Constantine the Great

Flavius Valerius Constantinus (* on February 27 between 270 and 288 in Naissus , Moesia Prima ; † May 22, 337 in Anchyrona, a suburb of Nicomedia ), known as Constantine the Great ( ancient Greek Κωνσταντῖνος ὁ Μέγας ) or Constantine I. , was Roman emperor from 306 to 337 . From 324 he ruled as sole ruler.

Constantine's rise to power took place as part of the dissolution of the Roman tetrarchy ("rule of four"), which Emperor Diocletian had established. In 306 Constantine inherited his father Constantius I after his soldiers had proclaimed him emperor. By 312 Constantine had asserted himself in the west, 324 also in the entire empire. His reign was particularly significant because of the Constantinian change he initiated , with which the rise of Christianity to the most important religion in the Roman Empire began. From 313 the Milan Agreement guaranteed religious freedom throughout the empire, which also allowed Christianity, which had been persecuted a few years earlier. In the following years Constantine privileged Christianity. In 325 he called the First Council of Nicaea to settle internal Christian disputes ( Arian controversy ). Inside, Constantine pushed forward several reforms that shaped the empire during the rest of late antiquity . In terms of foreign policy, he succeeded in securing and stabilizing the borders.

After 324, Constantine moved his residence to the east of the empire, to the city of Constantinople named after him (" City of Constantine"). Many details of his politics are still controversial to this day, especially questions concerning his relationship to Christianity.

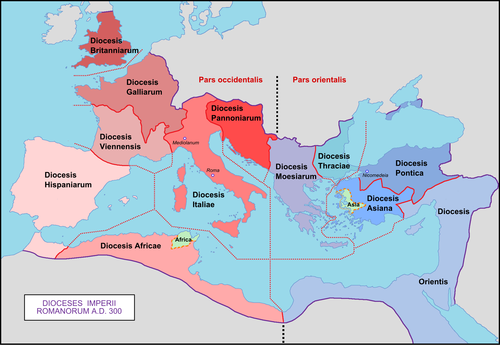

The Roman Empire in the time of Constantine

In the 3rd century the Roman Empire entered a time of crisis ( 3rd century imperial crisis ) in which internal political instability and pressure on the borders increased. Various Germanic tribes and large new gentile associations such as the Franks , Alamanni and Goths caused unrest on the Rhine and Danube . Groups of “barbarians” penetrated Roman territory several times and plundered Roman cities that had previously been largely spared from attacks for almost two centuries. In the east, which was 224/226 Sasanian worlds emerged, which became the most dangerous rival of Rome (see Roman-Persian Wars ). Inside the empire, numerous usurpers and usurpation attempts relied primarily on the large army units that now legitimized the imperial power ( soldier emperors ), so that endless civil wars shook the empire. Even though not all areas of life and provinces were hard hit by the crisis and it was by no means uninterrupted, it turned out to be a severe stress test for the empire.

Emperors like Aurelian therefore introduced reforms in the 270s, but it was only Diocletian , who came to power in 284, who succeeded in putting the empire on a new foundation. He carried out far-reaching reforms and fundamentally reshaped the empire. Among other things, Diocletian introduced a new tax system ( Capitatio-Iugatio ) and rearranged the army by dividing it into Comitatenses as a mobile field army and Limitanei as border troops. The crisis was finally overcome, the empire entered late antiquity . As a reaction to the simultaneous military burdens on the various borders and the constant usurpations of ambitious generals, a multiple empire was introduced, the tetrarchy , in which Diocletian acted as senior Augustus with three co-emperors subordinate to him. This system was based on the appointment of successors instead of dynastic succession and primarily served to prevent usurpations. In Diocletian's last years of reign there was persecution of Christians . In 305 Diocletian resigned voluntarily and forced his co-emperor Maximian to follow this example, so that the previous sub -emperors Constantius I (as a replacement for Maximian in the west) and Galerius (as a replacement for Diocletian in the east) followed as senior emperor ( Augusti ) . Nevertheless, contrary to Diocletian's intention, the dynastic principle soon prevailed again (see dissolution of the Roman tetrarchy ). Years of bloody civil war broke out, at the end of which Constantine was sole ruler of the empire.

Life

Adolescence and elevation to emperor (until 306)

Constantine was born on February 27 of an unknown year in the city of Naissus (now Niš in Serbia ). His age at the time of his death (337) is given very differently in the sources. Therefore, in research, the approaches for the year of birth vary between 270 and 288, with an early dating being considered more plausible. His parents were Constantius and Helena . According to the sources, Helena is said to have been of very low origin. According to Ambrose of Milan , she was a stable maid ( stabularia ). This has meanwhile been partly interpreted to the effect that her father was an official of the Cursus publicus (stable master); accordingly she would have been of high birth. In any case, in later years she became a Christian, allegedly under the influence of her son. It is documented at the court of Constantine, went on pilgrimages and played an important role in the later Christian legend about the " True Cross of Christ ".

Like many Roman soldiers, Constantius came from the Illyricum and grew up in a simple family. He was inclined to henotheism and presumably worshiped the sun god Sol . Constantius was probably an officer under the emperors Aurelian and Probus , but only achieved political importance under Diocletian. The fact that he descended from Emperor Claudius Gothicus , as was later claimed, is mostly considered an invention. He was evidently a capable military man and won a victory over the Franks around 288/89. How long the relationship between Constantius and Helena lasted is unclear. A legitimate marriage, although implied in some sources, has been questioned; however, this question is controversial in research. A possibly illegitimate origin would have been problematic for reasons of legitimacy, but Constantius evidently confessed to his son and took care of his upbringing. Constantine had six half-siblings from his father's marriage to Theodora , a stepdaughter of Emperor Maximian's no later than 289 : the brothers Julius Constantius , Flavius Dalmatius and Flavius Hannibalianus and the sisters Constantia , Eutropia and Anastasia .

Otherwise hardly anything is known about Constantine's childhood and youth, especially since the legends about Constantine began early on. After Constantius had become the western Caesar (lower emperor) under Maximian in Diocletian's tetrarchy in 293 , Constantine first lived in the east at the court of the senior emperor Diocletian. There he received a formal, including literary training, so that he could be considered a well-educated man. Presumably he also came into contact with the educated Christian Lactantius , who was active at Diocletian's court. Lactantius then stepped down at the beginning of the Diocletian persecution of Christians in 303, which marked the end of a religious peace that had existed for 40 years. It is not known whether Constantine was involved in this persecution; but there is nothing to be said for it. He made a career in the military, probably held the post of a military tribune and distinguished himself in battles against the Sarmatians on the Danube under Galerius .

In 305 his father Constantius rose to Augustus (Upper Emperor) of the West after Diocletian and Maximian had resigned from their office. In the same year Galerius, now also Augustus of the East, sent Constantine back to Constantius in Gaul. According to the Origo Constantini , a historical work from the 4th century that contains reliable information, Constantine was held hostage at court. Other sources report similar things, such as Aurelius Victor , Philostorgios and the Byzantine historian Johannes Zonaras . Constantine's biographer Praxagoras from Athens, on the other hand, explains this stay with an education there. However, it is entirely plausible that Diocletian, who did not want a dynastic succession, and later Galerius put Constantine under supervision. Whether Galerius then, as several sources report, deliberately put Constantine's life in danger before he reached his father after a dramatic journey is doubtful because of the tendentious nature of these reports. The fact that Galerius let Constantine go away may be due to a previous agreement with Constantius to include his son as Caesar in the tetrarchy, but the exact background is unknown. It is controversial in research whether Constantine was a usurper .

