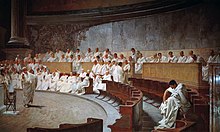

Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( Latin senatus , derived from senex "old man, elder") was the most important institution of the Roman state until the end of the republic . Not only the Senate as a body was responsible for this importance, also its members, the Senators, were always important and generally recognized persons in the Reich . Although the rights of the Senate, which was primarily an assembly of former officials, and the legal force of its decisions were never written down, it determined Roman politics up to the time of Augustus and in exceptional situations afterwards. The Senate existed until the end of late antiquity .

History of the Roman Senate

The Senate in royalty

Information about the Senate at the time when Rome was supposedly still ruled by kings is sparse; all sources are from a much later period, and much is therefore very controversial among ancient historians . Sometimes it is even doubted that it even existed back then. At that time the body probably corresponded to a privy councilor who advised the king on his policy, but had no possibility of action itself; It is also conceivable, however, that it was a meeting of the heads of the large families who, at least in part, were fundamentally in opposition to the king. The assertion of many later ancient authors that the legendary city founder Romulus convened the first senate, as well as the existence of Romulus, must be questioned; The historicity of the other Roman kings is also controversial. If there never was a real kingship in Rome, then of course the early Senate cannot have been a privy councilor.

One thing is certain: the establishment of a council was typical of most ancient city-states - Athens, Sparta, Carthage and numerous other communities also knew comparable bodies; the existence of a monarchy was therefore not a prerequisite for the existence of a council. According to Cicero (who lived much later), the early Roman Senate, which initially had hardly more than 100 members, was composed of senes , i.e. older and experienced men, and above all the patres , the heads of respected Roman families. This is where the term senatus comes from , meaning “council of elders” or “council of elders”. In addition to the advisory function, the senators also provided interrex , the chief administrator for the period between the death of the previous king and the election of a new king.

In addition, the tasks of the Senate were presumably largely of a sacred nature. It was only under King Tarquinius Priscus , who supposedly expanded the Senate by a hundred members, that he gradually gave up this function under Greek influence; like all traditions about the early Roman period, this could also be a later construction.

The Senate in the Republic

After the end of the royal era, the Senate took on a role in the legislative process and in government in what was still little Rome. In the system of magistrates that soon emerged, the Senate was the only institution that really lasted - after all, officials were re-elected every year. Outward signs of the importance of the senators were a broad purple stripe (latus clavus) on the tunic and a gold signet ring (symbolum).

composition

The composition of the Senate, which had grown to around 300 members through the admission of Sabines and Etruscans , was determined by drawing up the list of the Senate (lectio senatus) , a task that fell under the responsibility of the supreme magistrate for most of the Roman Republic , first of the praetor maximus and until 313 BC The consuls , then the censors . However, these were not allowed to arbitrarily appoint senators, but were tied to the traditional customs (mores) of the republic. Above all, these stated that a member of the Senate should have completed at least part of the cursus honorum , the traditional official career. For a senate resolution to be possible and valid, at least a hundred senators had to be present - a sign that many members rarely entered the curia and only on important occasions . Until the quorum was reached, the senators gathered in a place called senaculum .

The entry threshold has been lowered over the centuries. Initially only former praetors and consuls - only these offices were endowed with an imperium , i.e. military command - had a right to be admitted to the Senate, but this had been in effect since the end of the 3rd century BC. BC also for the curular aediles , since the end of the 2nd century BC. For the tribunes and plebeian aediles and since 81 BC Already for the quaestors . The former consuls - usually around 30 people - dominated the committee and had the highest reputation ( auctoritas ); they and their direct descendants formed the core of the nobility . Over two-thirds of the senators, on the other hand, did not even reach the praetur, so their opinion usually had little weight. Since the Senate list was drawn up in the high republic during the censorship period, i.e. usually only every five years, former incumbents usually had to wait a few years before they officially became senators (qui in senatu sunt) . In the meantime they had a special status and were allowed to express their opinion in the Senate (quibus in senatu sententiam dicere licet) . Exceptionally, however, individual persons could also be admitted to the Senate because they appeared to the responsible magistrate to be worthy of it (optimus quisque) , even if they had not yet held a public office. Conversely, former officials who, according to tradition, would have had a seat in the Senate, could be overlooked if they were perceived as unworthy. It was only after Sulla's reforms in the late republic that civil servants entered the Senate automatically and immediately after their term of office had expired - that is, since the cursus honorum was established at the same time, usually after the bursary. From 81 BC The role of the censors in the compilation of the Senate list (however, a censor could still exclude "unworthy" senators). At the same time, the Senate was expanded to 600 members under Sulla. Later Gaius Iulius Caesar temporarily increased the number again to around 900 to 1000.

