed, characterized by dramatic forehead wrinkles, and finally, in the final years of government, the ninth and last type with more relaxed facial features. These two types correspond to the first and second monopoly types of sculpture.

reception

Contemporary judgments and representation in the main sources

Caracalla's reputation with the soldiers was based not only on his financial generosity, but also on his closeness to their way of life: on the campaigns he voluntarily undertook the same hardships as a common soldier. His physical stamina earned him respect. Its popularity in the army continued long after his death. Perhaps already during Macrinus' brief reign, the soldiers managed to get the Senate reluctantly elevated him to god as part of the imperial cult . At the latest from the first year of the reign of Macrinus' successor Elagabal , he was revered as divus Magnus Antoninus . Elagabal owed his rise to power to the fact that he was passed off as the illegitimate son of Caracalla, which earned him the sympathy of the soldiers; in reality he was only very distantly related to the murdered emperor. Elagabal's successor Severus Alexander also appeared as the illegitimate son of Caracalla in order to make himself popular with the soldiers.

The news of Caracalla's standing among the metropolitan population is contradicting itself. He was hated in the Senate, so his death was cheered there. Since he could not rely on the senatorial families, he relied on climbers of knightly origin. Their preference increased the bitterness of the deposed senators.

The extremely caracalla-hostile mood in the senatorial ruling class is reflected in the main sources, the representations of the contemporary historians Cassius Dio and Herodian , as well as in the Historia Augusta, which was created much later and is less valuable as a source . Cassius Dio thought Caracalla was deranged. He interpreted almost everything the emperor did to his disadvantage. His Roman history , written from the perspective of the senatorial opposition, is considered the best source and relatively reliable despite this very partisan attitude. However, the part of this work dealing with Caracalla's time has only survived in fragments; it has been preserved mainly in excerpts, which reproduce the text in a greatly abbreviated form and in part paraphrased. Herodian's story of the empire after Marcus Aurelius has been preserved in the original. He probably used Dio's work, but the relationship between the two sources is unclear and controversial. The source value of Herodian's account is estimated to be much lower than that of Dios Roman History . The Late Antique Historia Augusta depends in part on the two older works, but its author must also have had access to material from at least one other source that is now lost.

Outside the circle of his followers, the emperor was nicknamed. It was probably not until the time of his sole rule that he was called Caracalla after his hooded coat . It was a modified luxury version of a Celtic garment designed personally by the emperor. Another nickname that Cassius Dio passed down was Tarautas ; A short, ugly and brutal gladiator was known by this name, who apparently looked similar to the emperor, at least in the opinion of his opponents.

Ancient Caracalla Legends

Even during Caracalla's lifetime, rumors apparently circulated about a sexual relationship between him and his mother Julia Domna after his father's death. This was a calumny that over time grew into a legend. The 354 chronograph communicates it like a fact. In reality, the mother and son relationship was bad after Geta's murder, even though Julia Domna was officially honored. Incest was a topos of the portrayal of tyrants and was already subordinated to Nero .

Sources from the 4th century and later, including the Historia Augusta , Aurelius Victor , Eutropius and the Epitome de Caesaribus , make Julia Domna the stepmother Caracallas and claim that he married her. This fantastic representation can also be found in Christian authors of the patristic time ( Orosius , Hieronymus ) and shaped the image of Caracalla as an unrestrained monster in the Middle Ages. The actual fratricide of Geta, however, was forgotten.

middle Ages

A medieval Caracalla legend tells Geoffrey of Monmouth , who wrote the historical work De gestis Britonum in the 12th century , which later became known under the title Historia regum Britanniae and had a very strong aftermath. According to Geoffrey's account, Geta and Caracalla, whom he calls Bassianus, were only half-brothers; Geta was from a Roman mother, Caracalla from a British mother. Caracalla was elected king by the British, since he belonged to them on his mother's side, Geta by the Romans. The battle came in which Caracalla was victorious and Geta was killed. Later Caracalla was defeated and killed by Carausius . In this representation Geoffrey mixed up different epochs, because in reality Carausius was a Roman commander who had himself proclaimed emperor in 286 and founded a short-lived special empire in Britain and northern coastal areas of Gaul.