Constantine found his father in Bononia and accompanied him to Britain , where the Picts and Scots had invaded the Roman province. Constantius led a successful campaign against the invaders and threw them back. When he died unexpectedly on July 25, 306 in the camp of Eboracum (today York ), Constantine was immediately proclaimed emperor by the soldiers present. The background is unknown, but it is very likely that Constantius systematically built up his son as his successor. The soldiers evidently preferred dynastic succession within a familiar sex to the tetrarchical concept; Constantine himself also emphasized this element of his legitimation very much in the following years and thus turned away from the ideology of the tetrarchy. But his possibly already proven military skills spoke for him. Allegedly, the emperor's uprising came about through the influence of an Alemannic prince named Crocus .

The End of the Tetrarchy (306-312)

With the rise of Constantine as emperor in 306, which basically represented a usurpation , the laboriously established tetrarchic order of Diocletian was broken. Despite some tentative restoration efforts, it could not be restored (see dissolution of the Roman tetrarchy ). The dynastic idea, to which the majority of the soldiers adhered, was now gaining ground again. The situation remained tense for Constantine, since his empire was de facto illegitimate, but he could trust that the Gallic army was loyal to him and that his rule was not directly threatened. Gaul and Britain were firmly in his hand. Galerius, after the death of Constantius the most senior emperor, refused Constantine recognition as Augustus , but he lacked the means to take action against the usurper, especially since Constantine's usurpation was not the only one. At the end of October 306, Maximian's son Maxentius had been elevated to emperor by the Praetorian Guard and urban Roman circles in Rome and now claimed Italy and Africa . Finally, Galerius appointed Severus as the new Augustus of the West and Constantine as his Caesar , with which Constantine was content for the time being.

Maximian, who had resigned reluctantly in 305, may have favored the uprising of his inexperienced son Maxentius. He also reappeared as emperor in 307 and cooperated with Maxentius. They were able to fend off the attack of Severus, who, as the new regular Augustus of the West, was supposed to put down the usurpation on behalf of Galerius. Severus was eventually caught and later executed. In the same year Maximian visited Konstantin in Gaul and made an agreement with him: Konstantin separated from Minervina , the mother of his son Crispus (305–326), and instead married Maximian's daughter Fausta . With Fausta, who died in 326, Constantine had three sons, Constantine II , Constantius II and Constans , who later succeeded him as emperor, as well as the two daughters Constantina and Helena . With the new marriage, Constantine sealed an alliance with Maximian. Without being entitled to do so, Maximian even appointed Constantine to Augustus , which underscored the involvement of Constantine in Maximian's tetrarchical "Herculean dynasty", from which Constantine probably hoped for additional legitimacy. With this, however, the agreement with Galerius was no longer valid.

Afterwards, however, Maximian fell out with Maxentius. Presumably the former emperor claimed full power for himself; in any case, Maxentius apparently played no part in the agreement with Constantine. However, Maxentius had in the meantime fended off an attack by Galerius and therefore confidently rejected his father's request for resignation. At the so-called Imperial Conference of Carnuntum in 308, at which Diocletian made another political appearance, Maximian was forced to resign. Constantine's title of Augustus was withdrawn from Constantine, but as Caesar he rejoined the tetrarchical order and, unlike Maxentius, was not a usurper. Constantine's co-emperor in the third tetrarchy was next to the eastern emperors Galerius (293 / 305-311) and Maximinus Daia (305 / 310-313) nor Licinius (308-324), who was planned as the new Augustus in the west. Maximinus Daia, however, did not accept the fact that Licinius, who had never held the dignity of Caesar, was now above him in rank. Constantine was also unwilling to step back into the second row, while Licinius did not have the means to enforce his supremacy in the west and defeat Maxentius. Galerius tried to mediate and appointed both Constantine and Maximinus Daia "sons of Augusti", but shortly afterwards he was forced to recognize the Augustus dignity of both of them. Thus the Imperial Conference had no stabilizing effect either and only postponed the later conflict.

Little is known about the domestic political measures of Constantine in his part of the empire (Britain and Gaul, which came before 312 Hispania). The Christians, whom his father had not been hostile to (the Diocletian persecution of Christians was much less pronounced in Western Europe than in the rest of the kingdom), Constantine again allowed worship. Galerius, on the other hand, had the Christians persecuted in the eastern part of the empire until 311. It was only when the hoped-for suppression of Christianity did not materialize that he ended the persecution with his edict of tolerance . At that time, Constantine resided primarily in Augusta Treverorum , today's Trier , which he had magnificently expanded. Numerous new building complexes were built, including representative buildings such as the Constantine Basilica and the Imperial Baths . As the later seat of the Gallic prefecture, Trier was also the administrative center of the western provinces (except Italy and Africa). In addition, Constantine initiated construction programs in other Gallic cities and took care of border security, especially on the Rhine. Militarily he was very successful and secured the Rhine border again. At times he was very brutal; so the captured Franconian kings Ascaricus and Merogaisus were thrown alive wild animals to celebrate a victory in the arena. In 309, Constantine in Trier had the solidus minted as a new “solid” denomination instead of the aureus , which in the 3rd century had lost massive amounts of fineness and thus value . As such, it remained in circulation until the conquest of Constantinople (1453) .

Maximian, meanwhile deprived of all means of power, went to his son-in-law Constantine in 308, who welcomed him in Gaul, but did not allow him to play a political role. However, Maximian was not satisfied with a life as a private citizen. In 310 he intrigued against Constantine, who was bound on the Rhine front by the defense against Germanic attackers. The plot failed and Maximian sought refuge in Massillia . He was eventually delivered by his troops and committed shortly after suicide . After that, Constantine officially and definitively accepted the title of August. In addition, he distanced himself from the factually broken tetrarchical order and the legitimation by the Maximian dynasty associated with Hercules. During this period, Constantine clearly favored the sun god Sol on coins. He now constructed a descent from Claudius Gothicus , a soldier emperor of the 3rd century, who was described very positively in senatorial historiography . With this, Constantine created a new legitimation and officially postulated his own dynasty .

The situation remained tense even after the death of Galerius in 311. There were still four emperors, in the west Constantine and Maxentius, in the east Licinius and Maximinus Daia, who fought over the legacy of Galerius there. Maxentius is mostly portrayed very negatively in the sources. He had military successes, including the suppression of an uprising in Africa (usurpation of Domitius Alexander ). He was also quite popular in Rome and his religious policy was tolerant. Maxentius and Maximinus Daia entered into negotiations. This threatened Licinius in the east. He therefore sought a rapprochement with Constantine, who was already preparing a campaign to Italy. In 311 or 312 Licinius became engaged to Constantia , a half-sister of Constantine. Between Maxentius and Constantine, on the other hand, an open rift finally occurred when Constantine was accused of murdering Maximian.

Divine omens? The victory over Maxentius in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312

In the spring of 312 Constantine marched into Italy after he had already attached Hispania to his domain. Maxentius was well prepared for this, however, as he had several cities in northern Italy fortified. His troops were numerically superior; According to a panegyric who is not known by name , he had 100,000 men, some of whom had gathered in northern Italy in the area of Turin , Verona and Segusio . According to this source, Constantine, on the other hand, was only able to carry a quarter of his entire army, i.e. around 40,000 men, because of the endangerment of the Rhine border. His army of British, Gallic and Germanic troops was much more battle-tested than the Italian. Konstantin advanced quickly and apparently surprised the enemy. He was victorious at Turin, Brescia and finally at the Battle of Verona , where the Praetorian prefect of Maxentius, Ruricius Pompeianus , fell. Several cities opened the gates to Constantine without a fight, including the important royal seat of Milan .

Now Maxentius made a difficult to understand decision that even contemporaries could not explain. Instead of waiting in the fortified city of Rome, which Constantine could not have stormed, he sought the field battle. His motive is unclear. Lactantius reports of unrest in Rome and a favorable prophecy that encouraged Maxentius to attack. These may be topical motives. Perhaps Maxentius thought that after Constantine's initial successes he had to make a name for himself as a general. In any case, on October 28, 312 he went to meet Constantine. North of Rome, at the Milvian Bridge , the decisive battle broke out . The bridge had previously been torn down and an auxiliary bridge was built next to it. A few kilometers to the north there was vanguard skirmishes in which Maxentius's troops were defeated, whereupon they fled to the auxiliary bridge. This escape seems to have finally turned into open panic, because there was probably no battle in the real sense on the Tiber itself. Rather, the soldiers of Maxentius pushed south, many drowned in the river. This is what happened to Maxentius, whose army thus disbanded.