Function and meaning

Since the so-called class struggles of the 4th century BC It was also allowed to the plebeians to take office and then to enter the Senate. Until the 3rd century AD, the Senate was always firmly in the hands of the nobility , which included not only the patricians (patres) but also those plebeian families who had made it to the consulate : formed from patricians and ascended rich plebeians a group of very few families who controlled the state for centuries. Although the official form of address for the senators was extended to patres conscripti ("fathers and (new) registered (plebeians)", possibly also "registered fathers") after the class struggles , the strict control over access to the Senate made it difficult for a climber To become a senator, and almost impossible to rise to the consulate as homo novus . The senators were predominantly large landowners , in the late Republic of Latifundia , especially since they had been with them since the lex Claudia de nave senatorum of 218 BC. The exercise of commercial transactions (except the marketing of their own agricultural products) and trade was prohibited in principle.

In view of the long tradition of the Senate, the role of the controlling and guiding body fell to it, although these customary rights were never enshrined in law ( auctoritas senatus ). In the centuries of the republic, the Senate set the guidelines for politics. He shaped foreign policy, as he received foreign envoys and in turn sent out embassies (the people decided on war and peace, however), had a decisive influence on legislation through preliminary advice, initially assigned certain magistrates, was able to remove officials under certain circumstances and administered them beforehand Especially the state finances: early on, many of these decisions and the legislation were delegated to the people's assemblies, but these usually only decided on proposals that the Senate had previously discussed and accepted. Coupled with time-honored tradition, these important tasks made the Senate clearly the heart of the state. For a simple Roman, not respecting the Senate meant not respecting the state. This solidarity was also reflected in the often-invoked formula SPQR , senatus populusque romanus ("Senate and people of Rome"). Since the social, military and political elite of Rome were gathered in the Senate, which, according to the general opinion , had legitimized themselves through services for the res publica , both individual senators and the committee as a whole enjoyed enormous prestige, so that the mass of Roman citizens normally did not oppose the Senate, provided that it appeared unanimously.

Before the beginning of the principate (see below) the senators did not form their own class, but until his entry into the senate a nobilis also formally belonged to the knight class, the equites . Before Augustus, the rank of senator was not hereditary. As a rule, however, the funds for the cursus honorum were only available to members of the nobility or other rich Roman knightly families (such as in the case of Cicero): the election campaign was very expensive, the office unpaid. Nevertheless, it was possible for ambitious men (mostly with the support of wealthy sponsors) to hold the lower senatorial offices and to sit on the back benches of the Senate as former quaestors or tribunes. Even the praetur was sometimes accessible for such men, but they only became consul in exceptional cases (for example Gaius Marius and Cicero ). If they succeeded, it was in fact synonymous with the admission of their family to the nobility.

The senators also had their own hierarchy among themselves, based on their origin (for example, the patricians initially had extended voting rights vis-à-vis the plebeians ), the previously held office and the age: the oldest former consul (or the one who was most frequent Consul, or the oldest existing censor) was therefore in principle the most respected senator, but the respective chairman could set his own accents. In addition, the senator who was the first to enter the list at a Senate meeting and to be the first to vote was called princeps senatus (“first of the Senate”) or caput Senatus (“head of the Senate”). The meeting, however, was always chaired by the official who had convened the Senate. The consuls, the praetors and, after the disputes, the tribunes had the right to do so. It should be noted that even before the final phase of the republic there were phases in which both the hierarchy within the Senate and the dominance of the Senate within the state were massively questioned.

