Mithras

Mithras is a Roman deity and, as a god figure, a mythological personification of the sun , who was worshiped in Mithraism . The name Mithras goes back to the god Mithra from Iranian mythology . However, the Roman Mithras has certain differences to the Mithra of the Iranian peoples , so that the two cannot be equated despite their common origins and only have an indirect relationship to one another.

Mithra in Persia

Mithra ( Avestian Miθra and Miθrō , old Persian Miθra , Middle Persian Mihr and new Persian مهر, DMG Mehr, Mihr ) has been in the area of the later Persian Empire since the 14th century BC. Chr. Occupied and in the early period probably largely identical (Vedic) with the ancient Indian god Mitra . The name Mithra means “contract” in Old Persian. In ancient Indian , Mitra means “contract” or “friend”. Both go back to the proto-Indo-Iranian word root * mi-tra- ("contract", "oath").

In the Persian Empire and India , Mithra was a god of justice and alliance and, since the time of the Parthians, also a god of light and sun . He was the leader to the right order ( "Asha" in the religion of Zoroastrianism) and also watched over the cosmic order, such as the change of day and night and the seasons . He cultivated the virtue of righteousness , protected the believers and punished the unbelievers. He was depicted on a chariot pulled by white horses. His weapons were a silver spear, he wore gold armor and was armed with arrows, axes, clubs and daggers . His club was a weapon against the spirit of evil Angra mainju ( Ahriman ). Its most important task was to protect royal happiness and divine grace.

Zarathustra allegedly fought the Mithra cult, but this is uncertain. On the other hand, the deity was already of great importance in the Achaemenid period ; Mithra was apparently one of the three most important gods in Iran early on. So the great king Artaxerxes II asks in his inscription in Susa Ahura Mazda , Mithra and Anahita for assistance. Mithra also appears in one of the oldest yašts of the Avesta , a hymn dedicated to this deity and bearing her name ( Mihr Yašt ).

In late antiquity , Mithra ( Mihr ) was one of the most important gods in Persia, alongside Ahuramazda ( Ohrmazd ) and Anahita ( Anahid ), and appeared in part in the rock reliefs of the great kings. At this time, at the latest, his worship had also been integrated into Zoroastrianism. Over time, the teachings of Zarathustra and those of Mithras' followers became increasingly mixed - especially among the magicians of the Sassanid period (from 224 AD). Since the reign of the Parthians, Mithra had also - as already mentioned - assumed some attributes of a sun god, such as a crown of rays.

Mitra / Mithras in Asia Minor

The first records of Mitra in Asia Minor are known from clay tablets from Ḫattuša , the capital of the Hittite Empire , on which a treaty between the Hittites and their neighboring people, the Mitanni , was concluded. On this, in the 14th century BC. Chr. Dated tablets applies Mitra as a patron of the contract. In the following centuries in Asia Minor the name Mitra / Mithra was Hellenized to Mithras. It is probably this variant of the cult from Asia Minor that would later form the starting point of Roman Mithraism.

Various names of rulers in the Pontic Empire and other Hellenistic monarchies as well as the Parthians are Mithridates = "Given by Mithra". The first, Mithridates I from Pontus, carried this name from 281 BC. Chr. Became known Mithridates VI. (Eupator), who made pacts between the Roman Empire and the Parthians for almost half a century .

Mithras in the Roman Empire

According to Plutarch , the Romans learned about the cult from pirates from Cilicia , who were led by Pompey in 67 BC. Were decisively fought against. The morally strict Mithras cult, which was exclusively geared towards men, subsequently entered the Roman Empire through Roman legionaries .

In modern research, however, the thesis is increasingly advocated (cf. in particular R. Merkelbach and M. Clauss) that the Roman Mithras cult was rather a Roman new creation that was only marginally influenced by the Iranian cult: In the 1st century AD A now unknown founder brought this new cult into being in Italy (more precisely: in Rome) with recourse to oriental elements.

In addition to this, there are other modern hypotheses about the origin of the Roman Mithras cult . In any case, this reached its climax in the 2nd and 3rd centuries and in the 4th century it was subject to the now state-sponsored Christianity , which was elevated to the sole state religion of Rome in 380 . It took even longer, however, before the cult was completely suppressed. In Baalbek , the great main temple of Sol Invictus Mithras was only abandoned in 554 after it was burned out after being struck by lightning.

How widespread the cult actually was and what social significance it had is controversial. It does not seem to have been a real competitor to Christianity, which has a completely different orientation and structure - if only because of the exclusion of women: While Christianity was often passed on from mothers to their children, the Mithras cult could only win new followers through mission.

mythology

Little is known about the Roman Mithras cult and its mythology. There are two main reasons for this: On the one hand, the cult in its Roman variant was a mystery religion , whose followers were strictly forbidden to tell or write down anything concrete about beliefs and rituals. On the other hand, victorious Christianity tried to suppress the memory of the Mithras cult. It is therefore almost impossible to be certain about the Mithraic cult (even if the research literature suggests otherwise). Almost everything is controversial.

Mithras was sent by a father god to save the world. He was born from a stone in a rock cave, which was called by the myths as Petra Genetrix ("mother rock"). Accordingly, one speaks of a rock birth . The Mithrean iconography depicts Mithras as a youth wearing a Phrygian cap . The inside of his cloak is often decorated like a starry sky.

Central in Mithrean iconography is the motif of a bull killing. For the representation and different interpretations of the bull-killing scene in Mithraism, see the article Tauroctonia .