Early modern age

At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, an unknown English poet wrote the Latin university drama Antoninus Bassianus Caracalla in iambic senars . In addition to the fratricide, he particularly addressed the alleged marriage of Caracallas to Julia Domna, depicting Julia not as a stepmother but as Caracallas' birth mother. So he described the connection as real incest .

In 1762 the French painter Jean-Baptiste Greuze made an oil painting showing Septimius Severus and Caracalla in Britain. The emperor accuses his son of trying to murder him. The scene is based on a legendary tradition shared by Cassius Dio, according to which Caracalla was confronted but not punished after an attempted assassination on his father.

Modern

The assessments of modern historians are generally based - despite criticism of details of the tradition - largely on the Caracalla image of ancient historiography. In older research, Caracalla was used to be a typical representative of a period of decay. Cassius Dio's unverifiable assertion that the emperor was insane continues to have an impact today. The previously popular catchphrase Caesarean madness is avoided in the specialist literature, as it is unscientific and does nothing to illuminate historical reality.

Two leading art historians of the 19th century, Anton Springer and Jacob Burckhardt , believed that Caracalla's portrait was profoundly criminal.

For Theodor Mommsen Caracalla was "a petty, worthless person who made himself as ridiculous as it was contemptible"; His “insane lust for fame” prompted him to participate in the Parthian War and he “fortunately” died in the process. Ernst Kornemann wrote that he was "full of megalomania"; in the army and in the state "the common, ignorant crowd" ruled everywhere. Alfred Heuss said that Caracalla was incapable of “objective achievements”, “a raw, unrestrained and morally inferior person, who even before he ascended the throne betrayed strong criminal tendencies”; he was led to the Parthian War by his “childish imagination”. Karl Christ's verdict was similar : Caracalla did not hide his “cruelty, deceit and inner instability”, suffered from a nervous disease and reacted “extremely and overwrought in every respect”. He was "brutal, of uncanny willpower"; in the anecdotes that have been handed down, “the historical truth is probably condensed”. Above all, he wanted to arouse fear with his self-portrayal. In retrospect, the Constitutio Antoniniana appears to be an important measure, but has hardly changed the existing structures politically. Géza Alföldy was of the opinion that the judgment of Cassius Dios was "basically correct", that Caracallas "saved his honor" was completely unfounded.

In recent research, however, it is also emphasized that the contemporary narrative sources come from passionate opponents of the emperor and reflect the attitude of the opposition Senate circles and that exaggerations are to be expected in the descriptions of his misdeeds, his repulsive character traits and his unpopularity. It should be noted that Caracalla was possibly less hated by large parts of the imperial population than by the upper class of the capital. It is undisputed that he was held in the highest esteem by the soldiers even long after his death. Anthony R. Birley thinks that one should take Cassius Dio's bias into account, but little can be said to exonerate Caracalla.

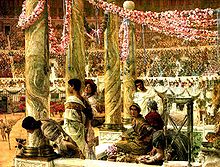

In 1907, after almost two years of work , Lawrence Alma-Tadema completed the oil painting "Caracalla and Geta". It shows the imperial family - Caracalla with his brother and parents - in the Colosseum .

Source editions and comments

- Herbert Baldwin Foster , Earnest Cary (Ed.): Dio's Roman History , Volume 9, Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1961 (reprint of 1927 critical edition)

- Peter Alois Kuhlmann (ed.): The Giessen literary papyri and the Caracalla edicts. Edition, translation and commentary (= reports and works from the University Library and the University Archive Gießen , Vol. 46). University Library Gießen, Gießen 1994, pp. 215–255 (contains: Constitutio Antoniniana ; The Amnesty Decree ; The Expulsion of the Egyptians from Alexandria . Digitized )

- Carlo M. Lucarini (Ed.): Herodianus: Regnum post Marcum . Saur, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-598-71282-0 (critical edition)