Perhaps Maxentius had wanted to lure Constantine into a trap; At least this is suggested by the Praxagoras report, which speaks of an ambush by Maxentius, to which he himself fell victim. Maxentius could have planned to let Constantine's troops break through, in order to then encircle them between the city of Rome, the Tiber and the formations north of Rome; but he may have failed with this plan when his troops fled in disorder.

The sources speak of a divine sign that Constantine is said to have been given before the battle. Lactantius' report is written very promptly, while Eusebios of Kaisareia wrote his account, which is probably based on statements by Constantine to the bishops, only several years later. Lactantius reports a dream apparition in which Constantine was instructed to have the heavenly sign of God painted on the shields of the soldiers; then he had the Christ monogram affixed there. Eusebios tells of a heavenly phenomenon in the form of a cross with the words “ Through this victory! “And shortly afterwards mentions the Christ monogram. A " pagan variant" of the legend is offered by the Panegyricus of Nazarius from the year 321, while the anonymous panegyric from 313 attributes the victory to the assistance of an unnamed deity.

These reports have been discussed intensively in research for a long time. Tales of divine apparitions are not uncommon in antiquity, especially since all Roman emperors took divine assistance for themselves. The legendary reports about Constantine's vision are to be seen as part of his propaganda self-portrayal. In research, however, a real core is not excluded, for example a natural phenomenon such as a halo , in which sunlight is refracted under certain atmospheric conditions and thus circular and cross structures become visible. In this sense, the "miracle of Grand" in Gaul from the year 310, which Constantine saw, could be classified in another source: a heavenly phenomenon that an anonymous panegyricist interpreted as a divine sign (here with reference to Apollo ) probably happened in coordination with the imperial court.

From a historical point of view, what matters less is what Constantine might actually see than what he believed or claimed to have seen. Under Christian influence he may have believed that the God of Christians was at his side and that he was fulfilling a divine destiny. Therefore, the story of Eusebios represents a message of great value, because it probably reflects the official view of the court, albeit from a later time, when Constantine attached importance to stylization in the Christian sense. However, the labarum mentioned by Eusebios elsewhere is only clearly documented for 327/28, although it may have already existed in a different form. As a Christian symbol, the sign of the cross is already documented several times before 312; for example, Cyprian of Carthage points this out in the 3rd century . The veneration of the cross did not begin until the Constantinian period. The cross first appeared on coins in the 330s.

Elisabeth Herrmann-Otto assumes that the sun vision of 310 was decisive for Constantine. Accordingly, in his imagination, Sol and Christian God were initially united, before he definitely traced the appearance in Grand back to Christian God and "solar elements" receded. According to Klaus Martin Girardet , Constantine also first associated the apparition in 310 with Sol, who was very present on his coins for a few years. Shortly afterwards (311) the emperor related the apparition to the God of the Christians, especially since Jesus was often considered the “sun of righteousness” in late antiquity and a reorientation was not difficult. Since all of this happened well before the battle of the Milvian Bridge, there was no vision in the run-up to it. In his current biography of Constantine, Klaus Rosen argues that the emperor attributed his victory to the assistance of a supreme deity, but this should not be equated with a Christian conversion experience.

What is certain is that Constantine ultimately attributed his victory at Milvian Bridge 312 to the assistance of the Christian God and now ruled unreservedly in the west. After the victory he made a solemn entry into Rome, where the severed head of Maxentius was presented to the population. The Senate of the city came Konstantin with respect contrary; It has long been controversial whether the emperor then made a sacrifice for Jupiter. The Senate recognized the victor as the highest-ranking Augustus , while Maxentius was now stylized as a tyrant and usurper and finally even portrayed ahistorically as a persecutor of Christians by Constantinian propaganda. The Praetorian Guard, the military backbone of Maxentius, was disbanded. As a symbol of his victory, Constantine had a larger than life statue made of himself. In 315 the Arch of Constantine was also inaugurated.

Constantine and Licinius: The Struggle for Autonomy (313-324)

After Constantine had achieved sole rule in the west, he met Licinius in Milan at the beginning of 313, who was now married to Constantia. The two emperors passed the so-called Milan Agreement there . This is often referred to as the Edict of Tolerance of Milan , but this is incorrect because the agreement was not promulgated in a nationwide edict. In the agreement, Christians, like all other religions throughout the empire, were guaranteed freedom of worship. It was not a question of privileging Christianity, but only of equality with other religions. For the Christians it was also important that the two emperors recognized the church as a corporation, i.e. as an institution under public law with all rights and privileges. For the rigorous persecutor of Christians, Maximinus Daia, who had effectively revoked Galerius' Edict of Tolerance, the agreement was a threat, especially since most of the Christians lived in his eastern part of the empire. Only by necessity did he swerve to the new line, but at the same time he was preparing for war against Licinius. At the end of April 313 he was defeated by Licinius in Thrace and died only a few months later on the run. The Eastern Christians welcomed Licinius as a liberator. In fact, he initially pursued a tolerant religious policy. The educated Christian Lactantius , who was employed by Constantine to educate his son Crispus in Trier, viewed Licinius, like Constantine, as a God-sent savior of Christians. It was only because of the later developments that Licinius was portrayed negatively in Christian sources.

Now there were only two emperors left in the empire, but tensions soon arose between them. Apparently Licinius disliked the fact that Constantine passed him over on important decisions such as the occupation of Italy, the marriage agreement, and the Milan Agreement. Above all, Constantine was considered to be the real protector of the Christians in the east, which Licinius could see threatened. Constantine apparently took on this role consciously, because in 313 commemorative coins were made that depict him with the Christ monogram on the helmet, and he intervened in internal church matters such as the Donatist dispute that broke out in 312/13 .

The compromise to return to a tetrarchic order, whereby the Senator Bassianus , who was related by marriage to Constantine , should rule Italy, failed. In 316 it came to an open conflict. The background was a conspiracy against Constantine, which was probably instigated by an officer of Licinius named Senecio , a brother of Bassianus, who was actively involved in it himself. After the plot was discovered, Licinius refused to extradite Senecio. He thus exposed himself to the suspicion of being involved in the conspiracy or of having approved it. The Origo Constantini According to the denial of extradition and allegedly ordered by Licinius destruction of images and statues of Constantine presented in the city of Emona the reason for war. In any event, both sides were ready, the question of power to decide militarily. Constantine marched into the Illyricum with his Gaulish-Germanic troops, about 20,000 men, and advanced rapidly. Licinius opposed him at Cibalae (today Vinkovci ) with 35,000 men and was defeated. He had to flee in a hurry to Thrace , where more troops were standing, but the battle there (near Adrianople ) ended in a draw. In the end, Constantine and Licinius came to an agreement for the time being; Licinius had to evacuate the entire Balkan peninsula . Two sons of Constantine and the only legitimate son of Licinius were made Caesars on March 1, 317.

The tensions between Constantine and Licinius persisted after 316. Since 318 Constantine, who left the border protection on the Rhine to his son Crispus and his officers, stayed mainly in the newly won territories in the Balkans. From 321, both halves of the empire no longer dated uniformly to the same consuls and were preparing for war more and more obviously. In 322, Constantine resided in Thessaloniki , that is, right on the border of the two spheres of power, which Licinius had to take as an open provocation. Licinius also took hostile measures against the Christians, whom he evidently mistrusted in view of Constantine's religious policy. There are said to have been assembly bans, confiscations and forced sacrifices, and Christian sources also speak of planned persecution. Licinius was stylized as a tyrant who was heavily accused (desecration, increasing tax pressure, unjustified incarceration, etc.). Such allegations are problematic in that the topical nature is quite obvious. Ultimately, the details of the actions Licinius took are unknown. Due to the political situation, however, it is quite possible that he tried to restrict Christianity in his domain. In this context, Constantine was able to stylize himself as the savior of Christians in the East and thus also use his Christian-friendly policy for power politics.

