Chariot

A chariot was in the Bronze Age and ancient one with horses strung, mostly uniaxial military vehicle . It was also used for representation and competition purposes.

Appearance and history

The chariot was invented by the bearers of the Sintaschta culture (also Sintaschta-Petrowka culture or Sintaschta-Arkaim culture) in the steppes , where the four-wheeled chariot previously had one of its origins. However, it was only used for a short time in the steppe, because soon mounted warriors were deployed. Were the Sumerians in the 3rd millennium BC. Heavy two- or four-wheeled wagons with disk wheels were still used, from the 2nd millennium BC onwards. BC two-wheeled chariots with spoked wheels were used. They were until about the 5th century BC. Commonly used. Britons , Persians and Indians used it at least until around the time of the birth of Christ, the Persians also used sickle chariots, which were equipped with blades on the axes. In the Middle Ages , heavy carts that were used to cover riflemen were sometimes referred to as chariots.

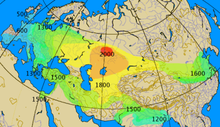

The chariot was also a status symbol of rulers in ancient times. The ancient chariot races were four-horse vehicles discharged while military vehicles used mostly two teams were. The first chariot dates from the second millennium BC. The chariot motif appears repeatedly on numerous vase paintings, clay tablets or pieces of jewelry. Images can be shown both real and supernatural. The origin of the chariot is controversial in research: Various archaeologists and scientists speculated around 1930 that the chariot must have come from eastern Anatolia . Later the conjectures were aimed at the mountain landscapes of Anatolia and Armenia . Others suspected the origin in the region around the Caucasus . With the scientifically carried out radiocarbon method , however, the knowledge about the area of origin shifted to an area of southern Russia , which must then have spread into eastern Europe.

The chariot of the second millennium BC BC, was now much lighter, but its design was initially kept very simple and consisted of two wheels and a simple bridge for attachment to the horse. The spoked wheel replaced the heavier disc wheel and was also used in the second millennium on a chariot, relief in the great temple of Abu Simbel (approx. 1265 BC). Since initially no mouthpieces were used for draft animals, a kind of halter was introduced, as the previously used nose rings and the shoulder straps used specifically for oxen and other draft animals were too heavy for the horse. Later a “yoke saddle” was added, which was specially adapted to the stature of the horse and was placed on the neck of the animal. In addition, a waist belt was introduced, which, like the new halter, should serve to relieve the weight to be carried.

The number of chariots in the early Bronze Age was low overall, but in Knossos alone “120 with wheels, 41 without wheels, 237 without a specific description”, ie around 400 chariots, were recorded. Therefore, the chariot must have developed into a very present object in the later Bronze Age.

Location of the chariot

The four-wheeled Sumerian chariots are not yet considered to be chariots. Later users of the chariot in Mesopotamia were the Mitanni , from whom the Hittites and Assyrians took it over. The chariot came to Egypt through the Hyksos . Between the Hittites and Egyptians it came about in 1274 BC. In the battle of Kadesch for the most famous use of chariots. The Old Testament mentions the use of chariots several times, sometimes expressly as "iron chariots". They are also mentioned in the Rigveda , which confirms their existence when it was created in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. In India. Archaeological evidence can only be found there for the sixth century BC. BC, which can be explained by the poor conservation conditions determined by the climate. Chariots also appear in China at a similar time. The oldest chariot grave (not chariot grave ) dates from 1200 BC. At the time of the Shang Dynasty . However, there are indications that as early as the time of the Xia , around 1600 BC BC ended, chariots were used.

In Western Asia and Europe, around the middle of the first millennium BC, Chr. Persians and Celts the chariot and used it for a long time. The ancient Persians were feared for their scythe chariots or sickle chariots with sharp blades on their wheels . However, the disciplined infantry of Alexander the Great's army had effective strategies against the scythe chariots, so that in 331 B.C.E. In the battle of Gaugamela were ineffective. Then came in the army of the Pontic king Mithridates VI. chariots with scythes probably still in use. In Europe, the Celts were the last to use the chariot called essedum in battle. The last known military use of chariots took place in 83/84 AD in the battle of Mons Graupius on the Celtic side.