Mithras as the sun god

Similar to how the Persian god Mithra had been worshiped as a sun god centuries before, Mithras was also often nicknamed Sol invictus ( Latin for "the undefeated sun god") by the Romans . Many ancient illustrations show Mithras as equal to or victorious over the sun god Sol . Since Mithras and Sol were not identical, the epithet should possibly express that Mithras of Sol had taken on the role of the cosmocrator (ruler of the cosmos). Between the 3rd and 6th centuries, the Sol Invictus Mithras was one of the most popular deities among Roman non-Christians.

Archaeological sites

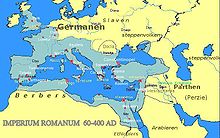

The Mithras temples are called Mithraea . Typically, they contained two long rows of loungers, separated by a central aisle that led from the entrance to the cult image. This showed the bull killing by Mithras, often supplemented by other scenes and symbols with controversial meaning. The Mithraea are relatively small, i.e. only aimed at small cult communities, and were apparently often not in use for long, so that their large number says nothing about the total number of followers. Apparently the cult community was not allowed to exceed a certain size; to avoid this, several mithraea were often founded in one place. They were largely destroyed with the Christianization of Europe and the associated end of Mithraism (the rest fell into disrepair), but their archaeological remains can still be found today throughout the territory of the Roman Empire, from the Iberian Peninsula to Asia Minor , from the British Isles to the North Africa coast . Quite a few mithraea have also been found in southwest Germany, for example in Saarbrücken and in Schwarzerden in Saarland , Dieburg and Heidelberg . There are also testimonies of the Mithras cult in the Bosnian Jajce .

A particularly well-preserved mithraum can be found in Italy, in the village of Santa Maria Capua Vetere (near Caserta ). It was discovered in 1924. The ceilings are painted and decorated with stucco and show motifs from the Mithras myth (including the bull killing by Mithras). Another preserved mithraium can be seen in the Roman city of Ostia Antica .

Source editions and translations

- Maarten J. Vermaseren (Ed.): Corpus inscriptionum et monumentorum religionis Mithriacae. The Hague 1956-1960.

- Hans Dieter Betz (Ed.): The Mithras Liturgy (= studies and texts on antiquity and Christianity. Volume 18). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2005 (text, translation and commentary).

literature

Overview representations

- Richard L. Gordon: Mithras. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 24, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-7772-1222-7 , Sp. 964-1009.

Overall presentations and investigations

- Roger Beck: The Religion of the Mithras Cult in the Roman Empire. Mysteries of the Unconquered Sun . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2006.

- Manfred Clauss : Mithras. Cult and mysteries. Philipp von Zabern, Darmstadt 2012, ISBN 978-3-8053-4581-1 .

- Thorsten Fleck: Isis, Sarapis, Mithras and the spread of Christianity in the 3rd century . In: Klaus-Peter Johne, Thomas Gerhardt, Udo Hartmann (eds.): Deleto paene imperio Romano. Transformation processes of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century and their reception in modern times . Steiner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-515-08941-1 , pp. 289-314 .

- Attilio Mastrocinque: The Mysteries of Mithras. A Different Account (= Oriental religions in antiquity. Egypt, Israel, Old Orient. Volume 24). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-16-155112-3 .

- Campos Méndez: El dios Mitra: orígenes de su culto anterior al mitraísmo romano . Ed. ULPGC, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2006, ISBN 84-96502-71-6 .

- Reinhold Merkelbach : Mithras. A Persian-Roman mystery cult . Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 978-3-928127-61-5 .

- Jean-Christophe Piot: Les Lions de Mithra. Gramond-Ritter, Marseille 2006, ISBN 2-35430-001-8 .

- Alexander von Prónay: Mitra: un antico culto misterico tra religione e astrologia. Convivio, Florence 1991.

- Michael Schütz: Hipparchus and the discovery of precession (remarks on David Ulansey: The origins of the Mithras cult ). In: Electronic Journal of Mithraic Studies ( uhu.es ; 53 kB).

- Elmar Schwertheim : Mithras. Its monuments and its cult (= ancient world , special issue 10). Field miles 1979.

- Robert Turcan : Mithra et le Mithriacisme. Les Belles Lettres, Collection Histoire, Paris 1993, ISBN 2-251-38023-X .

- David Ulansey : The Origins of the Mithraic Cult. Cosmology and Redemption in Antiquity . Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8062-1310-0 .

- Maarten J. Vermaseren: Mithras. Story of a cult . Stuttgart 1965.

- David Walsh: The Cult of Mithras in Late Antiquity: Development, Decline and Demise . Leiden 2019.

Web links

- Mithraic cult (Mehrayini) in Iran and in Europe

- David Ulansey: The Cosmic Mysteries of Mithras (English)

- The Mithras cult - scientific homework with presentation of the main features and the most important theories of the cult

- The iconography of Mithras (PDF, English) ( Memento from April 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (88 kB)

References and comments

- ↑ This name has other meanings in Middle and New Persian: "Light, Sun, Mercy, Friendship, Love" (cf. F. Steingass: Persian-English Dictionary. 6th edition, London 1977).

- ↑ Information on the illustration from: G. Herrmann. Archeology in words and pictures. Volume: The Rebirth of Persia. Licensed translation from the English original The Iranian Revival (1975), Elsevier Publishing Projects SA, Lausanne. Note: The identification of the right figure as Ahura Mazda is controversial in some sources. It is possible that Ardaschir's predecessor Shapur II is also shown, in whose army Ardaschir II participated as a general in the victory over the Roman emperor Julian the Apostate in his Persian campaign . The defeated Roman Emperor could thus be identified at the feet of the great king.

- ↑ Late Antiquity: Roman History from Diocletian to Justinian, A.D. 284-565 . CH Beck, 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55993-8 , pp. 502 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Source is missing!