Elephantine

| Elephantine in hieroglyphics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

Abu 3bw Elephantine |

|||||||

|

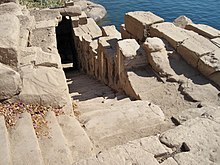

Nilometer as the house of the Nile inundation (end of the stairs, belonging to the Satis temple ) |

|||||||

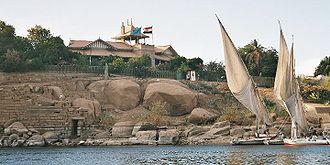

Elephantine (also: Elefantine ; Arabic الفنتين) is a river island in the Nile in Egypt . It extends below the first cataract with a length of 1,200 meters in a southwest-northeast direction and a width of up to 400 meters in a west-east direction between the smaller Kitchener Island and the eastern bank of the Nile. Elephantine is part of the city of Aswan, which is mainly located on the east bank of the Nile .

The ruins of the ancient city of Elephantine have been part of the "Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae" to the UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979 .

geography

Coordinates: 24 ° 5 ' N , 32 ° 53' E

Here on the central reaches of the Nile below the first cataract, the river smoothed its way through a massive granite for the fifth time , creating a granite island with a depression that originally divided the island into two islands for at least a few weeks during the annual Nile flood .

Due to climatic changes between the end of the 4th and the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, The Nile water level and the annual Nile flood height by more than 5 meters. The intensive sedimentation that took place beforehand, as well as artificial landfills and the consistently lower Nile flood heights that followed, combined with the onset of settlement construction, have resulted in no more floods since the Old Kingdom .

Elephantine received the character of an "island grown together" due to the new status due to the climate. On Elephantine there are large deposits of magnificent red-gray rose granite , which was very valuable in ancient times and was reserved for the pharaohs and their buildings. The town of the same name was located on the southeastern end of the island.

Mythology and history

In ancient Egypt as Yebu ( "Elephant") known to Elephantine was on the border between Egypt and Nubia . It formed a natural ship passage point for river trading; its island location made it an important strategic place of defense in ancient times.

As early as the time of the 1st Dynasty , a fortress was built on the eastern side of the island with walls made of mud bricks, and a settlement with the dwellings of the border guards and their families emerged. It soon burst at the seams, and so one of the fortress walls had to be torn down again to make room. Swiss archaeologists, who have their permanent excavation headquarters here, have now found out. The power of the 3rd Dynasty (approx. 2707–2639 BC) was represented by a granite step pyramid ( pyramid of Elephantine ). The first temple was dedicated to the local goddess Satis , the "mistress of Elephantine". It was initially built from adobe bricks. Pepi I (approx. 2355–2285 BC), a king of the 6th dynasty , built a stone shrine for the Satis. The Aries -God Chnum initially received a "Herrgottswinkel" Satis Temple. While Satis was the “trigger of the Nile flood”, Khnum acted as “her helper”.

In the Middle Kingdom era (approx. 2119–1793 BC) the adobe buildings became larger and more regular. They were grouped around central courtyards or formed a so-called three - strip house . During this time, the Satis Temple was initially reinforced with wood, then Pharaoh Mentuhotep II (approx. 2046–1995 BC) had a stone house built, which was built under Sesostris I (1956–1911 BC). was renewed again. He also had the first Khnum temple of his own built on the highest point of Elephantines.

During the New Kingdom , Hatshepsut renewed and enlarged the temple of the Satis. In addition, the worship of the Nubian goddess Miket is documented several times. At the southernmost tip of the island are the ruins of a later temple that was rebuilt in the late period ( 30th Dynasty ). The intensive building activity over the millennia resulted in a considerable settlement mound .

In Persian times a garrison of Jewish soldiers was stationed on Elephantine. They formed their own Jewish community with their own temple. In modern times, part of the hill was removed, water was added to the clay and new building material was formed from it. Part of the history was lost, but today archaeologists can study the historical sequence on the demolition wall. The temple of Thutmose III was located there until 1822 . and Amenhotep III. in a relatively intact condition. In the same year they were destroyed by the Ottomans and looted by the Turkish governors.

