Military in Ancient Egypt

The sources available on the military in Ancient Egypt essentially deal with military developments in the Old , Middle, and New Kingdoms . With the 3rd interim period began the increasing decline of central government control and organization as well as more and more the loss of one's own independence. This was accompanied by the economic, political and military decline of Egypt, as well as the slowly dwindling influence in Palestine , Lebanon and Nubia . This development after the end of the New Kingdom is also reflected in the less informative source material on the military .

In times of weak central power, the military system was shaped by the balance of power between the pharaoh , the princes and the priesthood, while the dominant pharaohs of the state pushed back the influence of the princes and the priesthood. A strong pharaoh not only ensured the country's prosperity, but was also the prerequisite for political and military expansion. However, the country's economic self-sufficiency during the Old and Middle Kingdom offered little cause for expansion into the Near East . It was the military capabilities that ensured the existence of Egypt and the longevity of its civilization.

The geostrategic location and geography of Egypt had a major influence on the development of the military. It borders the Sinai in the northeast and the Libyan Desert in the northwest , the Mediterranean forms a natural border in the north and the rocks of the first cataract in the south . Geographically, Egypt is an oasis of electricity , but in terms of transport technology, a river society developed from it. The Stromoasis character led to the use of boats for military purposes at an early stage. Shipping was supported by the river flowing from south to north and the almost constant wind blowing from the north, so that shipping was made easier in both directions.

The natural barriers allowed Egypt to live without any significant threat to its borders for almost a thousand years until the Hyksos came to power in the Second Intermediate Period . Before this event, there was no need for a standing army . This changed in the New Kingdom. A possible military threat to Egypt was reduced to the three gateways dictated by geography. None of these borders were insurmountable, but the natural obstacles made it difficult for a long time to access the military developments of other states beyond their immediate neighbors. The immediate neighbors, Nubians in the south, Libyans in the west and Bedouins in the east, were at least during the Old and Middle Empire at the same or lower level of weapon technology. During this time, therefore, the development of weapons technology in Egypt stagnated.

Old empire

Southern Syria and Palestine were viewed as Egyptian areas of influence in the Old Kingdom. There are no noteworthy characteristics of diplomatic and military activities in support of this claim. The nomadic inhabitants of Palestine and Libya did not pose a military threat. However, Nubia was seen as a threat. However, it was less developed militarily than Egypt. The necessity for the maintenance of armed forces , as seen by the pharaohs, resulted more from the provision for the national defense and the suppression of occasional revolts of the Gau princes and the population, since the political landscape in the united kingdom was co-determined by the power-conscious Gau princes and their own armed forces.

Organization of the armed forces

A verifiable military organization emerged for the first time during the Old Kingdom. The majority of the armed forces were under the command of the Gau princes and were organized in militia units. They were reinforced by Nubian mercenaries paid by the Pharaoh . For his own protection, the Pharaoh had a relatively small but standing guard force of several thousand men . The princes were obliged to provide the pharaoh with troops if necessary. The training was carried out regionally at the Gaue level and consisted only of basic training.

The first staff structures emerged. Assignments of tasks such as quartermasters, command designations such as commanders for military depots, special forces for the desert war, clerks as well as border and garrison tasks reveal function assignments. However, a clear, military hierarchy can hardly be determined.

Conscription and Order

The conscription was introduced in the Old Kingdom. Soldiers were drafted periodically and as needed. Recruitment was based on around 1 out of 100 male residents. The majority of the conscripts were used as garrison personnel in the border forts and for the construction of public projects. In addition, the soldiers were needed to work in the quarry, to protect expeditions, for military campaigns and to suppress civil unrest.

Military use of shipping

The river oasis character of Egypt led to amphibious warfare in Egypt and Nubia from the beginning . Already since 3000 BC Coordinated attacks from land and troops landed over the Nile were carried out against Nubian villages. The Egyptians used around 2450 BC. First ships to transport troops to Palestine.

The boats used were merchant ships. In the Old Kingdom, in addition to smaller boats, 21–32 meter long boats of the ship types satch and sekhet were used for transport purposes on the Nile . However, Egyptian boats could not navigate the high seas due to their design . So-called Byblos boats were used here, which were obviously named after their Syrian-Palestinian origin.