Tension

In the Roman Empire, a chariot with two horses was called a biga , and one with three horses was called a triga (see Trigarium ). A team of four is called a quadriga . The driver of a biga is called Bigarius . The common name for a chariot driver is auriga . The special thing about the chariot tension is that the horses walk next to each other and not one behind the other.

The types of wagons

In the development of the chariot there were different types of chariots, which only appeared in a certain period of time. With a duration of 250 years, the “dual chariot” is the longest-running type of chariot.

Box chariot (1550-1450 BC)

A picture of a “box chariot” was found on a ring in Mycenae from the second half of the 16th century. The car consisted of a solid body and had a rectangular shape. The wheels had four spokes and the car was designed for one or two people. The side pieces of this wagon were about waist high and the railing lay horizontally and mostly beveled on the sides. The side pieces were mostly provided with different braiding patterns: especially in this case it was a cross pattern. The floor had the shape of the capital letter "D", which was also used in later types of car.

Quadrant chariot (1450-1375 BC)

The "quadrant chariot" was based on images of a seal stamp from Knossos around 1400 BC. Found. It rather shows a round body, like a "quadrant of a circle" - a quarter of a circle. This car also has waist-high side pieces and four-spoke wheels. In addition, this type of car is very light and consists of wood and rawhide that have been warped by heat. The dimensions of the platform are estimated to be half a meter long and one meter wide, so that two men could stand in this wagon. The typical “D-shape” of the floor was adopted here from the “box chariot”. The side parts of the car could either be completely free, closed or have cutouts. No complex braided patterns were used here.

Dual chariot (1450–1200 BC)

The third type of carriage of the “dual chariot” was found on wall paintings in Knossos around 1375 BC. Christ. The "dual chariot" again had a rectangular shape, but with rounded side parts that are attached to the front piece, the railing. Previously there was only room for two passengers in the chariot. In this type of car, however, there are also occasional images in which a third person can be seen. As a result, this type of car should have a larger standing area, whereby the typical "D-shape" was adopted here as well. The special feature of this car was a new axle drive, which was now connected to the car and foot section in three axes. With the materials of this type of car, wood was saved and more leather was used to make this car even lighter.

Rail chariot (1250–1150 BC)

The last type of wagon of the “rail chariot” was found on a vase from Mycenae from the second half of the 13th century. Its specialty is that its body consists only of a railing and the front and side parts have been left completely free. This type of car is certainly one of the lightest of its kind. However, the least information about this type is available, except that this type also has a four-spoke wheel and can transport one or two people. With this type of car, however, it was less likely that weapons would be carried, as they could fall out of the sides more easily.

Military use and object of prestige

Initially, chariots were troop carriers used to bring warriors in good physical shape to the battlefield. Later, more agile wagons were developed that actively intervened in the battle with spearmen and archers. From this point on, the tactical role of chariots was similar to that of armored personnel carriers in modern times. However, chariots could only be used on relatively flat terrain. Later they were replaced by the more flexible and cheaper cavalry .

Some chariots were intended for long-range combat, mounted archers fired at the enemy formations from a safe distance, and the chariot withdrew to a safe distance before the opposing troops got too close. In addition to this attrition tactic, there was also use in hand-to-hand combat, for which heavier wagons pulled by several horses were built, and the frame and wheel hubs were provided with blades. The sickles on the axles and the two to four horses made a massive impact into enemy lines possible, but horses rarely ride into closed combat formations . The psychological benefit - the foot soldiers' fear of an approaching chariot - should not be underestimated either. Similar to the common cavalry , the chariot had the ability to simply overrun open formations of soldiers. Riders, too, had to beware of chariots, because sickles were also a great danger to unprotected horse legs. In addition to this combat power, there were also long-range weapons and lances that were used from the chariot. Bows and javelins were used to fight from the chariot ; for hand-to-hand combat with swords and other weapons one jumped off. In case of danger, the charioteer returned so that the fighter could jump up again. The chariot fighter was usually aristocratic, as in ancient times weapons and equipment had to be provided by the fighter himself - a chariot with horses was very expensive. Chariot fighters are described in the Iliad . The charioteer did not usually fight himself.