The Senate meetings had to take place in consecrated rooms within the city of Rome or a maximum of a mile outside the Pomerium , for example when promagistrates who were not allowed to enter the city were to speak in the Senate. The most important meeting place was the Hostilia Curia on the edge of the Roman Forum , after its destruction in 52 BC. The Curia Iulia . There was also a Curia on the Capitol and in the complex of the Pompey Theater (known as the site of the murder of Caesar). The Senate could also meet inside a temple; This is known for the temple of Capitoline Iuppiter , Iuppiter Stator , Castor and Pollux and Apollo . Votes were only valid if there were only senators in the room.

The Senate performed its administrative duties under customary law. The few tasks contained in laws consisted, among other things, in the assignment of certain tasks to the various generals during the war or from provinces to the praetors and consuls who had been praetors (although the relevant resolutions could possibly be repealed or replaced by the popular assembly). The senators also had financial sovereignty. In addition, due to its long tradition and the authority connected with it, the Senate was the guardian of custom and order and the keeper of traditions. Overall, the republic was dominated by senatorial power; Despite democratic elements, the Roman Republic was therefore, according to the prevailing research opinion , an aristocracy that was in fact controlled by the nobility.

Since Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (133 BC) the conflicts within the Senate became more and more intense; those senators who, like Gracchus, came into conflict with the majority, now turned more and more often to the popular assembly in order to achieve their goals. These popular politicians therefore sought to weaken the Senate's authority, while their opponents (the Optimates ) sought to maintain the traditional primacy of the body on which they represented the majority. It was the popular politician Caesar who took the decisive step towards disempowering the Senate by prevailing against the majority of the Senate in a civil war and having himself appointed dictator for life.

The Senate in the Empire

After a century of civil wars, most senators had accepted that the era of almost unlimited Senate rule was over. The last attempt to preserve the republic in its old form with the assassination of Caesar ended in a bloody disaster that was fatal for many senators: In another long civil war, the Caesarians first defeated the remaining supporters of the republic and then fought against each other for the Power. When Caesar's adopted son Octavian, after his eventual victory at Actium in 31 BC, BC carried out a reorganization of the Roman state system, only very few senators offered serious resistance. In January 27 BC Octavian received the honorary name Augustus because he had renewed the republic. In truth, however, he established sole rule. In the following system of the principate , which formally allowed the republic to continue to exist, but transferred decisive powers to the princeps , i.e. the “first” of the state, the senate effectively lost its decision-making power. But at the same time the first princeps or emperor tried to raise the prestige of the senators, who only now became a separate, inheritable class ( ordo senatorius ). Augustus therefore passed moral laws, and the number of senators was again reduced to 600 in order to increase exclusivity. The self-designation as princeps therefore deliberately aroused associations with the republican position of princeps senatus .

Under Augustus, the Senate, bled to death and grateful for the end of the civil wars, was able to build a relatively friendly relationship with the new ruler. Augustus himself always endeavored to rule in peaceful coexistence with the Senate, especially since he had to rely on the cooperation of the senators if he wanted to administer the empire. He tried unsuccessfully to preserve the old senatorial families through marriage laws favoring married senators, and especially senators with children. Already at the beginning of the 2nd century there was only one old patrician family under Hadrian with the Cornelii Dolabelae : Servius Cornelius Dolabella Metilianus Pompeius Marcellus was the last surviving suffect consul of old Patrician descent in 113. New gentes , who owed their position solely to the emperors, took the place of the old republican families. From the beginning, the emperor had the right to admit men into the senate who had not previously held a corresponding office ( adlectio ). An adlectio inter consulares , that is, to the highest rank in the Senate, the former consuls, was only possible since the 3rd century.

The rivalry between the individual senators was also considerable in the principate and late antiquity; Now, however, this was no longer expressed in the competition for votes, but in courting for the favor of the emperor, the source of offices and honors. Especially in phases of crisis, for example in connection with succession disputes or usurpations, the Senate regularly did not act as one, but split up into two or more parties.