Armament

The military power of Egypt was based in the Old Kingdom on a largely constant and unchanged arsenal. It corresponded to that of the potential opponents in the immediate vicinity. Conquests in these areas were based more on better command and organization of the armed forces and greater manpower than on superior armament.

The main armament in the Old Kingdom were maces , battle axes , chepesh , bows and arrows , throwing spears, slingshots and halberds . The stone flask was the most common weapon in the Old Kingdom. Copper-edged maces and battle axes were the most effective weapons in hand-to-hand combat. Throwing wood, which in contrast to the boomerang does not return to the thrower, is also a traditional weapon, but was only used as a hunting weapon in the Old Kingdom. There were no armor for body protection in the Old Kingdom. The soldier's only protection was his shield.

Fortresses, siege techniques

Boo was probably Egypt's first fortified outpost in Nubia. It was a small settlement protected by a large, roughly built wall. It probably originated in the fourth or fifth dynasty, possibly as early as the second dynasty. One of the oldest forts in Egypt was built on the southern tip of Elephantine Island during the Old Kingdom. It was strategically located in the middle of the Nile just above the first cataract. The Nile gave the complex natural protection.

Opposing fortresses or fortified cities were stormed by ladders up to a height of 10 m or by undermining the walls. If these conquest techniques were unsuccessful, all that remained was the siege by starvation.

Administration, logistics and medical services

The military administration and organization as well as the logistics had been well developed since the beginning of the Old Kingdom by a centralized administration supported by clerks. The standard means of transport of the Egyptian army on land was the donkey, if boats were not used for transport anyway. There was no institutionalized military medical care. However, the princes' doctors treated their militiamen. The doctors did not serve as part of the military, but they have gained experience by accompanying high-ranking officers in the field. In addition, doctors at the court of the pharaoh and the princes were sometimes sent to military outposts to treat soldiers.

Middle realm

Southern Syria and Palestine were also viewed as Egyptian areas of influence in the Middle Kingdom. From the reign of Sesostris III. Egypt began to establish itself politically, militarily and economically as an international power in neighboring countries. Around 1790 BC BC the central government lost its power to the Gaufürsten, which the Hyksos , which had long since infiltrated into the delta, used to take power in northern Egypt.

Organization of the armed forces

In the Middle Kingdom, too, the princes controlled their militias based on conscription, but the power of the princes had been since Sesostris III. clearly restricted. Nubian mercenaries continued to serve in the armed forces. The Middle Kingdom army had a clearer command structure. The Pharaoh was in command of major campaigns. He appointed officers responsible for border defense and logistics . There were defined communication channels and reporting procedures. A military police was introduced in addition to district officers, military judges as well as a military intelligence service and file management.

Military use of shipping

The warfare in the Middle Kingdom retained its amphibious character. The main means of transport in Egypt remained the boat. The fleet was the dominant branch of the Egyptian armed forces with elitist claims. Members of the royal family served in it. Ship commanders were directly subordinate to the Pharaoh and his highest officials. The size of the boats remained unchanged at around 30 m in length, although the design features and rigging changed. These boats were also used in the New Kingdom. The transportability of ships on the Mediterranean was 200 men.

Fortresses

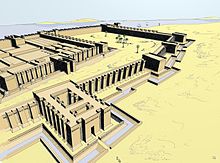

The borders of Egypt were secured against possible intruders by fortresses . The eastern delta since the reign of Amenemhet I , the western delta through a fortress in Wadi Natrun in the Sketian desert . These systems were built during the 2nd millennium BC. Chr. In good condition. In addition to the defensive provisions, the fortresses also served to protect trade routes and maintain the Pharaoh's trade monopoly.

In the south, on the border with Nubia, Egypt was secured not only by the existing fortresses but also by the fortified Elephantine . In the reign of Sesostris I to Sesostris III. at least 17 fortresses were built. Buhen fortress had a built-up area of 3000 m², surrounded by a 4.5 m thick and 9 m high wall with bastions every 5.5 m. Outside this wall was a second wall, which was designed as a sloping support wall with loopholes every 9 m. The gate was a good 18 m high and extended over the moat.