Up to three occupants could ride in a chariot. Often the driver stood in front, who was protected by a shield by a second man , as the chariot had no cover to the rear. Ideally, a third person who has a combat weapon would accompany you to attack. The equipment mostly consisted of: whip, shield and bow. The driver also had a lance or sword with him. The uniform mostly consisted of a helmet and breastplate, which consisted only of leather, possibly to save weight. The chariot drivers belonged to the upper class of the population, as the acquisition and maintenance of a chariot team was associated with considerable costs. For the same reason, only wealthy regions could support a significant armament of chariots. A chariot driver needed extensive training in order to steer the chariot properly and to optimally distribute the balance, and the other occupants of the chariot also had to learn defensive maneuvers and combat tactics over a long period of time.

However, chariots were also used purely as a prestige object by kings and higher officers. This theory is supported by the various decorations in the form of wickerwork on the body of the chariot itself and the decoration of the spokes and wheels. In this regard, the chariot was primarily a sensational object and enabled kings and officers to move around in a visually superior and befitting manner. Formulations such as “leisure activity” and mentions as a pure means of transport also appear in ancient inscriptions.

In addition to the military and elitist benefits, hunting with a chariot was also important. There are already from the 18th to 17th Century BC Chr. Images of a Syrian top hat, on which drivers with the reins tied around their hips can be seen with a bow. However, this method would have been risky when driving faster, as the driver had almost no control over the car, which is why the chariot must have been used purely as a wagon and hunting vehicle.

Hittite chariots

The Hittite chariots - perhaps the most powerful weapon in the world in their time - were initially manned by two and later by three men: at first there was an archer and a charioteer who protected both with a shield, and later a third warrior was added, the Schild took over and was equipped for close combat.

A great advantage of the Hittite and Egyptian chariots, which were pulled by two stallions , was their light construction: The structure consisted of a wooden frame covered with leather and straps, on the axle two wheels with six spokes turned; only the heavily used wheel rims were more massive. This ensured that a single man could carry such a vehicle: A preserved Egyptian chariot that one in Florence can be visited, weighs only 24 kilograms (for comparison: a modern light metal - Sulky must not exceed 30 kilograms).

In contrast to the Persians, for example, the Hittites used chariots primarily as long-range weapons, from which one could shoot at the enemy and then withdraw quickly. Their occupation was also not an elitist caste , as was the case with many neighboring peoples (for example in Mitanni). It even happened that conquered teams including drivers were integrated into their own army. The Hittites were extremely dependent on their strongest weapon: a king even refused to pursue opponents in inaccessible areas and preferred to starve them - which took considerably longer - because his warriors could not carry the chariots on their backs - a fight Without a chariot it seemed impossible to him.

It is also a Hittite inscription that first mentions chariots: Great King Anitta went into battle with 40 of them. According to Egyptian sources, a full 3,500 were deployed in the battle of Kadesh - 7,000 horses and a crew of 10,500.

Mesopotamia and neighboring countries

In Akkadian , the car was called narkabtu or mugerru , and the driver was called rākib narkabti . It is usually assumed that two-wheeled chariots were used on a larger scale from around 1600 BC. Were used. Six- spoke chariots were built first, since Tiglath-pileser III. eight-spoke. In the year 839 Assyria was able to set up chariots in 2002.

The affiliation of the often very similar wagons could be emphasized by the tiller trim . New Assyrian chariots usually had a fan-shaped top, but this is also passed down from Aramaic city-states such as Sam'al . The tiller ornament of the Urartians , on the other hand, consisted of a “disk with 5 upright tongues”, which has been handed down both in the original (with Išpuini's ownership inscription ) and as a picture since Argišti I.

Aegean

In the Aegean, the chariot can also be identified from around 1600 ( shaft graves ). According to Drews, the terminology associated with the chariot is Indo-European .