When Constantine and his elite groups invaded Licinius' Balkan Province to protect the threatened population from attacks by the Goths , Licinius protested loudly. An ultimately fruitless exchange of diplomatic notes followed, and 324 a decisive conflict ensued. Both sides were armed and led strong armies, each with well over 100,000 men. Constantine probably intended to carry out a combined land and sea operation, but Licinius had holed up with his troops in Adrianople in Thrace, from where they could endanger Constantine's supply lines. But Constantine succeeded in defeating Licinius in the early summer of 324 near Adrianople in Thrace . After the defeat, Licinius fled to the heavily fortified Byzantion . But after Constantine's eldest son Crispus had destroyed the enemy fleet in the sea battle at Kallipolis , he threatened to be cut off and fled to Asia Minor. In September 324 he was finally defeated in the battle of Chrysopolis . He had to surrender, with Constantine promising to spare his life. Licinius, who, like Constantine, had acted quite ruthlessly against his opponents (so he had the families of Galerius, Maximinus Daia and Severus murdered), was nevertheless executed in 325 on Constantine's orders and probably out of power-political calculations, soon afterwards his son too Licinianus Licinius . Constantine was now the undisputed sole ruler of the Roman Empire, which (but only for the time being) meant an end to the bloody civil wars.

Imperial politics as sole ruler (324–337)

The founding of Constantinople

After defeating Licinius, Constantine moved the main residence to the east. This step was not a new one, because the emperors had already chosen different residential cities in the time of the tetrarchy. Constantine is said to have initially considered several locations, but then decided on the old Greek colony of Byzantium . The city was very conveniently located in a strategically important region and was surrounded on three sides by water; Constantine had already recognized the advantages of this situation during the campaign against Licinius. Shortly afterwards he had the city expanded considerably and expanded magnificently.

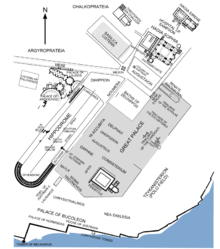

The new royal seat was called Constantinople ("City of Constantine"). By naming it after his name, Constantine followed a tradition of Hellenistic kings and former Roman emperors. The fortifications of the expanded area, which was now more than six times the size of the old city, were improved. A large number of new buildings were also built. This included administration buildings, palace complexes, baths and representative public facilities such as a hippodrome and the Augusteion . The latter was a large rectangular square that housed a senate building as well as the entrance to the palace district. From there a street led to the round Konstantinsforum, where the statue of the emperor was placed on a pillar and a second senate building stood. Numerous works of art from the Greek area were brought into the city, including the famous snake column from Delphi . Constantine had the city inaugurated on May 11, 330, but the extensive construction work was far from over.

The great advantage of the new residence was that it was located in the economically important east of the empire. Churches were built in the now enlarged city, but there were also some temples and many pagan architectural elements that gave the city a classic look. As the extent of the elaborate planning shows, it was intended as a counterpart to "ancient Rome", although the emperor had construction work carried out there too. Constantine had celebrated his Decennalia in Rome in 315 , and in 326 he had the Vicennalia (his 20th anniversary of the reign) celebrated there, which he had previously celebrated in Nicomedia in the east.

For decades Rome had only been the pro forma capital and lost its importance with the new seat of government, even if it continued to be an important symbol for the Rome idea . Constantinople was put on an equal footing with Rome in many respects, for example it was given its own senate, which was subordinate to the Roman one, and was not subject to the provincial administration, but to its own proconsul . In addition, Constantine provided incentives to settle in his new residence. Court rhetoric and church politics even elevated the city to the status of a new Rome. Constantinople, the urban area of which was later expanded to the west, developed into one of the largest and most magnificent cities of the empire and in the 5th century even the capital of Eastern Europe.

The Relatives Murders of 326

In 326 Constantine ordered the murder of his eldest son Crispus and shortly after that of his wife Fausta . The court deliberately suppressed this dark chapter in the biography of Constantine. Eusebios does not mention the events at all, other sources only speculate about it.

Aurelius Victor , who wrote around 360 , only briefly reports on the murder of Crispus, which Constantine ordered for an unknown reason. In the Epitome de Caesaribus , the death of Crispus is linked with Faustas for the first time: because his mother, Helena Crispus, whom she held in high esteem, mourned, the emperor also had his wife executed. Based on this core narrative, later authors adorned the story. In the early 5th century, the Arian church historian Philostorgios presented details of a scandalous story: Fausta is said to have sexually desired Crispus and, when he rejected her advances, induced her husband to kill her stepson out of revenge. When Fausta was unfaithful on another occasion, the emperor had her killed too. According to the pagan historian Zosimos , Crispus was accused of having a relationship with Fausta. Thereupon Konstantin had his son murdered and, when his mother Helena was dismayed about this, also got rid of Fausta by suffocating her in the bathroom. Since the emperor could not wash himself off from these deeds, he became a Christian because he assumed that in Christianity all sins could be redeemed. Zosimos, who wrote around 500 (or his model Eunapios of Sardis ), apparently had no more precise information about the events; so Crispus was not, as Zosimos reports, murdered in Rome, but very probably in Pula . Zosimos used the opportunity to portray the emperor and his preference for Christianity in an unfavorable light. He agrees with Philostorgios about the circumstances of Fausta's death, which is arguably the real essence of both reports.

The confused and partly recognizable tendentious reports of the sources do not allow a reliable reconstruction of the events that modern hypothetical attempts at explanation vary. The scandal stories have topical features and their credibility is very questionable, because Crispus resided mainly in Trier until 326 and therefore had little contact with Fausta. The late antique reporters or their sources can hardly have had access to reliable information about what was going on in the palace.

Political backgrounds are more plausible than personal. Helena and Fausta had held the Augusta title since 324 . After gaining sole rule, Constantine was able to turn to securing his dynasty. Crispus recommended himself through several military successes. As a possible future ruler, he may have been the victim of an intrigue between rival forces for Fausta; the discovery of the intrigue would then have led to action against Fausta. It is also conceivable that Crispus was ambitious and dissatisfied with his position and therefore got involved in a power struggle, which he lost because Constantine favored his legitimate children for the succession. According to the rules of tetrarchy that Diocletian had once introduced, an emperor should actually have resigned after twenty years; It is conceivable that Crispus and his supporters therefore demanded that Constantine should enable Caesar to rise to Augustus in 327 at the latest . But then the murder of Fausta remains unexplained, which in this case probably belongs in a different context. In any case, it was a matter of dramatic, probably political, conflicts at court, which were then covered up.

Domestic politics

Reorganization of the administration

Constantine generally adhered to Diocletian's domestic policy. He drove forward numerous reforms that laid the foundations of the late Roman state. Military and civil offices were strictly separated. The emperor set up a privy council (consistorium) and several new civil offices. These included the office of magister officiorum , head of the court administration and the chancellery (probably shortly after 312 both in Constantine's domain and in the east under Licinius) and that of quaestor sacri palatii , who was responsible for legal issues. The magister officiorum was also responsible for the bodyguard and the agents in rebus , who acted as imperial agents in the provinces and supervised the administration. The office of comes sacrarum largitionum was created for the income and expenditure of the state . The praetorian prefects , who had been purely civil since 312, were of great importance . During the time of the Constantinian dynasty, they acted as close civil advisers to the emperors. Initially, however, they had more thematically and regionally limited official powers. Only after the death of Constantine did they develop into heads of the territorially delimited civil administrative districts of the empire with a corresponding administrative apparatus, which, however, was very modestly equipped by modern standards. Diocletian had already reduced provinces and combined several provinces into dioceses, administered by a vicar. Constantine also set up comites in some dioceses , the precise responsibilities of which are unclear. Overall, the administration was centralized, but it would be an exaggeration to speak of a “late antique coercive state” as in older research.