The land trade routes along the first and second cataracts were through during the XII. Walls built by the dynasty protected. Commercial establishments established in the Old Kingdom were fortified. Fortresses had storage rooms for significant amounts of grain, enough to feed a garrison for up to a year. The construction of the built fortresses corresponded to comparable facilities of the Middle Ages. The fortresses built close to the Nile had protected access to the water, which enabled both a supply via the Nile and access to water. Other fortresses had wells or cisterns . The fortresses were supplemented by strategically distributed watchtowers. The siege techniques remained essentially unchanged. During this time, covered battering rams were used to destroy the gates.

Medical service

Like weapons technology, Egyptian medicine was excluded from external influences for more than 2000 years until the Hyksos invaded. Egyptian medicine was associated with the temples, priests and the nobility and thus prevented the development of a military medical service . Egyptian medicine was at the height of its knowledge and effectiveness during the Middle Kingdom, although it never severed its connections with magic and religious mysticism. Doctors were familiar with wounds suffered in combat. Skull openings were one of the almost 100% successful operations. In the age of soldiers without helmets and armor and the use of maces, these were common injuries. More or less the same injuries as in civil life were successfully treated: straight and sunk fractures, cuts, bruises, contusions, fractures, amputations and open flesh wounds. The Egyptians were familiar with arm and greaves, sutures, washing out wounds, hemostasis, the use of bandages and bandages and the use of opium to relieve pain.

New kingdom

The Hyksos possessed advanced weapons technology from Mesopotamia, in particular chariots, composite bows, and metal-reinforced protective vests and helmets. This technology was also available in Egypt when the Hyksos came to power at the latest and led to quick acceptance and accelerated introduction, use and improvement of chariots in particular.

After the Hyksos had been driven out, the military means were available to force an imperial and expansionist power politics. The successful wars of liberation have considerably strengthened the position of the pharaoh and thus the central authority. Inevitably, this diminished the influence of the Gau princes on national politics. The foreign rule in parts of Egypt was an unequivocal warning not to lose political and military initiative to the Asian peoples. Political influence and military expansion into Syria-Palestine was imperative in order to build a buffer zone against this threat.

Consequently, the armament of the Egyptian army had to be radically modernized and brought up to the standard of potential opponents. A permanent conquest of Palestine was only possible through the creation of modern armed forces. For this purpose, the armed forces were rebuilt in quick succession. For the first time in Egyptian history, a professional military caste emerged.

The focus of the expansion was initially on Nubia up to the 3rd cataract and beyond. The conquests in Palestine and Syria were particularly favored in Palestine by the small territorial size and population of these kingdoms and the lack of strong allies. At the time of the New Kingdom, the population of Palestine was around 140,000, with its own population of around 2.9 million. A system of alliances and treaties and the establishment of a network of garrisons secured the Egyptian military and political influence.

Organization of the armed forces

After 3000 years of development during the New Kingdom, the Egyptian military system reached an almost modern standard of organizational maturity. The military forces were organized as a national standing army on the basis of military service, although regional militias continued to exist. The princes were no longer able to prevent troops from being raised. The vizier served as minister of war . The council of war served as the general staff .

With the end of the second intermediate period and the expulsion of the Hyksos, the armed forces were strengthened to three divisions and from the 19th dynasty to four divisions. The additional two divisions were stationed in the Heliopolis and Pi-Ramesse locations . The field army now consisted of two army corps of two divisions each. The divisions could be used individually or in association with other divisions. Each division consisted of 5,000 men. These associations were reinforced by allies and mercenaries when necessary. Mercenaries and allies formed their own units that were not integrated into the Egyptian units. The four divisions had their own names with corresponding symbols: the Ptah division the head of the Apis bull, the Re division the head of a falcon, the Seth division the head of a dog and the Amun division the head of a ram.

In addition to the armed forces, there were also the static border area units, which were stationed in the respective garrisons and were commanded by the local garrison commanders, the Idnu. The stationing of the armed forces was based on the two possible threat scenarios for the country in a North and South Corps. Units were also stationed in Nubia and Syria.