Chariots are mentioned in many places in the Iliad ; According to the latest research, the combat technique of chariots presented in the epic represents the final stage of chariot use in combat. It can no longer be used in attack in closed formations, but in phases of highly mobile warfare it still has a limited range of uses, which has striking parallels to today's combat technique and tactics Has combat vehicles. During the Lelantine War , the chariot was already displaced by the cavalry in combat. The chariot was thus used in the Aegean from the Mycenaean epoch to the middle of the 8th century BC. Used as a combat vehicle.

mythology

Chariots play an indirect role in the mythology of various peoples. So in India the old Vedic gods like the sun god Surya or the wind god Vayu as well as Krishna are represented in Rathas ( Sanskrit for "chariot"). In Greek mythology , the sun god Helios rides a chariot across the sky.

Although there is no archaeological evidence of the use of chariots in Ireland , the island's mythical heroic poems almost always feature fighters as charioteers. The story Aided Chon Culainn ("The Death of Cú Chulainn ") tells of his charioteer Loeg mac Riangabra and the horses Liath Macha and Dub Sainglenn . Llyn Cerrig Bach's findings on Anglesey have archaeologically confirmed chariots for Wales . The work “Celts - Images of their Culture” shows Llyn Cerrig Bach's reconstructed chariot and drawings of chariots deployed.

literature

- Arthur Cotterell: Chariot. The Astounding Rise and Fall of the World's First War Machine. Pimlico, Random House, London 2005. ISBN 1-8441-3549-7 .

- Joost H. Crouwel: Chariots and other means of land transport in Bronze Age Greece . Amsterdam 1981. ISBN 9071211215 .

- Robert Drews: The Coming of the Greeks. Indo-European conquests in the Aegean and the Near East. 2nd printing. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1988, ISBN 0-691-02951-2 .

- James K. Hoffmeier: chariots. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 193-195.

- Robert Drews: The end of the Bronze Age. Changes in warfare and the catastrophe about 1200 BC . Princeton 1993. ISBN 0691048118 .

- Anthony Harding: Warriors and weapons in Bronze Age Europe . Budapest 2007. ISBN 9789638046864 .

- Anja Herold: Chariot Technology in Ramses City. (= Research in the Ramses City - The excavations of the Pelizaeus Museum Hildesheim in Qantir-Piramesse Vol. 3), Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-3506-7 .

- Valentin Horn: The horse in the ancient Orient. The chariot horse of the early days in its environment, in training and in comparison to the modern distance, riding and driving horse . Hildesheim 1995. ISBN 3487083523 .

- Annelies Kammenhuber: Hippologia Hethitica . Wiesbaden 1961. ISBN 9783447004978 .

- Mary Aiken Littauer: Selected writings on chariots and other early vehicles, riding and harness . Leiden 2002. ISBN 9004117997 .

- Thomas Richter: The chariot in the ancient Orient in the 2nd millennium BC BC - a consideration based on the cuneiform sources. In: Mamoun Fansa , Stefan Burmeister (Ed.): Rad und Wagen. The origin of an innovation. Wagons in the Middle East and Europe (= Archaeological Communications from Northwest Germany. Supplement 41). Isensee, Oldenburg 2004, ISBN 3-89995-085-2 , p. 507ff.

- Fritz Schachermeyr: Greek early history. An attempt to make early history understandable, at least in outline . Vienna 1984. ISBN 3700106203 .

- Frank Starke: Education and training of chariot horses. A hippologically oriented interpretation of the Kikkuli text . Wiesbaden 1995. ISBN 3447035013 .

- Rupert Wenger: Strategy, tactics and combat technique in the Iliad. Analysis of the battle descriptions of the Iliad (= series of ancient language research results. Vol. 6). Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8300-3586-2

- Michael Ventris: Documents in Mycenaean Greek . 2nd printing. Cambridge 1973. ISBN 0521085586 .