Festival calendar from Elephantine

The festival calendar is well documented due to the inscriptions and foundations. The special importance of Elephantine as a source of the Nile flood and a place of rejuvenation was probably the reason for its own festival calendar, which deviated from the general festival calendar of the country:

- 1. Achet I : Amun and Khnum

- 15. Achet II: Amun

- 18. Achet II: Khnum and Anukis

- 28. Achet II: Satis and Anukis

- 9. Achet III: Amun

- 30. Achet III: Anukis

archeology

The new excavation campaigns carried out by Martin Ziermann demonstrate the dramatic drop in the Nile flood heights. While at the time of the 1st dynasty the island fortress still stood on a foundation at around 96 meters above sea level , in the further course the building limit partially decreased to around 91.5 meters. Excavations by the Swiss Institute for Egyptian Building Research and the German Archaeological Institute have uncovered numerous finds that are now on display in the Elephantine Museum. Artifacts from pre-dynastic times have also been found on Elephantine. A small sanctuary of the local saint Heka-ib , who came from the 6th dynasty, dates to the Middle Kingdom. In addition, parts of the city wall from the 1st dynasty and parts of the residential city from all epochs could be exposed.

Compared to the present, in the late fourth millennium BC Chr. Climatic conditions still changed, which enabled Nile floods up to about 99 meters, which is why the settlements had to be rebuilt again and again. Due to the change in the climate, the Nile floods sank to an average of 94.5 meters by the 1st dynasty, and then increased in the further course of the third millennium BC. To level off at about 91 meters. This development went hand in hand with increasing settlement.

The three miles

At first there was only one nilometer in the Satis temple on Elephantine . At the earliest at the beginning of the 26th dynasty , but at the latest under Nectanebo II , the Khnum temple was also subsequently extended by a Nilometer . In the Greco-Roman period , a ritual monumental staircase was finally built , so that from this time on there were three nilometers on Elephantine , which were still in use until the end of the 19th century. The 90 steps down to the river of the Nilometer belonging to the Satis Temple are marked with Arabic , Roman and hieroglyphic numerals, and inscriptions show that the rock was worked in the 17th Dynasty .

The Elephantine Papyri

The elephantine papyri were also discovered by archaeologists on the island. They form a collection of legal documents and letters in Aramaic on papyrus rolls . They prove that various garrisons of Aramaic-speaking ethnic groups were stationed here during the Persian occupation of Egypt, who also followed their own cult here. The documents cover the period from 495–399 BC. In addition to numerous private and business texts (purchase and lease agreements, marriage certificates, inventory lists, tax lists and much more), they also contain an archive copy of a letter to the Persian governor, in which the destruction and looting of the temple in 410 BC . At the instigation of the priesthood of the Khnum Temple and asked for permission to rebuild, instructions for the celebration of individual festivals, but above all contracts and correspondence with the priesthood in Jerusalem and with the governors of Judah and Samaria .

The Jahu Temple and its community

The Elephantine papyri attest to the existence of an Aramaic-speaking Jewish community presided over by a certain Jedanja or Jadanja on the island. The congregation owned a temple of the god Yahu ( YHWH ), which in the texts is always written Yhw or (rarely) Jhh, but never YHWH. This is possibly due to (northern) Israelite tradition - but it can be shown that they must also have known the writing of the tetragram as YHWH. We only know about the time of the foundation of the community that it existed before the Persians under Cambyses II. 525 BC. BC Egypt conquered. The origin of this community can no longer be clearly identified. A part, presumably the Judeans, perhaps migrated after the fall of Judas in 587 BC. A, other Arameans may have already participated in the campaigns of the Assyrian king Asarhaddon 670 BC. Participated against Egypt. The fact that the papyri are written in Aramaic and Achaemenid-Aramaic cursive is due to the multi-ethnic and multi-religious composition of the military colony and its partly international correspondence. Aramaic was international lingua franca .