More and more members of the Senate were Romanized provincials who came first from the west of the empire, later from Greece, Asia Minor and the Orient, and finally from Illyria and North Africa in the 3rd century. At the end of the 2nd century, just under half of the senators were from Italy. The senatorial title was now more and more detached from participating in the Senate meetings, which continued to take place twice a month in Rome. Former magistrates lived as honorary senators on estates all over the empire that were directly subordinate to the governor.

The first conflict between the emperor and the senate arose when Augustus died in 14th. Neither his successor, Tiberius, nor the senate knew how to deal with this completely new situation - should the unique position of the first princeps now be transferred to an heir - and they met each other with keen suspicion. In the first years of his rule, however, Tiberius cooperated quite closely with the Senate. He saw it not only as an advisory body, but also demonstratively as a decisive body, and gave it important rights of the people's assembly early on (in particular the election of consuls and praetors); in doing so he strengthened the organ that had in fact lost much of its importance in Augustus' last years. The principate, however, was so well established that many senators considered its concession to be inappropriate and hypocritical. The few areas in which the Senate was now legally allowed to make decisions were by no means important for major politics. Only the legislation was formally still incumbent on the Senate, although the emperor could de facto legislate even without consent (see rescript ). It was not until later in the 3rd century then stated Herennius Modestinus explicitly that a lex will no longer be made in due time by the people but by the emperors ( Digest 48 tit.14 s1).

Since Tiberius, the Senate has always tried to keep to itself the right of formal appointment as emperor, which was still granted to it. An imperial rule was actually only formally legitimized by a corresponding senate resolution (since at the latest since Vespasian all special powers have been granted by a single lex de imperio ), but there have been enough cases in Roman history in which new emperors did not care about it, but only with them ruled they supportive legions in the back and simply forced the approval of the Senate: to Imperator it was proclaimed by the army, not the senators. The Senate was powerless against this, even if it occasionally tried to represent a counterpoint to the ever-increasing influence of the military. In 41, after the assassination of Caligula , the re-establishment of the republic was discussed (in vain). This dispute probably reached its climax in the year of the sixth emperors in 238, when the Senate arbitrarily appointed two new emperors, Pupienus and Balbinus , after the death of the two Gordians who had rebelled against Maximinus Thrax - a unique process. Only 99 days later, the two quarreling rulers, behind whom different groups in the Senate stood, were murdered by the soldiers of the Praetorian Guard , which illustrated the real balance of power. Some senators articulated the interests of their class (and sometimes their rejection of certain emperors) by writing historical works in which a clearly pro-senatorial position was represented (see Senatorial historiography ).

In principle, the influence of the Senate depended heavily on the respective emperor. While in the first three centuries of the empire many rulers (such as Vespasian or Trajan and Severus Alexander ) tried to demonstrate demonstratively to rule in agreement with the body, the senate became more and more especially from the 3rd century, during the time of the soldier emperors and more marginal. Since the late 260s, the emperors generally refrained from asking the Senate for formal confirmation of their rule - this had become superfluous. This was also due to the fact that Emperor Gallienus had excluded the senators from military service around 260: If the emperors had initially been dependent on the cooperation of the senators in the military and administration for a long time since Augustus, this phase now came to its end, and with it it also declined the importance of the Senate continues to decline. Since the time of the imperial crisis of the 3rd century it was no longer necessary to be a senator in order to become emperor.

The Senate in Late Antiquity

Diocletian gave the Senate Curia the shape it has today. Due to the constant absence of most emperors in late antiquity - since 312 at the latest, only a few emperors stayed in the city for a long time - the Senate was initially able to create greater political freedom for itself. Nevertheless, the decline in Senate importance could not be stopped altogether; the Senate lost the last vestiges of real power around 300. Since many chivalrous offices were now combined with senatorial rank, membership of the ordo senatorius also lost its exclusivity. The emperors no longer required recognition by the Senate, and the right to legislate continued to exist de jure , but was no longer used. During the civil wars after 306, Constantine I had himself elevated to the rank of senior Augustus by the Senate in order to gain prestige over his rivals, but this remained an exception. After that, the only remaining privilege was actually to judge peers if they were accused of high treason. However, the senators continued to enjoy enormous social prestige and saw themselves as the “better part of humanity” ( pars melior generis humani , Symm. Epist. 1,52). And in isolated cases the assembly offered at least a stage for political decisions, for example when the Codex Theodosianus 438 was proclaimed .