- Heike Wilde: Technological innovations in the second millennium BC. For the use and distribution of new materials in the Eastern Mediterranean region (= Göttingen Orient Research. Series 4: Egypt , Vol. 44). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2003. ISBN 3-447-04781-X , pp. 109–130 (At the same time: Göttingen, Universität, Master's thesis, 1999/2000).

- Heike Wilde: Innovation and Tradition. For the manufacture and use of prestige goods in Pharaonic Egypt . Wiesbaden 2011. ISBN 9783447066310 .

Web links

- Ulrich Hofmann: Cultural history of driving in the Egypt of the New Kingdom.

- Oswald Spengler: The chariot and its significance for the course of world history. Lecture given on February 6, 1934 at the Society of Friends of Asian Art and Culture in Munich. Zeno.org

- Andrea Salimbeti: The Greek Age of Bronze: Chariots. www.salimbeti.com, December 15, 2012, accessed January 12, 2013 (English).

Individual evidence

- ^ Fritz Schachermeyr: Greek early history. An attempt to make early history understandable, at least in outline . Vienna 1984. p. 107f.

- ↑ Thomas Richter: The chariot in the ancient Orient in the 2nd millennium BC BC - a consideration based on the cuneiform sources. In: Mamoun Fansa , Stefan Burmeister (Ed.): Rad und Wagen. The origin of an innovation. Wagons in the Middle East and Europe (= Archaeological Communications from Northwest Germany. Supplement 41). Isensee, Oldenburg 2004, ISBN 3-89995-085-2 , p. 46.

- ^ Fritz Schachermeyr: Greek early history. An attempt to make early history understandable, at least in outline . Vienna 1984. p. 77.

- ^ Michael Ventris: Documents in Mycenaean Greek . 2nd printing. Cambridge 1973. p. 365.

- ↑ Jos 17: 16-18 EU ; Ri 1.19 EU , 4.3 EU and 4.13 EU

- ^ Tacitus : Agricola. - Biography of Gnaeus Iulius Agricola , Roman governor in Britain.

- ↑ CIL 6.10078 and 6.37836.

- ↑ Joost H. Crouwel: Chariots and other means of land transport in Bronze Age Greece . Amsterdam 1981. pp. 59-61.

- ↑ Joost H. Crouwel: Chariots and other means of land transport in Bronze Age Greece . Amsterdam 1981. pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Joost H. Crouwel: Chariots and other means of land transport in Bronze Age Greece . Amsterdam 1981. pp. 63-66.

- ↑ Joost H. Crouwel: Chariots and other means of land transport in Bronze Age Greece . Amsterdam 1981. pp. 65-70.

- ↑ Frank Starke: Education and training of chariot horses. A hippologically oriented interpretation of the Kikkuli text. Wiesbaden 1995. p. 127.

- ^ Robert Drews: The end of the Bronze Age. Changes in warfare and the catastrophe approx. 1200 BC Princeton 1993. p. 105.

- ^ Fritz Schachermeyr: Greek early history. An attempt to make early history understandable, at least in outline. Vienna 1984. p. 100.

- ^ Robert Drews: The end of the Bronze Age. Changes in warfare and the catastrophe approx. 1200 BC Princeton 1993. p. 115.

- ↑ Brad E. Kelle: What's in a Name? Neo-Assyrian designations for the Northern Kingdom and their implications for Israelite history and Biblical interpretation. Journal of Biblical Literature 121/4, 2002, p. 642.

- ↑ a b P. Calmeyer / U. Seidl: An early Urartian representation of victory. Anatolian Studies 33, 1983 (Special Number in Honor of the Seventy-Fifth Birthday of Dr. Richard Barnett), p. 106.

- ^ Walter Andrae : The small finds from Sendschirli. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1943, pp. 79ff.

- ↑ Arch. Mitt. Iran 13, 1980, p. 75.

- ↑ Helmut Birkhan : Celts. Attempt at a complete representation of their culture. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-7001-2609-3 , p. 952.

- ↑ Helmut Birkhan: Celts. Images of their culture. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-7001-2814-2 , pp. 338 f, pictures 607, 608, 611.