Military hierarchy

The military hierarchy has been known since Haremhab . The pharaoh was also the warlord on the battlefield. Subordinate to the pharaoh was the commander in chief , usually a son of the pharaoh. This is followed in the hierarchy by the army commanders of the North and South Corps, followed by the division commanders (title Imur-Meschta ) in the rank of general , very often royal princes. These are the "scribes of the infantry " and the standard bearers. This includes the brigade commanders and company commanders . Garrison squad leaders, group leaders, and common soldiers follow .

Conscription, Training and Mission

The army was composed of professional soldiers and conscripts who were only called up during wartime. However, the recruitment rate was 1 in 10 instead of the traditional 1 in 100.

The training was locally centralized and carried out by officers and non-commissioned officers at military academies . There was a chariot training facility in Memphis and Thebes. The infantry were trained for hand-to-hand combat as well as pioneering and siege operations. A distinction was also made according to level of training and task; such as recruits, fully trained soldiers and elite attack formations.

In addition to the military mission during war, the soldiers were deployed in peacetime to transport building materials and deployed in construction projects, to protect trade routes and expeditions to extract ore and precious metals, to guard inner Egyptian borders, to track down escaped prisoners and to perform scouting services.

Military branches, branches of service and structure

The reconstruction of the armed forces was carried out during the reigns of Thutmose I to Thutmose III. completed. The armed forces were divided into the troops of infantry , chariot units , garrison and outpost troops , elite troops , fleets and mercenaries. The infantry and chariot detachments were the main combat forces in the Egyptian army. A division had up to 10 brigades.

Brigades ( Pa-Djetu )

The brigades of a division were commanded by a Heru Pa-Djet ("Head of the Djet"). The strength of a Pa-Djet was between 500 and 1000 soldiers.

Regiment ( Sa )

The Pa-Djet was again divided into two regiments ( Sa-u ), which consisted of close combat troops and archers in equal parts. A regiment was led by a Tjah-Serut and consisted of 200 to 250 soldiers. Within the regiments, close combat soldiers formed further sub-units, which were called Nachtu-Aa ("the great strong ones ").

company

The regiments consisted of four to five companies of 50 soldiers each, further divided into 5 groups of 10 men. The leaders of these units were captains who, however, did not constitute an official military leadership title. Each company had its own standard , e.g. B. Ship personnel hold the ship and archery companies hold the bow. The companies differed in the type of armament, for example ax bearers , archers, club bearers and spear bearers .

The Chariot Corps ( Pa-Djetu )

The chariot corps represented the elite of the armed forces. The corps was divided into squadrons of 25 chariots, commanded by a “chariot driver of the palace”. Larger units of 50 and 150 cars could easily be put together and used in conjunction with larger associations. Also known is the division of the chariots into groups of ten, led by a "first charioteer", five troops formed a squadron under a "standard-bearer of charioteers". Several squadrons formed a regiment, led by a "commander of a chariot regiment". The chariot corps included lightly armed runners ( Pa-Hereru ) who accompanied the chariot drivers .

For reconnaissance purposes, there were armed mounted soldiers who were used as scouts and notifiers. In addition, the Pa-Hereru also acted as reconnaissance troops , who cleared up the enemy and carried out a battlefield investigation. In the New Kingdom the Nubian forts were under the command of the fortress commander von Buhen.

fleet

In the New Kingdom, Egypt had its own navy during the 18th Dynasty . Ordinary merchant ships, cargo ships and ships for coastal shipping were used. The crew was initially Egyptian. Already under Ramses II. The crew of the boats started by Shardana -Söldner. They were recognizable by their Aton sun discs on their helmets.

Under Ramses III. a large part of the Egyptian Navy was manned by mercenaries. The fight took place as hand-to-hand combat by throwing projectiles and using a bow and arrow and then boarding. During the war, however, the fleet only played a supporting role. The development of squadrons for naval warfare is unknown.

Under Ramses II and III. the ship type menesh , whose origin was in Phenicia, was common. Egyptian shipbuilding did not produce ocean-going ships. The existence of marines cannot be proven.

Armament

The political specifications of the now expansionist policy of the New Kingdom towards Palestine and beyond required a radically changed armament.