- Michael Louis Meckler (Ed.): Caracalla and his late-antique biographer: a historical commentary on the Vita Caracalli in the Historia Augusta . Dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 1994 (introduction, critical edition, English translation and commentary)

literature

General

- Julia Gräf (Ed.): Caracalla. Emperor, tyrant, general. Von Zabern, Darmstadt / Mainz 2013, ISBN 978-3-8053-4611-5 (illustrated book; collection of articles by several authors)

- David S. Potter: The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395 . London / New York 2004, ISBN 0-415-10057-7 , pp. 110-124, 133-151

- Ilkka Syvänne: Caracalla. A Military Biography. Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley 2017, ISBN 978-1-4738-9524-9

- Gerhard Wirth : Caracalla in Franconia. To realize a political ideology . In: Jahrbuch für Fränkische Landesforschung 34/35, 1975, pp. 37-74 (also contains a general study of Caracalla's rule)

iconography

- Klaus Fittschen , Paul Zanker : Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome . Volume 1, 2nd, revised edition, Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-0596-6 , text volume pp. 98–100, 102–112, table volume Tafeln 105–116 (No. 86, 88–94)

- Heinz Bernhard Wiggers, Max Wegner : Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla. Macrinus to Balbinus (= Max Wegner (Hrsg.): The Roman image of rulers , section 3, volume 1). Gebrüder Mann, Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-7861-2147-8 , pp. 9-92

Tools

- Attilio Mastino: Le titolature di Caracalla e Geta attraverso le iscrizioni (indici) . Editrice Clueb, Bologna 1981 (compilation of the inscribed evidence for the title)

Web links

- Michael L. Meckler: Short biography (English) at De Imperatoribus Romanis (with references).

- Literature by and about Caracalla in the catalog of the German National Library

- English translation of the biography in the Historia Augusta by LacusCurtius

Remarks

- ↑ The gentile name Aurellius (instead of Aurelius ) is almost consistently used for Caracalla (as also later for Elagabal and Severus Alexander) in formal, solemn inscriptions and is also the rule otherwise, cf. Werner Eck , Hans Lieb: A diploma for the Classis Ravennas of November 22, 206 , in: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 96, 1993, pp. 75–88 ( PDF; 3.8 MB ), here p. 79, note 16 .

- ↑ It has been suspected that it was Caracalla's portrait rather than Geta's that was accidentally deleted; see Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla . In: Max Wegner (Ed.): Das Roman Herrscherbild , Division 3 Volume 1, Berlin 1971, pp. 9–129, here: 48. This hypothesis, however, did not prevail; see Florian Krüpe: Die Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, p. 237.

- ↑ For the date see Géza Alföldy: Nox dea fit lux! Caracalla's birthday . In: Giorgio Bonamente, Marc Mayer (eds.): Historiae Augustae Colloquium Barcinonense , Bari 1996, pp. 9–36, here: 31–36.

- ^ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 9.3. When specifying some of the books of Cassius Dio's work, different counts are used; a different book count is given here and below in brackets.

- ↑ Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 4f.

- ↑ Historia Augusta , Caracalla 1,3-2,1.

- ^ Helga Gesche : The divinization of the Roman emperors in their function as legitimation of rule . In: Chiron 8, 1978, pp. 377-390, here: 387f .; Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 9 and note 34; Anne Daguet-Gagey: Septime Sévère , Paris 2000, pp. 255f .; Drora Baharal: Victory of Propaganda , Oxford 1996, pp. 20-42.

- ↑ Florian Krüpe: The Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, p. 182f. and note 48.

- ^ For spring 196, Matthäus Heil pleads : Clodius Albinus and the civil war of 197 . In: Hans-Ulrich Wiemer (Ed.): Statehood and Political Action in the Roman Empire , Berlin 2006, pp. 55–85, here: 75–78. Helmut Halfmann , among others, has a different opinion : Itinera principum , Stuttgart 1986, p. 220; he advocates mid-195.

- ↑ Michael Meckler: Caracalla the Intellectual . In: Enrico dal Covolo, Giancarlo Rinaldi (ed.): Gli imperatori Severi , Rom 1999, pp. 39-46, here: 44f.