Many senators were extremely conservative and based their claim to social priority on Rome's great past; The response to innovations was correspondingly cautious. At least until the suppression of the usurpation of Eugenius in 394, the Senate was therefore a refuge of pagan traditions: Even if more and more Christians belonged to the Senate in the course of the 4th century, such as the extremely influential Sextus Petronius Probus , the pagan senators still provided a considerable opposition group. The best-known representatives of this group at the end of the 4th century were Quintus Aurelius Symmachus , Virius Nicomachus Flavianus and Vettius Agorius Praetextatus (see also the dispute over the Victoria Altar ). After the violent end of Eugenius, the pagan traditionalists soon disappeared into insignificance; In any case, hardly anyone took the public side of the old cults of the gods, which had been banned under Theodosius I.

Even after the so-called division of the empire in 395 , the western senate retained its prestige, but since Constantine there was also a senate in Constantinople that had enjoyed the same privileges as the western Roman since Constantius II . However, the Eastern Roman senators were apparently never as extremely wealthy as their Italian "colleagues". The Senate continued to be seen as the embodiment of the greatness of Rome. Some powerful senatorial families such as the Anicier were present in both halves of the empire and thus formed a connecting link. In east and west the senators divided themselves into the rank classes of clarissimi , spectabiles and illustres ; when their number around 430 had become too large, the clarissimi and spectabiles were deprived of the right to participate in Senate sessions. The Senate thus effectively became an assembly of the highest active and former imperial officials, from then on it had barely more than 100 actual members and again represented the secular imperial elite. Theodosius II and Valentinian III. 446 also decreed that the Senate would henceforth again have to deliberate on every new law, which underscored the renewed importance of the body. In very few cases, senators were even reinstated as military commanders, for example in 528 under Emperor Justinian .

Remarkably, it was not the case that with the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476, the Senate also came to an end. Instead, the western senate continued to exist through the entire 6th century, even if its meaning under the Germanic rule that followed after the end of the empire is unclear. Apparently, however, they cooperated successfully with the new masters overall. Even under Odoacer and Theodoric , the privileges of the senators were confirmed, coins with the legend SC ( senatus consultum ) were minted , and two consuls were appointed annually - one in the east and one in Italy. In the Colosseum , the preferred seats for the senators were renewed again around 500, as preserved inscriptions show. The enormous fortunes of a few senatorial families initially remained, and the last surviving senatus consultum dates from 533.

After 534 - the following year the attack of the Eastern Roman troops on the Ostrogoth Empire began - there is no longer any consul listed for the West. The Senate continued to exist, but the long war between the Goths and Eastern Romans ruined the Senators. When, after his victory in 554, Emperor Justinian abolished almost all of Italy's senatorial offices (only the city prefecture was retained) in order to rule the country directly from Constantinople, the importance of the Western Roman Senate sank rapidly again, and with the incursion of the Lombards in 568 his fate finally sealed. The last clearly attested action consisted in the sending of two embassies to Constantinople : In 578, patricius Pamphronius congratulated the new emperor Tiberius Constantinus on his accession to the throne and brought him 3,000 pounds of gold on behalf of the Senate. But his request for imperial help against the Lombards was ineffective, and a second embassy in 580 was unsuccessful, as Tiberius had to turn his attention to other fronts. When Pope Gregory the Great was raised in 590, the Senate may have played a small role again. It is true that this same Gregory then spoke in a sermon in 593 that there was no longer a Senate ( Senatus deest , or. 18); but he himself mentions the committee one last time when the Roman clergy and senate acclaimed the images of the new Emperor Phocas and Empress Leontia on April 25, 603 in Rome .

Since 542 there was no (non-imperial) consul in Constantinople either, but the Byzantine Senate continued to exist until the end of the Byzantine Empire . However, the Eastern Roman senate aristocracy disappeared after the middle of the 7th century: During the defensive struggles against the Arabs, it was replaced by new rising families who no longer had the old sense of class or the classical education ( paideia ) that were typical of the ancient senators were. The Senate of the middle and late Byzantine era was therefore reminiscent of that of antiquity.