Despite the close contact to Jerusalem, the reports of the cult at the Temple of Jahu contain few parallels to the Tanakh . Accordingly, the congregation celebrated the Sabbath and Passover , but knew neither the fathers' stories , nor the Exodus and the Torah . No religious literature was found either. Even the existence of a temple for Yhw / YHWH next to Jerusalem after the cult reform of Joschija , which according to 2 Kings 22-23 EU and 2 Chr 34-35 EU already around 620 BC. BC, almost two hundred years before the constitution of the papyri and possibly also before the establishment of the Elephantine community, was astonishing. In addition to Jahu, the texts name other deities, Anat -Jahu, Anat-Bethel and Aschim-Bethel, which are also known from other ancient oriental sources. Research therefore assumes that the Jewish community at the Jahu Temple did not exclusively worship Jhw / JHWH, as later Judaism did , but also integrated other deities. According to Joisten-Pruschke , the most important text that mentions these names in connection with the temple, a tax list of the temple, can also be interpreted in such a way that Anat-Jahu and Aschim-Bethel, unlike Jahu, are not referred to as gods to people employed at the temple. Of course, these forms of personal names cannot be proven elsewhere. The fact that more than 70% of the Hebrew-Aramaic names mentioned in the Elephantine papyri contain a form of the divine name Jahu cannot support this thesis. The papyri also show that syncretistic practices such as the oath of various deities were quite common among the population . According to the repeated complaints of the biblical prophets , the worship of other deities, especially the Anat, was also widespread in the popular religion of Judea.

Everyday life was guided more by the customs of the country than by the prescriptions of the biblical scriptures. The marriage contracts contained in the papyri grant women much more rights than the Old Testament texts do. For example, both spouses had the right to obtain divorce , and a childless woman also had guaranteed property rights in the event of divorce, repudiation and death of the husband.

410 BC The Jahu temple was destroyed. The Judean community, represented by Jedanja, turned three years later to the Persian governor of Judea Bagohi (Bagoas) and the priests at the Jerusalem temple with the request to support the reconstruction. In the letter, Jedanja accused the Khnum priests of having used the temporary absence of the satrap Aršam to bribe the Persian governor (frataraka) Vidranga (Ogdanes). Vidranga is said to have caused the destruction of the Temple of Jahu, which was carried out by Egyptian soldiers under the command of his son, Colonel Nefayan. As Jedanja in 407 BC Chr. Wrote the letter, those involved in the destruction, including Vidranga and Nefayan, were executed. In the letter, Jedanja argues that when Cambyses conquered Egypt (525 BC), all Egyptian temples were destroyed, but the temple of Jahu on Elephantine was spared. In his response, Bagohi advocated reconstruction, with the restriction that only food offering (mincha) and incense incense be carried out. The burnt offering ( ʿola ) of sheep, cattle and goats was forbidden, which is possibly due to the fact that the burning of an animal did not agree with the concept of the Persian state religion Zoroastrianism of the purity of the sacred fire, or the sacrifice of the Egyptians sacred animals had led to hostilities with the Khnum priests. Only a few years later, Persian rule over Egypt ended. With that all news about the Judean community on Elephantine will also disappear.

Sights, tourism and population

In addition to the archaeological site, the Aswan Museum , a luxury hotel owned by Mövenpick Holding and two villages with Nubian residents are now on the island .

literature

(sorted chronologically)

overview

- Labib Habachi : Elephantine. In: Wolfgang Helck (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Ägyptologie (LÄ). Volume I, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1975, ISBN 3-447-01670-1 , Sp. 1217-1225.

- Werner Kaiser : Elephantine. In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 283-89.

- Gabriele Höber-Kamel (ed.): Elephantine, the gateway to Africa (= Kemet issue 3/2005 ). Kemet Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISSN 0943-5972 .

Monographs

- Horst Jaritz: Elephantine III. The terraces in front of the temples of Khnum and Satet. (= Archaeological Publications. (AV) Vol. 32). von Zabern, Mainz 1980

- Günter Dreyer : Elephantine VIII. The Temple of Satet. Part 1: The finds from the early days and the Old Kingdom. (= Archaeological Publications. Vol. 39). von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-8053-0501-X .