- ↑ Zeev Rubin advocates dating before the end of 197: Dio, Herodian, and Severus' Second Parthian War . In: Chiron 5, 1975, pp. 419-441, here: 432-435. Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 10 advocates the date January 28, 198.

- ^ Cassius Dio 77 (76), 3-6. On these events, see Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, pp. 137, 143f., 161f .; Barbara Levick : Julia Domna , London 2007, pp. 74–81.

- ↑ Illustration in Barbara Levick: Julia Domna , London 2007, p. 81. Cf. Daría Saavedra-Guerrero: El poder, el miedo y la ficción en la relación del emperador Caracalla y su madre Julia Domna . In: Latomus 66, 2007, pp. 120-131, here: 122f.

- ↑ Florian Krüpe: Die Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, p. 183 and note 52.

- ↑ For the dating see Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, p. 274; Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 13, note 58.

- ↑ Herodian 3:15, 2 with details; Cassius Dio restricts himself to a general reference, see Cassius Dio 77 (76), 15.2 (cf. 77 (76), 14.1–7).

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: Septimius Severus. The African Emperor , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, pp. 179-188; Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, pp. 80–82.

- ↑ See Henning Börm : Born to Be Emperor. The Principle of Succession and the Roman Monarchy. In: Johannes Wienand (Ed.): Contested Monarchy , Oxford 2015, pp. 239–264, here: 241–243.

- ↑ Herodian 4,3,5-9.

- ↑ Barbara Levick: Julia Domna , London 2007, pp. 87f .; Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, p. 62f .; Géza Alföldy: The Crisis of the Roman Empire , Stuttgart 1989, pp. 190–192. See Julie Langford: Maternal Megalomania , Baltimore 2013, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Investigating the attitude of the troops Jenö Fitz : The behavior of the army in the controversy between Caracalla and Geta . In: Dorothea Haupt, Heinz Günter Horn (eds.): Studies on the military borders of Rome , Vol. 2, Bonn 1977, pp. 545–552, and Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, pp. 105–110 .

- ↑ For the dating see Anthony R. Birley: Septimius Severus. The African Emperor , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, p. 189; Helmut Halfmann: Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 229f .; Géza Alföldy: The Crisis of the Roman Empire , Stuttgart 1989, p. 179; Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, pp. 15, 109-112; Florian Krüpe: The Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, p. 13, 195–197

- ^ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 2.2-4. Cf. Géza Alföldy: The Crisis of the Roman Empire , Stuttgart 1989, pp. 193–195.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 23.3.

- ↑ For the extraordinary consistency in the implementation, see Florian Krüpe: Die Damnatio memoriae. About the destruction of memories. A case study on Publius Septimius Geta (198–211 AD) , Gutenberg 2011, pp. 14–16.

- ^ See on the speech by Florian Krüpe: Die Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, pp. 188f .; on the amnesty David S. Potter: The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395 , London 2004, p. 136.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 3: 1-2; Herodian 4,4.7-5.1. Cf. Michael Alexander Speidel: Heer und Herrschaft in the Roman Empire of the High Imperial Era , Stuttgart 2009, p. 415; Robert Develin: The Army Pay Rises under Severus and Caracalla and the Question of Annona militaris . In: Latomus 30, 1971, pp. 687–695, here: p. 687 and note 6.

- ↑ Historia Augusta , Caracalla 2,6–8 and Geta 6,1–2. See Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, pp. 115-117; Markus Handy: The Severers and the Army , Berlin 2009, p. 105f. and note 38; Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, p. 32, 64; David S. Potter: The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395 , London 2004, pp. 135f.

- ^ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 4.1.

- ↑ Janet Montgomery et al .: Identifying the origins of decapitated male skeletons from 3 Driffield Terrace, York, through isotope analysis: reflections of the cosmopolitan nature of Roman York in the time of Caracalla. In: Michelle Bonogofsky (Ed.): The Bioarchaeology of the Human Head: Decapitation, Decoration and Deformation , Gainesville 2011, pp. 141–178.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 4, 1-2. For individual victims, see Shamus Sillar: Caracalla and the senate: the aftermath of Geta's assassination. In: Athenaeum 89, 2001, pp. 407-423; Björn Schöpe: The Roman imperial court in Severan times (193–235 AD) , Stuttgart 2014, pp. 109–111; Danuta Okoń: Imperatores Severi et senatores. The History of the Imperial Personnel Policy , Szczecin 2013, pp. 25-30, 55-58.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 17: 1-2; see. Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, p. 65f.