The Gallo-Roman senate nobility was a specialty .

Special Senatorial Powers and Rules of Procedure

The Senate Resolution

The Senate resolution (das senatus consultum , abbreviated to SC ), sometimes referred to as decretum or sententia , was an instruction that the Senate issued to an official after a closed discussion and vote. In theory, such a decision (or literally: “advice”) was not binding, but in the days of the republic hardly anyone dared to oppose such a “advice”, as this was a rebellion against the explicit majority will of the nobility and thus in usually would have meant the end of a career.

After the vote, the Senate's resolution was written down and archived in the Temple of Saturn, where the state treasure also rested. Less important documents, for example minutes, not particularly important speeches and so on, were in the Tabularium , a 78 BC. State archive built in BC. In addition, the senators were obliged to publish their resolutions. Since Caesar the decision lists have been posted in the Roman Forum for the entire public.

At times, constitutional obstacles were placed in the way of a Senate resolution. So it could happen, for example, that a tribune of his veto lodged or that religious concerns or pretexts put forward. In this case, the result of the vote was downgraded from a senatus consultum to a senatus auctoritas , i.e. the will of the Senate, and had to be put to the vote again. In principle, only senators were allowed to be present during a vote.

Since 133 BC In addition, there was a so-called senatus consultum ultimum , i.e. an extraordinary Senate resolution that gave certain officials extraordinary rights for a certain period of time. With this measure, the need to appoint a dictator should occur as rarely as possible. As a rule, this act consisted in giving the two consuls unrestricted power for their one-year term of office in order to fight the alleged enemies (hostes) of the state by all means (legal formula videant consules, ne quid res publica detrimenti capiat - “like the consuls make sure that the community is not harmed ”). The legality of this instrument, with which the Senate openly presented itself as the highest decision-making body in the late republic (while theoretically this should be the various popular assemblies ), was always very controversial. This also applied to the fact that during the time of the civil war the Senate increasingly presumed to independently accept men into its ranks who had not previously been elected to office by the people.

In the middle of the first century, the Senatus Consultum Velleianum was issued , which regulated intercessions by women and remained relevant until modern times . During the imperial era, however, legislative votes that were introduced independently of the emperor became increasingly rare; The latest known case of this kind occurred when, in 178, with the senatus consultum Orfitianum, the right of inheritance in the event of the death of a woman was newly regulated in favor of her children. Regardless of this, the Senate made further decisions in the following centuries: The last attested senatus consultum dates from the year 533.

Case law in the Senate

As a countermeasure to the dwindling power of the Senate under the emperors, from 4 BC Chr. The Senate granted the right to judge in cases of repetundae (trial against a provincial governor for illegal appropriation of funds) and maiestas (high treason) in appropriate committees. With the first case of this kind under Augustus , such a custom developed.

A process de repetundis (i.e. the reclaiming of illegally obtained funds) happened very often, as the greed of the governors of a province could practically not be curbed by any law. The best known is probably the charge against Marcus Priscus , the governor of Africa, described by Pliny in his letters . Pliny and Tacitus sued the governor and unanimously claim that the accused also had to fear criminal consequences.

The procedure corresponded to the usual procedure in court proceedings: two senators were responsible for prosecution and defense. After a three-day process, all four subjects gave their closing speeches. Thereafter, various penalties were put up for debate by the consuls and proconsuls . In the end, the defendant was judged with a vote.

The maiestas charge is less well known. In fact, the term high treason could be interpreted extremely broadly among the Romans; since Augustus, insulting the emperor was also and above all considered an offense against the “majesty” of the state. The Senate ruled on cases that could range from an armed coup to taking a coin (with the imperial portrait on it) to the toilet or selling an imperial statue. Theoretically, almost anyone could be charged with high treason, provided that an accuser was found, which led to the horrors of the high treason trials under Tiberius or Nero , in which hundreds were killed, while it was considered a sign of a "good" emperor not to allow such charges To spare senators or at least let the Senate decide their fate. One should bear in mind that majesty trials were always a means of competition within the senatorships - after all, it was never the rulers who brought charges, but rather senators or Roman knights who, in the event of conviction, could also hope for a large part of the assets of the accused. With the end of the principate , the majesty trials also disappeared, but even in late antiquity, some emperors sometimes granted the senators the right to sit in court over comrades accused of high treason - but this was only a friendly gesture of the ruler. In such cases, the “five-man court” (iudicium quinquevirale) , which consisted of the city prefect and four other senators and, for example, carried out the trial against Boethius , was usually called .