Representation of power

As under Diocletian, the empire was given sacred legitimacy, which was reflected in the imperial titulature and in the court ceremonies. In addition to the traditional, the foundation for this was increasingly also Christian ideas, so that finally the idea of a secular governor of God arose and the empire was increasingly Christianized. The idea of the “most Christian emperor” (Imperator Christianissimus) was part of the model of rulers at the latest under the sons of Constantine. Explicitly Christian symbols of rule, which were later emphasized, appeared occasionally under Constantine. Characteristic of his reign is a general reference to a supreme deity and a growing distance from pagan symbolism, without the followers of traditional cults being unnecessarily provoked. The pagan nickname Invictus was replaced by the more innocuous Victor . The reference to the pagan sun cult remained under Constantine for some time (see below). So Constantine presented himself on coins and on the lost statue of the Constantine column as a representative of the sun god, although the sol coins became increasingly rare and were finally discontinued. The ideology of the rulers comprehensible in Eusebios von Kaisareia largely reflected the public self-portrayal desired by the court, but interpreted it in an incorrectly unambiguously Christian way. Some traditional pagan ideas of rulership have been transformed into Christianity. The Christian emperor was propagated as the Constantinian ideal of rulers. The dynastic model of rule has been emphasized since 310 (invention of the relationship with Claudius Gothicus ) at the latest . It finally became binding in 317 after the first war against Licinius and the appointment of Crispus and Constantine II as Caesars under Constantine. The court was growing more and more splendid, with Hellenistic-oriental influences making themselves felt. Constantine wore precious robes and a magnificent diadem and sat on a throne chair. The representation of power also included numerous building projects throughout the empire, especially in Rome, Constantinople and the administrative headquarters.

Building policy

One of the central tasks of a Roman emperor was building policy, especially in the public sector. Constantine used the associated opportunities to represent power. An early example is the Constantine Basilica in Trier . The reception hall is one of the few remaining Roman palace buildings and is the largest surviving structure from Constantinian times north of the Alps. He also began building the cathedral in Trier . The remains of a wall painting were found during excavations in the cathedral; they can be seen today in the “Museum am Dom”. Constantine also began building the Imperial Baths , which, however, were never completed in their planned size. The emperor also initiated new building projects in several cities in southern Gaul and, after 312, in Italy, especially in Rome, where a thermal bath was built, among other things. Especially after gaining sole power, Constantine pushed ahead with numerous building projects, the most extensive of which was the new main residence, Constantinople . The emperor gave massive support to Christian building projects, which was not without effect on the population, among other things. the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem and the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem . This patronage extended to several cities in Italy, but also in other parts of the empire such as Gaul, North Africa and Palestine. In Rome, a monumental basilica was built on the area of today's Lateran near the imperial palace complex and the predecessor building of St. Peter's Basilica .

Social and Economic Policy

Constantine had very good relations with the Senate. He ended the marginalization of this body and gave the senators access to higher offices again, albeit only in civil administration. Constantine set up a second senate in Constantinople. The senatorial rank was expanded considerably and soon comprised a large part of the upper class, which is why different classes of rank were established ( viri clarissimi , spectabiles and illustres , of which the latter was the highest). Some senators moved their headquarters to the provinces, where a provincial senate aristocracy was later formed (see Gallo-Roman senate nobility ). The lower ranks of the knights (equites), however, increasingly lost their importance. A general problem was the high financial burden on the urban elites who held voluntary administrative positions ( curials ). Some curials tried to evade this, for example through an ecclesiastical career, which now also promised a lot of prestige. Constantine counteracted this "curial flight" through his legislation.

The connection of the peasants to the soil ( colonate ) has been promoted since Diocletian. The colonies were still free, but with limited freedom of movement. However, overall social mobility was very high in late antiquity; in research it is even considered to be the highest in all of Roman history. According to recent research, neither social solidification nor economic decline can be ascertained; rather, productivity seems to have increased in the fourth century. The main focus of the economy was still largely agricultural, but several provinces benefited significantly from trade. The late Roman trade relations reached in the east to Persia, in the South Arabian area and as far as India (see India trade ), in the north to the Germania magna . Some cities prospered and benefited from the imperial building policy. Constantine's coin reform proved to be effective against inflation, which Diocletian had not mastered, since a new stable currency was now available in the form of the solidus . In this way the danger of an increasing natural economy could be countered. In taxation, Constantine retained the combined land and poll tax ( Capitatio-Iugatio ) introduced by Diocletian , but extended the assessment cycle from five to fifteen years. The share of slave labor declined, which can be seen from the clearly rising slave prices.

legislation

Constantine passed an unusually large number of laws - which were only fragmentarily preserved in the later legal codifications - which was not only positive. Constantine took a mixed position on late classical lawyers. On the one hand, he collected all notae (written legal criticisms ) from Paulus and Ulpian in 321 , insofar as they were related to the Papinians' collections of expert opinions ( responsae ) . On the other hand , seven years later , he decreed a scripture that had been placed under Paul as genuine. Recent research emphasizes that the emperor did not interact directly with lawyers. The delegation was problematic and also encouraged irregularities. There were numerous tightening of penalties: the use of the death penalty was expanded (also in the form of killing by wild animals), other punishments, some of which were very brutal, were added, including the chopping off of limbs for corruption or the reintroduction of the old punishment of " bagging " for killing kinsmen . Crucifixions also occurred occasionally. Other penalties (such as branding) have been lessened. There is little evidence of Christian influence in criminal law. Christian demands, however, corresponded to the prohibition of free divorce issued in 331, the strengthening of widows and orphans and the additional powers for bishops. In addition, the penalty for childless and unmarried people, which had been in force since Augustus, was lifted, which was beneficial to the often celibate clergy. Relationships between free women and slaves were outlawed. A significant part of the innovations concerned family and inheritance law, with ethical and financial aspects playing a role in particular. The increasing penetration of rhetoric into the legal texts impaired their clarity. The monarchical principle was emphasized.

Constitutions from the late reign of Constantine are housed in the Constitutiones Sirmondianae . Manuscripts of Constantine can be found in the Fragmenta Vaticana on regulations of emancipation and on changes to the sales law .

Military and foreign policy

The army reform already promoted by Diocletian was largely completed under Constantine. There was now a movement army ( Comitatenses ) and a border army ( Limitanei ) , with the emperor significantly increasing the proportion of mobile units. Some pagan historians criticize this step, but it made it possible to stabilize the border regions in the long term, as enemies could now be more easily intercepted after they had breached the border. The strength of the individual legions was continuously reduced (eventually to around 1,000 men), for this purpose additional legions and independently operating elite groups were set up, including the so-called auxilia palatina . The proportion of mounted units, now called vexillationes , increased. The move created flexibility as troops could now be moved quickly without exposing the borders too much. Increased recruitment among non-Reich nationals (especially Germanic peoples ) was necessary to cover the personnel requirements. Some historians like Ammianus Marcellinus disapproved of this development, but Constantine's Germanic policy was quite successful. The main army (comitatus) accompanying the emperor was supplemented by guards if necessary. The guards of the scholae palatinae , which later comprised several units, were reorganized. The command structure has also been changed. In the border area, the dux was responsible for the security of a province , while civil administration was delegated. The command of the moving army was assigned to the newly created army master's office . There was a magister peditum for the infantry and a magister equitum for the cavalry, but in fact every army master commanded units of both branches of the army. In rank they were above the duces . After Constantine's death, the field army was divided regionally, so that there were several army masters in the most important border regions, especially in Gaul and in the east.