- ^ Karlheinz Dietz : Caracalla, Fabius Cilo and the Urbaniciani . In: Chiron 13, 1983, pp. 381-404, here: 397-403; Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, pp. 32f., 64f., 113f .; Frank Kolb : Literary relationships between Cassius Dio, Herodian and the Historia Augusta , Bonn 1972, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 22-23. See Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprising and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, pp. 34f., 159–166; Drora Baharal: Caracalla and Alexander the Great: a Reappraisal . In: Carl Deroux (Ed.): Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History , Vol. 7, Bruxelles 1994, pp. 524-567, here: 529. Cf. Frank Kolb: Literary Relationships between Cassius Dio, Herodian and the Historia Augusta , Bonn 1972, pp. 97-111; Agnès Bérenger-Badel: Caracalla et le massacre des Alexandrins: entre histoire et légende noire . In: David El Kenz (ed.): Le massacre, objet d'histoire , Paris 2005, pp. 121-139.

- ↑ Herodian 4, 6, 4-5. See Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, pp. 33, 115.

- ↑ See for this building Nele Schröder : A major Severan project: The equipment of the Caracalla baths in Rome . In: Stephan Faust, Florian Leitmeir (eds.): Forms of Representation in Severan Time , Berlin 2011, pp. 179–192.

- ↑ Hartmut Wolff offers a comprehensive study : The Constitutio Antoniniana and Papyrus Gissensis 40 I , 2 volumes, Cologne 1976; on the question of the private law consequences of granting citizenship, see Vol. 1, pp. 80-109. The more recent research is processed by Kostas Buraselis : Theia Dorea. The divine imperial gift. Studies on the politics of the Severer and the Constitutio Antoniniana , Vienna 2007.

- ↑ Hartmut Wolff: The Constitutio Antoniniana and Papyrus Gissensis 40 I , Vol. 1, Cologne 1976, pp. 278–281.

- ↑ Peter Alois Kuhlmann (Ed.): The Giessen literary papyri and the Caracalla edicts. Edition, translation and commentary , Gießen 1994, p. 222f. (Greek text and translation), 225f. (Comment).

- ↑ Janken Kracker, Markus Scholz : On the reaction to the Constitutio Antoniniana and the scope of the granting of citizenship based on the imperial surname Aurelius . In: Barbara Pferdehirt , Markus Scholz (Ed.): Citizenship and Crisis. The Constitutio Antoniniana 212 AD and its domestic political consequences (= mosaic stones. Research at the Roman-Germanic Central Museum. Volume 9), Mainz 2012, pp. 67–75.

- ↑ Herodian 4,4,7.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 36.3. On the pay increase, see Robert Develin: The Army Pay Rises under Severus and Caracalla and the Question of Annona militaris . In: Latomus 30, 1971, pp. 687-695, here: 687-692; Michael Alexander Speidel: Army and Rule in the Roman Empire of the High Imperial Era , Stuttgart 2009, p. 350, 415.

- ^ Julia Sünskes Thompson: uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, p. 60f .; Michael Alexander Speidel: Army and Rule in the Roman Empire of the High Imperial Era, Stuttgart 2009, pp. 415, 436f.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, pp. 190f.

- ↑ David R. Walker: The Metrology of the Roman Silver Coinage , Part 3, Oxford 1978, pp. 62-64, 100, 130-132; Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 27.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 10.3. See Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprising and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, pp. 33, 114f.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 15: 3-7.

- ↑ Gerhard Weber: To the veneration of Apollo Grannus in Faimingen, to Phoebiana and Caracalla . In: Johannes Gehartner , Pia Eschbaumer, Gerhard Weber: Faimingen-Phoebiana , Volume 1: The Roman Temple District in Faimingen-Phoebiana , Mainz 1993, pp. 122–136, here: p. 133 and note 609.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 23.2.