- Martin Ziermann : Elephantine XVI. Fortifications and urban development in the early days and in the early Old Kingdom (= Archaeological Publications. Vol. 87). von Zabern, Mainz 1993.

- Cornelius von Pilgrim: Elephantine XVIII. Investigation in the city of the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period. (= Archaeological Publications. Vol. 91). von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1746-8 .

- Hanna Jenni: Elephantine XVII. The decoration of the temple of Khnum on Elephantine by Nektanebos II (= Archaeological Publications. Vol. 90). von Zabern, Mainz 1998, ISBN 978-3-8053-1984-3 .

- Martin Ziermann: Elephantine XXVIII. The building structures of the older city (early period and old empire), excavations in the northeast city (11th – 16th campaign) 1982–1986. von Zabern, Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-8053-2973-3 .

- Mieczyslaw D. Rodziewcz, Elzbieta Rawska-Rodziewicz: Elephantine XXVII. Early Roman Industries on Elephantine (= Archaeological Publications. Vol. 107). von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3266-1 .

Questions of detail

- Walter Honroth, Otto Rubensohn , Friedrich Zucker : Report on the excavations on Elephantine in the years 1906–1908 . In: Georg Steindorff (Hrsg.): Journal for Egyptian language and antiquity . Volume 46 (1909-10). Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1909, p. 14–61 ( archive.org [accessed April 12, 2016]).

- Stephan Seidlmayer : Historic and modern Nile stands. Investigations into the level readings of the Nile from the early days to the present. Achet, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-9803730-8-8 .

- Martin Bommas: The temple of Khnum of the 18th Dyn. On Elephantine. Diss., Heidelberg 2003. Download (PDF; 15.6 MB).

- Anke Joisten-Pruschke : The religious life of the Jews of Elephantine in the Achaemenid period. (= Göttingen Orient Research III. Iranica series ). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-447-05706-6 .

Web links

- Cataloging of the Elephantine papyri in the National Museums in Berlin - Rubensohn Collection

- Angela Rohrmoser: Elephantine. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on May 26, 2012.

- Martin Bommas: The Temple of Khnum of the 18th Dyn. On Elephantine, Heidelberg 2003 (PDF; 15.6 MB)

- Plan of Elephantine / map with German lettering

- Martin Ziermann: Building structure in the early days and in the Old Kingdom . (PDF)

- Elephantine . Swiss Institute for Egyptian Building Research and Archeology (Cairo)

- Exhibition “Jewish Life in Ancient Egypt”, 2004. Brooklyn Museum

Individual evidence

- ^ Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae. whc.unesco.org, accessed April 26, 2015 (ID 88-007: Ruins of town of Elephantine ).

- ↑ Stephan Seidlmayer: Historic and modern Nile stands . Pp. 81-82.

- ^ Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Munich 1997, p. 108.

- ↑ Anke Joisten-Pruschke: The religious life of the Jews of Elephantine in the Achaemenid period (= Göttinger Orientforschungen. Vol. III; series: Iranica ). Wiesbaden 2008, p. 68.

- ↑ Michael Weigl: The Aramaic Achikar sayings from Elephantine and the Old Testament wisdom literature . de Gruyter, Berlin 2010, ISBN 3-11-021208-0 , pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Jörn Kiefer: The Jewish community of Elephantine. Life in the Diaspora during the Persian period. In: World and Environment of the Bible No. 3, 2011, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Anke Joisten-Pruschke: The religious life of the Jews of Elephantine in the Achaemenid period p. 94.

- ^ Michael H. Silvermann: Religious Values in the Jewish Proper Names at Elephantine. In: Old Orient and Old Testament. (AOAT) No. 217, 1985, pp. 216, 233.

- ↑ Anke Joisten-Pruschke: The religious life of the Jews of Elephantine in the Achaemenid period. Pp. 113-121.

- ↑ a b Jan Assmann : Moses the Egyptian . Deciphering a memory trace. 7th edition. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-596-14371-9 , The victim of the Passover lamb, p. 95/96 .

- ↑ Anke Joisten-Pruschke: The religious life of the Jews of Elephantine in the Achaemenid period. P. 71.