In 318/19 Constantine's son Crispus successfully took action against the Franks and probably also the Alemanni on the Rhine. Coins from the years 322 and 323 suggest that campaigns against the Teutons in the Rhine area were also carried out during this period. The danger of civil war was averted; the usurpation of Calocaerus on Cyprus in 334 was only a minor local event. The Rhine and Danube borders were stabilized. The high point of the security measures on the Danube was the construction of the bridge at Oescus in 328. A fortified bridgehead was built there. From outside the empire was no longer exposed to any serious threats until the beginning of the Persian War; it was now secure and militarily strong as it had not been since the 2nd century.

328 Alemanni were repulsed in Gaul. In 332 Constantine defeated the Goths and secured the Danube border with a treaty ( foedus ) . Contrary to earlier considerations, this was not yet associated with the elevation of the Goths to membership of the Reich Federation . Rather, the treaty, which was based on the usual framework conditions of Roman Germanic politics, obliged the Danube Goths only to provide arms and effectively eliminated a potential threat. In 334 Roman troops successfully attacked the Sarmatians .

Religious politics

Constantine and Christianity

From Sol to Christ

Constantine's religious policy, in particular his relationship to Christianity , is still controversial in research today. The special literature on this has assumed a barely manageable scope, and there is hardly any point where there is really agreement.

It is unclear why Constantine promoted Christianity relatively early. Until his time, Christianity was temporarily tolerated and persecuted in the Roman Empire. It differed from the pagan (pagan) cults primarily through its monotheism and its claim to sole possession of a religious truth leading to salvation . By the early 4th century Christians were already a relatively large minority. The tendency towards henotheism (concentration on a single supreme deity) that has emerged in pagan cults since the 3rd century bears witness to a growing susceptibility to monotheistic thinking. In the eastern part of the empire the Christians were more numerous than in the west, in Asia Minor some cities were already completely Christianized. The estimates for the proportion of Christians in the Reich population fluctuate greatly, a maximum of 10% should be realistic. It should be noted, however, that at this time by no means everyone who worshiped the Christian God did this exclusively; For many decades there were still numerous people who were only among others Christians: not everyone who saw himself as a Christian at that time was so also according to later understanding, which calls for strict, exclusive monotheism. This is also to be considered when considering Constantine's relationship to non-Christian cults.

Before the battle of the Milvian Bridge , Constantine, who had been inclined to henotheism since his youth, especially worshiped the sun god Sol Invictus . Christianity was known to him at least superficially at the time. From 312 he favored it more and more, with Bishop Ossius of Córdoba influencing him as an advisor. This new direction in the emperor's religious policy is known as the Constantinian turn . The question of the extent to which the emperor identified himself with faith remains open, especially since recent research, as I said, emphasizes that in the early 4th century it was by no means as clearly defined as today what was meant by a Christian and Christianity may be. If Constantine attributed his victory in 312 to divine assistance, he was still moving in traditional ways and only chose a different patron god than his predecessors. Several sources suggest a personal closeness to Christianity at this time, but evaluating the traditional reports is difficult because of the tendentious nature of both Christian and pagan sources.

Even pagan authors like Eunapios von Sardis do not deny that Constantine professed to be the Christian God. In his biography of Constantine, Eusebios von Kaisareia paints the image of a convinced Christian, which is certainly also based on the emperor's self-portrayal. On the Arch of Constantine , which celebrates Constantine's victory at the Milvian Bridge , only the goddess of victory Victoria and the sun god appear from the otherwise usual pagan motifs ; there are clearly no Christian symbols. This can be interpreted in different ways. Constantine may have ascribed the victory to a supreme deity (the summus deus ), which he did not necessarily and exclusively equate with the Christian god. But it is also possible that out of consideration for the pagan majority in the West, he renounced Christian motives. Pagan elements probably still played a role in Constantine's religious thought at that time; this phase is therefore also referred to as "pagan Christianity". The sun motifs on the triumphal arch can also be interpreted in a Christian way; It can be assumed that an ambiguity was desired in terms of religious policy and was therefore intended.

Sol coins were apparently only rarely minted from 317 onwards, and pagan inscriptions on coins also disappeared during this period. Around 319 the minting of coins with pagan motifs was stopped. The last known special issue with a representation of Sol was made in 324/25, it is probably connected with the victory over Licinius. The Sol motif did not disappear completely, however, because Constantine was still depicted based on Helios . Just as Christ was considered "the true sun" in late antiquity, so Constantine was also able to tie in with the symbolism of the worship of Helios. He demonstratively dropped the pagan surname Invictus in 324. In 321 Constantine declared the dies solis ("sunny day") to be a day of celebration and rest; he ordered the courts to be closed on the venerable "Sun Day". Before that, Sunday had a meaning for Christians as well as for Pagans, but it was not considered a day of rest. Recent research emphasizes the Christian aspect of this measure by Constantine.

In Constantine's time, “solar monotheism” and Christian belief were seen in some circles as closely related religious directions. No self-testimony by Constantine suggests a single experience of conversion, but it is quite possible that he felt himself to be a Christian at an early age. The sources hardly allow definitive statements about what Constantine understood by "his God". At first it may have been a mixture of different traditions and teachings ( syncretism ), including Neoplatonic elements. But there is also a line of research according to which Constantine was actually a Christian as early as 312. Constantine's “path to Christianity” was probably a process in which he finally came to the Christian faith via the sun god after a period of “limbo”.

In the opinion of most researchers, Constantine's Christian creed was meant seriously at least from a certain point in time; regardless of the open questions of interpretation, it corresponded to his personal convictions. What is certain is that after 312 he no longer promoted pagan cults and increasingly avoided pagan motifs. Already in the Panegyricus of 313 there was no mention of a pagan deity. The Milan Agreement of 313 did not yet privilege Christianity, but from then on Constantine actively promoted the Christian Church - first in the West, later in the empire as a whole - also by strengthening the position of the bishops. Christian self-testimonies of the emperor can already be found for the period 312/14. The so-called silver medallion from Ticinum with the Christ monogram and possibly a cross scepter (which could, however, also be a lance) dates from the year 315 . In addition, there was early support for the construction of the Lateran Basilica. After gaining sole rule, Constantine made clear his preference for the Christian God more clearly than before. His donations to the church were also intended to partly contribute to the fulfillment of the growing charitable tasks of the Christian communities. A decisive change in the course was that Constantine had his sons raised in the Christian faith. Increasingly, Christians were entrusted with important offices.

At the latest after the achievement of sole rule in 324, the emperor openly professed Christianity; more precisely: he presented himself as a follower and beneficiary of the Christian God. He probably regarded the Christian God as the guarantor of military success and general well-being. Thanks to his support for the Church, Constantine was able to rely on a solid organizational structure, which in part had developed parallel to the state administrative structures that were rather weak by today's standards. In addition, Christianity, whose representatives could also argue philosophically and thus address educated circles, made it possible for the ruler to underpin his claim to power religiously: since it was founded by Augustus, sole rule in Rome had always been questionable and precarious; Christian monotheism, with its position formulated at an early stage, offered a new basis for the legitimation of monarchical rule, as in heaven, so on earth only one should rule. Finally, Constantine even let himself be described as Isapostolus ("like the apostles"). His sacred empire was not linked to the explicit claim that the ruler was above the law. His followers continued on this path to divine right .

The emperor as mediator: Donatist dispute and Arian dispute

For Constantine there were some difficulties in connection with his new religious policy: As early as 313, the emperor had been confronted with the problems of the Church in Africa , where the Donatists had split off from the Orthodox Church. The background was the previous burning of Christian books during the Diocletian persecution of Christians. Some clerics had delivered Christian writings and cult objects to avoid the death penalty. The question now was how to deal with these so-called traders . Shortly after Caecilianus was ordained bishop in Carthage , African bishops met and declared the ordination invalid because an alleged traditor named Felix had been involved in it. Instead, Maiorinus was elected as the new bishop of Carthage, whose successor was Donatus in 313 . However, numerous bishops outside Africa supported Caecilianus and there was a split in the church on site. The so-called Donatists insisted that the traditors were traitors to the church and that their ordinations and sacraments were invalid. When it was decreed in 312 that the goods confiscated during the Diocletian persecution were to be returned to the churches, the dispute escalated: Which group represented the "real" Church of Carthage and was therefore entitled to money and privileges?