- ^ Lawrence Richardson Jr .: A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome , Baltimore 1992, p. 361.

- ↑ For the chronology and the course of the campaign see Andreas Hensen: Zu Caracallas Germanica Expeditio. Archaeological-topographical investigations . In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg 19/1, 1994, pp. 219-254.

- ↑ Bruno Bleckmann pleads for credibility : The Alamanni in the 3rd century: Ancient historical remarks on the first mention and on ethnogenesis . In: Museum Helveticum 59, 2002, pp. 145–171, here: 147–153, 170. John F. Drinkwater follows his view: The Alamanni and Rome 213–496 (Caracalla to Clovis) , Oxford 2007, p. 43f. , and Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, pp. 82–87. Opposite opinions are among others Dieter Geuenich : History of the Alemannen , 2nd, revised edition, Stuttgart 2005, S. 18f., And Helmut Castritius : From political diversity to unity. On the ethnogenesis of the Alemanni . In: Herwig Wolfram , Walter Pohl : Types of Ethnogenesis with Special Consideration of Bavaria , Part 1, Vienna 1990, pp. 71–84, here: 73–75. The hypothesis that the Alemannic name was not in Cassius Dio's original text had already been put forward in 1984 by Matthias Springer and Lawrence Okamura, who came to this conclusion independently of one another. Camilla Dirlmeier, Gunther Gottlieb (ed.): Sources for the history of the Alamanni from Cassius Dio to Ammianus Marcellinus , Sigmaringen 1976, pp. 9–12, provide a compilation of the sources on the early Alemanni (with translation) . See Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, pp. 141f.

- ↑ Therefore, u. a. Peter Kneißl : The victory statute of the Roman emperors , Göttingen 1969, p. 160f. Gerhard Wirth has a similar judgment: Caracalla in Franconia. To realize a political ideology . In: Yearbook for Fränkische Landesforschung 34/35, 1975, pp. 37-74, here: 66, 68f.

- ↑ Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 146; Boris Gerov: The Carpen Invasion in 214 . In: Acta of the Fifth International Congress of Greek and Latin Epigraphy, Cambridge 1967 , Oxford 1971, pp. 431-436. But see Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, p. 88.

- ^ For the route, see Helmut Halfmann: Itinera principum , Stuttgart 1986, pp. 227–229.

- ↑ Herodian 4,8,9.

- ↑ On the entire phenomenon see Angela Kühnen: Die imitatio Alexandri in der Romanpolitik, Münster 2008, pp. 176–186, 192; Disagrees with the political intent of Caracalla Drora Baharal: Caracalla and Alexander the Great: a Reappraisal . In: Carl Deroux (Ed.): Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History , Vol. 7, Bruxelles 1994, pp. 524-567. Cf. Kostas Buraselis: ΘΕΙΑ ΔΩΡΕΑ , Vienna 2007, pp. 29–36.

- ↑ See Drora Baharal: Caracalla and Alexander the Great: a Reappraisal . In: Carl Deroux (Ed.): Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History , Vol. 7, Bruxelles 1994, pp. 524-567, here: 529f.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 7.2. For the authenticity of the letter, see Drora Baharal: Caracalla and Alexander the Great: a Reappraisal . In: Carl Deroux (Ed.): Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History , Vol. 7, Bruxelles 1994, pp. 524–567, here: p. 530 and note 9.

- ↑ See on Caracalla's plans for Armenia Lee Patterson: Caracalla's Armenia . In: Syllecta Classica 24, 2013, pp. 173-199.

- ↑ On these events and their chronology see André Maricq: Classica et Orientalia , Paris 1965, pp. 27–32.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 1.1; Herodian 4: 10-11. Count on a historical core u. a. Karl Christ: History of the Roman Imperial Era, 6th edition, Munich 2009, p. 623f., Karl-Heinz Ziegler : Relations between Rome and the Parthian Empire , Wiesbaden 1964, p. 133, Gerhard Wirth: Caracalla in Franconia. To realize a political ideology . In: Jahrbuch für Fränkische Landesforschung 34/35, 1975, pp. 37-74, here: 55-58 and Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, pp. 30f. Dieter Timpe has a different opinion : A marriage plan for Emperor Caracallas . In: Hermes 95, 1967, pp. 470-495. Joseph Vogt turns against Timpe's argument : To Pausanias and Caracalla . In: Historia 18, 1969, pp. 299-308, here: 303-308.