In civil law matters, the Senate already had certain possibilities of jurisdiction in the republic, which could be expanded a little during the imperial era. However, one case is known in the late republic when a high treason trial was carried out before the Senate: When Catiline failed with his attempted coup, he was judged in the Senate. Various high politicians, according to Gaius Iulius Caesar , denounced this as unlawful and were unable to prevent the execution of the Catilinarians, but later caused considerable difficulties for the consul responsible, Cicero.

literature

- Jochen Bleicken : The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Basics and development (= UTB. Vol. 460). 8th edition, unchanged reprint. Schöningh, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 3-8252-0460-X .

- Ursula Hackl : Senate and magistrate in Rome from the middle of the 2nd century BC Until Sulla's dictatorship (= Regensburg historical research. Vol. 9). Lassleben, Kallmünz 1982, ISBN 3-7847-4009-X (At the same time, slightly abbreviated: Regensburg, Universität, habilitation paper, 1979).

- Arnold Hugh Martin Jones : The Later Roman Empire 284-602. A Social, Economic and Administrative Survey. 3 volumes consecutively numbered, Blackwell, Oxford 1964 (ND in 2 volumes, 3rd printing. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore 1992). (Comprehensive presentation of late antiquity, which also deals with the late Roman Senate).

- Christine Radtki: The Senate at Rome in Ostrogothic Italy. In: Jonathan Arnold, Shane Bjornlie, Kristina Sessa (Eds.): A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy. Brill, Leiden 2016, pp. 121-146.

- Ainsworth O'Brien Moore : Senatus . In: RE Suppl. 6 (1935), pp. 660-800.

- Dirk Schlinkert: Ordo senatorius and nobilitas. The constitution of the senate nobility in late antiquity. With an appendix about the praepositus sacri cubiculi, the “almighty” eunuchs at the imperial court (= Hermes. Individual writings. Vol. 72). Steiner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-515-06975-5 (also: Göttingen, Universität, Dissertation, 1995).

- Richard Talbert: The Senate of Imperial Rome . Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton 1985, ISBN 0-691-05400-2 (standard work).

Remarks

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Weeber : Everyday life in ancient Rome. A lexicon . Düsseldorf u. a. 1995, p. 208.

- ↑ See FK Ryan: Rank and Participation in the Republican Senate . Stuttgart 1998.

- ↑ Jochen Bleicken: The constitution of the Roman republic . 3. Edition. Paderborn 1982, p. 110.

- ↑ Although some prominent researchers, above all Fergus Millar , have pleaded in recent years not to overestimate the influence of the Senate and the nobility and to view the Roman Republic as a democracy at its core, this position has not prevailed. See Fergus Millar: The Political Character of the Classical Roman Republic, 200-151 BC In: The Journal of Roman Studies 74, 1984, pp. 1-19.

- ↑ Mason Hammond : Composition of the Senate, AD 68-235. In: The Journal of Roman Studies . Volume 47, number 1–2, 1957, pp. 74–81, here: p. 75.

- ↑ On the change in the Senate aristocracy, which was formally "Christianized", cf. the important study by Salzman: Michele R. Salzman, The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: social and religious change in the western Roman Empire, Cambridge / Mass. 2002.

- ↑ John Malalas 18:26; see. Hartmut Leppin : Justinian. Stuttgart 2011, p. 128.

- ↑ Monumenta Germaniae Historica Epistolae II. Gregorii I papae Registrum epistolarum. Liber XIII, 1 p. 364 f. ; see. TH Neomario: History of the City of Rome . Kiel 1931, p. 675; Jeffrey Richards: The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages, 476-752 . London 1979, p. 246.