Chariot ( Wereret )

The previous amphibious warfare and the unsuitable terrain for the use of chariots in large parts of Egypt have not made it necessary to invest time or money in chariot technology. Chariots could only be used on flat terrain. Horses first appeared in Egypt. The construction of the chariots has been improved. The chariots were of lightweight design and weighed only about 35 kg; it took more than half a dozen different types of wood to build a chariot. The Egyptians were the first to use composite bow archers on chariots. Egypt had a significant number of chariots. The chariots also carried shields, axes, and javelins and lances that were attached to the side of the chariots in quivers.

A driver ( Kedjen ) and a fighter ( Seneni ) were used on the car . Contrary to the usual practice in other states, in which only nobles had chariots, in Egypt it was part of the usual army equipment. These chariot fighters, however, formed an elite force within the military, who identified themselves more with chariot fighters from Asian countries than with the other Egyptian soldiers. Most of the time the chariot was manned by archers. The Kedjen protected the Seneni with a large shield made of rawhide against arrows and other projectiles. The Seneni were equipped with heavy textiles for their protection. These retrofits and further developments resulted in a previously unknown speed and mobile combat power on the battlefield.

weapons

The weapon technology of the Hyksos such as chariots, composite bows , an advanced battle ax, helmets and body armor were adopted. However, in all likelihood, bronze scale armor was only worn by elite units such as the chariot divisions.

The preferred melee weapons were dagger and hatchet. The typical armament consisted of preforms of the mace and the sword . The Chepesch sword was well known . The long-range weapons used were spears, slingshots and bows and arrows. Maces were also thrown frequently.

From the 26th dynasty , long spears and lances were introduced, which then became the new main weapon. Many soldiers carried two spears with them, the first being thrown and the second being saved for hand-to-hand combat.

Operation tactics and procedures

Amphibious warfare played a decisive role in the Wars of Liberation. In the course of the war, overtaking landings were made on the Nile, bypassing fortified cities. The fleet was also used in the siege of Auaris . In Nubia, too, the fleet was used to transport troops. The nature of warfare and its potentials changed in the New Kingdom. The prevailing amphibiously oriented warfare shifted to land warfare.

With the reorientation of politics there were serious changes. In addition to the improved weapon technology, there was a sophisticated intelligence system and trained reconnaissance units that were able to clear up the terrain and enemy units in action. Counter-espionage and counter-espionage as well as deception of the opponent about one's own intentions were used to ensure a maximum element of surprise. The results of the reconnaissance and the battle plan were discussed and agreed in a general staff meeting.

The armed forces were deployed by a professionally trained officer corps who could easily lead larger units of various types of weapons and troops. The leadership in battle and the necessary passing on of orders were done by standards, drummers and trumpets as well as by runners, chariots and reports on horses. The standards of the troops enabled the commander on the battlefield to have the necessary overview of the deployment of his units.

In battle

During the war during the advance, fortified marching camps with trenches, enclosing fences and guard posts were built in the enemy territory. On the battlefield the infantry advanced with the chariot detachments on the flanks. Further chariot detachments were held in reserve behind the advancing front. Before the frontal attack of the infantry, the archers mounted on chariots decimated the opposing formations with their far-reaching bows. The use of archers on foot was also conceivable, with simultaneous volleys against opposing infantry to support the chariots. Nubian mercenaries were used as skirmishers in front of the bulk of their own forces. After throwing their spears, they used axes in direct combat with the enemy loosened up by projectiles.

The highly mobile chariot units were used, depending on the situation, to grab the enemy in the flank or to extend a breach into the enemy front. Runner units that were used with the chariots had the task of injuring horses of opposing chariots. A dismounted fight of the chariot crew with axes and javelins was also conceivable. Massive attacks from several hundred closely spaced chariots were possible. They also had a psychological effect on the enemy through the noise and dust they produced. In these cases a direct break-in into the opposing formations was also conceivable.

Reserve chariot squadrons or subsequent infantry units were used to pursue when the enemy fled the battlefield. The experience of amphibious warfare was not lost, however. Thutmose III. led dismantled boats on an advance to the east across the Euphrates with them in order to be able to put his troops across the river.