- ↑ On the course of the campaign see Erich Kettenhofen : Caracalla . In: Encyclopædia Iranica , Vol. 4, London 1990, pp. 790-792, here: 791 ( online ).

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 3, 4–5 (cf. 79 (78), 1, 3–4). Cf. Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, p. 66.

- ↑ See for example Karl Christ: Geschichte der Roman Kaiserzeit , 6th edition, Munich 2009, pp. 625f .; Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, p. 66f.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 4.1-5.2.

- ↑ Doubts about the role of Macrinus as the organizer of the conspiracy are unjustified; see Frank Kolb: Literary Relationships between Cassius Dio, Herodian and the Historia Augusta , Bonn 1972, p. 133, note 647.

- ↑ See on Caracalla's planned visit to the sanctuary Frank Kolb: Literary Relationships between Cassius Dio, Herodian and the Historia Augusta , Bonn 1972, p. 123f.

- ^ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 5: 2-5. See Herodian 4:13 and Historia Augusta , Caracalla 6,6–7,2. See also Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, pp. 152-156.

- ↑ Herodian 4,7 and 4,9,3. Cf. Cassius Dio 79 (78), 9.3: The gladiator Tarautas compared to Caracalla was also small.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 11.1.

- ^ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Empire , 6th edition, Munich 2009, p. 625; Anne-Marie Leander Touati: Portrait and historical relief. Some remarks on the meaning of Caracalla's sole ruler portrait . In: Anne-Marie Leander Touati u. a. (Ed.): Munuscula Romana , Stockholm 1991, pp. 117-131, here: 129f .; Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla . In: Max Wegner (Ed.): The Roman Empire, Division 3 Volume 1, Berlin 1971, pp. 9–129, here: 11.

- ↑ Anne-Marie Leander Touati: Portrait and historical relief. Some remarks on the meaning of Caracalla's sole ruler portrait . In: Anne-Marie Leander Touati u. a. (Ed.): Munuscula Romana , Stockholm 1991, pp. 117-131.

- ^ Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla . In: Max Wegner (Ed.): Das Roman Herrscherbild , Division 3 Volume 1, Berlin 1971, pp. 9–129, here: 17–35; Klaus Fittschen, Paul Zanker: Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Mainz 1994, text volume pp. 98–100, 102–112; Florian Leitmeir: Breaks in the emperor's portrait from Caracalla to Severus Alexander . In: Stephan Faust, Florian Leitmeir (eds.): Forms of Representation in Severan Time , Berlin 2011, pp. 11–33, here: 13–18.

- ^ Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla . In: Max Wegner (ed.): Das Roman Herrscherbild , Department 3 Volume 1, Berlin 1971, pp. 9–129, here: 25f., 52; Klaus Fittschen, Paul Zanker: Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Mainz 1994, text volume p. 111.

- ^ Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla . In: Max Wegner (Ed.): Das Roman Herrscherbild , Department 3 Volume 1, Berlin 1971, pp. 9–129, here: 33f.

- ^ Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla . In: Max Wegner (ed.): Das Roman Herrscherbild , Division 3 Volume 1, Berlin 1971, pp. 9–129, here: 26; Klaus Fittschen, Paul Zanker: Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome , Volume 1, 2nd edition, Mainz 1994, text volume p. 110f. Fittschen's view follows Florian Leitmeir: Breaks in the portrait of the emperor from Caracalla to Severus Alexander . In: Stephan Faust, Florian Leitmeir (eds.): Forms of Representation in Severan Time , Berlin 2011, pp. 11–33, here: 17f.

- ↑ Andreas Pangerl: Portrait types of Caracalla and Geta on Roman Empire coins - definition of a new Caesar type of Caracalla and a new Augustus type of Geta. In: Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt des RGZM Mainz 43, 2013, pp. 99–116.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 11.2-3; 78 (77), 13: 1-2; Herodian 4,7,4-7; 4.13.7. Cf. Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, p. 67.