Various individual questions of the Donatist dispute, including the exact direction of the Donatists, are controversial because of the unsatisfactory source situation in research. In any case, Constantine intervened as the protector of Christianity and guardian of inner peace. As early as 314 he invited several bishops to Arles for a consultation on contentious issues. The council decided, following the decisions that had been made decades earlier in the heretic controversy , that a priestly ordination was valid regardless of the personal worthiness of the consecrator, even if he was a traditor, and decided the conflict in favor of Caecilian. The disputes in North Africa were by no means over. In 321, in the run-up to the final battle with Licinius, Constantine declared that he would tolerate the Donatists, but he soon took action against them to force an end to the conflict, albeit unsuccessfully. The Donatists maintained their position in North Africa for a long time and at times even made up the majority of North African Christians.

Constantine probably did not always recognize the full scope of the complex theological debates and decisions that would also cause many problems for his successors. He underestimated the potential for conflict inherent in dogmatic disputes. Rather, he seems to have understood the religious aspect of his empire according to a simple conventional pattern, with the Christian god having the function of the personal patron god of the ruler, which Iuppiter or the sun god had previously performed. However, Constantine's theological knowledge should not be rated too low either; In the Donatist dispute he was probably poorly informed at first, but later he apparently acquired some specialist knowledge. His approach to this difficult dispute, in which theological and political motives were mixed up, shows his efforts - albeit ultimately in vain - to find a viable solution.

Constantine also tried to resolve the second major internal Christian conflict of his time, the so-called Arian dispute . This controversy weighed even more heavily on his religious policy than the Donatist dispute, as it affected the richest and most important provinces of the empire.

Arius , a presbyter from Alexandria , had stated that there was a time when Jesus did not exist; consequently God the Father and the Son could not be of the same essence. This question was aimed at a key point of Christian faith, the question of the " true nature of Christ ", and was by no means only discussed by theologians. Rather, the dispute grabbed broader strata of the population in the period that followed and was sometimes conducted very doggedly; in Alexandria, especially Alexander of Alexandria opposed Arius. However, the transmission of sources is problematic and sometimes very tendentious with regard to many related questions: Neither the writings of the learned theologian Arius nor the later acts of the council of 325 have survived. To make matters worse, the often used collective term “ Arianism ” or “Arian” is very vague, as it was understood to mean extremely different theological considerations.

After gaining sole rule, the emperor was forced to deal with the conflict over Arius and with his views, because the initially local conflict in Egypt had rapidly expanded and was lively discussed in the east of the empire. Several influential bishops stood up for Arius, including the church historian Eusebios von Kaisareia. On behalf of the emperor, the aforementioned Ossius was supposed to sift through the situation and reach an agreement, but his exact role during the Synod of Nicomedia is controversial. This synod, at which the previously excommunicated Arius was accepted back into the church, did not achieve a sustainable solution anyway.

The intervention of Constantine in the dispute with Donatists and Arians is a clear sign of his new self-image to exercise a kind of protective function over the church and accordingly act as a mediator in internal Christian disputes. After the empire was politically united again after 324, the religious unity of the religion favored by Constantine was to be ensured. Constantine made use of its new imperial Synodalgewalt and called 325 a general council in the city of Nicaea (Nikaia) a.

The Council of Nicaea and its Consequences

The Council of Nicaea, which met in May 325, was the first ecumenical council . Over 200 bishops were present, mainly from the Greek-speaking East. They dealt - in the opinion of several researchers under the chairmanship of Constantine - above all with the Arian dispute . In addition, it was also about setting the Easter date, which had expanded into an Easter festival dispute. The majority of those who attended the Council appear to have been averse to extreme positions. In the end, the so-called Confession of Nicaea was adopted, according to which the Logos of Jesus' emerged from the being of God the Father and not, as Arius said, from nothing. He is "true God of true God", begotten, not created. The central formula of faith for the nature of Christ was now homoousios . This means "being of essence" or "being of the same nature"; the vagueness of this formula was probably intended to enable a consensus. The majority of the bishops decided against the teaching of Arius, but rehabilitated some of his followers. Arius himself, who refused to sign, was excommunicated and banished. Since the resolutions were ambiguous, renegotiations soon became necessary to clarify disputed points.

Arius was rehabilitated in 327/28. Whether he was convicted again in 333 is controversial in recent research. Konstantin acted flexibly in the complicated situation and avoided defining himself precisely. In this dispute there were numerous intrigues and defamations on both sides. Eventually the emperor changed his position, influenced by the Arian bishop Eusebios of Nicomedia . Arius had presented the emperor with a confession in which he avoided the statements condemned in Nicaea. Now his opponents got on the defensive; several of them, including their prominent spokesman Athanasios , the bishop of Alexandria, were banished. This seemed to give the Arian side an advantage, but Arius and Constantine died shortly afterwards (336 and 337, respectively). The Arian controversy continued until the Arians were finally defeated at the end of the 4th century.

Constantine and the traditional cults

The Constantinian turning point had consequences for Constantine's relationship to the traditional pagan cults, which by no means represented a unit, but were extremely heterogeneous. As Pontifex Maximus , the emperor was still responsible for the previous Roman state religion and the majority of the imperial population was still pagan. Constantine's protection of Christians resulted in numerous conversions at court. However, there are hardly any indications that the emperor planned to discriminate against or even forbid the traditional cults; the contrary assertions in Eusebios are of dubious credibility. Eusebios reports of a general ban on pagan sacrificial services in 324 and later Constantius II referred to a relevant law of his father, but the truthfulness of this information is very controversial. In the rest of the tradition there is no reference to this and the pagan speaker Libanios expressly states that Constantine confiscated goods, but did not restrict cult activities. Several modern researchers reject Eusebius' statement. Evidently Eusebios exaggerated in his description of Constantine's measures to reinforce the Christian stylization of the emperor. It is possible that Constantine only banned bloody victims, which he apparently refused, in the state.

While the great cults (especially the Mithras and sun cults ), which continued to have numerous followers in the army and in the imperial administration, remained unmolested, Constantine occasionally used state violence against pagan institutions and had a few temples closed or even torn down. The background for this requires a differentiated consideration. The few documented incidents concern the Temple of Asclepius in Aigai and primarily the Aphrodite cult associated with temple prostitution , for example in Aphaka in Phenicia and in Heliopolis . For Christians, the closure of these temples may indicate an anti-pagan attitude on the part of the emperor, but it should be noted that the cult of Aphrodite was offensive to many pagans and the closure did not seem to have met any resistance. The only documented case of Constantine's action against pagan cult institutions in favor of Christians is the overbuilding of a pagan cult site during the construction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem .

Constantine sometimes proceeded quite rigorously against Christian heretics , as they endangered the unity of the religion he favored and privileged, but the pagan practice of cult remained largely undisturbed. In this way, pagan sacrifices could usually continue to be carried out. However, for example, private haruspicos and certain rituals understood as magical were forbidden. In 334/35 Constantine still allowed the city of Hispellum in Umbria, in the tradition of earlier emperors, to build a temple dedicated to the imperial family. But he attached importance to certain restrictions on cultic veneration; so no sacrifices to gods were allowed to take place in his honor. Although Constantinople was planned as a Christian city, he allowed the construction of Pagan cult buildings there. There is no record of any discrimination against Pagan officials on the basis of their beliefs. In the state sector, however, the pagan elements were reduced as much as possible: The emperor increasingly had portraits removed from himself, forbade sacrifices in sovereign acts and possibly even abolished the practice of sacrifice in the army, in which Sunday prayer was introduced, probably all the more so for Christians to win for military service. The elevation of the Sunday to the public holiday of 321 may also indicate a tightrope walk on the part of the emperor, who wanted to appear to both Christians and pagans as one of their own.