Fortresses

During the New Kingdom, the existing fortresses of the Middle Kingdom were rebuilt and adapted to new weapon technologies such as chariots and stables for horses. The defensive walls and fortresses built and existing along the western deserts, the Sinai and the Mediterranean coast at this time were intended to prevent a new invasion like that of the Hyksos . The cities were not fortified, but the temple complexes surrounded by high walls could be used as refuges. With the help of fortified watchtowers at strategic points, the movements of strangers were monitored. Lively reconnaissance and reporting activities took place.

mercenary

The Egyptian army was a multilingual army with many ethnic groups, especially in the New Kingdom. The mercenaries were settled in Egypt and were loyal to the Egyptian Empire not only for financial reasons. They never carried out a revolt.

Nubians

Nubian mercenaries have served in the Egyptian army almost continuously since the early dynastic period . They were commonly used as scouts and light infantry since the Second Intermediate Period. The main catchment area in Nubia was Iretjet, Jam , Setiu and Kau, with the Medjia , which had been in use since the 6th Dynasty , were considered to be the best scouts of the entire Egyptian army. Their clothing consisted of leopard and lion skins. Their territory lay on the Upper Nile next to Nubia. During the Middle Kingdom, the Cushites were the greatest threat on the border with Nubia. After the Hyksos were driven out , their territories fell to the New Kingdom. Since then the Kushites have been used as light spear throwers in the Egyptian army.

Other nationalities

Since Amenhotep III. the contingent of soldiers of different nationalities such as Syrians , Libyans , Shardana , Shekelesch , Apiru and even Hittites in the Egyptian armed forces grew . In addition to recruiting as mercenaries, it was quite common to integrate soldiers from conquered areas into the army as prisoners of war.

In the late New Kingdom, mainly Libyans were used as archers. The Libyans wore ostrich feathers in their hair and striking beards. They dyed their hair and skin red. Over time, a significant class developed, the Machimei , and settled in their own villages. Other supporting tribes were the Keukesch , Hes , Schai and Beken . Men from Retenu , Aremu , Charu , Apiru , Shasu or Fenchu were drafted from Syria to strengthen the Egyptian border fortresses and usually provided the contingents with javelins. Some of them were also used on ships, for example. B. under Ramses III. against the sea people . Next Shardana who fought with sword and spear. The Shardana formed their own contingents in the Egyptian army.

In the New Kingdom, the Maryannu were added, who were also brought to Egypt as prisoners of war. They slowly grew up the hierarchy. At the time of Ramses III. they belonged to the officer category. From the middle of the 18th dynasty , the Tehru appear for the first time . From the 20th dynasty they belonged to about the middle of the military hierarchy.

Administration, logistics and medical care

The administrative and logistical organizational structures were at the highest level of development. The state controlled the entire logistics of the army. Ramses II divided the empire into 34 military districts, which were responsible for the recruitment of soldiers, their training and the supply of the army.

administration

For administration and logistics there were clerks for administration and organization at division level. The volume of correspondence was also considerable during the war. Correspondence reached the Pharaoh who was in the field from across the empire, the court and the local administration. Schreiber coordinated the supply and distribution of rations to the infantry and the chariot departments, and they were also responsible for the recruitment, registration of prisoners of war, military prisons and war diaries, as well as reporting.

logistics

The Egyptians maintained repair depots and mobile repair units in order to ensure the functionality of all branches of arms through maintenance and repair. The chariot corps had their own personnel for the selection and training of horses.

The development of the ports of Byblos , Sumur and Arvad in Lebanon and Syria under Thutmose III. mainly served to ensure the logistics and the reception of soldiers transported by sea. The Egyptians used small coastal transporters to ensure the supply of the troops or to transport troops. The Nile remained the main route of transport within Egypt.

Ramses II introduced the ox cart as the basic form of transport. This became the standard mode of transport for the Egyptian army for the next 1000 years. Chariots were also used to transport weapons such as swords, quivers and arrows, javelins and spears. In addition, the soldiers had to carry a considerable amount of food in addition to their equipment and armament. The army on the march was supplied from the country.

medicine

With the beginning of the New Kingdom, the decline of Egyptian medicine began. The lack of military medical service is incomprehensible in an otherwise highly developed military machine, especially in times of military expansion.

The decline

The reasons for the collapse of states are not always clear and mostly a combination of different factors. The military system of a state is closely linked to the political, economic and social development of a country. The available literature gives only sparse information on the subject for ancient Egypt.