- ↑ On this cult and the date of its introduction see James Frank Gilliam : On Divi under the Severi. In: Jacqueline Bibauw (Ed.): Hommages à Marcel Renard , Vol. 2, Bruxelles 1969, pp. 284–289, here: 285f .; Helga Gesche: The divinization of the Roman emperors in their function as legitimation for rule . In: Chiron 8, 1978, pp. 377-390, here: 387f.

- ↑ Helmut Halfmann: Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 232-234.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 15: 2-3.

- ↑ For an assessment of the sources, see Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprising and protest actions in the Roman Empire. The Severan emperors in the field of tension in domestic political conflicts , Bonn 1990, p. 11 and the literature mentioned there. See Friedhelm L. Müller (ed.): Herodian: Geschichte des Kaisertums after Marc Aurel , Stuttgart 1996, pp. 21-23.

- ↑ Helmut Halfmann: Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 231.

- ↑ On the garment caracalla and the nickname of the emperor derived from it, see Johannes Kramer: On the meaning and origin of caracalla . In: Archive for Papyrus Research and Related Areas 48, 2002, pp. 247–256.

- ^ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 9.3.

- ↑ Chronograph von 354, ed. by Theodor Mommsen, Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Auctores antiquissimi , vol. 9 (= Chronica minora , vol. 1), Berlin 1892, p. 147 (on Antoninus Magnus ).

- ↑ See on the legend Barbara Levick: Julia Domna , London 2007, pp. 98f .; Gabriele Marasco: Giulia Domna, Caracalla e Geta: frammenti di tragedia alla corte dei Severi . In: L'Antiquité Classique 65, 1996, pp. 119-134, here: 119-126.

- ↑ See on this version of the legend Gabriele Marasco: Giulia Domna, Caracalla e Geta: frammenti di tragedia alla corte dei Severi . In: L'Antiquité Classique 65, 1996, pp. 119-134, here: 126-134.

- ↑ Geoffrey von Monmouth, De gestis Britonum ( Historia regum Britanniae ) 5,74f., Edited and translated into English by Michael D. Reeve and Neil Wright: Geoffrey of Monmouth: The History of the Kings of Britain , Woodbridge 2007, p. 90 -93.

- ↑ Edited, translated into German and commented by Uwe Baumann: Antoninus Bassianus Caracalla , Frankfurt am Main 1984.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 77 (76), 14.3-7.

- ↑ Michael Meckler: Caracalla the Intellectual . In: Enrico dal Covolo, Giancarlo Rinaldi (ed.): Gli imperatori Severi , Rom 1999, pp. 39-46, here: 40f.

- ^ Theodor Mommsen: Römische Kaisergeschichte , Munich 1992, p. 396f.

- ^ Ernst Kornemann: Römische Geschichte , Vol. 2, 6th edition, Stuttgart 1970, p. 311f.

- ↑ Alfred Heuss: Roman History , 10th edition, Paderborn 2007, p. 358f. (1st edition 1960).

- ^ Karl Christ: History of the Roman Imperial Era, 6th edition, Munich 2009, pp. 622–625.

- ^ Géza Alföldy: The Crisis of the Roman Empire , Stuttgart 1989, p. 209.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: Caracalla . In: Manfred Clauss (Ed.): The Roman Emperors. 55 historical portraits from Caesar to Justinian , 4th edition, Munich 2010, pp. 185–191, here: 191; Drora Baharal: Caracalla and Alexander the Great: a Reappraisal . In: Carl Deroux (Ed.): Studies in Latin Literature and Roman History , Vol. 7, Bruxelles 1994, pp. 524–567, here: 564.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, p. 189.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Septimius Severus |

Roman emperor 211–217 |

Macrinus |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Caracalla |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lucius Septimius Bassianus; Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus; Marcus Aurellius Severus Antoninus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Roman emperor (211-217) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 4, 188 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lugdunum |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 8, 217 |

| Place of death | Mesopotamia |