In general, it can be said that Constantine promoted Christianity without confronting other religions or suppressing them. A detached and sometimes critical attitude towards the pagan cults can be seen at the latest since 324. Unlike the Constantine described in Eusebios, the historical emperor was probably a politician who acted strongly on the basis of considerations of political expediency. Nevertheless, the privilege he initiated for Christianity hit the pagan cults hard. Before that, they had by no means been in decline, but the trend was more and more towards henotheism or "pagan monotheism".

Judaism

The Judaism kept under Constantine the privileges enjoyed since the beginning of the imperial period. Constantine's policy towards the Jews was quite different. He allegedly prevented a new temple from being built in Jerusalem. What is certain is that he legally protected Jews who had converted to Christianity from reprisals by their Jewish fellow citizens and forbade non-Jewish slaves from being circumcised by their Jewish owners. Conversions to Judaism were made more difficult. On the other hand, Jews were now apparently allowed to join the city curia (as evidenced by an imperial decree from 321). Several Jewish clergy were even released from official duties.

Preparations for a Persian war and death of the emperor

In late antiquity, the New Persian Sāsānid Empire was Rome's great rival in the east. Most recently, there had been heavy fighting under Diocletian, which could only be settled for the time being in the Peace of Nisibis in 298/299 (see Roman-Persian Wars ). The Constantinian turning point also had an impact on the relationship between the two great powers, especially in the continually disputed Caucasus region . This region had increasingly come under Christian influence, which the Persian King Shapur II apparently felt threatened, as he now had to expect his Christian subjects to support Rome. Shapur invaded Armenia in 336, expelled the Christian King Trdat III. and installed his own brother Narseh as the new ruler. Constantine sent his son Constantius to Antioch and his nephew Hannibalianus to Asia Minor and prepared a great Persian campaign for the year 337.

It is unclear what Constantine planned in the event of victory. Hannibalianus was supposed to become the client king of Armenia as rex regum et Ponticarum gentium . Perhaps Constantine even intended to conquer the entire Persian Empire and make it a Roman client state. The war purportedly served to protect Christians in Persia. It is possible that the Alexander imitation also played a role in Constantine's thinking . In any case, the Persian advance required an answer. Ammianus Marcellinus gives the so-called " lies of Metrodorus " as the reason for war . According to this incredible episode, a Persian philosopher named Metrodorus, who had lived in India for a long time , came to Constantine with valuable gifts from Indian princes. He claimed the Persians had stolen several presents from him. When Shapur did not hand over the presents, Constantine prepared for war.

In the middle of the preparations for war the emperor fell ill and died soon afterwards on Pentecost 337 near Nicomedia . He was baptized on the death bed by the “Arian” Bishop Eusebios of Nicomedeia . Late baptism was not uncommon; it had the advantage that one could die as sinlessly as possible. After his death, Constantine was raised to divus in the sense of the Roman tradition - and like several explicitly Christian emperors after him . After his divinization, coins were minted showing his veiled portrait on the obverse. For centuries, a veiled portrait, along with the designation DIVVS, was the most striking feature of an emperor who was divinized after his death. On the back, the hand of God is offered to Constantine. On the one hand, these coins still refer to traditional polytheistic notions of gods, while on the reverse, with the hand of God ( manus dei ) clearly superior to the emperor, they already adopt Christian symbolism.

Constantine appointed his three sons Constantine II , Constantius II and Constans to be Caesars at an early age. His nephew Dalmatius also received this title in 335 . Perhaps Constantine had favored a dynastic rule of four for his successor, in which Constantine II and Constantius II would have acted as senior emperors. After his death, however, there was a family bloodbath and fratricidal war between his sons (see Murders after the Death of Constantine the Great ). Constantius II, who succeeded Constantine in the east, took over the defense of the Persians.

Aftermath

Late ancient judgments

Constantine is one of the most important but also most controversial people in history. Even in late antiquity, the assessment of his person and his politics varied considerably, which largely depended on the religious point of view of the respective observer. For the Christians, the rule of Constantine was a decisive turning point, so they were extremely grateful to the emperor. In his work De mortibus persecutorum (around 315), Lactantius expressed his joy at the end of the persecution of Christians in a more general way and thoroughly linked with anti-pagan polemics. He attributed the elevation of Constantine to emperor directly to the rule of God. Eusebios von Kaisareia , who wrote a little later, praised the emperor explicitly and exuberantly in his church history and, above all, in his biography of Constantine. He described him as a staunch Christian who experienced a dramatic conversion through the "vision" before the battle of the Milvian Bridge. The tendentious and exaggerated image of Constantine conveyed by Eusebios was very effective, especially since it stylized the emperor as the ideal Christian ruler. The work also conveys important information without which no story of Constantine could be written.

The generally positive Christian assessment continued in the various late antique church histories, for example with Socrates Scholastikos , Sozomenos and Theodoret , and later also with Gelasios of Kyzikos . They took up the image conveyed by Eusebios and portrayed Constantine as a pious Christian ruler. This image of Constantine also had a strong effect in Byzantine historiography. Critical voices can only be found sporadically, as in Jerome's Chronicle . In connection with the Arian dispute, Athanasios and some of the authors who followed him came to a partially critical assessment. Despite a largely positive account, Constantine's lately pro-Aryan policies were viewed rather disapprovingly. The church historian Philostorgios , who was active in the early 5th century and a “radical Arian” whose work shows traces of the processing of Pagan sources, offers an assessment of the emperor that differs slightly from the prevailing view.

The contemporary pagan historian Praxagoras praised the emperor panegyric ; he probably also introduced Constantine's nickname "the great". Otherwise, the judgments of the surviving pagan historians were mostly negative. Constantine's nephew Julian , the last pagan emperor (361–363), criticized him sharply and blamed Christianity for the bloody events of 337. Libanios and Themistios complained about high taxes and the associated alleged greed for money by Constantine, but such accusations are common topoi in ancient literature and are not particularly meaningful. Pagan authors polemicizing against Constantine's religious policy blamed him in various ways for various negative events. The privilege of Christianity is not mentioned in the various breviaries (brief historical works) of the 4th century, but here Constantine appears to be a capable ruler who could demonstrate military successes. The passages relating to Constantine in the great historical work of Ammianus Marcellinus (end of the 4th century) have not survived, but traces of an anti-Constantinian polemic can be found in the surviving parts. The historians Eunapios of Sardis (around 400) and Zosimos (around 500) attacked the emperor particularly hard ; for them he was "downright the gravedigger of the empire". Zosimos particularly emphasizes the family murders of 326 and thus explains - historically incorrect - Constantine's turn to Christianity. For the time before 324 he portrays him as a capable ruler who could only celebrate his successes with divine assistance and whose bad sides have not yet come to light. He confessed to the Christian faith very late, after which he became a tyrant.

middle age

The lasting victory of Christianity meant that the image of the emperor handed down by Christian authors prevails to this day. In the Byzantine Empire , Constantine was considered the ideal of a pious, just and strong ruler and was honored as the founder of the capital - he was "the emperor" par excellence. Ten Byzantine emperors were named after him . Not least for reasons of legitimacy, reference was made to him. The designation of an emperor as the “new Constantine” was programmatic, which has already been documented for several emperors from late antiquity. In Greek literature Constantine was treated intensively and praised, as his repeated mention in the library of the Byzantine scholar Photios I in the 9th century shows: for example in hagiographical writings, anonymous vitae or in the various Byzantine world chronicles, e. B. with Johannes Malalas , Theophanes and Johannes Zonaras .