The successful defense of the sea peoples by Ramses III. already marked the beginning of Egypt's military decline. Only on its own territory in the western and eastern delta was Egypt able to stop and destroy the invaders. The Third Intermediate Period was marked by a political and military defensive, far removed from the offensive building of an empire at the time of Sesostris III., Thutmose III. or Ramses II. With the end of the New Kingdom (around 1070), the Libyans increasingly infiltrated the delta area. This then led to the Libyan 22nd Dynasty coming to power in 945 . From this point on, Egypt was continuously under foreign rulers. In 818 Egypt split into separate states before the 26th dynasty under Psammetich I and his two successors ( Necho II , Psammetich II ) reunified the country for a short time. This was followed by the invasions and seizures of power by the Cushites , Assyrians , Persians , Macedonians and finally the Romans .

After the end of the New Kingdom, Egypt was no longer economically self-sufficient, especially when it came to strategically relevant raw materials. Iron had to be imported from the Middle East at a time when the influence of the pharaohs in Palestine and Phenicia had rapidly declined. The economic imports and exports were carried out more than usual by Phoenician and Greek merchant ships.

Shipbuilding in Egypt had traditionally not dealt with the construction of ocean-going ships. Although the theory of amphibious warfare was applied and also used for the transport of troops on the Nile, over the sea and on the Euphrates, the concept of sea power , namely as a contribution to the expansion and protection of own trade, was not understood. Rather, its own shipbuilding stagnated, did not show any structural innovations and relied on ship developments from other nations. This created a dangerous dependence on other states. The loss of Nubia also meant the loss of the gold supply, which could hardly be dispensed with both for the state finances and for the temples (gold, the flesh of the gods).

Socially, Egypt developed more and more in the direction of its traditional mythical foundations while at the same time the overemphasis on bureaucracy, which was always latent, increased. This clumsiness of the state, combined with pronounced religious behavior, strengthened the priesthood and contributed to the increasing dominance of the armed forces by foreign mercenaries and immigrants.

See also

literature

- Rolf Gundlach , Carola Vogel : Military history of the pharaonic Egypt. Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2006, ISBN 3-5067-1366-3 .

- Andrea M. Gnirs: Military and Society - A Contribution to the Social History of the New Kingdom. German Archaeological Institute Cairo Department and Egyptological Institute d. University of Heidelberg, Orient, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-9275-5230-5 .

- Robert B. Partridge: Fighting pharaohs - Weapons and Warfare in Ancient Egypt. Peartree, Manchester 2002, ISBN 0-9543-4972-5 .

- Robert G. Morkot: Historical Dictionary of ancient Egyptian Warfare. Scarecrow, Lanham 2003, ISBN 0-8108-4862-7 .

- Simon Anglim, Phyllis G. Jestice, Rob S. Rice, Scott M. Rush, John Serrati: Fighting Techniques of the Ancient World. Amber Books, London 2002.

- Richard A. Gabriel, Karen S. Metz: From Sumer to Rome, the Military Capabilities of Ancient Armies. Greenwood Press, Westport 1991, ISBN 0-313-27645-5 .

- Bridget McDermott: Warfare in Ancient Egypt. Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire 2004, ISBN 0-7509-3291-0 .

- Simon Manley: The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt. Penguin Books, London 1996.

- Anne Millard: Going to War in Ancient Egypt. Franklin Watts, London 2004, ISBN 0-7496-5176-8 .

- Franck Monnier: Les forteresses égyptiennes. Du Prédynastique au Nouvel Empire. Connaissance de l'Égypte ancienne, Safran (éditions), Brussels 2010, ISBN 978-2-87457-033-9 .

- Alan Schulman: army. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 145-147.

- Ian Shaw: Egyptian Warfare and Weapons. Shire Publications, Princes Risborough 1991, ISBN 0-7478-0142-8 .

- Anthony J. Spalinger: Was in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford 2005, ISBN 1-4051-1372-3 .

- Steve Vinson: Egyptian Boats and Ships. Shire Publications, Princes Risborough 1994, ISBN 0-7478-0222-X .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Raulwing: Horse and carriage in ancient Egypt. In: Göttinger Miscellen . (GM) Volume 136, 1993.